Home | Category: Life, Families, Women

MESOPOTAMIAN SOCIETY

As urban life developed, society became more complex. In the past people lived around villages or farms and grew little more food than they could consume themselves and traded very little partly because there was nobody to trade to. As populations became large and more centralized, there was more people to trade to. Thus there was an incentive for farmers to produce surpluses and sell them and tradesmen to produce other goods to trade with them.

Mesopotamians are regarded as the first people to develop a wealthy class. Craftsmen made up what would qualify as a middle class. As society became more complex there were different trades and the interrelation between them became more complex too. See Labor.

The Sumerians, Babylonian and Assyrians all had slaves. Early slaves were perhaps captives of war. The most famous slaves were the Jews captured under King Nebuchadnezzar. Slaves were bought and sold in the market. They worked in irrigation projects, temples and palaces. In the Babylonian period, enslavement for debt was illegal.

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Society and the Individual in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Laura Culbertson, Gonzalo Rubio (2024) Amazon.com;

“Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History” by Nicholas Postgate (1994) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamia” (Case Studies in Early Societies, Series Number 1)

by Susan Pollock (1999) Amazon.com;

“Economy and Society of Ancient” Mesopotamia (Studies in Ancient Near Eastern Records) by Steven Garfinkle and Gonzalo Rubio (2025) Amazon.com;

“Law Collections from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor” by Martha T. Roth (1997) Amazon.com;

“Sin and Sanction in Israel and Mesopotamia: A Comparative Study” by K Van Der Toorn (1985) Amazon.com;

“Wisdom Literature in Mesopotamia and Israel” (Society of Biblical Literature Symposium)

by Richard J. Clifford (2007) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Stephen Bertman (2002) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamia: Life in the Cradle of Civilization” by Amanda H Podany (2018) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Karen Rhea Nemet-Nejat (1998) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Babylon and Assyria” by Georges Contenau (1954) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian World” by Gwendolyn Leick (2007) Amazon.com;

“Neo-Babylonian Letters and Contracts from the Eanna Archive” (Yale Oriental Series: Cuneiform Texts) by Eckart Frahm and Michael Jursa (2011) Amazon.com;

Three Classes of Babylonian Society

By the time the Babylonians were dominate there were three distinct classes: 1) nobles with hereditary estates; 2) freemen, who could own land but not pass it on to their children; and 3) slaves.

Claude Hermann and Walter Johns wrote in the Encyclopedia Britannica: The Hammurbai “Code contemplates the whole population as falling into three classes, the amelu, the muskinu and the ardu. The amelu was a patrician, the man of family, whose birth, marriage and death were registered, of ancestral estates and full civil rights. He had aristocratic privileges and responsibilities, the right to exact retaliation for corporal injuries, and liability to heavier punishment for crimes and misdemeanours, higher fees and fines to pay. To this class belonged the king and court, the higher officials, the professions and craftsmen. The term became in time a mere courtesy title but originally carried with it standing. [Source: Claude Hermann Walter Johns, Babylonian Law — The Code of Hammurabi. Eleventh Edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, 1910-1911 ]

“Already in the Code, when status is not concerned, it is used to denote "any one." There was no property qualification nor does the term appear to be racial. It is most difficult to characterize the muskinu exactly. The term came in time to mean "a beggar" and with that meaning has passed through Aramaic and Hebrew into many modern languages; but though the Code does not regard him as necessarily poor, he may have been landless. He was free, but had to accept monetary compensation for corporal injuries, paid smaller fees and fines, even paid less offerings to the gods. He inhabited a separate quarter of the city. There is no reason to regard him as specially connected with the court, as a royal pensioner, nor as forming the bulk of the population. The rarity of any reference to him in contemporary documents makes further specification conjectural.

“The ardu was a slave, his master's chattel, and formed a very numerous class. He could acquire property and even hold other slaves. His master clothed and fed him, paid his doctor's fees, but took all compensation paid for injury done to him. His master usually found him a slave-girl as wife (the children were then born slaves), often set him up in a house (with farm or business) and simply took an annual rent of him. Otherwise he might marry a freewoman (the children were then free), who might bring him a dower which his master could not touch, and at his death one-half of his property passed to his master as his heir. He could acquire his freedom by purchase from his master, or might be freed and dedicated to a temple, or even adopted, when he became an amelu and not a muskinu. Slaves were recruited by purchase abroad, from captives taken in war and by freemen degraded for debt or crime.

