Home | Category: Judaism Beliefs / Judaism, Jews, God and Religion

GOD AND JUDAISM

Kabbalistic creator Jews believe that: 1) God is creator and absolute ruler of the universe, and there is only one all powerful god. 2) Man has free will, he is not inherently sinful, and he has the ability to choose between good and evil, and even choose to rebel against God. 3) The Jewish people have a special relationship with God because he revealed the “Torah” to them at Mt. Sinai. By obeying God's law they will be a special witness of God's mercy. 4) God knows the deeds and thoughts of people.

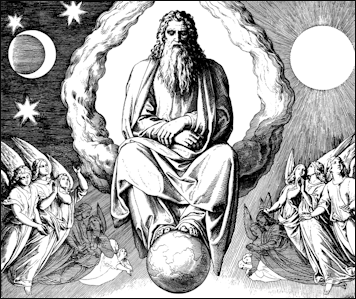

Judaism is a monotheistic faith affirming that God is one, the creator of the world and everything in it. The unity of God and the obligation to worship him alone are core beliefs in monotheism. The incorporeality and eternity of God are reference to undescribable and unfathomable aspects of God and his existence beyond time and space. Inherent in the belief of God’s Omniscience is a belief that God knows everything including our innermost thoughts and righteousness is not necessarily based on displays and actions.

According to Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: God is also a transcendent being above and beyond the world and is thus without material form, and yet he is present in the world. His will and presence are especially, but not exclusively, manifest in his relationship with Israel (the Jewish people), to whom he has given the Torah (teaching), stipulating the laws that are to govern their religious and moral life, by virtue of which they are to be "a light unto the nations" (Isa. 49:6). Accordingly, Jews understand themselves as a chosen people, bound by a covenant with God. [Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

In Judaism faith is less a matter of affirming a set of beliefs than of trust in God and fidelity to his law. Faith is thus primarily expressed "by walking in all the ways of God" (Deut. 11:22). These ways are specified in God's revealed law, which the rabbis, or teachers, appropriately called the Halakhah (walking). The commandments of the Halakhah embrace virtually every aspect of life, from worship to the most mundane aspects of daily existence. Geoffrey Parrinder wrote in “World Religions”, "The dilemma of the Hebrew is not the question whether God exists, or why he exists, but rather how he acts in the world, and what he requires of people. The natural world is a manifestation of God's glory...The God of the Bible is both a remote transcendent being, imposing his awe upon the universe, demanding absolute obedience...and also a loving and compassionate father, who has a close personal relationship with those who revere him." [“World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder, Facts on File Publications, New York]

Websites and Resources: Bible and Biblical History: Bible Gateway and the New International Version (NIV) of The Bible biblegateway.com ; King James Version of the Bible gutenberg.org/ebooks ; Bible History Online bible-history.com ; Biblical Archaeology Society biblicalarchaeology.org ; Judaism Virtual Jewish Library jewishvirtuallibrary.org/index ; Judaism101 jewfaq.org ; torah.org torah.org ; Chabad,org chabad.org/library/bible ; BBC - Religion: Judaism bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/judaism ; Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu

Terms and Descriptions of the Jewish God

The source of our information about God is the Old Testament, which is largely ascribed to Moses. In the early passages of the Old Testament, God is referred to by several names including El Shaddai, which some scholars say signifies a storm god or god of power, and El 'Elyon. In Exodus 3:14 he reveals his true name to be Yahweh (YHVH, Jehovah). El Shaddai means "God of the Mountain." El 'Elyon means "God Most High." In classical texts God was regarded as unknowable: “Thou can not See My Face.” Until the Kabbalists came along Jews accepted that description and did not dwell much on the matter.

Jews use the name God. Common names for God found in the Hebrew Bible include Yahweh and Elohim. In the West, the Jewish God is known as Jehovah. Jehovah is English for the Hebrew word Yahweh, which is more properly known as YHWH. The pronunciation of YHWH has been lost. It word is believed to mean "he who causes things to be" and in Biblical times was so holy that no one was allowed to say it except for the highest-level priests in important ceremonies.

The Jews did not attempt to pronounce YHWH. It was too holy. Instead they said “HaShem” , the “name.” The famous rabbi Haninina ben Teradion was reportedly tortured to death for uttering the "unutterable." The use of the word Lord to describe God came into usage in part so believers didn’t have to use the word God. The name Jehovah, coined in the Middle Ages, was not used in the Hebrew Bible.

