Home | Category: The Old Testament

OLD TESTAMENT

Bible page from 1300

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon. It is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Israelites. The second division of Christian Bibles is the New Testament. Judaism does not accept the New Testament and refers to the "Old Testament" as the "Hebrew Bible". "Jewish Bible" or the Tanakh.

The original Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) was translated into Greek between the 3rd and 1st centuries B.C.. This translation is called the Septuagint (or LXX, both 70 in Latin), because there is a tradition that seventy Jewish scribes compiled it in Alexandria. It was quoted in the New Testament and is found bound together with the New Testament in the 4th and 5th century Greek uncial codices Sinaiticus, Alexandrinus and Vaticanus. The Septuagint included books, called the Apocrypha or Deuterocanonical by Christians, which were later not accepted into the Jewish canon of sacred writings

The Old Testament is essentially the story of a people and their relationship with God, written for and addressed to the same people. It is not all that different in its concept than the folklore and oral history of tribal peoples. The Old Testament also includes a wide range materials such as teachings of wise men, oracles, instructions of priests and ancient records of the royal courts. Some material is historical, some is legendary; some is legalistic, The word "Testament" is an archaic synonym to the word "covenant,” which means promise.

The term "Old Testament," or more properly "Old Covenant," is a Christian designation, reflecting the belief of the early Christian Church that the "new covenant" mentioned in Jer. 31:31-34 was fulfilled in Jesus and that the Christian scriptures set forth the "new covenant," just as the Jewish scriptures set forth the "old covenant" (II Cor. 3:6-18; Heb. 9:1-4). The Aramaic portions include Dan. 2:4b-7:28; Ezra 4:8-6:18, 7:12-26; Jer. 10:11; and one phrase in Gen. 31:47 "Jegar-sahadutha," translated "Heap of Witness.[Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,”1968, infidels.org ]

See Separate Article: OLD TESTAMENT, TORAH, TANAKH AND THE HEBREW BIBLE africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Bible and Biblical History: Bible Gateway and the New International Version (NIV) of The Bible biblegateway.com ; King James Version of the Bible gutenberg.org/ebooks ; Bible History Online bible-history.com ; Biblical Archaeology Society biblicalarchaeology.org ; Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Complete Works of Josephus at Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL) ccel.org ;

Judaism Judaism101 jewfaq.org ; Aish.com aish.com ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; torah.org torah.org ; Chabad,org chabad.org/library/bible ; Religious Tolerance religioustolerance.org/judaism ; BBC - Religion: Judaism bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/judaism ; Encyclopædia Britannica, britannica.com/topic/Judaism;

Jewish History: Jewish History Timeline jewishhistory.org.il/history ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Jewish History Resource Center dinur.org ; Center for Jewish History cjh.org ; Jewish History.org jewishhistory.org ;

Christianity and Christians Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Christianity.com christianity.com ; BBC - Religion: Christianity bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity/ ; Christianity Today christianitytoday.com

Books of the Old Testament

The Old Testament is comprised of 39 to 49 books, and roughly corresponds and is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible. The books contain the main texts of law, prophecy, history, and wisdom literature of ancient Israelites, mostly written in Hebrew but occasionally in Aramaic, a kindred language of Hebrew which came into common usage among the Jews during the post-Exilic era (after the sixth century B.C.). [Source: Wikipedia]

Most of the books in the 39-book Old Testament-Tankh were written in Hebrew between 1200 and 100 B.C. The New Testament was written in the Koine Greek language.

The Old Testament is comprised of many books written by numerous authors over a period of centuries.. The Old Testament has traditionally been divided by Christians into four sections: 1) The Pentateuch, the first five books which corresponds to the Jewish Torah; 2) the historical books, describing the history of the Israelites, from their occupation of Canaan to their exile in Babylon); 3) the poetic “wisdom” books (questions of good and evil in the world); and 4) the biblical prophets, which warn of the consequences of turning away from God. [Source: Pedia.com]

Book and Text Differences Among Old Testaments of Different Christian Groups

The books that make up the Old Testament canon and their order and names differ between the different branches of Christianity. The canons of the Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox Churches is comprised of 49 books; the Catholic canon has 46 books; and the most common Protestant canon has 39 books, which are essentially found in all Christian canons.