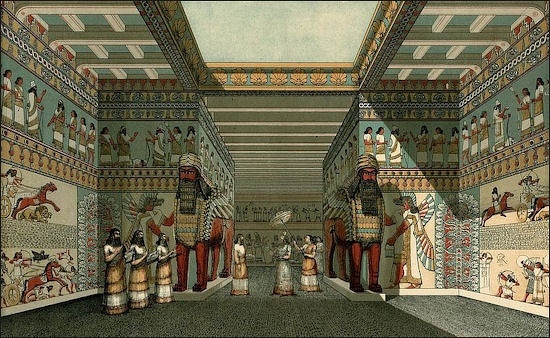

In both Babylonia and Assyria there was an aristocracy of birth based originally on the possession of land. But in Babylonia it tended at an early period to be absorbed by the mercantile and priestly classes, and in later days it is difficult to find traces even of its existence. The nobles of the age of Nebuchadnezzar were either wealthy trading families or officers of the Crown. The temples, and the priests who lived upon their revenues, had swallowed up a considerable part of the landed and other property of the country, which had thus become what in modern Turkey would be called wakf. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

In Assyria many of the great princes of the realm still belonged to the old feudal aristocracy, but here again the tendency was to replace them by a bureaucracy which owed its position and authority to the direct favor of the King. Under Tiglath-pileser III. this tendency became part of the policy of the government; the older aristocracy disappeared, and instead of it we find military officers and civil officials, all of whom were appointed by the Crown.

Ethics in Mesopotamia

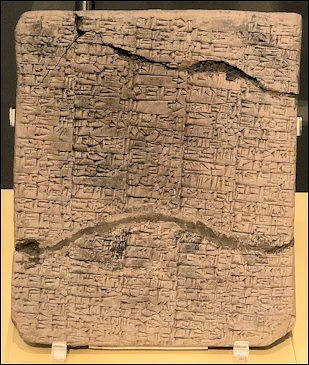

Babylonian administrative text

Morris Jastrow said: “Ethical idealism, by which is here meant a high sense of duty and a noble view of life, is possible only—so it would seem—under two conditions, either through a strong conviction that there is a compensation elsewhere for the wrongs, the injustice, and the suffering in this world, or through an equally strong conviction that the unknown goal toward which mankind is striving can be reached only by the moral growth and ultimate perfection of the human race— whatever the future may have in store. The ethics of the Babylonians and Assyrians did not look beyond this world, and their standards were adapted to present needs and not to future possibilities. The thought of the gloomy Aralu in store for all coloured their view of life,—not indeed in leading them to take a pessimistic attitude towards life, or in regarding this world as a vale of tears, but in limiting their ethical ideals to what was essential to their material well-being and mundane happiness. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“It would be an error, however, to infer that such a view of life is incompatible with relatively high standards of conduct. That is far from being the case—at least in Babylonia and Assyria. Even though the highest purpose in life was to secure as much joy and happiness as possible, the conviction was deeply ingrained, particularly in the minds of the Babylonians, that the gods demanded adherence to moral standards. We have had illustrations of these standards in the incantation texts, where by the side of ritualistic errors we find the priests suggesting the possibility that misfortune has been sent in consequence of moral transgressions—such as lying, stealing, defrauding, maliciousness, adultery, coveting the possessions of others, unworthy ambitions, injurious teachings, and other misdemeanours. The gods were prone to punish misdoings quite as severely as neglect of their worship, or indifference to the niceties of ritualistic observances.

“The consciousness of sinful inclinations and of guilt, though only brought home to men when misfortunes came or were impending, was strong enough to create rules of conduct in public and private affairs that rested on sound principles. The rights of individuals were safeguarded by laws that strove to prevent the strong from taking undue advantage of the weak. Business was carried on under the protection of laws and regulations that impress one as remarkably equitable. Underhand practices were severely punished, and contracts had to be faithfully executed. All this, it may be suggested, was dictated by the necessities of the growth of a complicated social organisation.”

Equity and the Use of Contracts in Mesopotamia

Morris Jastrow said: “True, but what is noticeable in the thousands of business documents now at our behoof and covering almost all periods from the earliest to the latest, is the spirit of justice and equity that pervades the endeavour to regulate the social relations in Babylonia and Assyria. This is particularly apparent in the legal decisions handed down by the judges, of which we have many specimens. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“As a protection to both parties engaging in business transactions, a formal contract wherein the details were noted was drawn up, and sealed in the presence of witnesses. This method was extended from loans and sales to marriage agreements, to testaments, to contracts for work, to rents, and even to such incidents as engaging teachers, and to apprenticeship. The general principle, already implied in the Hammurabi Code, and apparently in force at all periods, was that no agreement of any kind was valid without a duly attested written record. The religious element enters into these business transactions in the oath taken in the name of the gods, with the frequent addition of the name of the reigning king by both parties as a guarantee of good faith. In some cases the oath is, in fact, prescribed by law.

“If a dispute arose in regard to the terms of a contract, and no agreement could be reached by the contracting parties, the case was brought before the court, which appears to have been ordinarily composed of three judges, as among the Jews (whose method of legal procedure was largely modelled upon Babylonian prototypes). All the documents in the case had to be brought into court, and each party was obliged to bring witnesses to support any claims lying outside the record. The impression that one receives from a study of these decisions is that they were rendered after a careful and impartial consideration of the documents, and of the statements of the parties and of previous decisions.

