Home | Category: Jews in the Greco-Roman Era

HEROD

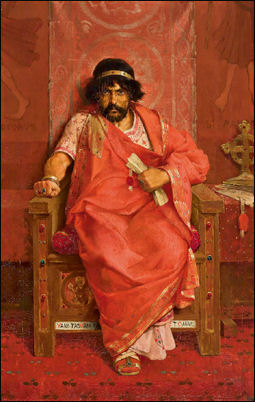

Herod by Lybaert Herod the Great was a Jewish leader installed by the Romans after they took full control Palestine. Regarded as puppet king of the Roman Senate, he took power in 37 B.C. and ruled until around 4 B.C. and served under Julius Caesar, Mark Antony and the Emperor Augustus. He is remembered most for building the Great Temple for the Jews in Jerusalem and ordering the death of male children in Bethlehem after Jesus was born. His son Herod Antipas was involved in Jesus's trial. He was the ruler of Judea at time of the death of John the Baptist and Jesus.

David L. Silverman of Reed College wrote: “Herod is a difficult figure to assess. The length of his rule and vastness of his legacy, especially as it can be gauged from his extensive building projects both at home and abroad (e.g. at Athens and Rhodes), conspire to make him a very controversial figure. His detractors insisted that he was a monster for murdering many members of his family who were or could produce rivals. In this, of course, Herod merely behaved like the standard Hellenistic monarch. But we need to ask whether Herod's Judea contained the roots of the rebellion which led to the disaster of 70 AD, and for that it is necessary to consider how he shaped the society of Judea. [Source: David L. Silverman, 1996, Internet Archive, Reed College]

Eric Meyers at Duke University told PBS: “There's nobody in all Jewish history, I could say without hesitation, who has had a greater influence on the material culture and splendor of Palestine Israel than Herod the Great. His building plan was ambitious beyond expectation, beyond belief. And his ability to bring local resources as well as foreign resources to bear on his public works program was unparalleled. And this was especially interesting because he was such a nasty person, such a evil man in many ways, but he was a brilliant strategist, and a brilliant politician. And his public works program, coming as it did after the great earthquake of 31 B.C., was a way of bringing diverse communities together in Palestine. He brought Pharisees together with the Essenes and all sorts of people. His public works really brought the community back together. And it is one of the real untold ironies of Jewish history that this man, who's the guy you love to hate in Jewish history really, leaves the most indelible mark on the face of the land of Israel. Whether it's the western wall or the Temple itself, with all of its splendor, or the great amphitheater at Caesarea, or the harbor at Caesarea, all of these magnificent monuments are attributed to him and his working relationship with both local indigenous peoples as well as foreign sponsors. [Source: Frontline, PBS, “Eric Meyers, Professor of Religion and Archaeology Duke University, April 1998]

L. Michael White of the University of Texas told PBS: “Herod the Great was probably one of the greatest kings of the post-Biblical period in Israel, but you wouldn't want your daughter to date him. He was ambitious, brutal, extremely successful; he brooked no opposition, either with family or with politics. He was ... a genius of [a] self-made man. Thanks to the political connections of his father, he was able to marry into the ruling family in Judea. And it was under his kingship that post-Biblical Israel really rose to its political and material heights in the early days of the Roman Empire. Herod was a successful client king, which meant that as long as he paid tribute to Rome and was on the correct side of any kind of Roman fracas, he protected the political independence and liberty of Jews in Israel. And... he did that very well. He also advertised the success and wealth of his own regime and the importance of his people by having an incredibly ambitious program of building ... some of the most beautiful buildings that we have still existing in the land of Israel were done under Herod. Of course, his great architectural gift to posterity was what he did with the Temple in Jerusalem. [Source: L. Michael White, Professor of Classics and Director of the Religious Studies Program University of Texas at Austin, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

RELATED ARTICLES:

JEWS IN THE EARLY ROMAN ERA africame.factsanddetails.com ;