There are some differences in text. The different numbers of books reflects the splitting of several texts (Samuel, Kings, Chronicles, Ezra–Nehemiah, and the Twelve Minor Prophets) into separate books in Christian Bibles. These books are part of the Christian Old Testament but that are not part of the Hebrew canon are sometimes described as deuterocanonical books. Generally speaking, Catholic and Orthodox churches include these books in the Old Testament while most Protestant Bibles do not. Some versions of Anglican and Lutheran Bibles place these books in a separate section called apocrypha. These books are ultimately derived from the earlier Greek Septuagint collection of the Hebrew scriptures and are also Jewish in origin. Some are also contained in the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Pentateuch — First Five Books of the Old Testament

Samaritan high priest with and Old Pentateuch, 1905

The Pentateuch is the First Five Books of the Bible, which is also The Torah and the first five books of the Tanakh (Jewish Bible) and Old Testament. "Penta" means five in Greek. The word “Pentateuch” is derived from the Greek word pentateuchos, which means “five-volume work.”

The first five books of the Bible and Tanakh are: 1) Genesis (Bereshit),is named for the Hebrew word for “in the beginning.” Itt describes the creation of the world, the birth of Adam and Eve, the fall of mankind, and the generations of Adam, including Noah and Cain and Abel. It ends with Joseph’s sale into slavery in Egypt. 2) Exodus (Shemot) narrates the story of the Israelites’ suffering in Egypt, their liberation by Moses, their journey to Mount Sinai, and their wanderings in the wilderness. 3) Leviticus (Vayikrah) focuses mainly on priestly matters, offering instructions for rituals, sacrifices, and atonement, but not on the history of the Jewish people. 4) Numbers (Bamidbar) depicts the wanderings of Israelites in the wilderness as they journey toward the promised land in Canaan. 5) Deuteronomy (Devarim).narrates the end of the journey and ends with Moses’ death just before they enter the promised land.

The five books of the Pentateuch were named by the Jews of Palestine according to the opening Hebrew words: 1) Bereshith: "in the Beginning" 2) We'elleh Shemoth: "And these are the names" 3) Wayyiqra': "And he called" 4) Wayyedabber: "And he spoke" 5) Elleh Haddebarim: "These are the words" [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

“The names now used in the English translations are from the Septuagint (Greek Old Testament): 1) Genesis means the beginnings of the world and of the Hebrew people 2) Exodus describes the departure from Egypt under Moses 3) Leviticus encompasses: legal rulings concerning sacrifice, purification, and so forth of concern to the priests, who came from the tribe of Levi 4) Numbers (Arithmoi) refers the numbering or taking census of Israelites in the desert 5) Deuteronomy: means"second law," because many laws found in the previous books are repeated here

Catholic, Orthodox, Protestant, Jewish Books of the Old Testaments

The Protestant Old Testament has 39 books. The Catholic Old Testament has 46 books). The Eastern Orthodox Old Testament has 49 books. The Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) has 24 books. Several of the books in the Eastern Orthodox canon are also found in the appendix to the Latin Vulgate, formerly the official Bible of the Roman Catholic. [Source: Wikipedia Wikipedia ]

Pentateuch, Torah (Law) the Five books of Moses

Protestant —— Catholic —— Orthodox —— Tanakh —— Original language

Genesis —— Genesis —— Genesis —— Bereshit —— Hebrew

Exodus —— Exodus —— Exodus —— Shemot —— Hebrew

Leviticus —— Leviticus —— Leviticus —— Vayikra —— Hebrew

Numbers —— Numbers —— Numbers —— Bamidbar —— Hebrew

Deuteronomy —— Deuteronomy —— Deuteronomy —— Devarim —— Hebrew

Historical books (Nevi'im (Prophets))

