MESOPOTAMIAN FUNERALS

procession in Ur Proper burials and care of the dead was important to the Mesopotamians, who believed that if the dead were not well taken care of they might come back and haunt their living relatives. The dead who were not given proper burials were believed to be unable to rest in peace in the Underworld and this who were not given regular food offerings went hungry. Only the lowest of the low were denied funerals: criminals, or women who had abortions or died in childbirth.

In some city states (Surghal, El-Hibba, pre-Sargonic Nuppur) cremations were common. In others (Ur and Ashur) they were rare. When a Sumerian monarch conquered a city sometimes the first thing he did was open the graves and release the souls of the dead to drive away enemy soldiers who had not been killed.

Little is known about what Mesopotamia funerals were like. Describing the imagined funeral of a Sumerian royal, the British archaeologist Leonard Woolley wrote: "Now down the sloping passage comes a procession of people, the members of the court, soldiers, men-servants, and women, the later in all their finery of brightly-colored garments and headdresses of lapis-lazuli and silver and gold and with musicians bearing harps or lyres...Each man or woman brought a little cup...Some kind of service there must have been at the bottom of the shaft, at least it is evident that the musicians played up the last, and that each drank from the cup."

The Babylonian corpse was burned as well as buried, and the brick sepulchre that was raised above it adjoined the cities of the living. The corpse was carried to the grave on a bier, accompanied by the mourners. Among these the wailing women were prominent, who tore their hair and threw dust upon their heads. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

”Living and Dying in Mesopotamia” by Alhena Gadotti, Alexandra Kleinerman (2024) Amazon.com;

“Toward a New Understanding of Iraq's Royal Cemetery of Ur” by Andrew C. Cohen (2005) Amazon.com;

“Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion” by Thorkild Jacobsen (1976) Amazon.com;

“Anunnaki Gods: The Sumerian Religion” by Joshua Free Amazon.com;

“A Handbook of Ancient Religions” by John R. Hinnells (2007) Amazon.com;

“Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary” by Jeremy Black (1992) Amazon.com;

“The Heavenly Writing: Divination, Horoscopy, and Astronomy in Mesopotamian Culture” by Francesca Rochberg Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamian Cosmic Geography” by Wayne Horowitz (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Social World of the Babylonian Priest” by Bastian Still (2019) Amazon.com

Burial Customs in Mesopotamia

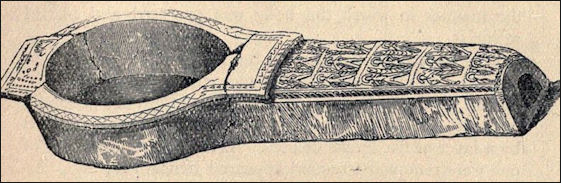

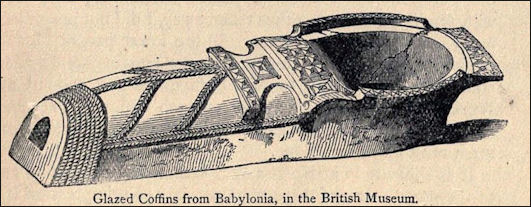

The Assyrians preserved corpses in honey.Early types of Babylonian coffins were bath-tube shaped. Later ones were slipper-shaped coffins. Those from the Persian period frequently have glazed covers with ornamental designs. The coffins may be regarded as typical of the mode of burying the dead in coffins in Babylonia and Assyria, though various other modes existed as well. Excavations in Nippur, Assyria and Babylonia have uncovered graves vaulted in by brick walls. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

