Home | Category: Ancient Hebrews and Events During Their Time / Ancient Hebrews and Events During Their Time

FIRST HEBREWS

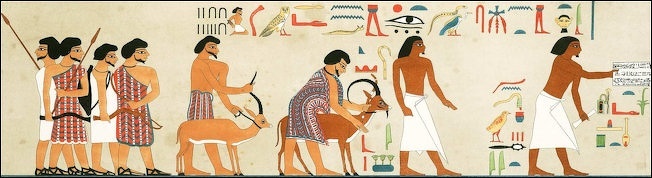

Ancient Egypytian depction of a Berber, Nubian, Asiatic (maybe Hebrew) and Egyptian

The first Hebrews were a nomadic tribe of pastorialists who lived almost entirely off their herds of goats, sheep and cattle. They were Semitic pagan nature worshippers that wandered the deserts between Mesopotamia and Egypt. Some scholars state that Jews embraced monotheism because when they settled in Israel — a lush place before the time of Christ — where their survival was less dependant on the whims of nature, allowing them to focus their attention more on creating a unified civilization.

The Near East at the time of the first Jews was a time of chaos. The Bronze Age was ending and the Iron Age was emerging and the Near East was a patchwork of rival kingdoms that included the Israelites, Jebusites, Amorites, Ammonsites, Hittites, Horvites and Philistines. The Assyrians and Phoenicians were rising, Egypt was in a temporary state of decline, and the Mycenaeans were fighting the Trojans in the Trojan War.

Historical dates around the time the Hebrews emerged

ca. 1200-1000 B.C.: Jerusalem is a Canaanite city

ca. 1150-900 B.C.: Middle Babylonian period:

ca. 1106 B.C.: Deborah judges Israel.

ca. 1100 B.C.: The Philistines take over Gaza. They called it Philistia (from which the modern name Palestine is derived), and made it one of their civilization's most important cities.

ca. 1050-450 B.C.: Hebrew prophets (Samuel-Malachi)

[Source: Jewish Virtual Library, UC Davis, Fordham University]

Websites and Resources: Virtual Jewish Library jewishvirtuallibrary.org/index ; Judaism101 jewfaq.org ; torah.org torah.org ; Chabad,org chabad.org/library/bible ; Yivo Institute of Jewish Research yivoinstitute.org ; Bible and Biblical History: ; Biblical Archaeology Society biblicalarchaeology.org ; Bible History Online bible-history.com Bible Gateway and the New International Version (NIV) of The Bible biblegateway.com ; King James Version of the Bible gutenberg.org/ebooks ; Jewish History: Jewish History Timeline jewishhistory.org.il/history Jewish History Resource Center dinur.org ; Center for Jewish History cjh.org ; Jewish History.org jewishhistory.org ; Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Where God Came Down” by Joel P. Kramer Amazon.com ;

“Archaeology of the Bible: The Greatest Discoveries From Genesis to the Roman Era”

by Jean-Pierre Isbouts Amazon.com ;

“Unearthing the Bible: 101 Archaeological Discoveries That Bring the Bible to Life” Amazon.com ;

“Zondervan Handbook of Biblical Archaeology: A Book by Book Guide to Archaeological Discoveries Related to the Bible” by J. Randall Price and H. Wayne House Amazon.com ;

“NIV, Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible (Context Changes Everything) by Zondervan, Craig S. Keener Amazon.com ;

“The Bible Unearthed” by I. Finkelstein and N. Asher Silberman Amazon.com ;

“Egypt, Canaan and Israel in Ancient Times” by Donald Redford Amazon.com ;

“Oxford Companion to the Bible” by Bruce M. Metzger and Michael David Coogan Amazon.com ;

“The Bible as History” by Werner Keller Amazon.com ;

“Historical Atlas of the Holy Lands” by K. Farrington Amazon.com ;

“The Story of the Jews” Volume One: Finding the Words 1000 BC-1492 AD by Simon Schama (Author) Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Jews” by Paul Johnson, Amazon.com ;

Early Hebrews in Israel

Canaanite God Resheph Semitic tribes probably arrived in Palestine, known in the early days as Canaan (modern-day Syria. Lebanon, the West Bank, Jordan and Israel) at a very early date. Some scholars believe that Hebrews arrived in Canaan around 2000 B.C. Other scholars believe they arrived around 1200 B.C.