ANCIENT JEWISH SECTS: PHARISEES, SADDUCEES, ESSENES AND ZEALOTS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SECOND TEMPLE OF JERUSALEM (HEROD'S TEMPLE) africame.factsanddetails.com ;

LIFE OF THE JEWS AROUND THE TIME OF JESUS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

UNREST AND PERSECUTION OF JEWS IN THE A.D. FIRST CENTURY ROMAN EMPIRE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

JEWISH WARS AND REVOLTS AGAINST ROME africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MASADA: HISTORY, ARCHAEOLOGY, MASS SUICIDE africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SIEGE OF JERUSALEM BY THE ROMANS IN A.D. 70 africame.factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY JEWISH DIASPORA: 600 B.C. TO A.D 500 africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Virtual Jewish Library jewishvirtuallibrary.org/index ; Judaism101 jewfaq.org ; torah.org torah.org ; Chabad,org chabad.org/library/bible ; Bible and Biblical History: ; Biblical Archaeology Society biblicalarchaeology.org ; Bible History Online bible-history.com Bible Gateway and the New International Version (NIV) of The Bible biblegateway.com ; King James Version of the Bible gutenberg.org/ebooks ; Jewish History: Complete Works of Josephus at Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL) ccel.org ; Jewish History Timeline jewishhistory.org.il/history Jewish History Resource Center dinur.org ; Center for Jewish History cjh.org ; Jewish History.org jewishhistory.org ; Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Christianity: BBC on Christianity bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity ; Christian Classics Ethereal Library www.ccel.org ; Sacred Texts website sacred-texts.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Herods: Murder, Politics, and the Art of Succession”

by Bruce Chilton, Paul Heitsch, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Herod's Temple: A Useful Guide To The Structure And Ruins Of The Second Temple In Jerusalem” by Michael Lustig Amazon.com ;

“An Introduction to Second Temple Judaism: History and Religion of the Jews in the Time of Nehemiah, the Maccabees, Hillel, and Jesus” by Lester L. Grabbe Amazon.com ;

“Jews In The Roman World” by Michael Grant Amazon.com ;

“The Jews among the Greeks and Romans: A Diasporan Sourcebook”

by Professor Margaret Williams Amazon.com ;

“Judea under Greek and Roman Rule” by David A. deSilva (2024) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Israel and Ancient Greece” by John Pairman Brown (2003) Amazon.com;

“A History of the Jewish People During the Babylonian, Persian, and Greek Periods”by Charles Foster Kent Amazon.com ;

“Hasmonean Realities behind Ezra, Nehemiah, and Chronicles” by Israel Finkelstein Amazon.com ;

“The Story of the Jews” Volume One: Finding the Words 1000 BC-1492 AD by Simon Schama (Author) Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jews” by Paul Johnson, Amazon.com Amazon.com

Herod Comes to Power

In 37 B.C., the Romans appointed Herod — an official in the Hasmonean administration — and a descendent of converts to Judaism, king of Judea. The Jewish Hasmonean Kingdom ruled Israel from 140 to 63 B.C. when the Romans invaded and claimed Palestine. With the help of a Roman army, Herod defeated Antigonus, a grandson of Alexandra who had led a successful revolt against the Romans and reclaimed the Hasmonean throne. [Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s Encyclopedia.com]

Hershel Shanks wrote for PBS: “In the mid-sixties B.C., two royal Hasmonean sons engaged in a fratricidal war for the throne. One of these sons sought Roman help, and in 63 B.C. the Roman general Pompey conquered Jerusalem, effectively ending Jewish sovereignty, although Hasmonean rulers continued at least nominally to sit on the throne of a truncated kingdom for another quarter century.

