Home | Category: Neo-Babylonians

NEO-BABYLONIANS

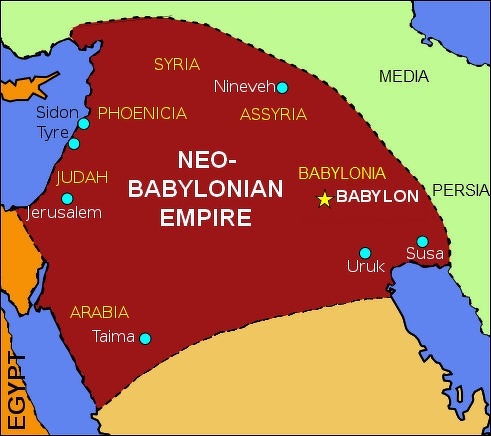

Walls of Babylon and Temple of Bel Babylon was reborn under the Neo-Babylonians (792 to 595 B.C.) who defeated the Assyrians and established a large empire. The empire reached its peak in the 6th century B.C. under Nebuchadnezzar, the famous Biblical ruler.

The Neo-Babylonians are also known by their Biblical name the Chaldeans. Sometimes their state is called the Second Babylonian Empire.

Neo-Babylonian dynasty

Nabopolassar: 625–605 B.C.

Nebuchadnezzar II: 604–562 B.C.

Amel-Marduk: 561–560 B.C.

Neriglissar: 559–556 B.C.

Labashi-Marduk: 556 B.C.

Nabonidus: 555–539 B.C.

[Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. "List of Rulers of Mesopotamia", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/meru/hd_meru.htm (October 2004)

The Neo-Babylonians began as a little known Semitic people. They rebuilt Babylon and established it as their capital. Their army sacked Jerusalem and enslaved entire races of people. After the Assyrian empire collapsed Jerusalem enjoyed 70 years of independence before it was taken over by Nebuchadnezzar after a year and a half siege.Much of the debauchery associated with Babylon occurred under the Neo-Babylonians. According the Bible, debauched partiers at King Belshazzar's feast were warned by the prophet Daniel that their kingdom would fall with the words “ Mene, Mene, Tekel, Upharsin”.Daniel lived in Babylon. He impressed the Babylonian court with his prophetic interpretations of Nebuchadnezzar’s death

Neo-Babylonians

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology Magazine: After living under the kings of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–609 B.C.) for several centuries, Babylonians, led by a local chieftain named Nabopolassar (r. 626–605 B.C.), revolted and, after a protracted civil war, seized power, establishing the Neo-Babylonian Empire. This ushered in a period that saw Babylon become an imperial capital as its armies conquered much of the territory previously ruled by Neo-Assyrian kings. Nabopolassar was succeeded by his son Nebuchadnezzar II, who was known for his military conquests, including the capture of Jerusalem, and his building projects, which included the construction of the city’s famed Ishtar Gate. The gate was decorated with colorful molded and glazed bricks, some of which depict a mušhuššu, the mythological dragon that was Marduk’s totemic animal. In the last decade of the seventh century B.C., Babylonian forces conquered the final remnants of the Neo-Assyrian Empire to the north. [Source: Eric A. Powell, Archaeology Magazine, March/April 2022]

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“A History of Babylon (2200 BC - AD 75" by Paul-Alain Beaulieu (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian World” by Gwendolyn Leick (2007) Amazon.com;

The Royal Inscriptions of Nabopolassar (625-605 BC) and Nebuchadnezzar II (604-562 BC)” by Jamie Novotny and Frauke Weiershäuser (2024) Amazon.com;

“Nabonidus and Belshazzar: A Study of the Closing Events of the Neo-Babylonian Empire” by Raymond Philip Dougherty (2008) Amazon.com;

“Babylonia: A Very Short Introduction” by Trevor R. Bryce (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Ishtar Gate, The Processional Way, The New Year Festival of Babylon” by Joachim Marzahn (1995) Amazon.com;

“Babylonia” by Costanza Casati (2025) Novel Amazon.com;

“Babylonians” by H. W. F. Saggs (1995) Amazon.com;

“The Greatness That Was Babylon” by H. W. F. Saggs (1962) Amazon.com;

