Home | Category: Science and Mathematics

SCIENCE IN BABYLON AND MESOPOTAMIA

Nimrud lens Mesopotamia gave the world writing, the zodiac, the 12-month year, the 60-minute hour, the 360-degree circle, the potter's wheel, sailboats, wheeled vehicles, kiln-fired bricks, maps and irrigation. The Babylonians conducted censuses of agriculture. The Neo- Babylonian ruler Ashurbanipal founded the world’s first known serious library. Archaeologists found the library and unearthed good copies of the epic of Gilgamesh and Mesopotamia poetry there.

Mesopotamian cultures developed astronomy, mathematics, logarithms and exponents values. They were able to calculate compound interests but algebraic and geometrical problems could not be solved. In ancient times people, sciences such as chemistry, biology and physics did not exist. People believed that natural processes were caused by spirits. Even so, a great deal of practical knowledge was ascertained. The properties of metals were observed and processes such as glassmaking and alloy production were figured out.

Larry Freeman wrote in his Astronomy & Navigation Page:“The Babylonians were great astronomers, they noticed that they to adjust their observations every day also. Also their calendar had 12 months of 30 days and 5 year end holidays giving 365 days a year. It was hard to compute fractions of 365 (they did not have multiplication or division) so they used 360 as the number of days for astronomy. They divided a circle into 360 parts so by setting it back one part every day they could keep the observations of the stars constant from one day to the next (within 1.5 percent). The number 360 is 345*6 which give a great many factors and therefore great for doing ratios. This is where we got 360 degrees in a circle. Note: Modern day observers use {1/364.24219889 - .0000000614(t-1900) — sidereal time} to adjust their observations. The Babylonians were less than 1.5 percent off or about 5 degree per year. This was good since there were no accurate way to keep time in those days. The would occasionally adjust their based on the helical rising of certain stars. These are the stars that would just have risen in the area of the sun when the sun rises. [Source: Larry Freeman's Astronomy & Navigation Page]

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Lost Discoveries: The Ancient Roots of Modern Science – from the Babylonians to the Maya” by Dick Teresi (2010) Amazon.com;

“Before Nature: Cuneiform Knowledge and the History of Science” by Francesca Rochberg (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian World” by Gwendolyn Leick (2007) Amazon.com;

“Mathematics in Ancient Iraq: A Social History” by Eleanor Robson (2008) Amazon.com;

“Architecture and Linear Measurement during the Ubaid Period in Mesopotamia” (BAR International) by Sam Kubba (1998) Amazon.com;

"Ancient Inventions” by Peter James and Nick Thorpe (Ballantine Books, 1995) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Knowledge Networks: A Social Geography of Cuneiform Scholarship in First-Millennium Assyria and Babylonia” by Eleanor Robson (2019) Amazon.com;

“Scholars and Scholarship in Late Babylonian Uruk” by Proust, Christine Proust, et al. (2019) Amazon.com;

“Philosophy Before the Greeks: The Pursuit of Truth in Ancient Babylonia” by Marc Van De Mieroop (2015) Amazon.com;

Astrology in Ancient Mesopotamia: The Science of Omens and the Knowledge of the Heavens by Michael Baigent (2015) Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamian Astrology: An Introduction to Babylonian and Assyrian Celestial Divination” by Ulla Susanne Koch (1995) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian Astrolabe: The Calendar of Creation” (State Archives of Assyria Studies)

by Rumen Kolev (2013) Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamian Cosmic Geography” by Wayne Horowitz (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World” by David W. Anthony (2010) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamian Materials and Industries: The Archaeological Evidence”

by P. R. S. Moorey (1999) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian Astronomical Compendium” by Hermann Hunger (2020) Amazon.com;

“Culinary Technology of the Ancient Near East From the Neolithic to the Early Roman Period” by Jill L. Baker (2014) Amazon.com;

“Lithic Technology of Neolithic Syria” (BAR Archaeopress) by Yoshihiro Nishiaki (2000) Amazon.com;

“An Ancient Mesopotamian Herbal” by Barbara Boeck, Shahina A. Ghazanfar, et al. (2024) Amazon.com;

First Wheels and Wheeled Vehicles

The wheel, some scholars have theorized, was first used to make pottery and then was adapted for wagons and chariots. The potter’s wheel was invented in Mesopotamia in 4000 B.C. Some scholars have speculated that the wheel on carts were developed by placing a potters wheel on its side. Other say: first there were sleds, then rollers and finally wheels. Logs and other rollers were widely used in the ancient world to move heavy objects. It is believed that 6000-year-old megaliths that weighed many tons were moved by placing them on smooth logs and pulling them by teams of laborers.

