Home | Category: Christian and Jewish Groups / Jewish Groups in the Middle East and North Africa

JEWS IN NORTH AFRICA

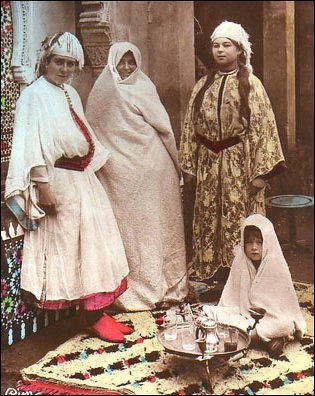

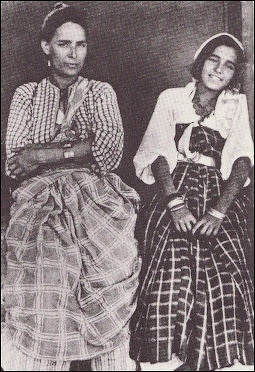

Jewish women and children in Meknes

Morocco and Tunisia are the only Arab countries in which Judaism has remained alive and are the only countries in the Arab world that have significant populations of Jews. There are 3,500 to 5,000 Jews in Morocco. There used to be a lot more.

Judaism has a 2,000 year history in the Maghreb. The first Jews arrived in the region after the Jews were forced out of Palestine by the Romans after the destruction of the Temple in A.D. 70. Many people had converted to Judaism before the arrival of Islam and remained Jewish after it came.

Jews in the Middle East and North Africa

Country or Territory — Core Jewish Population — Population per Jewish Person — Enlarged Jewish Population [Source: Wikipedia +]

Israel — 6,399,000 — 1.32 — 6,451,000

Turkey — 17,200 — 4,801 — 21,000

Iran — 8,756 — 9,186 — 12,000

Morocco — 6,000 — 13,745 — 6,500

Tunisia — 900 — 12,153 — 1,100

Lebanon — 200 — 29,415 — 200

United Arab Emirates — 100 — 91,570 — 500

Yemen — 40 - 50 — 289,467 — 300

Egypt — 18 — 5,259,277 — 40 - 50

Bahrain — 36 36,500 — 36

Websites and Resources: Virtual Jewish Library jewishvirtuallibrary.org/index ; Judaism101 jewfaq.org ; BBC - Religion: Judaism bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/judaism ; Yivo Institute of Jewish Research yivoinstitute.org ; Jewish History: Jewish History Timeline jewishhistory.org.il/history Jewish History Resource Center dinur.org ; Center for Jewish History cjh.org ; Jewish History.org jewishhistory.org ; Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Story of the Jews” Volume One: Finding the Words 1000 BC-1492 AD by Simon Schama (Author) Amazon.com ;

“The Story of the Jews Volume Two: Belonging: 1492-1900 by Simon Schama Amazon.com ;

“Exploring Sephardic Customs and Traditions” by Marc Angel Amazon.com ;

“Foundations of Sephardic Spirituality: The Inner Life of Jews of the Ottoman Empire”

by Rabbi Marc D. Angel Amazon.com ;

““The Ashkenazic Jews: A Slavo-Turkic People in Search of a Jewish Identity” by Paul Wexler Amazon.com ;

““The Origin of Ashkenazi Jewry: The Controversy Unraveled” by Jits van Straten

Amazon.com ;

““The Destruction of the European Jews” by Raul Hilberg Amazon.com ;

“The Lost World of Russia's Jews: Ethnography and Folklore in the Pale of Settlement” by Abraham Rechtman, Nathaniel Deutsch , et al. Amazon.com ;

“Living a Jewish Life: Jewish Traditions, Customs, and Values for Today's Families” by Anita Diamant, Howard Cooper, et al. Amazon.com ;

href="https://amzn.to/3wsGp4G"> Amazon.com ;

“To Be a Jew Today: A New Guide to God, Israel, and the Jewish People”

by Noah Feldman Amazon.com ;

“Essential Judaism: Updated Edition: A Complete Guide to Beliefs, Customs & Rituals”

by George Robinson Amazon.com ;

“Judaism: History, Belief and Practice” by Dan Cohn-Sherbok Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jews” by Paul Johnson, Amazon.com

Early History of the Jews in North Africa

Under the Ptolemies (305-30 B.C.), Cyrenaica (coastal Libya) had become the home of a large Jewish community, whose numbers were substantially increased by tens of thousands of Jews deported there after the failure of the rebellion against Roman rule in Palestine and the destruction of Jerusalem in A.D. 70. The towns of Roman North Africa had a substantial Jewish population. Some Jews were deported from Palestine in the first and second centuries A.D. for rebelling against Roman rule; others had come earlier with Punic settlers. In addition, a number of Berber tribes had converted to Judaism.*

