Home | Category: The Torah / Judaism and Jews / Judaism Beliefs

SACRED BOOKS OF JUDAISM

Talmud set Judaism is a text-centered, study-oriented religion, with a vast library of texts regarded as sacred comprised of thousands of volumes. Its foundational text is the Hebrew Bible, which is divided into three parts: 1) the Torah, forming the five books of Moses (also called the Pentateuch); 2) the Prophets (Nevi'im); and 3) the Writings (Ketuvim or Hagiographa). Jewish tradition holds the Torah to be the direct, unmediated Word of God, whereas in the Prophets men said to be divinely inspired speak in their own voices, while the Writings are considered to be formulations in the words of men guided by the Holy Spirit. [Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Devout Jews believe the words of the Written Torah, — the first five books of the Tanakh (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy) — are true and were given to Moses by God. They also believe the words of the Oral Torah — which includes the Talmud, and other traditional efforts to interpret and explain the scriptures — are not the word of God but they are accepted as true.

According to the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: Alongside the Torah and the other books of the Bible there developed an elaborate commentary explicating their teachings. This commentary was initially not written, but since it was regarded as divinely inspired, it was called the Oral Torah. Over the centuries the Oral Torah expanded to such a degree that it could no longer be contained by sheer memory. Hence, around the end of the second and the beginning of the third century A.D., Rabbi Judah the Prince (that is, the head of the supreme rabbinical council) compiled a comprehensive digest of the Oral Torah. This work, known as the Mishnah, assumed a canonical status. Written in Hebrew, the Mishnah is a multivolume work covering such subjects as the laws governing agriculture, Temple service, festivals and fast days, marriage and divorce, business transactions, ritual purity and purification, adjudication of torts, and general issues of jurisprudence. The Mishnah does not confine itself to Halakhic, or legal, matters. Under the rubric of Aggadah (narration), it contains reflections on Jewish history, ethics, etiquette, philosophy, folklore, medicine, astronomy, and piety. Typical of rabbinical discourse, the Aggadah and Halakhah are interwoven in the text of the Mishnah, complementing and amplifying each other.

Post-Mishnaic teachers and scholars in the Land of Israel and in Babylonia wrote running commentaries on the Mishnah. These commentaries, together with those on other, smaller works, were collected in two massive collections, one known as the — Palestinian, or Jerusalem, Talmud — and the other as the Babylonian Talmud. (Another term for the Talmud is Gemara, from an Aramaic word for "teaching.") These were completed around 400 and 500 A.D., respectively. The two Talmuds were written in Aramaic, a language related to Hebrew. Similar to the Mishnah, the Talmuds contain Aggadah and Halakhah woven into a single skein. In the centuries that followed numerous commentaries were written on the Talmuds, particularly on the Babylonian, which became the preeminent text of Jewish sacred learning. In the age of printing the Talmuds were published with the principal commentaries on them adorning the margins of each page.

From time to time collections of scriptural commentaries, originally in the form of sermons or lectures at rabbinical academies from the period of the Mishnah and Talmud, were made. They appear under the general name Midrash (inquiry, or investigation). The collections are classified as Halakhic and Aggadic Midrashhim. The Halakhic Midrashim focus on explicating the laws of the Pentateuch, whereas the Aggadic Midrashim have a much larger range, employing the Bible to explore extralegal issues of religious and ethical meaning. The most widely studied Aggadic Midrashim are the Midrash Rabbah ("The Great Midrash"), compiled in the tenth century by Rabbi David ben Aaron of Yemen, and the Midrash of Rabbi Tanhuma in the fourth century. Aggadic Midrashim were written until the thirteenth century, when they yielded to two new genres of sacred writings, philosophy and mysticism (Kabbalah).

The most widely studied Jewish philosophical work is The Guide of the Perplexed, written by Maimonides at the end of the twelfth century, and the seminal work of the Kabbalah is the Zohar ("Book of Splendor"), from the late thirteenth century. Written in form of a mystical Midrash, the Zohar purports to present the revelations of the mysteries of the upper worlds granted to the second-century sage Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai and his circle. It is a work of unbridled imagination and symbolism that exercised a profound impact on the spiritual land-scape of Judaism. The Zohar's far-reaching influence was registered in prayers and in such popular movements as Hasidism (the pious ones), which arose in eighteenth-century Poland and which produced hundreds of mystical teachings and tales, all of which are considered to illuminate divine truths and hence are regarded as sacred.