The wheel, some scholars have theorized, was first used to make pottery and then was adapted for wagons and chariots. The potter’s wheel was invented in Mesopotamia in 4000 B.C. Some scholars have speculated that the wheel on carts were developed by placing a potters wheel on its side. Other say: first there were sleds, then rollers and finally wheels. Logs and other rollers were widely used in the ancient world to move heavy objects. It is believed that 6000-year-old megaliths that weighed many tons were moved by placing them on smooth logs and pulling them by teams of laborers.

Early wheeled vehicles were wagons and sleds with a wheel attached to each side. The wheel was most likely invented before around 3000 B.C.”the approximate age of the oldest wheel specimens — as most early wheels were probably shaped from wood, which rots, and there isn't any evidence of them today. The evidence we do have consists of impressions left behind in ancient tombs, images on pottery and ancient models of wheeled carts fashioned from pottery.◂

Evidence of wheeled vehicles appears from the mid 4th millennium B.C., near-simultaneously in Mesopotamia, the Northern Caucasus and Central Europe. The question of who invented the first wheeled vehicles is far from resolved. The earliest well-dated depiction of a wheeled vehicle — a wagon with four wheels and two axles — is on the Bronocice pot, clay pot dated to between 3500 and 3350 B.C. excavated in a Funnelbeaker culture settlement in southern Poland. Some sources say the oldest images of the wheel originate from the Mesopotamian city of Ur A bas-relief from the Sumerian city of Ur — dated to 2500 B.C. — shows four onagers (donkeylike animals) pulling a cart for a king. and were supposed to date sometime from 4000 BC. [Partly from Wikipedia]

In 2003 — at a site in the Ljubljana marshes, Slovenia, 20 kilometers southeast of Ljubljana — Slovenian scientists claimed they found the world’s oldest wheel and axle. Dated with radiocarbon method by experts in Vienna to be between 5,100 and 5,350 years old the found in the remains of a pile-dwelling settlement, the wheel has a radius of 70 centimeters and is five centimeters thick. It is made of ash and oak. Surprisingly technologically advanced, it was made of two ashen panels of the same tree. The axle, whose age could not be precisely established, is about as old as the wheel. It is 120 centimeters long and made of oak. [Source: Slovenia News]

Ur chariot The wheel and axle were found near a wooden canoe. Both the wheel and the axle had been scorched, probably to protect them against pests. Slovenian experts surmise that the wheel they found belonged to a single-axle cart. The aperture for the axle on the wheel is square, which means the wheel and the axle rotated together and, considering the rough ground, the cart probably had only one axle. We can only guess what the cart itself was like. The Ljubljana marshes are a perfect place for old objects to be preserved. There have been many finds uncovered in this area. Apart from the wooden wheel, axle and canoe, there have been innumerable objects found which are up to 6,500 years old.

A wheel dated to 3000 B.C., was found near Lake Van in eastern Turkey. Wheels with similar dates have been found in Germany and Switzerland. One very old wheel was a wooden disc discovered at an archeological sight near Zurich. The wheel now can be seen in the Zurich museum.

The invention of the wheel paved the way for more advanced technology such as pulleys, gears, cogs and screws. A flint point or stick spun with a bow was another important advancement. It could be used to make fire and employed as a drill.

See Separate Article ANCIENT HORSEMEN AND THE FIRST WHEELS, CHARIOTS AND MOUNTED RIDERS factsanddetails.com

Calendars and Time Measurements in Mesopotamia

What may be the world’s oldest calendar was unearthed in Iraq. It is 10,000 years old and is comprised of a pebble with 12 notches. There were various Sumerian calendars. Ones with 12 months of 30 days, which added up to 360 day years, soon fell out of sync with the season so extra months were added every few years. The Eblaite calendar affixed a different name to every year that commemorated a great event. The year 2480 B.C., for example, is referred to as “ Dis mu til Mari ki” (the Year of the defeat of Mari).

The Babylonians are often given credit for devising the first calendars, and with them the first conception of time as an entity. They developed and used the 360-day year — divided into 12 lunar months of 30 days (real lunar months are 29½ days) — devised by the Sumerians and introduced the seven day week, corresponding to the four waning and waxing periods of the lunar cycle. The ancients Egyptians adopted the 12-month system to their calendar. The ancient Hindus, Chinese, and Egyptians, all used 365-day calendars.

The Mesopotamians also invented the 60 minute hour. The idea of measuring the year was more important than measuring the day. People could judge the time of day by following the sun. Judging the time of year was more difficult and important in knowing when to plant crops, expect rain or snow and harvest crops. That is why a yearly calendar was developed before clocks and minutes and seconds didn’t come to the Middle Ages.