Protestant —— Catholic —— Orthodox —— Tanakh —— Original language

Joshua —— Joshua (Josue) —— Joshua (Iesous) —— Yehoshua —— Hebrew

Judges —— Judges —— Judges —— Shoftim —— Hebrew

Ruth —— Ruth —— Ruth —— Rut (Ruth) —— Hebrew

1 Samuel —— 1 Samuel (1 Kings) —— 1 Samuel (1 Kingdoms) — Shmuel —— Hebrew

2 Samuel —— 2 Samuel (2 Kings) —— 2 Samuel (2 Kingdoms) —— Shmuel — Hebrew

1 Kings —— 1 Kings (3 Kings) —— 1 Kings (3 Kingdoms) — Melakhim —— Hebrew

2 Kings —— 2 Kings (4 Kings) —— 2 Kings (4 Kingdoms) —— Melakhim — Hebrew

1 Chronicles —— 1 Chronicles (1 Paralipomenon) —— 1 Chronicles (1 Paralipomenon) —— Divrei Hayamim (Chronicles) —— Hebrew

2 Chronicles —— 2 Chronicles (2 Paralipomenon) —— 2 Chronicles (2 Paralipomenon) —— Divrei Hayamim (Chronicles) —— Hebrew

Ezra —— Ezra (1 Esdras) —— Ezra (2 Esdras) — Ezra–Nehemiah —— Hebrew and Aramaic

Nehemiah —— Nehemiah (2 Esdras) —— Nehemiah (2 Esdras) —— Ezra–Nehemiah— Hebrew

Esther —— Esther —— Esther —— Ester (Esther) —— Hebrew

1 Maccabees (1 Machabees) —— 1 Maccabees —— —— Hebrew and Greek

Tobit (Tobias, Aramaic and Hebrew), Judith (Hebrew) and 2 Maccabees (2 Machabees, Greek)are only in the Catholic and Orthodox Old Testaments. 1 Esdras, 3 Esdras, 3 Maccabees and 4 Maccabees — all originally in Greek are old in the Orthodox Old Testament.

Wisdom books (Ketuvim (Writings))

Protestant —— Catholic —— Orthodox —— Tanakh —— Original language

Job —— Job —— Job —— Iyov (Job) —— Hebrew

Psalms —— Psalms —— Psalms —— Tehillim (Psalms) —— Hebrew

Proverbs —— Proverbs —— Proverbs —— Mishlei (Proverbs) —— Hebrew

Ecclesiastes —— Ecclesiastes —— Ecclesiastes —— Qohelet (Ecclesiastes) —— Hebrew

Song of Solomon —— Song of Songs (Canticle of Canticles) —— Song of Songs (Aisma Aismaton) —— Shir Hashirim (Song of Songs) —— Hebrew

Wisdom (Greek) and Sirach (Ecclesiasticus, Hebrew) are only in the Catholic and Orthodox Old Testaments. Prayer of Manasseh (Greek) is only in the Orthodox Old Testament.

Major Prophets (Nevi'im (Latter Prophets))

Protestant —— Catholic —— Orthodox —— Tanakh —— Original language

Isaiah —— Isaiah (Isaias) —— Isaiah —— Yeshayahu —— Hebrew

Jeremiah —— Jeremiah (Jeremias) —— Jeremiah —— Yirmeyahu —— Hebrew

Lamentations —— Lamentations —— Lamentations —— Eikhah (Lamentations) —— Hebrew

Ezekiel —— Ezekiel (Ezechiel) —— Ezekiel —— Yekhezqel —— Hebrew

Daniel —— Daniel —— Daniel —— Daniyyel (Daniel) —— Aramaic and Hebrew

Baruch (Hebrew) is only in the Catholic and Orthodox Old Testaments.

Letter of Jeremiah (Greek) is only in the Orthodox Old Testamentl

Twelve Minor Prophets (In the Tanakh all are included in The Twelve (Trei Asar))