“Then, in 40 B.C., Parthians from the east invaded Judea, wresting it from the Romans and appointing the last Hasmonean ruler (Mattathias Antigonus). At the time of the Parthian invasion, Herod, a Jew of Idumean and Nabatean lineage, subsequently known as Herod the Great, was serving as a Roman procurator. He promptly went to Rome to convince the Roman senate that only he could restore Roman rule. In 37 B.C. Herod led an army against the Parthians and after a bitter fight reconquered Jerusalem. [Source: Hershel Shanks, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

Herod Period in Palestinian and Biblical History

actor playing Herod in the Oberammergau passion play

Hershel Shanks wrote for PBS: “For thirty-three years Herod ruled Judea, as a Roman vassal. That he was hated by his Jewish subjects is well known. The Jewish historian Josephus tells of Herod's plan to have the leading men of Judea murdered at the time of his own death because he feared that otherwise his funeral might be an occasion for general rejoicing. Without question, Herod exercised his power through terror and brutality, but a further reason for his unpopularity was his violation of traditional Jewish law. He built numerous pagan temples and even staged gladiatorial contests in Jerusalem. However, he also rebuilt the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem on so grand a scale that it far eclipsed the original building constructed a millennium earlier by King Solomon. [Source: Hershel Shanks, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

“After Herod's death, in 4 B.C., social unrest became more open. Although Jewish client-kings of the Herodian dynasty pretended to govern a truncated Judea, brigands often ruled the countryside, and the Romans assumed more and more direct power. Riots were not uncommon, leading eventually to the outbreak of the First Jewish Revolt against Rome, which began in 66 A.D. and effectively ended in 70 A.D., when the Romans burned Jerusalem and destroyed the Temple.

“Judaism during this period has been described as "remarkably variegated." Some scholars have gone so far as to talk about Judaisms, rather than one Judaism. In those insecure times the traditional Judaism, centered in Temple sacrifice, was widely considered by Jews themselves inadequate to the stormy present. So, along with institutions like the synagogue, which would replace the Temple and become the focus of Jewish life thereafter, we also see the development of expectations of the end of time, of heavenly visions, of life after death, of resurrection of the dead, of apocalypses (revelations) where good and evil were to face each other in a final cosmic battle, and of messianic deliverers.”

Herod’s Life and Death

Herod by Tissot

Herod was born around 73 B.C. He was a descendant of Semitic princes and Jewish converts from Edom, a land south of Judea, that ruled from 47 B.C. to A.D. 93. His mother was an Arab princess. His father Idumean Antipater was appointed governor of Judea, Samaria and Galilee detractors insisted that by Julius Caesar around 47 B.C. Herod married ten times and sired many sons, many of whom were killed. He had a consuming passion for his stepdaughter Salome. He enjoyed drinking.

David L. Silverman of Reed College wrote: “Herod, who had inherited the title of procurator of Judea from his father Antipater, went to Rome after the Parthian invasion and persuaded the Senate to back his attempt to wrest Judea from Parthian control. Herod, together with Mark Antony's lieutenants Ventidius and Sosius, took Jerusalem in 37 and ruled 37-4 BC. A masterly politician, ruthless when he had to be, Herod was a fit counterpart for his contemporary Augustus. Like most of the client kings in the East, he supported Mark Antony over Octavian; yet after Actium he managed to persuade Augustus, with promises of loyalty proved good in the event, to leave him in place. [Source: David L. Silverman, 1996, Internet Archive, Reed College /+/]

Herod died at around the age of 69 of unusual diseases, perhaps Fournier's gangrene, whose symptoms include intense itching, convulsions on every limb and gangrene of the genitalia. Before he died Herod that all of Judea's nobles imprisoned and ordered that they all be killed on the day of his death so that all of Judea would be plunged into morning. When Herod finally did die, the nobles were released and everyone celebrated. After Herod's death his kingdom was divided up among three sons, who ended up fighting among themselves and destabilizing the region.

