Home | Category: Jewish Marriage and Family

JEWISH WEDDING

George P. Monger wrote in “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “Judaism prescribes that a marriage be a community event and should not take place in private. Indeed, if a bride or her family are not able to afford a large wedding, a collection may be taken from the community to ensure that the celebrations are carried through properly. There are nine elements in the Jewish wedding: the chuppah (canopy); the signing of the ketubah; the bedeken, the veiling of the bride; the seven circuits; the kiddushin, the betrothal ceremony; the nissuin, the marriage ceremony; the breaking of the glass; the signing of the civil register; and the yichud, the time of seclusion or privacy. There are questions concerning when they were introduced and disputes concerning whether or not the wedding should take place inside a synagogue because a ceremony held inside a building is reminiscent of Gentile practice. [Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ by George P. Monger, 2004 ^]

Caroline Westbrook wrote for SomethingJewish.co.uk: “The rituals associated with Jewish weddings begin as soon as a couple are engaged, with a ceremony known as tena'im. It involves breaking a plate to symbolise the destruction of the temples in Jerusalem, as a reminder that even in the midst of celebration Jews still feel sadness for their loss. This is a theme that is repeated at the ceremony of itself with the breaking of the glass. [Source: Caroline Westbrook, SomethingJewish.co.uk, July 24, 2009, BBC |::|]

Websites and Resources: Virtual Jewish Library jewishvirtuallibrary.org/index ; Judaism101 jewfaq.org ; torah.org torah.org ; Chabad,org chabad.org/library/bible ; BBC - Religion: Judaism bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/judaism ; Encyclopædia Britannica, britannica.com/topic/Judaism; Yivo Institute of Jewish Research yivoinstitute.org ; Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Aish.com aish.com ; Jewish Museum London jewishmuseum.org.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Jewish Wedding Now” by Anita Diamant Amazon.com ;

“The Jewish Wedding Companion” (complete liturgy and explanations) by Rabbi Zalman Goldstein Amazon.com ;

“Holy Intimacy: The Heart and Soul of Jewish Marriage” by Sara Morozow and Rivkah Slonim Amazon.com ;

“Jewish Marriage: How to Achieve the Ideal Marital Relationship” by Yosef Malka Amazon.com ;

“Choosing a Jewish Life, Revised and Updated: A Handbook for People Converting to Judaism and for Their Family and Friends” by Anita Diamant, Barrie Kreinik, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Living a Jewish Life: Jewish Traditions, Customs, and Values for Today's Families” by Anita Diamant, Howard Cooper, et al. Amazon.com ;

“To Be a Jew Today: A New Guide to God, Israel, and the Jewish People”

by Noah Feldman Amazon.com ;

“Essential Judaism: Updated Edition: A Complete Guide to Beliefs, Customs & Rituals”

by George Robinson Amazon.com ;

“Living Judaism: The Complete Guide to Jewish Belief, Tradition, and Practice”

by Wayne D. Dosick Amazon.com ;

“Judaism: History, Belief and Practice” by Dan Cohn-Sherbok Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jews” by Paul Johnson, Amazon.com

When and Where Jewish Weddings Are Held

Jewish weddings are held at synagogues, homes, wedding halls, hotels or outdoors. They are usually not held on the Sabbath or a Jewish holiday. At Orthodox weddings, a minyian with at least 10 men must be present.

