Home | Category: David and Solomon / David and Solomon

DAVID

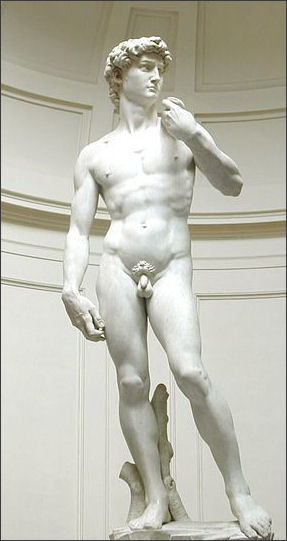

Michelangelo's David David is one the greatest figures in the Bible. The founder and king of the first and largest Jewish kingdom, he was called the “Shepherd King” because of his humble origins and Messiah (the Anointed One), a term which in his time was used to describe a high priest, but today describes a person who has been chosen by God. The rule of David and Solomon are described in the Old Testament Books: Samuel, Kings and Chronicle. David’s story in told from I Samuel 16 through I Kings 2. “David King of Israel” is a song that every Israeli school child knows.

Robert Draper wrote in National Geographic: David has persisted for three millennia — an omnipresence in art, folklore, churches, and census rolls. To Muslims, he is Daoud, the venerated emperor and servant of Allah. To Christians, he is the natural and spiritual ancestor of Jesus, who thereby inherits David's messianic mantle. To the Jews, he is the father of Israel — the shepherd king anointed by God — and they in turn are his descendants and God's Chosen People. .[Source: Robert Draper, National Geographic, December 2010]

David was anointed king in 1010 B.C. and reigned until 970 B.C.. He led the remaining forces of Israel to swift victories over the Philistines and other enemies. He then captured Jerusalem, declared it the capital of his kingdom, and had the Ark of the Covenant, containing the tablets of the Law given by God to Moses, taken there. His plan to build a great temple to house the ark was thwarted by the prophet Nathan, who claimed that God viewed David, a man of war, unsuitable for the sacred project. A warrior and statesman, regarded in Jewish tradition as the ideal ruler, David united the tribes of Israel and greatly expanded the borders of the kingdom. His reign had its share of intrigue and misfortune, still Jews believed that the Messiah, would be a descendant of the house of David (Is. 9:5-6; 11:10). [Source: Paul Mendes-Flohr Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2000s Encyclopedia.com]

Book: “King David” by Steven L. McKenzie (Oxford University Press, 2000)

Websites and Resources: Virtual Jewish Library jewishvirtuallibrary.org/index ; Judaism101 jewfaq.org ; torah.org torah.org ; Chabad,org chabad.org/library/bible ; Bible and Biblical History: ; Biblical Archaeology Society biblicalarchaeology.org ; Bible History Online bible-history.com Bible Gateway and the New International Version (NIV) of The Bible biblegateway.com ; King James Version of the Bible gutenberg.org/ebooks ; Jewish History: Jewish History Timeline jewishhistory.org.il/history Jewish History Resource Center dinur.org ; Center for Jewish History cjh.org ; Jewish History.org jewishhistory.org ; Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Christianity: BBC on Christianity bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity ; Christian Classics Ethereal Library www.ccel.org ; Sacred Texts website sacred-texts.com ;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“King David” by Steven L. McKenzie (Oxford University Press, 2000) Amazon.com ;

“The Making of a Man of God: Lessons from the Life of David”by Alan Redpath Amazon.com ;

“ David, King of Israel, and Caleb in Biblical Memory” by Jacob L. Wright Amazon.com ;

“In the Footsteps of King David: Revelations from an Ancient Biblical City” by Yosef Garfinkel, Saar Ganor, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Why the Bible Began: An Alternative History of Scripture and its Origins” by Jacob L. Wright Amazon.com ;

“The History of Saul, David and Solomon: Israel's Greatest Kings” by James Allen Moseley

Amazon.com ;

“The Bible Unearthed” by I. Finkelstein and N. Asher Silberman Amazon.com ;

“Archaeology of the Bible: The Greatest Discoveries From Genesis to the Roman Era”

by Jean-Pierre Isbouts Amazon.com ;

“Oxford Companion to the Bible” by Bruce M. Metzger and Michael David Coogan Amazon.com ;

“The Story of the Jews” Volume One: Finding the Words 1000 BC-1492 AD by Simon Schama (Author) Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jews” by Paul Johnson, Amazon.com ;

David’s Achievements

Triumph of David

David is said to have written the Psalms, unified the tribes of Israel and made Jerusalem the capital of the Israeli nation. He is considered to be Israel's greatest King, whose reign ushered in the period in which the First Temple was built. David was the first king in Jerusalem whose reign was later looked back on as a golden era. His story in full is found in the books of 1 and 2 Samuel and 1 Kings 1-2. Young David has been depicted holding a lamb in his arms with his knee on the throat of a dead lion.