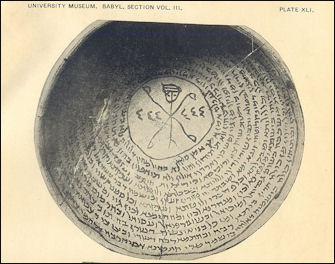

Incantation bowl from Nippur Morris Jastrow said: “Proper burial is, therefore, all essential, even though it can do no more than secure peace for the dead in their cheerless abode, and protection for the living by preventing the dead from returning in gaunt forms to plague them. Libations are poured forth to them at the grave, and food offered by sorrowing relatives. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“The greatest misfortune that can happen to the dead is to be exposed to the light of day; far down into the Assyrian period we find this exemplified in the boast of Ashurbanapal that he had destroyed the tombs of the kings of Elam, and removed their bodies from their resting-place. The corpses of the Babylonians who took part in a rebellion, fomented by his treacherous brother Shamash-shumukin, Ashurbanapal scattered, so he tells us, “like thorns and thistles” over the battle-field, and gave them to dogs, and swine, and to the birds of heaven. At the close of the inscriptions on monuments recording the achievements of the rulers, and also on the so-called boundary stones, recording grants of lands, or other privileges, curses are hurled against any one who destroys the record; and as a part of these curses is almost invariably the wish that the body of that ruthless destroyer may be cast forth unburied.

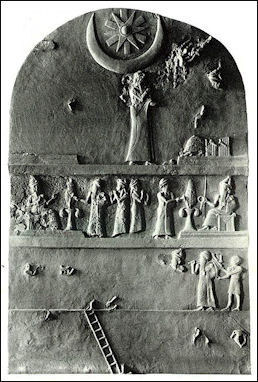

“Mutilation of the corpses of foes, so frequently emphasised by Assyrian rulers, is merely another phase of this curse upon the dead. On one of our oldest pictorial monuments, portraying and describing the victory of Eannatum, the patesi of Lagash (ca . 3000 B.C.), over the people of Umma, the contrast between the careful burial of the king’s warriors, and the fate allotted to the enemy is shown by vultures flying off with heads in their beaks.

“Proper burial is, therefore, all essential, even though it can do no more than secure peace for the dead in their cheerless abode, and protection for the living by preventing the dead from returning in gaunt forms to plague them. Libations are poured forth to them at the grave, and food offered by sorrowing relatives. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“The monument is of further interest in depicting the ancient custom of burying the dead unclad, which recalls the words of Job (i., 21),“naked came I out of my mother’s womb and naked shall I return thither,” which may be an adumbration of this custom. To this day, among Mohammedans and orthodox Jews, the body is not buried in ordinary clothes but is merely wrapped in a shroud; this custom is only a degree removed from the older custom of naked burial. Whether or not in Babylonia and Assyria this custom was also thus modified as a concession to growing refinement, we do not know, but presumably in later times the dead were covered before being consigned to the earth.

“There are also some reasons for believing that, at one time, it was customary to sew the dead in bags, or wrap them in mats of reeds. At all times, however, the modes of burial retained their simplicity. If from knowledge derived from later ages we may draw conclusions for earlier ages, it would seem that the general custom was to place the dead in a sitting or half-reclining posture, on reed mats, and to cover them with a large jar or dish, or to place them in clay compartments having the shape of bath-tubs. The usual place of burial seems to have been in vaults, often beneath the houses of the living. In later periods, we find the tubs replaced by the long slippershaped clay coffins, with an opening at one end into which the body was forced. Throughout these various customs a desire is indicated not merely to bury the body, but to imprison it safely so as to avoid the danger of a possible escape. Weapons and ornaments were placed on the graves, and also various kinds of food, though whether or not this was a common practice at all periods has not yet been determined.