“The Babylonian Empire” by Enthralling History (2022) Amazon.com;

“The City of Babylon: A History, C. 2000 BC - AD 116" by Stephanie Dalley (2021) Amazon.com;

“The First Great Powers: Babylon and Assyria” by Arthur Cotterell (2019) Amazon.com;

“The History of Babylonia and Assyria” by Hugo Winckler (1892) Amazon.com;

“Civilizations of Ancient Iraq” by Benjamin R. Foster and Karen Polinger Foster ((2009) Amazon.com;

“A History of the Ancient Near East” by Marc Van De Mieroop (2003) Amazon.com;

“Nippur IV: The Early Neo-Babylonian Governor's Archive from Nippur (Oriental Institute Publications) by Steven W. Cole (1996) Amazon.com;

Achievements of the Neo-Babylonians

Ishtar Gate

The Neo-Babylonians made great contributions to science, astronomy and mathematics, which were later passed on to the Greeks. Many of the achievements in these fields credited to the Babylonians were actually accomplished by the Neo-Babylonians.

“On Babylon his chief efforts were concentrated; the marvellous constructions to which it owes its eminence in tradition and legend were his achievement. It was he who erected the famous “Hanging Gardens,” a series of raised terraces covered with various kinds of foliage, and enumerated among the “Seven Wonders of the World.” A sacred street for processions was built by him leading from the temple of Marduk through the city and across the river to Borsippa— the seat of the cult of Nebo, whose close association with Marduk is symbolised by their relationship of son and father. This street, along which on solemn occasions the gods were carried in procession, was lined with magnificent glazed coloured tiles, the designs on which were lions of almost life size, as the symbol of Marduk. The workmanship belongs to the best era of Euphratean art. The high towers known as Zikkurats, attached to the chief temples at Babylon and Borsippa, were rebuilt by him and carried to a height greater than ever. By erecting and beautifying shrines to all the chief deities within the precincts of Marduk’s temple, and thus enlarging the sacred area once more to the dimensions of a precinct of the city, he wished to emphasise the commanding position of Marduk in the pantheon. In this way, he gave a final illustration of how indissolubly religious interests were bound up with political aggrandisement.

“The impression, so clearly stamped upon the earliest Euphratean civilisation,—the close bond between culture and religion,—thus marks with equal sharpness the last scene in her eventful history. In Nebuchadnezzar’s days, as in those of Sargon and Hammurabi, religion lay at the basis of Babylonia’s intellectual achievements. The priests attached to the service of the gods continued to be the teachers and guides of the people. The system of education that grew up around the temples was maintained till the end of the neo-Babylonian empire, and even for a time survived its fall. The temple-schools as integral parts of the priestly organisation had given rise to such sciences as were then cultivated—astronomy, medicine, and jurisprudence. All were either attached directly to religious beliefs, as medicine to incantations, astronomy to astrology, jurisprudence to divine oracles, or were so harmoniously bound up with the beliefs as almost to obscure the more purely secular aspects of these mental disciplines. The priests continued to be the physicians, judges, and scribes. Medicinal remedies were prescribed with incantations and ritualistic accompaniments. The study of the heavens, despite considerable advance in the knowledge of the movements of the sun, moon, and planets, continued to be cultivated for the purpose of securing, by means of observations, omens that might furnish a clue to the intention and temper of the gods.”

Babylon Under the Neo-Babylonians

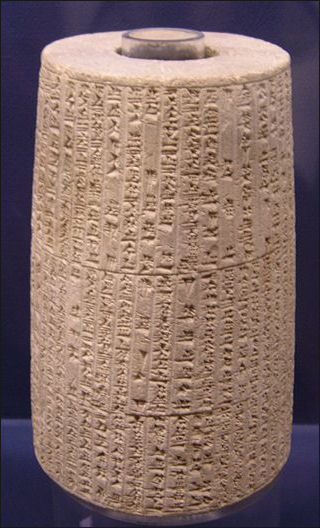

Nebuchadnezzar's Barrel cylinder Babylon declined under the Assyrians but was reborn and expanded to the east bank of the Euphrates under King Nebuchadnezzar II and the Neo-Babylonians.