How the Justice System Worked in Mesopotamia

Morris Jastrow said: ““An example taken from the neo-Babylonian period will illustrate the spirit by which the judges were actuated in deciding the complicated cases that were frequently brought before them. It is the case of a widow Bunanit, who brings suit to recover property, devised to her by her husband, which has been claimed by her brother-in-law. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“Her case is stated in detail: “Bunanit, the daughter of Kharisa, declared before the judges of Nabonnedos, king of Babylon, as follows: “Apil-addunadin, son of Nikbadu,” took me to wife, receiving three and a half manas of silver as my dowry, and one daughter I bore him. I and Apil-addunadin, my husband, carried on business with the money of my dowry, and bought eight GI of an estate in the Akhula-galla quarter of Borsippa, for nine and two thirds manas of silver, besides two and a half manas of silver which was a loan from Iddin-Marduk, son of Ikischa-aplu, son of Nur-Sin, which we added to the price of said estate and bought it in common.

““In the fourth year of Nabonnedos, king of Babylon, I put in a claim for my dowry against my husband Apil-addunadin, and of his own accord he sealed over to me the eight GI of said estate in Borsippa and transferred it to me for all time, and declared on my tablet as follows:‘21/2manas of silver which Apil-addunadin and Bunanit borrowed from Iddin-Marduk and turned over to the price of said estate they held in common, That tablet he sealed and wrote the curse of the gods on it.’

““In the fifth year of Nabonnedos, king of Babylon, I and my husband Apil-addunadin adopted Apil-adduamara as son, and made out the deed of adoption, stipulating two manas and ten shekels of silver and a house-outfit as the dowry of Nubta, my daughter. My husband died, and now A?abi-ilu, son of my father-in-law, has put in a claim for said estate and all that has been sealed and transferred to me, including Nebo-nur-ili whom we obtained from Nebo-akh-iddin. Before you I bring the matter. Render a decision.”

Reaching a Legal Decision in Mesopotamia

Morris Jastrow said: ““The case has been stated with great clearness. The legal point involved, because of which the brother-in-law puts in a claim on behalf of the deceased husband’s family, turns on the question whether the wife is entitled to the entire estate, seeing that her original dowry was only three and one half manas, or, in other words, whether the husband had a right to turn over to her the whole property on the ground that it was her dowry which, through business transactions conducted in common, had increased to nine and two thirds manas. Bunanit, in stating her case, lays great stress, it will be observed, on the circumstance that she and her husband did all things in common —bartered in common, bought in common, borrowed in common, adopted a son in common, and acquired a slave in common. The decision rendered by the judges is remarkably just, manifesting a due regard for the ethics of the situation, and based on an examination of the various documents or tablets in the case and which in such an instance had to be produced. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“The document continues as follows: “The judges heard their complaints, and read the tablets and contracts which Bunanit had laid before them. To A?abi-ilu they grant nothing of the estate in Borsippa, which in lieu of her dowry had been transferred to Bunanit, nor Nebo-nftr-ili, whom she and her husband had bought, nor any of the property of Apil-addunadin. They confirmed the documents of Bunanit and Apil-adduamara. The sum of two and one half manas of silver is to be returned forthwith to Iddin-Marduk who had advanced it for the sale of the house. Then Bunanit is to receive three and one half manas of silver—her dowry—and a share of the estate. Nebo-nur-ili is given to Nubta in accordance with the agreement of her father. The names of the six judges through whom the said decision was rendered are then given, followed by the names of two scribes and the date Babylon, 26th of Ulul (6th month), 9th year of Nabonnedos, king of Babylon.”

“The balance of the estate evidently passed over to the adopted son. Bunanit won her case against her brother-in-law, but it looks on the surface as though she had not won all that she had claimed. The judges practically ignored the transfer of the entire estate to her, for they granted her merely her dowry and the share of her husband’s property to which as widow she was entitled. Had there not been an adopted son, the claim of A?abi-ilu would probably have been upheld for the balance of the estate, exclusive of the slave. Bunanit is obliged to confess that her husband transferred the property “of his own accord,” which means that it was not upon an order of the court, and therefore not legally-established. It is safe to assume that the court would not have regarded such a transaction as legal, for despite the fact that the pair do not adopt a son until after the transfer, the judges allowed the widow her dowry only and her share of the estate. On the other hand, though it might appear that, as a partner, Bunanit would only have been responsible for one half of the amount borrowed from Iddin-Marduk, the judges, by ignoring the transfer, could order that Iddin-Marduk must be paid in full out of the property left by Apil-addunadin.”

