RELIGION IN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA

The God Enki Mesopotamians are credited with developing the first organized religion. They had anthropomorphic gods and epic poetry and related myths and stories that maintained and explained their hierarchy. Mesopotamians believed that gods could foretell all events and also believed in oracles. Mesopotamian religion began with the Sumerians. The Babylonians and then the Assyrians adopted many Sumerian doctrines and myths but gave their gods credit for things like creating the universe.

Religion and government were closely linked in Mesopotamia. The cities were regarded as the property of the gods and human were expected to do what the gods asked of them as directed by the priest-kings. As rulers became more powerful, controlling larger areas of land and more diverse groups of tribes, they increasingly conjured up divine images and referred to themselves as having been selected by the gods to rule. This was true in Mesopotamia, China, Egypt and Japan. It wasn't as true in Greece, which was divided into numerous city states, but made a comeback in Rome which was more of an empire. Some rulers like the Egyptians even viewed themselves as gods.

John Alan Halloran of sumerian.org wrote: “The Sumerians did not have a word for religion, because worshipping the gods at their temples was basic to their existence. As you can imagine, it is difficult to have a name for their religion, when they don't even have a word for religion.” [Source: John Alan Halloran, sumerian.org]

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia” by Jean Bottéro (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Treasures of Darkness: A History of Mesopotamian Religion” by Thorkild Jacobsen (1976) Amazon.com;

“Anunnaki Gods: The Sumerian Religion” by Joshua Free Amazon.com;

“A Handbook of Ancient Religions” by John R. Hinnells (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Religion of Babylonia and Assyria by Theophilus Pinches Amazon.com;

“Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary” by Jeremy Black (1992) Amazon.com;

“The Heavenly Writing: Divination, Horoscopy, and Astronomy in Mesopotamian Culture” by Francesca Rochberg Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamian Cosmic Geography” by Wayne Horowitz (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Social World of the Babylonian Priest” by Bastian Still (2019) Amazon.com

“A Handbook of Gods and Goddesses of the Ancient Near East: Three Thousand Deities of Anatolia, Syria, Israel, Sumer, Babylonia, Assyria, and Elam” by Douglas R. Frayne , Johanna H. Stuckey, et al. (2021) Amazon.com;

“Sumerian Gods and Their Representations” by Irving L. Finkel, Markham J. Geller (1997) Amazon.com;

“Inanna, Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer” by Diane Wolkstein (1983) Amazon.com;

Impact of Religion on the Life of Mesopotamians

Ira Spar of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Religion was a major factor influencing behavior, political decision making, and material culture. Unlike some later monotheistic religions, in Mesopotamian mythology there existed no systematic theological tractate on the nature of the deities.[Source:Spar, Ira. "Mesopotamian Deities", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2009, metmuseum.org \^/]

Morris Jastrow said: “A marked and deep religious spirit pervades throughout the culture of the time. The rulers held their authority directly from the patron deities— “by the grace of God,” as we should now say. They do not generally go so far as to claim divine descent, but they closely approach it. They regard themselves as chosen by the will of the gods. Their strength is derived from Ningirsu, they are nourished by Nin-Kharsag, they are appointed by the goddess Innina. When they go to war the gods march at their side, and the booty is dedicated to these protecting powers. The political fortunes, and indeed the general culture, are thus closely bound up with the religion. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

“Each centre had a chief deity whose position in the pantheon kept pace with the political growth of the centre. At Lagash this chief deity was Ningirsu, a solar deity; at Nippur it was Enlil, originally a personification of the storm; at Cuthah, it was Nergal, likewise a solar deity, and at Ur it was Sin, the moon-god. The chief edifice in the capital of the principality is the temple of the patron deity, alongside of which are smaller sanctuaries within the sacred area, dedicated to the gods and goddesses associated with the main cult. Art is developed around the cult. Such artistic skill was largely employed in the fashioning of votive objects; and even where the rulers erected statues of themselves, these were dedicated to some deity and intended to symbolise the pious devotion of the god’s representative on earth. As further emphasising the bond between religious and secular conditions we find the palaces of rulers at all times adjoining the temple.”

Sumerian Theocratic Government

Stela of Ur-Nammu Sumer was a theocracy with slaves. Each city state worshiped its own god and was ruled by a leader who was said to have acted as an intermediary between the local god and the people in the city state. The leaders led the people into wars and controlled the complex water systems. Rich rulers built palaces and were buried with precious objects for a trip to the afterlife. A council of citizens may have selected the leaders.

