Home | Category: Neo-Babylonians / Hebrews in Babylon and Persia / Hebrews in Babylon and Persia

EXILE OF THE JEWS AFTER THE NEO-BABYLONIAN CONQUEST (587-538 B.C.)

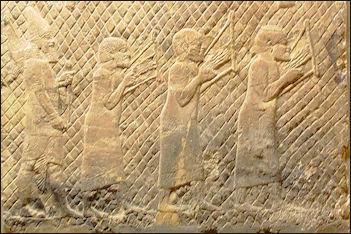

Captive Israelites In 587 B.C. the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem was destroyed by the Babylonians, the Jewish leadership was killed. This resulted in the exile of most of the Israelite nobility and leadership. Many Jews were sent into exile in Babylon.

More precisely, in 587 BC, the Neo- Babylonians (Chladeans), under King Nebuchadnezzar II, destroyed Jerusalem, the capital of the Kingdom of Judah, and the Temple of Jerusalem — the "House of God" — built by King Solomon, as the centrepiece of Jewish faith. The Biblical books of 2 Chronicles and 2 Kings describes how the Neo-Babylonians took the elite of the Jewish people into captivity. Psalm 137:1 records the anguish of the captives: "By the rivers of Babylon we sat and wept, when we remembered Zion". After the Neo-Babylonian empire was defeated by the Persians from modern Iran, the prophets Ezra and Nehemiah led a minority of Jewish exiles back to Jerusalem, motivated by an ancient version of Zionism. [Source: Huffington Post, February 3, 2015]

Key Events of the Exile Period

587/586 B.C.: Southern Kingdom (Judah) and First Temple destroyed-Babylonian exile

ca. 550 B.C.: Judean Prophet “Second Isaiah”

541 B.C.: First Jews return from Babylon in small numbers to rebuild the city and its walls. Seventy years of exile terminated. (Daniel 9, Haggai 2:18-19)

539 B.C.: Persian ruler Cyrus the Great conquers Babylonian Empire

[Source: Jewish Virtual Library, UC Davis, Fordham University]

Relevant sections of the Bible

Number of Exiles (4,600): Jeremiah 52:28-30

In Babylon, Psalm 137

Cyrus as Liberator, 539 BCE, Isaiah 45

Kurash (Cyrus) the Great: The Decree of Return for the Jews, 539 BCE

[Source: sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

Websites and Resources: Virtual Jewish Library jewishvirtuallibrary.org/index ; Judaism101 jewfaq.org ; torah.org torah.org ; Chabad,org chabad.org/library/bible ; Bible and Biblical History: ; Biblical Archaeology Society biblicalarchaeology.org ; Bible History Online bible-history.com Bible Gateway and the New International Version (NIV) of The Bible biblegateway.com ; King James Version of the Bible gutenberg.org/ebooks ; Jewish History: Jewish History Timeline jewishhistory.org.il/history Jewish History Resource Center dinur.org ; Center for Jewish History cjh.org ; Jewish History.org jewishhistory.org ; Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Nebuchadrezzar and Babylon” (Schweich Lectures on Biblical Archaeology)

by D. J. Wiseman Amazon.com ;

“Synchronized Chronology: for the Ancient Kingdoms of Israel, Egypt, Assyria, Tyre, and Babylon” by Dan Bruce Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jewish People During the Babylonian, Persian, and Greek Periods”by Charles Foster Kent Amazon.com ;

“Twelve Tribes of Israel” by Rose Publishing Amazon.com ;

“The Myth of the Twelve Tribes of Israel” by Andrew Tobolowsky Amazon.com ;

“The Kings and Prophets of Israel and Judah: From the Division of the Kingdom to the Babylonian Exile (Classic Reprint)” by John Foster Mitchel Amazon.com ;

“The Temple of Solomon” by Kevin J. Conner Amazon.com ;

“Why the Bible Began: An Alternative History of Scripture and its Origins” by Jacob L. Wright Amazon.com ;

“NIV, Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible (Context Changes Everything) by Zondervan, Craig S. Keener Amazon.com ;

“Oxford Companion to the Bible” by Bruce M. Metzger and Michael David Coogan Amazon.com ;

“Historical Atlas of the Holy Lands” by K. Farrington Amazon.com ;

“The Story of the Jews” Volume One: Finding the Words 1000 BC-1492 AD by Simon Schama (Author) Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jews” by Paul Johnson, Amazon.com

Exile of the Jews and the Jewish Diaspora

Assyrian Prisoners In 539 B.C., the Persian king Cyrus, who had defeated the Neo-Babylonian armies, gave the exiles permission to return. Many, however, remained in Babylonia, which, together with Egypt, where Jews had also voluntarily settled, became the first community of the Diaspora. Those who did return found a Temple in ruins and, according to The Bible, a dispirited people, without spiritual leadership, who had turned their backs on the laws of the Torah and had mixed with non-Hebrews and adopted some of their non-monotheist religious practices.

