Home | Category: The Torah / The Old Testament

WHO WROTE ON THE BIBLE?

Did Moses write the first part of the Bible?

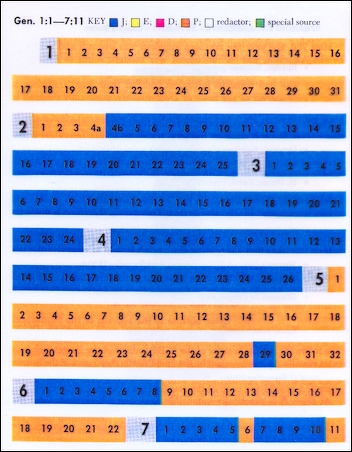

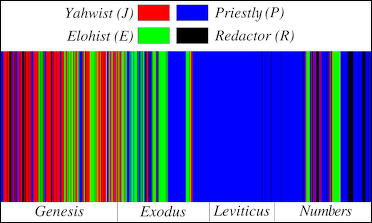

Matti Friedman of Associated Press wrote: “For millions of Jews and Christians, it's a tenet of their faith that God is the author of the core text of the Hebrew Bible _ the Torah, also known as the Pentateuch or the Five Books of Moses. But since the advent of modern biblical scholarship, academic researchers have believed the text was written by a number of different authors whose work could be identified by seemingly different ideological agendas and linguistic styles and the different names they used for God. [Source: Matti Friedman, Associated Press, June 30 2011 ***]

“Today, scholars generally split the text into two main strands. One is believed to have been written by a figure or group known as the "priestly" author, because of apparent connections to the temple priests in Jerusalem. The rest is "non-priestly." Scholars have meticulously gone over the text to ascertain which parts belong to which strand. ***

“Over the past decade, computer programs have increasingly been assisting Bible scholars in searching and comparing texts, but the novelty of the new software seems to be in its ability to take criteria developed by scholars and apply them through a technological tool more powerful in many respects than the human mind,” said Michael Segal of Hebrew University's Bible Department. ***

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Who Wrote the Bible?” by Richard Friedman, Julian Smith, et al.

Amazon.com ;

“The Torah: The Five Books of Moses, the New Translation” by the Jewish Publication Society Inc. (Editor) Amazon.com ;

“Commentary on the Torah” by Richard Elliott Friedman Amazon.com ;

“The Torah: A Modern Commentary” by Gunther Plaut Amazon.com ;

“JPS Hebrew-English TANAKH” (Hebrew Bible) by Jewish Publication Society Inc. Amazon.com ;

“The Hebrew Bible: A Translation with Commentary” (audiobook) by Robert Alter, Edoardo Ballerini, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Holy Bible in English easy to read version” Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Bible: The Story of the World's Most Influential Book”

by John Barton, Ralph Lister, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Complete Guide to the Bible” by Stephen M. Miller Amazon.com ;

“The Talmud” by H Polano and Reverend Paul Tice Amazon.com ;

“Everyman's Talmud: The Major Teachings of the Rabbinic Sages” by Abraham Cohen

Amazon.com

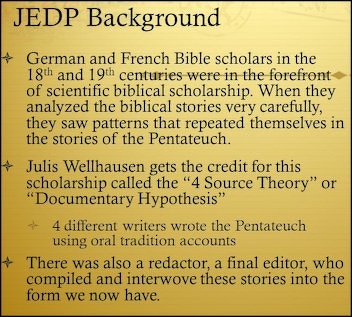

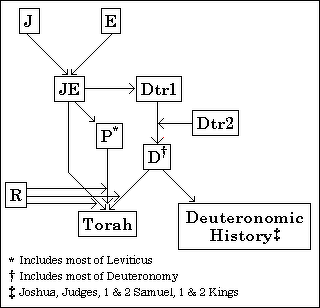

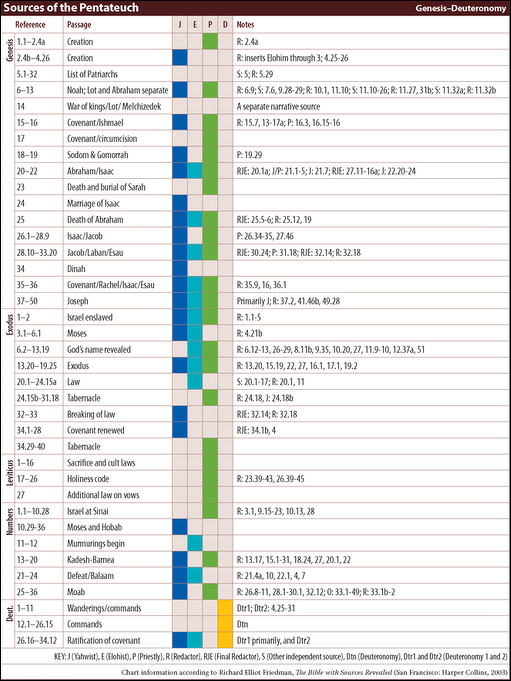

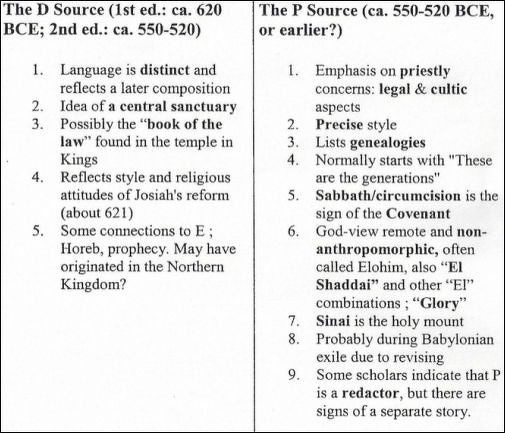

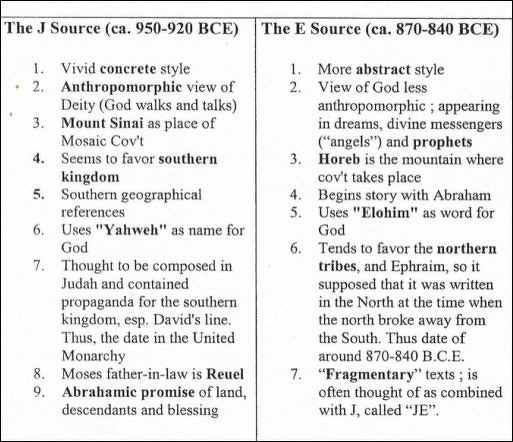

Documentary Hypothesis (Graf-wellhausen Theory)

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “The thesis known as the Graf-Wellhausen theory, or as the Documentary Hypothesis, still provides the basis upon which more recent hypotheses are founded. The Graf-Wellhausen analysis identified four major literary sources in the Pentateuch, each with its own characteristic style and vocabulary. These were labeled: J, E, D and P. The J source used the name "Yahweh" ("Jahveh" in German) for God, called the mountain of God "Sinai," and the pre-Israelite inhabitants of Palestine "Canaanites," and was written in a vivid, concrete, colorful style. God is portrayed anthropomorphically, creating after the fashion of a potter, walking in the garden, wrestling with Jacob. J related how promises made to the patriarchs were fulfilled, how God miraculously intervened to save the righteous, or to deliver Israel, and acted in history to bring into being the nation. E used "Elohim" to designate God until the name "Yahweh" was revealed in Exod. 3:15, used "Horeb" as the name of the holy mountain, "Amorite" for the pre-Hebrew inhabitants of the land, and was written in language generally considered to be less colorful and vivid than J's. E's material begins in Gen. 15 with Abraham, and displays a marked tendency to avoid the strong anthropomorphic descriptions of deity found in J. Wellhausen considered J to be earlier than E because it appeared to contain the more primitive elements. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,”1968, infidels.org ]

“The Deuteronomic source, D, is confined largely to the book of Deuteronomy in the Pentateuch, contains very little narrative, and is made up, for the most part, of Moses' farewell speeches to his people. A hortatory and emphatic effect is produced by the repetition of certain phrases: "be careful to do" (5:1, 6:3, 6:25, 8:1), "a mighty hand and an outstretched arm" (5:15, 7:19, 11:2), "that your days may be prolonged" (5:16, 6:2, 25:15). Graf had demonstrated that knowledge of both J and E were presupposed in D, and having accepted DeWette's date of 621 B.C. for D, argued that J and E must be earlier. J was dated about 850 B.C. and E about 750 B.C.

“The Priestly tradition, P, reveals interest and concern in whatever pertains to worship. Not only does P employ a distinctive Hebrew vocabulary but, influenced by a desire to categorize and systematize material, develops a precise, and at times a somewhat labored or pedantic, style. Love of detail, use of repetition, listing of tribes and genealogical tables, does not prevent the P material from presenting a vivid and dramatic account of Aaron's action when an Israelite attempted to marry a Midianite woman (Num. 25:6-9) or from developing a rather euphonious and rhythmical statement of creation (Gen. 1). The Graf-Wellhausen hypothesis noted that P contained laws and attitudes not discernible in J, E, or D and reflected late development. P was dated around the time of Ezra, or about 450 B.C.

“The combining of the various sources was believed to be the work of redactors. Rje, the editor who united J and E around 650 B.C. provided connecting links to harmonize the materials where essential. Rd added the Deuteronomic writings to the combined JE materials about 550 B.C., forming what might be termed a J-E-D document. P was added about 450-400 B.C. by Rp, completing the Torah. This hypothesis, by which the contradictions, doublets, style variations, and vocabulary differences in the Pentateuch were explained, can best be represented by a straight line.

