Home | Category: David and Solomon / Hebrews in Babylon and Persia / David and Solomon / Hebrews in Babylon and Persia

AFTER SOLOMON

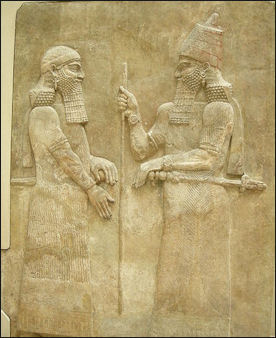

King Rehoboam consulting with the old men

After Solomon, the Hebrew kingdom was ruled his son Rehoboam, who proved to be a more brutal leader than his father. There was a revolt against the House of David around 930 B.C. and the Hebrew kingdom divided into two kingdoms: the southern kingdom of Judah in the south with Jerusalem as the capital and Rehoboam as the ruler; and another kingdom in the north with Samaria as the capital. Of the 12 Tribes of Israel, the 10 northern tribes of Israel broke off to establish the Kingdom of Israel. Rehoboam ruled over the southern Kingdom of Judah, which included only the tribes Judah and Benjamin and was relatively small in size compared to Solomon’s kingdom.

Most of the events in the Bible after Solomon are believed to be based on historical fact. There is firm historical or archaeological evidence for: 1) the conquest of Israel by the Assyrians in the 8th century B.C." 2) the conquest of Jerusalem by Babylon's Nebuchadnezzar around 600 B.C." 3) the exile of Jews to Babylon and the destruction of Solomon's temple in 587 B.C. Excavations in Iraq have turned up a list of rations given by Nebuchadnezzar to "Yaukin, king of Judah," which is believed to be a reference to the exiled Israelite king Jehoiachin whose release is recorded in 2 Kings 25.

There is firm historical evidence for: 4) the conquest of Babylonia by King Cyrus of Persia and the return of the Jews to Jerusalem in the 6th century B.C." 5) the building of the Second Temple in the 6th century B.C." 6) the rebuilding of Jerusalem's walls the 5th century B.C." 7) the annexation of Palestine by Ptolemaic Egypt in the 4th century B.C." 8) and the plunder of the Temple by the Romans the 2nd century B.C.

Websites and Resources: Virtual Jewish Library jewishvirtuallibrary.org/index ; Judaism101 jewfaq.org ; torah.org torah.org ; Chabad,org chabad.org/library/bible ; Bible and Biblical History: ; Biblical Archaeology Society biblicalarchaeology.org ; Bible History Online bible-history.com Bible Gateway and the New International Version (NIV) of The Bible biblegateway.com ; King James Version of the Bible gutenberg.org/ebooks ; Jewish History: Jewish History Timeline jewishhistory.org.il/history Jewish History Resource Center dinur.org ; Center for Jewish History cjh.org ; Jewish History.org jewishhistory.org ; Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Christianity: BBC on Christianity bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity ; Christian Classics Ethereal Library www.ccel.org ; Sacred Texts website sacred-texts.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“King Solomon's Empire: The Rise, Fall, and Modern-Day Influence of an Iron-Age Ruler”

by Archie W. N. Roy PhD and Margaret P. Roy Amazon.com ;

“The Temple of Solomon” by Kevin J. Conner Amazon.com ;

“Why the Bible Began: An Alternative History of Scripture and its Origins” by Jacob L. Wright Amazon.com ;

“The History of Saul, David and Solomon: Israel's Greatest Kings” by James Allen Moseley

Amazon.com ;

“Synchronized Chronology: for the Ancient Kingdoms of Israel, Egypt, Assyria, Tyre, and Babylon” by Dan Bruce Amazon.com ;

“Twelve Tribes of Israel” by Rose Publishing Amazon.com ;

“The Myth of the Twelve Tribes of Israel” by Andrew Tobolowsky Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jewish People During the Babylonian, Persian, and Greek Periods”by Charles Foster Kent Amazon.com ;