Some scholars have described the Mesopotamian system of government as a "theocratic socialism." The center of the government was the temple, where projects like the building of dikes and irrigation canals were overseen, and food was divided up after the harvest. Most Sumerian writing recorded administrative information and kept accounts. Only priests were allowed to write.

Early Sumerians established a powerful priesthood that served local gods, who were worshiped in temples that dominated the early cities. Much of political and religious activity was oriented towards gods who controlled the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and nature in general. If people respected the gods and the gods acted benevolently the Sumerians thought the gods would provide ample sunshine and water and prevent hardships. If the people went against the wishes of the local god and the god was not so benevolent: droughts, floods, famine and locusts were the result.

In Uruk kings took part n important religious rituals. One vase from Uruk shows a king presenting a whole set of gifts to a temple of the city goddess Inana. Kings supported temples and were expected to turn over some of the booty from wars and raids to temples.

See Separate Article: SUMERIAN RULERS, GOVERNMENT, WARFARE africame.factsanddetails.com

Religion and Culture in Mesopotamia

Morris Jastrow said: “The architecture of both temple and palace is massive and, in consequence of the lack of a hard building-material in the Euphrates Valley, it is perhaps natural that the brick constructions developed in the direction of hugeness rather than of beauty. The drawings on limestone votive tablets and on other material during this early period are generally crude. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

“More skill is displayed in incisures on seal cylinders of various kinds of material, bone, shell, quartz, chalcedony, lapis-lazuli, hematite, marble, and agate. Though serving the purely secular purpose of identifying an individual’s personal signature to a business document—written on clay as the usual writing-material—these cylinders incidentally illustrate the bond between culture and religion by their engraved designs, which are invariably of a religious character, —such as the adoration of deities, sacrificial scenes, or representations of myths or mythical personages. Though marred frequently by grotesqueness, the metal work—in copper, bronze, or silver—is on the whole of a relatively high order, particularly in the portrayal of animals. The human face remains, however, without expression, even where, as in the case of statues chiselled out of the hard diorite, imported from Arabia, the features are carefully worked out.

“This close relationship between religion and culture, in its various aspects—political, social, economic, and artistic,—is thus the distinguishing mark of the early history of the Euphrates Valley that leaves its impress upon subsequent ages. Intellectual life centres around religious beliefs, both those of popular origin and those developed in schools attached to the temples, in which, as we shall see, speculations of a more theoretical character were unfolded in amplification of popular beliefs.”

Religious Literature in Mesopotamia

Dumuzi Morris Jastrow said: “The bulk, nay, practically, the whole of the literature of Babylonia was of a religious character, or touched religion and religious beliefs and customs at some point, in accord with the close bond between religion and culture which, we have seen, was so characteristic a feature of the Euphratean civilisation. The old centres of religion and culture, like Nippur, Sippar, Cuthah, Uruk, and Ur, had retained much of their importance, despite the centralising influence of the capital of the Babylonian empire. Hammurabi and his successors had endeavoured, as we have seen, to give to Marduk the attributes of the other great gods, Enlil, Anu, Ea, Shamash, Adad, and Sin, and, to emphasise it, had placed shrines to these gods and others in the great temples of Marduk, and of his close associate, Nebo, in Babylon, and in the neighbouring Borsippa. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

“Along with this policy went, also, a centralising tendency in the cult and, as a consequence, the rituals, omens, and incantations produced in the older centres were transferred to Babylon and combined with the indigenous features of the Marduk cult. Yet this process of gathering in one place the literary remains of the past had never been fully carried out. It was left for Ashurbanapal to harvest within his palace the silent witnesses to the glory of these older centres. While Babylon and Borsippa constituted the chief sources whence came the copies that he had prepared for the royal library, internal evidence shows that he also gathered the literary treasures of other centres, such as Sippar, Nippur, Uruk.

“The great bulk of the religious literature in Ashurbanapal’s library represents copies or editions of omen-series, incanta-tion-rituals, myths, legends, and collections of prayers, made for the temple-schools, where the candidates for the various branches of the priesthood received their training. Hence we find supplemental to the literature proper, the pedagogical apparatus of those days—lists of signs, grammatical exercises; analyses of texts, texts with commentaries, and commentaries on texts, specimen texts, and school extracts, and pupils’ exercises.”

Mesopotamian Gods

Mesopotamians worshiped a wide array of gods, including personal gods, gods associated with each-state and gods of the sun, the moon and the planets. There were also gods for everything imaginable: broken hearts, leatherworking, sexual intercourse, weapons and the destruction of cities. Each topic covered by a god had its own rules and regulations which was supposedly enforced by the god that created it.

In the beginning each Sumerian city-state had its own pantheon of gods. Over time separate groups of gods fused into a pantheon of gods worshiped by everyone in Mesopotamia as well as by people in other regions.