Websites and Resources: Bible and Biblical History: Bible Gateway and the New International Version (NIV) of The Bible biblegateway.com ; King James Version of the Bible gutenberg.org/ebooks ; Bible History Online bible-history.com ; Biblical Archaeology Society biblicalarchaeology.org ; Judaism Virtual Jewish Library jewishvirtuallibrary.org/index ; Judaism101 jewfaq.org ; torah.org torah.org ; Chabad,org chabad.org/library/bible ; BBC - Religion: Judaism bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/judaism ; Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Torah: The Five Books of Moses, the New Translation” by the Jewish Publication Society Inc. (Editor) Amazon.com ;

“Commentary on the Torah” by Richard Elliott Friedman Amazon.com ;

“The Torah: A Modern Commentary” by Gunther Plaut Amazon.com ;

“JPS Hebrew-English TANAKH” (Hebrew Bible) by Jewish Publication Society Inc. Amazon.com ;

“The Hebrew Bible: A Translation with Commentary” (audiobook) by Robert Alter, Edoardo Ballerini, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Holy Bible in English easy to read version” Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Bible: The Story of the World's Most Influential Book”

by John Barton, Ralph Lister, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Who Wrote the Bible?” by Richard Friedman, Julian Smith, et al.

Amazon.com ;

“The Complete Guide to the Bible” by Stephen M. Miller Amazon.com ;

“The Talmud” by H Polano and Reverend Paul Tice Amazon.com ;

“Everyman's Talmud: The Major Teachings of the Rabbinic Sages” by Abraham Cohen

Amazon.com

Authors of Judaism’s Sacred Texts

Paul Mendes-Flohr wrote in the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: Virtually all of the foundational texts of Judaism, starting with the Hebrew Bible, are of collective authorship. According to Jewish tradition, the first five books of the Bible, known as the Torah, are the Word of God as recorded by Moses. (The exception is the last section, describing his death and burial.) Tradition holds that the other two sections, the Prophets and Writings, were inspired by God, although not directly written by him. Modern critical scholarship, however, regards the Torah as the composite work of several human authors writing in different periods. Similarly, scholarly opinion judges the other books of the Bible to be the work of editors and not necessarily of the authors to whom individual books are ascribed within the texts. [Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Whether one follows the traditional view or that of modern scholars, the Bible is clearly a chorus of many different theological voices. Moreover, not all voices were included in the text as it was finally canonized. Some of these works have been preserved, although not always in the original Hebrew, in what is called the Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha. This literature, which also embraces works written by Jewish authors in Aramaic and Greek, was sanctified in the canons of various Christian churches, often in translation in the sacred language of these churches — for example, Ethiopian, Armenian, Syriac, and Old Slavonic. Indeed, it is only by virtue of the sanctity these books have for Christianity that the voices have been remembered. This body of extracanonical Jewish writings was augmented in 1947 when the manuscripts now known as the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered in caves near the Judean desert.

The voices that came to be a part of the Jewish Scriptures were ultimately determined by the Pharisees, who considered themselves disciples of the scholar and prophet Ezra and who emerged during the time of the Hasmoneans. During this period the dominant voice of the Pharisees was Hillel, known as Hillel the Elder (c. 70 B.C.–c. 10 A.D.). Born and educated in Babylonia, he developed interpretative principles that encouraged a flexible reading of the Torah. Above all, Hillel taught the virtue of Torah study, to be pursued for its own sake and without ulterior motives. He believed that learning, and learning alone, could refine a person's character and religious personality and endow him with the fear of God. It is told that Hillel was once approached by a would-be convert who asked to be taught the whole Torah while Hillel stood on one foot. He replied, "What is hateful to you, do not do unto your fellow human being; this is the whole Torah, all the rest is commentary. Now go and learn!" This, the "golden rule," Hillel suggested, is not only the best introduction to Judaism but also its sum total. Thus, Hillel played a decisive role in the history of Judaism. His hermeneutical rules expanded and revolutionized the Jewish tradition, while his stress on the primacy of ethical conduct and his tolerance and humanity deeply influenced the character and image of Judaism. Hillel was the patron of what has been termed "classical Judaism." To the worship of power and the state, he opposed the ideal of the community of those learned in Torah and of those who love God and their fellow human beings.

