Home | Category: Life, Families, Women

LIFE IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIAN

Ishtar, Queen of Night The development of written language in Mesopotamia provides historians and archeologists, scientists who study past cultures, with information about daily life in the distant past. Descriptions of how the people of Mesopotamia acted toward one another, how they dressed and cleaned themselves, how they prepared for weddings, how they organized businesses, and how they ruled by law are among the things that are recorded in written language.

Umbrellas were used in Mesopotamia as early as 1400 B.C. for protection from the sun not rain and they were also symbols of status and rank.

Clay tablets show banquets, family gatherings, women preparing food. Items found in the grave of Queen Pu-abi included jewelry, seashells with cosmetics, a four-foot gold drinking straw, pins, wreaths, diadems, gold tweezers, and translucent alabaster bowls.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Everyday Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Stephen Bertman (2002) Amazon.com;

“Letters from Early Mesopotamia” by Piotr Michalowski and Erica Reiner (1993) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamia: Life in the Cradle of Civilization” by Amanda H Podany (2018) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Karen Rhea Nemet-Nejat (1998) Amazon.com;

“Society and the Individual in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Laura Culbertson, Gonzalo Rubio (2024) Amazon.com;

“Everyday Life in Babylon and Assyria” by Georges Contenau (1954) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian World” by Gwendolyn Leick (2007) Amazon.com;

“Neo-Babylonian Letters and Contracts from the Eanna Archive” (Yale Oriental Series: Cuneiform Texts) by Eckart Frahm and Michael Jursa (2011) Amazon.com;

“Tying the Knot: Marriage Customs in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Oriental Publishing (2024) Amazon.com;

“Women's Work: The First 20,000 Years” by Elizabeth Wayland Barber (1994) Amazon.com;

“Law and Gender in the Ancient Near East and the Hebrew Bible” by Ilan Peled (2019) Amazon.com

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

Mesopotamian Customs

The custom of handshaking has been traced back to ancient Egypt. Hieroglyphics, dating back to 2800 B.C., representing the verb "to give," show an extended hand. Kings in ancient Babylon and Assyria grasped the hands of statues of their major Gods during important celebrations and festivals. A 9th century Assyrian relief is the first known depiction of people shaking hands.

Tablets from Nuzi also indicate it was customary for males to sell their birthright to their brothers, as Esau did to Jacob. In one case a brother agreed to exchange his inheritance for "three sheep immediately from his brother Tupkitilla." The Sumerians simply tossed their rubbish in the streets, gradually raising the level of their cities as garbage accumulated over hundreds of generations.

Private Letters in Mesopotamia

Among the early Babylonian documents found at Sippara, are two private letters of the same age and similar character. The first is as follows: “To my father, thus says Zimri-eram: May the Sun-god and Marduk grant thee everlasting life! May your health be good! I write to ask you how you are; send me back news of your health. I am at present at Dur-Sin on the canal of Bit-Sikir. In the place where I am living there is nothing to be had for food. So I am sealing up and sending you threequarters of a silver shekel. In return for the money, send some good fish and other provisions for me to eat.” [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

The second letter was despatched from Babylon, and runs thus: “To the lady Kasbeya thus says GimilMarduk: May the Sun-god and Marduk for my sake grant thee everlasting life! I am writing to enquire after your health; please send me news of it. I am living at Babylon, but have not seen you, which troubles me greatly. Send me news of your coming to me, so that I may be happy. Come in the month of Marchesvan (October). May you live for ever for my sake!” It is plain that the writer was in love with his correspondent, and had grown impatient to see her again. Both belonged to what we should call the professional classes, and nothing can better illustrate how like in the matter of correspondence the age of Abraham was to our own.

Mesopotamian Homes

Houses in Mesopotamia tended to be small and crowded. They were often clustered around the central temple or on narrow lanes. Most Mesopotamians lived in mud-brick homes. The mud bricks were held together with plaited layers of reeds. They were made in molds, dried in the sun and fired in kilns. The houses of the poor were built of reeds plastered with clay. The Sumerians used bitumen mortar. The sticky black substance helped preserve structures such as the ziggurat of Ur. The tar was one of the first uses of southern Iraq's oil fields.