Sumerian gods ate, drank, had sex and bore children just like people. The Mesopotamians had myths to go along with their gods to help explain things like why Sumer was chosen as the center of civilization and why there is a heaven and earth. The answer to the second question the Babylonians said that Marduk defeated a dragon by slitting it in two "like a shellfish."

See Separate Article: MESOPOTAMIAN DEITIES africame.factsanddetails.com

Mesopotamian Pantheon of Gods

There were hundreds of Mesopotamian gods. Sumerian gods included Inana, the great Sumerian goddess of fertility, war, love and success; Ninhursag or Ninmah, the earth goddess; Nergal, the god of death and disease; Anu, the ruler of the sky and the principal god in Uruk; Enlil, storm god and the main god in Nippur; and Sin, the god of the moon. Anu was the supreme being until Uruk was taken over the by city of Nippur and their local god Enlil became the god of gods. These gods were also worshiped by the Babylonians and Assyrians.

The main Babylonian god was Marduk and the main Assyrian god was Ashur. Ishtar, the Babylonian goddess of fertility and love, was worshiped by both the Babylonians and Assyrians. The Babylonian and Assyrians created a triad of gods with the addition of an amicable God of the Underworld (Enki or Ea). The Mesopotamians gave each god a number: Anu was 60, Enhil 50, Ea 40, Sin 30, Shamash 20 and Ishtar 15. Some deities had consorts.

Mesopotamia gods were also linked to and had similarities with Gods in other cultures. Ishtar evolved into Diana and Artemis in Asia Minor and Aphrodite in Greece. Ishtar was believed to have the power to provide her worshipers with children and lambs. Her son Tammuz was associated with crops. In the leans months of summer people fasted until Tammuz rose from dead and made the world green again. The myth is similar to the Greek myth of Demeter and Persephone. In the Bible the prophet Ezekiel was disgusted by women in Jerusalem who were “weeping for Tammuz.”

The sun god Shamash crossed the heavens in a chariot as the Egyptian god Aren in Mesopotamian and Egyptian times and the Greek god Apollo would later do. During the night he traveled through the underworld and passed judgement on the dead. The Assyrians had a weather god named Adad who carried lighting bolts in his hand and bore a striking resemblance to Zeus.

Mesopotamian Creation Myth

Star of Shamash The Sumerians, like the early Greeks, believed the earth was a disk surrounded by oceans. They believed the entire universe was spawned in a primeval sea. First the sun, the moon and the planets emerged and then people, plants and animals. The Babylonians believed that there was a massive body of water inside the earth from which all life sprung. The universe was a great vault of heavens over the earth.

In the Sumerian creation myth, the world was once watery chaos. The mother of chaos was an immense dragon named Tiamet. Gradually the gods appeared and decided to battle Tiamat and her army of dragons to bring order to the world.As Tiamat approached, Enlil shoved some huge winds down her mouth and Tiamat swelled up and was unable to move. Tiamat’s body was then split open, with the upper forming the sky and the lower half forming the earth. Tiamat’s husband was beheaded and mankind emerged from his blood mixed with clay.

The Sumerians described the creation of men and women as a god-assisted birth while the Babylonians asserted that men were created out of clay and blood by a divine word to help the gods build canals. Humans once rebelled against the Gods by going on strike. On another occasion one god brought plagues and famine to the earth because humans were making too much noise and depriving him of sleep.

Anu, Enlil, Shamash, Ea and The Creation of Man See Important MESOPOTAMIAN DEITIES africame.factsanddetails.com

Mesopotamia and the Bible

The first 11 chapters of Genesis are largely set in Mesopotamia. Eden is a Sumerian word meaning “steppe,” and was a district in Sumer. The Tower of Babel was in Babylon. The Hanging Gardens may have inspired the story of the Garden of Eden. According to Genesis Abraham and Cain and Abel and numerous other Biblical figures were born in Mesopotamia and the first cities founded after the flood were Babel (Babylon), Erech (Uruk), and Accad (Akkad) there.

Nebuchadnezzar Cuneiform tablets found in Ebla mention the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah and contain the name of David. They also mention Ab-ra-mu (Abraham), E-sa-um (Esau) and Sa-u-lum (Saul) as well as a knight named Ebrium who ruled around 2300 B.C. and bears an uncanny resemblance to Eber from the Book of Genesis who was the great-great grandson of Noah and the great-great-great-great grandfather of Abraham. Some scholars suggest that Biblical reference are overstated because the divine name yahweh (Jehovah) is not mentioned once in the tablets.