“The Kings and Prophets of Israel and Judah: From the Division of the Kingdom to the Babylonian Exile (Classic Reprint)” by John Foster Mitchel Amazon.com ;

“The Bible Unearthed” by I. Finkelstein and N. Asher Silberman Amazon.com ;

“NIV, Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible (Context Changes Everything) by Zondervan, Craig S. Keener Amazon.com ;

“Oxford Companion to the Bible” by Bruce M. Metzger and Michael David Coogan Amazon.com ;

“Historical Atlas of the Holy Lands” by K. Farrington Amazon.com ;

“The Story of the Jews” Volume One: Finding the Words 1000 BC-1492 AD by Simon Schama (Author) Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jews” by Paul Johnson, Amazon.com

Divisions Within the Hebrew Kingdoms

Jewish history was shaped almost as much by internal rivalries as it was by threats from the outside. Gopnik wrote in The New Yorker: The southern Kingdom of Judah and the northern Kingdom of Israel, which we might have imagined as agreeable sister kingdoms, were, in the centuries around 900-700 B.C., warring adversaries, though a single deity, one of many names, was shared between them. The oldest deity, El — “Israel” is usually interpreted to mean “One who struggles with God” — got replaced over time by the unnameable deity Yahweh, who originally had a female companion, and then by a more metaphysical maker, Elohim. [Source: Adam Gopnik, The New Yorker, August 21, 2023; Book: “Why the Bible Began,” by Jacob L. Wright]

In his book “Why the Bible Began,” the scholar Jacob L. Wright traces the narrative rivalries and divisions that formed the Hebrew Scriptures. Wright stresses the extent of the disruption that occurred when Israel was subjugated by the Assyrians while Judah maintained self-rule for more than a century afterward. (A blink in Biblical time, perhaps, but it’s an interval like the one that separates us from the Civil War.) It was during this period, he argues persuasively, that a fundamental break happened, leaving a contrapuntal discord in the Bible between the southern “Palace History” and the “People’s History” of the dispossessed northern scribes. The Palace History conjured up Saul and David and Solomon and the rest, still comfortably situated within a “statist,” dynastic Levantine court; the People’s History, by contrast, was aggressively indifferent to monarchs, real or imagined, and concentrated instead on popular figures, Moses and Miriam, the patriarchs and the prophets. The Jewish tradition of celebrating non-dynastic figures of moral or charismatic force — a practice mostly unknown, it would seem, in the rest of the ancient world — begins in the intersection of dispossessed Israelites and complacent Judaeans.

The northern and the southern narratives were, Wright says, constantly being entangled and reëntangled by the Biblical writers, as a kind of competition in interpolation. So, for instance, Aaron the priest is interpolated latterly as Moses’ brother in order to align the priestly court-bound southern caste with the charismatic northern one. Again and again, what seems like uniform storytelling is revealed to be an assemblage of fragments, born from defeat and midwifed by division.

Timeline of Judah

ca. 931 B.C.: Secession of Northern Kingdom (Israel) from Southern Kingdom (Judah)

931-913 B.C.: Rehoboam rules Judah

931-910 B.C.: Jeroboam I rules Israel, choses Shechem as his first capital, later moves it to Tirzah

913-911 B.C.: Abijah rules Judah

911-870 B.C.: Asa rules Juda

910-909 B.C.: Nadab (son of Jeroboam) rules Israel

909-886 B.C.: Baasha kills Nadab and rules Israel

Nadab

900-612 B.C.: Neo-Assyrian period

886-885 B.C.: Elah, son of Baasha, rules Israel

885 B.C.: Zimri kills Elah, but reigns just seven days before committing suicide, Omri chosen as King of Israel

885-880 (?) B.C.: War between Omri and Tibni

885-874 B.C.: Omri kills Tibni, rules Israel

879 B.C.: Omri moves capital of Israel from Tirzah to Samaria

874-853 B.C.: Ahab, Omri's son, is killed in battle, Jezebel reigns as Queen. Athaliah, Ahab and Jezebel's daughter, marries Jehoram, crown prince of Judah