Caroline Westbrook wrote for SomethingJewish.co.uk: “The wedding itself can be held on any day of the week apart from during the Jewish Sabbath, which runs from sunset on Friday until sunset on Saturday, or on major Jewish festivals such as the Day of Atonement or Jewish New Year (when Jews are required to refrain from work). In the UK, Sunday is the most popular day for Jewish weddings to be held - in countries such as the US it is also common for weddings to be held on Saturday night after the Sabbath. (This is more popular in the winter when Sabbath ends early.) Ultra-Orthodox couples often hold ceremonies on weekdays. [Source: Caroline Westbrook, SomethingJewish.co.uk, July 24, 2009, BBC |::|]

“There is no specific time of year when a wedding cannot take place, although many couples tend to avoid the period between the festivals of Pesach (Passover) and Shavuot which is known as the Omer and is a reflective and sad time in the Jewish calendar. As many people refrain from parties involving music and dancing during this period, it is not considered to be a good time to hold a wedding. However, this is more of an Orthodox tradition. |::|

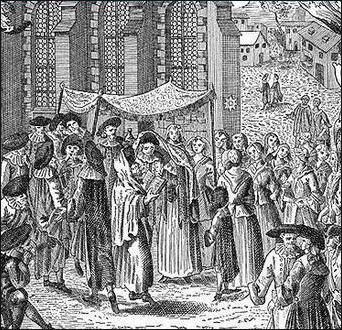

Chuppah — the Jewish Wedding Canopy

Jewish wedding ceremonies are often held under or inside a chuppah or chuppa (canopy), which symbolizes the new home, the basis of Jewish life, for the newlyweds. It is open on all four sides, to represent hospitality, and bare with no floor to indicate that it is not physical or material things that make a good marriage but the love and affection and sacrifice of each partner and the spiritual richness with which they invest their home. European Jews have traditionally set up the chuppah outside under the sky to recall God’s blessing to Abraham that his children will be as “numerous as the stars in Heaven.” At an Orthodox ceremony the chuppah is held aloft by four men while the wedding ceremony is conducted. The mothers of the bride and groom accompany the bride as she walks to the chuppah and the fathers of the bride and groom accompany the groom as he walks to the chuppah.

Jewish wedding ceremonies are often held under or inside a chuppah or chuppa (canopy), which symbolizes the new home, the basis of Jewish life, for the newlyweds. It is open on all four sides, to represent hospitality, and bare with no floor to indicate that it is not physical or material things that make a good marriage but the love and affection and sacrifice of each partner and the spiritual richness with which they invest their home. European Jews have traditionally set up the chuppah outside under the sky to recall God’s blessing to Abraham that his children will be as “numerous as the stars in Heaven.” At an Orthodox ceremony the chuppah is held aloft by four men while the wedding ceremony is conducted. The mothers of the bride and groom accompany the bride as she walks to the chuppah and the fathers of the bride and groom accompany the groom as he walks to the chuppah.

George P. Monger wrote in “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ According to many writers, especially early Jewish writers, the chuppah was originally the groom’s house or a room or building other than the bride’s parental home. By entering the chuppah, she cut her ties with her family and came under the protection of her new husband.

The seclusion of the bride and groom (yichud or yihud) is the last part of the wedding ceremony, and today there is a separate room in the synagogue for the couple to break their fast in privacy. It is likely from early writings that the chuppah was originally the place for seclusion for the yichud. [Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ by George P. Monger, 2004 ^]

However, there was considerable confusion among medieval writers on Jewish religious law about what was being referred to in the Talmud when the chuppah was mentioned. A twelfth-century rabbi — Rabbi Isaac ben Abba Mari — said that it was customary to decorate the room for the seclusion — which was designated the chuppah — with colorful tapestries and cloths, or with myrtle leaves and roses. Rabbi Isaac also mentioned with disapproval the practice of holding a cloth, or talit, over the couple while marriage prayers and blessings were recited. So there seems to have been a definite difference between the chuppah and other forms of canopies. It was not until the sixteenth century that the familiar four-posted canopy came to be used, albeit with reluctance on the part of the rabbis.

“But there was great reluctance even for weddings to take place within the synagogue — because they involved actions inappropriate for a sacred place that should be used only for religious study and prayer, i.e., at a wedding the clothing of the congregation is not always suitable for a sacred place, and the free mixing of the sexes is also a problem. And traditionalists saw the synagogue wedding as an imitation of the Christian practice. Consequently, many authorities believed that the chuppah should be set up outside, and there was a custom in Ashkenazic communities to hold weddings in the synagogue courtyard. The chuppah set up outside, under the heavens, further symbolizes the hope that descendants will be as plentiful as the stars in heaven.