The Stele of E-annatum, Patesi (and King) of Lagash (c . 2900 B.C.) Is a remarkable limestone monument carved on both sides with designs and inscriptions. It was found at Telloh in badly mutilated condition but careful study of its recovered pieces reveals that it represents the conquest of the people of Umma by Eannatum, and records the solemn agreement made between Eannatum and the people of Umma. The upper piece represents vultures flying off with the heads of the slain opponents—to illustrate their dreadful fate. These dead are shown in the second figure, while in the third others who have fallen in battle are carefully arranged in groups and a burial mound is being built over them by attendants who carry the earth for the burial in baskets placed on their heads. Traces of a ceremonial offering to the dead are to be seen in another fragment. The designs on the obverse are symbolical—the chief figure being the patron deity, Ningirsu with the eagle on two lions as the emblem of the god (see Pl. 5, Fig. 1) in his hand, and the net in which the deity has caught the enemies.

Babylonian coffin

Mesopotamian Offerings and Care of the Dead

The dead were believed to have the power to bless and curse their descendants and brings them or deny them children. Therefore their graves were tended and regular offerings of milk, butter, grain and beer were made to them on perhaps a monthly basis.One cuneiform tablet described the care an Assyrian king gave his father read: “In royal oil, I caused him to rest in goodly fashion. The opening of the sarcophagus, the place of rest, I sealed with strong bronze and uttered a powerful spell over it. Vessels of gold, silver and all the [accessories] of the grave, his royal ornaments which he loves, I displayed them before Shamash [the sun god] and placed them in the grave with the father, my begetter. I presented presents to the princely Anunnaki [judges] and the (other) gods that inhabit the underworld.”

When the corpse reached the cemetery it was laid upon the ground wrapped in mats of reed and covered with asphalt. It was still dressed in the clothes and ornaments that had been worn during life. The man had his seal and his weapons of bronze or stone; the woman her spindlewheel and thread; the child his necklace of shells. In earlier times all was then thickly coated with clay, above which branches of palm, terebinth, and other trees were placed, and the whole was set on fire. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

At a more recent period ovens of brick were constructed in which the corpse was put in its coffin of clay and reeds, but withdrawn before cremation was complete. The skeletons of the dead are consequently often found in a fair state of preservation, as well as the objects which were buried with them. While the body was being burned offerings were made, partly to the gods, partly to the dead man himself. They consisted of dates, calves and sheep, birds and fish, which were consumed along with the corpse. Certain words were recited at the same time, derived for the most part from the sacred books of ancient Sumer. After the ceremony was over a portion of the ashes was collected and deposited in an urn, if the cremation had been complete. In the later days, when this was not the case, the half-burnt body was allowed to remain on the spot where it had been laid, and an aperture was made in the shell of clay with which it was covered. The aperture was intended to allow a free passage to the spirit of the dead, so that it might leave its burial-place to enjoy the food and water that were brought to it.

Different Funeral Customs in Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia

Morris Jastrow said: “In general, it may be said, the tombs of the Babylonians and Assyrians were always exceedingly simple, and we find no indications whatever that even for monarchs elaborate structures were erected as their resting-place. Herein Babylonia and Assyria present a striking contrast to Egypt, which corresponds to the difference no less striking between the two nations in their conceptions of life after death. In Egypt, the preservation of the body was a condition essential to the well-being of the dead, whereas in Babylonia a mere burial was all-sufficient and no special care was taken to keep the body from decay. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“The elaborate mortuary ceremonial in Egypt finds no parallel in the Euphrates Valley, where the general feeling appears to be that for the dead there was not much that could be done. Such customs as were observed were prompted, as has been said, rather by a desire to protect the living from being annoyed or tortured by the shades of the unburied or neglected dead. That this fear was genuine is indicated by the belief in a class of demons, known as etimmu, which means the “shade” of a departed person. This conception is best explained as a survival of primitive beliefs found elsewhere, which among many people in a stage of primitive culture led to a widespread and complicated ancestor worship. That this worship existed in Babylonia also is highly probable, but it must have died out as part of the official cult before we reach the period for which we have documentary material; we find no references to it in the ritual texts

Sumerian Burial and Tombs

The Sumerians buried their dead in baskets woven from plaited twigs and in brick coffins held together with bitumen. The graves were regularly arranged, like those in cemetery lots, with streets and lanes. Some graves, dated at between 2600 and 2000 B.C., consisted of pits with two-meter-high walls lined with coarse reed matting. The dead were rapped in the reed matting or placed in coffins made of matting, wickerwork, wood or clay.