“Variations in the Graf-Wellhausen theory have been proposed since it was first expounded in the nineteenth century. Research into the composition of the individual documents produced subdivisions such as J1, J2, J3, etc. for J, and El, E2, and so on, for E until the documents were almost disintegrated by analysis. New major sources were recognized by other scholars. Professor Otto Eissfeldt discovered a fifth source beginning with Gen. 2 and continuing into Judges and Samuel which he labeled "L" for "Lay" source. R. H. Pfeiffer of Harvard University identified an "S" source in Genesis, so labeled because Pfeiffer believed it came from Seir (in Edom) or from the south. The great Jewish scholar, Julian Morgenstern, singled out what he believed to be the oldest document, "K," which, while in fragmentary form, preserved a tradition of Moses' relationships with the Kenites. Martin Noth of Germany argued for a common basic source "G" (Grundlage for "ground-layer" or "foundation") upon which both J and E are developed.”

Outline of Documentary Hypothesis Authors:

J: Pro-Judah; anti-Israel, their rival. Less interested in Moses.

E: Pro-Israel; anti-Judah, their rival. Pro-Moses; Anti-Aaron.

D: Pro-King Josiah. Ironically, Josiah's kingdom collapses 20 years later. They blame the collapse on a previous king, King Manasseh, Josiah's grandfather, so Josiah doesn't take the blame for the collapse of his own kingdom.

P: Written as an alternative to JE. Pro-Priests, specifically the priests who claim to be descended from Aaron. Against rival priests who claim to be descended from Moses.

R: Redactor. J & E were put together earlier to create JE. The Redactor combined JE, D,

& P, adding just a few lines of his own to make the transitions smooth. [Source: solarmythology.com/

Book: “Who Wrote the Bible?” by Richard Elliott Friedman (1987) is a good general reference on the Documentary Hypothesis. The book goes into the history and evolution of the J, E, P, and D sources, and shows how they influenced the writing of the first five books of the Bible.

J: Organizer of the Old Testament

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “It has been noted that Solomon's time was marked by great literary activity and, if one can generalize from the Gezer Calendar, literacy may have been widespread. In addition to the material pertaining to the monarchy, the so-called "J" materials came into being. J should not be treated as history, in the modern sense, but rather as a religious saga recounting myths, legends and folktales. How much of J was in written form, gathered and combined prior to this time, cannot be determined. Some legends were probably preserved in oral form as tribal recitations. Certain stories appear to be Hebraized Canaanite shrine legends, for they refer to Canaanite cult objects and some designations suggest shrine deities. Some stories, such as the flood story, can be traced back to Babylonian and Sumerian accounts and were perhaps drawn from Canaanite versions of these stories. A few passages, such as Gen. 4:23-the song of Lamech-come from specific tribal groups. This is to say that the J writer did not originate the material but compiled, edited and reworked sources into a great schematic framework. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,”1968, infidels.org ]

Julius Welhausen

“Three major themes appear to have been combined: 1) Legends and myths pertaining to human beginnings, containing aetiological materials explaining why certain aspects of life are the way they are. 2) Patriarchal narratives demonstrating that Yahweh, the creator of the heavens and earth and all that is within them, was the same deity who miraculously led the fathers of the Hebrew nation and prepared the Hebrew people for their glorious role, rejecting other neighboring groups which became subsidiaries of the Solomonic kingdom (such as the legends about Esau/Edom). 3) The Mosaic tradition leading up to the invasion of Palestine. Within this framework, a pattern can be discerned consisting of a series of waves, with each peak symbolizing a new beginning in Yahweh's relationships with man and each trough representing the miscarriage of the experiment.

“Man is introduced as Yahweh's gardener in Eden, but is expelled when he attempts to become like the deity. Yahweh expunged this poor beginning with the flood and preserved only a righteous remnant, Noah, as the foundation for a new beginning. When Noah's descendants attempted to invade the realm of the divine, Yahweh limited mankind's powers by creating non-co-operating language groups. From one group Yahweh chose Abraham, and when the patriarch's descendants became enslaved in Egypt, a new beginning was made in the Exodus under Moses. Because the people sinned in the desert, they could not enter Palestine. Another new beginning, of which J was a part, is to be seen in the Davidic kingdom, firmly established in J's time in the promised land. If J saw signs portending failure in Solomon's reign, he gives no clear indication in his writings. Another pattern appears in J's implication that Yahweh's efforts to work with mankind in general were unsuccessful, so the deity singled out a specific group to be identified as his own people.”

Historical Clues in J

Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “It is J's concern to indicate that what had occurred in history, in the creation of the Hebrew nation, in the development of wealth and power as experienced under David and Solomon, did not "just happen" but came about through the intervention of Yahweh in human affairs. The present status of the nation could only be appreciated through a theologized version of past tradition. Furthermore, emphasis upon what Yahweh had done in the past dramatized what the relationship of the people to Yahweh in the present should be, for Yahweh was continuing to do in the present what he had done in the past. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,”1968, infidels.org ]

“There can be little doubt that the writer was a Judaean, a learned master of magnificent prose characterized by the direct simplicity of the folktale, the adroit use of adjectives, and the sophisticated wisdom of one who has insight into national destiny. J was proud of the Hebrew kingdom and at times exhibited a spirit of superiority as he looked upon the pre-Hebrew inhabitants of Palestine whom he called "Canaanites" (Gen. 24:3, 37), or revealed his feelings about the Bedouins ("Ishmaelites," Gen. 16:12). At times he appears to have moved toward universalism, but he actually never abandoned the nationalistic, particularistic point of view. Yahweh was the creator of all, but Yahweh was Israel's god and Israel was Yahweh's people. All the nations of all the world will secure blessing-but through Abraham (Gen. 12:3b).

Documentary hypothesis

“While there is absolutely no hint provided as to authorship, it is perhaps not amiss to suggest that the writer was associated with the Temple and that this great saga was used when rites of renewal and rebirth would quite properly call for a recital or dramatization of the creation account,4 perhaps at great religious festivals such as the New Year. Some parts of the narrative may have been used for other festal occasions, such as rites of enthronement in which the allegiance of the nation was pledged to the monarch in the form of a covenant ceremony, blessed and protected by Yahweh. It is doubtful that the saga was set apart for priestly perusal, but any suggestions as to how it may have been used are hypothetical.

“Only a few clues enable scholars to suggest the reign of Solomon as the time of writing. In the first place the Deuteronomic material presumes a knowledge of J so that if the setting of Deuteronomy in the seventh century is correct then J must have been written before that time. In the second place, Gen. 27:40, which deals with Hebrew-Edomite relations suggests by the phrase "and you shall serve your brother" that Edom had been subdued, and according to II Sam. 8 this occurred during the reign of David. The subsequent part of the verse suggests that Edom had broken free from this bondage, and it has been suggested that this may have taken place in Solomon's reign when Hadad led a rebellion (I Kings 11:14-25). The only other times when an Edomitic revolt is noted are in the ninth century during the reign of Jehoshaphat when, according to I Kings 22:47, Edom was ruled by a deputy (cf., however, II Chron. 20), or during the reign of Jehoram (second half of the ninth century) when Edom won freedom (II Kings 8:20), thus giving a ninth century date for J. Because there is no hint of the division of the Hebrew kingdom into independent northern and southern units, it would seem that J should be dated in the tenth century. The physical abundance depicted in the "blessing of Jacob" (Gen. 49) and the twelve-tribe pattern also seem to reflect Solomon's era.

“The following list of passages indicates those forming the core of the J saga. To read these passages without reference to the material which was later added to expand and amplify the stories is difficult, for the gaps that appear in the development of the theme are sometimes due to the incorporation of significant themes in the sections treated as additions. For example, in the Moses cycle the persecution of the Hebrews is introduced in Exod. 1:8-13, and Moses suddenly appears in 2:11-23a. Whatever stories may have been included in the early strand of tradition are gone, and at a later time the story of Moses as the hero of the Exodus was expanded by a story of the miraculous deliverance of Moses from the hostility of Pharaoh as a child (just as J has him escape as an adult in 2:15), modeled after the story of Sargon of Agade. At the same time, it is possible from the outline below to see how the writer developed his theme from creation to the time when the Hebrews were about to enter Canaan. Almost every documentary analysis is in agreement on the bulk of what is to be included in the various collections, but each scholar finds some passages that do not fit the schema. J materials listed below represent generally accepted passages. Those marked with an asterisk are, according to personal analysis, probably not J. The parenthetical remarks, also marked with an asterisk, indicate where this writer believes they belong.”

Biblical Passages Attributed to J

Beginnings Gen. 2:4b-3:24: Creation myth.

Gen. 4:1-16: Why the blacksmith bears a trade-mark.

Gen. 4:17a: The birth of Enoch (the account of Cain as a city dweller in 4:17b contradicts 4:1-16 and hence represents a different tradition).

Gen. 4:18-26: The beginnings of nomadism (note 4:26b where the beginning of Yahwism is indicated in spite of Gen. 4:1-16).

Gen. 5:29: Noah is blessed for the gift of wine (cf. Gen. 9:18-27).

Gen. 6:1-4: The sons of God and the daughters of men.