Chuppah Traditions and History

George P. Monger wrote: Traditionally the canopy, the chuppah or chuppa, was erected in the courtyard of the bridegroom’s house or in the courtyard of the synagogue. It was said that the canopy should be placed beneath the heavens to symbolize that offspring would be as plentiful as the stars in the heavens. Kibbutz weddings often take place in the open, using a canopy made from the Israeli flag. The canopy was often decorated with flowers and green leaves and sometimes cloths and tapestries. The canopy is sometimes seen as a survival of the bridal bower where the couple went to consummate the marriage after the ceremonies. Some rabbinical authorities say that the chuppah was the groom’s house or a room or any other building than the bride’s parental home, where, by entering, she declares her independence from her parents and accepts the protection of her husband. However, the seclusion portion of the wedding is now known as yichud, or seclusion or privacy, and the canopy is interpreted as representing the (new) home, the basis for Jewish life, open on four sides to represent hospitality. [Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ by George P. Monger, 2004]

fancy chupah During the nineteenth century, there was controversy as to whether the chuppah should be erected within the synagogue, with the suggestion that to do so was to make Jewish practice imitate Gentile custom. However, it should be noted that in Christian tradition, the betrothal and wedding took place outside the church, at the church door, with the wedding being blessed in church. Gradually the church took over the officiating at weddings inside the church. But the marriage “service” takes place beneath the canopy — even in the synagogue — which may suggest that the canopy has a function similar to that of other cultures. Rabbi Isaac ben Abba Mari, writing in the twelfth century, mentioned a custom, of which he disapproved, of holding a cloth or a talit over the heads of the couple during the marriage blessing, which sounds analogous to the fourteenth-century practice in England mentioned above. In Sweden, the bridesmaids hold a canopy over the bride made of shawls to protect her from the evil eye.

The earliest references to the four-posted canopy among Jewish communities did not occur until the sixteenth century and it appears to have been accepted with reluctance. When the couple stands beneath the chuppah, the balance of power within the marriage can be determined by where they place their feet during the ceremony. If the man puts his right foot on the woman’s left foot during the blessing, he will have authority over her in the marriage; however, if she manages to put her left foot on his right then she will have the power in the household. There is a story of a bride who lost this competition, so her father recommended that before the consummation of the marriage she ask her husband to bring her a glass of water. Drinking this would shift the focus of the household power.

Canopies used in some marriage ceremonies are sometimes seen as a form of protection from the evil eye. At marriage ceremonies among the Jews of Tunis, after the religious ceremony, the bride is taken into an upper room, accompanied by all her friends, who remain with her. The bridegroom retires with his friends, without taking the slightest notice of the bride. She is seated on a chair placed upon the usual divan. Her mother-in-law now comes forward, unveils her, and with a pair of scissors cuts off the tips of her hair. This last ceremony is supposed to be of great importance in driving away all evil influences that might do harm to or come between the newly married pair.

Jewish Wedding Clothes

The bride usually wears a white dress and a veil over her head as a sign of purity. The groom at an Orthodox wedding typically wears a kippah (yarmulke, Jewish head covering) and a prayer shawl over a suit. Sometimes he has ashes placed on his forehead to recall the destruction of the Temple. For good luck the bride and groom have traditionally not looked at each other until the veil is lifted. The veil recalls Rachel’s deception when Jacob married Leah. The ceremony is usually conducted by a rabbi. Chants, music and prayers in Hebrew are provided by a “cantor” .