Hillel's teachings are woven into the Mishnah, an anthology of Pharisaic interpretations of the Written and Oral Torah that was edited by one of his descendants, Judah ha-Nasi (c. 138–c. 217), head of the Sanhedrin. Noting that over the centuries the Oral Torah had continued to grow exponentially, Judah ha-Nasi deemed it necessary, especially since a majority of Jews by then lived in the Diaspora, to have a written protocol of the most significant teachings. He prevailed upon each of the Pharisees, who bore the honorific title of rabbi (master or teacher of the Torah), to prepare a synopsis of the Oral Torah they taught in the various academies of the Land of Israel. He then edited and collated the material into the compendium titled the Mishnah, a name derived from the Hebrew verb shanah, meaning "to repeat," that is, to recapitulate what one has learned. In his work Judah ha-Nasi had been aided by other scholars who preceded him, in particular Rabbi Akiva (c. 50–c. 136).

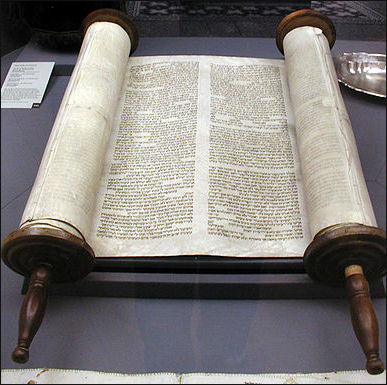

The Torah

an open Torah The Torah is the first part of the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) and equivalent to the first five books of the Christian Bible. The central and most important document of Judaism and used by Jews through the ages, it refers to the five books of Moses which are known in Hebrew as Chameesha Choomshey Torah. The Torah is the equivalent of the Jewish Bible. It is the holiest book in Judaism, the foundation of Christianity and Islam, and the key to all religious thought in Judaism. The term Torah means “to teach,” “guidance and instruction” or "law". It usually refers to the Five Books of Moses (also known as the Pentateuch). Sometimes the term refers to Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) or Old Testament, or even the Old Testament and the Talmud. [Source: BBC, August 13, 2009 |::|]

If the Torah is bound into book form it is called the ‘Chumash’ (which also means ‘five’, just like Pentateuch means ‘five’). The five book are comprised of 1) Bresheit (Genesis), meaning “At the beginning”; 2) Shemot (Exodus), meaning "Names"; 3) Vayicra ("He Called”, Leviticus), 4) Bamidbar ("In the Wilderness.", Numbers), and 5) Devarim ("Words", Deuteronomy). Leviticus is Latin for ‘of the Levites’).

According to traditional Jewish and Christian teachings, the Torah contains the revelation of God, written down by Moses. Jews believe that God dictated the Torah to Moses on Mount Sinai 50 days after their exodus from Egyptian slavery. They believe that the Torah shows how God wants Jews to live. It contains 613 commandments and Jews refer to the ten best known of these as the ten statements. Modern scholars say The Torah was put together from a collection of writings from different authors and sources over hundreds of years. The Torah begins with the creation of the world and ends with Moses’ death. The names of the five books of the Torah are derived from the first unique word that appears in the book.

See Separate Article: THE TORAH africame.factsanddetails.com

Tanakh (Hebrew Bible)

The Torah consists of first five books of the 39-book "Hebrew Bible". "Jewish Bible" or the Tanakh (also spelled Tanach and Tanak). The Hebrew Bible is divided into three parts — The Law (Torah), the Writings (Ketuviym) and the Prophets (Navi'im). The word Tanakh is derived from the first letters of each of the three divisions of the Hebrew Bible. [Source: Jeff Benner, Quora.com, Biblical Hebrew scholar, 2017]

The original Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) was translated into Greek between the 3rd and 1st centuries B.C.. This translation is called the Septuagint (or LXX, both 70 in Latin), because there is a tradition that seventy Jewish scribes compiled it in Alexandria. It was quoted in the New Testament and is found bound together with the New Testament in the 4th and 5th century Greek uncial codices Sinaiticus, Alexandrinus and Vaticanus.

The Septuagint included books, called the Apocrypha or Deuterocanonical by Christians, which were later not accepted into the Jewish canon of sacred writings. Apocrypha in the Old Testament often refers to books included in the Septuagint (Greek translation used by early Christians) and Catholic (including the Latin Vulgate) versions of the Bible but not in Protestant or modern Jewish editions