Major Events and Episodes Featuring David

ca. 1010-970 B.C.: David conquers the Jebusites and makes Jerusalem his capital

David becomes king in Judah.

David unites Israel and Judah.

David conquers Jerusalem.

David brings the Ark to Jerusalem.

David extends the boundaries of the kingdom.

Absalom revolts and is killed, Adonijah revolts and is killed

Dr R. W. L. Moberly of University of Durham wrote for the BBC: “David was the first king in Jerusalem whose reign was later looked back on as a golden era. He is known both as a great fighter and as the "sweet singer of Israel", the source of poems and songs, some of which are collected in the book of Psalms. The date of David's enthronement is approximately 1000 BC. The context of his life is a time of transition within the history of Israel. Because of the lawlessness of this period there was a growing desire to have a king. A king can give strong leadership and bring victory over enemies. But a king can also cream off his people's wealth and resources to promote his own power. [Source: Dr R. W. L. Moberly, University of Durham, [Source: BBC June 25, 2009 |::|]

“The scene is set when Saul, Israel's first king, is rejected by God for disobedience. God sends the prophet Samuel to the house of Jesse to anoint a successor at God's direction. When David his youngest son appears, God tells Samuel to anoint him. David's qualities "after the Lord's own heart" are perhaps best displayed in the famous contest with Goliath. The people of Israel are confronted by their enemies, the Philistines, and are terrified of their champion, Goliath. Goliath is huge and carries overwhelming military technology. He is the ancient equivalent of the Terminator and calls for a single combat to decide the battle. |::|

David Takes Over Power from Saul

Death of Saul

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “The way was open for David to assume the throne: Jonathan, the natural successor, was dead; David had won recognition as a popular hero and a military expert, and had gained the loyalty of the southern cities of the Hebrew nation by sharing booty with them. His marriage to Michal, Saul's daughter, might also have been significant for it related David to the royal household.

“David's first move was to Hebron where he was anointed king over "the house of Judah" (II Sam. 2:2 f.). The groups forming "the house" are not indicated, but Martin Noth has suggested that a six-tribe confederation consisting of Judah, Caleb, Othniel, Cain, Jerahmeel and Simeon might have been involved. Apparently the Philistines were unconcerned, for they counted David as an ally. David now began to woo the northern groups. A letter to Jabesh-Gilead commended the people for providing proper burial for Saul and Jonathan, offered David's support and reminded them that David was now king (II Sam. 2:5-7).

“But the northern tribes had taken other action. Abner, Saul's commander-in-chief, had Saul's fourth son, Ishbaal, appointed king in Israel. No mention of Ishbaal has been made prior to this time, and nothing is known of him apart from a note appended by a Deuteronomic redactor to the effect that he was forty years old at this time (II Sam. 2:10-11).

“A curious episode interrupts the narrative to explain the hostility between Abner, commander of the army of Ishbaal, and Joab, commander of David's forces. Twelve men from each of the armies engaged in a contest in which combatants paired off, each placed one hand upon the head of the adversary and with the free hand sought to thrust him through with a sword. The significance of this strange match is not known, although a relief from Tel Halaf depicts men in this very position. Abner's men were defeated and Abner and those who remained fled. In the pursuit, Asahel, a brother of Joab, followed Abner and was killed by the more experienced warrior. The battle marked the beginning of a protracted struggle between Ishbaal and David in which "David grew stronger and stronger, while the house of Saul became weaker and weaker" (II Sam. 3:1). Later, a literal-minded editor inserted an isolated fragment about David's family, portraying David's growth in strength in terms of his six wives and six sons (II Sam. 3:2-3).

“Now problems developed within Ishbaal's household. Abner took one of Saul's concubines for himself and inasmuch as the taking of a king's widow could be construed as seeking to take the place of the dead king, Ishbaal questioned Abner's intentions. Angered by the accusation (which may have been justified), Abner offered to bring Israel under David's control if David would enter into a covenant with him. What Abner was to gain is not stated, unless it would be a guarantee of safety and security and position with David. David accepted but demanded the return of his wife Michal, Saul's daughter. Once this action, a token of good intention, had been taken, Abner began to undermine Ishbaal's position among the northern tribesmen. Subsequently twenty northern leaders and Abner participated in a feast as David's guests to plan strategy for bringing Israel under Davidic rule.