Ethics of Rulers and Leadership in Mesopotamia

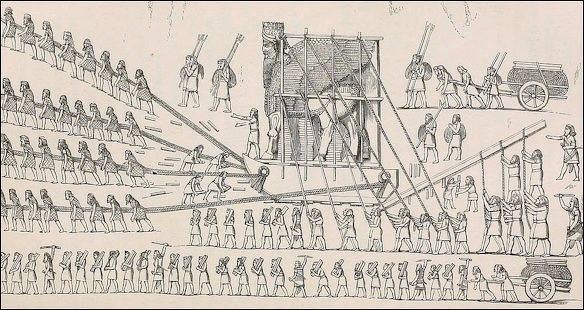

Morris Jastrow said: “The kings themselves, although not actuated, perhaps, by the highest motives, set the example of obedience to laws that involved the recognition of the rights of others. From a most ancient period there is come down to us a remarkable monument recording the conveyance of large tracts of land in northern Babylonia to a king of Kish, Manishtusu, (ca . 2700 B.C.), on which hundreds of names are recorded from whom the land was purchased, with specific descriptions of the tracts belonging to each one, as well as the conditions of sale. The king here appears with rights no more exclusive or predominant than those of a private citizen. Not only does he give full compensation to each owner, but undertakes to find occupation and means of support for fifteen hundred and sixty-four labourers and eighty-seven overseers, who had been affected by the transfer. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“The numerous boundary stones that are come down to us (recording sales of fields or granting privileges), which were set up as memorials of transactions, are silent but eloquent witnesses to the respect for private property. The inscriptions on these stones conclude with dire curses in the names of the gods against those who should set up false claims, or who should alter the wording of the agreement, or in any way interfere with the terms thereon recorded. The symbols of the gods were engraved on these boundary stones as a precaution and a protection to those whose rights and privileges the stone recorded. The Babylonians could well re-echo the denunciations of the Hebrew prophets against those who removed the boundaries of their neighbours’ fields. Even those Assyrian monarchs most given to conquest and plunder boast, in their annals, of having restored property to the rightful owners, and of having respected the privileges of their subjects and dependents.

“For instance, Sargon of Assyria (721-705 B.C.), while parading his conquests in vain-glorious terms, and proclaiming his unrivalled prowess, emphasises the fact that he maintained the privileges of the great centres of the south, Sippar, Nippur, and Babylon, and that he protected the weak and righted their injuries. His successor Sennacherib claims to be the guardian of justice and a lover of righteousness. Yet, these are the very same monarchs who treated their enemies with unspeakable cruelty, inflicting tortures on prisoners, violating women, mutilating corpses, burning and pillaging towns.

“More significant still is the attitude of a monarch like Hammurabi, who, in the prologue and epilogue to his famous Code, refers to himself as a “king of righteousness,” actuated by a lofty desire to protect the weak, the widow, and the orphan. In setting up copies of this Code in the important centres of his realm, his hope is that all may realise that he, Hammurabi , tried to be a “father” to his people. He calls upon all who have a just cause to bring it before the courts, and gives them the assurance that justice will be dispensed,—all this as early as nigh four thousand years ago!

“On a tablet commemorative of the privileges accorded to Sippar, Nippur, and Babylon—to which, we have just seen, Sargon refers in his annals—there are grouped together, in the introduction, a series of warnings, which may be taken as general illustrations of the principles by which rulers were supposed to be guided:

If the king does not heed the law, his people will be destroyed; his power will pass away.

If he does not heed the law of his land, Ea, the king of destinies, will judge his fate and cast him to one side.

If he does not heed his abkallu, his days will be shortened.

If he does not heed the priestess, his land will rebel against him.

If he gives heed to the wicked, confusion will set in.

If he gives heed to the counsels of Ea, the great gods will aid him in righteous decrees and decisions.

If he oppresses a man of Sippar and perverts justice, Shamash, the judge of heaven and earth, will annul the law in his land, so that there will be neither abkallu nor judge to render justice.

If the Nippurians are brought before him for judgment, and he oppresses them with a heavy hand, Enlil, the lord of lands, will cause him to be dispatched by a foe and his army to be overthrown; chief and general will be humiliated and driven off.

If he causes the treasury of the Babylonians to be entered for looting, if he annuls and reverses the suits of the Babylonians, then Marduk, the lord of heaven and earth, will bring his enemy against him, and will turn over to his enemy his property and possessions.

If he unjustly orders a man of Nippur, Sippar, or Babylon to be cast into prison, the city where the injustice has been done, will be made desolate, and a strong enemy will invade the prison into which he has been cast.

“In this strain the text proceeds; and while the reference is limited to the three cities, the obligations imposed upon the rulers to respect privileges once granted may be taken as a general indication of the standards everywhere prevailing. We must not fail, however, to recognise the limitation of the ethical spirit, manifest in the threatened punishments, should the ruler fail to act according to the dictates of justice and right. For all this, whether it was from fear of punishment, or desire to secure the favour of the gods, the example of their rulers in following the paths of equity and in avoiding tyranny and oppression must have reacted on their subjects, and incited them to conform their lives to equally high standards.

Moral Precepts in Mesopotamia

Morris Jastrow said: “There is extant a text—unfortunately preserved only in part—which, somewhat after the manner of the Biblical “Book of Proverbs,” lays down certain moral precepts that were intended to be of general application. That it is a fragment, and an Assyrian copy of an older text, suggests an inference that there may have been similar and even more extensive collections; and, perhaps, some fortunate chance will bring to light more texts among the archives of Babylonian temples, from which the texts of Ashur-banapal’s library were for the most part copied. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“The fragment, which may be taken as a fair example of the ethical teachings prescribed by the priests, reads as follows:

“Thou shalt not slander—speak what is pure!

Thou shalt not speak evil—speak kindly!