Claude Hermann and Walter Johns wrote in the Encyclopedia Britannica:“Houses were let usually for the year, but also for longer terms, rent being paid in advance, half-yearly. The contract generally specified that the house was in good repair, and the tenant was bound to keep it so. The woodwork, including doors and door frames, was removable, and the tenant might bring and take away his own. The Code enacted that if the landlord would re-enter before the term was up, he must remit a fair proportion of the rent. Land was leased for houses or other buildings to be built upon it, the tenant being rent-free for eight or ten years; after which the building came into the landlord's possession. [Source: Claude Hermann Walter Johns, Babylonian Law — The Code of Hammurabi. Eleventh Edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, 1910-1911]

The first known bedrooms were in a Sumer palace, dated to 3500 B.C. In Sumerians homes there was usually only one bedroom irregardless of the size of the size of the family and household. The master of the house usually slept in the bedroom while family members and servants slept on couches and longues and on the floor in other rooms scattered around the house. There were pillows but they were usually made from wood, ivory or alabaster and they designed primarily to keep elaborate hairdos from getting messed up.

See Separate Article: MESOPOTAMIAN HOMES, FURNITURE AND POSSESSIONS africame.factsanddetails.com

Urban Life and Mesopotamia Cities

The expression “urban revolution “ has been used to describe the creation of the world’s first cities in Mesopotamia and the development of all the institutions and system that could keep these cities going. As urban life developed, society became more complex.

Mesopotamian cities tended to be located on strategic sites near water. Around the town were planted fields of grain and herds of goats and sheep. In the middle of cities were ziggurats. After a city was sacked, the city tended to be rebuilt on the same site. Some weaker cities were sacked about once a generation.

Many of the first Mesopotamia cities were first occupied around 5500 B.C. and developed into cities between 3500 and 2500 B.C. The largest cities in Mesopotamia in the third millennium B.C. had only around 20,000 or 30,000 people. The Sumerians built their cities on artificial mounds so they were protected from flood waters.

Mari

A cuneiform tablet described a Mesopotamian city as a "mighty fortress in the heart of the land." A typical Mesopotamian city was surrounded by a high wall, guarded by elite troops and occupied by various kinds of public buildings, including a royal palace, with workshops, grain storage areas, and rooms for the musical education of the royal daughters.

The main temple was often located at the center of city. Around it were workshops for pottery makers, beer brewers, bread makers, leatherworkers, spinners, weavers, clothes makers, metalworkers, tool and weapons makers, and jewelers.

City dwellers in Mesopotamia drew water from the river for irrigation canals and had no drains. In contrast, the people in the Indus valley had sophisticated sewers and drainage systems.

Market Areas of Babylon and Nineveh

In front of the city gate of Babylon was an open space, the rébit, such as may still be seen at the entrance to an Oriental town, and which was used as a market-place. The rébit of Nineveh lay on the north side of the city, in the direction where Sargon built his palace, the ruins of which are now known as Khorsabad. But besides the market-place outside the walls there were also open spaces inside them where markets could be held and sheep and cattle sold. Babylon, it would seem, was full of such public “squares,” and so, too, was Nineveh. The suqi or “streets” led into them, long, narrow lanes through which a chariot or cart could be driven with difficulty. Here and there, however, there were streets of a broader and better character, called suli, which originally denoted the raised and paved ascents which led to a temple. It was along these that the religious processions were conducted, and the King and his generals passed over them in triumph after a victory. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

One of these main streets, called Â-ibursabu, intersected Babylon; it was constructed of brick by Nebuchadnezzar, paved with large slabs of stone, and raised to a considerable height. It started from the principal gate of the city, and after passing Ê-Saggil, the great temple of Bel-Marduk, was carried as far as the sanctuary of Ishtar. When Assur-bani-pal's army captured Babylon, after a long siege, the “mercy-seats” of the gods and the paved roads were “cleansed” by order of the Assyrian King and the advice of “the prophets,” while the ordinary streets and lanes were left to themselves.

