Home | Category: Muslim Art and Architecture / Arab Art

ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE

Kukherd Mausoleum in Iran

Architecture is regarded as one of the greatest Islamic art forms. Muslim architecture is expressed mostly in the form of mosques as well as in related madrassahs (theological schools), khanqahs (monasteries), shrines and mausoleum complexes but is also seen in Muslim houses and gardens. Other kinds of buildings found in the Muslim world include: 1) forts (“arks” ), 2) multi-domed bathhouses (“hammams”), caravanserais (“rabat” covered bazaars (“ tok” ) reservoirs (“hauz” ), ,shopping arcades, hospitals and public fountains.

Zarah Hussain wrote for the BBC: “Some of the typical features are: 1) It's hidden - another term is "the architecture of the veil"; 2) A traditional Islamic house is built around a courtyard, and shows only a wall with no windows to the street outside; 3) It thus protects the family, and family life from the people outside, and the harsh environment of many Islamic lands - it's a private world; 4) Concentration on the interior rather than the outside of a building - the common Islamic courtyard structure provides a space that is both outside, and yet within the building [Source: Zarah Hussain, BBC, June 9, 2009 |::|]

“Another key idea, also used in town planning, is of a sequence of spaces. 1) The mechanical structure of the building is de-emphasised; 2) Buildings do not have a dominant direction; 3) Large traditional houses will often have a complex double structure that allows men to visit without running any risk of meeting the women of the family; 4) Houses often grow as the family grows - they develop according to need, not to a grand design Buildings are often highly decorated and colour is often a key feature. But the decoration is reserved for the inside. Most often the only exterior parts to be decorated will be the entrance and the dome. Religious buildings in particular will often use geometry to symbolic effect. |::|

In pre-Islamic days and the early Islamic period, shrines were built around pilgrimage sites and places of special importance such as the Kaaba, the place where Abraham almost sacrificed Ishmail (the Dome of the Rock) and the tomb of Abraham in Hebron. Later these and the tombs of important Muslim figures became shrines. Mausoleums and shrines are particularly important to Shia and Sufis. Most have a prayer room set under a domed cupola. The actual tombs may be located in a central hall or underground in a crypt-like room. Some have accommodation, washrooms and kitchens.

Books: "Mosque" by David Macaulay (Lorraine Books, Houghtin Mifflin Company. 2003); "The Art and Architecture of Islam, 1250-1800" by Sheila S. Blair (Yale University Press) is first rate book. It is insightful. well written and contains lots of good pictures.

See Separate Article MOSQUES, MOSQUE ARCHITECTURE AND CUSTOMS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Islamic Architecture and Art: Islamic Arts & Architecture /web.archive.org ; Architecture of Islam ne.jp/asahi/arc ; Images of mosques all over the world, from the Aga Khan Documentation Center at MIT dome.mit.edu ; British Museum britishmuseum.org Islamic Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah/hd/orna ; Islamic Art Louvre Louvre ; Museum without Frontiers museumwnf.org ; Victoria & Albert Museum vam.ac.uk ; Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, Qatar mia.org.qa ; CalligraphyIslamic, lots of Islamic calligraphy web.archive.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Islamic Art: Architecture, Painting, Calligraphy, Ceramics, Glass, Carpets” by Luca Mozzati Amazon.com ;

“Islamic Art” by Jonathan Bloom and Sheila Blair Amazon.com ;

“The Art and Architecture of Islam, 1250-1800" by Jonathan Bloom and Sheila S. Blair Amazon.com ;

“Islamic Art and Architecture, 650–1250" by Ettinghausen, Richard, Oleg Grabar, and Marilyn Jenkins-Madina (2001) Amazon.com ;

“Islamic Art and Architecture” by Robert Hillenbrand Amazon.com ;

“The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture (1,400 Years, 500 Color Images) by Moya Carey Amazon.com ;

“Mosque” by David Macaulay Amazon.com ;

“The Mosque: History, Architectural Development & Regional Diversity” by Martin Frishman and Hasan-Uddin Kha Amazon.com ;

“Mosque: Approaches to Art and Architecture” by Idries Trevathan Amazon.com ;

“Mosques: Splendors of Islam” by Leyla Uluhanli, Renata Holod, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Holy Mosques of Makkah & Madinah” by Madiha Ali Amazon.com ;

“The Dome of the Rock” by Oleg Graba Amazon.com

Styles of Muslim Architecture

Yemen

There are two main styles of mosque architecture: 1) hypostyle, in which the roof is supported on pillars: and 2) domical, where the walls are surrounded by a dome. There are few hypostyle mosques and they tend to be old or very basic.