Berber Jews

Some Jewish refugees from Palestine made their way into the desert, where they became nomads and nurtured their fierce hatred of Rome. They converted to Judaism many of the Berbers with whom they mingled, and in some cases whole tribes were identified as Jewish. In 115 the Jews raised a major revolt in Cyrenaica that quickly spread through Egypt back to Palestine. The uprising was put down by 118, but only after Jewish insurgents had laid waste to Cyrenaica and sacked the city of Cyrene. Contemporary observers counted the loss of life during those years at more than 200,000, and at least a century was required to restore Cyrenaica to the order and prosperity that had meanwhile prevailed in Tripolitania.*

By the beginning of the second century, Christianity had been introduced among the Jewish community, and it soon gained converts in the towns and among slaves. An invasion of Muslim Arabs from Saudi Arabia and the Middle East brought Islam to region. However the Islamization and arabization of the region were complicated and lengthy processes. Whereas nomadic Berbers were quick to convert and assist the Arab invaders, not until the twelfth century under the Almohad Dynasty did the Christian and Jewish communities become totally marginalized.*

Later History of the Jews in North Africa

After the Arab conquest, North Africa was governed by a succession of amirs (commanders) who were subordinate to the caliph in Damascus and, after 750, in Baghdad. In 800 the Abbasid caliph Harun ar Rashid appointed as amir Ibrahim ibn Aghlab, who established a hereditary dynasty at Kairouan that ruled Ifriqiya and Tripolitania as an autonomous state that was subject to the caliph's spiritual jurisdiction and that nominally recognized him as its political suzerain. The Aghlabid amirs repaired the neglected Roman irrigation system, rebuilding the region's prosperity and restoring the vitality of its cities and towns with the agricultural surplus that was produced.

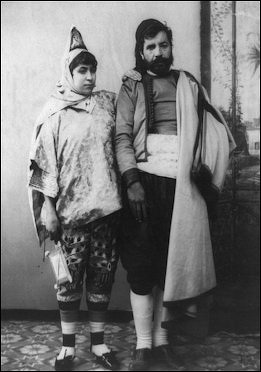

Maghrebi Sephardic Jews in 1919

At the top of the political and social hierarchy were the bureaucracy, the military caste, and an Arab urban elite that included merchants, scholars, and government officials who had come to Kairouan, Tunis, and Tripoli from many parts of the Islamic world. Members of the large Jewish communities that also resided in those cities held office under the amirs and engaged in commerce and the crafts. Converts to Islam often retained the positions of authority held traditionally by their families or class in Roman Africa, but a dwindling, Latinspeaking , Christian community lingered on in the towns until the eleventh century. The Aghlabids contested control of the central Mediterranean with the Byzantine Empire and, after conquering Sicily, played an active role in the internal politics of Italy.*

The final triumph of the 700-year Christian reconquest of Spain, marked by the fall of Granada in 1492, was accompanied by the forced conversion of Spanish Muslims (Moriscos). As a result of the Inquisition, thousands of Jews fled or were deported to the Maghrib, where many gained influence in government and commerce. Jews and moriscos, descendants of Muslims expelled from Spain in the sixteenth century, were active as merchants and craftsmen, some of the moriscos also achieving notoriety as pirates. *

During the French colonial period (1830-1962) laws covering secular matters reflected Western influence in general and the Napoleonic Code in particular. Non-Muslims were not under sharia. For example, the Jewish minority was subject to its own religious courts. Europeans were subject to their national laws through consular courts, the European nations having secured capitulary rights from the Turks.*

Jews in Morocco

There are about 6,000 Jews in Morocco. There used to be a lot more. Most Moroccan Jews live in Casablanca. The community is stable but aging. It runs its six synagogues, Jewish schools, six kosher restaurants, a kosher liquor store and butchers and bakeries. Yom Kippur services have been broadcast on Moroccan television. In an effort to keep the community robust a new synagogue and Jewish museum were opened in 2002.

Jews in Fex

More than a million Moroccan Jews live abroad. More than 700,000 million of them live in Israel. These Jews have had strong impact on Israeli culture by infusing folk religion into Judhism, giving it an Oriental-Jewish flavor, reflecting in part the demographic preponderance of Oriental Jews since the 1970s. Such customs include ethnic festivals such as the Moroccan mimouna — an annual festival of Moroccan Jews, originally a minor holiday in Morocco, which has become in Israel a major celebration of Moroccan Jewish ethnic identity.

At the end of the World War II, Jews made up 250,000 of the 7 million people in Morocco. Some left for Israel when it became a nation in 1948. Most left in 1956 after Morocco became independent. Even though Mohammed V assured the Jews’ safety many of them feared anti-Semitic hostility.

Of the 17,000 Jews that once lived in Fez only about 450 are left. Of the 6000 Jews that lived in the Mellah of Marrakesh only 70 or so remain. The others mostly moved to Israel. There is still a large Jewish community in Casablanca.