870-848 B.C.: Jehoshapha rules Judah

853-851 B.C.: Ahaziah, son of Ahab, rules Israel, dies in accident

750-725 B.C.: Israelite Prophets Amos, Hosea, Isaiah [Source: Jewish Virtual Library, UC Davis, Fordham University]

722/721 B.C.: Northern Kingdom (Israel) destroyed by Assyrians; 10 tribes exiled (10 lost tribes)

720 B.C.: Ahaz, King of Judah dismantles Solomon's bronze vessels and places a private Syrian altar in the Temple

716 B.C.: Hezekiah, King of Jerusalem, with help of God and the prophet Isaiah resists Assyrian attempt to capture Jerusalem (2 Chronicles 32). Wells and springs leading to the city are stopped

701 B.C.: Assyrian ruler Sennacherib beseiges Jerusalem

612-538 B.C.: Neo-Babylonian (“Chaldean”) period

620 B.C.: Josiah (Judean King) and “Deuteronomic Reforms”

ca. 600-580 B.C.: Judean Prophets Jeremiah and Ezekiel

In 2015, Israeli archeologists announced they had discovered a mark from a seal of the biblical King Hezekiah. The discovery was touted by some as proof of the authenticity of the biblical record. According to the Daily Beast The small circular inscription was found as part of excavations of a refuse dump at the foot of the southern wall that surrounds Jerusalem’s Old City. The clay imprint, known to archeologists as a bulla, contains ancient Hebrew script and a symbol of a two-winged sun. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, December 3, 2015]

Age of Prophets

After the Jewish kingdom fell apart around 920 B.C. it was the time of the prophets. According to Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: In the eighth century B.C. the prophet Amos, who came from the Kingdom of Judah, fulminated against the oppression of the poor and disinherited members of society. Because of divine election, Amos taught, the Children of Israel, in both the north and the south, had a responsibility to pursue social justice. In contrast to Amos, who stressed justice, the contemporary prophet Hosea spoke of loving kindness. God loved his people, but they did not requite his love and "whored" with Baal, the pagan god of the Phoenicians. In a dream God commanded Hosea to marry a harlot to symbolize Israel's immoral behavior, while at the same time highlighting God's forgiveness and abiding love.

Active during the reign of four kings of Judah, the prophet Isaiah (8th century B.C.) castigated the monarchs for forging alliances with foreign powers, arguing that the Jews should place their trust in God alone. Isaiah lent support to King Hezekiah (727-698 B.C.), who instituted comprehensive religious reforms by uprooting all traces of pagan worship.

The prophet Jeremiah (7th- 6th centuries B.C.) denounced what he regarded as the rampant hypocrisy and conceit of the leadership of Judah. When the Babylonians reached the gates of Jerusalem, Jeremiah claimed that it would be futile to resist, and, accordingly, he urged the king to surrender and thus spare the city and its inhabitants from further suffering. His prophecy of doom earned for him the scorn of the leadership and masses alike. When the city fell in 597, he was not exiled to Babylonia with the rest of the political and spiritual elite. He eventually fled to Egypt, where he was last heard of fulminating against the idolatry of the Jews there.

The Kingdom of Israel came to an end in 722 when it was conquered by the Assyrians, who exiled the inhabitants. These 10 tribes of Israel were henceforth "lost" from history. [Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s Encyclopedia.com]

Discord in Judah After Solomon

For 200 years the northern and southern kingdoms fought one another. Samaria was fertile and rich and its people prospered as farmers and traders while Judah was rocky and deserty, and it people remained herders. The prophets Amos, Hosea and Isaiah warned about the growth of idolatry and divisions between rich and poor. God seemed to favor the southern kingdom. Zachariah 14:12 reads: “As for those peoples that warred against Jerusalem their flesh shall rot away while they stand on their feet."

