Home | Category: New Kingdom (King Tut, Ramses, Hatshepsut) / Ancient Hebrews and Events During Their Time / Ancient Hebrews and Events During Their Time

PHILISTINE-SEA-PEOPLE ARCHAEOLOGY

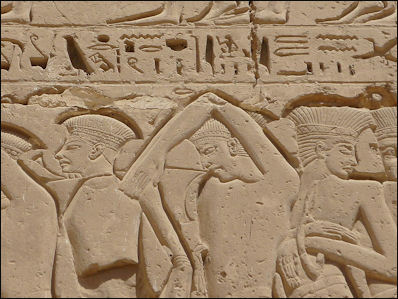

Philistine captives depicted in the

Ancient Egyptian temple of Medinet Habu ISome scholars believe the Philistines and Sea People are one in the same or at least overlap to some degree; even so it is unclear where they originate from. Since the 1990s, archaeologists have extensively excavated four of the five cities of the Philistine Pentapolis: Ashdod, Ashkelon, Ekron, and Gath. The only that hasn’t is in Gaza and is located beneath the modern Palestinian city of Gaza. Excavations under the direction of Aren Maeir at the Israeli site of Tell es-Safi have revealed the ruins of the city of Gath, which was occupied by the Philistines during most of the Iron Age (ca. 1200 — 539 B.C.)

Ilan Ben Zion wrote in Archaeology Magazine: In the heat of the day, a glint off the Mediterranean is just visible from the top of a mound known as Tell es-Safi that rises some 300 feet above Israel’s coastal plain. For generations, scholars believed that the stretch of Mediterranean coast west of Tell es-Safi was once the landing point of multiple invasions of Philistines or Sea People [Source: Ilan Ben Zion, Archaeology Magazine, July-August 2022]

The ruins of Gath, a Canaanite center that became the Philistines’ mightiest city, now lie beneath Tell es-Safi, which means “white hill” in Arabic. The mound’s white chalk cliffs, which overlook fertile farmland, inspired the Crusaders to name the castle they built there in the twelfth century A.D. Blanche Garde or White Fortress. Until the war that followed Israel’s founding in 1948, the tell was home to a small Palestinian village whose ruins are now overgrown with thorns.

In the past quarter century,Maeir and his team have opened more than 100 excavation squares at Tell es-Safi, each measuring 16 by 16 feet. In the process, they have unearthed monumental fortifications including a massive gate, as well as metalworking facilities and a Late Iron Age temple, all of which demonstrate Gath’s importance in the southern Levant during the Philistine era. The team has found that in the centuries following the Philistines’ arrival, Gath grew and, at its peak in the ninth century B.C., was home to an estimated 10,000 inhabitants. Jerusalem, by comparison, would not reach that size until the eve of its destruction in 586 B.C. Gath’s location straddling trade routes that connected inland copper mines with the coast likely contributed to its status as the most important member of the Philistine Pentapolis and made it one of the most significant city-states in the southern Levant.

RELATED ARTICLES: SEA PEOPLES africame.factsanddetails.com ; ; HISTORICAL PHILISTINES: RECORD OF THEM AND WHERE THEY LIVED africame.factsanddetails.com ; BIBLICAL PHILISTINES: GOLIATH, SAMSON AND DELILAH— AND UNDESERVED BAD RAP? africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Virtual Jewish Library jewishvirtuallibrary.org/index ; Judaism101 jewfaq.org ; torah.org torah.org ; Chabad,org chabad.org/library/bible ; Yivo Institute of Jewish Research yivoinstitute.org ; Bible and Biblical History: ; Biblical Archaeology Society biblicalarchaeology.org ; Bible History Online bible-history.com Bible Gateway and the New International Version (NIV) of The Bible biblegateway.com ; King James Version of the Bible gutenberg.org/ebooks ; Jewish History: Jewish History Timeline jewishhistory.org.il/history Jewish History Resource Center dinur.org ; Center for Jewish History cjh.org ; Jewish History.org jewishhistory.org ; Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Sea Peoples of the Bronze Age Mediterranean c.1400 BC–1000 BC (Elite)” by Raffaele D’Amato , Andrea Salimbeti, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Sea Peoples: Warriors of the Ancient Mediterranean 1250-1150 BC” by N. K. Sandars Amazon.com ;