The Noah Cycle Gen. 6:5-8: God's decision to destroy men by flood.

Gen. 7:1-5, 7-10, 12, 16b, 22-23; 8:2b-3a, 6-12,13b: Noah and the flood.

Gen. 8:20-22: Noah's offering.

Gen. 9:18-27: Noah's vineyard and drunkenness.

Gen. 10:8-19, 21, 24-30: The descendants of Noah.

The Diffusion of Tongues Gen. 11:1-9: The tower of Babel.

[Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,”1968, infidels.org ]

The Abram (Abraham)-Isaac Cycle Gen. 11:28-30: Remnants of the Abram (Abraham) genealogy.

Gen. 12:1-4a: The summons to leave home.

Gen. 12:6-9: Abram in Canaan.

Gen. 12:10-20: Abram and Sarai in Egypt.

Gen. 13:1-5, 6a, 7-11a, 12b-18: Abram and Lot.

Gen. 16:1-2, 4-8, 11-14: Abram's son Ishmael.

Gen. 18:1-16, 20-19:28: The destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah.

Gen. 19:30-38: The ancestry of Moab and Ammon.

Gen. 21:1-2a, 7: The birth of Isaac.

Gen. 21:33: Abraham at Beer-sheba.

Gen.22:15-18, 20-24: Renewal of promise to Abraham (15-18 appears to be a post-D redaction; 20-24 come from an unknown source).

Gen. 24:1-67: Isaac takes Rebekah as wife.

Gen. 25:1-6, 11b: Abraham's other children (because this account comes as an intrusion in the J account it is often treated as a late addition.

Gen. 26:1-3a, 6-33: Isaac and Rebekah in Gerar (note the repetition of the Abraham legends. Cf. Gen.26:1-5 and Gen. 12:1-4; Gen. 26:6-11 and Gen. 12:10-20).

Part of Genesis written mainly by J and P

The Jacob Cycle Gen. 25:21-26a: The birth of Esau and Jacob.

Gen. 25:27-34: Esau sells his birthright.

Gen. 27:1-45: By deception Jacob obtains Esau's blessing (two accounts are blended; the earliest is: 27:1-10, 17, 18a, 20, 24-27a, 29b-32, 35-39a, 40a, 41-45).

Gen. 28:10-22: Jacob at Bethel (The full account is probably an expansion of the J material).

Gen. 29:1-30: Jacob marries.

Gen. 29:31-35: The birth of Reuben, Simeon, Levi, and Judah.

Gen. 30:1-43: Jacob and Laban (conflation of J and E materials. Probably J=30:9-16, 22, 24b, 25, 27, 29-43).

Gen. 31:1, 3, 21a, 44, 46, 48 and parts of 51-53a: Jacob's flight. The covenant with Laban.

Gen. 32:3-12, 22: Jacob prepares to meet Esau.

Gen. 33:1-17: Jacob meets Esau.

Gen. 34:3, 5, 7, 11-13, 18, 19, 25-26, 30-31.: The defeat of Shechem.

Gen. 35:21-22a.: Reuben and Bilhah.

Gen. 38:1-30: Tamar and Judah.

The Joseph Cycle (overlaps Jacob Cycle) Gen. 30:22-24: The birth of Joseph (a conflation of J and E).

Gen. 37:3-36: Joseph and his brothers. (The original "J" material has been expanded. Probably J=Verses 3-4, 12-18, 21, 23, 25-27, 28b, 31-35).

Gen. 39:1-23: Joseph and Potiphar's wife.

Gen. 42: Joseph and his brothers. (An expanded J story. J=42:2, 5-7, 26-28, 38.)

Gen. 43: Joseph and the second visit of his brothers.

Gen. 44-45:4: Joseph reveals his true identity.

Gen. 45:9-14, 19, 21-24, 28; 46:28-34: Jacob comes to Joseph.

Gen. 47:1-26: Jacob settles in Egypt.

Gen. 47:29-31; 48:2b, 9b-10a, 13-14, 17-19: Jacob's blessing.

Gen. 49:1-27: Poetic form of blessing ( from an early non-J source).

Gen. 50:1-11,14: The death and burial of Jacob.

Exod. 1:6: The death of Joseph.

The Moses Cycle Exod. 1:8-12: The persecution of the Hebrews.

Exod. 2:11-23a: Moses' flight to Midian.

Exod. 3:2-4a, 5, 7-8a, 16, 18; 4:1-16, 19-20a, 22-23: Moses is told to save the Hebrews.

Exod. 4:24-26: Yahweh tries to kill Moses.

Exod. 4:29-31: Moses convinces the Hebrews.

Exod. 5:3, 5-23; 6:1: Moses and Pharoah (references to Aaron are redactional).

Exod. 7:14-15a, 16-17a, 18, 21a, 23-25: Nile waters are turned to blood.

Exod. 8:1-4, 8-15a: The swarm of frogs.

Exod. 8:20-32: The swarm of flies.

Exod. 9:1-7: The death of the cattle.

Exod. 9:13, 17-18, 23b-24, 25b-29a, 33-34: The hailstorm (9:14-16, 19-21, 29b-32 are redactions possibly added by the compiler of JE).

Exod. 10:1, 3-11, 13b, 14b-19: The plague of locusts (10:2 is a redaction).

Exod. 10:24-26, 28-29: Pharoah accedes to Moses' demands.

Exod. 11:4-8; 12:29-30: Death of Egyptian firstborn.

Exod. 12:21-27: Passover rite (late redaction).

Exod. 13:3-16: Firstfruits ritual (late redaction).

Exod. 13:21-22: Yahweh leads his people.

Exod. 14:5-7, 10-14: Pharoah's pursuit.

Exod. 14:19b-20, 24-25, 27b, 30-31: Yahweh saves his people.

Exod. 15:22-25, 27: Wilderness wanderings.

Exod. 16:4-5: Yahweh gives his people daily bread.

Exod. 17:1b-2, 7: The people thirst.

Exod. 19:2: At Sinai (2b may be E).

Exod. 19:3b-9: Covenant terms (a late redaction, probably Exilic).

Exod. 19:18, 20a, 21: Yahweh on Sinai.

Exod. 24:1-2, 9-11: The Covenant meal (a late redaction extending the idea of Exod. 18:12-E).

Exod. 32:9-14: Moses intercedes for the people.

Exod. 32:25-34: Punishment (verses 30-34 are the work of Rje).

Exod. 33:12-23: The glory of Yahweh.

Exod. 34:1-28: The tablets of law, including the "ritual decalogue" (possibly a D source reworked by Rp).

Num. 10:29-32**: Moses with Hobab (here Hobab is Moses' brother-in-law. Cf. Judg. 4:11).

Num. 10:35-6: The Song of the Ark (an old poem used by J).

Num. 11:4-15, 18-23, 31-35: Quails for food.

Num. 12:16; 13:17b-20, 22-24, 26b, 28, 30-32: Spying out Canaan.

Num. 14:1, 3-4, 11-12, 31-32, 39-45: The failure of the first attack.

Num. 16:1a, 12-15, 25-26, 27b-34: Revolt of Dathan and Abiram (J reworked in the spirit of D).

Num. 20:1b: Death of Miriam.

Num. 20:2a, 3: Lack of water.

Num. 21:1-3: The struggle at Hormah.

Num. 21:14-18, 27-30: Early poems probably preserved in J.

Num. 22:2-3a, 5-7, 17-18, 22-35a: Balaam and his ass.

Num. 24:3-9, 15-19: Balaams's oracles.

Num. 25:1-5: Israel yoked to Ba'al of Pe'or.

Num. 32:34-39, 41-42: J's summary of holdings of Ga, Reuben and Manasseh.

** The J material in Numbers is so interwoven with the material that was added to expand the account that it is impossible to separate J with any certainty. The material attributed to J must be accepted as conjectural.

J Saga

Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “Just when or how the J creation myth (Gen. 2:4b-3:24) originated is not known. Because scholars believe that various older myths can be traced within the story, it is not likely that the J writers invented the story. As it stands in its present form, the myth describes God in anthropomorphic terms planting a pleasure park, molding man from clay as a potter might do, and blowing into man's nostrils his own breath, animating the earth that was man so that man began to breathe. This creature was to be a gardener and was forbidden to eat of the tree of moral knowledge on threat of immediate death (2:16 f.). [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,”1968, infidels.org ]

“Perceiving the loneliness of man, Yahweh decided to create a helper and continued to mold creatures out of clay, bringing each in turn to the man. Man named each creature (thus J explains how creatures received their specific designations) but found none that was really suited to his needs. Then God caused man to sleep and extracted a rib (perhaps J's explanation of our "floating ribs") and modeled a new creation from this part of man. When man awoke and saw this new creature, he cried "At last! This is it!" (Perhaps J implies that this is the experience of every man who falls in love.) In man's recognition that woman is "bone of my bone" and "flesh of my flesh" and in the observation of Verse 24, J implies that man is incomplete until he finds the one who represents his missing part! J's delight in punning is apparent, for the new creature is called ishshah (woman) because she was taken from ish (man). Man, therefore, rejected the animal kingdom in favor of the creature made from himself-woman-and perhaps J intended to provoke a smile, for in this instance woman was "born" of man.