Caroline Westbrook wrote for SomethingJewish.co.uk: ““There is no specific traditional dress for a Jewish wedding. Men will often wear black tie or morning suit, while women usually wear a white wedding dress — however, religious background will often affect the choice outfit worn, with Orthodox women being more modest. [Source: Caroline Westbrook, SomethingJewish.co.uk, July 24, 2009, BBC |::|]

George P. Monger wrote in “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ On their wedding day the couple is viewed almost as royalty, and it is usual for the bride to stand to the right of the groom to reflect the words of Psalm 45.10: “At thy right hand doth the queen stand.” It is also a tradition that the guests should tell the groom how beautiful the bride is. Ancient rabbis, worried that in some cases this could result in the guests bearing false witness, decreed that every bride was beautiful on her wedding day and in the groom’s eyes she is without equal. There is a tradition of and seven wedding garments worn by the bride at the wedding.[Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ by George P. Monger, 2004]

Before a Jewish Wedding

Customarily, the bride and groom avoided any contact with each other for a week before the wedding. On the Shabbat (Sabbath) that falls during the week of the wedding, it is customary for the groom to be given the honor of reciting the blessing over the Torah (aliyah). On the day before the wedding, the groom and the bride both fast. Monger wrote: To help with the expense and arrangements, the groom’s friends are expected to send gifts of money to the groom. Those donating help were entitled to eat and drink with the groom during the week of wedding celebrations. These friends and acquaintances were referred to as shoshbins. The shoshbin was also traditionally the groom’s confidant, analogous to the best man at a Gentile wedding. The word in Aramaic has the sense of a close friend. The bride, too, has her shoshbin to attend and support her through the wedding. [Sources: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ by George P. Monger, 2004, Encyclopedia.com]

Customarily, the bride and groom avoided any contact with each other for a week before the wedding. On the Shabbat (Sabbath) that falls during the week of the wedding, it is customary for the groom to be given the honor of reciting the blessing over the Torah (aliyah). On the day before the wedding, the groom and the bride both fast. Monger wrote: To help with the expense and arrangements, the groom’s friends are expected to send gifts of money to the groom. Those donating help were entitled to eat and drink with the groom during the week of wedding celebrations. These friends and acquaintances were referred to as shoshbins. The shoshbin was also traditionally the groom’s confidant, analogous to the best man at a Gentile wedding. The word in Aramaic has the sense of a close friend. The bride, too, has her shoshbin to attend and support her through the wedding. [Sources: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ by George P. Monger, 2004, Encyclopedia.com]

Traditionally, in Russia, Jewish marriages were arranged by matchmakers and separate rituals took place at the bride’s and groom’s houses. Prior to a wedding, the marriage contacts was negotiated by the families of the bride and groom and an engagement party was held in which the bride brought clothing, decorations and pastries called “lkakh” . In Central Asia, after the marriage was arranaged, a bride price was offered, and a ceremonial betrothal meeting took place between the bride’s and groom’s family. At this meeting, the bride unveiled her face and bride and groom laid eyes on one another for the first time.

Caroline Westbrook wrote for SomethingJewish.co.uk: “The week before the wedding is an exciting time. A special ceremony is arranged for the groom known as an Ufruf. This involves him going to the synagogue and taking an active part in the service, as well as announcing the impending wedding to the congregation. Often when the groom is playing his part in the service, members of the congregation will shower him with sweets, (younger members of the community tend to throw harder, in a jovial manner!). On many occasions the service is followed by refreshments in the synagogue (known as a kiddush), where platters of food, drink and wine will be served to congregants. This is also often followed by a private celebration lunch for the respective families. [Source: Caroline Westbrook, SomethingJewish.co.uk, July 24, 2009, BBC |::|]

“The bride, meanwhile, will often visit the ritual bath known as the Mikveh in the week before the wedding, so that she may cleanse herself spiritually and enter marriage in a state of complete purity. Mikvehs vary from country to country - some are up to the standard of health clubs. Men sometimes visit as well in the week before their wedding, but will use separate facilities. In order to properly fulfill the requirements of the mikveh, the woman must remove all jewellery and even nail polish before entering the bath and must fully immerse herself in the water while reciting a special prayer. She will be supervised and assisted during the ritual to ensure it is done correctly. |::|