History of Jews in Morocco

Morocco has a long history of liberalism and tolerance. It accepted the Jews expelled from Spain in the 1490s; was one of the first nations to recognize the United States after the American Revolutionary War; was the first Arab nation to give women the right to vote; and was the first Arab nation to recognize Israel after the 1993 peace accord was signed with the Palestinians.

Many Sephardic Jews made their homes in Morocco after the were expelled from Spain in the 1490s. Many of the Jews that lived in Morocco until fairly recently traced their origin back to Jews who arrived in Morocco during this period. One reason the Jews have prospered in Morocco is that it has been a place where Berbers and Arabs shaped the history and multi-culturalism has been a fixture of everyday life for a long time. One Moroccan Jewish businessman told the Los Angeles Times, “If you look at historically, it’s better to have been a Jew in Morocco than in Europe.”

In the old days, the bureaucracy demanded palm-greasing to get the most rudimentary things done and even demanded protection money. Jewish groups were forced to operate under Muslim “umbrellas.” The Jews endured and some prospered during the French colonial period but when the French left there were only 17 Jewish and 19 Muslim doctors and 15 Jewish and 15 Muslim engineers in Morocco.

Moroccan Kings and Moroccan Jews

Andre Azoulay

Because he was descendant of the prophet, King Hassan felt he had special responsibility preserving the Islamic character of Jerusalem while at the same time having discreet relations with Israel and the Jews with Morocco roots. For centuries Jews in Fez and other Moroccan cities lived in special quarters by the king's palace. Many were scholars and one was evan a vizier to the sultan

During World War II, King Mohammed V protected Jews living in the country from the Nazis. The Vichy French government ordered the Jews to move to France. King Mohammed refused to go along with the order and said, “I will wear the first star because all Moroccans are my children.”

One of King Hassan’s closet advisors, Andre Azoulay, was a Jewish banker who worked in Paris for many years. The former Minister of Tourism was Jewish. The United States ambassador to Morocco for many years, Marc Ginsberg, was a Jew who grew up in Israel. He has been the only Jewish ambassador to have served in an Arab country since the birth of Israel.

Discrimination, Anti-Semitism and Terrorism Directed Towards Jews in Morocco

For centuries Jews were restricted to living in ghettos. Until 1912, the weren’t allowed to wear shoes outside the ghettos walls. There has been stabbings of Jews in modern times. The Jewish graves outside Fez are embedded in a single concrete foundation to prevent desecration. Andre Azoulay, the last powerful Jewish politician in an Arab country, was sacked after Islamist demonstrations. A member of an Islamic group told the Economist; “Jews sympathize with Israel; they can not be trusted with the affairs of a Muslim state.”

On May 16, 2003, a cell of Islamist terrorists belonging to a group calling itself Salafiya Jihadiya bombed a series of Jewish targets in Casablanca; 45 people, including 12 suicide bombers, died in the incidents. The series of explosions injured more than 100 people. Casablanca is believed to have been selected as a target because it is one of the few places left in the Arab world with a sizable Jewish community. The bombing occurred just four days after another terrorist attack in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia that left 34 people dead. Al-Qaida is believed to have had a hand in both the attacks. They both occurred after a tape by Osama bin Laden was played on Arab televison in which both Morocco and Saudi Arabia were listed as “apostate” Arab nations.

There were five separate explosions that occurred within 20 minutes of one another. Three of the targets were aimed at Jews. No Jews were killed. One explosion occurred at a Jewish community center. Another occurred at a Spanish club, where 18 people died. The others were at the Hotel Farrah, a Jewish-owned restaurant and a public fountain near a Jewish cemetery. Eleven of the dead were suicide bombers. Most of the victims were Muslim Moroccans. Two of the dead were French. One was Spanish. The attack shattered Morocco’s image as a peaceful, liberal, tolerant Arab nation. The attacks raised concerns by Jews about their safety and how well they could trust the Muslim neighbors.

Algerian Jews

Algeria’s Jewish population is barely a trace of its former presence, reportedly numbering only about 60 persons. The Jewish community is of considerable antiquity, some members claiming descent from immigrants from Palestine at the time of the Romans. The majority are descendants of refugees from Spanish persecution early in the fifteenth century. The cities also had small Jewish communities that would become more important under the French colonial system.

Algerian Jew

The Jews in Algeria numbered about 140,000 before the Algerian revolutionary period, but at independence in 1962 nearly all of them left the country. Because the 1870 Crémieux Decrees, which aimed at assimilating the colons of Algeria to France, gave Jews full citizenship, most member of the Jewish community emigrated to France. [Source: Library of Congress *]

When the Prussians captured Napoleon III at the Battle of Sedan (1870), ending the Second Empire, the colons in Algiers toppled the military government and installed a civilian administration. Meanwhile, in France the government directed one of its ministers, Adolphe Crémieux, "to destroy the military regime . . . [and] to completely assimilate Algeria into France." In October 1870, Crémieux, whose concern with Algerian affairs dated from the time of the Second Republic, issued a series of decrees providing for representation of the Algerian départements in the National Assembly of France and confirming colon control over local administration. A civilian governor general was made responsible to the Ministry of Interior.