“At this point the serpent is introduced, a creature made to be a helper but rejected by man. Wiser or more cunning than the other creatures, the serpent scoffed at the prohibition pertaining to the tree of knowledge of good and evil, pointing out that eating the fruit would not bring death but would result in possession of knowledge restricted to divine beings. Thus tempted, the woman and man ate and, as the serpent had promised, found that they did not die but possessed moral knowledge. The new knowledge brought awareness of nudity and so men, unlike animals, require artificial clothing-first of leaves, then of animal skins. In guilty awareness of the violation of God's command, the couple attempted to hide. Yahweh, walking in the garden, could not find them and called them forth, and all three participants in the misdemeanor were punished. The sentences explain phenomena of life-why the serpent crawls upon its belly, why men kill snakes, why snakes bite men, why women experience pain in childbirth and yet continue to have children, why men toil so hard for a living, and why nature seems to thwart man's best efforts. Now, lest man should eat of the other tree-the tree of immortality-and become like a god, the man and his wife were expelled from the garden and prevented from re-entering by the guardian cherubim and the sword of lightening.

“The motifs within this story are very familiar. The mortality of man, the kinship of man and animal, the separation of man and animal, and the similarity of man to the gods except that man does not possess immortality are all themes within the Gilgamesh Epic. While other pre-Exilic Hebrew literature known to us ignores this story and while some scholars have argued that it should not be included within the J material, there is elsewhere in J (the Tower of Babel story) the theme of man seeking to enter the realm of the divine, and the Psalmists have picked up the theme of man's mortality and sub-divine status (compare Ps. 8:5; 49:20). Centuries later, Christian theologians interpreted the story in terms of man's "fall" from a pure state and although the story does tell of the expulsion of Adam from paradise (see Rom. 5), its central theme is the ascent of man through moral knowledge to a level of awareness akin to that possessed by the deity.

“The story of Cain and Abel, sons of Adam and Eve, is a legend relating to a specific group of people, revealing the author's belief that animal offerings (symbolic of the herdsman) are superior to agricultural offerings (symbolic of the farmer). The account is aetiological, explaining why the roving blacksmiths (one meaning of the name Cain is "smith") are able to roam from place to place with no strong tribe to guarantee safety and, possibly, explaining how a peculiar mark, which may have been the symbol of the smith's trade, came into being. In its present setting the story forms part of the pattern of deepening evil that culminated in the flood. In a sense, Cain and Abel are "everyman"-brothers separated by jealousy and misunderstanding that leads to violence. J indicates that man having acquired moral knowledge had not achieved moral responsibility.

“Of the stories pertaining to human beginnings, perhaps that telling of the intermarriage of divine beings and "the daughters of men" is most perplexing. Divine-human marriages were common in the mythologies of the Near East and quite often the children were mighty warriors, so perhaps J was drawing on one of these themes. Perhaps he saw in the story another example of man's arrogance and an attempt to achieve divinity; but God limited human life to a maximum of 120 years. It is also possible that J is attacking Canaanite cult prostitution in which the hierodules, both male and female, played the role of the deities who met with worshipers in sacred copulation rites. J notes that such relationships were the prelude to the flood. In any case, we have only a truncated myth, and J's purpose in recounting it is not clear.”

Mesopotamia and the Noah Cycle and Tower of Babel

Tower of Babel

Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “The source of the flood story can be traced to Mesopotamia and the eleventh tablet of the Gilgamesh Epic, which in turn rests upon an older Sumerian flood legend. It is unlikely that such a story would develop within Palestine where the Jordan flows below sea level. The obvious marks of literary borrowing and the discovery of a fragment of the Gilgamesh Epic at Megiddo from the fourteenth-century level suggests that the story was known in Canaan prior to the Hebrew invasion, and would have come into the J material from Canaanite sources. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,”1968, infidels.org ]

“Certain noteworthy differences between the Mesopotamian versions and the J account can be discerned. When the Hebrews borrowed the story, they related it to their own deity, Yahweh, discarding the polytheistic pattern of the Gilgamesh account. Furthermore, the flood in the Hebrew story came as a judgment resulting from Yahweh's regret that he had made man because of the latter's continued evil action, while in Gilgamesh mankind was to be destroyed by vote of the gods with no real reason provided.16 Finally, the hero of the Gilgamesh flood story, Utnapishtim, is rewarded with immortality for himself and his wife, while Noah and his family die as all mortals must. What the Hebrew writers borrowed they transformed in the light of their own theological convictions.

“During the excavation of ancient Ur and nearby Al 'Ubaid, Sir Leonard Woolley uncovered evidence of what he interpreted as a major flood which occurred in the middle of the fourth millennium, and which covered an existing culture with a deposit of sediment to depths varying from eight to eleven feet. Similar deposits were found in other Mesopotamian sites, but these were from different periods. It has been argued that the Mesopotamian and biblical flood traditions may have their origin in a flood of unprecedented proportions. Woolley's interpretation of the evidence has been challenged and there are those who argue that what Woolley and others interpreted as river sediment is, in fact, a great layer of sand deposited by the dreaded idyah, a dust storm which occurs in the spring and summer in Mesopotamia, and which may lay down a thick layer of sand particles to form what is known as an "aeolian formation." The aeolian formation is quite different from river sediment. But this re-interpretation cannot be accepted as final, as the rebuttal from supporters of the Woolley hypothesis has demonstrated. We can only conclude that Mesopotamian floods did occur, that there is ample literary evidence of the disaster they brought to some settled areas and that it is quite possible that the flood traditions rest in an actual experience or series of experiences of the destruction wrought by these high waters.

“The tower of Babel story can be related to the ziggurats or temple towers of Mesopotamia. These huge, man-made mountains of sun-dried brick, faced with kiln-baked brick often in beautiful enamels, rose several hundred feet above the flat plains of Mesopotamia. Used in the worship of the various deities to whom they were consecrated, they seemed to J a fitting symbol of man's arrogant pride. Selecting the ziggurat at Babylon dedicated to Bel-Marduk, J describes the great building project as an attempt of man to invade heaven, which, in Near Eastern thought, was believed to be just above the zenith of the firmament. To thwart human ambitions, Yahweh caused men to speak in different languages, and because men who cannot speak together cannot work together, the project failed. This, J explained, was why mankind, descended from a common ancestor, Noah, spoke different languages. Once again J's delight in puns is demonstrated for God confused ( balel) man's speech at Babel, or as Dr. Moffatt's translation aptly puts it, the place "was called Babylonia" for there God "made a babble of the languages."

Abraham Cycle According to J

Larue wrote: “The patriarchal narratives begin with the story of Abraham and tell of a promise made by Yahweh that a great nation would come from Abraham's offspring (which J believed was fulfilled in his time). Placed as it is, following three failures of man to fulfill divine expectations (Adam, Noah, Babel), the Abrahamic cycle represents a new beginning, a new creation by Yahweh, centered not in mankind in general but in one individual who responds to a divine call and through whom mankind in general may receive blessing. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,”1968, infidels.org ]

“The thrust of the story, as indicated by its location, is in the concept of election, the special choice by Yahweh of a man, and hence a people, through whom the divine intention might be realized. It is possible that the remnant motif, which plays a large role in later thought, finds its beginning here, for it is in the faithful one that Yahweh puts his trust and builds for the future.18 Where the Abraham tradition originated is not known, but most likely it came from tribal families among the Hebrews with a tradition of Mesopotamian origins. The two names for the patriarch, Abram and Abraham, may reflect separate cycles. The identification of the two names is preserved in a late priestly tradition (See Gen. 17:5).

“Like other Hebrew heroes, Abraham went to Egypt19 and returned, rich in material wealth, to spend some time in the Negeb (Gen. 13:1-2). If there is any remnant of historical truth within this account, the Negeb journeys would seem to fit best into the period between the twenty-first and nineteenth centuries, a period during which, according to the great explorer and archaeologist Dr. Nelson Glueck, numerous settlements dotted the Negeb. Moving northward into Palestine, the families of Abraham and Lot separated. Lot went to Sodom to become the paternal ancestor of the Ammonites and Edomites. Abraham, after being promised the area subsequently occupied by the Davidic-Solomonic kingdoms, settled at Hebron where he is said to have founded the shrine (Gen. 13:18). Abraham became the patriarchal ancestor of the Ishmaelites, of Isaac and the tribes descended from him, and of various other unknown tribal groups.

J, Isaac and Jacob

Isaac Blesses Jacob

Larue wrote: “The Isaac stories repeat many of the motifs found in the Abrahamic cycle, so it would appear that the J writer had cycles of very similar material pertaining to the patriarchs, and he combined them by making one figure the ancestor of the other. The election motif is touched with the element of the miraculous, for when Abraham's hope for posterity has faded, Isaac is born. Isaac became the paternal ancestor of the Edomites (Esau) and the Israelites (Jacob), and from Jacob came the majority of the tribes forming the Hebrew nation. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,”1968, infidels.org ]

“The familiar motif of an old woman bearing offspring after many years of barrenness through the gracious intervention of Yahweh appears again, this time associated with Rebekah (compare Sarah: Gen. 11:30; 16:1; Rachel: Gen. 29:31; 30:22). Rivalry between Edom and Israel, symbolized by the twins Esau and Jacob, began in the womb and the results of that struggle were predetermined by Yahweh. Like Ishmael, the first-born of Abraham, Esau, the first-born of Isaac, did not enjoy the preferential status usually associated with primogeniture (see Gen. 43:33), and this loss of stature is explained by Esau's sale of his birthright, an action that parallels an incident recorded in Nuzi texts. J does not condemn Jacob's deception of Isaac to obtain Esau's blessing, possibly because what took place was actually in accord with Yahweh's prediction and was, therefore, a fulfillment of Yahweh's will. On the other hand, there is little condemnation of trickery in J, for it was assumed that a clever person would resort to such tactics.