It was in these latter streets, however, that the shops and bazaars were situated. Here the trade of the country was carried on in shops which possessed no windows, but were sheltered from the sun by awnings that were stretched across the street. Behind the shops were magazines and store-houses, as well as the rooms in which the larger industries, like that of weaving, were carried on. The scavengers of the streets were probably dogs. As early as the time of Hammurabi, however, there were officers termed rabiani, whose duty it was to look after “the city, the walls, and the streets.” The streets, moreover, had separate names. Here and there “beer-houses” were to be found, answering to the public- houses of to-day, as well as regular inns. The beer-houses are not infrequently alluded to in the texts, and a deed relating to the purchase of a house in Sippara, of the age of Hammurabi, mentions one that was in a sort of underground cellar, like some of the beer-houses of modern Germany.

Mesopotamian Drugs

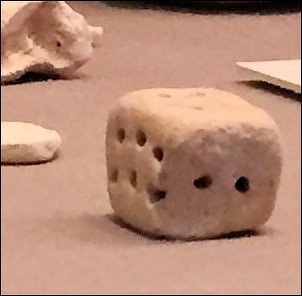

Dice from the Akkadian period

The Egyptians and Sumerians were probably using opium 4,000 years ago. Poppy extract was used ancient Egypt to quiet crying children. The oldest known opium cultivators were people who lived around a Swiss lake in the fourth millennium B.C.

Sumerian, Babylonian and Assyrian texts refer to the medicinal uses of opium beginning around 4,000 years ago. Some believe the Sumerian had opium around 3,000 B.C. suggested by the fact they seem to have an ideogram for it which also meant joy or rejoicing.

The first written record of opium use was in a 5,000-year-old Sumerian text.

LSD, a man-made drug, was first synthesized from ergot, a common fungus, also known as rye mold, in 1938. The Assyrians used ergot in ancient times as a treatment for controlling bleeding caused from childbirth.

On the use of cannabis by the Sumerians, John Alan Halloran wrote in sumerian.org: cuneiform tablets include the word — “u2 a-zal-la2 — a medicinal plant, probably distilled into a narcotic (described as "a plant for forgetting worries"); cannabis sativa, hashish ('liquid' + 'to have time elapse' + nominative). From a period 2000 years later, we know the Akkadian word shim qunnabu. There are many references in Google to qunnabu. The best reference in Google for a-zal-la is at ukcia.org/research/abel [Source: John Alan Halloran, sumerian.org]

See Earliest Evidence of the Opium Trade — from Cyprus under LIFE, ART AND CULTURE IN ANCIENT CYPRUS africame.factsanddetails.com ; 3,500-Year-Old Opium Found in Ancient Canaanite Grave Under CANAANITE FOOD, DRINK, DRUGS, CLOTHES, JEWELRY africame.factsanddetails.com

Letters from Ancient Mesopotamia

Letters which have been found on the site of Nineveh come from the royal archives and are therefore with few exceptions addressed to the King, those which have been discovered in Babylonia have more usually been sent by one private individual to another. They represent for the most part the private correspondence of the country, and prove how widely education must have been diffused there. Most of them, moreover, belong to the age of Hammurabi or that of the kings of Ur who preceded the dynasty to which he belonged, and thus cast an unexpected light on the life of the Babylonian community in the times of Abraham. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Excavations at the ancient Anatolian city of Kanesh in Turkey have revealed a district where merchants from the distant Mesopotamian city of Assur in Iraq lived and worked. Some 23,000 cuneiform tablets, mostly dating from about 1900 to 1840 B.C., have been found in the merchants’ personal archives in Kanesh.