“People of the Sea: The Search for the Philistines” by Trude Dothan and Moshe Dothan Amazon.com ;

“The Philistines and Other Sea Peoples in Text and Archaeology” by Ann E. Killebrew and Gunnar Lehmann Amazon.com ;

“The Philistines and the Old Testament” by Edward E. Hindson Amazon.com ;

“The Philistines and Aegean Migration at the End of the Late Bronze Age”

by Assaf Yasur-Landau Amazon.com ;

“Why the Bible Began: An Alternative History of Scripture and its Origins” by Jacob L. Wright Amazon.com ;

“The Bible Unearthed” by I. Finkelstein and N. Asher Silberman Amazon.com ;

“Archaeology of the Bible: The Greatest Discoveries From Genesis to the Roman Era”

by Jean-Pierre Isbouts Amazon.com ;

“Zondervan Handbook of Biblical Archaeology: A Book by Book Guide to Archaeological Discoveries Related to the Bible” by J. Randall Price and H. Wayne House Amazon.com ;

“NIV, Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible (Context Changes Everything) by Zondervan, Craig S. Keener Amazon.com ;

“Egypt, Canaan and Israel in Ancient Times” by Donald Redford Amazon.com ;

“Oxford Companion to the Bible” by Bruce M. Metzger and Michael David Coogan Amazon.com ;

“The Bible as History” by Werner Keller Amazon.com ;

“Historical Atlas of the Holy Lands” by K. Farrington Amazon.com

Philistines First Thought to Be Mycenaeans

Ilan Ben Zion wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Finds from limited excavations during the early twentieth century pointed archaeologists to the Aegean as the Philistines’ original homeland. The conquerors, they imagined, were Mycenaeans, members of the Late Bronze Age culture of ancient Greece remembered in the epic poems of the Trojan War, Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. [Source: Ilan Ben Zion, Archaeology Magazine, July-August 2022]

Early twentieth-century archaeologists made a number of discoveries that seemed to reinforce biblical and Egyptian descriptions of the Philistines. Excavations at Ashkelon and Beth Shemesh — an Israelite city east of Gath mentioned in the Book of Judges as the location to which the Philistines returned the stolen Ark of the Covenant — unearthed early Philistine ceramics that closely resemble types of Mycenaean pottery found throughout the Aegean.

These early Philistine wares feature geometric patterns in red and black and are sometimes decorated with depictions of birds’ heads akin to those in the Medinet Habu reliefs. The Mycenaeans are known to have used these vessels for drinking and feasting, and the Philistines likely used them in the same way. Although these ceramic vessels provided the first firm connection between the Philistines and the Aegean world, later examinations of other pieces of early Philistine pottery revealed that they were crafted from local Canaanite clay. From the beginning, then, Philistines were adapting their culture to local conditions.

Evidence That the Philistines Came from Crete

Samson Kills 1,000 Philistines Ilan Ben Zion wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Wheaton College archaeologist Daniel Master, who codirected recent excavations at Ashkelon, the Philistine port 18 miles west of Tell es-Safi, believes that the Philistines likely hailed from Crete and conquered Canaanite cities during a brief window around 1175 B.C. Philistine pottery resembling ceramics from Mycenaean sites was a product of a single stylistic moment, Master says. Those pottery types and decorative styles, he thinks, changed in parallel in Philistia and the Aegean during a single generation. [Source: Ilan Ben Zion, Archaeology Magazine, July-August 2022]

DNA analysis of some remains from the cemetery showed the deceased individuals likely came from Crete.The 2013 discovery of a cemetery at Ashkelon, the first large burial ground to be excavated at one of the cities of the Philistine Pentapolis, has helped bolster Master’s view. This cemetery contained some 200 burials dating to the Philistine period in which individuals were interred separately. This is unlike Canaanite funerary practices in which the dead were cremated or buried collectively in pits or tombs.