“But David had failed to consider Joab. As redeemer-of-blood7 for the death of his brother, he killed Abner, placing David in the embarrassing position of having to retain his friendship with Joab and hold the loyalty of the northern tribesmen with whom he had broken bread. The compromise was effected by David's denial of any part in Abner's death, by his public lamentation in which he composed a dirge for Abner, and by the participation of Joab in the mourning rites. The dirge (II Sam. 3:31-34), like that for Saul and Jonathan, may be a Davidic composition.

“The report of Abner's death in the northern kingdom was accepted as a sign of impending doom. Ishbaal was murdered by two military leaders who removed his head and brought it to David, seeking his favor (II Sam. 4:4-11). Although he had gained politically through this event, David could not afford to express approval. The two were promptly executed (II Sam. 4:12).”

David Becomes King

David became king of the Jews after Saul was killed by Philistines in a battle on Mount Golbia after he lost favor with God. The Philistines were helped by the fact that David had a formidable army in southern Israel and Saul had to be prepared for a fight on two fronts.

David was anointed the king in the southern city of Hebron. David had a covenant with God that stated that David's Jewish nation would never be conquered. This mirrored what God had earlier told Moses: "ye shall rule over many nations but they shall not rule over thee.” David ruled the Israelites from Hebron before he made is move on Jerusalem.

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “All opposition was now removed and David entered into a covenant with the northern tribes and was anointed king at Hebron (II Sam. 5:1-3). His role as "shepherd" of Yahweh's people was carefully delineated, and it is possible that the covenant took the form of a written contract agreed to by both parties, sworn to before Yahweh, and deposited in the Hebron sanctuary. Through this event the tribes of the north and of the south, first brought together through a national emergency under Saul, accepted the concept of nationhood. Undoubtedly the nation was weak and, without continuing crises, could easily have disintegrated through national suspicions and jealousies. Apparently David recognized the uneasy nature of the bond and took steps to consolidate the kingdom. The neutral Jebusite city of Jerusalem, which had remained free of Hebraic control up to that time, was taken, and this strong fortified hill-city strategically located near the border between the north and south, became the capital. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

“At this point a number of isolated fragments have been inserted into the narrative. At II Sam. 5:4-5 a Deuteronomic editor added a note about David's age and the time spent in Hebron. Another insertion at 5:8b relates how a proverb came into being. In 5:11-12 a brief statement about David's palace appears, and verses 13-14 give details about his expanding harem as David cemented good relationships with the Jebusites by marrying some of the townswomen.

“Philistine reaction to David's assumption of the combined thrones of Israel and Judah was not delayed, for verse 17 records that the Philistines attacked upon hearing the report of the anointing at Hebron. David met and defeated his former allies in the valley of Rephaim, west of Jerusalem. Other battles with the Philistines are reported (cf. 18:1), but it would seem that from this time on they posed no real threat to the Davidic empire.

“Having achieved political union and having made Jerusalem the capital, David now sought to make this city the center for the national cult of Yahweh. The sacred ark was brought into the city with great rejoicing (ch. 6). The reference in 6:19 to raisin cakes, usually associated with the worship of foreign deities or with the fertility cult,9 may indicate an adoption of features of Canaanite religious practice by the Yahweh cult. Ritual sacrifices associated with the moving of the ark were performed by David. No special shrine or temple was constructed for the ark, making it necessary for a writer to explain why David failed to build a temple for Yahweh although he constructed a palace for himself (ch. 7).

“Two isolated fragments of Davidic history comprise Chapter 8. The first summarizes David's military campaigns (8:2-14): he subdues Moabites, Edomites and Ammonites, making these areas subject states controlled by garrisons. Despite the absence of references to the conquest of other Canaanite city-states such as Jerusalem, it can be safely assumed that they were brought under control, for it is quite clear that David intended to develop a kingdom free of conflicting elements. The second historical note lists the officials of David's court (8:15-18). Joab was commander-in-chief of the army, but a certain Benaiah is said to have been in charge of the mercenaries made up of Cretans (Cherethites) and Philistines (Pelethites). In addition to a court recorder and a secretary, two priests are named, and David's sons are also said to be priests. A similar list of officials is given in II Sam. 20:23-26 with the role of chief of forced labor added, implying that David initiated the corvée. Such lists demonstrate that the old "chieftain-type" kingship represented by Saul belonged to the past; kingship now involved administration of a large unified central state and military control of subject areas. Gone forever was the time when it could be said "everyone did what was right in his own sight."