Herod as the Ruler of Judea

Herod loyally served his Roman overlords but also made concessions to the Jews. On one hand, he ruthlessly suppressed all opposition and reduced the power of the high priests and the Sanhedrin — supreme religious body of ancient Judaism,. But on the other hand, he allowed the Pharisees to continue to teach and interpret the Torah. Ruling during a period of prosperity, Herod engaged in an ambitious building campaign that included an extensive renovation of the Temple. There were also a number of instances in which he intercede on behalf of Jewish communities in quarrels with Roman authorities. [Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s Encyclopedia.com]

Herod was governor of Galilee when the Parthian Empire conquered Judea (then part of Rome) in 40 B.C. Herod made a shrewd move of abandoned Jerusalem, which he did in cover of night with 5,000 people , including his family, and voiced his support for Rome. After seeking refuge in Petra in present-day Jordan, the home of the Nabateans, his mother's people, he made his way to Rome, from which he returned, backed by a large army and conquered Jerusalem and became the king of Judea.

Herod held on to power by being ruthless to his enemies and using skillful diplomacy to handle volatile religious and regional difference. By observing Jewish customs and laws in public, but ignoring them in private, he was able to balance pleasing his overlords in Rome with placating the Jews he ruled over and who never accepted him as their leader. The “Great” title is said to have been given to Herod less out of admiration than out of irony for his arrogance and the fact he scorned the religious laws of his own people.

David L. Silverman of Reed College wrote: ““Herod was not insensitive to the "hot buttons" of his people. Josephus' Bellum Iudaicum is mostly favorable to Herod, depicting him as an essentially well-meaning ruler whose life was plagued by many disasters, and whose position forced him into certain acts of cruelty. But the Antiquitates Iudaicae reflects a tradition much less favorable to the king, making him out to be a tyrant who ruled through intimidation, encouraged the citizens to report on the slightest hint of dissent or dissatisfaction, and haled suspects away to his secret fortress at Hyrcania, after which they were never seen again. All the more reason, then, to believe what Josephus has to say in the AJ about Herod's attempts to avoid giving offense to traditional piety.”[Source: David L. Silverman, 1996, Internet Archive, Reed College /+/]

Herod's banquet

“Rebuilding the Temple at Jerusalem was only the most obvious example. Although Herod did finance and attach his name to the construction of pagan buildings, he was careful to keep these in non-Jewish areas. His splendid new port at Casearea stimulated trade through the kingdom. Coins which he minted for use in Judea bore no images. Intermarriage of foreign potentates with Jewish women, for political purposes, was not completely spurned; but Herod wisely insisted that the prospective groom had to be circumcised first. On the other hand, it was said that Herod had backed the building of a Roman amphitheater for gladiatorial contests at Jerusalem (though this is not confirmed by archaeological evidence) and, worst of all from the point of view of offending sensibilities, to have erected golden eagles, symbols of Roman overlordship, over the entrance to his rebuilt temple. /+/

“But most importantly, Herod protected the claim of the Jews to be free from participation in the worship of the Imperial cult, although he encouraged it for the Samaritans and Gentiles resident in Judea. At the state level, Herod skirted the problem by offering sacrifices to God, the God of the Jews, on behalf of Augustus rather than to him and Rome. Augustus rewarded Herod with the grant of special privileges for the Jews (SB I 206): “Whereas the Jewish people have been found well-disposed to the Roman people ... the Jews are to enjoy their own customs in accordance with their ancestral law .... and their sacred monies are to be inviolate and transmitted to Jerusalem, and they do not have to post bond for appearance in court on the Sabbath or on the day of preparation for it from the ninth hour.” /+/

Herod's Ruthlessness

Herod is said to have killed thousands of people in Jerusalem while he took power, and killed thousands after he took power, including family members, servants and bodyguards. He ordered the drowning of his brother-in law, Aristobulus, in one of the pools at his winter palace, and had the love of his life, his second wife Mariamme, killed, believing she had committed adultery.