The Jews that stayed in exile marks the beginning the Jewish tradition of the Diaspora —living away from Israel. It was also apparently during the Babylonian Exile that the institution of the synagogue as a house of prayer began to emerge. During the centuries that followed the conquests by the Neo-Babylonians, the Jewish state fell under the auspices of various empires such as Persia, Hellenistic Greece and Rome. It was a bit like an ethnic state like Turkmenistan or Armenia in the Soviet Union, or a colony like pre-World War II India or Algeria.

Despite many warnings, according to the Bible, the Jews had not fulfilled their end of the bargain in regards to the Covenant and were punished by their exile into Bablyonia. Through penitence their kingdom was to be restored. This never really took place and gave birth to ideas about a messiah. When Jewish followers asked their priests why God had not kept his promise with David and their state disappeared so quickly, the priests told the followers that they had sinned and broke their agreement with God. They were told that once they had repented and been forgiven for their sin, God would sent a new leader, a messiah. The understanding was that this messiah would be a David-like military leader who would defeat the Jews’ enemies and oppressors in great battles.

Nebuchadnezzar and the Exile of the Jews In Babylon

Nebuchadnezzar, the powerful ruler famed for the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, came to Jerusalem several times as he sought to spread the reach of his kingdom. Each time he came — and one visit coincided with the destruction of Jerusalem’s first temple in 586 BC — he either forced or encouraged the exile of thousands of Judeans. One exile in 587 BC saw around 1,500 people make the perilous journey via modern-day Lebanon and Syria to the fertile crescent of southern Iraq, where the Judeans traded, ran businesses and helped the administration of the kingdom. “They were free to go about their lives, they weren’t slaves,” Filip Vukosavovic, an expert in ancient Babylonia, Sumeria and Assyria, told Reuters. “Nebuchadnezzar wasn’t a brutal ruler in that respect. He knew he needed the Judeans to help revive the struggling Babylonian economy.” [Source: Luke Baker, Reuters, February 4, 2015]

After Nebuchandnezzar captured Jerusalem in 586 B.C. many Jews were sent to Babylonia, which was ruled by the Chaldean Empire. According to the Bible the Babylonian King Belshazzar hosted a feast with 1,000 courtiers and their wives during the captivity of the Jews. Golden and silver vessels taken from the Temple in Jerusalem were used to drink wine and make toasts. On some of the vessels appeared the words, “God hath humbled thy kingdom, and finished it. Thou art weighed in the balances, and art found wanting. Thy kingdom is divided, and given to the Medes and Persians." All these prophesies came true.

The Jews were held captive by the Babylonians from 586 B.C. to 537 B.C. But rather than dying out or being assimilated the Jews kept their identity and religion alive through reverence of the Torah. The first synagogue are believed to have been built during the Babylonian Exile when Jews were unable to reach the Jerusalem Temple.

See Separate Article: NEBUCHADNEZZAR II (RULED 604-561 B.C.), HIS CONQUESTS AND THE BIBLE africame.factsanddetails.com

destruction of Solom's Temple and the exile of the Jews

Two Parts of the Exile Period

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “THE Exilic period falls into two parts: the years between 597 and 586 and the years after 586 up to 538 or 537. The mood and mind set of the people of Judah during the first period seems to have been one of continuing hope. In the second period, from the meagre sources available, despondency and humble acceptance of their tragic conditions appears to have characterized the remnant in Judah. Up until 586, so long as the temple-the symbol of Yahweh's power-was intact, and so long as Jerusalem itself, perhaps somewhat battered by the Babylonian siege, was still standing, a "business as usual" atmosphere seems to have prevailed. Jeremiah's preaching indicates that oppression of the poor, exploitation, apostasy-those evils which the prophet said provoked Yahweh to anger-were unchecked. There is no evidence of serious concern about further danger to national welfare. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