Protestant Catholic Orthodox Original language

Hosea —— Hosea (Osee) —— Hosea —— Hebrew

Joel —— Joel —— Joel —— Hebrew

Amos —— Amos —— Amos —— Hebrew

Obadiah —— Obadiah (Abdias) —— Obadiah —— Hebrew

Jonah —— Jonah (Jonas) —— Jonah —— Hebrew

Micah —— Micah (Michaeas) —— Micah —— Hebrew

Nahum —— Nahum —— Nahum —— Hebrew

Habakkuk —— Habakkuk (Habacuc) —— Habakkuk —— Hebrew

Zephaniah —— Zephaniah (Sophonias) —— Zephaniah —— Hebrew

Haggai —— Haggai (Aggaeus) —— Haggai —— Hebrew

Zechariah —— Zechariah (Zacharias) —— Zechariah —— Hebrew

Malachi —— Malachi (Malachias) —— Malachi —— Hebrew

Translations of the Old Testament

<br/> The Old Testament was composed and edited by members of the Hebrew-Jewish community between the twelfth century B.C. and the beginning of the Christian era. It Gerald Larue wrote: “As Hebrew and Aramaic continued to be living languages during the first 500 years of the Christian era, there was little cause for concern about proper reading of the text. When these languages began to die, a group of Jewish scholars known as Massoretes8 came into being in Babylon and Palestine. Their work embraces a period roughly between A.D. 600 and 1000. They were, in a sense, successors to the scribes and deeply concerned with the purity and preservation of the text, but their efforts extended beyond care in copying because of the emergence of new problems. The Hebrew text had been written without any division between words. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,”1968, infidels.org ]

<br/> The Old Testament was composed and edited by members of the Hebrew-Jewish community between the twelfth century B.C. and the beginning of the Christian era. It Gerald Larue wrote: “As Hebrew and Aramaic continued to be living languages during the first 500 years of the Christian era, there was little cause for concern about proper reading of the text. When these languages began to die, a group of Jewish scholars known as Massoretes8 came into being in Babylon and Palestine. Their work embraces a period roughly between A.D. 600 and 1000. They were, in a sense, successors to the scribes and deeply concerned with the purity and preservation of the text, but their efforts extended beyond care in copying because of the emergence of new problems. The Hebrew text had been written without any division between words. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,”1968, infidels.org ]

Because Hebrew and Aramaic had become dead languages, the words were separated to give ease in reading. To keep the text constant, the Massoretes developed mechanical checks and counted the number of words and letters, noted the number of times the divine name was used or special words appeared, and determined the middle verses, words and letters of individual books. Any manuscript that failed on any of these counts was defective.

See Separate Article Translations of the Bible africame.factsanddetails.com

Development of the Christian Old Testament

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “The contents of the Law and the Prophets had been determined by usage in the Jewish community prior to the LXX translation, but the limits of the Kethubhim had not been defined and books were included that were not to achieve canonical status among all Jews.4 When the Christian Church began to move into the Greek-speaking world during the first century A.D., the scripture used by the missionaries was the LXX. The authors of the New Testament Gospels drew upon the LXX to prove that Jesus was the Messiah and the fulfillment of Jewish prophecy, using some passages which the Jews argued had been inadequately translated from the Hebrew to the Greek (particularly Isaiah 7:14; compare with Matt. 1:23). The destruction of the Temple by the Romans in 70 A.D. gave Judaism a new direction, centering in scripture rather than sacrificial rites, so that it became imperative to define the limits of the authoritative writings. Consequently, in 90 A.D. at Jamnia (Jabneh) , situated west of Jerusalem near the Mediterranean, a council met under the leadership of Rabbi Johanan ben Zakkai to determine the Jewish canon. Long debates ensued over the Song of Songs, Esther, Ecclesiastes, and Ezekiel. The books agreed upon by the Council constitute the Jewish canon of today. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

Concerning other writings, both Jewish and Christian, the Council stated: “The Gospel and the books of the heretics are not Sacred Scripture. The books of Ben Sira and whatever books have been written since his time, are not Sacred Scripture. (Tosef Yadaim 2:13).“Meanwhile the Christians continued to use the LXX including books of the Apocrypha rejected by the Jamnia Council. There was, however, some uneasiness among Christian scholars concerning certain of the books and just prior to the Protestant Reformation questions were being raised about the authority of the Apocrypha. Seeking to go back to ancient sources, Protestant reformers accepted the Jewish canon and relegated the Apocrypha to the status of writings without authority for doctrine, partially, no doubt, because certain unacceptable doctrines were based upon these writings. For Protestants, the writings of the Apocrypha are separated from canonical scriptures and held to be non-authoritative for doctrine.