The Crémieux Decrees also granted blanket French citizenship to Algerian Jews, who then numbered about 40,000. This act set them apart from Muslims, in whose eyes they were identified thereafter with the colons. The measure had to be enforced, however, over the objections of the colons, who made little distinction between Muslims and Jews. (Automatic citizenship was subsequently extended in 1889 to children of non- French Europeans born in Algeria unless they specifically rejected it.)

Algerian Muslims rallied to the French side at the start of World War II as they had done in World War I. Nazi Germany's quick defeat of France, however, and the establishment of the collaborationist Vichy regime, to which the colons were generally sympathetic, not only increased the difficulties of the Muslims but also posed an ominous threat to the Jews in Algeria. The Algerian administration vigorously enforced the anti-Semitic laws imposed by Vichy, which stripped Algerian Jews of their French citizenship. Potential opposition leaders in both the European and the Muslim communities were arrested.*

Algeria became independent on June 17, 1962. In the same month, more than 350,000 colons left Algeria. Immediately after independence approximately 1 million Europeans, including 140,000 Jews, left the country. Most of the Europeans who left had French citizenship, and all identified with French rather than Arab culture and society. Within a year, 1.4 million refugees, including almost the entire Jewish community and some pro-French Muslims, had joined the exodus to France. Fewer than 30,000 Europeans chose to remain.*

The government of independent Algeria discouraged antiSemitism , and the small remaining Jewish population appeared to have stabilized at roughly 1,000. It was thought to be close to this number in the early 1990s. Although no untoward incidents occurred during the Arab-Israeli wars of 1967 and 1973, a group of youths sacked the only remaining synagogue in Algiers in early 1977.*

Jews in Tunisia

Morocco and Tunisia are the only countries in the Arab world that have significant populations of Jews. There are around 900 Jews in Tunisia. Most live in Tunis or on Jerba Island. There were around 100,000 in 1948 and about 2,500 in the early 2000s.

Tunisian Jews

Many Jews arrived in the region after the Jews were forced out of Palestine by the Romans after the destruction of the Temple in A.D. 70. Many Jews were traders. They introduced monotheism to the pagan Berber trines. Many people who had converted to Judaism before the arrival of Islam and remained Jewish after it came. Jews also arrived after the were expelled from Spain in the Inquisition period, because of Greek persecution and after Sicilian raids in Libya.

Jews say they have traditionally gotten on well with Muslims and say they integrated but were not assimilated. They describe how Muslims bring them bread during the sabbath. Jews like Muslims keep the Hand of Fatima to ward off the Evil Eye. Many send their children to Muslim schools even they can send them to Jewish schools.

But they don’t intermarry with them. Once a Muslim woman on Jerba met a Jewish man and fell in love with him. The man was forced to leave the island while the woman stayed. For a long time, Israeli passport holders could visit Tunisia, something that is unusual in many Arab countries. Tunisian Jews can visit Israel. There have long been telephone links between Israel and Tunisia. Habiba M-Sika was a popular Jewish Tunisian singer in the 1930s. Jakob Cchiri is another popular Jewish musician.

Jerba

Jerba (Djerba, near Zazis) is popular tourist destination in Tunisia. Settled by Phoenicians, it has been inhabited by Jews as early as 586 B.C. and was a recreational place in Roman times and is now occupied mostly by members of the radical Kharijte sect of Islam, who have built more than 200 mosques. It is very popular with package tourists from northern Europe, many of whom explore the island on rented bicycles or mopeds.

Kristen McTighe wrote in USA Today: “Hara Kabira, in the heart of Djerba, is the largest of two Jewish neighborhoods on the island, where schoolboys wear kippas, or skull caps, and women wear scarves to cover their hair, as part of their religion's Orthodox tradition. They speak Arabic and Hebrew, and some know French. Men often work in jewelry shops in Houmt Souk, and women mostly stay home to raise families. [Source: Kristen McTighe, USA TODAY, May 27, 2016]

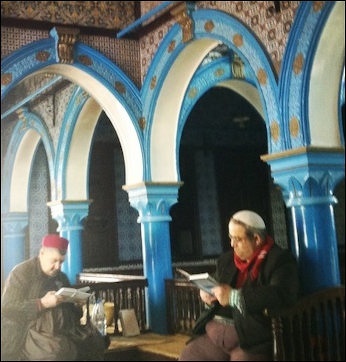

Djerba synagogue

Houmt Souk is the main town on the island. It is a charming place with cafes, open squares, and narrow alleys. A few foundouks (caravanserai) remain from the days when the island was pilgrimage stop and vacation area for caravan merchants. Worth a look are the museum and the Bor el Kabir, a fort built in the 13th century by the Aerogenes and expanded by the Spanish in the 16th century. Other sights on the island include Hara Seghira, a small Jewish town; and Guellala, famous for its pottery.