Most of the books in the Tankh were written in Hebrew between 1200 and 100 B.C. The Protestant Old Testament contains all the same books as the Tanakh (39-Book Jewish Bible) but the books are not in the same order and some books are given more weight than others. Gold Hunter posted on Quora.com: As far as I can tell, Christians give pretty much equal authority (‘word of God’) to ALL the books of the Jewish Bible, and — honestly — Jews don’t. We divide the books of the Jewish Bible into three major sections, and only one of them is ‘word of God’. The second is ‘contains a message from God’ but filtered through people, and the third isn’t really ‘word of God’ at all, but just consists of useful, interesting or inspiring literary works. Okay? That’s a big difference right there. [Source: Gold Hunter, Quora.com, 2023]

Codex Sassoon — the Oldest- Known Hebrew Bible

The oldest known near-complete Hebrew Bible is the Codex Sassoon, one of only two codices, or manuscripts, containing all 24 books of the Hebrew Bible It is — the Christian Old Testament — to have survived into the modern era and is estimated to be 1,100 years old. According to Sotheby's, the Codex Sassoon is significantly more complete than the Aleppo Codex, dated to the same era. [Source: Alexandra Vardi, AFP, March 22, 2023]

Sharon Mintz, a specialist in Jewish texts at Sotheby's, told AFP that carbon dating and other forms of analysis showed the Codex Sassoon "was written around the year 900, either in the land of Israel or Syria". A deed shows the book was sold in 1000 AD, and the codex was then held in a synagogue in what is now northeastern Syria until around 1400, she said. "The manuscript then disappears for about 500 years, and re-emerges in 1929 when it was offered for sale to David Solomon Sassoon, one of the greatest collectors of Hebrew manuscripts."

According to AFP: The manuscript bridges the Dead Sea Scrolls — which date back as early as the third century B.C. — and today's standard texts of the Hebrew Bible, which are based on the work of Greek translators or early mediaeval Jewish scribes. "What you see here is an accurate, stabilised standard text of the Hebrew Bible, written over 1,000 years ago, as accurate as it is today," Mintz said. "It presents to us the first time an almost-complete book of the Hebrew Bible appears with the vowel points, the cantillation and the notes on the bottom telling scribes how the correct text should be written."

The Codex Sassoon bears a cultural significance beyond its linguistic and historic value, said Orit Shaham Gover, curator of the ANU Museum of the Jewish People in Tel Avi. "The Bible plays a central role for any person with even a fleeting connection to Western culture, and this is the first Bible that survived history," she said.

The ANU Museum displayed the Codex. Gover told AFP it was "rare and moving", since it is only the second time in modern history that the codex will be on public display — and the first in Israel. "The Bible wandered in all kinds of places throughout history, and was displayed only once to the public in 1982 at the British Library, and since then was always in private hands," she said. "The Bible is the foundation of Jewish culture," she said.

In May 2023, the Codex Sassoon sold for $38 million at a Sothbey’s auction in New York. It was purchased by the former US ambassador to Romania Alfred H Moses on behalf of the American Friends of ANU and donated to ANU Museum, where it will join the collection, Sotheby’s said in statement. Sotheby's pre-sale estimates put the manuscript's value at between $30 million and $50 million.[Source: Associated Press, May 18, 2023]

Pentateuch — The Torah and the First Five Books of the Tanakh

The Pentateuch refers the First Five Books of the Tanakh, which is also The Torah, and the first five books of the Bible and Old Testament. "Penta" means five in Greek. The word “Pentateuch” is derived from the Greek word pentateuchos, which means “five-volume work.”

The Five Books of the Torah (Law, or Instructions) and the first five books of the Tanakh are: 1) Genesis (Bereshit),is named for the Hebrew word for “in the beginning.” Itt describes the creation of the world, the birth of Adam and Eve, the fall of mankind, and the generations of Adam, including Noah and Cain and Abel. It ends with Joseph’s sale into slavery in Egypt. 2) Exodus (Shemot) narrates the story of the Israelites’ suffering in Egypt, their liberation by Moses, their journey to Mount Sinai, and their wanderings in the wilderness. 3) Leviticus (Vayikrah) focuses mainly on priestly matters, offering instructions for rituals, sacrifices, and atonement, but not on the history of the Jewish people. 4) Numbers (Bamidbar) depicts the wanderings of Israelites in the wilderness as they journey toward the promised land in Canaan. 5) Deuteronomy (Devarim).narrates the end of the journey and ends with Moses’ death just before they enter the promised land.