“The Roman Catholic Church took the opposite stand at the Council of Trent held in Tridentum, Italy from 1545 to 1563 and, partially on the basis of traditional usage among Christians, declared the books of the Apocrypha, with the exception of I and II Esdras and the prayer of Manasseh, to be canonical and pronounced anathema upon all who denied their status. The accepted books are labeled "Deuterocanonical"6 by Roman Catholic scholars who restrict the use of the term "Apocrypha" to designate writings purporting to be inspired but not accepted into the Roman Catholic canon. The latter writings are labeled "Pseudepigrapha" (False Writings) by Protestant scholars. Later, in 1672, at the Council of Jerusalem, the Eastern Orthodox Church accepted I Esdras, Tobit, Judith, the Wisdom of Solomon, Ecclesiasticus, Baruch, the Prayer of Azariah and The Song of the Three Young Men, Bel and the Dragon, and I and II Maccabees into the canon, for reasons that are not completely clear.

“Thus, the term "Old Testament" has a wider and a narrower meaning, depending upon who uses it. This book will discuss the literature common to Jewish, Protestant, Roman Catholic, and Eastern Orthodox Bibles, and the writings called the "Apocrypha" by Protestants and Jews or "Deuterocanonical" by Roman Catholics.

Bible Development Timelines

From Many Books to the One Book

Mark Hamilton, a Biblical scholar at Harvard University, wrote: “How did these various pieces come to be regarded as Scripture by Jewish and, later, Christian communities? There were no committees that sat down to decree what was or was not a holy book. To some degree, the process of Scripture-making, or canonization as it is often called (from the Greek word kanon, a "measuring rod"), involved a process, no longer completely understood, by which the Jewish community decided which works reflected most clearly its vision of God. The antiquity, real or imagined, of many of the books was clearly a factor, and this is why Psalms was eventually attributed to David, and Proverbs, Song of Songs, and Ecclesiastes (along with, by some people, Wisdom of Solomon in the Apocrypha) to Solomon. However, mere age was not enough. There had to be some way in which the Jewish community could identify its own religious experiences in the sacred books. [Source: Mark Hamilton, Harvard University Biblical scholar, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“This occurred, at least in part, through an elaborate process of biblical interpretation. Simply reading a text involves interpretation. Interpretative choices are made even in picking up today's newspaper; one must know the literary conventions that distinguish a news report, for example, from an op-ed piece. The challenge becomes much more intense when one reads highly artistic texts from a different time and place, such as the Bible.

“The earliest examples of interpretation we have appear in the Bible itself. Zechariah reinterprets Ezekiel, Jeremiah often refers to Hosea and Micah, and Chronicles substantially rewrites Kings. These reinterpretations are in themselves evidence that the older books were already becoming authoritative, canonical, even as the younger ones were still being written.

“But some of the oldest extensive reinterpretations of our Bible come from the third or second centuries BCE. For example, the book of Jubilees is a rewriting of Genesis, now arranged in 50-year periods ending in a year of jubilee, or a time for forgiveness of debts. A related work is the Genesis Apocryphon, also a rewriting of Genesis. Ezekiel the Tragedian wrote a play in Greek based on the life of Moses. And the Essenes, the sect that produced the Dead Sea Scrolls, composed commentaries (peshers) on various biblical books: fragments of those on Habakkuk, Hosea, and Psalms survive. From the first century BCE or so, come additional psalms attributed to David and the Letter of Aristeas (about the miraculous translating of the Bible into Greek), among others. And during the life of Jesus himself, Philo of Alexandria wrote extensive allegorical commentaries on the Pentateuch, all with a view toward making the Bible respectable to philosophers influenced by Plato.

“Despite their great variety of outlook and interests, all of these works shared certain common views. They all believed the author of the Bible was God, that it was therefore a perfect book, that it had strong moral agendas and that it was abidingly relevant. Interpretation had to show how it was relevant to changing situations. They also thought the Bible to be cryptic, a puzzle requiring piecing together. The mental gymnastics required to make the old texts ever new is one of the great contributions of this era to the history of Judaism and Christianity, and therefore Western civilization itself.

Example of Interpretation: Genesis 11

Mark Hamilton, a Biblical scholar at Harvard University, wrote: “Genesis 11 is the story of how humans soon after the Flood built a city centered around a tower "with its top in the heavens." The purpose of the Tower of Babel was to allow its builders to "make a name" for themselves. God, in a pique of anger, alters the builders' languages so that they cannot understand each other. In its original form, the story is an explanation of why not everyone speaks Hebrew, as well as a comment on the huge temple-towers (ziggurats) of Mesopotamian cities. [Source: Mark Hamilton, Harvard University Biblical scholar, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“For later interpreters, however, this story cried out for explanation. Why was God afraid of these people? How high was the tower? Who led the construction, and did anyone voice objections? What did the builders expect to do when they reached the heavens? What moral lessons should one learn from the story?