“When Babylonian forces returned in 587, some Judaeans fled to Egypt (II Kings 25:25 f.; Jer. 42 f.) and settled at Tahpanhes, or Daphnae, a border fortress in northern Egypt believed to be located at modern Tell Defneh. Concerning the fate of these migrants we know nothing, but from a later period we have knowledge of a Jewish military colony at Elephantine, the town guarding the southern Egyptian border near the first cataract of the Nile. Fifth century papyri from this site mention a Jewish temple dedicated to Yahweh (spelled Yahu or Yaho) and possibly to two other deities, although the evidence is not clear.1 It is possible that the colony was founded between 598 and 5872 and may have included Jews fleeing Judah prior to the fall of Jerusalem. Some Jews sought sanctuary in Moab, Ammon and Edom (Jer. 40:11), but no information is available about these refugees.

Jewish Captives in Babylon

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “Jewish captives in Babylon no doubt suffered hardships, but Jeremiah's letter implies that they lived in a village where they could build private dwellings and cultivate the soil. No restrictions seem to have been placed on marriage or worship (Jer. 29). Hope was strong for a speedy return to Jerusalem, and so long as the temple remained, it must have been assumed that Yahweh had punished his people but had not forsaken them. More information about this period comes from Ezekiel whose prophetic work extends from the first deportation into the period following the destruction of Jerusalem. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

“What impression the magnificent city of Babylon made upon the exiles can only be imagined. Nebuchadrezzar had made Babylon into one of the most beautiful cities in the world. This great metropolis straddled the Euphrates and was surrounded by a moat and huge walls 85 feet thick with massive reinforcing towers. Eight gates led into the city, the most important being the double gate of Ishtar with a blue facade adorned with alternating rows of yellow and white bulls and dragons. Through the Ishtar gate a broad, paved, processional street known as "Marduk's Way" passed between high walls, past Nebuchadrezzar's palace and the famous "hanging gardens" to the ziggurat of Marduk, the national god. This tremendous brick structure named E-temen-an-ki, "the House of the Foundation of Heaven and Earth," was 300 feet square at the base and rose in eight successive stages to a height of 300 feet. Temples dedicated to various gods and goddesses abounded. Beyond the city were lush orchards, groves and gardens, fed by an intricate canal system, from which supplies of fruits and vegetables were obtained. Domesticated animals, fish, wild fowl and game provided a varied diet. From east and west, north and south, came caravans with goods for trade and barter. In festal seasons, sacred statuary from shrines in nearby cities was brought to Babylon by boat and land vehicles. Truly Babylon was, as her residents believed, at the "center" of the world. The magnificent splendor of the city must have impressed the Jews, and as we shall see, there is some evidence that Babylonian religious concepts also made an impression on the exiles.

“Some Judaeans were held as hostages within the city proper and among these were Jehoiachin, the exiled king, and his family. Tablets discovered in the excavation of the city and dated between 595 and 570 include lists of rations paid in oil and barley from the royal storehouses to captives and skilled artisans from Egypt, Ashkelon, Phoenicia, Syria, Asia Minor and Iran.

Specifically mentioned were "Yaukin, king of the land of Yahud" (Jehoiachin of Judah), his five sons, and eight other Judaeans. It is important to note that Jehoiachin was still called "King of Judah." Royal estates in Judah were managed, at least up until 586, by "Eliakim, steward of Jehoiachin," whose seal impressions have been found in excavations at Debir and Beth Shemesh. “The immediate impact of the news of the fall of Jerusalem upon the exiles must have produced shock and horror. But, as we shall see from the literature, there developed a new hope for restoration, a new discovery of the meaning of election and covenant, and a new sense of destiny, which grew in strength and excitement until something of a triumphant climax is reached in the writings of Deutero-Isaiah. Not all exiles responded to the new concepts and some of Isaiah's words castigate these blind, unresponsive ones, but as it is impossible today to read, unmoved, the stirring, inspiring words preserved from those times, it is quite reasonable to imagine that there must have been those roused to peaks of hope and encouragement as they contemplated the future.