The five books of the Pentateuch were named by the Jews of Palestine according to the opening Hebrew words: 1) Bereshith: "in the Beginning" 2) We'elleh Shemoth: "And these are the names" 3) Wayyiqra': "And he called" 4) Wayyedabber: "And he spoke" 5) Elleh Haddebarim: "These are the words" [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

Prophets (Nevi’im) — The Second Part of the Tanakh

The Prophets is a group of historical books and books by/about various prophets — like Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel etc. Most of those existed originally as separate scrolls, except the 12 really short books, which were written on one scroll. The Prophets are considered ‘inspired by’ God, but not quite as directly as Torah. Whenever something in Prophets appears to be different from something in Torah, the Torah is ‘correct’ and we are to interpret the Prophet’s words in light of Torah... . [Source: Gold Hunter, Quora.com, 2023]

‘Nevi’im’ doesn’t mean ‘someone who predicts the future’. To Jews, it means ‘someone who delivers a message from God’ to the current generation, using their own words. The prophets in Prophets received messages from God in dreams and visions, and the prophets interpreted these visions themselves, and wrote about them in their own words. These books were written by people, and as such should not be viewed as a word for word message from God. It is a record of the main ideas of what was conveying to them.

The best known parts of The Prophets are Joshua, Judges, I Samuel, II Samuel, I Kings, II Kings, Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel. The Twelve Minor Prophets are Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habukkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi.

All the books called I and II are usually one book in the Tanakh, but each of them is pretty long, and once someone conveniently divided them into two parts, we have mostly gone along with that) NONE of these books were ORIGINALLY divided into ‘chapter and verse’. Christians started doing that with their Bible sometime in the Middle Ages and Jewish communities followed shortly after — this was about the time printing was invented, and the chapter/verse divisions made looking for passages much simpler.

Writings (Ketuvim) — The Third Part of the Tanakh

The Ketuvim (Writings) is a group of generally unrelated written works, from various times and written for various reasons. Nothing in Ketuvim merits designation as ‘word of God’ and most of these books are used a liturgical readings for specific holidays, or for personal edification. It is probably best to call them all ‘inspiring literary works’ rather than inspired anything. are what you might call ‘inspiring literature’ and those books are very diverse: Psalms, Proverbs, Ruth, Esther, Daniel, Lamentations, Song of Solomon, and Chronicles — narratives, poetry, wisdom literature, ‘special event’ works.. [Source: Gold Hunter, Quora.com, 2023]

The writings. This comprises Psalms, Proverbs, Job, Daniel, Ezra, Chronicles, Song of Solomon, Ecclesiastes, Lamentations, Esther, and Ruth. These books were written with divine inspiration, and are not prophetic at all. They are books of wisdom and history.

The Writings include: 1) Psalms, (a book of hymns and songs); 2) Proverbs, (‘wisdom literature’); 3) Job, (a play in parts, and quite old. Job is, for instance, not Jewish); 4) Song of Songs, (more erotic than most people want to admit); 5) Ruth, (read for the holiday of Shavuot (‘Pentecost’)); 6) Lamentations, (read for the fast of Tisha B’Av — anniversary of the destruction of the Temple); 7) Ecclesiastes, (read during the holiday of Sukkot, aka ‘the Feast of Booths’) and 8) Esther (some Christian OTs have additions to Esther) (read for the holiday of Purim)

Daniel is the latest book included in the Jewish Bible. It is is ‘young’ enough to include a few Greek borrow words, placing its composition sometime after Alexander the Great, although it is set at least 200 years earlier.Daniel is popular in kindergarten classes. Mmost Jewish scholars say that if Daniel is a prophecy of the future, then nobody will understand it until Judgement Day arrives. Some Christian OTs have additions to Daniel.

Ezra and Nehemiah are (historical accounts of the return of the Jewish people from Babylonian exile to Jerusalem, and the rebuilding of the Temple there, and the re-establishment of local (theocratic) control — though under the authority of the Babylonian/Persian empire). Good reading. Nehemiah is a very interesting character.

I Chronicles, and II Chronicles. (aka ‘Chronicles of the Kings’) covers some of the same territory as — Kings. But Chronicles has a strong and obvious bias toward religious interpretation of everything (‘this happened because xyz pleased/displeased the Lord’) and we put it in Writings instead of Prophets.

Talmud

Talmud The second most important document in Judaism after the Torah is the “Talmud” , a collection of Jewish laws, traditions, poems, anecdotes, biographies, prophecies and rabbinical interpretations of scriptures and commentaries. The Talmud is divided into the “Mishna” (text) and the “Gemara” (commentary about the “Mishna”). The Talmud is primarily a collection of interpretations of the Torah and a record of the oral tradition of the Jews. The codification that led to the Talmud was done to avoid the dissolution of Judaism by providing laws and guidance for situations not addressed in the Torah.