Baasha'

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “The record of Solomon's greatness fails to indicate the seething bitterness and resentment that must have been developing among the people. Only when Rehoboam appeared for succession rites were the feelings expressed by those who bore with smoldering anger the heavy burdens of Solomon's despotism. The northern and southern peoples were kept from full union by geographical factors, by the northern people's basic distrust of the Davidic monarchy with its center in Jerusalem (a southern city despite its proximity to the north-south border), by resentment to Solomon's extravagant excesses and the resultant heavy taxation, and possibly even by different religious or theological outlooks indicated by the support of the schism by the prophet Ahijah (I Kings 11:29 and following verses). [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org]

Judah appears to have accepted Rehoboam without question, but when the young prince went to Shechem to be anointed king and received the approbation of the people, he was confronted with a demand for a policy statement. The request reveals the severity of Solomon's rule: “Your father made our yoke heavy. Now therefore lighten the hard service of your father and his heavy yoke and we will serve you. (12:4)

Rehoboam turned to his advisors for counsel: the elder statesmen recommended compliance while the younger men advocated a "get-tough" policy. Rehoboam accepted the latter. His arrogant and harsh rejection provoked immediate response: withdrawal from the United Kingdom. The rebel cry was an old one (cf. II Sam. 20:1):“What portion have we in David? We have no inheritance in the son of Jesse. To your tents, 0 Israel! Look now to your own house David. (12:16) Jeroboam, the exiled taskmaster who had recently returned from Egypt, became the first king of Israel. Rehoboam ruled Judah. Gone forever was the United Kingdom; and in the eighth century Israel disappeared altogether from history.”

Biblical Accounts of Post-Solomon Judah

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “Against this background of Near Eastern history the internal history of the Hebrew kingdoms must be studied. For this history we are dependent upon accounts in Kings and Chronicles and limited information coming from archaeological research. The Deuteronomic editors of Kings may have drawn upon official court records, but their work betrays theological and Judaean bias.

Each monarch is judged on the basis of his adherence to the principles of southern Yahwism and his opposition to Ba'alism and other religions. Consequently no Israelite king is commended and only two Judaeans, Hezekiah and Josiah, are fully approved, although six others receive modified approbation. When the editorial evaluation is removed, there remains an outline of successive rulers with brief comments on significant events of their reigns. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

“Writing in the fourth century, the Chroniclers utilized an edition of Kings similar to the one we possess but did not hesitate to supplement the narratives. Some additions appear to have historical validity; others reflect theological convictions. Historical data in Kings and Chronicles must be accepted cautiously, and most additional material in Chronicles remains sub judice, except where sustained by archaeological or other confirming evidence.

Fighting and Rivalry with Judah

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “Rehoboam (922*) , son of Solomon, having lost Israel, Ammon and Moab, was determined to regain these territories. Dissuaded by Shemaiah's prophetic warnings, he strengthened Judaean fortifications, but his efforts failed to prevent invasion by Sheshonk of Egypt. Judaean villages were destroyed, Jerusalem entered, and the Temple plundered. The raid must have affected Judaean military strength adversely, and the intermittent warfare with Israel attempting to fix the Israel-Judah border continued to drain the national resources. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org]

Omri

“Abijah (915) or Abijam, Rehoboam's son and successor, may have pushed Judaean borders as far north as Bethel (II Chron. 13), but he was unable to retain control of this important Israelite city. (913) Asa, the next king, is commended by the editors for his efforts to subdue the fertility cults. During his reign, border warfare with Israel continued. When Baasha began to build Ramah to sever Judah's northern trade route, Asa bribed Ben Hadad of Syria to move the Syrian armies to Israel's northern frontier. Baasha's men withdrew from Ramah and Asa stole the building materials and constructed fortresses at Mizpah (possibly Tell en-Nasbeh) and Gibeah just north of Jerusalem. The Chroniclers record a battle between Judah and the Cushites or Ethiopians (II Chron. 14:9 ff.) but this has not been verified.