See Separate Article: CALENDARS, TIME MEASUREMENTS AND SEASONS IN MESOPOTAMIA africame.factsanddetails.com

Sumerian Calendar

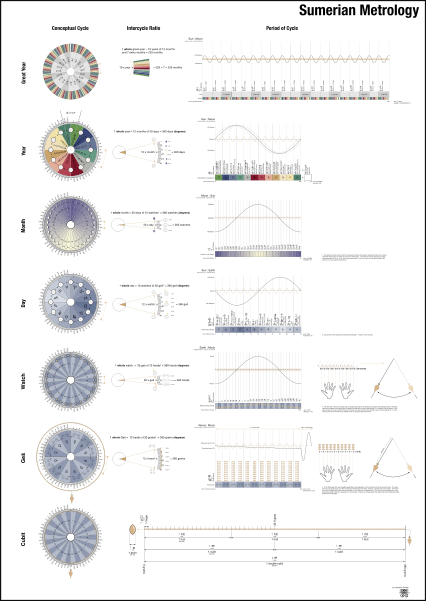

Mesopotamian Measurement

The Sumerians had standard measurements of length, area and volume. The mina was the standard weight measurement. It was divided into 60 shekels, which roughly equivalent to a pound. Sixty minas made up one talent.

Stone blocks from the Sumerian period, dated to 2400 B.C., have been found that have the roughly equivalent weight of around 24 ounces and are inscribed with the same name. They may be part of a system of weights and measurements.

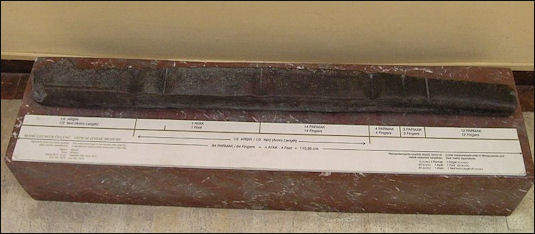

The world's oldest known long-distance linear measurement is the "farsang” — a measurement of about four miles used in Babylon 4,000 years ago. A cubit, based on the length of a man's forearm, was the unit of measure throughout much of the ancient world. The measurement varied a great deal however. In ancient Egypt, for example, a cubit for a man was 17.72 inches while the cubit for a king was 20.62 inches.

Nippur cubit

Astronomy in Ancient Mesopotamia

The Mesopotamians invented astronomy. A Sumerian cuneiform tablet in the British Museum describes the sighting on an exploding star in 4000 B.C. Modern astronomers have found the remnant of a star that may have exploded at that time.

The Babylonians excelled at astronomy. Many of the constellations that we see in the sky were first categorized by them. The kept careful records and recorded celestial events under the belief they could shape future events. Under Hammurabi the Lawgiver, in 1800 B.C., star catalogs and planetary records were compiled.

The Neo-Babylonian used ziggurats as observatory and mapped the night time sky into constellations. They developed the 12 signs of the zodiac, recorded the motions of the planets and even predicted eclipses.

Babylonian astronomers, writing on cuneiform tablets, used surprisingly sophisticated geometry to calculate the orbit of what they called the White Star — the planet Jupiter — according to Mathieu Ossendrijver of Humboldt University in a paper published in the journal Science. By comparing a tablet named BM 40054 by the British Museum, and dubbed Text A by Ossendrijver, to the four previously mysterious tablets, Ossendrijver was able to decipher that the five tablets computed the predictable motion of Jupiter relative to the other planets and the distant stars. “This tablet contains numbers and computations, additions, divisions, multiplications. It doesn’t actually mention Jupiter. It’s a highly abbreviated version of a more complete computation that I already knew from five, six, seven other tablets," he said. [Source: Joel Achenbach, Washington Post, January 28, 2016 |||]

Joel Achenbach wrote in the Washington Post: “Most strikingly, the methodology for those computations used techniques that resembled the astronomical geometry developed in the 14th century at Oxford's Merton College. The tablets have been authoritatively dated to a period from 350 B.C. to 50 B.C. "This discovery shows that there is still more to learn about ancient science, and that every new thing we do learn demonstrates just how clever the ancient astronomers were," said John Steele, a Brown University professor who specializes in ancient astronomy and was not involved in the new study.|||

See Separate Article: BABYLONIAN AND MESOPOTAMIAN ASTRONOMY africame.factsanddetails.com

Maps in Ancient Mesopotamia

The world's oldest map is a clay tablet with the Euphrates River and Mesopotamia. It dates back to 2250 B.C. A Babylonian world map was drawn on clay in 900 B.C. A world map, dated at 600 B.C., show Babylon as a rectangle pierced by two vertical lines representing the Euphrates River. Small circles indicates other kingdoms. An ocean surrounds the world.