Ancient Tablets Reveal Life of Jews in Nebuchadnezzar's Babylon

Ancient clay tablets discovered in Iraq and shown to the public for the first time at an exhibition in Jerusalem in 2015 revealed information for the first time on the daily life of Jews exiled to Babylon some 2,500 years ago. Luke Baker of, Reuters wrote: “The exhibition is based on more than 100 cuneiform tablets, each no bigger than an adult’s palm, that detail transactions and contracts between Judeans driven from, or convinced to move from, Jerusalem by King Nebuchadnezzar around 600 BC. [Source: Luke Baker, Reuters, February 4, 2015 -]

“Archaeologists got their first chance to see the tablets — acquired by a wealthy London-based Israeli collector — barely two years ago. They were blown away. “It was like hitting the jackpot,” said Filip Vukosavovic, an expert in ancient Babylonia, Sumeria and Assyria who curated the exhibition at Jerusalem’s Bible Lands Museum. “We started reading the tablets and within minutes we were absolutely stunned. It fills in a critical gap in understanding of what was going on in the life of Judeans in Babylonia more than 2,500 years ago.” -

The tablets, each inscribed in minute Akkadian script, detail trade in fruits and other commodities, taxes paid, debts owed and credits accumulated. The exhibition details one Judean family over four generations, starting with the father, Samak-Yama, his son, grandson and his grandson’s five children, all with Biblical Hebrew names, many of them still in use today. “We even know the details of the inheritance made to the five great-grandchildren,” said Vukosavovic. “On the one hand it’s boring details, but on the other you learn so much about who these exiled people were and how they lived.” -

Vukosavovic describes the tablets as completing a 2,500-year puzzle. While many Judeans returned to Jerusalem when the Babylonians allowed it after 539 BC, many others stayed and built up a vibrant Jewish community that lasted two millennia. “The descendants of those Jews only returned to Israel in the 1950s,” he said, a time when many in the diaspora moved from Iraq, Persia, Yemen and North Africa to the newly created state.” -

Ezekiel on the Exile

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “Among the elite of Judaean society deported by Nebuchadrezzar in 597 was Ezekiel, a son in the priestly family of Buzi (1:3). The Jews were settled on the Kabari canal, or the "river Chebar" as it is called in Ezek. 1:1, which tapped the Euphrates' waters for agricultural and navigational purposes. The initial verses of the Book of Ezekiel, written in autobiographical form, speak of the thirtieth year, but no guidance is given as to the significance of this period which could refer to the thirtieth year of the prophet's life, to the time when the oracles were recorded some thirty years after his first vision, or to the thirtieth year of the Exile. The vocational summons which came in the fifth year of Jehoiachin has been dated July 21, 592.3 [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

Ezekiel's vision

“Innumerable problems are associated with the Book of Ezekiel. The prophet stipulates that he is among the exiles, but his words in Chapters 1 to 24 are addressed to Jews in Jerusalem. May one assume that he was permitted to break his exile and return to Jerusalem-and there is no evidence that this was possible-or did he send his oracles back to the Jerusalemites by courier? For some, his intimate knowledge of events in Jerusalem suggests that he was in that city, for his words had devastating effects upon some hearers there (cf. II: 13-14). Consequently, it has been proposed that Ezekiel prophesied in Palestine and that the Babylonian setting is the result of editing; or that he was exiled to Babylon, received his call there, and then returned to Palestine; or that he spoke in Babylon for the benefit of his hearers there, having received detailed information about events in Palestine by courier or by clairvoyance.4 No clear solution is possible and scholars are divided between a Babylonian and a Palestinian provenance. We will assume that Ezekiel remained in Babylon and that references to his visits to Jerusalem are visionary experiences, perhaps supplemented by his personal memories of the city and by news received from informants from Palestine.

“The integrity of the book has been challenged, with one scholar limiting authentic Ezekiel passages to some 170 verses,5 and others accepting almost the whole book as genuine6 or attempting to identify larger sections containing an Ezekiel core.7 The book has been classified as a third century, pseudonymous story about a priest in the time of Manasseh, which was later edited to provide the Babylonian setting-in which case there would have been no such person as Ezekiel.8 It has also been dated in the time of Manasseh and identified as a northern Israelite work, later edited by someone from Judah and given a Babylonian setting.9 Most scholars accept a sixth century date but recognize that the book was carefully edited, perhaps by the prophet's disciples, so that it is, therefore, very difficult to isolate genuine Ezekiel materials.10 Because of the complexity of this problem, we shall make no attempt to identify genuine Ezekiel passages. The book will be accepted as "Ezekielan" (Ezekiel and his disciples) except where study of the text has made it clear to most scholars that we are dealing with non-Ezekiel intrusions.