“J's literary artistry is clearly demonstrated in depicting the rugged, hungry hunter selling his birthright for a bowl of lentils; in the picture of the bewildered, blind father seeking to assuage Esau's bitter disappointment with a second blessing; and in the interplay of characters: father, mother and sons. His delight in the play on words appears when Jacob ( Ya'akob) grabs his brother's heel ( 'akeb). The differences between the two boys, foreshadowing distinctive way of life for their descendants, is emphasized by the separateness of their habits, interests, food, attitudes and associations. Esau is the hunter, the man of the steppes; Jacob symbolizes the established farmer or herdsman, the businessman, the man given to the settled life.

“Jacob's Bethel vision is undoubtedly linked to the concept of the Mesopotamian ziggurat with its stairway between heaven and earth. Even Jacob's assertion that this was the "gate of heaven" is reminiscent of the name Babylon ( Bab-ilu, "gate of gods"), a city with a great ziggurat. The story links Jacob with the important cult center at Bethel and provides an aetiological basis for the massebah that must have stood there. Archaeological research has disclosed that the city was standing during the Middle Bronze period, and it is possible that the name "Bethel" ("House of El") symbolizes its importance as a Canaanite sanctuary. Cult legends associating the place with the patriarchs sanctified it as a Yahweh shrine, which it was to become. What is most significant in the episode is the divine assurance of fulfillment of the election promise given to Abraham, by which J clearly keeps before the reader the line of succession for the chosen people.

“Haran again becomes the center of patriarchal action in the marriage sequence when Jacob is bested by his uncle Laban. Once again J's literary skill is revealed. The communal watering hole which could not be utilized until all owners were present, was opened by a young man determined to prove himself before an attractive young woman. The substitution of Leah, the older and presumably the less comely daughter, for Rachel on the wedding night, becomes a test of Jacob's love for Rachel and, ironically enough, provides the offspring from which came the tribal groups that produced the great Hebrew leaders Moses and David. Jacob's methods of increasing his flocks rested on beliefs in magic. Finally, financially secure, he left Laban to return to his homeland where, despite his fears, he was warmly welcomed by Esau.

“The story of Judah and Tamar, which has no particular relationship to the Jacob cycle, preserves an independent tradition of the way in which the Judah tribe was saved from extinction by a wily widow. The responsibility for continuing the line of a married man who died without offspring rested with the next of kin, according to a custom known as "levirate" (husband's brother) marriage (cf. Deut. 25:5 ff.). The Joseph traditions reflect dependency upon older Egyptian stories. The story of Potiphar's wife is like the Egyptian "Tale of the Two Brothers," and the account of the seven lean years may be related to the "Tradition of the Seven Lean Years in Egypt" found in the Egyptian sources.”

J and the Moses Cycle

Michelangelo's Moses

Larue wrote: “The election motif is continued in the Moses cycle but, with the deliverance of the Hebrews from Egypt, it takes on the new emphasis of salvation-history, a theological interpretation greatly expanded by later writers. The real character of Moses cannot be ascertained from J or from the expansion of his story by subsequent editors. All that remains is an interpretation of this great leader by those who wrote long after Moses had died. The participation in building Pithom and Raamses may rest upon sound historical memory. Pictures of slaves, including Syrians, making bricks have been found in the fifteenth-century tomb painting depicting the building of the temple of Amun at Karnak (cf. Exod. 5:6 ff.). [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,”1968, infidels.org ]

“Moses is introduced as an adult, a murderer compelled to flee because his act was witnessed by a Hebrew. The sneering rebuke of the witness may reflect a lost J tradition of Moses' involvement with the royal family of Egypt or may simply imply that Moses was setting himself above others. The flight to the desert brought Moses into the family of Reuel, the Midianite. At the burning bush (note the absence of any mention of the sacred mountain), Moses was summoned by Yahweh to deliver the people from Egypt. The strange record of Yahweh's attempt to kill Moses and the rescue by the action of Zipporah, Moses' Midianite wife, is related to the origin of the rite of circumcision, possibly suggesting that Israel learned the custom from the Midianites.25 The reluctant pharaoh, finally persuaded by dramatic acts, released the Hebrews. Passages making a definite link between the Exodus and Passover and Firstfruits are often associated with the J source but may also be treated as later additions.

“Yahweh's presence with the fleeing Hebrews was symbolized by pillars of cloud and fire. Just how the pursuing Egyptians were halted is not clear, except that their chariots became mired in the sea. After wandering in the wilderness, the complaining people reached Mount Sinai where, according to tradition, covenant terms and law were given. The account concludes with the abortive attempts to enter Palestine and the apostasy of the people.”

P: The Final Major Contributor to Early Old Testament

Larue wrote: “During the Persian period toward the close of the fifth and the beginning of the fourth centuries, the last major contribution was made to the Pentateuch. It has already been noted that the accumulation of priestly lore had been taking place in Babylon during the Exile. Now this process came to an end and the results were woven into the previously combined JE saga and into Deuteronomy. In its final form, P gives an impression of homogeneity and, to some degree, appears to be a narrative paralleling JE. On the other hand, as we also noted earlier, in certain instances P seems to be no more than a series of small additions to the JE story which give the completed narrative an entirely new emphasis or coloration. In P, the process of progressive or continuing interpretation can be seen. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

“It is occasionally said that P is what remains when J, E and D are removed from the Torah, but the P editor had his own distinctive style, and the completed Torah reveals the fruits of his carefully worked out systematization and theological interpretation of the past. Broadly speaking, P can be distinguished from the other sources of the Pentateuch by an easily recognized characteristic language, literary style and theological outlook. Like J, P refers to the holy mountain as "Sinai," and, as in E, the name Yahweh is avoided until it is revealed to Moses. There is a strong emphasis on the gathered people of Israel as a "congregation" (see Leviticus). P avoids the covenant terminology of JE and D ("to cut a covenant") because the language was employed for both secular and divine agreements. In P, Yahweh "establishes" (Gen. 6:18; 9:9, 11; 17:7, etc.) or "grants" (Gen. 9:12; 17:2, etc.) covenants.

“P's style tends to be stiff and stilted in contrast with the flowing narrative form of J and E. As in D, once a phrase has been accepted it is used over and over again. This characteristic may be seen in the creation account in Gen. 1 in the repetitive use of "and God said," "and it was so," "and there was evening and there was morning," "and God saw that it was good." At the same time the repetition conveys to the listener or reader a sense of order, balance, dignity and weight, quite appropriate to the content. It is conceivable that the formal style of P reflects cultic settings and liturgical usage, where mnemonic devices and schematic arrangements might be expected, and where repetition served to reinforce the significance of traditional language. Genealogical tables are usually introduced by the stereotyped phrase "these are the generations of," but, as we shall see, these tables do more than give the priestly material a sense of orderly development; they are carefully designed to carry the reader from the universal to the particular, from mankind in general to Israel in particular. The schematic, formalistic presentation, the noting of minute details and the recurring use of literary formulae that can be discerned readily in English translation aid the reader in separating the P source.

“Insofar as possible, P moved away from depicting Yahweh anthropomorphically. There are notable exceptions: man is made in God's image (Gen. 1:26 f.; 5:1; 9:6) and after the six days of creation God rested (Gen. 2:2) and was refreshed (Exod. 31:17). P's emphasis is on the transcendence of God, and he stresses the distance between God and man and between the sacred and profane. Yahweh's revelation is through his glory ( kabod) as in Ezekiel, but the kabod is veiled in a cloud (Exod. 24:15 ff.).

Other theophanies or manifestations are drawn with minimal descriptions (Gen. 17:1 ff.; 35:9 ff.; Exod. 6:2 ff.). The transcendent deity is approached through the mediation of cultic ritual and cult functionaries. Cultic patterns are prominent, and even narrative portions relate to the cultus: the creation story leads to the establishment of the Sabbath (Gen. 2:2 f.), the flood account to the prohibition of eating flesh with its blood (Gen. 9:4), and the Abrahamic covenant to circumcision (Gen. 17:10 ff.). Clear-cut rules for sacrifice, for distinction between clean and unclean food and for festal observances, underscore the importance of the cult in maintaining the binding relationship between God and man. Consequently, the priests come into prominence as mediators. In the idealized portrayal of the desert period, the tent sanctuary of Yahweh is walled off from the people by priests and Levites who symbolically stand between God and the people (Num. 2). Yahweh speaks to Moses and Aaron, not to the people, and after the demise of these two heroes of the faith there is no further direct communication. Throughout P there is no hint of the reality of other gods, for between the final editing of P and the other contributions to the Torah were the experience of the Exile and the teachings of Deutero-Isaiah. No altar is recognized but that in Jerusalem. The image of the nation is that of a community of worshipers linked to Yahweh through the cult, its institutions and the clergy.