“It is also traditional for the bride and groom not to see each other in the week before the wedding, although as in other religions it is less common these days. Jews are traditionally married underneath a special canopy known as a chupa, which symbolises the home that the couple will share. The ceremony used to take place outdoors in a field or grounds. Nowadays, it is more common for the ceremony to be held indoors to avoid any problems with the weather, though some people still have the ceremony outdoors. More often than not the ceremony takes place in a synagogue, but there is no rule saying that it must be held in a synagogue - as long as the chupa is present and the ceremony is under a rabbi's supervision it can be held anywhere - these days it is increasingly common to hold Jewish weddings in hotels and other venues.” |::|

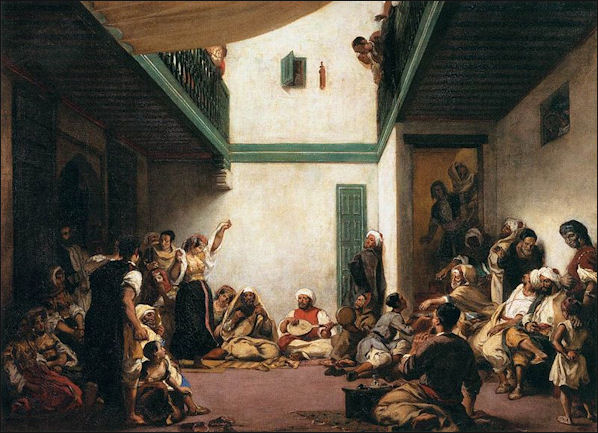

Delacroix painting of a Jewish wedding in Morocco

Jewish Wedding Day and Marriage Contract

On the day of the ceremony for an Orthodox wedding the bride and groom usually fast all day and say a special prayer in the afternoon. Fasting is a symbolic statement. Just as Jews fast on Yom Kippur — the Day Of Atonement — to cleanse themselves of their sins and start afresh — so Jews fast on their wedding day to “cleanse themselves of sin and come to their marriage with a clean slate.” [Source: Caroline Westbrook, SomethingJewish.co.uk, July 24, 2009, BBC |::|]

Sometime before the wedding, a ketubah (marriage contract) is drawn up, and it is read aloud at the marriage ceremony; it contains, among other things, the bride-groom's promise to the bride: "I will work for you. I will honor you. I will support and maintain you as befits a Jewish husband." [Source: J.M Oesterreicher, New Catholic Encyclopedia, 1960s, Encyclopedia.com]

George P. Monger wrote in “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “Before the ceremony the groom reads and accepts all the terms of the marriage contract, the ketubah. This outlines the duties and responsibilities of the husband to provide food, clothing, and conjugal rights. The groom, by accepting this contract, allows the rabbi to read this to the bride at a later stage of the ceremony. The ketubah is then witnessed. Bedeken, or the veiling of the bride, comes from the Hebrew word meaning to check and recalls the story of Jacob being tricked into marrying Leah, Rachel’s older sister. [Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ by George P. Monger, 2004 ^]

The groom is escorted to the bride’s room where he confirms that the woman is the right one. After lifting the veil over the bride’s face, the rabbi blesses the bride with words from the blessing given to Rebekah on her marriage to Isaac: “Our sister, may you become the mother of thousands of ten thousands” (Gen. 24.60), and adds, “The Lord make you as Sarah, Rebekah, Rachel and Leah.” The bride and groom are conducted to the chuppah by the couple’s parents. This is considered to be a mitzvah — a privilege and an honor. The bride wears no jewelry or other ornament, signifying that the couple are equal at the beginning of their new life together.