Most scholars believe the Hebrews did not conquer Canaan with a sudden military campaign as is depicted in the Bible but rather arrived in the region through the slow infiltration of semi-nomadic people from the desert. Some believe the Hebrews originally came from Egypt, and this gave birth to the Exodus story. In Canaan they settled among other Semitic peoples. Around the time the Hebrews were thought to have arrived the forests on the slopes of the Judean and Samaritan hills were quickly cut down and converted the slopes into irrigated terraces. The people that lived in Israel at that time practiced institutionalized slavery.

Other scholars believe that the first Israelites evolved out of people already with Canaan. They suggest that they were shepherd and herders who began forming their own communities in the hills outside the major towns. As they expanded they fought with other tribes in the area over water rights, which might have provided the historical kernels for the battles described in Joshua and Judges.

The fight for possession of Palestine today often draws on history to stake its claims. Jews often asserts their connection Abraham who arrived around 2000 B.C. The Palestinians have asserted they are the modern-day successors the Canaanites, who lived in Palestine before Abraham arrived. The aim of both sides is to show they were there first. Neither side has any historical or archaeological evidence to back up their claims.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT HEBREWS IN PALESTINE-ISRAEL africame.factsanddetails.com

Origin of the Hebrews According to the Bible

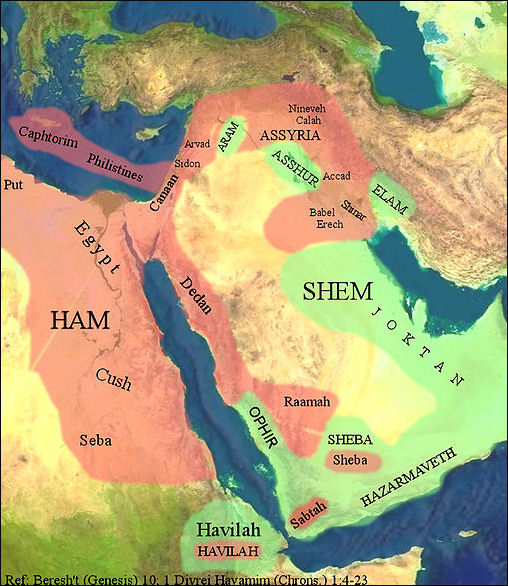

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “According to biblical tradition, the Hebrews are peoples descended from Shem, one of Noah's sons, through Eber, the eponymous ancestor, and Abraham. Gen. 7:22 f., reports that the flood destroyed all life except that in Noah's ark; consequently, the whole human family descended from Noah and his sons: Japheth, Ham and Shem. As yet, not all of the names of eponymous ancestors in the family lines can be identified,1 but some probabilities are listed in Chart 6. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

“From Shem, through Arpachshad and Shelah came Eber, the eponymous ancestor of the Hebrews, and from his descendants through Peleg, Reu, Sereg and Nahor came Terah, the father of Abram and his brothers Nahor and Haran. It becomes clear that if "Hebrews" are descendants of Eber, then others besides those of Abraham's line would be included (see Gen. 10:25-27).

“A somewhat different tradition of Hebrew beginnings is reflected in Ezek. (16:3 ff.), where mixed ancestry - Amorite, Hittite and Canaanite - is attributed to the Jerusalemites. But here we have a unique situation, for Jerusalem was a Jebusite stronghold which did not become a Hebrew city until the time of David (II Sam. 5). The firstfruits liturgy (Deut. 26:5) traces Hebrew ancestry to the Aramaeans, but the designation appears to be used in a broad rather than a specific sense.

“Perhaps the best that can be said is that the Hebrews of the Bible appear to be one branch of the Northwest Semitic group, related linguistically to Canaanites, Edomites and Moabites, who moved from a semi-nomadic existence to settled life in the Bronze Age.

Map of the Middle East in early Biblical Times

Etymological Analyses of the Term "Hebrew”

The name Hebrew (Irvi) is believed by some to be derived from the root meaning “to cross” and refers to people who came to Canaan from the eastern side of the Euphrates. It is also associated with the name Ever, grandson of Shem. 'Shem' is the root of the word 'Semite.'