The Babylonians also had myths also that bore of striking resemblance to the creation of Eve from Adam’s rib and the story of Noah's Ark. See Literature.

Abraham was born under the name Abram in the Sumer city of Ur in Mesopotamia (in present day Iraq). According to Genesis, Abraham was the great, great, great, great, great, great, great, great grandson of Noah and was married to Sarah.Genesis 11:17-28, reads “Terah Begot Abram, Nahor, and Haran, and Haran begot Lot. And Haran died in the lifetime of Terah his Father in the land of his birth, Ur of Chaldees.”

See Separate Article BIBLE AND MESOPOTAMIA factsanddetails.com

Mesopotamian Temples

In Mesopotamia temples were conceived as houses of god they housed, comparable to the houses of a noble or king. The temple housed the statue of the god, thought to contain the essence of the god. The temple building itself, and its symbolism, was considered a reflection of the cosmic abode of the god. The rites of worship consisted mainly in ministering to the physical needs of the gods. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

Temples were often the most central and important buildings in Mesopotamian city states. They were usually devoted to individual deities and could be quite elaborate if the city was rich. The largest temples were ziggurats (see Below).

Mesopotamian temple usually contained a central shrine with a statute of the deity placed on a pedestal before an altar. The temples were watched over by priests and priestesses that lived in apartment in the temple. On the temple grounds were other quarters for officials, accountants, musicians and custodians as well as structures that held treasures, weapons and grain.

Sumerian pilgrims visited temples honoring Anau in Uruk and Enlil in Nippur. The largest temple in Mesopotamia was a temple honoring Marduk in Babylon. Inside was golden statue of statues of Marduk that weighed perhaps 5,000 pounds and 55 shrines devoted to lower echelon gods. The 200 foot long, 70-foot high ziggurat built in Ur had three platforms, each a different color, and a silver shrine at the top. [“World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder, Facts on File Publications, New York]

Mesopotamia temples often had off center entrances so that common people could catch a glimpse of the inner sanctuary when they looked inside. Temples in Uruk, Ashur and Babylon all have this feature.

See Separate Article: MESOPOTAMIAN TEMPLES africame.factsanddetails.com

Ziggurats

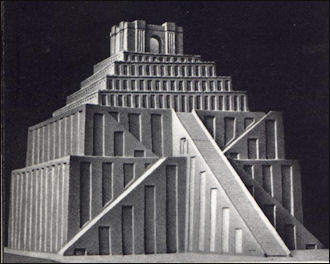

Sumerian Ziggurat The largest Sumerian and Mesopotamian structures were ziggurats — somewhat tower-like stepped pyramids made from mud brick and topped by temples to gods and goddess. They first appeared around 3500 B.C. In ancient times, every major Mesopotamian city had at least one.

In the forth century an Egyptian claimed that ziggurats "had been built by giants who wished to climb up to heaven. For this impious folly some were struck by thunderbolts; others, at God's command, were afterwards unable to recognize each other; all the rest fell headlong into the island of Crete, whither God in His wrath had hurled them."

Ziggurat means both the summit of a mountain and man-made tower. The Babylonians described them as a "Link Between Heaven and Earth." There are no mountains in Mesopotamia. Scholars believe ziggurats were built as artificial mountains to help man reach the gods and the gods reach man.

The remains of 33 ziggurats have survived until the 21st century. Since ziggurats were made of mud bricks they held up less against the ravages of time than the Pyramids of Egypt, which were built of stone. The Ziggurat of Choga Zambil (19 miles from Haft Tepe, Iran) is the world's largest ziggurat. Its outer base is 244-x-344 feet and the "fifth box" — 164 feet above the base — measures 92-x-92-feet. One of the most famous ziggurats — the one in Samarra, Iraq — is not a ziggurat at all but the minaret of an A.D. 8th century mosque.

The oldest structure in reasonably good condition left from ancient Mesopotamia is the 4500 year-old Ziggurat of King Urnammu in Ur. It originally consisted of three levels, of which only the third remains. It looks sort of like a 50-foot wall castle wall filled in with dirt and ascended by a staircase. The main ziggurat of Ur was dedicated to the moon god Nanna. It rises 65 feet from a 135-by-200-foot base and is 4,100 year old. After the invasion of Iraq by the United States it was enclosed within a U.S. military base.

See Separate Article: ZIGGURATS: SIZE, ARCHITECTURE AND THE TOWER OF BABEL africame.factsanddetails.com

Mesopotamian Priests and Worshipers

Sumerian high priests were believed to be mouthpieces of the gods. They presided over rituals and often divined the future by reading the entrails of sheep or goats.