Durrie Bouscaren wrote in Archaeology magazine: The parents of an Assyrian woman named Zizizi were furious. Like many of their neighbors’ children, their daughter had dutifully wed an Assyrian merchant. Sometime around the year 1860 B.C., she had traveled with him to the faraway Anatolian city of Kanesh in modern-day Turkey, where he traded textiles. But her husband passed away and, instead of returning to her family, Zizizi chose to marry a local. “Before god, you do not treat me, your father, like a gentleman! You have left the family!” wrote her father, Imdi-ilum, using a reed stylus to press neat wedge-shaped, or cuneiform, characters into a small clay tablet. Zizizi’s mother, Ishtar-bashti, also signed the missive. Her parents did not explicitly state disapproval over Zizizi’s choice of husband — in fact, as they reminded her, they had financially supported her second marriage. But they resented the fact that after her marriage, she hadn’t done more to help their family business of exporting textiles to Anatolia.“ We are not important in your eyes,” they seethed. [Source: Durrie Bouscaren, Archaeology magazine, November/December 2023]

The texts uncovered at Kültepe form the earliest significant corpus of correspondence in the world, but fewer than half of them have been translated and published. Most of the tablets were preserved by chance. Around 1835 B.C., a fire destroyed Kanesh, baking and hardening many of the clay tablets stored in the archives of private homes. While it’s possible the blaze was accidental, most researchers believe it may have been an act of war. “Kanesh was destroyed in exactly the right way,” says Gojko Barjamovic, a Harvard University Assyriologist who has focused much of his career on the tablets unearthed at Kanesh. “People got out — there are no dead people in the houses, there are no skeletons in the fire — they must have been warned. But they couldn’t take their archives with them.” These private archives contain not just personal letters from Assyrian merchants’ families, such as the one from Zizizi’s parents, but also records of financial transactions, debts, and contracts. Many tablets were unearthed during clandestine digs in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and then dispersed to museums all over the world. A team working at the site today, led by Ankara University archaeologist Fikri Kulakoğlu, continues to discover more.

Recreation in Mesopotamia

tablet with a Kurdish mastiff

Hunting was perhaps the most popular recreational activity among the upper classes and royalty. Friezes from Nivenuh show the Assyrian ruler Ashurbanipal II riding a chariot, hunting a lion with a bow and arrow and killing a lion with a spear while another lion tries to leap on a horse. Royal hunts depicted in these images were ceremonial affairs in which w lion was released from a cage and surrounded by soldiers who forced it to fight with the king and no doubt stepped in if it looked as if the lion was going to get the upper hand.

:King Ashurbanapal in Lion Hunt and pouring Libations over Four Lions killed in the Hunt” on an alabaster slab “is one of a large series illustrative of the royal sport in Assyria—hunting lions, wild horses, gazelles, and other animals...Ashurbanapal with his attendants behind him is pouring a libation over four lions killed in the hunt. An altar is in the centre, and a pole or tree such as is often seen on the seal cylinders when sacrificial scenes are portrayed. The musicians to the left precede the attendants carrying a dead lion on their backs...These slabs formed the decoration of portions of the walls in the large halls of the palace of Ashurbanapal at Kouyunjik (Nineveh). They were found by Layard and are now one of the great attractions of the British Museum. As specimens of the art of Assyria they are of deep interest, but no less as illustrations of life and manners, supplemented by the equally extensive series of slabs which illustrate the campaigns waged by this king. Similar martial designs in the palace of Sargon at Khorsabad illustrating his campaigns. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