Jewish Wedding Ceremony

A Jewish wedding ceremony combines a betrothal ceremony, a marriage ceremony, and a public joining of the couple to become an individual family unit. During the wedding ceremony the veiled bride approaches the groom and circles around him. Then, after two blessings are recited over wine, the groom places a ring on the bride's finger and recites the words "Be sanctified to me with this ring in accordance with the law of Moses and Israel." Jewish law does not require a rabbi to be present, but one normally is for civil rather than religious reasons. [Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ by George P. Monger, 2004 ^]

During a wedding ceremony, the couple and their parents stand under a wedding canopy, or chuppah, symbolizing the marriage chamber or home, and the ketubah, or marriage contract, is often read out loud (usually in Aramaic and with a translation into the language of the couple being married). Jewish weddings combine two ceremonies into one event — the kiddushin, the betrothal ceremony, and the nissuin, the marriage ceremony. In the Reform marriage ceremony, chuppa and ketûbâ are almost always omitted, as well as the reference to the restoration of the Holy City. Other English prayers, however, for the wellbeing of the bride and bridegroom, are added.

wedding chupah Caroline Westbrook wrote for SomethingJewish.co.uk: “Although the ceremony has to be under a rabbi's supervision - as they will be familiar with all the laws and customs of the wedding - it does not necessarily have to be performed by a rabbi, as long as one is present. Most couples opt to have a rabbi conduct the ceremony, although it can be performed by a friend or family member, provided they have the permission of a rabbi. [Source: Caroline Westbrook, SomethingJewish.co.uk, July 24, 2009, BBC |::|]

At a reform wedding: 1) the rabbi blesses the couple about to be married; 2) the ketubah is signed in a private room followed by the couple reciting a special prayer; 3) the rabbi says some opening words; 4) a prayer of gratitide is offered by the congregation followed by a speech about uniting couples by the rabbi; 5) the rabbi(s) praise(s) God and then the congregation praises God with special prayers; 6) the couples sips wine and says their vows; 7) the rabbi read the ketubah; 8) the rabbi and then the congregation says a closing prayer; 9) the groom break a glass with his foot.

See Separate Article: JEWISH WEDDING CEREMONY africame.factsanddetails.com

Jewish Wedding Customs and Symbols

Caroline Westbrook wrote for SomethingJewish.co.uk: “There is no rule as to what music can and cannot be played during the ceremony, although many couples feel uncomfortable playing music by Wagner (such as The Wedding March) due to his anti-Semitic viewpoints and popularity with Germany's Nazi party during the 1930s and 1940s. Most couples opt for traditional Jewish music to be played during the entrance of the bride and after the service - much of this is centuries old. |::|

“There is also no firm rule about who escorts the bride to the Chupa, but traditionally it is the bride's father who accompanies her (sometimes both parents will do so). The bride is the last person to enter, and upon reaching the Chupa will walk round the bridegroom several times - this number varies. Some brides walk around their husband-to-be once while more Orthodox brides walk round seven times.” |::|

“The number seven is significant in the Jewish wedding - for example seven cups of wine are drunk during the ceremony and celebrations afterwards. This is because God created the world in seven days and so the groom and the bride are symbolically creating the walls of the couple's new home. [Source: Caroline Westbrook, SomethingJewish.co.uk, July 24, 2009, BBC |::|]

“During the service, the bride and groom drink the first of the seven cups of wine, and several prayers are said binding the couple together. One of the most important parts is the giving of the ring. The ring itself must belong to the groom - it must not be borrowed - and must be a complete circle without a break, to emphasise the hope for a harmonious marriage, and must be plain without stones or decoration. It is not a requirement for the groom to wear a wedding ring, but many men do. As with other religions, the ring is held by the best man until it is time for the groom to give it to the bride. When the groom gives the bride the ring he recites the following verse: Behold you are consecrated to me with this ring according to the laws of Moses and Israel.” |::|

After the Jewish Wedding Ceremony

After the University wedding ceremony, it is traditional for the newlyweds to spend some time alone together in a special room before greeting their guests. In this room, often the bride’s room before the ceremony, the couple have some moments of privacy — yichud — and they break their fast. Their wedding day fast is considered their own Yom Kippur.

