Home | Category: The Old Testament

TRANSLATIONS OF THE OLD TESTAMENT

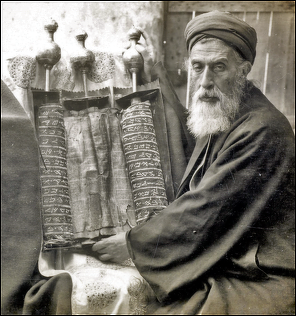

Samaritan high priest with and Old Pentateuch, 1905

Larue wrote: “As Hebrew and Aramaic continued to be living languages during the first 500 years of the Christian era, there was little cause for concern about proper reading of the text. When these languages began to die, a group of Jewish scholars known as Massoretes8 came into being in Babylon and Palestine. Their work embraces a period roughly between A.D. 600 and 1000. They were, in a sense, successors to the scribes and deeply concerned with the purity and preservation of the text, but their efforts extended beyond care in copying because of the emergence of new problems. The Hebrew text had been written without any division between words.9 Because Hebrew and Aramaic had become dead languages, the words were separated to give ease in reading. To keep the text constant, the Massoretes developed mechanical checks and counted the number of words and letters, noted the number of times the divine name was used or special words appeared, and determined the middle verses, words and letters of individual books. Any manuscript that failed on any of these counts was defective. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,”1968, infidels.org ]

“Efforts were made to correct scribal errors, although some "corrections" appear to have been made on dogmatic grounds.10 The Hebrew text had been recorded without vowels.11 The Massoretes invented a vowel system which was added to the text to preserve correct pronunciation. Where the Massoretes questioned the reading, special notations were added, and the Massoretes distinguished between Kethib, what is written, and Qere, what is to be read. Perhaps the best known alteration was the placing of the vowels of 'Adonai under the tetragrammaton YHWH, indicating that although the name is written YHWH ( Kethib) it is to be read 'Adonai ( Qere). Most other notations of this kind rest upon grammatical rather than dogmatic reasoning. Massoretic notes placed in the margins of manuscripts became so extensive that they had to be compiled separately.

“Not all Massoretic traditions were in agreement. Babylonian scholars had developed a vowel system that differed from that of the Palestinian or Tiberias school. Because the Palestinian pattern prevailed, manuscripts with other notations fell into disrepute and began to disappear. Two of the most famous and most authoritative manuscripts by Palestinian Massoretes are from the tenth century: one by Moses ben David ben Naphtali is known as "ben Naphtali," and the other by Aaron ben Moses ben Asher is known as "ben Asher." The ben Asher text, the product of a family of Massoretes, is preferred and is the basic Hebrew text used by scholars and translators. The Massoretic text is designated by the letter M.”

Early Translations of the Old Testament

Larue wrote: “The first translation of Jewish religious writings out of the Hebrew and Aramaic, the LXX, was the product of several different translators.13 Unfortunately no early copies of the LXX remain, and those we do have were preserved by the Christian Church. Some manuscripts contain alteration by those who wished to make certain passages sustain Christian beliefs. By the middle of the fourth century, the LXX had become sadly corrupted. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,”1968, infidels.org ]

“During the second century A.D., Aquila, a Jewish proselyte from Pontus and a pupil of Rabbi Akiba, made a Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures. Although Greek was his native tongue, he chose to make a stilted word-for-word translation that imitated Hebrew language patterns and perpetrated outrages on the structure of the Greek language. Because of his anti-Christian attitude, Aquila translated certain passages differently from the LXX, rendering them unusable for Christian doctrine. For example, he translated bethulah in Isa. 7:14 as "young woman" ( neanis) rather than "virgin" ( parthenos) and avoided the Greek term christos as a translation of the Hebrew word for "anointed." In 1897, a collection of manuscripts from the genizah of the old Cairo Synagogue was found to include a palimpsest,14 Containing portions of Aquila's work dated in the fifth century A.D.