“To answer these questions and others, Jubilees 10 says that the builders worked for 43 years (50 years of the Jubilee period minus the mystical number seven) and built a structure one and a half miles high! Their purpose was to enter into heaven itself. Pseudo-Philo's Biblical Antiquities (first century CE) adds a story about Abraham, a model of courage, refusing to cooperate with the builders and so being thrown into a fiery furnace, much like the three young men in Daniel 3. God sends an earthquake to destroy the furnace, and then he changes both the builders' languages and their appearance, so that no one can recognize even his or her own brother. Other traditions think that the builders of the tower were either giants (Pseudo-Eupolemus), or were humans led by the mighty hunter and city-builder Nimrod mentioned in Genesis 10 (Josephus). Each interpreter imaginatively builds on some chance word or phrase in the biblical text to try to answer reasonable questions about it. Meanwhile, the first-century philosopher and biblical interpreter writes an entire book on this chapter, which he interprets as an allegory about human morality: the builders represent greed and venality.

Addressing the Messiah Issue

Mark Hamilton, a Biblical scholar at Harvard University, wrote: “Like their Jewish predecessors and Jewish contemporaries, early Christians believed that the Hebrew Bible was God's book, and therefore a book that should cast light on current events and moral conundrums. For Christians, of course, the most important issue was the true import of Jesus and the story of his life, death, and resurrection. Since they believed him to be the messiah ("anointed one"), God's savior and the harbinger of a new and perfect age, they sought to find mention of him in the Hebrew Bible itself. This is why so much of the story of Jesus in the gospels quotes the Bible. [Source: Mark Hamilton, Harvard University Biblical scholar, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“This move was not without precedent. The Dead Sea community also believed that the prophets had predicted their movement and their leader, the Teacher of Righteousness, as well as the political events of their time. They go so far as to claim that the prophets did not know what they were saying, but God, the true author of the text, used them to speak of the (to them) distant future.

“Christians, however, had a different set of questions than the Dead Sea sect, and so they found different texts to cite. Any texts that refer to a time of a future deliverance, or the coming of a future king, were fair game. So the suffering servant of Isaiah 53 becomes the suffering Jesus of the gospels. And Luke's quotation from Isaiah 61 becomes a reference to Jesus's ministry of healing and reconciliation. Yet in every case, as far as we can tell, the Christian reading comes after the fact. That is, they first believed in Jesus and then tried to find his life in Scripture. They then could shape their telling of stories about his life to fit the scriptures. This process may seem very circular, but given their assumptions — namely, that Jesus is central to God's plan, that God spoke through prophets who might not understand their own words, and that the Bible was a cryptic puzzle needing solving — this belief in prophecy and fulfillment is not incomprehensible. So Luke can have Jesus say, "Today this Scripture is fulfilled in your presence!" Jesus saw himself as the deliverer that the prophets had foreseen long before. When his followers drew the same conclusion, they could then retain the ancient Scriptures, transforming them into something new, a Christian Bible.

Old Testament Apocrypha

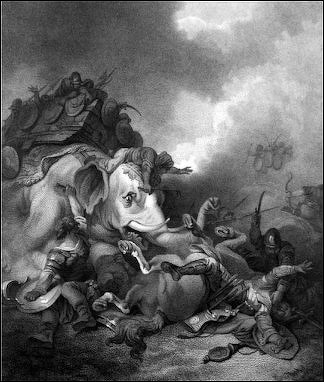

Apocrypha scene: Fraud of the Priests of Bel

Works not accepted as canonical are called "Apocrypha." Old Testament Apocrypha (or Deuterocanon) designates several, unique writings (e.g., the Book of Tobit) or different versions of pre-existing writings (e.g., the Book of Daniel) found in the canon of the Jewish scriptures (most notably, in the Septuagint translation of the Hebrew Tanakh). Although those writings were no longer viewed as having a canonical status amongst Jews by the beginning of the second century A.D., they retained that status for much of the Christian Church. They were and are accepted as part of the Old Testament canon by the Catholic Church and Eastern Orthodox churches. Protestant Christians, however, follow the example of the Jews and do not accept these writings as part of the Old Testament canon.