Nebuchadnezzar returned Babylon to it place as the greatest city in the world. He built the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the Seven Wonders of the World; a stone bridge across the Euphrates; and the Ishtar gate, a huge monumental structure guarded by stone bulls and dragons. Processions honoring the god Marduk marched between the Ishtar gates and the Temple of Marduk, the chief Babylonian deity.

In Nebuchadnezzar’s time Babylon was built in the shape of a 1.6 mile square and was exquisitely planned. It was surrounded by massive walls and centered around 25 major streets paved with slabs of stone that were organized into a grid. Gates made of brass penetrated the walls. A massive bridge spanned the Euphrates which ran through the middle of the city. Mud brick palaces were adorned with glazed tiles of blue, red and green.

At its peak Babylon was a religious center that was the Jerusalem of its day. It was multi cultural and a free city for refugees. The most elaborate temple was dedicate to Marduk, the patron God of Babylon. Extemenanki — a brightly painted, 300-foot-high, stepped ziggurat — that stood near the Temple of Marduk may have been the inspiration for the Tower of Babel. The temples not only supported a caste of priests but also a sages and prophets such as Daniel. In the markets were silver, gold, bronze, ivory, frankincense, myrrh, marble, wine, grains, imported woods brought in by caravans and ships from as far away as Africa and India.

Babylon lost in position as a the most important city in the region when it was conquered by the Persians under Cyrus the Great in 539 B.C. but remained an important trading and commerce center. It was still going strong when Alexander the Great arrived here at the end of his great campaign of conquest. He reportedly died in one of Nebuchadnezzar’s palaces. His successor Seleucia built a new city along a part of the Euphrates with a deeper channel. After this Babylon declined and buildings were reduced to foundation as building materials were scavenged from them. Around A.D. 75 Babylon was abandoned.

Late Iron Age Mesopotamia (c. 750–540 B.C.)

Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: The last two centuries of Mesopotamian independence under Akkadian-speaking rulers restored first Assyria and then Babylonia briefly to a preeminent position in the Near East, and brought these lands into almost constant contact with the West. They left an indelible impress on both Hebrew and Greek sources which, until the decipherment of cuneiform were, in fact, virtually the only materials for the recovery of Mesopotamian history. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

The accession of Nabunasir (Nabonassar) in Babylonia in 747 seems to have been regarded by the native sources themselves as ushering in the Mesopotamian revival. The scribes of Babylon inaugurated a reform of the calendar which systematized the intercalation of a 13th month, on the basis of astronomical calculation rather than observation, seven times in every 19 years, according to the so-called Metonic cycle; taken over later by the Jews, it continues as the basis of the Jewish lunisolar calendar to the present.

Babylonia was by now divided largely between urbanized Chaldeans and still mainly rural Arameans, and since the Chaldeans soon became the principal experts of Babylonian astronomy, the very word Chaldean came to be equated with "astronomer, sage" in Hebrew (Dan. 2:2), Aramaic (Dan. passim), and Greek. These astronomers now began to keep monthly diaries listing celestial observations together with fluctuations in such matters as commodity prices, river levels, and the weather, as well as occasional political events. Perhaps on the basis of the last, they also created a valuable new historiographic record, the Babylonian Chronicle, into which they entered the outstanding events of each year. In the Ptolemaic Canon, the "Nabonassar Era" was recognized as a turning point in the history of science by Hellenistic astronomy.

Nabonassar, the Neo-Babylonians and Assyrians

Early the first Neo-Babylonian ruler Nabonassar was but a minor figure. Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: When he enlisted the help of his greater Assyrian contemporary Tiglath-Pileser III (744–727) in his struggles against both Chaldeans and Arameans, the step proved as fateful as did that of Ahaz of Judah (735–716; sole ruler 731–716) against the Syro-Ephraimite coalition. Tiglath-Pileser III was a usurper, the beneficiary of still another palace revolt that had unseated his weak predecessor. He and his first two successors changed the whole balance of power in the Near East, destroying Israel among many other states, and reducing the rest, including Judah, to vassalage. They found Assyria in a difficult, even desperate, military and economic situation, but during the next 40 years they recovered and consolidated its control of all its old territories and reestablished it firmly as the preeminent military and economic power in the Near East. Only the outlines of the process can be given here. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

After four years of bloody warfare, Ashurbanipal emerged victorious, but at a heavy price. The Pax Assyriaca had been irreparably broken, and the period of Assyrian greatness was over. The last 40 years of Assyrian history were marked by constant warfare in which Assyria, in spite of occasional successes, was on the defensive. At the same time the basis for a Babylonian resurgence was being laid even before the final Assyrian demise.