“Quite suddenly, the early narrative introduces Saul's grandson Meribaal (ch. 9), and here it is best to follow the suggestion made by a number of scholars and insert II Sam. 21:1-14 into the text before the discussion of Chapter 9. Not only do these verses provide a setting for the discussion in Chapter 9, but in their present position they stand as an isolated fragment.10

Trials for David as Ruler of Hebron

Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “A famine in David's kingdom was attributed to the death of the Gibeonites at the hand of Saul (II Sam. 2 1:1).11 There is no record of Saul's action and precisely what crime is referred to is not clear. Perhaps it was thought that the killing of the Gibeonites was a violation of the covenant of peace recorded in Joshua (ch. 9), for the writer takes pains to point out that the Gibeonites were not Hebrews. It is also pointed out that Saul acted out of zeal for the kingdom. In view of these statements, it would appear that the writer is attempting to demonstrate that David's subsequent actions were more a matter of political expediency than anything else, for David agreed to atone for the death of the Gibeonites by giving seven of Saul's sons, any one of whom might have been considered a contender for the throne, to the Gibeonites for hanging. On the other hand, the Semitic belief that physical disasters, such as famine, could be accounted for by acts which offended the deity might have been involved. In this instance the violation of a covenant of peace could be interpreted as the cause of a famine that would continue until the breach was rectified. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

“The mountain of Yahweh where the men were hanged was probably the high place of Gibeon, a Canaanite shrine used for Yahweh worship. Saul's concubine, Rizpah, protected the bodies from attacks by carrion birds. The bones of Saul and Jonathan were eventually exhumed and, together with the remains of the seven sons, were interred in the tomb of the family of Kish.

Rembrandt's The Toilet of Bathseba “One descendant of Saul, Meribaal, the son of Jonathan, was spared, perhaps because of the friendship which had existed between David and Jonathan, but perhaps also because as a cripple or deformed person he could not be considered a rival for the throne. It is possible that David hoped to win support from those who still believed in the Saulite kingship and resented the assumption of the throne by David. Thus, Meribaal entered David's household.

“Chapter 10 of II Samuel makes it clear that David did not hold his newly conquered territories without effort. The death of a king who had signed a treaty with David brought to the throne a successor who resented Hebrew control and who planned rebellion. Thanks to the military skill of Joab, the Hebrews defeated the rebels. Suddenly the story of the rebellion is interrupted, and the reader is informed of what was taking place at the court at this same time. The account of the armies in the field is taken up again in chapter 12:26-31.

David and Bathsheba

David seduced Bathsheba, wife of Uriah the Hittite, who was then killed after being sent to the front line of battle by David. The Prophet Nathan predicted that tragedies would occur in David’s family for this evil deed. Bathsheba later gave birth to Solomon.

Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “From what may be personal records or personal knowledge of the court life of David, the writer of the early materials provides a glimpse into family relationships in the royal household. Whatever prowess David may have shown as a military leader was utterly lacking in his leadership within his family. His own ruthlessness, in taking whatever he desired, is partially revealed in the story of the acquisition of the kingship, and is fully portrayed in the story of Bathsheba. What David was in himself was reflected in the character of his family. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

“The Bathsheba story is told simply, without theological interpretation. As king, David had Bathsheba brought into his harem while her husband Uriah, a Hittite mercenary, was fighting in David's army. When she became pregnant David had Uriah returned home in the hope that he would spend at least one night with Bathsheba so that he could be said to be father of the child. Uriah did not go to his home. As a soldier he observed the taboo that required sexual abstinence.12 David managed to get him drunk in the hope that Uriah might stagger home, but the soldier did not break the taboo. It was clear that Uriah must die, and Uriah carried his own death warrant back to Joab, who could be trusted to do whatever David requested. Uriah was sent to one of the more dangerous battle areas and, at a crucial moment, Joab withdrew support so that Bathsheba's husband and those with him perished.