Genetic analysis of these remains, says Master, supports Egyptian accounts of the Philistines’ origins. He was part of a team that analyzed the DNA of 10 individuals found in the Ashkelon cemetery: three dating from the Bronze Age, four from the Early Iron Age, and three dating to the tenth to ninth century B.C. The team found that DNA sampled from the Early Iron Age burials had a European genetic component that set the people apart from the local Bronze Age Canaanite population and supports the idea that the Philistines originated in Crete.

Recent Discoveries Shed Light On the Complexity of Philistine Origins

More recent excavations at Philistine sites have revealed more insights into the complexity of the origins of the Philistines and the development of their culture. Ilan Ben Zion wrote in Archaeology Magazine: These digs, particularly the long-term excavations of the ruins of Gath beneath Tell es-Safi, have helped archaeologists tell a more nuanced story about the origins of the Philistines, which may lie in a series of mass migrations rather than waves of conquest. “Understanding the Philistines as this singular, unified migratory group that came from somewhere in Greece, landed on the coast, and conquered the Canaanite cities no longer makes sense,” says Bar-Ilan University archaeologist Aren Maeir, who directs the Tell es-Safi excavations.

Maeir and many of his colleagues suggest that the Philistines were an eclectic and multiethnic group of migrants, not a uniform horde of invaders. He believes it’s likely they hailed from various locations around the eastern Mediterranean and moved to the Levant over many decades between the late thirteenth and mid-twelfth centuries B.C. They settled, mostly peaceably, among the local Canaanites, creating a distinct hybrid culture that endured for much of the Iron Age. “What we’ve learned about Philistine culture at Gath,” Maeir says, “is that the process of its origins, formation, transformation, and development is much more complex than was originally thought.”

All demonstrate Gath’s importance in the southern Levant during the Philistine era. The team has found that in the centuries following the Philistines’ arrival, Gath grew and, at its peak in the ninth century B.C., was home to an estimated 10,000 inhabitants. Jerusalem, by comparison, would not reach that size until the eve of its destruction in 586 B.C. Gath’s location straddling trade routes that connected inland copper mines with the coast likely contributed to its status as the most important member of the Philistine Pentapolis and made it one of the most significant city-states in the southern Levant. [Source: Ilan Ben Zion, Archaeology Magazine, July-August 2022]

Other discoveries have helped Maeir and his team develop a more nuanced take on Philistine culture. Among their most important finds is a ninth-century B.C. two-horned altar, which combines decorative elements from the Levant with those known from Cyprus and the Aegean. It is the oldest such altar in Philistia. The team also found a sherd bearing inscriptions written in Canaanite script with two names that are close to Goliath, suggesting that the now-famous name may have been common in Philistia. At the same time, they have discovered copious amounts of Canaanite pottery and other artifacts dating to the earliest stages of the Philistine period. The picture of Philistine Gath emerging from recent excavations, says Maeir, is one of a vibrant metropolis where migrants from around the Mediterranean lived cheek-by-jowl with Canaanites. For several generations, these two distinct cultures coexisted before combining into one.