Ashurbanipal had installed a certain Kandalanu as loyal ruler in Babylon after crushing his brother's rebellion. When this regent died in 627, however, Babylonia was without any recognized ruler for a year. Then the throne was seized by Nabopolassar (625–605), who established a new dynasty, generally known as the neo-Babylonian, or Chaldean dynasty.

Eclipsing of the Assyrians by the Neo-Babylonians

Morris Jastrow said: “After the death of Ashurbanapal in 626 B.C., the decline of Assyria sets in and proceeds so rapidly as to suggest that the brilliancy of his reign was merely the last flicker of a flame whose power was spent—an artificial effort to gather the remaining strength in the hopeless endeavour to stimulate the vitality of the empire, exhausted by the incessant wars of the past centuries. Babylonia survived her northern rival for two reasons. Forced by the superior military power of Assyria to a policy of political inaction or of fomenting trouble for Assyria among the nations that were compelled to submit to her control, Babylonia did not engage in expeditions for conquest, which eventually weaken the conqueror more than the conquered. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911 ]

“Instead of war, commerce became the main occupation of the inhabitants of the south. Through the spread of its products and wares, its culture, art, and religious influence were extended in all directions. The more substantial character of the southern civilisation, the result of an uninterrupted development for many centuries, and not, as in the case of Assyria, a somewhat artificial albeit successful graft, lent to Babylonia a certain stability, and provided her with a reserve force, which enabled her to withstand the loss of a great share of her political independence. After the fall of Assyria, there came to the fore a district of the Euphrates Valley in the extreme south—known as Chaldea—which had always maintained a certain measure of its independence, even during the period of strongest union among the Euphratean states, and not infrequently had given the rulers of Babylon considerable trouble.

Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: Although the Assyrian military machine continued to be a highly effective instrument for almost 20 years, Nabopolassar successfully defended Babylonia's newly won independence and, with the help of the Medes and of Josiah of Judah (639–609), finally eliminated Assyria itself. The complete annihilation of the Assyrian capitals — Nineveh, Calah, Ashur, Dur-Sharrukin — between 615 and 612 is attested in part by the Babylonian Chronicle and even more tellingly in the contemporaneous world can still be measured in the prophecies of Nahum, and possibly of Zephaniah. Only Egypt remained loyal to Assyria, and Pharaoh Neco's efforts to aid the last remnants of Assyrian power at Haran under Ashur-uballi II (611–609) were seriously impaired by Josiah at Megiddo in 609. The last Assyrian king fled Haran in the same year, and Assyrian history came to a sudden end. Four years later, the Battle of Carchemish (605) consolidated the Babylonian success with a defeat of the Egyptians by the crown prince, who presently succeeded to the throne as Nebuchadnezzar II (604–562). The Chaldean empire fell heir to most of Assyria's conquests and briefly regained for Babylonia the position of leading power in the ancient world. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

.

Early History of the Second Babylonian, or Chaldean, Empire

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia:“With the death, in 626 B.C., of Kandalanu (the Babylonian name of Assurbanipal), King of Assyria, Assyrian power in Babylon practically ceased. Nabopolassar, a Chaldean who had risen from the position of general in the Assyrian army, ruled Babylon as Shakkanak for some years in nominal dependence on Ninive. Then, as King of Babylon, he invaded and annexed the Mesopotamian provinces of Assyria, and when Sinsharishkun, the last King of Assyria, tried to cut off his return and threatened Babylon, Nabopolassar called in the aid of the Manda, nomadic tribes of Kurdistan, somewhat incorrectly identified with the Medes. Though Nabopolassar no doubt contributed his share to the events which led to the complete destruction of Ninive (606 B.C.) by these Manda barbarians, he apparently did not in person co-operate in the taking of the city, nor share the booty, but used the opportunity to firmly establish his throne in Babylon.[Source: J.P. Arendzen, transcribed by Rev. Richard Giroux, Catholic Encyclopedia |=|]