“At this point theological judgment is introduced with the appearance of the prophet Nathan (II Sam. 11:27b-12:1). The king's role as guardian of the national safety and of individual freedom is reflected in the parable Nathan related to David. A powerful, rich man fulfilled the nomadic rule of hospitality by offering the very best of provender to a guest, not by drawing from his own flocks but by stealing a lamb from a poor and weaker neighbor. In righteous anger David demanded the name of the rich man, declaring that such an act was worthy of the death penalty (12:5). Nathan's response was "You are the man" (vss. 9b to 12 are a later addition). While David was not to suffer the penalty he had pronounced, the child of the unlawful relationship with Bathsheba was to die. David's reaction to the pronouncement of doom for his child reflects his pragmatic approach to religion. While the child lived David fasted hoping that Yahweh would be persuaded to alter the child's fortune. When the child died, rather than performing the customary mourning rites David returned to the normal pattern of life (12:20-23). A footnote to the story announces the birth of Solomon and the pet name given by Nathan to the new prince - Jedidiah or "Beloved of Yahweh" (12:24 f.)

David and Absalom

David mourns the death of Absalom

David had many wives and many children. The most well known of his sons was Absalom who was forced to flee David’s court after he killed his half-brother Ammon in revenge for raping their sister Tamar. Absalom later died in a battle against his father after his hair became entangled in a tree and he was dispatched by one of David’s generals.

The rape of Tamar and the death of Absalom were regarded as fulfillments of Nathan’s prophecy. David was devastated by Absalom’s death. According to 2 Samuel 18:33, he cried: “Oh my son Absalom! Would I had died instead of you. Oh Absalom, my son, my son!”

Larue wrote: “Subsequent chapters recount the decaying family relationships within David's household. Amnon, one of David's sons, raped his half-sister Tamar and was killed by Tamar's brother, Absalom. To escape punishment Absalom fled and David, while mourning for Amnon, longed to see Absalom (13:37-39). Joab knew David's mind and arranged for a "wise woman," possibly a representative of the wisdom school, to present a problem to the king. Once again the accessibility of David to the common people demonstrates the role of the king as defender of human rights. Like Nathan, the woman posed a problem involving Semitic justice, and once again David in his response judged himself. David recognized Joab's role in this plot and sent Joab to bring Absalom back from exile. Two years later Absalom was fully readmitted to the royal household (ch. 14). [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

“Absalom began to undermine David by suggesting that David was neglecting his duty of safeguarding the rights of his subjects. Within four years he had won enough people to his way of thinking, including David's counselor, Ahithophel, that he dared to be crowned king at the shrine in Hebron (15:1-12). David fled, leaving ten concubines to care for the palace, Zadok and Abiathar to care for the ark, and Hushai to act as spy.

“The problems of that hectic period were further complicated by Meribaal, son of Jonathan, who thought that the state of disorder provided opportunity for seizure of the throne (16:1-14). The attitude of Shimei makes it clear that then was a faction still loyal to Saul that Meribaal might count upon for support. Meribaal's plans never developed; Absalom took over the palace and erected his personal tent upon the roof, proclaiming to all that he had usurped his father's throne and was master of the royal concubines. The taking of the royal concubines constituted a proclamation of kingship, and there is some evidence in the Bible that a new king inherited his predecessor's harem.13 Then Absalom made the error that cost him the kingdom. Relying upon the advice of David's spy, Hushai, and rejecting the counsel of Ahithophel, he failed to press his advantage by attacking David when the royal forces were still unorganized (ch. 17). Meanwhile David mustered his army and Absalom was defeated and killed in the battle of the forest of Ephraim (ch. 18). David's mourning for Absalom was so intense that Joab warned the king that he was making a bad impression upon those who had fought to retain his kingdom and that military victory was a time for rejoicing (19:1-15). In a spirit of magnanimity David forgave those who had opposed him, including Meribaal, and rewarded the faithful with the exception of Joab who had rebuked him. Joab was replaced as commander by Amasa. The spirit of distrust between north and south was not diminished and the sense of being separate peoples was still prevalent (cf. 19:41-43).

David's Conquest of Jerusalem

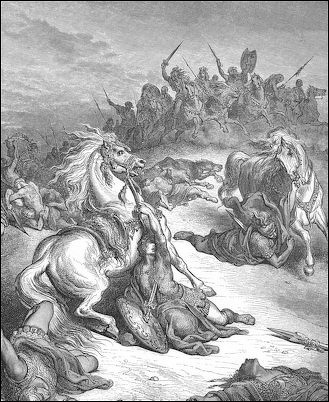

Combat between soldiers

of Ish-bosheth and David In 1004 B.C. David conquered Jerusalem from the Jebusites in 1004 B.C. in a bloodless raid. According to II Samuel and I Chronicles in Bible, the city was taken by Joab, David’s nephew and general, who snuck into the fortress by way of a 40-foot-long tunnel that brought water to the fortress from Gihon Spring.