Jerba can be reached by an ancient Roman causeway. There are also regular ferries between Jorf and Jerba Island. Jewish restaurants on Jerba Island offer couscous royal, made with meatballs and stuffed vegetables. Jerba Island is regarded as one of Tunisia’s best fishing spots. Over 86 species of fish have been caught in its waters. Jerba attracts a large number of European vacationers. It has some very large beach resort hotels, mostly on the northwest coast, with 30,000 beds. Homt Souk is the largest town. It is good place to buy Jewish-made silver jewelry. Jerbans are regarded as shrew merchants. They run many small grocery stores in France and run trading operations in Libya and Algeria.

Jews on Jerba

Jews on Jerba are believed to have settled on the island as early as 586 B.C. They are believed to have fled Palestine after the destruction f the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem. They were traders with connections to the Phoenicians.

About 1,100 Jews live on Jerba. There are regarded as conservative and religious. The don’t drive or use telephone son the Sabbath, speak Hebrew (and Arabic), keep kosher homes, and worship at 14 synagogues. Women don’t work outside the home and take ritual premenstrual baths. About half of them are involved silver jewelry making. Some wear baggy trousers and red felt hats. Some children study at schools that emphasize religion and don’t teach math or science or foreign language because they pollute the mind. They are centered primarily around Ghriba, a very old synagogue. Modern American Jews regard them as biblical.

Around the time of World War II around 20,000 to 40,000 Jews lived on the island. They mostly emigrated to Israel and Europe. Those that have remained said they did so because they already had some money and said they got on well with their Muslim neighbors. They said that those who left did because of the promise of a future in Israel and Europe not because they felt hostility from local Muslims.

synagogue in Ghriba

Kristen McTighe wrote in USA Today: “Jews have been on Djerba for more than 2,000 years, living alongside Muslims and Christians in the center of the Arab world. As violent religious extremism engulfs the region around them, residents on this quiet North African island say they are resolute to stay. “Thanks to God, we can live peacefully and without problems,” said Yousef Oezen, president of the Jewish community in Djerba. “There are marriages, the youth are having children. The Jewish community can live here, and we can grow.”[Source: Kristen McTighe, USA TODAY, May 27, 2016 ~]

While nearly all the Jews that once lived in Arab regions have fled, the Jews of Djerba did not. “The population is about 1,100. nearly half of which are younger than 20, Oezen said. "They live alongside their Muslim neighbors, and they do so very well,” said Valerie Davis Allouche, Tunisia country director for the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, a humanitarian group that works with the community. “Jewish and Muslim kids play together in the streets. They work alongside their neighbors. Co-existence is a working reality.” “We are very secure,” Koudir Hania, the synagogue's manager, said as he locked the doors to the holy site at the end of the day. “Calm, life is calm.” ~

Though relations with Muslims and Christians are amicable, the community remains tightknit and insular — a way to resist assimilation and preserve traditions. “We work together, we talk, we have a coffee, but we go home to our own homes at the end of the day,” Oezen explained. “Everyone has their own religion, we don’t mix these things.” As the Muslim call to prayer echoed across the market on a recent Friday in Houmt Souk, Elia stood behind a jewelry counter and pointed to an employee in the small shop. “I am Jewish, and he is Muslim,” he said. “We have worked together here for years, and our fathers worked together before that. We are very close.” ~

Pilgrimage to Africa’s Oldest Synagogue in Djerba

Gbhiba shrine is North Africa’s oldest synagogue site. The first religious structure was built around the times the Jews arrived in 586 B.C. Set in the middle of an olive grove and built in the 1920s, it is blue and white and ornately tiled. Inside a grotto in the synagogue is a stone said to have flown here from the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem that was destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 B.C. It also contains one of the oldest Torahs in the world. Visitors need to be dressed in hats, scarves and long pants or skirts. After terrorism attacks, a 10-foot-high cement wall was placed around the synagogue.

Gbhiba is the site of the annual Lag B’ Omer pilgrimage in April. It honors the Kabbalah, the Jewish book of mysticism. Pilgrims drink lots of fig liqueur and a participate in a parade in which they carry menorahs and dress in silk scarves. Women place eggs around the stone from Solomon’s Temple. Jews from all over North Africa and the world come.