The Sumerians often buried their dead with their most prized objects. Even commoners were buried with objects they thought they would need in the Underworld. Most of the Sumerian works of art have been excavated from graves. Royal tombs have revealed treasures made with gold and precious stones while commoners were mostly buried with stone figurines.

Babylonian coffin

Dead people were buried with food because it was believed that undernourished corpses would return as ghosts. Graves from the Ubaid period, dated to 5200 B.C., contained skeletons with hands crossed over their pelvis and accompanied by vessels of food and drink and weapons. Some Akkadian graves contain skeletons with their hand holding cups near their faces.

Umma al-Ajarib is the largest known Sumerian cemetery. Located about 400 kilometers south of Baghdad, it is spread out over an area of five square kilometers and is believed to contain hundreds of thousands of graves. The name of the cemetery means “Mother of Scorpions” due to the large number of scorpions that live there. Many graves have been looted by grave robbers. More would have been, some have speculated, if it weren’t for the scorpions.

Eridu in southern Iraq contains a Sumerian burial ground that covers an area of about one square kilometer. About a thousand graves have been excavated there so far. In the 2nd millennium it became common to place deceased family members in a pit or a brick vault buried beneath the house where the family lived. One reason for this is that it made care of the dead easier.

Tombs of Sumerian Royals

The Royal Tombs at Ur (circa 2600 B.C.) consisted of a vaulted or domed chamber at the bottom of a deep pit, which was a approached from the outside by a ramp. The largest chambers were stepped or sloped shafts as deep as 30 feet underground and 40 by 28 feet.

The royal tombs of Ur contained musical instruments and draft animals yoked to carts. In Ashur the tombs were below a large palace and the dead were placed in stone sarcophagi. The deceased was placed in wooden coffins or placed on a wooden bier, and provided with clothing, games, weapons, treasures and vessels with food and drink.

Rich rulers were buried with precious objects for a trip to the afterlife. Queen Pu-abi was buried in the most elaborate Mesopotamian tomb ever found. It contained jewelry, seashells with cosmetics, a four-foot gold drinking straw, pins, wreaths, diadems, gold tweezers, translucent alabaster bowls, foodstuffs and weapons. Sacrificed and buried with her were oxen, handmaidens, musicians and servants. She was identified by a cylinder seal pinned to her sleeve.

Some of the most spectacular Sumerian art was unearthed from the grave of Queen Pu-abi, a 4,600-year-old site excavated by British archaeologist Leonard's Woolleys' team in Ur. The pieces found there included lyres decorated with golden bull heads and a wiglike helmet of gold described above as well as earrings, necklaces, a gold dagger with a filigree sheath, a toilet box with a shell relief of lion eating a wild goat, inlaid wooden furniture, a golden tumbler, cups and bowls, and tools and weapons made of copper, gold and silver.

Queen Pu-abi was buried, wearing, a necklace of gold and lapi lazuli, 10 gold rings, garters of gold and lapis lazuli, and a striking cape made of gold, silver, lapis lazuli, agate and carnelian beads. She was buried with 11 other women, presumably her attendants. Queen Pu-abi’s headdress was made of gold ribbons, carnelian and lapis lazuli beads, bands of gold leaves, all surmounted by a high comb of silver with eight-petaled gold rosettes, symbols of goddess Inana.

Archaeologists working at the Queen Pu-abi site also unearthed a mosaic with figures made from limestone, muscle shell and mother of pearl, on a lapis background that shows a military procession with troops driving their chariots over captured enemies.