Literary and Historical Clues in P

Larue wrote: “Within P there are clues that indicate that the final product was the result of editing and selection, perhaps done by one person. There are passages in disagreement, interruptions in continuity and isolated blocks of material. Num. 4:23 ff. states that the age for Levites to begin temple service is thirty years, but Num. 8:24 says twenty-five years. Aaron, as high priest, and only those of his descendants who succeeded him in office are anointed in Exod. 29:7, 29, and Lev. 4:3, 5, 16, recognizes only one anointed priest; but according to Exod. 28:41 and 30:30, Aaron and his sons are anointed implying that all Aaronic priests and not just the high priest were anointed. It would appear that traditions with slight differences were combined. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

“Distinct units of literature may be recognized within the opening chapters of Leviticus. The first seven chapters deal with sacrifice; Chapters 8 to 10 suddenly turn to the rituals at Sinai; Chapters 11 to 15 consider problems of cultic cleanliness and uncleanliness. The links between these units are weak, and it can be readily seen that small collections of priestly instructions have been combined;12 there is also evidence of even smaller units within the collections. There have been some attempts to trace threads of sources running through P, but these efforts are far too detailed for discussion here and would not be particularly rewarding.13

“Scholars usually place the time of the compilation of P in the post-Exilic period14 for a number of reasons. In the writings of II Isaiah, Haggai, Zechariah and Malachi there is no presupposition of the teachings found in P. J and E knew of many cult places, and D sought the elimination of all but that in Jerusalem, but P assumes that the only cult center was at Jerusalem, and is, therefore, at the end of this line of development. On the other hand, some parts of P appear to be pre-Exilic. Certain cultic terms are the same as those found in the temple literature of Ugarit (twelfth to fourteenth centuries), and some of the ceremonial regulations may be drawn from pre-Exilic ritual. Therefore, P contains both pre-Exilic and post-Exilic literature which, merged with JED, constituted a reinterpretation of these previously combined writings.

“The identity of the final editor or compiler is not known, but it can be assumed that he was a priest. Ezra has been put forth as a possible candidate, and it is suggested that P was the law that Ezra interpreted and imposed on the people. Unfortunately, these hypotheses cannot be confirmed.”

Structure of P

Larue wrote: “P gives the Pentateuch its chronological framework. Simply stated, the structure of P consists of a development from the general to the particular, from man in general to the chosen of Yahweh in particular, from Yahweh the creator of the world to Yahweh the God of the Jews. The theme may be diagrammed in a number of ways. In the first sketch, God's narrowing interest is portrayed, beginning with the created heavens and earth, then moving to man (generic), narrowing to Noah and his son Shem (the father of Semites) and to a single family leading to Abraham. Finally, single sons are chosen, and ultimately Jacob, who becomes Israel. Within the family of Israel, Moses and Aaron are singled out as the greatest individuals. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

“Another chart can be constructed from the genealogical tables.15 Starting with Gen. 5 and the descendants of Adam, the first man, the line is traced through Seth to Noah. Noah's descendants are listed in Gen. 6:9-10 and Gen. 10. From Shem, the line is traced to Abram (Gen. 11:10 ff.) and with Abram a break with the locale of the past takes place and the lineage becomes Palestinian-centered. The chosen people do not descend from Ishmael, Abram's first-born by the Egyptian maid Hagar (Gen. 16:3, 15-16; 25:12 ff.), but from Isaac (Gen. 21:3-5; 25:19 ff.), and not from Esau, Isaac's firstborn (Gen. 36), but from Jacob (Gen. 35:22b-29). The rejection of the first-born can only be explained as God's free choice (election).

“A third diagram, expressing the deepening relationship between Yahweh and his creatures, and beginning with mankind in general and ending with the Hebrews, centers in covenantal relationships. Having created mankind, God decreed that man should have plants for food and should exercise dominion over the animals. When man failed in his responsibilities, God began the human family anew in the chosen line of Noah and made a covenant promising that the new human line would never again perish by floods (Gen. 9:8ff.). In Abraham, God narrowed his choice and made a new covenant embracing only the Abrahamic family and promising nationhood. The Mosaic covenant included only the descendants of Jacob and bound the twelve tribes to Yahweh. At Sinai the most important revelation was given, for here was given the cultic legislation that provided the continual link of the chosen people with Yahweh. The creation decree and the Noachic covenant are general, affecting all mankind. The Abrahamic and Mosaic covenants are particularistic.

“The different divine names used by P signify a development in divine revelation. At first, P used the general designation "Elohim" for the deity. With Abraham, the name "El Shaddai" is introduced and used along with Elohim. The revelation of the personal name "Yahweh" at Sinai was reserved for the chosen people. The use of divine names by P, once again, provided the Jews with a sense of the uniqueness of their divine-human relationships. The recognition of P's schematic arrangement of the Torah traditions reveals P's understanding of Yahweh's historic relationship to his people. In the final revelation given at Sinai, the significance of the cult in maintaining the binding covenant and in expressing the meaning of election is portrayed.

Biblical Passages Attributed to P

From Creation to Noah Gen. 1:1-2:4a: Creation in seven days.

Gen. 5:1-28, 30-32: Genealogical table from Adam to Noah.

The Noah Cycle Gen. 6:9-22; 7:6, 11, 13-16a, 17-21, 24; 8:1-2a, 3b-5, 13a, 14-19: Noah and the flood.

Gen 9:1-17: The Noachic covenant (the rainbow).

Gen 9:28-29: The death of Noah.

Gen 10:1-7, 20, 22-23, 31-32: Genealogy of the sons of Noah.

The Abraham Cycle Gen 11:10-27, 31-32: Genealogy from Shem to Abram.

Gen 12:4b-6: Abram goes to Shechem.

Gen 13:6a, 11b, 12a: Editorial expansions.

Gen 16:3, 15-16: The birth of Ishmael.

Gen 17:1-27: The Abrahamic covenant (circumcision).

Gen 19:29: The rescue of Lot.

The Isaac Cycle Gen 21:1b, 2b-6: The birth of Isaac.

Gen 23:1-20: The death and burial of Sarah.

Gen 25:7-1la: The death and burial of Abraham.

[Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

Gen 25:12-18: The Ishmaelites.

Gen 25:19-20, 26b: Isaac's descendants.

Gen 35:27-29: The death of Isaac.

The Jacob Cycle Gen 27:46-28:9: A wife for Jacob.

Gen 31:18: Jacob leaves Laban.

Gen 34:1-2, 4, 6, 8-10, 14-17, 20-24, 27-29: The rape of Dinah.

Gen 35:9-15: Jacob at Bethel.

Gen. 35:22b-26: The sons of Jacob.

Gen. 49:28-33: The death of Jacob.

Gen. 50:12-13: The burial of Jacob.

The Esau Cycle Gen. 26:34-35: The wives of Esau.

Gen. 36: The Esau genealogy.

The Joseph Cycle Gen. 37:1-2: The identity of Joseph.

Gen. 46:6-27; 47:27-28: Israel in Egypt.

Gen. 48:3-6: The promise to Joseph.

The Moses Cycle Exod. 1:1-5, 7, 13, f.; 2:23b-25: Israel in Egypt.

Exod. 6:2-13: The revelation of the divine name.

Exod. 6:14-25: Genealogical table.

Exod. 6:26-7:13, 19-20a, 21b-22; 8:5-7, 15b-19; 9:8-12, 35b; 11:9-10: Moses, Aaron and Pharaoh.

Exod. 12:1-20, 28, 43-51: The institution of the Passover.

Exod. 13:1-2: The law of the firstborn.

Exod. 13:20; 14:1-4, 8-9: Pursuit in the wilderness.

Exod. 24:3-8, 15-18a: The covenant ritual.

Exod. 25: The ark of testimony.

Exod. 26: The tabernacle.

Exod. 27: The altar.

Exod. 28-29: The priesthood.

Exod. 30-31:18a: The incense altar and other furnishings.

Exod. 34:29-35: Moses descends from Mt. Sinai.

Exod. 35-40: The building of cultic items.

Lev 1:1-7:38: Rules governing making of offerings.

Lev 8:1-36: The ordination of Aaronic priests.

Lev 9:1-24: Aaron as high priest.

Lev 10:1-3: The sin of Nadab and Abihu.

Lev 10:4-11:47: Separation of clean and unclean.

Lev 12: Laws of cleanliness pertaining to women.

Lev 13-15: Laws of health and ritual cleanliness.

Lev 16: The scapegoat and the atonement ritual.

Lev 17-26: The "Holiness Code."

Lev 27: Rules concerning vows and tithes.

Num 1-4: Census taking.

Num 5: Testing by the waters of bitterness.

Num 6: Regulations covering the Nazirite.

Num 7: Offerings at the tabernacle.

Num 9: The purification of Levites.

Num 8: Rules for Passover.

Num 10:1-28, 33-34: The departure from Sinai.

Num 13:1-17a, 21, 25-26a, 27: Spying out Canaan.

Num 14:2, 5-10, 33-38: The forty-year sentence.

Num 15: Laws concerning offerings.

Num 16:2b-11, 16-24, 35-50: Korah's rebellion.

Num 17-18: Aaronic and Levitical priests.

Num 19: Purification rituals.

Num 20:22-29: The death of Aaron.

Num 21:10-13, 19-20, 31-32; 22:1: Israel in Moab.

Num 25:6-18: Thwarting of intermarriage with Midianites.

Num 26: Moses takes a census.

Num 27:1-11: Inheritance laws.

Num 27:12-23: Joshua is commissioned.

Num 28-29: Festal offerings.

Num 30: Rules governing vows.

Num 31: Vengeance on Midian.