Herod's Wife The Roman Emperor Augustus reportedly said. “I’d rather be Herod's pig than his son," in reference to fact that Herod murdered three of his sons for plotting against him and for a while followed the Jewish custom of not eating pork. Herod killed two his sons after his oldest son, and heir apparent, Antipater, convinced Herod the other sons were plotting against him. When he learned that Antipater planned to poison him Herod rose from his bed just five days he died to order Antipater's death.

Herod is most well known for ordering the slaughter of every male child under two in his attempt kill the "King of the Jews." It is unlikely that this happened for, according to some estimates, Christ was born four years after Herod died.

David L. Silverman of Reed College wrote: “Whereas the Hasmoneans had tried to expel pagans from Judea and thereby incurred a great deal of antipathy for their people from Greek authors, Herod reached back to the Philhellenic tradition of the third and early second centuries. To the Jews he was a Jew, or tried to be; he reinforced a separation between religious and political power by promoting new candidates to the high priesthoods, men from families with no priestly tradition, but who themselves had earned the appointment by their piety and knowledge of religious lore. His enemies impugned Herod's parentage, and claimed that he was only half-Jewish, on his father's side, and hence not truly a Jew at all. This is of little importance, because insults about parentage are a commonplace in the Hellenic tradition, now a constituent part of the collective unconscious in the East. More telling is to examine Herod's actions. He won and kept the favor of the Romans and leading Greek cities; did he do so by betraying his own people? The right answer is important, since Herod's legacy was determinative of relations between Rome and the Jews for many years after his death.” [Source: David L. Silverman, 1996, Internet Archive, Reed College /+/]

Herod the Builder

After coming to power Herod the Great launched an extensive building campaign that involved constructing fortresses, palaces, and even entire cities. Herod is known for building the great Temple of Jerusalem, the winter palace of Jericho and the fortress of Masada and founding the Mediterranean port of Caesarea Maritima. The palace garden at Jericho was elevated so that people strolling along the colonnades would see the flowers and foliage at sea level. The Roman chronicler Josephus wrote Herod had a "genius for grand designs" and that "through lavish expenditure" Herod "conquered nature itself.”

Caesarea Maritima L. Michael White of the University of Texas told PBS: “Herod's building programs, both in Caesarea, and throughout the countryside are very extensive. And this is seen, especially in the city of Jerusalem itself. It appears that Herod thought of Jerusalem as his showpiece. He really wanted to make it a place where people would come, just as people would have gone to Athens or Rome, or the great cities of the Mediterranean world. And so, when Herod built the city, or helped to rebuild the city, he did so on a monumental scale. And this can be seen in the rebuilding of the Temple. [Source: L. Michael White, Professor of Classics and Director of the Religious Studies Program University of Texas at Austin, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

In 2021, archaeologist announced the discovery a Herod-era Roman basilica complex in Ashkelon, on Israel’s Mediterranean coast. According to Archaeology magazine: The structure, which measures roughly 360 feet long and 130 feet wide, was a multipurpose public building where Ashkelon’s residents would have socialized, conducted business transactions, and even attended theater performances. It includes a colonnade with marble columns standing some 40 feet tall as well as a central hall and two side halls. The floors and walls of the building were also made of marble, which is thought to have been imported from what is now Turkey. The team, led by Israel Antiquities Authority archaeologists Rachel Bar-Natan, Sa’ar Ganor, and Federico Kobrin, uncovered coins near the building’s foundations that date to the reign of Herod. Some historical sources suggest that Herod’s family came from Ashkelon, explains Bar-Natan, suggesting the basilica may have been constructed during the rule of a king who had personal connections to the city. [Source: Marley Brown, Archaeology Magazine, September/October 2021]

Caesarea Maritima

Caesarea Maritima was Herod the Great's City on the Sea. It was the first city to have an entirely man-made harbor in the open sea away from a protective bay or peninsula. Using innovative engineering techniques, Herod created a harbor where no harbor had stood before from cement that hardened under water and was placed in wood forms set in place by divers. Huge sluices were installed to prevent silting.