Yemen, Spain-Morocco, India and Central Asia all have own unique architectural styles. The Persian style of architecture was influence by Christian Byzantine styles. Mamluk style is characterized by “ablaq” (red and white bands of stone) and "elaborate carving and patterning around windows and in recessed portals."

Great masterpieces of Islamic architecture include The Prophet's Mosque in Medina, Sulaimaniyeh Mosque in Istanbul, the Taj Mahal in India, the Great Mosque of Damascus, the Great Mosque of Samarra and Alhambra Place in Granada, Spain.

Yemeni architecture is beautiful and unique. Local materials are used—mud brick and reeds in the plains and along wadis and stone in the mountains—that harmonize with surroundings. Decorations on facades varies from region to region. An Italian artist who has lived for a number of years in San’a told AP: “Yemeni architecture is unique. It’s something between architecture and sculpture.”

In the highlands many dwelling are multistory tower houses made from stone, brick or mud, depending on which materials are most readily available. Representing the style of architecture associated with Yemen, they usually have five or six floors. Each house is home to one extended family and each floor is devoted to a specific function. They have been called the world’s oldest skyscrapers.

Ottoman Architecture and Sinan

Ottomans developed the principal of a dome on a square and thin, tall minarets. They built distinctive mosques with a large courtyard, a domed prayer hall with one, two or four long, thin minarets. The rich, elaborate interiors were decorated with colored Iznik tiles with flower design of green, red and blue. Eighteenth century Ottoman architects infused their buildings with baroque adornments.

Suleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul

Mimar Sinan (died 1578), the great and prolific Ottoman architect, is regarded by many as the most influential architect in the Muslim world. Under Suleyman the Great, he designed the Suleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul, several mosques in Edirne, the Khusrawiyya Mosque in Allepo, the Takiyya Complex of buildings in Damascus and reconstructed the Grand Mosque in Mecca.

Sinan was born in a Christian village but rose through the ranks in the Ottoman system under Suleyman the Magnificent. His mosques were famed for their low domes, high minarets and large, well-lighted interior spaces. When Sinan built a mosque, he built the foundation and let it settle for around two years before constructing the rest of the building.

Central Asian Architecture

Central Asia, in particular the cities of Samarkand, Bukhara and Khiva in Uzbekistan, are famous for their architecture. The destructive habits of Genghis Khan, Tamerlane and other nomadic plunderers has meant very little early old stuff remains. Most of the famous architecture in the region dates back to the time of Tamerlane (1336-1405) and the Timurids (Tamerlane and his descendents).

Describing Central Asian Islamic architecture, Philip Glazebrook wrote in Journey to Khiva: “Round the court glistened tiled facades, in every facade is a tiled arch, in the arch a fantastically carved door, every surface writhing with violently-colored patterns of Islam which blaze up like flame, vivid and restless, to end in the suddenly cut-off of the flat-topped wall. Above that the aquamarine domes, beautiful things, in shape and substance serene.”

Important advances that made Central Asia architecture possible included the development of fired bricks in the 10th century, colored timework in the 12th century, polychrome tile in the 14th century and the squinch (a kind or bracketing used in making large domes).

Features and Decorations in Central Asian Buildings

Samarkand's Madrasa Shir Dar

Features associated with the famous Timurid Architecture found in Samarkand and elsewhere in Central Asia include massive blue domes, often ribbed; tile- and mosaic-covered portals (gateway facades); towering, tapering minarets; and courtyards lined with cell-like quarters. The huge entrance portal featured in some buildings, as high as 30 meters, are intended to dwarf all those who stand before Allah.