Multi-Cultural Philistines

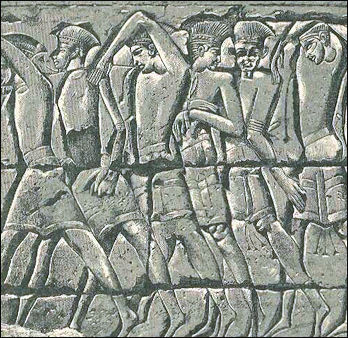

Philistine prisoners in Egypt Ilan Ben Zion wrote in Archaeology Magazine: University of Melbourne archaeologist Louise Hitchcock, who directed excavations in a residential district at Tell es-Safi, remains cautious about the Ashkelon DNA findings. She points to the study’s small sample size. “I don’t think you can say they were Philistine based on their DNA,” Hitchcock says, “but you can based on their full realm of material culture.” In recent years, finds from Gath, Ekron, and Ashkelon have all suggested that Philistine culture was eclectic and had parallels in Late Bronze Age cultures from throughout the eastern Mediterranean. Researchers have analyzed dog bones from Philistine sites that suggest that, like pigs, dogs were part of the Philistine diet, as they were across the Aegean and Anatolia. Nonlocal flora from around the Mediterranean, including sycamore, poppy, and cumin, first appeared in the Levant at Philistine sites. [Source: Ilan Ben Zion, Archaeology Magazine, July-August 2022]

Some finds, such as circular pebbled hearths similar to those found in the center of homes in Greece and Cyprus, cult objects such as figurines of goddesses with their arms raised in a shape resembling the Greek letter psi (Ψ), and Cypriot-style notched cow scapulas possibly used in soothsaying, underscore that the Philistines were connected to the ancient Greek world. At the same time, a seated female figurine discovered at Ashdod featuring an unusual combination of Aegean and Levantine styles demonstrates the rich combination of cultural influences that permeated the world of the Philistines.

Early Philistine culture does not feature the hallmarks of one particular place of origin — a single cultural package of ritual objects, ceramic styles, and social customs, Maeir says. “Rather, we seem to have a little bit from Greece, and a little bit from Cyprus, and a little bit from Crete, and from Anatolia and other places.” At the same time, Canaanite cultural practices that predate the Philistines, such as placing an oil lamp within a bowl and burying it beneath the floor of a building as a kind of offering, continued uninterrupted after their arrival.

Philistines: The Result of a Merging of Migrations?

Ilan Ben Zion wrote in Archaeology Magazine: Hitchcock says the archaeological record doesn’t neatly match the traditional scholarly accounts of Philistine invasion and colonization. In particular, she points to the absence of evidence of violent conquest at Philistine sites, including Gath. “We go straight from early Philistine layers down into Late Bronze Age layers with no evidence of destruction,” she says. “This calls into question the whole myth of the Philistines as an invading force of Mycenaean colonizers sweeping in and taking over.” In addition, very few weapons have been found at Philistine sites, an absence that challenges the martial image of the Philistines presented in the Bible. [Source: Ilan Ben Zion, Archaeology Magazine, July-August 2022]

Maeir and Hitchcock propose that the people who became the Philistines were part of migrating populations who formed opportunistic pirate tribes. These groups may have roamed the Mediterranean, taking on followers from a number of different disrupted societies. “When Egypt loosened its grip on Philistia, these groups finally settled in among the local population,” Hitchcock says. The scholars believe that some of the peoples who comprised the Philistines were multiethnic groups of raiders possibly analogous to Atlantic pirates of the seventeenth century A.D., who are known to have come from many different nations.

These Late Bronze Age pirates may have spoken different languages and chosen particular symbols that bound them together as a group in the way many early modern pirates rallied to the Jolly Roger. The Aegean-style drinking and feasting ware found at Philistine sites, Maeir and Hitchcock suggest, may have served as just such a symbol. They point out that feasting was an important feature of Bronze Age society and played a central role in the culture of more recent pirates as well. It’s also possible that the feathered and horned helmets and the birds’ head prows depicted on the Medinet Habu reliefs served as potent symbols that a diverse group of pirates could rally around. The scholars further suggest that seren, the word describing the leaders of the Peleset chiefs on the Medinet Habu reliefs, may not come from the Greek word tyrannos after all. Instead, they believe it may be related to the word tarwanis used by the Luwian people of southern Anatolia to describe warlords. Perhaps it was these Bronze Age Blackbeards who became the first Philistines.

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024