Herod built the great city on the sea as a kind of grand finale after completing the Great Temple of Jerusalem, the winter palace of Jericho and the fortress of Masada. Around the harbor were placed temples and grand building that were occupied by Byzantines, Arabs and Crusaders, and endured until the 13th century when they were leveled by Mamluk Egyptians. Today, the ruins from the ancient city stretch along a three-kilometer (two-mile) section of the Mediterranean coast. They include an aqueduct that runs parallel with the shore on a white sandy beach, and a sanctuary devoted to the god Mithas.

The special cement used for the harbor was made from volcanic ash, and rock. It was first used to make 200-foot-wide breakwaters and later to make quays that supported warehouses and docks for 100 boats along with a light tower and a platform with statues. In the city surrounding the harbor was a large amphitheater, a hippodrome, luxurious villas, government buildings and a Roman temple dedicated to Augustus. An aqueduct from Mount Carmel, which required tunneling through six kilometers (four miles) of solid rock, supplied water for the baths and fountains.

Herodium

Herodium (11 kilometers form Jerusalem and 7 kilometers from Bethlehem) is a fortified summer palace and district capital built by Herod. Built into a cone-shaped man-made hill near the birthplace of the Biblical prophet Amos, it embraced ritual baths (with the remains of ancient wall mosaics), cisterns, upper and lower palace annexes, towers, gardens, burial ground, a synagogue and hidden apertures for sneak attacks. During a Jewish revolt in A.D. 66-70, rebels that took over palace chose mass surrender instead of surrendering to the Roman legions, like their comrades at Masada.

Caesarea Herod's Palace was a great circular bastion surrounded by double-concentric walls that reached a height of 70 feet walls and 100-foot towers at the for cardinal points. Besides costly living quarters the upper palace had a triclinium (Greco-Roman formal dining hall side dn three sides by a couch), and bathhouse with a domed hewn-stone ceiling with a oculus (round opening). At the base of the hill was a royal complex, known as Lower Herodium, that sprawled across 40 acres. It most recognizable structure was an enormous 70-x-30-meter pool, which contained a central island.

Herodium was built at great expense. A five-kilometer-long aqueduct was built to supply it with water. Ehud Netzer, a Hebrew University archaeologist who has worked at Herodium for more than 35 years, told Smithsonian magazine, “Herodium was built to solve the problem [Herod] himself created by making a commitment to be buried in the desert. The solution was to build a large palace, a country club — a place of enjoyment and pleasure.” An impressive 450-seat royal theater was built, Netzer believes, to host a visit by Marcus, Agrippa, Rome’s second in command, in 15 B.C.

In 2015, archaeologists from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem working at Herodium found evidence that Herod sometimes sacrificed extensive work on one grand construction plan in favor of another. Archaeology magazine reported: Researchers discovered a large corridor in the upper palace at Herodium, apparently designed to allow the king and his entourage direct access to the palace courtyard. The corridor was at least 65 feet high and supported by a network of arches, but was left unfinished and partially filled in with rubble when the king decided to turn the hilltop into a giant cone-shaped monument. “This was a huge project being done just for the sake of preserving his name,” says archaeologist Yakov Kalman. “This was probably done in the last 10 years of his life when Herod was not mentally stable.” [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2015]

Herod also installed massive bathtubs that weighed 1,500 kilograms (3,300) each in at least two of his residences — the Kypros Fortress and the Herodium — presumably to encourage Roman-style bathing culture. Archaeology magazine reported: “Both tubs were made of translucent calcite alabaster and were assumed to have been imported from Egypt as no quarries producing the fine stone were known to have existed in the Levant. But in 2022, archaeologist found that such alabaster could have been quarried from Te’omim Cave, on the western slopes of the Jerusalem hills. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology Magazine, September/October 2022]