He who slanders (and) speaks evil,

Shamash will visit recompense on his head.

Let not thy mouth boast—guard thy lip!

When thou art angry, do not speak at once!

If thou speakest in anger, thou wilt repent afterwards,

And in silence sadden thy mind.

Daily approach thy god,

With offering and prayer as an excellent incense!

Before thy god (come) with a pure heart,

For that is proper towards the deity!

Prayer, petition, and prostration,

Early in the morning shalt thou render him;

And with god’s help, thou wilt prosper.

In thy wisdom learn from the tablet.

The fear (of god) begets favour,

Offering enriches life,

And prayer brings forgiveness of sin.

He who fears the gods, will not cry [in vain].

He who fears the Anunnaki, will lengthen [his days].

With friend and companion thou shalt not speak [evil ].

Thou shalt not say low things, but (speak) kindness.

If thou promisest, give [what thou hast promised ].

Thou shalt not in tyranny oppress them,

For this his god will be angry with him;

It is not pleasing to Shamash—he will requite him with evil.

Give food to eat, wine to drink.

Seek what is right, avoid [what is wrong ].

For this is pleasing to his god;

It is pleasing to Shamash—he will requite him [with mercy].

Be helpful, be kind [to the servant].

The maid in the house thou shalt [protect ].

“Brief as the fragment is, it covers a large proportion of the relations of social life. The advice given is largely practical, and the reward offered is ever of this world—long life, happiness, freedom from misfortune—while errors, be they moral or ritualistic, bring their own punishment with them. The ethics taught is not of a kind to carry us upward into higher regions, and the nearest approach to a nobler touch is in the inculcation of the proper attitude toward the gods, and of kindness and mercy toward fellow-men; but in spite of these obvious limitations, the ethical standards in the precepts show that it was considered, at least, the part of wisdom to maintain a clean morality. Worldly wisdom takes the precedence throughout in popular maxims and sayings, and it is from this point of view that we must consider such a text as the present one. Wholesome teachings, even where the motives enjoined are not of the highest, may yet point to sound moral foundations and indicate that the ethical sense has had its awakening. A nobler height may be gained in course of time.”

Hammurabi’s Code and Ethics in Mesopotamia

Morris Jastrow said: “The spirit of Hammurabi’s Code further illustrates the ethical standards imposed alike upon rulers, priests, and people. The business and legal documents of Babylonia and Assyria show that the laws, codified by the king, and representing the summary of legal procedures and legal decisions down to his day, were not only enforced but interpreted to the very letter. To be sure, the Code embodies side by side enactments of older and later dates. It contains examples of punishment by ordeal, as, e.g., in the case of a culprit accused of witchcraft, where the decision is relegated to the god of the stream into which the defendant is cast. If the god of the stream takes him unto himself, his guilt is established. If the god by saving him declares his innocence, the plaintiff is put to death and his property forfeited for the benefit of the defendant, wrongfully accused. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

Hammurabi Code

“The lex talionis —providing “eye for eye, bone for bone, and tooth for tooth”—also finds a place in the Code; but in both the ordeal and in the lex talionis, it does not differ from the Pentateuchal Codes, which, likewise compilations of earlier and later decrees, prescribe the ordeal in the case for instance of the woman accused of adultery; and if it be maintained that the principle of “eye for eye and tooth for tooth” is set up in the Old Testament merely as a basis for a compensation equal to the injury done, the same might hold good for the Ham-murapi Code and with even greater justification, since the Code actually limits the lex talionis to the case of an injury done to one of equal rank, while in the case of one of inferior or superior rank, a fine is imposed, which suggests that the lex talionis as applied to one of equal rank has become merely a legal phrase to indicate that a return, equal to the value of an eye or a tooth to him who suffers the assault, is to be imposed.

“This, of course, is a mere supposition, but at all events the underlying principle is one of equal compensation, and in so far it is ethical in its nature. On the other hand, there can be no doubt that the original import of the lex talionis , among both Babylonians and Assyrians (as among the Hebrews), involved a literal interpretation, as may be concluded from the particularly harsh and inconsequent application to the case of the son of a builder, who is to be put to death should an edifice, erected by his father, fall and kill the son of the owner.

Intention and Neglect in the Hammurabi Code

Claude Hermann and Walter Johns wrote in the Encyclopedia Britannica:“The Code recognized the importance of intention. A man who killed another in a quarrel must swear he did not do so intentionally, and was then only fined according to the rank of the deceased. The Code does not say what would be the penalty of murder, but death is so often awarded where death is caused that we can hardly doubt that the murderer was put to death. If the assault only led to injury and was unintentional, the assailant in a quarrel had to pay the doctor's fees. [Source: Claude Hermann Walter Johns, Babylonian Law — The Code of Hammurabi. Eleventh Edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, 1910-1911 ]

“A brander, induced to remove a slave's identification mark, could swear to his ignorance and was free. The owner of an ox which gored a man on the street was only responsible for damages if, the ox was known by him to be vicious, even if it caused death. If the mancipium died a natural death under the creditor's hand, the creditor was scot free. In ordinary cases responsibility was not demanded for accident or for more than proper care. Poverty excused bigamy on the part of a deserted wife.