Dr R. W. L. Moberly of University of Durham wrote for the BBC: “David nobly and movingly laments Saul and Jonathan, leaves the Philistines, and returns to his home territory of Judah where he is made king. It seems that David has 'made it' - with as much success, prosperity, and peace (not to mention several wives and numerous children) as anyone in the ancient world could ever hope for. Yet at this point David becomes complacent. Living "after the Lord's own heart" ceases to be his priority and a terrible unraveling of his achievement sets in. The following chapters tell of David's household falling apart in the pattern of sex and murder that he himself has initiated. [Source: Dr R. W. L. Moberly, University of Durham, [Source: BBC June 25, 2009 |::|]

David built a citadel on a strategically located ridge flanked by deep valleys and made it into the capital of Israel. He chose the site because it was strategically located over the Jordan Valley, about halfway between the northern and southern Holy Lands. According to the Bible, David built a settlement around the mysterious "Millo" and named it “Ir David”, the “City of David” (later it was named “Yerushalayim,” which means "City of Peace" in Hebrew, and is similar to it original Canaanite name).

In David’s time Jerusalem covered a triangular 12-acre piece of land and had a population of around 4,000 people. It was located about 350 feet to the south of modern Old City beyond the eastern ridge called the Ophel.

David's Jewish Kingdom

David ruled from 1000 B.C. to 961 B.C. When David captured Jerusalem he introduced kingship as way of relating God’s purpose to the Jewish people, thereby transferring his covenant with God from himself to the Jewish people. The Second Book of Samuel declares that David “reigned over all Israel and Judah” at Jerusalem: King Hiram of Tyre sent “carpenters and masons, and they built a house for David. And David realized that the Lord had established him as king over Israel, and that He had exalted his kingdom for the sake of His people Israel."

Under David and his successors, Judaism was developed and secured. The Jewish kingdom reached its greatest extent under David around 1000 B.C. when it stretched from the Sinai to the Euphrates River and included large chunks of present-day Jordan, Syria, Lebanon and Egypt. Under David and Solomon complex water works were constructed throughout Palestine.

David’s kingdom lasted less than a century but it fulfilled a promise made by God to Abraham (Genesis 15:18): “To your offspring assign this land, from the river of Egypt [in the Sinai] to the great river, the river Euphrates.” Centuries after David’s kingdom was lost, the Prophet Ezekial dreams (47:13-20) of Israel’s exiles returning to a land restored to borders of David’s kingdom. The location of David's Jewish state made its survival dicey at best. Surrounded by such empires as Egypt, Mesopotamia, Babylon, Assyria, Persia, Greece, Rome, the Byzantines, Arabs, Turks and others, Jerusalem became the center of a crossroads for conquerors.

As for the archeological perspective on all this, Draper wrote in National Geographic: While the Bible says David and Solomon built the kingdom of Israel into a powerful and prestigious empire stretching from the Mediterranean to the Jordan River, from Damascus to the Negev, there's a slight problem — namely, that despite decades of searching, archaeologists had found no solid evidence that David or Solomon ever built anything. Absent more evidence, we're left with the decidedly drab tenth-century B.C. biblical world that Finkelstein first proposed in a 1996 paper — not a single great kingdom replete with monumental buildings but instead a scruffy landscape of disparate, slowly gelling powers: the Philistines to the south, Moabites to the east, Israelites to the north, Aramaeans farther north, and yes, perhaps, a Judaean insurgency led by a young shepherd in not-so-dazzling Jerusalem. Such an interpretation galls Israelis who regard David's capital as their bedrock. Many of the excavations undertaken in Jerusalem are financially backed by the City of David Foundation, whose director of international development, Doron Spielman, freely admits, "When we raise money for a dig, what inspires us is to uncover the Bible — and that's indelibly linked with sovereignty in Israel." [Source: Robert Draper, National Geographic, December 2010]

"Our claim to being one of the senior nations in the world, to being a real player in civilization's realm of ideas, is that we wrote this book of books, the Bible," Daniel Polisar, president of the Shalem Center, an Israeli research institute, told National Geographic. "You take David and his kingdom out of the book, and you have a different book. The narrative is no longer a historical work, but a work of fiction. And then the rest of the Bible is just a propagandistic effort to create something that never was. And if you can't find the evidence for it, then it probably didn't happen. That's why the stakes are so high."