“It was not until Jehoshaphat (873), Asa's son, became king that peace was established between the two Hebrew kingdoms and cooperative attacks on mutual enemies were undertaken. Jehoshaphat's son, Jehoram, married Athaliah, daughter of Ahab of Israel (II Kings 8:26), thus linking the Divided Kingdom through royal marriage. The Judaeans joined the Israelites in the Syrian-Israelite war (I Kings 22:2f.) and later, when the Moabites rebelled, southern soldiers assisted Israel (II Kings 3:7 ff.). Jehoshaphat was succeeded by his son Jehoram (849), son-in-law of Ahab, and during his reign Edom broke free of Judaean control (II Kings 8:20-22).

“When Jehoram's son Ahaziah (842) (Read II Kings 9-10), king of Judah, was killed by Jehu of Israel, his mother Athaliah (842) (Read II Kings 11) ascended the throne to become the first and only Hebrew woman to reign. Eligible heirs, with the exception of Joash or Jehoash, the infant son of Ahaziah, were murdered. Joash was concealed in the temple by his aunt, the wife of the chief priest (II Chron. 22:11). Athaliah was not tolerated for long. She was an usurper, standing outside of the Davidic line, and she encouraged Baalism. Joash (837) (Read II Kings 12-13) was seven years old when he was crowned king in a secret ceremony and, in the uprising that followed, Athaliah was murdered. As Jehu persecuted Baal worshippers in Israel, Joash attacked them in Judah. Joash was murdered by his servants and his son, Amaziah (800) (Read II Kings 14), ascended the throne. Territory lost to Edom was repossessed and the Edomite mountain fortress of Sela (Petra) invaded. In war with Israel Amaziah was defeated and Jehoash's army looted the holy temple. Like his father before him, Amaziah died at the hands of his servants. Azariah or Uzziah (783), son of Amaziah, fought the Edomites when he came to the throne and Judah gained control of the important Red Sea port of Elath (Ezion-geber). Unfortunately, Azariah contracted leprosy (attributed by the Chroniclers to a cultic violation) and was compelled to live in isolation, and his son Jotham governed as regent (cf. II Kings 15:1-7; II Chron. 26). In the year that Azariah died the prophet Isaiah began his work.

“Jotham (742) was regent for eight years before gaining the crown. Little is known of his reign except that the Temple was repaired (II Kings 15:33ff.) and, according to the Chronicler, war was waged with Ammon (II Chron. 27:5ff.). Ahaz (735), son of Jotham, refused to join an anti-Assyria coalition and, in the so-called Syro-Ephraimitic war, Judah was attacked by King Rezin of Syria and King Pekah of Israel. About the same time Edomites and Philistines united against Judah (II Chron. 28:1-21). The pressure was too much and Ahaz called on Tiglath Pileser for help. Judah paid huge indemnities for this aid and Assyrian deities were introduced into the temple of Yahweh. During this period, Edom recaptured the seaport of Elath. Ahaz' international policies were vigorously opposed by the prophet Isaiah, but there can be little doubt that Ahaz' refusal to participate in the anti-Assyria pact and his voluntary surrender of sovereignty saved Judah from Israel's fate (II Kings 16:7ff.). Judah became a vassal to Assyria, the mightiest empire the Near Eastern world had known.