Prophets and the Exile

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “As Ezekiel and Job wrestled with the problems of suffering and restoration, other Jews searched for words of hope and guidance in the oracles of the prophets who had predicted the downfall of Israel and Judah. Predictions of doom had been fulfilled; were there other clues that might reveal what Yahweh had in store for his people? It is possible that Hosea's teachings about Yahweh's grace and mercy stimulated hope, and there were those who in the renewed study of Hosea's words added new insights and new promises. Commentaries on the names of Hosea's children, those symbols of Yahweh's rejection of his people (Hos. 1:4-9), were composed. One was affixed to the verses introducing the children (Hos. 1:10-2:1), softening their harshness by the prediction of the restoration of the united kingdom, and the promise that the people would be recognized as "sons of the living God." Another (2:21-23) looked to the days when Yahweh would pity "Not-pitied," accept "Not-my-people" as his own, would bring blessing out of Jezreel and restore the covenant relationships. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org]

Isaiah predicts the return of the Jews from exile

“Prophecies of hope and restoration were appended to the works of other eighth century writers. The last five verses of Amos (9:11-15) envision the restoration of the Davidic kingship (represented in Jehoiachin in exile), the rebuilding of ruined cities and a bounteous future marked by peace and security. To Isaiah's doom oracles were added restoration oracles. Some additions reveal deep and intimate appreciation of Isaiah's style and may represent contributions by the prophet's disciples or school, if such a group can be postulated for the Exilic period.22 Some of Isaiah's harsh predictions are reversed as in the oracles of restoration of 4:2-6 (4:2 cf. 2:13; 4:3 cf. 2:6-8; 4:4 cf. 3:16, 17, 24; 4:6 cf. 2:12 ff.).

“If, as some scholars believe, Isaiah 9:2-7 and 11:1-9 are not by Isaiah of Jerusalem, they may be from the Exilic period. The author of the first poem proclaimed that light was breaking into the darkness of the Exile. He rejoiced in the birth of a child in the royal family, perhaps the prince Zerubbabel who was to play an important role in the post-Exilic period. The exalted names given to the child express the exalted hopes of the writer. Chapter 11:1-9 portrays the ideal king who, like David, would establish the united kingdom of Israel and Judah. He envisions a time of perfect peace under a charismatic ruler of the Davidic line. These poems fit well into the Exilic period when dreams were dreamed of an ideal future, an ideal Davidic kingship and future glory for the Jews.

“Some additions to Isaiah recognized the threatening power of the Median empire on Babylon's eastern flank and anticipated the fall of the Babylonian kingdom (Isaiah 13-14; 21). Other oracles commented on the fall of Moab (15-16), overcome by some unnamed disaster which could have been anything from attacks by desert tribes23 to an invasion by Babylonians.24 Some passages employ vivid imagery in visualizing punishment for the enemy and rise to sublime heights in idealizing the future (chs. 34-35). Additions to Isaiah were not all made at one time. Chapters 34 and 35 are so close in parts to Deutero-Isaiah, in both style and content, that some scholars have proposed that they should be included in that work.

“At least one Exilic poem exalting the restored Zion was added to two prophetic collections and appears in Isaiah 2:2-4 and Micah 4:1-3. Other additions to Micah prophesy the regrouping of the scattered people (2:12-13), the coming of a messianic leader like David (5:2-4, 7) and Yahweh's forgiveness of his people (7:8-20). More recent prophetic pronouncements were also studied. An addition predicting restoration was added to Jeremiah's oracles (Jer. 3:15-18) in which the fact that the ark of the covenant was forever lost is apparent. One composite appendage (Jer. 10:1-16), parts of which are similar in style and content to Deutero-Isaiah, warns against forsaking Yahweh for idols made by artisans. The myth of the return of David which later becomes a basis for messianism is found in an eschatological oracle (30:8-9). Other restoration sayings appear in 31:7-14. An oracle on the fall of Moab, not unlike that found in the additions to Isaiah, may be from the Exile (ch. 48), and other pronouncements of punishment on foreign nations appear to be from the same period (49-51:58).