“Theodotion, a follower of Marcion according to Epiphanus (a fourth century writer), or an Ebionite15 according to Jerome, revised the LXX, or some text closely approximating it, during the second century. Theodotion's version was closer to M than to the LXX. Only fragments remain of the work of Symmachus who, near the end of the second century, made a Greek translation from the Hebrew text. According to Jerome, Symmachus was an Ebionite, but Epiphanus says he was a Samaritan who became a Jewish proselyte. Symmachus consulted various Greek versions in preparing his work.

“As Christianity reached into new areas of the world, it became more and more important to provide converts with the Bible in their own language and dialect. The ancient Syrian Church produced a translation known as the Peshitta, a term that may be derived from a word meaning "common" or perhaps "simple." The Peshitta is relatively close to the Hebrew text but reflects the influence of Jewish targums.16 “During the third century, Origen composed the Hexapla in an attempt to harmonize Greek and Hebrew versions. The text was written in six parallel columns. The first contained the Hebrew text; the second, the Hebrew text translated into Greek; the third, Aquila's version; the fourth Symmachus' translation; the fifth, the LXX and the sixth, Theodotion's version. The fifth column was, in reality, a new text, an adaption of the LXX, and only contributed to the textual confusion.

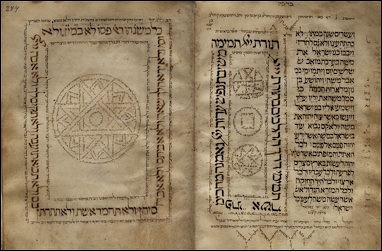

Pentateuch with vocalizations and cantillation marks

“Perhaps the most important translation was the Latin Vulgate ("common"). In response to an appeal by Pope Damasus, Jerome, the great Christian scholar of the late fourth and early fifth centuries, undertook a revision of the Latin Bible. His work relied heavily upon the Hebrew text, but in some places Jerome drew upon the LXX to support Christian beliefs. For example, he retained the word "virgin" in Isa. 7:14. His translation met with strong opposition but ultimately found favor and became the official Bible of the Roman Catholic Church.

“A Coptic version was prepared during the fourth century to meet the needs of Christian converts in upper Egypt. Ethiopian, Armenian, Gothic, Slavonic, Georgian and Arabic translation were made. The scroll form had been virtually abandoned by this time in favor of the codex or book form. Three of the most important Greek codices are Sinaiticus, Vaticanus and Alexandrinus, all representing texts which probably originated in Egypt.

“When, during the early years of the fourth century A.D., the Emperor Constantine made Christianity an officially sanctioned religion, the Church entered one of its periods of great expansion. Helena, mother of Constantine, was devoted to commemorating religious sites. Her interest led her to determine the precise place on Mount Sinai where God had revealed himself to Moses in the burning bush, and there she erected a tower. Nearly two hundred years later, the Emperor Justinian built a church on the site, which was to become the Convent of St. Catherine. The convent became a popular place for pilgrimages, and those who came brought precious manuscripts to swell the rich library.”

Going Back to the Early Translations

Larue wrote: “In the middle of the nineteenth century, a famous German textual scholar, Constantin Tischendorf, became convinced that ancient manuscripts were preserved in the libraries of Greek, Syrian, Coptic and Armenian monasteries. His search led him to St. Catherine's, and there he found a fourth century A.D. manuscript known as Codex Sinaiticus.17 This codex is composed of pages fifteen by thirteen-and-a-half inches, with four narrow columns of writing per page, except for the poetic books, which have only two columns per page. There are no word divisions. The hands of three scribes can be discerned, largely on the basis of spelling variations. Of the estimated original 730 pages, 390 pages remain of which 242 belong to the Old Testament. Codex Sinaiticus was sent to Russia, where it remained until it was sold to the British Museum for $500,000 in December, 1933. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,”1968, infidels.org ] “An earlier fourth century codex, known as Codex Vaticanus, was also of great interest to Tischendorf. The Vatican library was established by the scholar Pope Nicholas V in 1448. just how the fourth century codex came into the possession of the library is not known, for it is first listed in a catalogue made in 1475. It had always been considered of extreme value and importance, but because of restrictive rules, was available solely to scholars officially connected with the Vatican. Napoleon had removed it to Paris, where it remained until 1815 before being returned to Rome, but no one appears to have taken advantage of its availability.