Mosques, madrasahs and other buildings in Central Asia are famous for their colorful tilework. The tiles not only make the building look beautiful they also make them appear lighter. The tiles are set up to reflect the desert sun. Deep cobalt blue and turquoise (meaning "color of the Turks") were often featured on domes.

In keeping with the Muslim taboo on representations of animals and people, the tiles, walls and arches were decorated with calligraphy, floral designs and geometric shapes. The calligraphy is often either in the stylized kufic script favored by the Timurids or the often filiated thulth scripts.

The tiles come in variety of styles: stamped, chromatic (one color painted on and then fired), polychromatic (several colors painted on and then fired), and faience (carved onto wet clay and then fired). Other decorative features include carved and painted woodwork. patterned brickwork and carved ghanch (alabaster).

Arab Homes

A traditional Arab house is constructed to be enjoyed from the inside not admired from the outside. Often times the only thing that is visible from the outside are walls and a door. In this way the house is hidden, a condition described as "the architecture of the veil"; By contrast Western houses faces outwards and have big windows. Traditionally, most Arab houses were built from materials at hand: usually brick, mud brick or stone. Wood was usually in short supply.

Arab houses have traditionally been designed to be cool, and well shaded in the summer. The ceilings were often vaulted to prevent humidity. In the ceiling and roof were various devices including pipes that aided ventilation and carried in breezes and circulated them around the house.

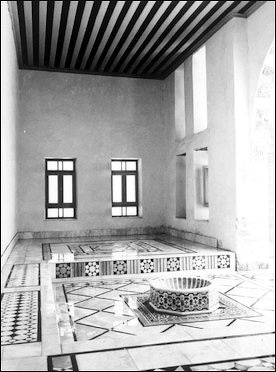

typical Arab house

Traditional homes are often organized around separate areas for men and women and places the family welcomed visitors. They are built for an extended family. Some are organized so that people live in shady rooms around the courtyard in the summer then move to paneled first floor rooms, filled with oriental carpets, in the winter. Homew of the wealthy in the Middle East have living spaces and walkways that radiate asymmetrically from the inner courtyard.

Arthur Goldschmidt, Jr. wrote in “A Concise History of the Middle East”: In the early Islamic period “houses were constructed from whatever type of building material was locally most plentiful: stone, mud brick, or sometimes wood. High ceilings and windows helped provide ventilation in hot weather; and in the winter, only warm clothing, hot food, and an occasional charcoal brazier made indoor life bearable. Many houses were built around courtyards containing gardens and fountains.” [Source: Arthur Goldschmidt, Jr., “A Concise History of the Middle East,” Chapter. 8: Islamic Civilization, 1979, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

Courtyards and the Organization of an Arab Home

A traditional Arab house is built around a courtyard and sealed off from the street on the ground floor except for a single door. The courtyard contains gardens, sitting areas and sometimes a central fountain. Around the courtyard are rooms that opened onto the courtyard. Multi-story dwellings had stables for animals on the bottom floor and quarters for people and grain storage areas on the upper floors.

Zarah Hussain wrote for the BBC: A traditional Islamic house is built around a courtyard, and shows only a wall with no windows to the street outside; It thus protects the family, and family life from the people outside, and the harsh environment of many Islamic lands - it's a private world; Concentration on the interior rather than the outside of a building - the common Islamic courtyard structure provides a space that is both outside, and yet within the building [Source: Zarah Hussain, BBC, June 9, 2009 |::|]

“Another key idea, also used in town planning, is of a sequence of spaces. 1) The mechanical structure of the building is de-emphasised; 2) Buildings do not have a dominant direction; 3) Large traditional houses will often have a complex double structure that allows men to visit without running any risk of meeting the women of the family; 4) Houses often grow as the family grows - they develop according to need, not to a grand design |::|