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “Etymological analyses of the term "Hebrew" ( 'ibri) have given little help to the study of origins. The term has been related to a root, meaning "to go over" or "to go across"; hence, a "Hebrew" would be one who crossed over or one who went from place to place, a nomad, a wanderer, a designation that would fit some aspects of patriarchal behavior. A similar term, habiru, is found in cuneiform documents from the twentieth to the eleventh centuries, often used interchangeably with another word, SA.GAZ. At times the Habiru appear to be settled in specific locations; at times they serve in the army as mercenaries, or are bound to masters as servants. The El Amarna tablets refer to invaders of Palestine as 'apiru, a word bearing close relationship to the terms habiru and "Hebrew." [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

“Extensive research has led many scholars to the conclusion that the term "Hebrew" was first used as an appellative to describe foreigners who crossed into settled areas and referred not to a specific group but to a social caste. If the word "Hebrew" parallels habiru or 'apiru, we know that these people on occasion were employed, at times created settlements of their own, and at other times attacked established communities. The suggestion that the terms 'apiru, habiru and "Hebrew" relate to those who have renounced a relationship to an existing society, who have by a deliberate action withdrawn from some organization or rejected some authority, and who have become through this action freebooters, slaves, employees or mercenaries presents real possibilities. In the Bible the word Hebrew becomes an ethnic term used interchangeably with "Israelite."

Abraham and the Hebrews According to the Bible

Abraham

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “With Abraham the story of the Hebrews begins, and it is clearly stated that Hebrew origins lay outside Canaan. The summons to leave his ancestral home and journey to Canaan is accompanied by a promise (Gen. 12:2) that becomes a submotif in patriarchal accounts, re-appearing again and again (cf. Gen. 13:14 f., 15:5 f., 18:10, 22:17, 26:24, 28:13 f., 32:12 f., 35:9 ff., 48:16), finally taking covenantal form (Gen. 17:14 ff.). The promise has two parts: nationhood and divine blessing or protection. The precise location of the nation-to-be is not specified but was, of course, known to those hearing or reading the account. The promise of blessing signified the unique and particularistic bond between Yahweh and his followers, so that the enemies of Abraham or the nation were enemies of Yahweh, and those befriending Abraham and/or the nation would be blessed. With this assurance, Abraham journeyed to Canaan, Egypt, the Negeb, Hebron, Gezer, Beer-sheba and back to Hebron where he and his wife Sarah died. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

“The descriptions of Abraham are not uniform: at times he appears as a lonely migrant, at others as a chieftain, head of a large family, or as a warrior. Factual details about the patriarch are difficult to establish, for his real significance lies in what is often called "inner history," through which those who looked to Abraham as a forefather gained understanding of themselves as "people of the promise" and attained, a sense of destiny and an appreciation of their particular relationship to their deity. We have noted earlier that some Abrahamic traditions coincide with information coming from Nuzi, which would place Abraham in the Middle Bronze era.

“We read that Abraham, in response to a divine summons, left Mesopotamia and journeyed to Canaan with his wife, Sarah, and nephew, Lot. It is clear that the people were meant to recognize themselves as a community originating in a commission from God and in the unwavering, unquestioning obedience of Abraham. The journey itself was more than a pilgrimage, for it constituted the starting point of a continuing adventure in nationhood. Nor are the travelers without vicissitudes, but throughout famine, earthquake, fire and war, they are protected by Yahweh.

“Gen. 14, in which Abraham is called a "Hebrew" for the first time, records a battle between the patriarch and kings of countries or areas as yet unidentified for certain and associates him with the Canaanite king of Jerusalem. It is possible that reliable historical data are preserved here.2 The account of the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah may also rest in some memory of a shift in the earth's crust that destroyed the cities of the plain. Tradition associates Abraham with Hebron, and if Jebel er-Rumeide is the site of this ancient city, it is evident that a powerful city was located here in the Middle Bronze period.3

“Abraham's adventures in the Negeb, the problems of grazing and watering rights, and the digging of a well at Beer-sheba4 echo genuine problems of the shepherd. The episode involving Sarah and King Abimelech (a doublet of Gen. 12:10 ff.) introduces Sarah's relationship to Abraham as both wife and sister, a relationship which in Hurrian society provided the wife with privileged social standing. It may also be interpreted as an historic link with the cultures of the upper Euphrates.”