Herod’s Tomb

In May 2007,Hebrew University archaeologist Ehud Netzer announced that he had found the tomb of King Herod in Herodium. Although no bones were found in sarcophagus and there were no identifying inscriptions Netzer determined it belonging to Herod based on the sarcophagus location and size (about 2½ meters long), the tomb size (10-x-10x-10- meters) , the quality the workmanship (the stones fit tightly together without mortar), the presence of smashed remains of engraved stones and its ornate appearance. Decorations included rosettes and distinctive lines. [Source: Barbara Kreiger, Smithsonian magazine, August 2009]

The tomb was found about halfway up the hill on which Herodium was built. Three digs revealed separate sections of a stone platforms, upon which the king’s body was supposedly laid. Netzer said he believed the platform supported a flight of stairs that led to Herod’s living quarters and pool. Such a building would have befitted a king he said. Netzer added the finds were consistent the description of Herod’s funeral by the 1st century historian Josephus Flavius. Situated near Herod’s tomb are other tombs thought to have belonged to some of Herod’s wives.

Herod's tomb? Describing Herod’s funeral several years after it happened Josephus Flavius wrote: “The bier was of solid gold, studded with precious stones and had a covering of purple, embroidered with various colors; on this lay the body enveloped in purple robe, a diadem encircling the head and surmounted by a crown of gold , the scepter beside the right hand.”

People that have included a French explorer, Italian Biblical scholar and a Silicon Valley geophysicist, had been searching for the tomb for more than 100 years. Netzer spent 35 years looking for it. He also worked on the excavations at Masada with famed archaeologist Yiguel Yadin and is credited with finding the pool where Herod’s brother-in law, Aristobulus was drowned.

There were some doubts as to whether the tomb really belongs to Herod. Shimon Gibson of the Albright Archaeological Institute in Jerusalem told the Times of London, the science is “quite compelling. This is a very promising discovery but we need evidence that this was the final resting place and not just another chamber.” Wael Hamamredm director of the Palestinian Antiquities Authority said, “If this is indeed the burial site of a king, where is the inscription? Where are bones? Why would they choose to bury him here?” Netzer said the absence of bones and the broken bones suggest the grave was probably looted and destroyed during the Jewish revolt against the Romans in A.D. 66 and A.D. 72.

Eric Meyers,a professor at Duke, told the Los Angeles Times, “Because of the context, it sound like a royal tomb...I’m one of the most suspicious guys there is, but finding a tomb halfway up the side of Herodium is a pretty good indication that this is it.” Jodi Magness, an archaeologist at the University of North Carolina, told Smithsonian magazine, “In terms of size, quality of decorations and prominence of its position, it’s hard to reach any other conclusion.”

After Herod

According to the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: Herod's kingdom did not endure beyond his death in 4 B.C. With the consent of the emperor, he had divided his realm among his three sons, which proved ungainly and ineffective and which led to unrest. Once again the emperor reorganized Judea as a Roman province governed by a non-Jewish administrator. Although the Sanhedrin was allowed to reassemble as the supreme religious and judicial body of the Jews, heavy taxes and the presence of Roman troops in Jerusalem continued to cause discontent. [Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s Encyclopedia.com]

David L. Silverman of Reed College wrote: “When Herod died in 4 BC, he left behind a country divided. The difficulty is to separate and identify the motives for the violent upheavals which followed the demise of the man who had walked the tightrope between pleasing the Romans and pleasing the Jews, both those in Judea and those of the diaspora. In our sources, especially Philo and Josephus, the motive of Jewish nationalism, closely linked to outrage at the defilement of religious symbols and practices, is foremost. So we are told that the first thing which happened when word leaked that Herod lay dying was that a small band of pious individuals pulled down the golden eagle from its place above the Temple entrance and chopped it to pieces. But piety and nationalism do not tell the whole story. [Source: David L. Silverman, 1996, Internet Archive, Reed College /+/]