“Tischendorf made two attempts to see the manuscript. The first in 1843 failed. The second, in 1866, succeeded, for by this time Tischendorf had won fame as the discoverer and publisher of Codex Sinaiticus. Contrary to his agreement with Vatican authorities, Tischendorf copied and published some pages of the codex. Soon restrictive policies were relaxed and an official photographic copy was released in 1890. Codex Vaticanus contains 759 leaves, and from the Old Testament only the first forty-six chapters of Genesis and Psalms 106 to 138 are missing. Vaticanus is, perhaps, the most valuable of all Greek manuscripts of the Bible.

“The history of Codex Alexandrinus is obscure. In 1624, it was offered by the Patriarch of Constantinople to King James I of England. James died before it arrived, and it was received by Charles I. It remained in the possession of the royal family until George II gave it to the British Museum. Alexandrinus is dated in the fifth century and is only slightly less significant than Vaticanus and Sinaiticus. About fifty pages appear to have been lost, but 630 pages of the Old Testament remain.

Translations of the Bible into English

Larue wrote: “The story of the English Bible is marred by tragedy, martyrdom, tyranny, bigotry and other aspects of human misunderstanding, stupidity and greed. The account can only be sketched here, but there are many excellent books that tell the story in detail. Christianity was brought to England in the second century, but the expansion of the faith did not occur until near the end of the sixth century. It can be assumed that Latin versions of the Bible were in the possession of monks and that the "message" of the Bible was conveyed to the non-reading laity through sermons and other modes of teaching. During the early years of the eighth century, the Venerable Bede, a monk of Jarrow, recorded the story of Caedmon, a gifted monk of the seventh century who made poetic paraphrases of biblical themes in Anglo-Saxon. The few fragments of his work that have been preserved make it impossible to call his efforts "translations," although they do represent an attempt to make the contents of the Bible known to the masses in their own language. Bede was also a translator of the Bible, but nothing remains of his work. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,”1968, infidels.org ]

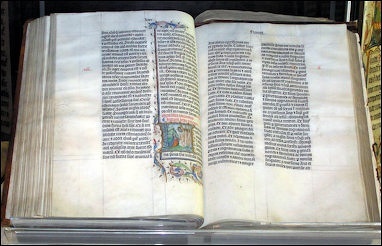

Malmesbury Bible

“Toward the end of the seventh century, a certain Aldhelm, who became Bishop of Sherborne, translated the Psalms into Anglo-Saxon. An eleventh century manuscript in Paris is supposed to be based on his work. King Alfred (ninth century) is reported to have continued the work of Bede and Aldhelm and to have affixed to his own laws parts of the Mosaic code, including the Decalogue. He was supposed to have been engaged in the translation of the Psalms at the time of his death. Unfortunately, none of his writings has survived.

“There is only limited information concerning English translations before the fourteenth century. The Abbot Aelfric summarized parts of the Bible in Anglo-Saxon in his sermons, and one of his manuscripts is in the British Museum. Following the Norman conquest (eleventh century), William of Shoreham and Richard Rolle made separate translations of the Psalter. By this time Anglo-Saxon, influenced by new words imported from the continent, was becoming the English language. Like their predecessors, William of Shoreham and Rolle based their translations on the Vulgate. A most important contribution to Bible study was made by Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury, who, about 1205, introduced chapter divisions into the Latin Bible. It was not until 1330 that these divisions were first applied to the Hebrew version.

“Through John Wycliffe (also spelled Wickliffe, Wyclif, etc.) and his Oxford associate Nicholas of Hereford (fourteenth century), great strides were taken in Bible translation.19 This was the age of Chaucer, a time of literary and cultural growth. Hereford was responsible for translating most of the Old Testament from the Latin, but his work terminates abruptly at Baruch 3:19. During the early fifteenth century, John Purvey, a friend and disciple of Wycliffe, revised the Hereford-Wycliffe edition to produce a smoother, more readable work which became extremely popular. Wycliffe's Bible was proscribed in 1408 by Archbishop Arundel, and in 1414 a law was passed stating that those found reading the Bible in their own language "should forfeit land, catel, lif, and goods." Despite legislation, the burning of Bibles and killing of readers, the Bible continued to be copied and read.