“On the other hand carelessness and neglect were severely punished, as in the case of the unskilful physician, if it led to loss of life or limb his hands were cut off, a slave had to be replaced, the loss of his eye paid for to half his value; a veterinary surgeon who caused the death of an ox or ass paid quarter value; a builder, whose careless workmanship caused death, lost his life or paid for it by the death of his child, replaced slave or goods, and in any case had to rebuild the house or make good any damages due to defective building and repair the defect as well. The boat-builder had to make good any defect of construction or damage due to it for a year's warranty.”

Punishments in Hammurabi’s Code

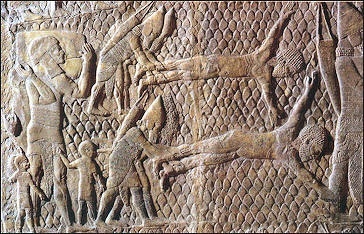

Assyrians flaying rebels

Morris Jastrow said: ““Another unfavourable feature of the Code...lies in the extreme severity of many of its punishments. The penalty of death is imposed for about fifty offences, some of them comparatively trivial, such as stealing temple or royal property, where, however, the element of sacrilege enters into consideration. Even the claimant of a property, alleged to have been purchased from a man’s son or servant, or of a member of the higher class, who is unable to show the contract, is held to be a thief, because of the fraudulent intent, and is put to death [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

The law is, however, fair in its application, and punishes with equal severity, when there is a fraudulent attempt to deprive one of legally acquired property. He who aids a runaway slave is placed in the same category as he who steals a minor son, or as he who conspires to take property away from his neighbour, and is put to death for the fraudulent attempt. A plunderer at a fire is himself thrown into that fire, and he who has broken into a man’s house is immured in the breach that he himself has made.

“In cases of assault and battery, a distinction is drawn according to the rank of the assailant and the assailed. If a person of lower rank attacks a person of higher rank, the punishment is a public whipping of sixty lashes with a leather thong, whereas if the one attacked is of equal rank, the whipping is remitted, but a heavy fine— one mana of silver—is imposed. If a slave commits this offence, and the victim is of high rank, the slave’s ear is cut off At the same time, an ethical spirit is revealed in the stipulation that, if the injury be inflicted in a chance-medley, and the blow not intentionally aimed at any particular person, the offender is discharged with the obligation to pay the doctor’s bill, or, in the event of the death of the victim, with a fine according to the rank of the deceased. A lower level of equity is, however, represented by the enactments that, in case a man shrikes a pregnant woman and the woman dies, a daughter of the offender is put to death, or in case a surgical operation on the eye is not successful, and the patient loses his eye, the surgeon’s hand is to be cut off, or in the event of the death of a slave under an operation, the surgeon must reimburse the owner by giving him another slave.

Proverbs from Ki-en-gir (Sumer)

Proverbs from Ki-en-gir (Sumer), c. 2000 B.C.

1. Whoever has walked with truth generates life.

2. Do not cut off the neck of that which has had its neck cut off.

3. That which is given in submission becomes a medium of defiance.

4. The destruction is from his own personal god; he knows no savior.

5. Wealth is hard to come by, but poverty is always at hand.

6. He acquires many things, he must keep close watch over them.

7. A boat bent on honest pursuits sailed downstream with the wind; Utu has sought out honest ports for it.

8. He who drinks too much beer must drink water.

9. He who eats too much will not be able to sleep. [Source: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia]

- Since my wife is at the outdoor shrine, and furthermore since my mother is at the river, I shall die of hunger, he says.

11. May the goddess Inanna cause a hot-limited wife to lie down for you; May she bestow upon you broad-armed sons; May she seek out for you a place of Happiness.

12. The fox could not build his own house, and so he came to the house of his friend as a conqueror.

13. The fox, having urinated into the sea, said AThe whole of the sea is my urine.@

14. The poor man nibbles at his silver.

15. The poor are the silent ones of the land.

16. All the households of the poor are not equally submissive.

17. A poor man does not strike his son a single blow; he treasures him forever.

ùkur-re a-na-àm mu-un-tur-re

é-na4-kín-na gú-im-šu-rin-na-kam

túg-bir7-a-ni nu-kal-la-ge-[da]m

níg-ú-gu-dé-a-ni nu-kin-kin-d[a]m

[How lowly is the poor man!

A mill (for him) (is) the edge of the oven;

His ripped garment will not be mended;

What he has lost will not be sought for! poor man how-is lowly

mill edge-oven-of

garment-ripped-his not-excellent-will be

what-lost-his not-search for-will be [Source: Sumerian.org]

ùkur-re ur5-ra-àm al-t[u]r-[r]e

ka-ta-kar-ra ur5-ra ab-su-su

The poor man — by (his) debts is he brought low!