Lamentations

In the Torah, the book of Lamentations describes the horrors endured by Jerusalem's residents. It is also remembered in verses in the psalms: “O God, the nations have invaded your inheritance: they have defiled your holy Temple, they have reduced Jerusalem to rubble."

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “The effect on Jewish morale of the downfall of the capital city and the destruction of the temple which had symbolized Yahweh's enduring patience and love for nearly 400 years must have been devastating. Only a small collection of five poems, written over a considerable period of time, provides any insight into the shock, horror and grief of the people.

Jeremiah lamenting

“Ancient tradition assigns the authorship of Lamentations to Jeremiah. A prefatory comment in the LXX says the poems are by Jeremiah, possibly on the basis of II Chron. 35:25,26 but modern scholars reject this hypothesis for several reasons. There is no indication in the Hebrew version that Jeremiah was the author, and ideas presented within the poems contradict Jeremiah's teachings. For example, it is highly unlikely that Jeremiah, out of his personal experiences of Yahweh, would state that prophets did not receive visions (Lam. 2:9); nor would the prophet accept the argument that the sins of the past were responsible for the destruction (Lam. 5:7), for he consistently preached that the apostasy of the day would engender divine wrath. The plaintive reminiscence of the hope for deliverance by Egypt (Lam. 4:17) contradicts Jeremiah's dismissal of the possibility of aid from the south. The authors or author remain unknown. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

“The opening word of the collection, "how" (Heb. 'ekah), gives the Hebrew title to the book33 and introduces the dirge form of the poem.34 The desolate city is portrayed as a widow, not dead but alone, forsaken, weeping in the night when none can see. The contrast between the glories of the past introduced in the first verse and the present state portrayed in subsequent verses conveys to the reader the desolation of the city. There is a forthright recognition that Jerusalem's sin caused the downfall, and the imagery of the adulterous woman (1:8-9) is reminiscent of Hosea. The dirge terminates in Verse 11, and an individual lament, written in the first person singular, portrays the city speaking and explaining the tragedy that occurred. Verse 17 returns to the third person singular form and describes Yahweh as the commander of Jerusalem's enemies. The closing verses, a confession of guilt written in the first person singular, portray the unfaithful wife in the days of distress calling for help to her lovers (other gods?) to no avail. The poem closes with an expression of grief and anguish. Because there is a suggestion in the poem that Jerusalem was not completely destroyed, it is possible that these verses were written after 597 but before the collapse of the nation in 586.

“After the temple was destroyed again in A.D. 70 by the forces of the Roman general, Titus, the book of Lamentations was liturgically used on the ninth day of the Jewish month Ab (July-August) to commemorate both the Roman and Babylonian destructions. How far back the liturgical use of Lamentations can be traced is debatable, but Zechariah 8:18-19 suggests fasts associated with the siege and destruction of Jerusalem (cf. II Kings 25:1-4; Jer. 39:2) and Zechariah 7:3 ff. implies a long practice of the custom, dating back to the Exile. A Sumerian poem of similar nature, bewailing the fate of the city of Ur, written during the early part of the second millennium bears striking affinities to the Hebrew poem. It is possible that the Sumerian poem was used in a commemorative ritual, so that the Jewish poet may have composed his laments according to a custom well established and well known in the Near East. It is reasonable to suggest that the poems of Lamentations were employed in a commemorative liturgy during the Exile, with the first person singular portions recited by a leader representing the corporate group or the city and other portions spoken by the congregation.”

Holiness Code

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “During this period of creative productivity, another body of writings, cultic and ethical in nature, took form as the so-called Holiness or H code of Leviticus 17-26. This material takes its title from the repeated emphasis on Yahweh's holiness, best summarized in Lev. 19:2: "You shall be holy, for I, Yahweh your god, am holy". [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

Fall of Babylon by Ottheinrich “Parallels in language, style and content to Ezekiel (cf. Lev. 17:15 with Ezek. 44:31; Lev. 18:8 and 20:11 with Ezek. 22:10, etc.) and the presupposition in Lev. 17:1-9 of the central shrine called for in Deuteronomy, have led many scholars to place H in the Exile, close to the time when Ezekiel was written. Much of the material may have come from an earlier date, but the editing reflects the Exilic period. In its present form, the code parallels Deuteronomy in the hortatory tone that creeps in from time to time (cf. 19:33 f.), and like Deuteronomy, H is said to have been given by Yahweh to Moses at Sinai, and the closing has the familiar pattern of blessings and curses.