According to the BBC: “The Talmud is the comprehensive written version of the Jewish oral law and the subsequent commentaries on it. It originates from the 2nd century CE. The word Talmud is derived from the Hebrew verb 'to teach', which can also be expressed as the verb 'to learn'. The Talmud is the source from which the code of Jewish Halakhah (law) is derived. It is made up of the Mishnah and the Gemara. The Mishnah is the original written version of the oral law and the Gemara is the record of the rabbinic discussions following this writing down. It includes their differences of view. The Talmud can also be known by the name Shas. This is a Hebrew abbreviation for the expression Shishah Sedarim or the six orders of the Mishnah.” [Source: BBC, August 13, 2009 |::|] The Talmud can derives an extraordinary number of laws and ideas from a simple sentence or phrase. Kosher food is a good example of how the Talmud derives an extraordinary number of laws and ideas from a simple sentence or phrase. The sentence “Thou shall not eat anything with the blood” (Leviticus xix 26) is taken to mean that one can not eat: 1) any animal that still has life in it; 2) any animal parts that still have blood in them; 3) before one prays for pure life (based on the connection of blood with life); 4) sacrificial meat while blood is still in the basin; 5) on the day a judge gives out a death sentence. Connected with the prohibition is warning that gluttony will lead one down the road to ruin.

The Mishnah (original oral law written down) is divided into six parts which are called Sedarim, the Hebrew word for order (s).

1) Zera'im (Seeds), is about the laws on agriculture, prayer, and tithes

2) Mo'ed (Festival), is about the sabbath and the festivals

3) Nashim (Women), is about marriage, divorce and contracts – oaths

4) Nezikin (Damages), is about the civil and criminal laws, the way courts operate and some further laws on oaths

5) Kodashim (Holy Things), is about sacrificing and the laws of the Temple and the dietary laws

6) Toharot (Purities), is about the laws of ritual purity and impurity.

History of the Talmud

As important as the Torah is, the thing that marked the true creation of Rabbinic Judaism was the creation of the Talmud. Also known as the Gemara, the Talmud is a running commentary on The Torah written by rabbis (called amoraim, or "explainers") from the third to the fifth centuries A.D. in Palestine and Babylonia. The work of the former is called the Jerusalem Talmud and the latter the Babylonian Talmud, which is generally regarded as the more authoritative of the two

The Mishnah: is the written text of the Talmud.. The Midrash is commentary on the Scriptures, both Halakhic (legal) and Aggadic (narrative), originally in the form of sermons or lectures The Aggadah nonlegal, narrative portions of the Talmud and Mishna, includes history, folklore, and other subjects. The Halakhah legal portions of the Talmud as later elaborated in rabbinic literature; in an extended sense it denotes the ritual and legal prescriptions governing the traditional Jewish way of life

The Talmud took 500 years to put together. It began as a set of oral laws, interpretations of the Torah and applications of Torah to new situations. Around A.D. 200, these laws were written down by Rabbi Judah ha Nasi. This became the Mishna. For the next 200 years these interpretation were debated and updated. This resulted in the Gemara. Around A.D. 500 the Mishna and the Gemara were further updated and combined by the Babylonian Rabbi Rav Ashi. This became the Talmud.

Over time several Talmuds were written. Many passages were written in Aramaic, the language of Jesus. The main ones are the Palestinian version and Babylonian version complied by Rav Ashi. The first — the Palestinian, or Jerusalem, Talmud —was finalized around the A.D. 3rd century in Palestine. The second — the more authoritative and superior Babylonian Talmud — was completed during the A.D. 5th century in Babylon. These were later organized into summaries to help readers understand them better. The most well known of these are the code of Maimonides (1135-1204) and Joseph Caro (1488-1575), known as “Shulchan Aruch” .