Djerba (Jerba) is home to Africa's oldest synagogue Describing the annual Jewish pilgrimage there,Kristen McTighe wrote in USA Today: “Despite warnings from Israel to avoid traveling to one of the Arab world's last Jewish communities, thousands came to the ancient El Ghriba synagogue this week to celebrate the Jewish festival of Lag b'Omer. Jews from Tunisia, Europe and elsewhere made the annual two-day pilgrimage that began Wednesday under tight security to mark the holiday with prayers, candles and wishes written on eggs. [Source: Kristen McTighe, USA TODAY, May 27, 2016]

Jewish Pilgrimage to Djerba Under Tight Security

On pilgrimage in 2016, Kristen McTighe wrote in USA Today: “Organizers estimated 2,000 people made the trip here despite a severe warning by Israel’s National Security Council Counter-Terrorism Bureau that recommended all travel to Tunisia be avoided. “Terrorism is everywhere, it’s in Paris, it’s in Bardo. The problem is worldwide,” Lior Elia said in his family jewelry shop in Houmt Souk, the main city on the island of Djerba off the Tunisian coast. “We are protected here, the police work for us and for everyone, and we are also protected, thanks to God.” “We protect each other always,” said Madji Barouni, a Muslim college student who stopped by the shop to visit his friend Elia. [Source: Kristen McTighe, USA TODAY, May 27, 2016 ~]

“There have been plenty of security concerns. In an assault in March, militants affiliated with the Islamic State stormed the Tunisian border town of Ben Gardane, leaving more than 50 dead. Access to Djerba was immediately cut off. Two high-profile attacks last year in Tunisia — at the Bardo National Museum in Tunis and in the beach resort of Sousse — stoked fears that the Jewish community could become a target of extremists. In 2011, the annual pilgrimage to El Ghriba synagogue was canceled amid security concerns. Jewish cemeteries were vandalized, and several anti-Jewish incidents were reported. In 2002, al-Qaeda claimed responsibility for a truck explosion in front of the synagogue that killed nearly two dozen people, mainly German tourists.~

“To reassure Tunisian Jews, Rashid Al-Ghannoushi, leader of Tunisia's Nahda party, recently sent a delegation to Djerba to tell the community it would be protected. The image of tolerance bodes well for tourism on this island, a popular vacation destination on the Mediterranean. Security checkpoints sit at the entrances of Hara Kabira — the part of the island where most of Djerba's Jews reside — and plainclothes police patrol the neighborhood. Outside El Ghriba synogogue, police guard the entrance gate where visitors must pass through metal detectors and tight security checks.” ~

Anti-Semitism and Terrorism Attacks on Jews in Tunisia

In the 1980s, some Islamist openly preached anti-Semitism. Some Jews were harassed, Around that time many Jews left for Israel or France. The government cracked down on anti-Semitism after Ben Ali came to power. Bands of youth have attacked synagogues in Tunisia. But most Jews in Tunisia had long said they had never been the victims of attacks or anti-Semitism. In 1985, four Jews were killed when a security guard at Ghriba synagogue opened fire on worshipers. The killers had lost a relative who was killed in an Israeli air raid against Yasser Arafat, The Hamburg-based Tunisian Fighting Group is regarded as the most radical and militant of Tunisia’s Islamic groups.

On April 11, 2002, an explosion caused by suicide bomber in a truck near the old and famous Ghrba synagogue on the island of Jerba killed 22 people—14 German tourists, a Frenchman, six Tunisians and the suicide bomber. The synagogue is the oldest in Tunisia and Africa. The attack took place when the synagogue was empty. No Jews were killed.

The government initially claimed the blast was the result of an accident. It took back that assertion when Al-Qaida claimed responsibility for the attack a few weeks later. Al-Qaida rarely takes claim for an attack. It seemed to have done so in this case because the attack didn’t generate enough media attention.

On the morning of April 11 Nawat parked the truck on a narrow road near a group of tourists standing near the synagogue. When a policemen approached the truck it exploded. A woman who was in the synagogue told the Independent, “I heard this sound, a huge bang...Some of the windows blew in. I didn’t know what was going on...Then fire seemed to pour into the place.

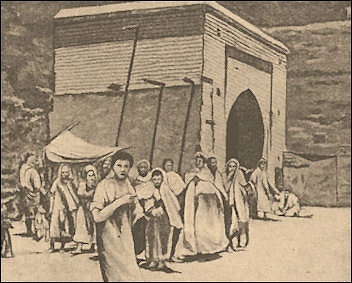

Jewish women in Tripoli

The suicide bomber that carried out the mission was Nizar Nawat, a 24year-old Tunisian high school drop out who had been trained at an Al-Qaida camp in Afghanistan. With $20,000 he received from Al-Qaida, he bought an old truck, got his uncle to install a large tank on it and filled that tank with propane. Nawat relatives said he showed little interest in Islam, drank alcohol and wore short pants. No one suspected he was a terrorist. He is believed to have turned to Islamic militancy after he worked nine months in South Korea but was cheated out of his wages by his employer and ended up in Montreal, where befriended some radical Algerians.