God Early in the Torah and the Bible

At the beginning of the Hebrew Bible, after the Creation, God resembles a local pagan deity. The poet Stephen Mitchell described him as a "jealous, bungling, punitive god, not the god we can love with all our hearts and soul." In the Old Testament, God often displayed extreme bouts of anger whenever humanity disappointed him, especially by sinning with sex. In addition to wiping out entire nations of sinners, God also killed a lot of animals who had done nothing wrong. Many scenes involving God's anger have been edited out of the children's versions of the stories.

At the beginning of the Hebrew Bible, after the Creation, God resembles a local pagan deity. The poet Stephen Mitchell described him as a "jealous, bungling, punitive god, not the god we can love with all our hearts and soul." In the Old Testament, God often displayed extreme bouts of anger whenever humanity disappointed him, especially by sinning with sex. In addition to wiping out entire nations of sinners, God also killed a lot of animals who had done nothing wrong. Many scenes involving God's anger have been edited out of the children's versions of the stories.

In his unorthodox introduction to the Bible, the bestselling British author Louis de Bernieres wrote: "There are many episodes in the Bible that show God in a very bad light...and one cannot but conclude from them either that God is a mad, bloodthirsty and capricious despot, or that all this time we have inadvertently worshipped the Devil."

Much of God’s anger is directed at people who continue to worship other Gods. After God sees the Israelites with the golden calf which they began worshipping while Moses was on Mt. Sinai, God says: "Now let me be, that my anger may blaze forth against them and I may destroy them, and make you a great nation."

Over the course of the early Bible, God changes from a being that urges his followers to dash the heads of their enemies’ babies on rocks to the god in Isaiah that tells them to love their enemies. In the beginning of the Old Testament, God is quite busy and present. He shows up at the Garden of Eden, speaks to Abraham and Moses and even wrestles around with Jacob. As the Bible progresses he appears and speaks less and less until he virtually disappears.

Jewish Beliefs About God

Jews believe that there is a single God who not only created the universe, but with whom every Jew can have an individual and personal relationship. They believe that God continues to work in the world, affecting everything that people do. The Jewish relationship with God is a covenant relationship. In exchange for the many good deeds that God has done and continues to do for the Jewish People. The Jews keep God's laws. The Jews seek to bring holiness into every aspect of their lives. [Source: BBC |::|]

Some Jewish beliefs about God: 1) God exists. Jews rarely offer any proof that God exists. The first line of the first book of the Torah, Genesis, states, "In the beginning, God created heaven and Earth." God, therefore, existed before the universe did, and he created everything in it, including evil. 2) There is only one God; Unlike some religions, which believe in the concept of a god that manifests, or appears, in various ways or through various figures or minor gods, Jews believe that God is a single entity that cannot be described by his attributes. He exists everywhere, is all powerful, and all knowing ("omniscient"). 3) God is incorporeal. This means that God does not have a body or any physical attributes, including gender. God is a "he" primarily because Hebrew, the ancient language of the Jewish people, does not have neuter words, that is, words whose grammatical gender is neither masculine nor feminine. 4) God is eternal. He has no beginning and no end and is beyond time. [Source: Encyclopedia.com].

Jews also believe: 1) God can't be subdivided into different persons (unlike the Christian view of God); 2) Jews should worship only the one God; 3) God is Transcendent: God is above and beyond all earthly things; 4) God is omnipresent; 4) God is everywhere, all the time; 5) God is omnipotent; 6) God can do anything;; 7) God has always existed and will always exist; 8) God is just, but God is also merciful; 9) God punishes the bad and rewards the good; 10) God is forgiving towards those who make mistakes; 11) God is personal and accessible; 12) God is interested in each individual; 13) God listens to each individual; 14) God sometimes speaks to individuals, but in unexpected ways. |::|

According to the BBC: “The Jews brought new ideas about God. The Jewish idea of God is particularly important to the world because it was the Jews who developed two new ideas about God: 1)There is only one God; and 2) God chooses to behave in a way that is both just and fair. Before Judaism, people believed in lots of gods, and those gods behaved no better than human beings with supernatural powers. The Jews found themselves with a God who was ethical and good. |::|

“Jews combine two different sounding ideas of God in their beliefs: 1) God is an all-powerful being who is quite beyond human ability to understand or imagine. 2) God is right here with us, caring about each individual as a parent does their child. A great deal of Jewish study deals with the creative power of two apparently incompatible ideas of God.” |::|

Monotheism in Judaism

Judaism is a monotheistic (one god religion). According to high Jewish doctrine, Jews are in the world to be witnesses to the claim that there is one God with whom humans can have contact: God has chosen them to act as messengers, whose task it is to pass on these details to the rest of the world.