Herod coin “Some of those who rioted or led opposition movements after Herod's death were grasping the opportunity for economic gain, exploiting the economic tensions created by Herod's adherence to the Roman approach to the redistribution of wealth, whereby the ordinary citizens were expected to derive satisfaction from seeing public monies spent on lavish building projects. Marxist historians emphasize the recurrent phenomenon of the sicarii, Robin Hood style outlaws whom Herod had repeatedly tried to suppress, and who resurfaced with a vengeance in 4 BC. Many Jews also recalled that Herod and his sons, among whom the kingdom was partitioned after his death, were only Idumeans, residents of a Negev desert region south of Judea whose inhabitants had been converted wholesale to Judaism in the 120's BC; those of the Sadduccees who had resisted cooperating, first with the Hasmoneans and then with Herod, saw their opportunity to regain control of the high priesthood. Some pretenders to the throne in 4 BC, Simon and Athronges, were seekers after personal power, not manifestations of anti-Roman feeling. /+/

Herod’s Successors

David L. Silverman of Reed College wrote: “Herod's attempts to ensure his succession were every bit as messy as those of his counterpart in Rome. No fewer than three separate wills were produced. At first the eldest son, Archelaus, hoped to succeed to the entire realm; but his claim was contested by his brothers Antipas and Philip. While Archelaus and Philip were at Rome presenting their claims to Augustus and the Senate, the country was left in turmoil, exacerbated by the ineptitude of the Roman procurator Sabinus, who burned the Temple at Jerusalem. The governor of Syria, P. Quinctilius Varus, had to bring in troops to quell the riots. Finally Augustus, who had intially shown reluctance to choose among the competing claims beyond firmly rejecting a delegation of anti-Herodians wanting self-government, decided to uphold Herod's third will. The lion's share of the kingdom went to Archelaus, who ruled Judea, Samaria, and Idumea ... but at Roman insistence his title was "ethnarch" rather than king. Lesser realms fell to the other two sons, Antipas and Philip. [Source: David L. Silverman, 1996, Internet Archive, Reed College /+/]

Herod Archelaus

“Archelaus proved a poor choice. Extremely unpopular with the Jews, he exemplified all the worst of his father's qualities, and even the even-handed Josephus has little good to say of him. By 6 AD matters had come to a head, and in the wake of further riots (prompted in part by the attempt of the Syrian legate Quirinus to conduct a census) a delegation from Judea managed to persuade Augustus and the Senate to oust Archelaus. The areas administered by the other sons of Herod continued for the moment as client kingdoms, but Judea and Samaria were annexed to the province of Syria and placed under the oversight of imperial prefects (not called procurators until after 44, as epigraphical evidence shows). The first four of these, Coponius (6-9), Marcus Ambibulus (9-12), Annius Rufus (12-15), and Valerius Gratus (15-26) left no special mark; even Josephus has little to say about them, and we gather that they were for the most part respectful of Jewish idiosyncracies. With the fifth procurator the situation worsens. /+/

“Quite apart from Pontius Pilate's complicity in the crucifixion of Jesus, there is ample evidence to show that he took a high-handed line to the government of his province. Christian writers noted that he had suppressed a riot by massacring a group of Galileans, and accused him of worse (Luke 13:1 "At that very time there were some present who told him about the Galileans whose blood Pilate had mingled with their sacrifices"). For the Jews Pilate's worst offense was belittling the taboo against graven images by introducing military standards into the city, and depositing golden shields inscribed with the name of Tiberius, imperial cult objects in other words, in the palace of Herod. As Philo tells it, Pilate worried about the Jewish protest over the shields, because he feared that if they actually sent an embassy they would expose the rest of his conduct as governor by stating in full the briberies, the insults, the robberies, the outrages and wanton injuries, the executions without a trial constantly repeated, the ceaseless and supremely grievous cruelty (Philo Emb. 302). Indeed, an embassy to Tiberius eventually succeeded in procuring the ouster of Pilate, which shows continuing concern on the part of the imperial administration for keeping the Jews happy. /+/

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons, Schnorr von Carolsfeld Bible in Bildern, 1860

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, Live Science, Archaeology magazine, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024