“Though Semites, the Chaldeans belonged to a race perfectly distinct from the Babylonians proper, and were foreigners in the Euphrates Valley. They were settlers from Arabia, who had invaded Babylonia from the South. Their stronghold was the district known as the Sealands. During the Assyrian supremacy the combined forces of Babylon and Assyria had kept them in check, but, owing probably to the fearful Assyrian atrocities in Babylon, the citizens had begun to look towards their former enemies for help, and the Chaldean power grew apace in Babylon till, in Nabopolassar, it assumed the reins of government, and thus imperceptibly a foreign race superseded the ancient inhabitants. The city remained the same, but its nationality changed. Nabopolassar must have been a strong, beneficient ruler, engaged in rebuilding temples and digging canals, like his predecessors, and yet maintaining his hold over the conquered provinces. The Egyptians, who had learnt of the weakness of Assyria, had already, three years before the fall of Ninive, crossed the frontiers with a mighty army under Necho II, in the hope of sharing in the dismemberment of the Assyrian Empire. How Josias of Juda, trying to bar his way, was slain at Megiddo is known from IV Kings, xxiii, 29. |=|

Nebuchadnezzar II (Nebuchadnezzar of the Bible)

Nebuchadnezzar II (ruled 604-561 B.C.) took Babylon from the Assyrians, repelled the Persians, captured Jerusalem, enslaved the Jews, revived Babylon and created a Neo-Babylonian empire. A cuneiform inscription from the Ishtar Gate from Babylon (575 B.C.) in the Pergamon museum in Berlin reads, "Nebuchadnezzar, King of Babylon, the pious prince...the highest priest...the never tiring governor...the wise and humble man, the trustee of Esagika and Ezida [two religious shrines], the first born sun of Nabopolassar, King of Babylon — am — I."

Nebuchadnezzar II should not be confused Nebuchadnezzar I. Nebuchadnezzar I (Akkadian: Nabu-kudurri-usur meaning "Nabu, protect my eldest son" or "Nabu, protect the border") was the king of the Babylonian Empire from about 1125 B.C. to 1103 B.C.

Solomon's Temple was partly destroyed and the Ark of the Covenant was lost when Nebuchadnezzar and the Babylonians sacked Jerusalem in 586 B.C. In a Babylonian chronicle Nebuchadnezzar boasted theat he “captured the city and...took heavy tributes and brought it back to Babylon.” The Bible has a similar account except that the “tributes” are referred to as “all the treasures of the Temple and the royal palace.” The fate of the Ark is not known. According to one legend it was stolen by the illegitimate son of Solomon and Sheeba and taken to Ethiopia and placed in a church in Aksum, where only a guardian monk has access to it. A modest Second Temple was built in 539 B.C.

See Separate Article: NEBUCHADNEZZAR II (RULED 604-561 B.C.), HIS CONQUESTS AND THE BIBLE africame.factsanddetails.com

Babylon

Golden Age of Babylonia Under the Neo-Babylonians

Juan Luis Montero Fenollós wrote in National Geographic History: Babylon enjoyed its heyday during the seventh and sixth centuries B.C., when it was believed to be the largest city in the world. A new dynasty founded by a tribe known as the Chaldeans had wrested control from the Assyrians in the early 600s B.C. The second ruler of the Chaldean line became notorious for both cruelty and opulence: Nebuchadrezzar II, the king who sacked Jerusalem and sent the captive Jews to the capital of his new and increasingly powerful regional empire. [Source: Juan Luis Montero Fenollós, National Geographic History, January/February 2017]

A successful military man, Nebuchadrezzar used the wealth he garnered from other lands to rebuild and glorify Babylon. He completed and strengthened the city’s defenses, including digging a moat and building new city walls. Beautification projects were on the agenda as well. The grand Processional Way was paved with limestone, temples were renovated and rebuilt, and the glorious Ishtar Gate was erected. Constructed of glazed cobalt blue bricks and embellished with bulls and dragons, the city gate features an inscription, attributed to Nebuchadrezzar, that says: “I placed wild bulls and ferocious dragons in the gateways and thus adorned them with luxurious splendor so that people might gaze on them in wonder.” The most famous of the eight gates Nebuchadrezzar II built around Babylon, Ishtar was dedicated to Ishtar, goddess of love and war, and was the crowning glory of the king’s homage to Babylon’s ancient Akkadian past. It can nwo be seen in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin.