Daniel Weiss wrote in Archaeology magazine: Cuneiform tablets were long used for making maps and plans of towns, rural areas, and houses, but rarely for anything larger or without commercial interest. A unique tablet, thought to have come from Sippar in present-day Iraq and dating to around the sixth century B.C., shows much more and reflects something of how ancient Babylonians saw themselves in the world. This Mesopotamian mappa mundi consists of a circular map surrounded by triangles, with explanatory text above and on the opposite face. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2016]

The central circle shows the Babylonian realm, bisected by the Euphrates, which is straddled by Babylon itself. Several other geographical areas are labeled by name, and the continent is surrounded by a ring called the “ocean” or “Bitter River.” Beyond the boundary waters are seven or eight outlying regions or islands represented by triangles, of which portions of four survive. The text is largely concerned with these far-flung, perhaps mythological, places. One is described as a “place where the sun is not seen,” another as a place where “a winged bird cannot safely complete its journey.” Further descriptions speak of “ruined” cities and gods, and animals both fantastic (great sea-serpent, scorpion-man) and exotic (lion, monkey, chameleon). According to Wayne Horowitz of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the tablet “reflects a general interest with distant areas during the first half of the first millennium, when the Assyrian and Babylonian Empires reached their greatest extents.”

Gold, Bronze, Iron and Mesopotamia Metallurgy

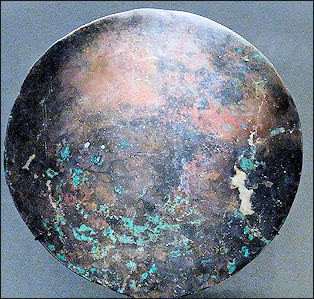

Mari Pyxid Bronze was first developed in Iran, various places in the Middle East and Southeast Asia, but Mesopotamian cultures invented many of the metalworking processing we still rely on today: smelting from ore, casting, alloying and soldering.

Iron made possible sturdy plows and strong weapons. Crude iron was first used around 2000 B.C. Improved iron working from the Hittites became wide spread by 1200 B.C.

Mesopotamia didn't have its own source of metal ores. It imported them from other places. Ores and precious metals were obtained through long distance caravan trade with places like southern Anatolia and present-day Jordan.

The ancients determined the quality of gold by making a streak on it with a hard, black stone known as a touchstone, The brightness of the streak was an indication of the amount of gold. As early as 1500 B.C. the Mesopotamians learned how to purify gold by "cuppelation," in which impure gold was heated in a porcelain cup. The impurities were absorbed into the porcelain and pure gold remained.

One of the most effective weapons that was developed was the double headed ax head which could mounted socket-fashion onto a handle.

See Separate Article: MINING, BRONZE, GOLD AND TIN IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA africame.factsanddetails.com

Ancient Inventions

The book “Ancient Inventions”by Peter James and Nick Thorpe (Ballantine Books, 1995) is a compendium of curiosities dating from the Stone Age to 1,000 A.D., the book argues that just because our ancestors lived long ago and had less technology at their disposal does not mean they were any less intelligent than we are. [Source: Laura Colby, New York Times, May 16, 1995]

Mari mirror “In fact, many of the inventions that we believe belong to our own modern era already existed hundreds, sometimes even thousands of years ago. Our ancestors were not quaint superstitious people mystified by the problems of everyday life; they were, much as we are today, hard at work on ingenious solutions. The authors have broken down the inventions into different categories such as medicine; food, drink and drugs; transportation and communications; and military technology, making the book easy to thumb through in the coffee-table style, rather than one to be read from start to finish.

“We learn that our ancestors used birth control — everything from a condom to a rudimentary form of the pill — abused drugs ranging from hallucinogenic mushrooms to cocaine, and were entertained by sport, music and theater. We see homes many thousands of years old with plumbing, indoor ovens, and many other conveniences we associate with our own era.

“But by far the most interesting parts of the book are those that provide examples of technology, rather than everyday objects. Inhabitants of present-day Iraq, for instance, had developed a form of electric battery about 2,000 years ago, using a clay jar that contained a copper rod sealed with asphalt. The so-called Baghdad Battery, discovered in 1936, was probably used by jewelers to electroplate bronze jewelry. Medicine, including brain surgery, the making of artificial limbs and plastic surgery, is one of the most hair-raising chapters. Early military technology, including a "machine gun" in the form of a crossbow that could fire 20 arrows in less than 15 seconds, is also covered.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2024