Translations of the Bible During the Renaissance and Reformation

Larue wrote: “The second half of the fifteenth century introduced a period of change in Europe that has been labeled the Renaissance. Men became increasingly aware of "the world" through new explorations by travelers, scientists and thinkers. It was the century of Columbus, Copernicus and Leonardo da Vinci. In 1453, when Constantinople fell to the Turks, scholars from that great center of learning fled to Europe, introducing classical knowledge of the ancient world. The Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492 and five years later from Portugal, and they moved northward in Europe, revitalizing interest in the Hebrew Scriptures and Jewish scholarship. It was also the era of the Protestant reformation. Most important for the literary world was the discovery of the means of printing, using movable type. Now rapid and cheap reproductions of written works, including the Bible, became possible. The first printed Bible, a Latin version, appeared in 1456 and is attributed to Henne Gensfleich or, as lie is better known by his assumed name, Johann Gutenberg (Gutenberg was his mother's maiden name). About this same time, a certain Rabbi Nathan provided the Old Testament with verse divisions.20 In 1475, the Jews of Italy began to publish printed portions of the Hebrew text, and in 1488 there appeared the beautiful Soncino edition, the first printed edition of the Hebrew Bible, to be followed in 1494 by the Brescia edition, the version which Luther was to use. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,”1968, infidels.org ]

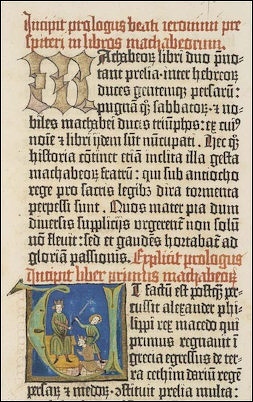

detail from the Old Testament of the Gutenberg Bible

“In this turbulent era of developing concepts, William Tyndale grew up (born 1484). After study at Oxford, Tyndale conceived the idea of translating the Bible so that, as he put it to one clergyman, "ere many years I will cause a boy that driveth the plough shall know more of the Scripture than thou doest." His efforts received little encouragement from the clergy or crown and only engendered growing hostility, which caused him to flee to Hamburg and then to Cologne so that he might work in safety. His initial translations were of the New Testament, but by 1531 he had published a rendering of the Pentateuch and Jonah based on the Hebrew text. Shortly afterward he was entrapped by his enemies. After sixteen years of imprisonment, he was brought to trial, sentenced, strangled at the stake and burned. Tyndale's determination to place the Bible in the hands of the common man was to bear more fruit. His translations became the basis of subsequent English versions.

“As Tyndale was publishing in England, translations were appearing in other languages. A new Latin version was made by Sanctes Pagninus in 1528. A German edition by Zwingli and Leo Juda was published in 1530. In 1534, Luther translated the Bible into German,21 and his work became the basis for subsequent translations in Scandanavian countries. Chanteillon made a French translation in 1551.

“It is not too surprising to find that when Miles Coverdale prepared his edition of the Bible (1535-6), he drew upon the translations of Tyndale, Luther and Zwingli-Juda. Coverdale's work was dedicated to King Henry VIII and was widely approved, for it appeared to meet the demands of both laity and clergy. For the first time, the books of the Apocrypha were printed separately.

“More English versions followed, for it had become clear that there was a thriving market for Bibles. Matthew's Bible (1537) was little more than a compilation of the work of Tyndale and Coverdale, probably prepared by John Rogers, a disciple of Tyndale. In 1539, Coverdale brought out the Great Bible, a publication of splendid proportions and form, printed in France. This Bible was authorized by King Henry VIII. The Old Testament was a revision of the Matthew (Rogers-Tyndale-Coverdale) edition.