Judaism is a monotheistic (one god religion). According to high Jewish doctrine, Jews are in the world to be witnesses to the claim that there is one God with whom humans can have contact: God has chosen them to act as messengers, whose task it is to pass on these details to the rest of the world.

According to the BBC: 1) Monotheism: A) Exclusive monotheism: Denial of other gods. B) Diaspora Jews had more tolerant tradition. 2) Creation and its implications: A) Sabbath; B) God s control of individuals and history, including tragedies. 3) Attitudes towards dualism Range of approaches: A) Dualism: Role of Satan; B) Children of Light vs. Children of Darkness (ruled by Angel of darkness ); c) Evil comes from God. 4) Determinism: Differences among three parties. Implication with respect to accountability (reward and punishment) . [Source: BBC]

Israelite monotheism is interesting in that God was seen as universal but that the demand to worship was not. Only the Jews were expected to serve him. They believed God takes a special interest in mankind and demands that they listen and obey him in a way that serves god’s interest. In turn God selected a small group of people in Ur then in Egypt to form a covenant with. In some passages Israel is described as God’s spouse.

God is viewed by Kabbalists as having different aspects but ultimately is regarded as one. Angels sometimes appear in the liturgy as messengers to God but ths view is controversial.

God and the Scriptures

But how do Jews know this about God? According to the BBC: “They don't know it, they believe it, which is different. However, many religious people often talk about God in a way that sounds as if they know about God in the same way that they know what they had for breakfast. For instance, religious people often say they are quite certain about God - by which they mean that they have an inner certainty. And many people have experiences that they believe were times when they were in touch with The best evidence for what God is like comes from what the Bible says, and from particular individuals' experiences of God. [Source: BBC |::|]

“Quite early in his relationship with the Jews, God makes it clear that he will not let them encounter his real likeness in the way that they encounter each other. The result is that the Jews have work out what God is like from what he says and what he does. The story is in Exodus 33 and follows the story of the 10 commandments, and the Golden Calf. |::|

“Moses has spent much time talking with God, and the two of them are clearly quite close. The Lord would speak to Moses face to face, as a man speaks with his friend. But after getting the 10 commandments Moses wants to see God, so that he can know what he is really like. God says no...you cannot see my face, for no one may see me and live. Then the LORD said, There is a place near me where you may stand on a rock. When my glory passes by, I will put you in a cleft in the rock and cover you with my hand until I have passed by. Then I will remove my hand and you will see my back; but my face must not be seen.” |::|

Some people regard Judaism as a strict religion that emphasizes a "God of wrath." They believe that Judaism emphasizes the "justice" of God at the expense of mercy. Many Jews take issue with this belief, pointing out that of the two names used most frequently in the Hebrew Bible to refer to God, the name that refers to His mercy is used just as often as the other.

Atheist Christopher Hitchens and Rabbi Debate the Existence of God

YHWH (circled) in Lakish Letters

David Wolpe is the rabbi of Sinai Temple in Los Angeles and the author of "Why Faith Matters." He engaged in several public debates on the existence of God with Christopher Hitchens, a well-known journalist and critic, professed atheist and author the best-selling "God Is Not Great". Hitchens, who was stunned to discover in his 30s that he was Jewish and had a Passover seder at his house ever year, died in 2011 of cancer.

Describing an exchange with Hitchens, Wolpe wrote in the Washington Post: “As we climbed the podium, I mentioned that his book title, "God Is Not Great," (which, on the book's cover, has a pugnaciously lowercase "god") was exactly correct. Maimonides said in the 12th century that any affirmative statement about God must be incorrect because it's inherently limiting. You can say "God is not bad," and that leaves an infinite number of things for God to be. But, strictly speaking, to say "God is great" might be taken to mean not very great, or not transcendent. So you see, I told him, we agree. "Good," he answered. "Why don't we begin with that?" [Source: By David Wolpe, Washington Post, July 4, 2010 +++]

“I wasn't so naive as to begin a debate in front of 2,000 people by acceding to my opponent's book title, but having viewed his previous performances, I was prepared to hit a few tender spots. When he maintained that religion is stupid because it presumes that humans possessed no morality until God told them what to do, I answered that the Bible condemns Cain's murder of Abel long before any laws were handed down at Sinai. The Bible knows that we know murder is wrong. The function of the "Thou shall not kill" commandment, I said, is to reinforce that the prohibition is not simply a societal rule but a mandate from God to all people. "And if you think that mandate doesn't matter," I concluded, "all I can say is you haven't paid much attention to the 20th century." +++