Catholic Bibles include some non-Tanakh works from Jewish sources, but they were relatively late in time and were often written in Greek or Aramaic, and not in Hebrew. Jewish sages did not include any of these books in the official ‘canon’, mostly for that reason. These ‘extra’ books are sometimes called ‘Deutero-canonical’ (Secondarily canonical). Gold Hunter wrote: Some editions take parts of those writings and just stick them onto the original (older) Hebrew books — additions to (off the top of my head here) Daniel I think, maybe Esther too. When Martin Luther decided to translate the Bible (OT and NT) into German, he decided to use the Jewish versions, rather than the Latin Catholic Bible for his source for the OT.

Apocrypha are usually of unknown authorship or of doubtful origin. Biblical apocrypha is a set of texts included in the Latin Vulgate and Septuagint but not in the Hebrew Bible. While Catholic tradition considers the texts to be deuterocanonical, Protestants consider them apocryphal. Thus, Protestant bibles do not include the books within the Old Testament but have often included them in a separate section. Other non-canonical apocryphal texts are generally called pseudepigrapha, a term that means "false writings". The word's origin is the Medieval Latin adjective apocryphus, "secret, or non-canonical", from the Greek adjective apokryphos ("obscure"), from the verb apokryptein ("to hide away"). [Source: Wikipedia]

1 Esdras

2 Esdras

1 Maccabees

2 Maccabees

3 Maccabees

4 Maccabees

Letter of Jeremiah

The Prayer of Azariah

Baruch

[Source: pseudepigrapha.com]

Prayer of Manassas

Bel and the Dragon

Wisdom of Sirach

Wisdom of Solomon

Additions to Esther

Tobit

Judith

Susanna

Psalm 151

Pseudepigrapha

Pseudepigrapha are falsely-attributed works, texts whose claimed author is not the true author, or a work whose real author attributed it to a figure of the past. In biblical studies, the term generally refers to an assorted collection of Jewish religious works thought to be written c. 300 BC to 300 AD. They are distinguished by Protestants from the Deuterocanonical books (Catholic and Orthodox) or Apocrypha (Protestant), the books that appear in extant copies of the Septuagint from the fourth century on, and the Vulgate but not in the Hebrew Bible or in Protestant Bibles. [Source: Wikipedia]

Pseudepigraphic works are considered to be fiction. Because of that stigma, they are not included in the compilation of the Holy Bible. Historians like pseudepigraphic because such works often carry significant meaning and insight into events of the time they were written. . It is doubtful that these writings could have survived the many centuries they did if there were no substance to them.

Apocrypha scene: Heroism of Eleazar

Pseudepigrapha Texts include:

The Books of Adam and Eve -- translation of the Latin version

Life of Adam and Eve -- translation of the Slavonic version

Life of Adam and Eve -- translation of the Greek version (a.ka. The Apocalypse of Moses)

The Apocalypse of Adam

The Book of Adam

The Second Treatise of the Great Seth

1 Enoch (Ethiopic Apocalypse of Enoch)

1 Enoch Composit (inc. Charles, Lawrence & others)

2 Enoch (Slavonic Book of the Secrets of Enoch)

Enoch (another version)

Melchizedek

The Book of Abraham

The Testament of Abraham

The Apocalypse of Abraham

The Story of Asenath

[Source: pseudepigrapha.com]

Selections from The Book of Moses

Revelation of Moses

The Assumption of Moses (aka: The Testament of Moses)

The Martyrdom of Isaiah

The Ascension of Isaiah

The Revelation of Esdras

The Book of Jubilees

Tales of the Patriarchs

The Letter of Aristeas

The Book of the Apocalypse of Baruch (aka: 2 Baruch)

The Greek Apocalypse of Baruch (aka: 3 Baruch)

Fragments of a Zadokite work (aka: The Damascus Document)

The Testament of Solomon

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons except Bible Development Timelines, Relevancy 22 and New Testament Canon, Bible Diagrams

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, King James Version of the Bible, gutenberg.org, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com Complete Works of Josephus at Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL), translated by William Whiston, ccel.org , Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994); National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated February 2024