“The English reformation encountered serious difficulties and Henry VIII took drastic action that can only be called anti-reform. In 1543, all Tyndale Bibles were proscribed, and by 1546, all Bibles except the Great Bible were outlawed. Bible burning became the order of the day. During the short reign of Edward VI, successor to Henry, Bible reading once again became legal.

“When Mary Tudor, a Roman Catholic, became Queen of England in 1553, all use of the English Bible was forbidden. English Protestant scholars fled to Switzerland and began a revision of the Great Bible. Their finished product, the Geneva Bible (1560), was dedicated to Queen Elizabeth, who was now on the throne. This Bible became the popular version of the people, but the Great Bible, revised by a committee composed largely of bishops (1563-4), was the authoritative edition for ecclesiastical purposes. The revised Great Bible was known as "The Bishops' Bible."

“The popularity of the English Bible among Protestants produced a demand by Roman Catholic laity for a version they too could read and understand. Roman Catholic refugees from England had opened an English College at Douai, France, and the official Catholic translation was begun there. Shortly afterward the seminary moved to Rheims. The New Testament was issued from Rheims in 1582. By the time the Old Testament appeared in 1609, the school had returned to Douai. The completed Bible is called the Rheims-Douai version, translated, according to the title page, from "the authentical Latin."”

King James Bible

frontpiece of a 1611 King James Bible

Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “In 1603, James I became King of England. He inherited the benefits of the Elizabethan age: the developing attitude of tolerance, the strong spirit of intellectual excitement (prompted by such men as Shakespeare, Bacon, Jonson) and broad interest in religious matters. James was something of a Bible scholar, and is said to have tried his hand at translation. In an attempt to ease some of the tensions among Christians, he responded to a suggestion of Dr. John Reynolds of Oxford, a Puritan, that a new translation of the Bible be undertaken. Forty-seven scholars and learned clergymen were appointed to the translation committee (James' letter of authorization mentions fifty-four). Among the guide rules developed for translation were the following: [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,”1968, infidels.org ]

“The Bishops' Bible was to be followed and only altered where necessary. 1) Old ecclesiastical terms were to be retained. 2) No marginal notes were to be included except to give suitable alternate readings or to cite parallel passages. 3) Wherever Tyndale, Matthew, Coverdale, the Great Bible, or the Geneva Bible, were closer to the original text, these translations were to be followed.

“The finished product, the famous King James Version of 1611, was not a perfect work, and in 1613 a revised edition appeared. As a result of sharp criticism, a third revision was made in 1629. Unfortunately, the Codex Alexandrinus had not arrived in England in time to be consulted, and eminent scholars were pressing for a new translation. The King James Version went through further revisions, one in 1638, another more extensive one in 1762 and in 1769 still another, in which spelling and punctuation were brought up to date. The Rheims-Douai version was revised in 1749 by Bishop Richard Challoner.

19th and 20th Century Revisions of the Bible

Larue wrote: “In the nineteenth century, a complete, scholarly, revision of the King James Version, utilizing codices recently available, was undertaken, and the finished product appeared in 1885 as the Revised Version. It immediately came under fire. It lacked the smoothness and beauty of the King James English, which by this time had become hallowed with age. In America, there were those who thought that too many English idioms and too many archaic words and phrases were included. An American Standard Version, a special revision of the English Revised Version, was published in 1901. The American edition had a better reception than its English counterpart, but remained second in importance to the King James Version. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,”1968, infidels.org ]

“In 1884, the first Jewish English language Bible was published in the United States. In 1917 another translation, called The Holy Scriptures According to the Massoretic Text, was published by the Jewish Publication Society. In England the noted British scholar, Dr. James Moffatt, translated the Bible into what he termed "the English of our own day" and what he hoped would be "effective, intelligible English." The New Testament appeared in 1913, the Old Testament in 1924, and the combination of the two entitled A New Translation of the Bible in 1926. Shortly afterward, in 1939, The Complete Bible: An American Translation, the work of eminent Canadian and American scholars, was published. There were four translators of the Old Testament and a single translator of the Apocrypha, each of whom was free to follow individual style in all but basic essentials. The aim was to present "the Old Testament to the modern world in its own speech" making use of the latest and best knowledge of Hebrew linguistic studies. Despite the popularity of these modern language versions, the King James version continued to be the standard text used by Protestant churches and laity, and among Christian educators there was a growing conviction that the time was at hand for a revision of the King James Bible.