Num 32:6-15, 18-19, 28-33: The settling of Reuben and Gad.

Num 33: Recapitulation of Israel's journey.

Num 34: The boundaries of the promised land.

Num 35: Cities of refuge.

Num 36: Inheritance rules.

Deut. 32:48-52; 34:la, 7-9: Moses on Mount Nebo.

Differences Between P and J

Larue wrote: “The priestly creation myth presupposes a pre-existent watery chaos out of which the cosmos was formed,16 and thus from its opening reveals an affinity with the Babylonian Enuma elish. The order of creation parallels that of the Babylonian myth: the firmament, dry land, the luminaries and man.17 In the Babylonian account, the gods rest and celebrate at the conclusion of their work, and in P, God rests and sanctifies the Sabbath. Although it is not possible to prove direct borrowing from the Babylonian myth by the Jewish writer, there can be no denying the close relationship between the accounts. Since Hebrew ancestry is traced to Mesopotamia through the patriarchs and as we have noted, the Babylonian Exile left deep imprints on Jewish thought, it is relatively easy to understand the common interpretation of the nature of the cosmos and to postulate a common source for the stories. It is usually conceded that the P account probably existed in the pre-Exilic period, although this idea is open to debate. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

“The differences between the P myth and the Enuma elish are as marked as the similarities, demonstrating a different handling of the basic material because of different theological convictions. The P account is monotheistic (despite the plural possessive form of 1:2618, which may be addressed to the "court of heaven") and lacks the patterns of divine strife and social upheaval of the Babylonian myth. In P, God creates by fiat without battle,19 although the term "created" in 1:1 (Heb: bara') may be interpreted as implying "fashioning by cutting" and thus reflect the same division of the basic stuff of the cosmos as Marduk's splitting of Tiamat, and the Hebrew word for "deep," tehom, in 1:2 has affinities with Tiamat, the Babylonian symbol of chaos. The Jewish story is climaxed with the creation of the Sabbath (the final verse, 2:4a, should probably be placed at the beginning of the account).

“There are striking differences between the J and P accounts in the order of creation, and these can readily be seen in the following chart:

P — J

light — heaven and earth

earth and seas — man

vegetation — a garden

luminaries fish and birds — animals and birds

land animals — woman

man and woman — the Sabbath

“The primeval harmonious relationship between primordial man and animals found in J and in the Babylonian story of Gilgamesh20 is reflected in P. The first man does not eat animals, but has a diet restricted to vegetable products (1:29), and only after the flood is man permitted to eat animal flesh (Gen. 9). The cosmology of P was discussed earlier. The shell of the firmament (a hard substance) holds back the cosmic waters that would ordinarily flood the space between earth and sky. The lack of critical analysis of natural phenomena enabled the writer to envision day and night existing before the creation of the sun, moon and stars. Eight creative acts take place in six days. The pattern of "days" probably does not reflect great time periods, but perhaps refers to specific days during the New Year Festival on which symbolic rites were performed, just as in the Babylonian Akitu festival.”

Noah and Abraham in P

Noah

Larue wrote: “Ten heroes span the period between the creation and the flood (Gen. 5). Much of the P contribution to the already existing J story of the flood consists of small details pertaining to the structure of the ark, the age of Noah and similar minutiae. Other additions are more significant. For P, the flood comes as a punishment for wickedness, and Noah's role is clarified as the remnant in which hope is placed for the future. The emergence of land after the flood waters cease mirrors P's creation story, for, as in Gen. 1:2, the movement of the "spirit" or "wind" (Heb: ru'ah) causes the waters to subside and the earth to reappear (8:1) for the new beginning of the story of mankind. With the new start came new decrees to all living creatures to multiply (8:14-16), and to Noah, as a symbol of the new man, to include animal flesh in his diet. The relationship between man and animal that enabled them to live harmoniously in the microcosm of the ark was past. The Noachic covenant guaranteed that the earth would never again be covered by flood waters, and the symbol of that covenant, the rainbow, served two purposes: as a sign of the covenant for man, and as a reminder to God of his promise. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

Most of P's contributions to the Abrahamic cycle are minor, but Chapter 17 is very important. God's relationship to Abraham is now set in covenantal form with the sign of the covenant being circumcision. Failure to be circumcised excluded the Jew from the holy community, and even Abraham, at the age of 99, was circumcised. At the opening of the Isaac cycle, P noted that Abraham circumcised Isaac when the child was eight days old, in conformity with the Abrahamic covenant (17:9 ff., cf. 21:4). Details were added about Sarah's death and burial (Gen. 23). The conversation with the Hittites may accurately reflect polite forms of speech utilized in business transactions. P added extra details about the death and burial of Abraham.

P explained that Jacob's visit to Laban was to acquire a wife and to keep the family line clear of foreign ties, and was not, as J had suggested, to escape from Esau (cf. Gen. 27:43-45). Esau, in an effort to please his parents, also chose a wife among his kin-folk, from the Ishmaelitic line (28:8 f.). New details and genealogies were added to the Jacob account, and new information revealed about the burials in the cave purchased by Abraham was attached to the Joseph traditions (49:28-33; 50:12-13).”

Moses, Leviticus and P

Larue wrote: “P had a separate tradition of the revelation of the divine name to Moses and, as we have noted, introduces a new dispensation with this revelation. The patriarchal covenantal promise was about to be realized and the new covenant that would govern future relationships about to be given. Aaron, as the prototype of the high priest, is depicted as the interpreter of Moses and the agent of God (Exod. 6:28-7:1, 8-13). The tradition of the plagues is heightened, ritual acts are described and new details are provided for historical-cultic observance of the Passover (Exod. 12:1-20, 43-49). [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org ]

“The covenant ceremony (Exod. 24:3-8, 15-18) adds ritualistic details and blood sacrifice to the rather simple J ceremony and no doubt reflects some aspects of the annual covenantal recital observed in the temple. Following the covenant rituals, cultic ceremonies and equipment are discussed, and since for P the cult is the means of maintaining the relationship between Yahweh and his people, details of rites, costumes and accessories are provided by Yahweh. Each item utilized in temple ritual is given a divine origin. The tabernacle or tent of meeting, which in P becomes a fully developed sanctuary, is made of materials more easily obtained in a developed, settled society than in a wilderness setting. When the ark of the covenant was built (and P's description indicates that it is a most ornate structure), the tablets of law were placed within it and the ark was set within the completed tabernacle in a spot corresponding to its location in the Solomonic temple. The primitive tent-sanctuary became, in P, an elaborate portable temple, the idealized magnificence of which was drawn from aspects of the completed temple. To imagine the Hebrews carting a structure of this magnitude and complexity about the desert staggers the imagination. The details concerning the priests, priestly apparel and priestly responsibilities do not suggest a wilderness setting either. Indeed, it is possible that in the case of the high priest the various costumes result from a combination of older literary sources in P so that articles of dress come from different historical periods.

“The expansion of cultic and liturgical themes in the book of Leviticus is far too detailed for consideration here, but the analysis of the contents listed above suggests the main themes. In the midst of the discussion of the clean and unclean in the Holiness Code, one of the most significant statements of human relationship in the Bible is found: "You shall love your neighbor as yourself" (Lev. 19:18). Although the major thrust of P's writings is God-man relationships in a cultic setting, rules for human conduct punctuate the liturgical concerns or are related to ritual (cf. Lev. 6:1-7; 19:9-18).

Moses and Aaron before the Pharaoh

“One of the central cleansing rituals is that for the Day of Atonement which provided for Aaron's (the high priest's) annual entry into the debir, the holy of holies of the tabernacle or temple. Rites of cleansing for the high priest and the priesthood prepared Aaron, followed by atonement rituals for the temple or tabernacle. Finally, the nation's sins were purged. The first ritual required the sacrifice of a bullock, which prepared the priest for entry into the presence of the deity. In the second rite, one of two goats chosen by lot was killed, and in the third the sins of the nation were confessed over the second goat and the sin-burdened animal taken into the wilderness to be destroyed, sins and all, by Azazel, presumably a wasteland demon. The high priest then reentered the hekal or holy place to bathe and change clothing before returning to the altar in the courtyard to offer sacrifice. It is generally believed that the ritual is post-Exilic, for it is not mentioned in pre-Exilic literature, and the impact of the Akitu festival can be recognized in the expulsion of the sin-bearer, here a goat rather than a man. The significance of the rite in providing a complete purging of sin for the nation and permitting an annual new beginning is not to be underestimated. In its present location, it forms a fitting prelude to the Holiness Code, which we have discussed earlier.

“Details of camp organization are set forth by P (Num. chs. 2-3). The tabernacle is at the center and is surrounded by orders of Levites. The twelve tribes form a protective ring, with Judah in the favored position on the east, the side of the rising sun. Other regulations, including those for testing the virtue of a wife by a jealous husband, and those for persons who become Nazirites, follow (Num. 5-6). Some regulations extend information previously provided (Num. 8, cf. Lev. 8). Provisions are made for a supplementary Passover to accommodate those defiled at the time of the regular observance (Num. 9). Ultimately, the Hebrews left Sinai and prepared for the invasion of Canaan, only to be sentenced to a forty-year desert sojourn because of lack of faith (Num. 14:26-38).

“The seriousness of observing ritual law is exemplified in the story of the Sabbath-breaker (Num. 15:32-36), and perhaps also in the Korah tradition (Num. 16). Events leading to the arrival at the border of the promised land are sprinkled with further legislation strengthening the role of the Levites, guarding the sanctity of the theocracy envisioned by P, or governing human rights and relationships.”