Biblical Stories of Ishmael, Jacob and Joseph and the Hebrews

Hager and Ishmael in the Wilderness

Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “The close relationship between the Hebrews and the people of the desert and steppes is recognized in the story of Ishmael, the nomadic first son of Abraham; but it is through Isaac, the second son about whom so very little is recorded, that the Hebrews trace their own family line. Both Isaac and his son Jacob maintain a separateness from the people among whom they dwell, taking wives from among their own kin in Haran (Gen. 24; 28). The story of Jacob, who becomes Israel, and his twin brother Esau, who becomes Edom, is colored with rivalry, trickery and bitter misundertanding but also contains echoes of Hurrian custom. In Hurrian law, birthright could be purchased, and some of the terminology associated with Isaac's blessing of his sons reflects Hurrian patterns. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

“The stories about Jacob also accord with Nuzi (Hurrian) law for it is recorded that a man may labor for his wife. In dealing with his uncle Laban, Jacob's trickery was matched by his uncle's deceptive acts. There is no condemnation of chicanery but, rather, the attitude that to best a man in a business contract revealed cleverness. When Jacob's hopes to inherit his uncle's estate were dashed by the birth of male heirs, he broke contract and fled, and it was only when a new contract was made that relationships were healed. The account of Jacob's night wrestling with an angelic visitor has probably come down to us through various recensions, for it now contains two aetiological explanations: one concerning the name "Jacob-Israel" and the other giving the reason why the ischiatic sinew is not eaten by Hebrews. Other traditions associate Jacob with Bethel and Shechem.

“Joseph, the son of Jacob, was sold into slavery by jealous brothers and rose to high office in Egypt. When his father and brothers migrated to Egypt to escape famine, they were regally received and encouraged to settle. Documents attesting to the custom of admitting nomadic groups into the country in time of famine are known from Egypt, and the Joseph stories reflect many accurate details about Egyptian life and may be derived in part from Egyptian tales, as we shall see. The pharaoh under whom Joseph rose to power is not identified.

“It is quite possible, as A. Alt has argued, that the patriarchs were founders of separate cults or clans in which distinctive names for the deity were compounded with patriarchal names.8 Hence, the deity was known as "the Shield of Abraham" (Gen. 15:1), "the Fear of Isaac" (Gen. 31:42, 53), and "the Mighty One of Jacob" (Gen. 49:24). Individual representations were later fused and equated with Yahweh, and individual clan heroes were placed in an historical sequence and made part of a single family line from Abraham to Jacob (Israel).”

Problems with Dates and Places with the Hebrews and the Bible

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “Efforts to date the patriarchal period have not been particularly rewarding, for biblical chronology is complex. In the P source, 215 years pass between the time of Abraham's journey to Canaan and Jacob's migration to Egypt (see Gen. 12:4b, 21:5, 25:26, 47:9), and the period spent in Egypt is given as 430 years (Exod. 12:40 f.), making a total of 645 years before the Exodus. As we shall see, most scholars date the Exodus near the middle of the thirteenth century, so that Abraham would leave Mesopotamia at the beginning of the nineteenth century, and Jacob's journey to Egypt would occur about 1700 B.C. Unfortunately, date variations occur in some manuscripts. In the LXX, Exod. 12:40 includes time spent in both Egypt and Canaan in the 430-year period (some manuscripts read 435 years). According to this reckoning, Abraham's journey would fall in the seventeenth century and Jacob's in the fifteenth century. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

“The early nineteenth century date for Abraham places his departure from Mesopotamia at the time of the Elamite and Amorite invasion. It harmonizes with the conclusions of Nelson Glueck, who found that between the twenty-first and nineteenth centuries B.C. the Negeb was dotted with hamlets where inhabitants, having learned how to hoard water, engaged in agriculture and tended small flocks. Such settlements would provide stopping places for Abraham and his retinue.9 The seventeenth century date for Jacob's settlement in Egypt coincides with the Hyksos invasion of Egypt, lending support to Josephus' hypothesis, for Hebrews may have been part of this movement.

“The second pattern of dating would place Abraham in the time of Hammurabi of Babylon and would give strength to the argument that the mention of King Amraphel of Shinar in Gen. 14:1 is a Hebraized reference to Hammurabi. Abraham would, therefore, be in Canaan during the Hyksos period, and Joseph would have risen to power in the Amarna age. The close of the Amarna period brought to power leaders hostile to Akhenaton and possibly also to those he had favored.