What is snatched out of his mouth must repay (his) debts. poor man debts-is thematic particle-made small

mouth-from-snatch debts thematic particle-repay

níg]-ge-na-da a-ba in-da-di nam-ti ì-ù-tu Whoever has walked with truth generates life. truth-with whoever walked life generates

Ahikar the Wise: His Legend and Proverbs

Ahikar and the Celestial Town

The story of Ahikar (Ahiqar) the Wise is one of the most popular and often translated in the ancient Middle East. While it is thought that the original was written in Assyrian language, the story exists in many versions. These include Syriac, Arabic, Armenian, Slavonic, Georgian, Old Turkish, Romanian, Russian, Serbian, and English. The story of Ahikar is made up of two parts. The first part is the story of Ahikar, a wise and respected official of the Assyrian Empire. As he grows old. Ahikar becomes upset by the fact that he has no son to pass his wisdom onto. As time goes on, and all else fails, he decides to adopt his nephew Nadan and instruct him to take his place at court. Nadan, however, turns out to be disloyal and plots against his uncle. Eventually, Nadan is found out and punished. Within the framework of this story. Ahikar has two opportunities to instruct Nadan in the wisdom he has acquired. Here is the second part of the story which is made of series of proverbs, and wise sayings. Scholars agree that there is a true historical basis to Ahikar and his proverbs. An Assyrian tablet from the Seleucid era relates that " In the time of king Esarhaddon, Aba-enlil-dari whom the Arameans call Ahikar was ummanu (court scholar). [Source: Internet Archive]

Selected Proverbs of Ahikar The Wise:

1. Hear, O my son Nadan, and come to the understanding of me, and be mindful of my words, as the words of God.

2. My son Nadan, if thou hast heard a word, let it die in thy heart, and reveal it to no man; lest it become a hot coal in thy mouth and burn thee, and thou lay a blemish on thy soul, and be angered against God.

3. My son, do not tell all that thou hearest, and do not disclose all that thou seest.

4. My son, do not loose a knot that is sealed, and do not seal one that is loosed.

Televison 5. My son, commit not adultery with the wife of thy neighbor; lest others should commit adultery with thy wife.

6. My son, be not in a hurry, like the almond tree whose blossom is the first to appear, but whose fruit is the last to be eaten; but be equal and sensible, like the mulberry tree whose blossom is the last to appear, but whose fruit is the first to be eaten.

My son, it is better to remove stones with a wise man that to drink wine with a fool.

8. My son, with a wise man thou wilt not be depraved, and with a depraved man thou wilt not become wise.

9. My son, the rich man eats a snake, and they say, he ate it for medicine. And the poor man eats it, and they say, for his hunger he ate it.

10 My son, if thine enemy meet thee with evil, meet thou him with wisdom.

11. My son, walk not in the way unarmed; because thou knowest not when thy enemy shall come upon thee.

12. My son, let thy words be true, in order that thy lord may say to thee, 'Draw near me,' and thou shalt live.

13. My son, lie not in thy speech before thy lord, lest thou be convicted, and he shall say to thee, 'Away from my sight!'My son, smite with stones the dog that has left his own master and followed after thee.

15. My son, the flock that makes many tracks becomes the portion of the wolves.

16. My son, test thy son with bread and water, and then thou canst leave in his hands thy possessions and thy wealth.

17. My son, I have carried iron and removed stones; and they were not heavier on me than a man who settles in the house of his father-in-law.

18. My son, I have carried salt and removed lead; and I have not seen anything heavier than that a man should pay back a debt which he did not borrow.

19. My son, better is he that is blind of eye than he that is blind of heart; for the blind of eye straightway learneth the road and walketh in it: but the blind of heart leaveth the right way and goeth into the desert.

20. My son, let not a word go forth from thy mouth until thou hast taken counsel within thy heart: because it is better for a man to stumble in his heart than to stumble with his tongue.

21. My son, put not a gold ring on thy finger, when thou hast not wealth [ or ' when it is not thine. ']; lest fools make mock of thee.

Advice To an Assyrian Prince

The following text is written on a tablet from the libraries of Assurbanipal, and no duplicate copy has yet been found:

1. If a king does not heed justice, his people will be thrown into chaos and his land will be devastated.

2. If he does not heed the justice of his land, Ea, king of destinies,

3. Will alter his destiny and he will not cease from hostilely pursuing him.

4. If he does not heed his nobles, his life will be cut short.

5. If he doe snot heed his adviser, his land will rebel against him.

6. If he heeds a rogue, the status quo in his land will change.

7. If he heeds a trick of Ea, the great gods.

8. In unison and in their just ways will not cease from prosecuting him.

9. If he improperly convicts a citizen of Sippar, but acquits a foreigner, Shamash, judge of heaven and earth,

10. Will set up a foreign justice in his land, where the princes and judges will not heed justice

11. If citizens of Nippur are brought to him for judgement, but he accepts a present and improperly convicts them

12. Enlil, lord of the lands, wil bring a foreign army against him

13. to slaughter his army,

14. whose prince and chief officers will roam his streets like fighting-cocks

[Source: Lambert, W. G. Babylonian Wisdom Literature. From the Oxford University Press edition published in 1963, reprinted in 1996 by Eisenbrauns. piney.com]

.