E: What’s Left When P, D and J are Removed

Larue wrote: “Broadly speaking, E can be said to include the literature which remains in the Pentateuch after P and D (easily identified) and J sources are removed, although in numerous passages it is difficult to distinguish between J and E. Distinctiveness of grammar, style and vocabulary, not always apparent in English translations, provide the basis for the identification of E material. Some of the more obvious features include labeling the sacred mountain Horeb rather than Sinai as in J, the identification of pre-Hebrew inhabitants of Palestine as Amorites, not Canaanites as in J, and naming Moses' father-in-law Jethro rather than Reuel. As we noted, E does not use the name "Yahweh" for the deity until it is revealed on Mount Horeb (Exod. 3:15). [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,”1968, infidels.org ]

“Because of E's fragmentary nature, it is impossible to make more than the most general comments about the writer's moral and theological concerns. At times E appears to exhibit greater concern than J with the moral implications of traditions, so that when Abraham pretends that Sarah is his sister, E points out that she was, in reality, a half-sister (Gen. 20). E makes it clear that Sarah did not cohabit with Abimelech. On the other hand, E seems untroubled by Aaron's lie. (When challenged by Moses in the golden calf episode, Aaron implied that the molten metal just happened to flow into the calf pattern, whereas the E editor has stipulated that Aaron fashioned the statue; cf. Exod. 32:4 and 24.) Some cruder anthropomorphisms of J are avoided in E and God's will is revealed through dreams (Gen. 15:1; 20:3; 28:12) or messengers (Gen. 21:17; 22:11), but E does not hesitate to state that God wrote laws with his own finger (Exod. 31:18b). E's interest in ritual has led to the suggestion that perhaps the writer was a priest,3 for he mentions the prohibition against eating the ischial sinew (Gen. 32:32), and refers to oil libations poured out on, masseboth (standing pillars) (Gen. 28:18; 35:14) and to tithing (Gen. 28:22). At the same time a reforming interest is also apparent. For example, the story of Abraham's near-sacrifice of his son may be a sermonic parable directed against child sacrifice (Gen. 22). The condemnation of the golden calf, a cult symbol in the royal shrines at Bethel and Dan, constitutes a very bold protest (Exod. 32).4

“It is generally agreed, despite slender evidence, that E is a product of the northern kingdom.5 There is more information about Jacob and Joseph, more emphasis on northern shrines of Bethel and Shechem, and less data pertaining to Abraham and Hebron than in J. The use of the Israelite designation of Horeb as the sacred mountain, which appears also in the Elijah cycle (I Kings 19:8), also points to a northern provenance for E.

“E is often given a date in the eighth century B.C., usually during the reign of Jeroboam II (c. 786-746), a prosperous time reflected in the lack of mention of struggle and difficulty in E, or in the ninth century in the time of Jehu (842-815) when pro-Yahwist parties were in control. On the other hand, there is no reason why the writing could not have been produced in the tenth century during the reign of Jeroboam I, immediately following the separation of the two kingdoms. If writings like J and E were a product of the national cult and were used in ritual, it would seem natural that when the royal shrines were erected at Bethel and Dan, E was compiled from the same or similar sources as J. The literature, as we are able to extract it from the Torah, is probably best understood as a product of the developing cult or as the result of a process of progressive interpretation by which the relationship of the northern kingdom to Yahweh continued to be expressed and expanded.

“It has been argued that E lacks J's dramatic simplicity of style and this may be so, but one cannot avoid noting the tense, moving portrayal of the Abraham-Isaac episode of Gen. 22, and the excellent characterizations in the Joseph cycle that reflect the work of a master raconteur. E's objective is that of J: the proclamation of Yahweh's purposes for his people, promised in the past, expressed through salvation history, being realized in the present and giving promise for the future.

“How E came to be combined with J can only be conjectured. When Israel collapsed before Assyria in the eighth century, it is possible that priests from Bethel fled across the border, seeking sanctuary in Jerusalem and bringing with them sacred traditions of their shrine and nation. Why the writings were merged cannot be known. It can only be said that in the editing preference appears to have been given to J materials. No E creation story has survived, although it is possible that the use of the term "Elohim," together with "Yahweh," in Gen. 2:4b-3:24 signifies a fusion of J and E primeval myths.6

Biblical Passages Attributed to E

The Abraham Cycle *Gen. 15:1-3, 5f., 11, 12a, 13-14, 16 Often ascribed to E, but note the name "Yahweh" which was not yet revealed. The material appears to be late, reflecting D influence. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,”1968, infidels.org ]

Gen. 20:1-17: Abraham and Sarah in Gerar.

Gen. 21:8-21: The Hagar story.

Gen. 21:22-32, 34: Abraham and Abimelech at Beer-sheba.

Gen. 22:1-13, 19: Abraham and child sacrifice.

The Jacob Cycle Gen. 28:11-12, 17-18, 19b-21a, 22: Jacob's dream.

Gen. 30:1-8: Jacob and Laban (a conflation of J and E).

Gen. 30:26, 28; 31:2, 4-17, 19-20, 21b-43, 45, 46b, 49-50, 53b-55: Jacob leaves Laban.

Gen. 32:1-2: Jacob at Mahanaim.

Gen. 32:13-21: Jacob and Esau.

Gen. 32:23-32: Jacob wrestles with God and Jacob becomes Israel.

Gen. 33:18-20: Jacob at Shechem.

Gen. 35:1-8: Jacob at Bethel.

Gen. 35:16-20: Birth of Benjamin and death of Rachel.

The Joseph Cycle Gen. 30:22-24: The birth of Joseph (a conflation of J and E).

Gen. 37:5, 9-11, 19-20, 22, 24, 28a, 29-30, 36: Joseph is sold into slavery.

Gen. 40:1-23: Joseph interprets dreams.

Gen. 41:1-45, 47-57: Joseph and Pharoah.

Gen. 42: Joseph and his brothers. (A conflation of J and E. E material may include 42:1, 3-4, 8-25, 29-37.)

Gen. 45:5-8, 15-18, 20, 25-27; 46:1-5: Jacob comes to Joseph.

Gen. 48:1-2a, 7-9a, 10b-12, 15-16, 20-22: Jacob's blessing.

Gen. 50:15-26: Deaths of Jacob and Joseph.

The Moses Cycle Exod. 1:15-2:10: Moses' infancy stories.

Exod. 3:1, 4b, 6, 9-15, 19-22: Moses encounters Yahweh.

Exod. 4:17-18: Moses leaves Jethro.

Exod. 4:20b-21: A warning about Pharaoh.

Exod. 4:27-28: Moses and Aaron

Exod. 5:1-2, 4: Moses and Aaron before Pharaoh.

Exod. 7:15b, 17b, 20b; 9:22-23a, 25a, 35a; 10:12; 13a, 14a, 20-23, 27; 11:1-3: E materials pertaining to the plagues.

Exod. 12:31-42a; 13:17-19; 14:15-19a, 21-23, 26-27a, 28-29: The Exodus.

Exod. 15:20 f.: Miriam's song (vss. 1-18 are a separate expansion).

Exod. 16-18: Basically a conflation of J and E, so combined that any separation is conjectural. (Possible E material = 17:3-6, 8-16, 18:1-27.)

Exod. 19: May contain J-E material at 19:1-3a, 18. The remainder has been overwritten by a redactor.

Exod. 20:1-23:19: Whether or not E contains legal material has been debated. Many scholars place these two law codes in E.

Exod. 20:1-20: The ethical decalogue.

Exod. 20:22-23:19: The Covenant Code (based on an old Canaanite civil code). 23:20-33 is by Rje or Rd.

Exod. 24:12-14, 18b; 31:18b: Moses receives stone tablets of law from God.

Exod. 32:1-8, 15-24, 35: The Golden Calf.

Exod. 33:4-6: Discarding of ornaments.

Exod. 33:7-11: The Tent of Meeting.

Num. 11:1-3: Complaints at Taberah.

Num. 11:16-17: The seventy elders.

Num. 11:24-30: Eldad and Medad.

Num. 12:1-15: Rebellion of Aaron and Miriam.

Num. 13-14: Sending out spies. The E material is closely interwoven with J and P and the following list of E passages is conjectural: 13:17b-20, 22-24, 26b, 28, 30-32; 14:1, 3-4, 11-25, 31-32, 39-45.

Num. 16:1b, 2a, 12-15, 25-26, 27b-34: Dathan and Abiram rebel (E mixed with J and re-edited).

Num. 20:1b: Death of Miriam.

Num. 20:4-13: Water problems.

Num. 20:14-21: Problems with Edomites (contains both J and E).

Num. 21:4-9: The brazen serpent (late addition to J?).

Num. 21:21-25: The battle with Sihon of the Amorites.

Num. 21:33-35: The battle with Og of Bashan.

Num. 22:3b-4, 8-16, 19-21, 35b-41; 23:1-30; 24:1-2, 10-14, 20-25: Oracles of Balaam (interwoven with J).

Num. 25:1-5: Worship at Ba'al Peor (some J?).

Num. 32:1-5, 16-17, 20-27, 34-41: Reuben and Gad settle in Transjordan.

* Asterisks mark passages usually assigned to E but which, according to personal analysis, may not be E.

E Saga