Ahab

Jeroboam (922*) had won a kingdom without headquarters or government. His immediate task was the development of administrative patterns. Shechem became the capital and was fortified. To offset the attraction of the Jerusalem temple, royal sanctuaries were dedicated in the border cities of Dan and Bethel. Within these shrines golden calves, symbols of Yahweh, or perhaps pedestals upon which the invisible deity stood, were placed, and festal observances paralleling those of Jerusalem were instituted. Chapters 13-14 of I Kings which condemn Jeroboam are largely homiletic. Chapter 13, a legend about an unknown prophet, comes from the post-Josiah period (cf. 13:2). The story of the illness of Jeroboam's son may have an historical core (I Kings 14:16, 12, 17) that was expanded by later writers. What result the Sheshonk invasion had is not known, but the economy must have suffered.

“ (901) Nadab, Jeroboam's son who reigned less than two years, was murdered with all members of Jeroboam's family by Baasha (900) of the house of Issachar. Baasha fought with the Philistines, moved the capital from Shechem to Tirzah and attempted to curtail Judah's trade by building a fort at Ramah. Asa's strategy (bribing the Syrians to attack on the north) compelled Baasha to abandon his building project and move his men to deal with the Syrians. Elah (877) (Read I Kings 16), Baasha's son and successor, and all members of Baasha's family were murdered by Zimri (876), a chariot commander who had the support of the prophet Jehu. Seven days later Israelite soldiers battling the Philistines elected their field commander Omri (876*) to the kingship. Omri swiftly moved the army to Tirzah, and Zimri, doomed without military support, committed suicide by firing the royal citadel. Another contender for the throne, a certain Tibni, was eliminated. Omri purchased the hill of Samaria and constructed a new capital city. Although Omri's dynasty is dismissed in a few words by the Deuteronomic editors, perhaps because he was not a Hebrew, his family ruled for three generations and long after the dynasty had ceased Assyrian annalists referred to Israel as "the house of Omri."

The Moabite Stone records that Omri expanded Israel's borders to include northern Moab. Omri's son Ahab (869), who married Jezebel, a Tyrian princess, receives much more attention for Jezebel brought to Israel the worship of the Tyrian Ba'al, Melkart. Under royal sponsorship the cult flourished, coming into dramatic conflict with Yahwism championed by the prophetic school of Elijah. (Read I Kings 20) War flared between Israel and Syria and, after the defeat of Ben Hadad, Ahab entered into trade agreements with his former enemies and participated in a coalition with Syria and other small nations to halt the westward development of Assyria. According to the records of Shalmaneser V, Ahab contributed 2,000 chariots and 10,000 soldiers. The Assyrians claimed victory at Qarqar. Because the Israelite town of Ramoth-gilead had not been included in the peace settlement of the Syrian-Israelite war, Ahab began a new anti-Syrian campaign with the assistance of Jehoshaphat of Judah (Read I Kings 22).

Divided kingdom in 830 BC

Ahab died in battle and Ahaziah (850) (Read II Kings 1), his son, became king. Injuries suffered in a fall rendered the king powerless to control a revolt by the Moabites; after his death, his brother, Jehoram (849) (Read II Kings 3, 8), continued the war with Moab. Aided by Jehoshaphat of Judah and the Edomites, Jehoram was at first victorious, but Mesha of Moab turned the tide of battle and Moab became an independent kingdom (cf. II Kings 3 and The Moabite Stone). Elijah, the prophet, died during this period and Elisha, his disciple, became "father" or "chief" of the prophetic guild. While Jehoram and Ahaziah of Judah were engaged in battle with the Syrians, Elisha anointed Jehu (842*) king of Israel, thus engendering civil war. Ahaziah of Judah and Jehoram of Israel were killed at Jezreel, and a reign of terror began in which the family of Ahab, including Jezebel, was eliminated and the followers of Ba'al persecuted. Weakened by internal intrigue, Israel was helpless before the power of the Aramaean Kingdom of Hazael, and large amounts of territory were lost in the Transjordan area.

“Jehoahaz (815), son of Jehu, inherited a nation reduced to impotency by the Aramaeans. Jehoash (801), his son and successor, a more successful warrior, was able to recapture some of the lost land, for King Adadnirari III of Assyria broke the power of Damascus in 800. Jehoash attacked Judah, invaded Jerusalem and looted the temple. During this period Elisha, who appears to have been a friend of the king, died (II Kings 13:14ff.).