“I felt good about that exchange — the way boxers, staggering up from the canvas, think back to that one jab they landed. We then sparred over some old terrain: I insisted that if we are products of evolution and genetics alone then we have no certain ground for morality. For if morals do not originate beyond ourselves, why not disobey whenever we feel it will benefit us? He countered that morality was a strange plea coming from religion, a source of so much suffering. I said Nazism and communism (secular ideologies both) speak poorly for societies without religion. He countered with religion's oppression of women. And besides, he said, isn't circumcision really mutilation, if we're honest about it? +++

“When Hitchens told the audience that night that religion is "a wish to be loved more than you probably deserve," I countered that such a theme is always adopted by those deriding religion: I am a nonbeliever because I am reasonable, they say, and you are a believer because you need a crutch. Beware, I told the group, of people who explain their own beliefs by reason and others' beliefs by psychology. Hitchens insisted he was being accurate, not comprehensive; there are many other reasons to distrust religion apart from its spurious comfort. When a person does something good in religion's name, Hitchens dismisses religion as the cause, but when people do evil, it is religion's fault. I reply that people don't need religion to make them do bad things. Rather, they need religion to lift them above the bad things they would otherwise instinctively do. +++

Christopher Hitchens

“What I cannot counter is Hitchens's experience of reporting in virtually every war-torn region in the world, and in places where religion has too often taken a benighted stand against medicine. And he has a delicious store of foolish religious teachings at his fingertips: "Thomas Aquinas believed himself capable of levitating," he says, and apparently took a tour of Notre Dame — from above. +++

“Despite our shtick, there are real principles at stake each time. That is Hitchens's gift: a dance between mockery and erudition. In his world, God is a fabrication and a cudgel. In mine, God is a solace and a guide. I was reminded of this distinction when I heard the sad news last week that Hitchens is about to undergo treatment for cancer. I have no doubt that he will face it with the same stoic courage with which he has met other challenges. There is no reason to suppose it will change his convictions; I have undergone neurosurgery and chemotherapy with my faith unshaken — why assume he could not emerge with his unbelief unchanged as well?... In the meantime, on we battle; Hitchens challenges me with how much evil happens in a good God's world. I talk about religion's contributions, its spur to altruism, and point to the mystery of consciousness and the wide testimony of religious experience. I claim that he has no warrant for free will if everything is a product of genetics and environment. He compares God to the dictator of North Korea — except with a dictator, "at least you are released from his grip at death." Later we sign copies of our books for the audience. Five or 10 kindly souls stand in my line. His stretches out as long as the eye can see. He looks up at me and winks. The smart money, he seems to be saying, is in heresy.”

Archaeologists Find an Early Portrait of Yahweh (God)?

In 2020, archaeologists said they found what was perhaps an early portrait of god. Candida Moss, wrote in the Daily Beast: Excavations in the ancient Kingdom of Judah, close to Jerusalem in Israel, have unearthed a number of anthropomorphic male figurine heads from the 10th century B.C. A bearded man with a square flat-topped head, protruding nose, holes for earrings, and somewhat bulging eyes. The similarity between the figurine heads suggests that they depict the same figure, but who is this oddly shaped character? In an article published in July 2020, archaeologist and Hebrew University professor Yosef Garfinkel argues that they show the face of Yahweh, the God of Israel. If accurate the sensational claim would mean both that ancient Israelites made idols (despite the strict biblical commands not to) and that we now have an early portrait of God. [Source: Candida Moss, The Daily Beast, July 31, 2020]

Drawings of the various heads that depict a large male head from the Kingdom of Judah, dated to the 10th-9th centuries BCE (drawing by Olga Dobovsky)

“The results of Garfinkel’s research were published this week in Biblical Archaeology Review. Three figurine heads were recently excavated from Khirbet Qeiyafa and Tel Mozạ, sites located close to the modern city of Jerusalem. (Garfinkel also refers to two other figurines, that were almost certainly looted, but BAR does not publish unprovenanced artifacts). Garfinkel argues that the discovery of some horse-like figurines close by to the heads from Mozạ shows that, originally, this anthropomorphic figure was a rider on a horse. For Garfinkel it’s clear that the image depicts an ancient deity. The question is, which one?