George P. Monger wrote in “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “After the ceremony, the guests will join in the celebrations and enjoy themselves as an obligation to make the bride and groom happy on their own special day. Money is scattered among the crowd as a reminder, that the guests had been present at the wedding; and barley also is thrown before the newly married couple, symbolizing their wish for many children. [Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ by George P. Monger, 2004 ^]

According to the BBC: As with all communities and religions, Jews like to film their weddings and take photographs, and often this is done between the ceremony and the wedding party. Sometimes, especially in the case of evening weddings, the official photographs will be taken before the ceremony to make best use of the time available.” |::|

Jewish Wedding Party

Weddings are a time of great celebration. Different communities have different customs but traditionally the ceremony was followed by feast hosted by the bride’s family that was supposed to be so lavish it brought them to the edge of bankruptcy. There is a special commandment that states that a newlywed couple should be entertained at their wedding receptions. To achieve this a large party is held with music, dancing and food that formally begins after the bride and groom make a formal entrance and are introduced and Mr. And Mrs.

Weddings are a time of great celebration. Different communities have different customs but traditionally the ceremony was followed by feast hosted by the bride’s family that was supposed to be so lavish it brought them to the edge of bankruptcy. There is a special commandment that states that a newlywed couple should be entertained at their wedding receptions. To achieve this a large party is held with music, dancing and food that formally begins after the bride and groom make a formal entrance and are introduced and Mr. And Mrs.

The party is usually held at a home or wedding hall. It has traditionally featured men and women gathering separately and doing line dances call the “hora” to Jewish folk music or klezmer music. The climax of the party is when the bride and groom are lifted on chairs surrounded by a circle of clapping and dancing guests honoring the newlyweds as they would a king and queen. At some parties the parents of the newlywed couple are also lifted.

Caroline Westbrook wrote for SomethingJewish.co.uk: “Even though some weddings take place in a synagogue, it doesn't mean that the reception will be there as well - often it is at another location such as a function hall or hotel, depending on the budget and needs of the couple, and the number of guests. The party itself can take a number of different formats, depending on how religious the couple are. Within Orthodox communities, it is likely that men and women will have separate dancing during the event, while other people will allow mixed dancing. When it comes to catering, many people opt for kosher food - however, some people who are not Orthodox or follow Orthodox tradition may have a fish meal or vegetarian meal from a non-kosher caterer. From time to time this can be difficult for some family members or friends who may keep to the dietary laws, and often special individual meals can be brought in for them. However, most couples tend to opt for kosher catering in order to avoid any problems with guests who keep kosher. [Source: Caroline Westbrook, SomethingJewish.co.uk, July 24, 2009, BBC |::|]

“Jews fall into two main ethnic camps - Ashkenazi, the Jews of European origin, and Sephardi, Jews of Middle Eastern and Spanish and Portuguese origin - and the traditions of their backgrounds will often influence the style of their wedding and of the catering requirements. Ashkenazi Jews often serve common staple foods such as roast chicken, potatoes and vegetables, as the main course, while Sephardis may have lamb or some spicy chicken with couscous or rice. |::|

“Many other aspects of the wedding party are similar to those in other religions - the best man, bridegroom and father of the bride will give speeches, presents will often be given to members of the wedding party, including mothers of the bride and groom and the bridesmaids, and music will be supplied either by a DJ or, more commonly, a band. |::| “Both DJ and band will be expected to play an element of Jewish music - Jewish dancing to traditional songs (known as a Hora) is a big part of the wedding party. More Orthodox Jews will play strictly Jewish music and Jewish themed music, while other Jews will opt for a mixture of different sounds including Jewish music. |::|