“Jeroboam II (786) (Read II Kings 15), son of Jehoash, was perhaps the most successful warrior king since David, for under his rule Israel gained mastery over Syria and Moab to control an area approximating that embraced at the time of the Davidic empire (minus, of course, Judah, Edom and Philistia). Fortunately, Jeroboam was not troubled by the Assyrians and his reign, marked by prosperity and wealth, provides a social background against which some of the prophetic utterances of Amos and Hosea must be understood. Zechariah (746), son of Jeroboam, reigned less than one year and was murdered by Shallum (745), who was promptly killed by Menahem (745). To prevent conquest by Assyria, Menahem voluntarily submitted to Tiglath Pileser III (Pul) and paid heavy tribute, a detail confirmed in an Assyrian text. Shortly after Pekahiah (738), son of Menahem, became king, he was murdered by his captain, Pekah (737) (Read II Kings 16-17). At this time participation in a political alliance against Assyria cost Israel the loss of towns in northern Galilee and Gilead. Pekah's murderer and successor Hoshea (732) seized the moment of the death of Tiglath Pileser III and the ascension of Shalmaneser V to the Assyrian throne as the time to throw off the Assyrian yoke. Counting on help from Egypt, Hoshea refused to pay tribute to Assyria. Shalmaneser attacked Samaria but died while the siege was still in process, leaving the subjugation of Israel to his successor, Sargon II (722) . When Samaria fell in 721 and all Israel capitulated, great numbers of the people (according to Sargon, 27,290) were deported to the Assyrian province of Guzanu and to the region south of Lake Urmia. From other parts of the farflung Assyrian empire, emigrants were brought to Israel. Israel's history as an independent nation had terminated. Sargon divided the territory into small provinces. Revolts were abortive. Among those Israelites who remained in the land, the worship of Yahweh continued, but homage was paid to the gods of Assyria.

Assyrian Attack on Jerusalem

Sargon II The revived Assyrian empire, conquered Israel’s northern empire in 722 B.C. After the prophet Hosea predicted that "The calf of Samaria shall be broken into pieces; for they have sown the wind, and the shall reap the whirlwind," the Assyrian king Tiglath-pilese III sacked Damascus and invaded northern Israel. In 722 B.C. northern Israel was conquered by Tiglath-pilese III's successor Shalmanseser V. Sargon recorded: "The city of Samaria I besieged. I took. I carried away 27,290 of the people that dwelt therein."

Sennacherib (705 to 681 B.C.), the Assyrian ruler of Ninevah, launched an unsuccessful siege of Jerusalem in 701 B.C. The siege was cut short, according to the Bible, by intervention by angels. An inscription on a statue found in the doorway of Sennacherib’s throne room recounts a story of bribery from the Bible, the first known independent written account corresponding to a story in the Bible.

According to Assyrian empire records, Israel was a powerful kingdom that posed a threat to Assyrian control of the region. One inscription described an army by Ahab, the husband of biblical Jezebel, as possessing 2,000 chariots, a formidable number at that time. When Israel was conquered by the Assyrians, Israelite chariot units were incorporated into the Assyrian army.

In accord with Assyrian policy of deporting the local population to prevent rebellions, the 200,000 Jews living in the northern kingdom of Israel were exiled. After that nothing was heard from them again. The only clues in the Bible were from II Kings 17:6: "...the king of Assyria took Samaria, and carried Israel away to Assyria, and placed them in Halah and in Habor by the river Gozan, and in the cities of the Medes." This puts them in northern Mesopotamia.

See Separate Article: CONQUEST OF THE JEWISH KINGDOMS BY ASSYRIA africame.factsanddetails.com

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, Live Science, Archaeology magazine, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024