Courtyard House in Ottoman-Period Damascus

On a courtyard house in Ottoman-Period Damascus, Ellen Kenney of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “One entered the Damascene courtyard house from a plain door on the street into a narrow passage, often turning a corner. This bent-corridor arrangement (dihliz) provided privacy, by preventing passers-by in the street from viewing the interior of the residence. The passage led to an internal open-air courtyard surrounded by living spaces, usually occupying two floors and covered with flat roofs. Most well-to-do residents had at least two courtyards: an outer court, referred to in historical sources as the barrani, and an inner court, known as the jawwani. An especially grand house might have had as many as four courtyards, with one dedicated as the servants' quarters or designated by function as the kitchen yard. These courtyard houses traditionally housed an extended family, often consisting of three generations, as well as the owner's domestic servants. To accommodate a growing household, an owner might enlarge the house by annexing a neighboring courtyard; in lean times, an extra courtyard could be sold off, contracting the area of the house. [Source: Ellen Kenney, Department of Islamic Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Kenney, Ellen. "The Damascus Room", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2011, metmuseum.org \^/]

Maktab Anbar in Damascus

“Almost all courtyards included a fountain fed by the network of underground channels that had watered the city since antiquity. Traditionally, they were planted with fruit trees and rosebushes, and were often populated by caged song-birds. The interior position of these courtyards insulated them from the dust and noise of the street outside, while the splashing water inside cooled the air and provided a pleasant sound. The characteristic polychrome masonry of the walls of the courtyard's first story and pavement, sometimes supplemented by panels of marble revetment or colorful paste-work designs inlaid into stone, provided a lively contrast to the understated building exteriors. The fenestration of Damascus courtyard houses was also inwardly focused: very few windows opened in the direction of the street; rather, windows and sometimes balconies were arranged around the walls of the courtyard (93.26.3,4). The transition from the relatively austere street façade, through the dark and narrow passage, into the sun-splashed and lushly planted courtyard made an impression on those foreign visitors fortunate enough to gain access to private homes - one 19th century European visitor aptly described the juxtaposition as "a gold kernel in a husk of clay."

“The courtyards of Damascus houses typically contained two types of reception spaces: the iwan and the qa'a. In the summer months, guests were invited into the iwan, a three-sided hall that was open to the courtyard. Usually this hall reached double-height with an arched profile on the courtyard façade and was situated on the south side of the court facing north, where it would remain relatively shaded. In the winter time, guests were received in the qa'a, an interior chamber usually built on the north side of the court, where it would be warmed by its southern exposure.” \^/

Rooms and Features of Arab Homes

Arthur Goldschmidt, Jr. wrote in “A Concise History of the Middle East”: “Rooms were not filled with furniture; people were used to sitting cross-legged on carpets or very low platforms. Mattresses and other bedding would be unrolled when people were ready to sleep and put away after they got up. In houses of people who were reasonably well-off, cooking facilities were often in a separate enclosure. Privies always were.” [Source: Arthur Goldschmidt, Jr., “A Concise History of the Middle East,” Chapter. 8: Islamic Civilization, 1979, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

In many Arab homes people like to eat and hang out on the floor

Houses used by Muslims often have separate areas for men and women. In bedrooms, Muslims don't want their feet pointing towards Mecca. In some places people sleep on the roof of their house at night and retreat to the cellar for an afternoon nap. The main reception area has the best views and caught the coolest breezes.

Windows and wooden shudders or latticed woodwork are known as “ mashrabiyya”. Ceilings, interior walls, basements and doors are often elaborately decorated. Walls are stuccoed with floral designs and stone was used to construct works of calligraphy or floral motifs. Wood was a symbol of wealth.

Zarah Hussain wrote for the BBC: “Buildings are often highly decorated and colour is often a key feature. But the decoration is reserved for the inside. Most often the only exterior parts to be decorated will be the entrance.” Thick doors hung with heavy iron knockers in the shape of a hands, the hand of Fatima, the Prophet’s daughter, lead to sunny patios, sometimes with fountains.

In poor areas the toilets are often Asian-style squat toilets that are often little more than a hole in the ground. In nice homes and hotels, Western-style toilets often have a bidet, a contraption that looks like a combination sink and toilet is used for washing the butt.