15. If he takes silver of the citizens of Babylon and adds it to his own coffers,

16. Of if he hears a lawsuit involving men of Babylon but treats it frivolously,

17. Marduk, lord of Heaven and earth, will set his foes upon him,

18. And will give his property and wealth to his enemy.

19. If he imposes a fine on the citizens of Nippur, Sippar or Babylon,

20. Of if he puts them in prison,

21. The city where the fine was imposed will be completely overturned,

22. And a foreign enemy will make his way into the prison in which they were put.

23. If he mobilized the whole of Sippar, Nippur and Babylon,

24. And imposed forced labour on the people,

25. Exacting from them a corvée at the herald´s proclamation,

26. Marduk, the sage of the gods, the prince, the counsellor,

27. Will turn his land over to his enemy

28. So that the troops of his land will do forced labour for his enemy,

29. For Anu, Enlil and Ea, the great gods,

30. Who dwell in heaven and earth, in their assembly affirmed the freedom of those people from such obligations.

31, 32. If he gives the fodder of the citizens of Sippar, Nippur and Babylon to his own steeds,

33. The steeds who eat the fodder

34. Will be led away to the enemy´s yoke,

35. And those men will be mobilized with the king´s men when the national army is conscripted.

36. Mighty Erra, who goes before his army,

37. Will shatter his front line and go at this enemy´s side.

38. If he looses the yokes of their oxen,

39. And puts them into other fields

40. Or gives them to a foreigner, [...] will be devastated [...] of Addu.

41. If he seizes their ... stock of sheep,

42. Addu, canal supervisor of heaven and earth,

43. Will extirpate his pasturing animals by hinger

44. And will amass offerings for Shamash.

45. If the adviser or chief officer of the king´s presence

46. Denounces them (i.e. the citizens of Sippar, Nippur and Babylon) and so obtains bribes from them,

47. At the command of Ea, king of the Apzu,

48. The adviser chief officer will die by the sword,

49. Their place will be covered over as a run,

50. The wind will carry away their remains and their achievements will be given over to the storm wind.

- If he declares their treaties void, or alters their inscribed treaty stele,

52. Sends them on a campaign or press-gangs them into hard labour,

53. Nabu, scribe of Esagila, who organizes the whole of heaven and eath, who directs everyting,

54. Who ordains kingship, will declare the treaties of his land void , and will decree hostility.

55. If either a shepherd or a temple overseer, or a chief officer of the king,

56. Who serves as a temple overseer of Sippar, Nippur or Babylon

57. Imposes forced labour on them (i.e. the citizens of Sippar, Nippur and Babylon) in connection with the temples of the great gods,

58. The great gods will quit their dwelling i their fury and

59. Will not enter their shrines.

Babylonian Proverbs from Ashurbanipal's Library

Synonym list from Ashurbanipal's library

Some Babylonian Proverbs from the Library of Ashurbanipal

1. A hostile act thou shalt not perform, that fear of vengeance shall not consume you.

2. You shalt not do evil, that life eternal you may obtain.

3. Does a woman conceive when a virgin, or grow great without eating?

4. If I put anything down it is snatched away; if I do more than is expected, who will repay me?

5 He has dug a well where no water is, he has raised a husk without kernel.

6. Does a marsh receive the price of its reeds, or fields the price of their vegetation?

7. The strong live by their own wages; the weak by the wages of their children.

8. He is altogether good, but he is clothed with darkness.

9. The face of a toiling ox thou shalt not strike with a goad.

10. My knees go, my feet are unwearied; but a fool has cut into my course.

11. His ass I am; I am harnessed to a mule; a wagon I draw, to seek reeds and fodder I go forth. [Source: piney.com]

The life of day before yesterday has departed today.

13. If the husk is not right, the kernel is not right; it will not produce seed.

14. The tall grain thrives, but what do we understand of it? The meager grain thrives, but what do we understand of it?

15. The city whose weapons are not strong the enemy before its gates shall not be thrust through.

16. If thou goest and takest the field of an enemy, the enemy will come and take your field.

17. Upon a glad heart oil is poured out of which no one knows.

18. Friendship is for the day of trouble; posterity for the future.

19. An ass in another city becomes its head.

The idea is similar to Matthew 13:57: "A prophet is not without honor, save in his own country, and in his own house."Writing is the mother of eloquence and the father of artists.

21. Be gentle to your enemy as to an old oven.

Do not gloat when your enemy falls; when he stumbles, do not let your heart rejoice,

22. The gift of the king is the nobility of the exalted; the gift of the king is the favor of governors.

A king delights in a wise servant, but a shameful servant incurs his wrath. Proverbs 14:35

23. Friendship in days of prosperity is servitude forever.

A man of many companions may come to ruin, but there is a friend who sticks closer than a brother. Proverbs 18:24

24. There is strife where servants are, slander where anointers anoint.

Fear the LORD and the king, my son, and do not join with the rebellious, Proverbs 24:21

25. When you see the gain of the fear of god, exalt god and bless the king.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024