Human Sacrifice at Royal Burials

from the royal graves The individuals buried in the royal tombs in Ur and Kish were buried with six to 73 “attendants,” who appear to have been ritually killed and interred along with the deceased. The attendants were elaborately dressed and interred in a crouching position, as if waiting to provide service. Chambers with the “attendants” were placed in positions in relation to the royal chamber that were indicative of their occupations: guards, musicians, grooms, charioteers.

The oldest evidence of mass killings and human sacrifice was found in 1926 in a tomb in Ur, dated to around 4000 B.C. The remains of aristocrats and commoners who had been killed with blows from behind were laid out in rows. Hundreds of graves dating to 2500 B.C. containing human sacrifice victims have been found at Ur and are thought to have been related to deaths of Mesopotamian kings.

When a king or queen died it seems that servants, musicians and family members of kings and queens were killed and buried with them. According to a Sumerian saga “ The Story of Gilgamesh” , King Gilgamesh of Uruk was buried with much of his family.

“ His beloved son

His beloved favorite wife and

junior wife.

His beloved singer.

cup-bearer and his

beloved barber...”

Babylonian Tombs

Babylonian tombs were built of bricks; there were no rocky cliffs in which to excavate them, and the marshy soil made a grave unsanitary. It was doubtless sanitary reasons alone that caused wood to be heaped about the tomb after an interment and set on fire so that all within it was partially consumed. The narrow limits of the Babylonian plain obliged the cemetery of the dead to adjoin the houses of the living, and cremation, whether partial or complete, became a necessity. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Unlike Egyptians, Babylonians had no desert close at hand in which to bury their dead. It was necessary that the burial should be in the plain of Babylonia, the same plain as that in which he lived, and with which the overflow of the rivers was constantly infiltrating. The consequences were twofold. On the one hand, the tomb had to be constructed of brick, for stone was not procurable; on the other hand, sanitary reasons made cremation imperative. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Over the whole a tomb was built of bricks, similar to that in which the urn was deposited when the body was completely burned. The tombs of the rich resembled the houses in which they had lived on earth and contained many chambers. In these their bodies were cremated and interred. Sometimes a house was occupied by a single corpse only; at other times it became a family burial-place, where the bodies were laid in separate chambers. Sometimes tombstones were set up commemorating the name and deeds of the deceased; at other times statues representing them were erected instead.

The tomb had a door, like a house, through which the relatives and friends of the dead man passed from time to time in order to furnish him with the food and sustenance needed by his spirit in the world below. Vases were placed in the sepulchre, filled with dates and grain, wine and oil, while the rivulet which flowed beside it provided water in abundance. All this was required in that underworld where popular belief pictured the dead as flitting like bats in the gloom and darkness, and where the heroes of old time sat, strengthless and ghostlike, on their shadowy thrones.

Babylonian Cemeteries

The cemetery to which the Babylonian dead was carried was a city in itself, to which the Sumerians had given the name of Ki-makh or “vast place.” It was laid out in streets, the tombs on either side answering to the houses of a town. Not infrequently gardens were planted before them, while rivulets of “living water” flowed through the streets and were at times conducted into the tomb. The water symbolized the life that the pious Babylonian hoped to enjoy in the world to come. It relieved the thirst of the spirit in the underground world of Hades, where an old myth had declared that “dust only was its food,” and it was at the same time an emblem of those “waters of life” which were believed to bubble up beneath the throne of the goddess of the dead. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

The houses and tombs were alike constructed of sun-dried bricks, which soon disintegrate and form a mound of dust. A shortage of space caused the tombs of the dead to be built one upon the other, as generations passed away and the older sepulchres crumbled into dust. The cemetery thus resembled the city; here, too, one generation built upon the ruins of its predecessor.