Describing what a royal banquet might have been like 2700 years ago in the palace at Nineveh, capital of the Assyrian Empire, Laura Kelley wrote in Saudi Aramco World: “As you arrive, the scent of lilies and roses fills the air. Musicians play harps and pipes, sing songs and recite poems. You snack on fresh pistachios and walnuts as you wait for the entrance of the king. The woman next to you stirs, and her red linen tunic crinkles slightly against her fine cotton shawl. Her gold earrings softly jingle as she moves. With her, you discuss your admiration for King Ashurbanipal, a learned man and, as you see him, a benevolent ruler. He is a generous patron of artists, astronomers and mathematicians in his court. On military and diplomatic missions, he has directed that his envoys collect plants, seeds, animals or anything unusual from the foreign lands they pass through; when they return, their finds have been placed in palace gardens, zoos and rooms filled with curiosities. [Source: Laura Kelley, Saudi Aramco World, November/December 2012, saudiaramcoworld.com ]

Toys and Pets in Ancient Mesopotamia

Based on texts from cuneiform tablets and images on Mesopotamian art, the Sumerians had big parties; Assyrian warriors appeared to have swum the crawl; and oryxes and other kinds of antelope were kept as household pets.

Tops were used in Babylonia as early as 3000 B.C. Clay tops, etches with images of animals of human figures, have been found in children’s graves dating back to that period.

Many of the animals that we think of as existing only in sub-Sahara Africa — like antelopes, hyenas, and lions — were found in Mesopotamia 4000 years ago. Tigers roamed Iran and cheetahs were found in India. It doesn’t seem far-fetched they they were found in Mesopotamia too.

There’s a Sumerian proverb which notes that “a dog licks its shriveled penis with its tongue.” In antiquity necrophagia, or corpse eating, was associated with dogs as they were known for feasting on unburied corpses.

Games in Ancient Mesopotamia

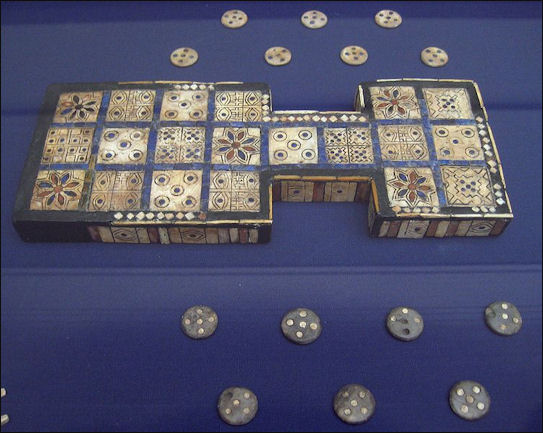

In 1920, British archaeologist Leonard Woolley discovered what is believed to be the world's oldest board game among the ruins at Ur. Dated to 3000 B.C., the game consisted of six pyramidal dice, three white and three lapis lazuli, and seven marked pieces moved by the players. The rules of the game are unknown until the 1980s when a curator at the British Museum named Irving Finkel translated a Babylonian clay tablet which turned out to be a description of the rules. People that played the game, also known as the Game of Twenty Squares, had either evolved into or had been replaced by the game we know today as Backgammon.

In December 2021, archaeologists working in Oman discovered a 4000-year-old board game dating thought to an ancient predecessor of Backgammon. The archaeologists were part of an excavation undertaken by the Polish Center of Mediterranean Archaeology at the University of Warsaw, and Oman’s Ministry of Heritage and Tourism, took place in the Qumayrah Valley, and made all kinds of cool (for archaeologists, anyway) Bronze Age discoveries, like some big towers, and evidence the settlement was part of the copper trade. [Source: Luke Plunkett, Kotaku, January 27, 2022]

Royal Game of Ur

“But the most unexpected discovery is not related directly to economy or subsistence. — In one of the rooms we’ve found… a game-board! — beams the project director. The board is made of stone and has marked fields and cup-holes. Games based on similar principles were played during the Bronze Age in many economic and cultural centers of that age. — Such finds are rare, but several examples are known from India, Mesopotamia and even the Eastern Mediterranean basin. The most famous example of a game-board based on a similar principle is the one from the graves from Ur, — explains the archaeologist.

“Like the summary suggests, while the game found in the Qumayrah Valley is something of a mystery, it’s at least similar to the Royal Game of Ur, one of the most famous board games of antiquity.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024