Babylon reached its zenith under Nebuchadrezzar II, when its outer wall—built to the northeast of the city center, shown above—contained a total urban area of over three square miles. The king wanted its monuments to dazzle with a size and grandeur never seen before. 1. Ishtar Gate: The city’s main entrance was decorated with blue brick and creatures called “mushussu,” an Akkadian dragon with a body made out of other animals. 2. Processional Way: This road led from the palaces to the temples. A statue of Marduk was paraded along it during the Babylonian New Year.3. Etemenanki: Completed by Nebuchadrezzar II, this ziggurat was consecrated to Marduk. A temple topped its six terraces. 4. Esagila: Babylon’s principal deity Marduk, his wife Zarpanitu, and his son Nabu were all worshipped together at this temple complex. Babylon reached its zenith under Nebuchadrezzar II, when its outer wall—built to the northeast of the city center, shown above—contained a total urban area of over three square miles. The king wanted its monuments to dazzle with a size and grandeur never seen before.

Decline and Fall of Neo-Babylonia After Nebuchadnezzar II

After Nebuchadnezzar’s death, Babylon once again declined. Babylonian was given up to the Persians without a fight as Cyrus the Great and his armies marched westward out of Iran. According to Herodotus the Persians under Cyrus caught the Babylonian completely by surprise and even as the Persians were breaching Babylon’s outer defenses the people “engaged in a festival; continued dancing and reveling.” When Cyrus entered the city he forbade looting and freed the Jews. See Persians

With the end of the Neo-Babylonians the Mesopotamian age came to an end. The focal point of the Middle East and the Mediterranean switched to Persia and then Greece and then Rome. The Hanging Gardens withered along Nebuchadnezzar's empire. They were gone by the time Pliny the Elder visited referred before his death in A.D. 79.

From 539 B.C. to 637 AD, Mesopotamia and the Middle east was ruled by a succession of foreigner usurpers that included the Persian in 539 B.C., Alexander the Great (who died in Babylon in 323 B.C., the Parthians (who ruled for 350 years) and then the Sassanids, Arabs and Turks. Ancient Mesopotamia today lies mostly by Iraq.

Confusion Between Assyrians, Neo-Babylonians and Sadddam Hussein

Juan Luis Montero Fenollós wrote in National Geographic History: It is, perhaps, little surprise that so much confusion surrounds Babylon when texts by Greek and Roman authors often confused Assyrians with Babylonians. When the first-century B.C. writer Diodorus Siculus describes the walls of Babylon, he actually appears to be describing the walls of Nineveh, capital of the Assyrian Empire. He describes a hunting scene that resembles no artwork found on the palaces in Babylon. It does, however, fit descriptions of the hunting reliefs discovered on Assyrian palaces in Nineveh. [Source: Juan Luis Montero Fenollós, National Geographic History, January/February 2017]

This confusion may be due, in part, to the fact that some kings of Assyria, such as Sennacherib (reigned 704-681 B.C.), held the title of king of Babylon. More intriguingly still, a depiction of that Assyrian king found on a bas relief in Nineveh shows leafy gardens watered by an aqueduct. Could it be, then, that the famous gardens were in Nineveh all along?

Inconvenient historical realities have never discouraged rulers from reshaping the history of Babylon in their own image and generating new myths in the process. One of the most brazen examples is not from antiquity, but from the 1980s, when Saddam Hussein — then dictator of Iraq — set out to create a reconstruction of its royal palace. Like his predecessors, he left behind inscriptions on his building projects. On some of the bricks Hussein had inscribed in Arabic: Built by Saddam, son of Nebuchadrezzar, to glorify Iraq.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024