Room in Ottoman-Period Courtyard House in Damascus

“On a residential reception chamber (qa'a) in a late Ottoman courtyard house in Damascus, Ellen Kenney of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The highlight of the room is the splendid decorated woodwork installed on its ceiling and walls. Almost all of these wooden elements originally came from the same room. However, the exact residence to which this room belonged is unknown. Nevertheless, the panels themselves reveal a great deal of information about their original context. An inscription dates the woodwork to A.H. 1119/1707 A.D, and only a few replacement panels have been added at later dates. The large scale of the room and the refinement of its decoration suggest that it belonged to the house of an important and affluent family. [Source: Ellen Kenney, Department of Islamic Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Kenney, Ellen. "The Damascus Room", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2011, metmuseum.org \^/]

Many upper class houses have sitting rooms with chairs and tables

“Judging from the layout of the wooden elements, the museum's room functioned as a qa'a. Like most Ottoman-period qa'as in Damascus, the room is divided into two areas: a small antechamber ('ataba), and a raised square seating area (tazar). Distributed around the room and integrated within the wall paneling are several niches with shelves, cupboards, shuttered window bays, a pair of entrance doors and a large decorated niche (masab), all crowned by a concave cornice. The furnishing in these rooms was typically spare: the raised area was usually covered with carpets and lined with a low sofa and cushions. When visiting such a room, one left one's shoes in the antechamber, and then ascended the step under the archway into the reception zone. Seated on the sofa, one was attended by household servants bearing trays of coffee and other refreshments, water pipes, incense burners or braziers, items that were generally kept stored on shelves in the antechamber. Typically, the shelves of the raised area displayed a range of the owner's prized possessions - such as ceramics, glass objects or books - while the cupboards traditionally contained textiles and cushions.\^/

“Ordinarily, the windows facing the courtyard were fitted with grills as they are here, but not glass. Shutters snugly mounted within the window niche could be adjusted to control the sunlight and airflow. The upper plastered wall is pierced with decorative clerestory windows of plaster with stained glass. At the corners, wooden muqarnas squinches transition from the plaster zone to the ceiling. The 'ataba ceiling is composed of beams and coffers, and is framed by a muqarnas cornice. A wide arch separates it from the tazar ceiling, which consists of a central diagonal grid surrounded by a series of borders and framed by a concave cornice.\^/

“In a decorative technique very characteristic of Ottoman Syria known as 'ajami, the woodwork is covered with elaborate designs that are not only densely patterned, but also richly textured. Some design elements were executed in relief, by applying a thick gesso to the wood. In some areas, the contours of this relief-work were highlighted by the application of tin leaf, upon which tinted glazes were painted, resulting in a colorful and radiant glow. For other elements, gold leaf was applied, creating even more brilliant passages. By contrast, some parts of the decoration were executed in egg tempera paint on the wood, resulting in a matte surface. The character of these surfaces would have constantly shifted with the movement of light, by day streaming in from the courtyard windows and filtering through the stained glass above, and by night flickering from candles or lamps.\^/

room inside Maktab Anber from Ottoman-Era Damascus

“The decorative program of the designs depicted in this 'ajami technique closely reflects the fashions popular in eighteenth-century Istanbul interiors, with an emphasis on motifs such as flower-filled vases and overflowing fruit-bowls. Prominently displayed along the wall panels, their cornice and the tazar ceiling cornice are calligraphic panels. These panels bear poetry verses based on an extended garden metaphor - especially apt in conjunction with the surrounding floral imagery - that leads into praises of the Prophet Muhammad, the strength of the house, and the virtues of its anonymous owner, and concludes in an inscription panel above the masab, containing the date of the woodwork.\^/

“Although most of the woodwork elements date to the early eighteenth century, some elements reflect changes over time in its original historical context, as well as adaptations to its museum setting. The most dramatic change has been the darkening of the layers of varnish that were applied periodically while the room was in situ, which now obscure the brilliance of the original palette and the nuance of the decoration. It was customary for wealthy Damascene home-owners to refurbish important reception rooms periodically, and some parts of the room belong to restorations of the later 18th and early 19th centuries, reflecting the shifting tastes of Damascene interior decoration: for example, the cupboard doors on the south wall of the tazar bear architectural vignettes in the "Turkish Rococo" style, along with cornucopia motifs and large, heavily gilded calligraphic medallions.\^/