“The code is concerned with ritual purity for laity and priests. If Israel was to be the people of Yahweh, care had to be taken not to violate Yahweh's holiness. Numerous apodictic laws and some casuistic rulings seem to be loosely strung together, and despite attempts to isolate small collections or units, no real pattern of sources has been found. The contents are as follows:

“Chapter 17 is concerned with laws of killing for food and sacrifice. As noted above, reference to the central altar suggests acceptance of the Deuteronomic law, but the holiness code is stricter, eliminating the special provisions found in D for slaughter for food when one lives away from the central shrine.25

Chapter 18 sets forth in apodictic form principles governing sexual relations.

Chapter 19 consists of general religious and ethical precepts for daily life for the entire community. The presentation is apodictic in form and rather complex in order.

Chapter 20 corresponds closely to Chapter 18, providing rules for sexual behavior and other general regulations. Provision is made for the death penalty.

Chapter 21 provides for the ritual purity or holiness of the priesthood. Aaron symbolizes the high priest and his sons the general priesthood.

Chapter 22, written in impersonal casuistic style, is concerned with holy things, cultic offerings and gifts.

Chapter 23 presents the festal calendar (cf. Deut. 16) covering the Sabbath, feasts of unleavened bread, Firstfruits, Pentecost, atonement and ingathering or booths.26

Chapter 24 is composite, dealing with the role of the high priest (24:1-9), and providing a legal example for the punishment of blasphemy by a foreigner (24:10-23).

Chapter 25 discusses the Sabbatical year and the year of Jubilee.

Chapter 26 consists of blessings and curses. The Holiness Code was incorporated into the Torah, but just when this was done cannot be determined. Some of the laws are not uniquely Israelite but represent the broad general basis of law in the Near East;27 others represent laws specifically designed for the Jewish community.

Babylonian Akitu Festival

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “The most important religious celebration of Babylon and one that provides a background for understanding II Isaiah was the Akitu festival1 observed annually from the first to twelfth of Nisanu (Hebrew Nisan: March-April). The festal origins may lie in Sumerian times; the rites continued to be observed into the Persian-Greek period. The chief figure in the cult during the Neo-Babylonian era was Marduk, god of Babylon and supreme deity in the empire. His temple, called Esagila ("House of the Uplifted Head"), stood near the great ziggurat. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

“Rituals of preparation occupied the first days and included lustration rites, the carving of images of wood, which were then overlaid with gold and ornamented with jewels and semi-precious stones (Isa. 40:18-20; 41:7), and prayers for blessing. The temple was ceremonially cleansed and wiped down with the body of a sacrificed sheep and with oils.

“The recitation of the Enuma Elish,2 the creation myth of Babylon, was also part of the ritual. This myth relates the story of the birth of the gods, the battle between Marduk, champion of order, and Tiamat, symbol of chaos, and the creation of man in a god-ordered universe. Opening verses describe a time when there was neither heaven nor earth but only the watery abyss ruled by Apsu, symbol of fresh water, and his consort Tiamat, the sea. Out of the first principle, water, came heavenly beings, created in pairs. With the arrival of many offspring came noise so upsetting that Apsu and Tiamat planned to kill their grandchildren. The plot, overheard by the wise earth god Ea, was foiled with the killing of Apsu. But Tiamat was still alive. Mustering her creative powers, she formed frightful monsters and over this array placed one of her children, Kingu, pinning on his breast the tablets of destiny, symbolic of control of the future. The stage was now set for a dramatic, cosmic encounter of gods.

“When none among the gods of order was able to stand up to Tiamat and Kingu, Marduk, son of Ea and his wife Damkina, entered the arena having been promised supreme kingship should he defeat the enemy. Kingu was overcome and the tablets of destiny became the property of Marduk. Tiamat was killed and split in two, like an oyster. With one half of the dead goddess, Marduk formed the arch of the heavens and with the other half, the earth. In the realm above he set Ann the sky god, in the realm below Ea, the earth god, and between the two the air god, Enlil. Other gods were given abodes in the heavens and the stars were formed in their likeness, with constellations to mark the passage of time. The sun, moon and stars were heavenly bodies with special courses to run.