“There are several candidates up for the position. The Canaanite deity Baal (a rival of Yahweh’s in the Bible) is, as Nicholas Wyatt has written, repeatedly described as the “rider of the clouds” in ancient Ugaritic texts. Garfinkel argues, however, that the figure isn’t Baal but, rather, Yahweh. The same language of riding the clouds, he writes, appears in the Psalms, Deuteronomy, 2 Kings, Isaiah, and Habbukuk. Psalm 68:4 reads, “Sing to God, sing praises to his name; lift up a song to him who rides upon the clouds.”

“Which is it? Is the figurine Yahweh, the protector of Israel or Baal, the Canaanite storm God who enjoyed infant sacrifice? “The Canaanites,” writes Garfinkel “did not depict a male god on a horse. Only in Iron Age texts and iconography does the horse became a divine companion animal. So, the iconographic elements of the figurines correspond with descriptions of Yahweh in the biblical tradition.”

“Tenth and ninth century B.C. pilgrims, he argues, would have journeyed to cultic centers in order to see the face of Yahweh. Just as other ancient Near Eastern pilgrims were shown the face of God, so too devotees of Yahweh were able to see the face of the idol. This encounter between the pilgrim and the face of God, he writes, was an important religious experience and “metaphysical moment” in which heaven and earth are brought together.

Skeptics of the Claim of About the Early Portrait of God

Candida Moss, wrote in the Daily Beast: “One straightforward objection to Garfinkel’s hypothesis is that this is just the kind of thing that the Bible tells ancient Israelites not to do. Idols are expressly prohibited in a number of texts including the Ten Commandments. Maybe the references to seeing the face of God in the Hebrew Bible are strictly metaphorical? Drawing on earlier scholarship, Garfinkel argues that the ban on cultic images of Yahweh was not operative in the 10th century, when the figurines were in use, but was only introduced during the eight century B.C. [Source: Candida Moss, The Daily Beast, July 31, 2020]

“It’s a bold and eye-opening claim, but there are many who disagree. In an article published earlier this year, University of Tel Aviv scholars Shua Kisilevitz and Oded Lipschits, the archaeologists who oversee excavations at Tel Mozạ, argued something quite different about the temple where two of the figurines were found. While Kisilevits and Lipschits agree that the figurines are cultic objects, they do not believe that they are images of Yahweh. Noting parallels to the example from Khirbet Qeiyafa and other examples from the region, they describe them as “human figures” that were used in ritual practices in the temple at Tel Mozạ. They persuasively argue that the previously unknown temple at Mozạ was dedicated to the worship of a local Canaanite fertility deity. The cultic center in Jerusalem allowed the Canaanite temple to remain active because it produced a great deal of revenue. In sum, the figurines can’t be images of Yahweh, because this was never a temple dedicated to Yahweh.

“When it comes to interpreting the archaeology of ancient Israel, tensions run high. Lipschits regularly clashes with Garfinkel on matters of archaeological interpretation; in particular, Garfinkel’s pattern of linking all of his discoveries from the 10th century to biblical and national hero King David. In a recent interview on King David for the New Yorker, Lipschits said “Yossi Garfinkel is a prehistorian who hadn’t dealt with this period before, and he came into it with no real understanding.”

“This is more than just an academic disagreement turned public spat, however; the political and financial stakes are high. There are many, both Jewish and Christian, who are invested in the Bible’s narrative of conquest for political or religious reasons and sponsor excavations in the region. For these putative investors King David is more appealing than ancient Canaanite society. William Schniedewind, a professor at UCLA, intimated that these motivations may be at work when he told the New Yorker that Garfinkel’s excavations “have been seminal, but his interpretations sometimes are a little bit... Well, I mean, you need money, right?” The first season of Garfinkel’s excavations at Qeiyafa, for example, were sponsored by Foundation Stone, an organization that uses history to support a particular notion of Jewish identity.

“Prof. Robert Cargill, the editor of BAR and an archaeology professor at the University of Iowa, told The Daily Beast that the magazine’s mandate “is to report the claims made by professional archaeologists at licensed excavations in Israel… while [Garfinkel’s claims are] certainly a sensational interpretation and minority opinion, we felt obligated to publish the claim made by this tenured Hebrew University of Jerusalem professor of archaeology.” The jury is out on whether or not these figurines actually depict Yahweh, the God of Israel, but if they do we have learned something unexpected about the appearance of God. In addition to riding a horse, sporting a beard, and wearing his hair in a longish COVID-era style, he also has pierced ears.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except God heads from the Israel Antiquity Authority and Times of Israel

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Live Science, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024