Libyan Jews

The last Jew in Libya, 80-year-old Rina Debach, left the country in 2003. But that doesn’t mean that Jews didn’t have a long history in Libya. According to Associated Press: “Jews first arrived in what is now Libya about 2,300 years ago. They settled mostly in coastal towns such as Tripoli and Benghazi and lived under a shifting string of rulers, including Romans, Ottoman Turks, Italians and ultimately the independent Arab state that was run by Gaddafi for nearly 42 years. Some prospered as merchants, physicians and jewellers. Under Muslim rule, they saw periods of relative tolerance and bursts of hostility. Italy took over in 1911, and eventually the fascist government of Benito Mussolini issued discriminatory laws against Jews, dismissing some from government jobs and ordering them to work on Saturdays, the Jewish day of rest. [Source: Associated Press, October 3, 2011 |||]

“In the 1940s, thousands were sent to concentration camps in North Africa where hundreds died. Some were deported to concentration camps in Germany and Austria. In the decades after the war, thousands of Jews left Libya, many of them for Israel. David Gerbi's family fled to Rome in 1967, when Arab anger was rising over the war in which Israel captured the West Bank, East Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip. Two years later, Gaddafi expelled the rest of Libya's Jewish community, which at its peak numbered about 37,000. Gerbi said his family went to Italy to escape tensions, thinking they would return someday, but those hopes were dashed by Gaddafi's expulsion order. Some relatives later went to Israel, but he chose to remain in Italy.

History of the Jews in Libya

Under the Ptolemies (305-30 B.C.), Cyrenaica (coastal Libya) had become the home of a large Jewish community, whose numbers were substantially increased by tens of thousands of Jews deported there after the failure of the rebellion against Roman rule in Palestine and the destruction of Jerusalem in A.D. 70. Some of the refugees made their way into the desert, where they became nomads and nurtured their fierce hatred of Rome. They converted to Judaism many of the Berbers with whom they mingled, and in some cases whole tribes were identified as Jewish. In 115 the Jews raised a major revolt in Cyrenaica that quickly spread through Egypt back to Palestine. The uprising was put down by 118, but only after Jewish insurgents had laid waste to Cyrenaica and sacked the city of Cyrene. Contemporary observers counted the loss of life during those years at more than 200,000, and at least a century was required to restore Cyrenaica to the order and prosperity that had meanwhile prevailed in Tripolitania. By the beginning of the second century, Christianity had been introduced among the Jewish community, and it soon gained converts in the towns and among slaves. *

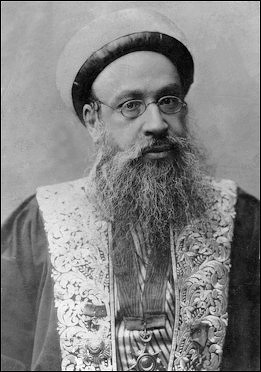

Libyan rabbi Eliyahu Chazan

After the Arab conquest, North Africa was governed by a succession of amirs (commanders) who were subordinate to the caliph in Damascus and, after 750, in Baghdad. In 800 the Abbasid caliph Harun ar Rashid appointed as amir Ibrahim ibn Aghlab, who established a hereditary dynasty at Kairouan that ruled Ifriqiya and Tripolitania as an autonomous state that was subject to the caliph's spiritual jurisdiction and that nominally recognized him as its political suzerain. The Aghlabid amirs repaired the neglected Roman irrigation system, rebuilding the region's prosperity and restoring the vitality of its cities and towns with the agricultural surplus that was produced. At the top of the political and social hierarchy were the bureaucracy, the military caste, and an Arab urban elite that included merchants, scholars, and government officials who had come to Kairouan, Tunis, and Tripoli from many parts of the Islamic world. Members of the large Jewish communities that also resided in those cities held office under the amirs and engaged in commerce and the crafts. Converts to Islam often retained the positions of authority held traditionally by their families or class in Roman Africa, but a dwindling, Latinspeaking , Christian community lingered on in the towns until the eleventh century. The Aghlabids contested control of the central Mediterranean with the Byzantine Empire and, after conquering Sicily, played an active role in the internal politics of Italy. Jews and moriscos, descendants of Muslims expelled from Spain in the sixteenth century, were active as merchants and craftsmen, some of the moriscos also achieving notoriety as pirates.