“Marduk was acknowledged as king by the other gods. To serve the needs of the deities, Marduk created man, moulding the human form out of clay mingled with the blood of the dead Kingu. A shrine was built to Marduk where the gods might visit and pay homage, and his city was called Bab-ilu or Babylon, "gate of gods."

“On the days of the Akitu festival following the recitation of the Enuma Elish the king was ritually deposed, deprived of symbols of office and compelled to make a negative confession before Marduk. Subsequently he was restored to office in a ceremony in which his face was slapped until the tears ran, a symbol that Marduk was friendly. A human scapegoat, usually a condemned prisoner, was paraded through the streets.3 Scapegoat rituals are communal purgation rites in which the sins of the community are placed upon the victim. The expulsion and destruction of the scapegoat rendered the community cleansed of taint and ready to begin the new year.

“The next day the god Nabu (Nebo in Isa. 46:1) arrived from Borsippa, then, subsequently, the other gods. For a time Marduk disappeared later to reappear, suggesting some form of a death-resurrection emphasis. On the eleventh day, at the divine assembly held in the chamber of destiny, the fate of the nation for the coming year was determined, possibly by sacred oracles or by magic. To ensure fertility, a sacred marriage was performed. On the final day, at a great banquet accompanied by much sacrificing, the unity of the nation was cemented in commensality rites enjoyed by gods, king, priests and people. On this day the king took the right hand of the god, perhaps in a ritual in which the god was led to his throne but certainly as a symbol of divine favor and blessing (cf. Isa. 45:1). At the close of the ritual, the various gods returned to their own cities.

Last Days of the Neo-Babylonian Empire

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: ““Nebuchadrezzar died in 562. During his reign he maintained control of his vast empire with difficulty. A rival, King Cyaxeres of Media, began to build a powerful state with its capital at Ecbatana. Median tribes were subdued, Armenians overcome and the new Median empire pushed into Asia Minor, only to be stopped by the Lydians. During this period, Nebuchadrezzar was campaigning in the west, attempting to quiet unrest that had developed, perhaps augmented by the efforts of the Egyptian Pharaoh Apries or Hophra (589-569). After a thirteen year siege, Tyre became a Babylonian possession with semi-independence (cf. Ezek. 29:17-20). Meanwhile, Pharaoh Apries was defeated by the Greeks at Cyrene (570). In 568, perhaps to prove to the Egyptians the folly of pressing into Asia, Nebuchadrezzar invaded Egypt. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org]

fall of Babylon from the Nuremberg chronicles

“When Nebuchadrezzar died in 562, his long rule was followed by a period of social upheaval and in seven years four different monarchs sat on the Babylonian throne. Amel-Marduk (562-560), a son of Nebuchadrezzar, died a violent death and is believed to be the Evilmerodoch of II Kings 25:27-30 who released King Jehoiakim from prison. Nergal-shar-usar (cf. Jer. 39:3, 13: possibly Nergal-sharezer), a brother-in-law, ruled four years (560-556) and just prior to his death suffered defeat in a battle with the Medes. His infant son Labashimarduk was scarcely crowned when Nabonidus or Nabu-na'id, who was not of the same family, seized the throne in a rebellion supported by chief officials of state.

“Nabonidus' mother was a high-priestess of the moon god Sin and his father was a nobleman, and Nabonidus came into conflict with the priests of Marduk, perhaps through his efforts to make Sin the chief god of the empire. A famine attributed to royal impiety, together with spiraling inflation, produced tension within the empire. Nabonidus moved to the desert oasis of Teima (southeast of Edom) and from this center established military and trade posts throughout the desert as far as Yatrib (later Medina) near the Red Sea. In Babylon, his son Bel-shar-usur (Belshazzar in Daniel) ruled as regent from 552-545. The absence of the monarch created serious religious problems, particularly for the annual Akitu or New Year festival. Finally the monarch returned to Babylon, perhaps to lead his forces against Elamite raiders in southern Babylonia. But new forces were at work that were to deprive him of his crown and terminate the Neo-Babylonian empire.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons, Schnorr von Carolsfeld Bible in Bildern, 1860

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, Live Science, Archaeology magazine, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024