“Whatever the correct date for Abraham may be, he represents the beginning of the nation to the Hebrews. Yahweh's promise to the patriarch and his successors is considered to be the guarantee of national existence (Num. 32:11). There are no references to Abraham in the writings of the eighth century prophets, for then stress was laid on the Exodus as the starting point of the nation. In the seventh and sixth centuries, and in the post-Exilic period, the Abrahamic tradition came to the fore once again.

“Efforts to determine the date and route of the Exodus have been disappointing. Josephus placed the Exodus at the time of the overthrow of the Hyksos by Ahmose in the sixteenth century, a date that is far too early. Biblical evidence is limited. I Kings 6:1 reports that Solomon began building the temple in the fourth year of his reign, 480 years after the Exodus. Solomon's rule is believed to have begun near the middle of the tenth century, possibly about 960 B.c. Thus, the date of the Exodus would be: 960 minus 4 (4th year of reign) plus 480, or 1436. In that case, Thutmose III would be the pharaoh of the oppression, and his mother, Hatshepsut, might be identified as the rescuer of the infant Moses. The Hebrew invasion of Canaan, taking place forty years later or about 1400 B.C., might be identified with the coming of the 'apiru.10

“Another theory is based on the reference to the building of Pithom and Raamses in Exod. 1:11. It was noted earlier that both Seti I and Rameses II worked at the rebuilding of these cities, and that Rameses is the best candidate for the Pharaoh of the Exodus (1290-1224 B.C.). If the Exodus took place between 1265 and 1255, the invasion of Canaan would occur in Mernephtah's reign, and some encounter between Egyptians and Hebrews would be the basis for his boast of annihilating Israel.

Hebrew Life and Society

Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “It is clear from biblical tradition that, at the beginning of their history, the semi-nomadic Hebrews with flocks of sheep and goats were at the point of moving into a settled way of life. The patriarchs are chiefs of large families or clans living, for the most part, in peace among their neighbors with whom they enter covenants. From family and clan beginnings came tribes linked to one another by ancestral blood ties. Bonds between clans or tribes were so strong that the group might be described as having an existence of its own, a personality embodying the corporate membership. This phenomenon of psychic unity, labeled "corporate personality" by H. Wheeler Robinson,placed particular responsibilities upon each member of the group. Because group life was a unity, injury to a single member was injury to all demanding repayment by the next of kin, the go'el. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

Egyptian depiction of Asiatics (probably Canaanites, possibly Hebrews)

“Blood shed was tribal blood requiring redemption by the next of kin. Should a man die without offspring, his next of kin had to bring the widow to fruition, and the child born to her became the child of the dead man, the one carrying his name (Ruth 4:4-10). As the father was at the head of the family, so the tribal chief and elders led the larger group, seeking the well-being, peace and psychic health of the members. The corporate nature of the group afforded great protection, for wherever a member went, he was backed by the strength of the tribe to which he belonged. Fear of reprisal tended to be - but was not always - a restraining factor in violation of social mores (Judg. 19-20). When the head of the household died, the widow and orphan were cared for by the next of kin and ultimately by the total group.

“Tribal and family religion centered in holy places where a local priesthood tended shrines, kept altar fires burning, and shared in offerings (I Sam. 2:12-17). The father seems to have acted as ministrant on behalf of the family (I Sam. 1). Offerings were made and a meal shared through which the participants were bound more firmly together. There is no evidence that the deity was believed to participate in the meal. Agreements made at holy places were witnessed by the deity who guaranteed fulfillment of terms (Gen. 31:51 ff.). The shrine of Ba'al-berith (Judg. 9:4) or El-berith (Judg. 9:46), the "covenant god" at Shechem, may have been a holy place where covenants were made in the presence of the god.

“An important custom in Hebrew society was the practice of hospitality. A guest was honored and entertained, even at considerable expense to the host (Gen. 18:1-8, 24:28-32). Once under the host's roof, or having shared food, the guest was guaranteed protection (Gen. 19, Judg. 19). Should a stranger settle in the community, he enjoyed most of the rights and responsibilities.

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons, Schnorr von Carolsfeld Bible in Bildern, 1860

Text Sources: Internet Jewish History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Old Testament Life and Literature” by Gerald A. Larue, New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Wikipedia, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024