“In 1937, the International Council of Religious Education, composed of representatives of forty major Protestant denominations in the United States and Canada, voted to begin a revision of the American Standard Version, which would "embody the best results of modern scholarship as to the meaning of the Scriptures, and express their meaning in English diction which is designed for use in public and private worship and preserves those qualities which have given to the King James Version a supreme place in English literature." The Revised Standard Version of the New Testament appeared in 1946. When the National Council of Churches was formed in 1950, the International Council of Religious Education was one of the merging agencies, and the Bible translation program came under National Council sponsorship. In 1952, the RSV Old Testament was published, and in 1957, the Apocrypha. Broadly speaking, the new version was enthusiastically welcomed, but criticisms by a vocal minority tended to be dogmatic and for the most part devoid of scholarship.23

“Meanwhile, numerous other translations have been published. The Confraternity of Christian Doctrine Version, a product of Roman Catholic scholarship, has appeared. A new Jewish edition has been undertaken. Scholarly translations of individual books with notes and comments appear in the Anchor Bible series.

“It is not anticipated that translations will cease. Agencies such as the American Bible Society have translated parts of the Bible into tongues ranging from Abor-Miri to Zulu, and they are still a long way from their objective of making the Bible available "to every man on earth in whatever language he may require." As the English language continues to change, new versions will become necessary, and perhaps, through the discovery of new manuscripts, troublesome passages will be explained and better readings emerge. No one version should ever be permitted to become authoritative for all time, but each translation must be measured on the basis of its faithful presentation of the best manuscripts.

Agnes and Margaret Smith: Sisters of the Sinai

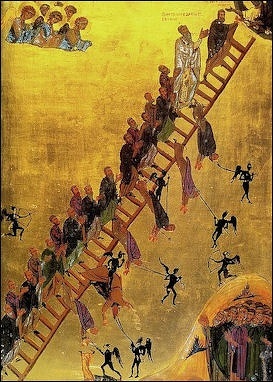

Ladder of Divine Ascent from St Catherine's

In a review of the book “Sisters of the Sinai”, Caroline Alexander wrote in the New York Times: “Despite its popular characterization as a period of stultifying stuffiness or, as the O.E.D. puts it, of “prudishness and high moral tone,” the Victorian age abounded with adventurers intent on intellectual discovery. These included the explorer Richard Burton, who brought back to mother England not only geographical information from Africa and Arabia, but also translations of Oriental erotica; and Mary Kingsley, whose travels in equatorial Africa made her an enlightened amateur scholar of African fetish beliefs; not to mention Charles Darwin, whose travels in South America rewrote the history of the world. As Janet Soskice makes clear in “The Sisters of Sinai,” figuring among the ranks of such adventurous seekers were Agnes and Margaret Smith, identical Scottish twins, whose travels to St. Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai desert resulted in the electrifying discovery of one of the oldest manuscripts of the Gospels ever found. [Source: Caroline Alexander, New York Times September 1, 2009 /*]

“The Smith sisters were born in 1843, in Irvine, Scotland, and raised with stern enlightenment by their very wealthy widowed father, who, as Soskice reports, “educated his daughters more or less as if they had been boys.” In particular, he promised his daughters that he would take them to every country whose language they learned, a pact that, given the happy combination of the twins’ love of both languages and travel, resulted in their mastery of French, German, Spanish and Italian at a young age. Unshakably devout Presbyterians throughout their lives, the twins were deeply interested in biblical studies and languages, and between them eventually acquired Hebrew, ancient and modern Greek, Arabic and old Syriac. A desire to see the land of Abraham and Moses prompted their first adventure, a trip chaperoned by a lady companion, Grace Blyth, to Egypt and the Nile. Manifesting the unflappable hardiness that would serve them well on their many future travels, the twins not only survived the duplicitous mismanagement of their dragoman, or interpreter guide, but also enjoyed their near misadventure. /*\