Temple priests and priestess lived in apartment in the temple. The sex of the overseer was usually opposite that of the major deity in the temple. Under the main priest or priestess was of courtier of minor priests, each of whom performed a different task at the temple such as sacrificing, anointing or pouring libations. Quarters for sacred prostitutes, temple slaves and eunuchs were placed around the temple. ["World Religions" edited by Geoffrey Parrinder, Facts on File Publications, New York]

Kurlil Individual Mesopotamians were supposed to pray daily to deities of their choice and honor them with sacrifices, hymns and incense offerings. According to one Mesopotamian Counsels of Wisdom axiom: "Reverence begets favor, sacrifice prolongs life, and prayer atones for guilt.”

Wealthy worshipers placed inscribed jewelry and bowls next to the statues and other devotees submitted letters of complaint. During prayers, the faithful kneeled, prostrated themselves and rose holding one hand in front of the mouth or raising both hands in the air. Many people kept statuettes of gods in their house. Many houses had small niches to keep them.

The Babylonian described a sinner as "one who has eaten what is taboo to his god or goddess, who has 'no' for 'yes' or has said 'yes' for 'no,' who has pointed his finger (falsely accusing) a fellow man...caused evil to be spoken, has judged incorrectly, oppressed the weak, estranged a son from his father or a friend from a friend, who has nor freed the captive..." Sins could be absolved by a penitential psalm, prayer or lament or an expiatory sacrifice in which a "lamb is substitute for man." Demons were exorcized by a priest who transferred the demon to a wax or wooden figure that was thrown in a fire. [ “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder, Facts on File Publications, New York]

Mesopotamian Sacrifices and Religious Rituals

Like humans, gods had to be fed everyday. As part of the daily temple rituals, gods were given the best cuts of meat as well as barley bread, onions, dates , fruit, fish, fowls, honey, ghee and milk — all food consumed by the Mesopotamians themselves.”

In ancient Babylonia, the king used to shake hands with a statue of the premier god Marduk on New Year's day to signify the transcendence of divine power for another year. The Assyrians carried on the tradition after they conquered Babylon.

Sacrifices were central to Mesopotamian religion. A cuneiform tablet found in Iraq record how a ruler's wife sacrificed livestock to the gods in 2350 B.C. After an animal was sacrificed the blood was poured into goblets and the lungs and liver were examined for omens.

Nippur

Nippur (pronounced nĭ poor’) was a major of religious center of Mesopotamia located 160 kilometers south of Baghdad or 80 kilometers southeast of Babylon on the canal Sha al-Nil, which was at one time, perhaps when Nippur was founded, was a separate branch of the Euphrates River. Established by the pre-Mesopotamian“Ubaid” people around 4,500 B.C., Nippur was seat of the cult of Enlil, one of the most important Mesopotamian gods. It was never an important city-state and was ruled by other city-states. It is possible, but improbable, that Nippur was the "Calneh" mentioned in Genesis 10 of the Old Testament.

Nippur Spindle

Built on the Euphrates and at its height around 2500 B.C., Nippur was the home of important temple dedicated to Enlil, a storm god sometimes treated like supreme deity, and other temples, including one dedicated to Bau (Gula), the Mesopotamian goddess of healing.

According to Biblegate: “Nippur was the seat of the cult of Enlil, and the ancient renown of this god insured his city the continued care on the part of the Babylonian kings. As late as the 7th cent. B.C., the Assyrian king, Ashurbanipal, restored Enlil’s temple. Nippur was the seat of Sumer’s most important “academy” and in the lit. composed and redacted in this academy, Nippur and its leading deities, Enlil, his wife Ninlil, and his son Ninurta, played a large role. Excavators found some 30-40,000 tablets and fragments at Nippur, and about 4,000 of these are inscribed with Sumer. works.

J. Frederic McCurdy wrote in the Jewish Encyclopedia: Nippur’s “ancient renown was due partly to its central position among the Semitic settlements, and especially to the fact that it was the first known great seat of the worship of Bel. The name of this chief Babylonian god, identical with the Canaanitish Ba'al, suggests that his worship at Nippur was the consolidation of that of many local Ba'als, and that Nippur obtained its religious preeminence by having gained the leadership among the Semitic communities. In any case its predominance was actually established at least as early as 5000 B.C. [Source: J. Frederic McCurdy, jewishencyclopedia.com; Peters, Nippur or Explorations and Adventures on the Euphrates, 1897; Hilprecht, Explorations in Bible Lands, 1903, pp. 289-568.]

See Separate Article NIPPUR: THE RELIGIOUS CENTER OF MESOPOTAMIA africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024