The June 1967 War between Israel and its Arab neighbors aroused a strong reaction in Libya, particularly in Tripoli and Benghazi, where dock and oil workers as well as students were involved in violent demonstrations. The United States and British embassies and oil company offices were damaged in rioting. Members of the small Jewish community were also attacked, prompting the emigration of almost all remaining Libyan Jews.

the Arab Socialist Union (ASU), was created in 1971 and modeled after Egypt's Arab Socialist Union. Its intent was to raise the political consciousness of Libyans and to aid the RCC in formulating public policy through debate in open forums. All other political parties were proscribed. Trade unions were incorporated into the ASU and strikes forbidden. The press, already subject to censorship, was officially conscripted in 1972 as an agent of the revolution. Italians and what remained of the Jewish community were expelled from the country and their property confiscated.*

Restoring Tripoli’s Last Synagogue

In 2011, David Gerbi, Libya's 'revolutionary Jew', received permission from new rulers of Libya to return to Libya to restore Tripoli last synagogue. Gerbi's family fled Tripoli in 1967. Gaddafi expelled the rest of Libya's 38,000 Jews two years later and confiscated their assets. Associated Press reported: “Gerbi, a 56-year old psychoanalyst returned to his homeland after 44 years in exile to help oust Muammar Gaddafi, and to take on what may be an even more challenging mission. That job began on Sunday, when he took a sledgehammer to a concrete wall. [Source: Associated Press, October 3, 2011 |||]

“Behind it, the door to Tripoli's crumbling main synagogue, unused since Gaddafi expelled Libya's small Jewish community early in his decades-long rule. Gerbi knocked down the wall, said a prayer and cried. "What Gaddafi tried to do is to eliminate the memory of us. He tried to eliminate the amazing language. He tried to eliminate the religion of the Jewish people," said Gerbi, whose family fled to Italy when he was 12. "I want bring our legacy back, I want to give a chance to the Jewish of Libya to come back."” |||

“The star of David is still visible inside and outside the peach-coloured Dar al-Bishi synagogue in Tripoli's walled Old City. An empty ark where Torah scrolls were once kept still reads Shema Israel (Hear, O Israel) in faded Hebrew. But graffiti is painted on the walls, and the floor and upper chambers are covered in garbage – plastic water bottles, clothes, mattresses, drug paraphernalia and dead pigeon carcasses. He and a team of helpers carted in brooms, rakes and buckets to prepare to clean it out. |||

“It took Gerbi weeks to get permission from Libya's new rulers to begin restoring the synagogue, which is part of his broader goal of promoting tolerance for Jews and other religions in a new Libya. "My hope and wish is to have an inclusive country," he said. "I want to make justice, not only for me, but for all the people of Libya for the damage that Gaddafi did." |||

“Gerbi returned to his homeland this summer to join the rebellion that ousted Gaddafi, helping with strategy and psychological issues. He rode into the capital with fighters from the western mountains as Tripoli fell in late August. Now he has hired neighbourhood residents to help clean and renovate the synagogue in Hara Kabira, a sandy slum that was once Tripoli's Jewish quarter. He said he was funding the synagogue renovation himself, and plans to stay until his project is complete. He called it a test of tolerance for Libya's new rulers. "I plan to restore the synagogue, I plan to get the passport back, I plan to resolve the problem of the confiscated property, individual and collective," he said. "I plan to help rebuild Libya, to do my part." Gerbi isn't sure how many Jewish properties were confiscated, but he hopes to find a way to resolve that issue and build a garden memorial on the site of the former Jewish cemetery, which Gaddafi had covered with high-rise buildings and a car park.

Libya's acting justice minister, Muhammad al-Alagi, said Gerbi could appeal for justice. "If he was discriminated at some time, Libyan courts are open for his claims," he told the Associated Press. Gerbi, who fearlessly wore a yarmulke on Sunday and likes to take walks on the seaside street outside the protective confines of his hotel to clear his head, considers himself a Jewish ambassador of goodwill.

He said he faced some hostility in the beginning but has been able to overcome it with old-fashioned glad-handing, although he acknowledges concerns are high about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the influence of the Muslim Brotherhood. Dar al-Bishi is one of the few Libyan synagogues with the potential to be restored. Others have been demolished or put to other uses. Some were turned into mosques.

This is not Gerbi's first trip back to Libya. He returned in 2002, when he agreed to help Gaddafi's efforts to normalise relations with the international community and helped an ailing aunt leave the country. Gerbi said she had been Libya's last remaining Jew. Gerbi saw the Tripoli synagogue during another trip five years later, and even met Gaddafi in Rome in 2009. But in the end, all his efforts were stonewalled. "I thought Gaddafi was really with great intentions, but it was all a lie," he said.

Gerbi is hopeful about Libya's future, although he has not yet been allowed to join the National Transitional Council, which is now governing Libya, as a full representative. Jalal el-Gallal, an NTC spokesman, said Gerbi's efforts to restore the synagogue were premature because the government is still temporary and revolutionary forces are fighting Gaddafi supporters on two major fronts. "I think it's just creating a lot more complications at the moment," he said. One endorsement Gerbi has received is from the synagogue neighbourhood's main sheik, who also offered him protection. "The NTC says, 'You have to wait. It's a sensitive subject,'" Gerbi said. "I don't want to wait. Why should I wait when I did the revolution?

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu Wikipedia, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024