David’s Later Years

Dr R. W. L. Moberly of University of Durham wrote for the BBC: David the great king finally appears as a rather pathetic old man, shivering uncontrollably in bed, while his court and family manoeuvre and jockey for position around the dying king. A power struggle between supporters of two of David's sons, half-brothers to each other, Adonijah and Solomon, ends with Solomon on the throne and some rather dismal settling of scores (1 Kings 1-2). The political wheelings and dealings have a hardy perennial feel to them. [Source: Dr R. W. L. Moberly, University of Durham, [Source: BBC June 25, 2009 |::|]

Larue wrote: “The interpretation of Sheba's rebellion (ch. 20) presents something of a problem. Despite David's generosity in forgiving his enemies, a number of persons from the southern kingdom of Judah were not sure of David's attitude toward them because they had supported Absalom. David urged the Judaeans to welcome him as king (19:11 ff.). Whether it was caused by jealousy over this action, or perhaps by the belief of a rebellious group of Israelites that there was still a chance to break away from Davidic rule, is not clear, but Sheba led the northern tribes in rebellion. His war cry was a call for independence: "We have no portion in David, and we have no inheritance in the son of Jesse, every man to his tents, O Israel." David commissioned his new commander, Amasa, to rally Judaean troops, but he was so slow in executing this responsibility that David turned again to Joab and his mercenaries. Joab murdered Amasa and pursued Sheba to the far northern city of Abel. Here Sheba died at the hand of his own people who decided that it was better that one man should die than the whole town suffer, and for a time the rebellious mood of Israel was quiet. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

“Now the Philistines attacked, on the assumption that the trouble within the Hebrew kingdom had weakened David's power. David participated in one battle but he had neither the strength nor the stamina for warfare. His men sent him back to Jerusalem and carried on without him (21:15-22). A further summary of the Philistine battles and a list of warriors who participated is given in 23:8-39.

At this point, two intrusions interrupt the narrative. The first, Chapter 22, is a psalm identical to Ps. 18. According to the superscription (vs. 1), David sang this song on being saved from Saul. However, the psalm appears to be a national hymn of thanksgiving from dire distress used in some cultic celebration. The poem reflects the time when the temple had been erected (vs. 7) and when the Davidic line had been established (vs. 50-51), so it comes from a later period than David's time. The second intrusion consists of the first seventeen verses of Chapter 23 in which an oracle pertaining to the kingship is attributed to David, giving David the status of an inspired person. This passage is from a later time.

“The Davidic story continues in I Kings. The opening verses demonstrate that the Hebrew monarchy was like that in surrounding cultures wherein the life and health of the nation was reflected in the physical well-being of the ruler. Not only was it important that the king be a person of strength and beauty,14 but he had to be a man of sexual vigor and potency, for the reproductive power of the monarch symbolized the blessings of fertility for the land and flocks. Because David was impotent, Abishag, the young Shunamite maiden was brought to court in the hope that she might stimulate him sexually.15 When she was unable to arouse him, David's kingdom was threatened.

“Adonijah, David's son, was aware of the monarch's impotency and chose this moment to seek the throne, enlisting the help of Joab and Abiathar, the priest (1:8). An enthronement feast was held at the shrine at En-rogal near Jerusalem, to which David's sons (except Solomon) and those who could be counted upon for support were invited. The omission of Solomon from the invited guests would indicate that Adonijah was aware of the political aspirations of Bathsheba and her son. Nathan, the prophet, reported the coup to Bathsheba, and together they plotted the means whereby Solomon could become king. They convinced the aged king that he had promised the crown to Solomon (a promise not noted before) and, revealing Adonijah's plans, persuaded David to have Solomon crowned co-regent. Riding upon the royal she-mule and accompanied by the priest Zadok and the prophet Nathan, Solomon went to Gihon, close to the city of Jerusalem, and was anointed king. In triumph he returned to Jerusalem, and Adonijah, hearing the news, knew his cause was lost. In fear of reprisal, Adonijah sought sanctuary in the shrine at En-rogal, clinging to the horns of the altar.16 Solomon spared Adonijah's life, asking only a promise of loyalty (1:53). Without further difficulty, Solomon joined his father upon the throne of the Hebrew kingdom.

“The last days of David are recorded in the first twelve verses of I Kings, Chapter 2. The failing monarch required promises from Solomon that both Joab and Shimei would be put to death, and that the family of Barzillai, the Gileadite, would be rewarded because of the aid it had given to David when Absalom had revolted. Much has been written on these verses by scholars, with some arguing that the passages are to be treated as a late addition17 with others justifying David's wish on the basis of the Hebraic belief in the importance of the practice of blood revenge,18 and with still others using the passages to reveal the vindictiveness of the ailing king who, having failed to settle his own accounts, passed the responsibility on to his son.19 The accounts seem to be designed to remove the stigma attached to Solomon for the way in which he brought about consolidation of the empire by the removal of potential rivals. The stories protect Solomon's reputation and explain the deaths of Shimei and Joab as the fulfillment of a deathbed wish of David.