According to the BBC: Between the 2nd and 5th centuries CE rabbinic discussions about the Mishnah were recorded in Jerusalem and later in Babylon (now Al Hillah in Iraq). This record was complete by the 5th Century CE. When the Talmud is mentioned without further clarification it is usually understood to refer to the Babylonian version which is regarded as having most authority. The rabbi most closely associated with the compilation of the Mishnah is Rabbi Judah Ha-Nasi (approx. 135-219 CE). During his lifetime there were various rebellions against Roman rule in Palestine. This resulted in huge loss of life and the destruction of many of the Yeshivot (institutions for the study of the Torah) in the country. This may have led him to be concerned that the traditional telling of the law from rabbi to student was compromised and may have been part of his motivation for undertaking the task of writing it down. [Source: BBC, August 13, 2009 |::|]

Creation of the Talmud

J.M Oesterreicher wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: At the turn of the 1st Christian century, Rabbi Judah ha-Nasi, then head of the Great Bet Din, gathered the oral traditions and probably had them put into writing. The compilation was named mishnah for the method applied, i.e., repetition; it contained the important halakic (legal) teachings of the preceding generations of rabbis, the Tannaim, or traditioners. The Mishnah soon became the standard work of study and investigation in the academies of Palestine and Babylon. The men who commented on it, the Amoraim, or expositors, produced the gemarah, or completion. [Source: J.M Oesterreicher, New Catholic Encyclopedia, 1960s, Encyclopedia.com]

Both, Mishnah and Gemarah, make up the Talmud, which is, therefore, basically halakic. Haggadic material, however (see haggadah), i.e., spiritual and moral reflections, together with practical counsels, metaphysical speculations, historical narratives, legends, scientific observations, etc., appear in it as well. The Talmud was completed at the end of the 4th century in Galilee and a century later in Babylonia; hence the two versions, the Palestinian and the Babylonian Talmuds. The Talmud is not the only compilation of rabbinic thought. There are, e.g., collections of haggadic commentaries on the Biblical books, the Midrashim.

According to the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: In the Land of Israel and in Babylonia scholars known as amoraim (Aramaic for "explainers") organized themselves into academies (yeshivas) to study the Mishnah and other collections of rabbinical teachings. The record of the reflections and debates of the amoraim was published as a commentary on the Mishnah in two multivolume works, the Jerusalem and the Babylonian Talmuds. Both encompass the work of many generations of scholars. The Jerusalem Talmud, actually composed in academies in Galilee, was concluded in about 400, and the Babylonian Talmud a century later. Because of the intensification of the anti-Jewish policy of the Roman authorities, which led to the flight of many scholars, the Jerusalem Talmud was hastily compiled. It thus lacks the editorial polish of the Babylonian Talmud, which was prepared under far calmer circumstances.[Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

The amoraim also edited collections of the commentaries known as Midrashim. Whereas previous collections had been based on Halakhic (legal) discussions of the rabbis of the Land of Israel, the later Midrashim, edited in the fifth and sixth centuries, largely originated in the homilies of synagogues, which had become the central institution of Jewish religious life. These Midrashim were also devoted to an exegesis of Scripture, often in a sustained line-by-line commentary. There are, for example, such collections for the books of Genesis, Lamentations, Esther, the Song of Songs, and Ruth.

Complexity, Vaugeness and Confusion in The Talmud

J.M Oesterreicher wrote in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: What makes the understanding of the Talmud difficult is that it is a code of laws, a case book, and a digest of discussions and disputes that went on among various rabbis; interspersed are reflections of every kind; its contents are at times as motley as a daily newspaper. Now and then the opinions recorded are dissimilar or even contradictory. Quite often, the rabbis consider a man ignorant of the Law unworthy of trust, unreliable as witness in a court, unfit to be an orphan's protector. Yet the compilers of the Talmud rejoice in telling of the power a simple man has in heaven.

During a drought, Honi (1st century B.C.) drew a circle around himself and said to God, "I swear by Your great name that I will not budge from here until You have mercy upon Your children," and rain fell (Ta’an. 23a). Moreover, the Talmud engages in a great deal of casuistry, and all casuistry tends to be tortured; still, in admonishing its readers not to wrong another man through words, it calls moral demands that cannot be codified "things entrusted to the heart" (Bava Metzia 58b). [Source: J.M Oesterreicher, New Catholic Encyclopedia, 1960s, Encyclopedia.com]

So great is the occasional contrast between rabbinical statements that, in one place, it can be said that the nations' charity is but sin since they practice it for no other reason than to boast; in another, that the Holy Spirit rests on a man, be he Gentile or Jew, according to his deeds. Many rabbinic sayings are, therefore, tentative or are located in a definite situation so that evaluation of rabbinic thought is a special science, indeed, an art. It is not only the variety of opinions recorded in the Talmud and other rabbinical literature that hamper their appreciation, but also the style — succinct, telegraphic, often bare to the bone — makes the Talmud inaccessible without a guide. Such guidance was provided by the heads of the two leading rabbinic academies of Babylonia, titled Geonim, "illustrious ones." From the 6th to the 11th centuries their authority was supreme all over Babylonia — which in the meantime had become the center of all Jewry — and thus, for most of that time, in other countries as well. Yet at the very moment the rule of talmudic Judaism seemed unassailable, it was contested by the Karaites, schismatics who, in the 8th century, repudiated the entire rabbinic tradition.