The age of a cemetery, like the age of a city, may accordingly be measured by the number of successive layers of building of which its mound or platform is composed. In Babylonia they are numerous, for the history of the country goes back to a remote past. Each city clustered round a temple, venerable for its antiquity as well as for its sanctity, and the cemetery which stood near it was consequently under the protection of its god. At Cutha the necropolis was so vast that Nergal, the god of the town, came to be known as the “lord of the dead.” But the cemeteries of other towns were also of enormous size. Western Asia had received its culture and the elements of its theology from Babylonia, and Babylonia consequently was a sacred land not only to the Babylonians themselves, but to all those who shared their civilization.

The very soil was holy ground; Assyrians as well as Babylonians desired that their bodies should rest in it. Here they were in the charge, as it were, of Bel of Nippur or Marduk of Babylon, and within sight of the ancient sanctuaries in which those gods were worshipped. This explains in part the size of the cemeteries; the length of time during which they were used will explain the rest.

As Dr. John Peters says of each: “It is difficult to convey anything like a correct notion of the 4 piles upon piles of human relics which there utterly astound the spectator. Excepting only the triangular space between the three principal ruins, the whole remainder of the platform, the whole space between the walls, and an unknown extent of desert beyond them, are everywhere filled with the bones and sepulchres of the dead. There is probably no other site in the world which can compare with Warka in this respect.” Babylonia is still a holy land to the people of Western Asia. The old feeling in regard to it still survives, and the bodies of the dead are still carried, sometimes for hundreds of miles, to be buried in its sacred soil. Mohammedan saints have taken the place of the old gods, and a Moslem chapel represents the temple of the past, but it is still to Babylonia that the corpse is borne, often covered by costly rugs which find their way in time to an American or European drawing-room. “The old order changes, giving place to new,” but the influence of Chaldean culture and religion is not yet past.

Royal Tombs

Mesopotamian kings were allowed to be burned and buried in the palace in which they had lived and ruled. We read of one of them that he was interred in “the palace of Sargon” of Akkad, of another that his burial had taken place in the palace he himself had erected. A similar privilege was granted to their subjects only by royal permission. [Source: “Babylonians And Assyrians: Life And Customs”, Rev. A. H. Sayce, Professor of Assyriology at Oxford, 1900]

Stela of Ur-Nammu In 1988 Iraqi archaeologist Muzahem Hussein uncovered two 8th century B.C. tombs under the royal palace in Nimrud. He discovered the site when he realized he was standing on some great vaults while putting some bricks back in place After two weeks of clearing away dirt and debris he caught his first glimpse of gold. The treasure that was found was on display for just a few months before the 1991 Persian Gulf War, when it was packed away for protection and put in a vault beneath Baghdad’s central bank . Though the bank was bombed, burned and flooded during the 2003 invasion of Iraq the treasure reportedly was undamaged.

The first tomb was still sealed and contained a woman who was 50 or so and a collection of beautiful jewelry and semiprecious stones. A second tomb, about 100 meters away, contained the two women, perhaps queens. They were placed in the same sarcophagus one on top of the other, wrapped in embroidered linen and covered with gold jewelry. One of the women had been dried and smoked at temperatures of 300 to 500 degrees, the first evidence of mummification-like practices in Mesopotamia.

The second tomb contained a curse, threatening the person who opened the grave of Queen Yaba (wife of powerful Tiglthpilese II (744-727 B.C.) with eternal thirst and restlessness, with a specific warning about placing another corpse inside. The curse was written before the second corpse was placed inside. The two women inside were 30 to 35 years of age, with the second being buried 20 to 50 year after the first. The first is thought to be Queen Yaba. The other is thought to be the person identified by a gold bowl found inside the sarcophagus that reads: “Atilia, queen of Sargon, king of Assyria: who rule from 721 ro 705 B.C.”

A third tomb excavated in 1989 had been looted but looters missed an antechamber that contained three bronze coffins: 1) one with six people, a young adult, three children, a baby and a fetus.; 2) another with a young woman, with a gold crown, thought to have been a queen; and 3) a third with a 55- to 60-year-old man, and a golden vessel that appears to have identified him as a powerful general that served under served several kings.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024