“Among the religious rituals at the party are the blessing over the Challah bread which is traditionally made before a meal, and the seven blessings which are made to the bride and groom. Often these are given as an honour to seven guests as their way of having some participation in the ceremony. After the wedding, the bride and groom will go on their honeymoon, their first chance to spend time together as husband and wife.” |::|

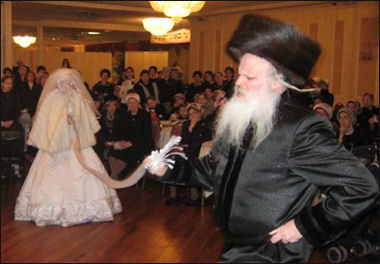

Wedding Dances of Hasidic Jews

George P. Monger wrote in “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ Hassidic Jews have a variety of specific dances for weddings, including the first dance after the ceremony, the knussen-kaleh mazel tov (bridegroom and bride, good luck); the patch tants (clap dance), an initiation dance for the bride; and the koilitch dance. The knussen-kaleh mazel tov is a farandole, danced in a snake-like line with the male relatives holding the bride’s veil, one on each side of her. In the other hand, they hold a handkerchief to which the other guests hold, forming a line. This dance is also known as a mitsveh (precept) dance. [Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ by George P. Monger, 2004 ^]

The patch tants is performed by the married women, who circle around the bride with the handkerchief held downward; during a grand chain (a right and left chain movement), the bride joins in, thus becoming one of them. Although dancing at weddings is generally a communal activity, there were also some solo or display dances performed for the couple, such as the koilitch dance — the dancer holds a loaf of white braided bread (khaleh) to signify that the couple’s home should never be without bread — and a dance performed by a beggar, who is specially invited as the couple’s first charitable act.

The dance of the kazatskies features the oldest male relative dancing to express his joy at the wedding and to demonstrate that he still has the strength to do so. During his performance, a female dancer, waving a handkerchief, dances a circle round him. The mothers-in-law may also dance the beroiges tants. At Orthodox Jewish weddings, the celebration room is divided into male and female halves so that the sexes do not actually dance together.

Jewish Wedding Customs in Russia, Central Asia and the Middle East

In Russian Jewish weddings, on the day of the wedding, the bride was traditionally dressed in beautiful clothes and her head was covered with a kerchief and was serenaded with farewell songs by her friends. The groom arrived with his entourage but was not allowed to escort the bride and her entourage until the bride price was accepted by the bride’s friends. As the wedding party made their way from the bride’s house to the groom’s house, people danced, sang and carried burning candles, lamps and torches. Friends of the groom threw rice and candles over the bride to bring her good luck and many children.

After the wedding there was a large party in which, guest would announce their wedding gifts and present them to the bride and groom, men performed dances and the bride and groom were lifted in separate chairs as was depicted in the film “Fiddler on the Roof” . These days the families of the bride and groom often collectively host a single party and share the expenses. Guests bring envelopes with money and give them to a special collector. During the wedding part, a wedding cake is cut and served, traditionally Jewish foods are served, and dancing, singing and other activities are led by designated toastmasters. Guests take turns dancing with the bride and presenting her with money.

Before a wedding in some Middle Eastern Jewish communities, the bride and groom eat bread with their families, symbolizing that they will be well provided for, with honey for sweetness. Women often sing songs with a high-pitched voice to express their happiness for the bride. In Central Asia, seven days before the wedding, the bride's dowry was displayed at [a] party for the bride. A few days before the wedding the bride was cleansed in a ritual bath called a “mikvah” , the bride’s hands were painted with henna and the marriage contract was signed.

Among some Jewish peoples, a bride-to-be has traditionally been washed in a ritual bath of cold water the day before her wedding, accompanied by a group of women who would make a big fuss during the bathing to draw attention to the fact that the young woman was to be a bride. Sometimes the ritual bathing is only applied to the feet and may have a meaning beyond simply purification. [Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ by George P. Monger, 2004]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu; “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, London, Library of Congress, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024