Additions and Commentaries of the Talmud

Eliezer Segal of the University of Calgary wrote: “The page format of the Babylonian Talmud has remained almost unchanged since the early printings in Italy. Some twenty-five individual tractates were printed by Joshua and Gershom Soncino between 1484 and 1519, culminating in the complete edition of the Talmud produced by Daniel Bomberg (a Christian) in 1520-30. These editions established the familiar format of placing the original text in square formal letters the centre of the page, surrounded by the commentaries of Rashi and Tosafot, which are printed in a semi-cursive typeface. The page divisions used in the Bomberg edition have been used by all subsequent editions of the Talmud until the present day. [Eliezer Segal, University of Calgary]

“Over the years several additions were introduced, including identifications of Biblical quotes, cross-references the Talmud and Rabbinic literature, and to the principal codes of Jewish law. Almost all Talmuds in current use are copies of the famous Vilna (Wilno, Vilnyus) Talmuds, published in several versions from 1880 by the "Widow and Brothers Romm" in that renowned Lithuanian centre of Jewish scholarship. While retaining the same format and pagination as the previous editions, the Vilna Talmud added several new commentaries, along the margins and in supplementary pages at the ends of the respective volumes.

According to the BBC: “In addition to the Talmud there have been important commentaries written about it. The most notable of these are by Rabbi Shelomo Yitzchaki from Northern France and by Rabbi Moses Maimonedes from Cordoba in Spain. They lived in the 11th and 12th centuries respectively. Both of these men have come to be known to Jews by acronyms based on their names. These are respectively Rashi and Rambam. Rambam compiled the Mishneh Torah which is a further distillation of the code of Jewish Law and has come to be regarded by some as a primary source in its own right. |::|

“It is also worth mentioning another codifying work from the middle ages. This is the Shulcan Aruch (laid table) by Joseph Caro which is widely referenced by Jews. Some Orthodox Jews make it part of their practise to study a page of the Talmud every single day. This is known as Daf Yomi which is the Hebrew expression for page of the day. The tradition began after the first international congress of the Agudath Yisrael World Movement in August, 1923. It was put forward as a means of bringing Jewish people together. It was suggested by Rav Meir Shapiro who was the rav of Lublin in Poland.” |::|

Mishna, Gemara and Prayer Books

The “Mishnah “ was an attempt to synthesize, summarize and systematize the customs, concepts and laws of the Jewish people. It consists primarily of a systematic collection of legal decisions based on interpretation of the Torah. It is comprised of six subjects (orders): Seeds, Festivals, Women, Damages, Sacred Things and Cleanness. The Gemara is an unordered collection of arguments and opinions on the law and miscellaneous material. Points are often made with parables, stories, poems prayers and anecdotes. There are also sections on mathematics and science. The Midrashim are stories and homilies told by the sages to led understanding to commentary and halacha (laws) that have evolved over 2000 years. They are regarded as less authoritative than the Talmud.

Another important work of collective authorship that emerged during Talmud period was the Hebrew prayer book, which with local variations became authoritative for Jews everywhere. For centuries prayers were memorized and passed down from generation to generation. Prayer books were not introduced until around the 9th century. Modern prayer books — which include the “Siddar” (daily prayers) and the “Mahazar” (festival prayers) — generally are printed in Hebrew on one page and have a translation on the facing page. Many of these prayers are taken from the psalms. One of the most important is the Hebrew blessing of the Sabbath candles. These days, many Jews don’t know the words.

Paul Mendes-Flohr wrote in the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices Although the Bible gives witness to personal prayers, it is not clear that Temple rituals were accompanied by communal prayers. Sacrificial rites were accompanied by a chorus of psalms chanted by Levites (descendants of Levi, the third son of Jacob, who were by hereditary privilege assigned a special role in the Temple service) but without the participation of the congregation. There is evidence, however, that in the Second Temple a form of communal prayer had begun to take shape. But it was only after the destruction of the Temple and the end of its rites that the rabbis at Jabneh began to standardize Jewish liturgical practice. Alongside the obligatory prayers instituted by the rabbis, there also developed the tradition of composing piyyutim (liturgical poems), many of which were incorporated into the prayer book. [Source:Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024