“Both sisters eventually made happy, if brief, marriages, Margaret to James Gibson, a Scottish minister of renowned eloquence and wide travel, and Agnes to Samuel Savage Lewis, a librarian and keeper of manuscripts at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, and a scholar of enormous energy and erudition; Lewis’s circle of learned, progressive Cambridge associates was to transform both sisters’ lives. Each marriage lasted some three years, and each ended with the abrupt and much-lamented death of a husband. It was in great part as an antidote to grief that the widowed sisters determined to fulfill a long-deferred wish to visit St. Catherine’s Monastery in the Egyptian desert, near Mount Sinai.” /*\ Book: Sisters of the Sinai by Janet Sockice, Knopf 2009

Smith Sisters Discoveries at St. Catherine’s in the Sinai

Alexander wrote in the New York Times: “Margaret Gibson and Agnes Lewis arrived in Cairo in January 1892, equipped with the usual expeditionary paraphernalia and letters of introduction, but also, more unusually, with elaborate photographic equipment. As Soskice emphasizes — and as jealous biblical scholars would pretend to forget — the twins had not stumbled into Egypt, but had come on a carefully meditated and prepared mission: to find manuscripts of interest in the legendary library of St. Catherine’s. As Soskice writes, “the latter half of the 19th century was a time of anxiety over the Bible,” an anxiety that, in an age of escalating scientific interest and discovery, pertained not only to the soundness of some of the Bible’s claims — manna from heaven, for example — but the soundness of the very text upon which believers pinned their faith. The search for earlier and better manuscripts had taken scholars into obscure corners of the globe. [Source: Caroline Alexander, New York Times September 1, 2009 /*]

“The library of St. Catherine’s, where the twins were destined, had already been searched, and even rifled, by earlier European visitors, including, most notoriously, the German scholar-adventurer Constantin von Tischendorf, who in 1859 found and “borrowed” the mid-fourth-century Codex Sinaiticus, one of the oldest and most complete manuscripts of the Bible ever found. More recently, and more significantly for the twins, J. Rendel Harris, a Quaker scholar based in Cambridge, had found in the same library an important document that gave unexpectedly early evidence of a well-developed system of Christian belief datable to the second century A.D. When Harris learned, through a chance encounter, of the twins’ plans to visit Sinai, he hastened over to meet them — and to share a secret: in a small, dark closet off a chamber beneath the archbishop’s rooms were chests of Syriac manuscripts that he had been unable to examine. /::\

When, then, Agnes and Margaret arrived at St. Catherine’s, having traveled nine days by camel through the desert, they were specifically intent on examining the contents of this closet. At Harris’s suggestion, they had also come prepared to photograph manuscript finds they would not have the opportunity to transcribe on site — preparations that give evidence of both their seriousness of purpose and their expectations of success. And successful they were. Handling a dirty wad of vellum, sharp-eyed Agnes saw that its text, a racy collection of the lives of female saints, was written over another document. When close scrutiny revealed the words “of Matthew,” and “of Luke,” she realized she was holding a palimpsest containing the Gospels. Written in Syriac, a dialect of the Aramaic Jesus had spoken, the Sinai Palimpsest, or Lewis Codex, as it came to be called, would prove to date to the late fourth century; the translation it preserved was even older, dating from the late second century A.D. — “very near the fountainhead” of early Christianity.

Soskice follows the aftershocks of this extraordinary discovery as they reverberate both through the twins’ lives and through the world of biblical scholarship; among other things, the new codex’s Book of Mark lacked the final verses describing Christ’s Resurrection.

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons except Bible Development Time, Relevancy 22, and canon list, Bible diagrams

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, King James Version of the Bible, gutenberg.org, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com Complete Works of Josephus at Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL), translated by William Whiston, ccel.org , Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994); National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated February 2024