Myths and Misconceptions About David’s Rule

enigmatic phrase "Davidic altar-hearth" in the Mesha stele

Dr R. W. L. Moberly of University of Durham wrote for the BBC: “However, closer examination of the Samuel account suggests that there was a lot more to David's rule than meets the eye. The Near East of 1000 BC was a lawless place and some Biblical academics are convinced that many of the explanations and alibis which appear in the ancient account of David's life indicate that he was a ruthless leader whose reign was riddled with assassinations, subterfuge and double-dealing. Even the famous battle with the great Philistine Goliath fails to stand up to closer scrutiny. [Source: Dr R. W. L. Moberly, University of Durham, [Source: BBC June 25, 2009 |::|]

“David, it appears, was not the naïve shepherd boy at the time of the infamous duel, but an experienced apprentice-warrior. His sling wasn't simply a tool for sheep herding but was also a deadly military weapon, the exocet of the ancient world. “If Goliath was as tall as the Bible claims then he would probably have been suffering from a growth condition called pituitary gigantism, which has debilitating side-effects including tunnel-vision. So perhaps David's victory wasn't quite so implausible after all. When the factors are taken into consideration it is increasingly likely that it was actually Goliath who was at a disadvantage. |::|

“David was undoubtedly a great leader, but recent evidence and analysis is providing far more complex interpretations of his life. This documentary reveals that by looking beyond the two-dimensional image of the tenacious shepherd boy who became king, we can now see a far more complicated, fascinating man; a fallible and sometimes ruthless pragmatist.” |::|

David's Significance: a Successful King

“Dr Paula Gooder of the Queen's Foundation in Birmingham, wrote for the BBC: “One of the reasons David is so successful as a king is that he weaves the relationship with God into the very life of the people. So when David establishes his capital in Jerusalem he establishes it with the Ark of the Covenant. One of the most important features of the establishment of the capital is that the Ark of the Covenant is taken in a joyful procession into the capital. So the capital becomes not only the political heart of the nation but also the religious heart of the nation. [Source: “Dr Paula Gooder, tutor at the Queen's Foundation in Birmingham, BBC June 25, 2009 |::|]

“David, however, does not build a temple, because he is told by God that he is not the person who is called to build it: it's his son Solomon who will build the temple. Nevertheless David establishes the worship of God in a single place. This is very important because until this point God has been worshipped wherever the Ark of the Covenant is, and the Ark of the Covenant moves round wherever the leaders of the people are based, so it is discovered in various different places in Israel. |::|

“David places the Ark of the Covenant in a single place in the capital, and it is there that the people must come to worship God. David's capital is so successful because the people have to come and worship God in the one place. It's as though David gives those twelve disparate tribes a focus that they can all look to. They can come and worship and have their political life at the centre of the nation.” |::|

David's Relationship with God

David's sacrifice on Mount Moriah

Nick Page, author of The Bible Book and The Tabloid Bible” wrote for the BBC: “By the time of David, God is in some ways a more distant figure from His people, and in other ways He's a lot closer. Physically, he's more distant. He doesn't seem to appear in the way that He appeared before Moses and certainly the way He appeared before Abraham, when he came to them as a figure. When God appears in the time of David, it's as a cloud filling the temple. It's a much more ethereal kind of presence. |::|

“Nevertheless he seems to speak as directly as before, if not more so. The way that David talks about God, if we take the Psalms of David as representative of his thought, is closer and much more personal than in previous times. Although Abraham and Moses both argued with God, David pleads with God. He cajoles Him, he upbraids Him for not doing things. |::|

“The Psalms really are like a spiritual diary. There's a sense of closeness with God, the ability to question Him, to ask what's going on and to have the faith that He'll sort it out. And to have a very kind of personal relationship with God, whilst at the same time God is certainly not present in the same way that He was in the time of Moses. |::|

“David was a great king - the greatest king in Israel's history - despite what he did rather than because of what he did. His greatness is shown through his humanity, through his weakness, through his vulnerability. But for his willingness that even though he was a king, to come before God, just as a human being, and say "sorry".

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, Live Science, Archaeology magazine, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024