“Other elements in the room relate to the pastiche of its museum installation. The square marble panels with red and white geometric patterns on the tazar floor as well as the opus sectile riser of the step leading up to the seating area actually originate from another Damascus residence, and date to the late 18th or 19th century. On the other hand, the 'ataba fountain may pre-date the woodwork, and the whether it came from the same reception room as the woodwork is uncertain. The tile ensemble on the back of the masab niche was selected from the Museum collection and incorporated in the 1970s installation of the room. In 2008, the room was dismantled from its previous location near the entrance of the Islamic Art galleries, so that it could be re-installed in a zone within the suite of new galleries devoted to Ottoman art. De-installation presented an opportunity for in-depth study and conservation of its elements. The 1970s installation was known as the "Nur al-Din" room, because that name appeared in some of the documents related to its sale. Research indicates that "Nur al-Din" probably referred not to a former owner but to a building near the house that was named after the famous twelfth-century ruler, Nur al-Din Zengi or his tomb. This name has been replaced by "Damascus Room" – a title that better reflects the room's unspecified provenance.”\^/

Madrasahs

courtyard of Shir Dar madrassah in Samarkand

Many of the most famous Islamic buildings are madrassahs (madrasahs), Islamic theological schools. They typically are two stores high and have a central courtyard surrounded by cell-like living quarters ( hujras ) used by students, teachers and traveling scholars.

Madrasahs and the square in front of them were often the central building of a Central Asian city the same way a cathedral and market square were at the center of European cities. Markets were often set up in the squares in front of madrasahs and the niches in front wall of the madrasah were used by merchants.

The main features are the monumental portal at the entrance, a mosque to the right of the entrance, a lecture hall to the right, and arched portals in the central courtyard. These days the cells in the courtyards are often filled with carpet sellers and souvenir shops.

Hammams

Hammans (Turkish baths, hamam) and public baths are a vestige of Ottoman bath culture. They are common in Arab countries because a premium is put on cleanliness and running water in homes has traditionally been in short supply. Hammams traditionally have consisted of sunken tubs and marble platforms surrounded by glazed tiles, all placed in rooms without windows, which trapped heat and moisture from a Turkish steam bath. Large hamans traditionally have had a central tub with marble steps. Some have enclosed private tubs. The steam is relaxing and hot but not as hot as a sauna. Nice hammams have domes above the tubs and marble slabs. The domes often have small holes in them through which beams of light strike the bather.

Hammams are found in most Muslim countries. Islam emphasizes cleanliness and washing, particularly before prayer. But on top of their original religious function they were also places for people to relax and socialize. “It is not just about bathing. It is a purification process, a ritual process,” Tevfik Ilter, an architect involved in the restoration of old hammams in Istanbul, told Reuters. [Source: Alexandra Hudson, Ece Toksabay, Reuters, June 1, 2011]

Hammam in Kosovo

Mary Ellen Monahan wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “The Turkish hamam, descendant of the baths of ancient Rome and Byzantium, is the site of one of the world's great bathing rituals — a place not just to get clean (Islam, like many religions, links physical and spiritual purity) but also to recharge and relax, alone or with friends. Once upon a time, the Ottoman Empire's thousands of hamams marked important ceremonies such as births and weddings. These days, it's more of a social ritual than a necessity with the spread of indoor plumbing in the last century.” [Source: Mary Ellen Monahan, Los Angeles Times, November 1, 2013]

There are hammams for both men and women. Some Turkish baths have separate baths for men and women. Others have certain hours of the day when each sex is admitted. Women generally have the afternoons and the men the evenings. They were traditionally places where people gathered to socialize, gossip and exchange news.

Hamman means "spreader of warmth." The custom of taking Turkish-style baths goes back centuries before the Ottoman Turks. Not as elaborate as their Roman counterparts, medieval hammans featured a series of rooms heated at different temperatures. Cleanliness was prized but was a luxury in the hot climates. A link was made between cleanliness, purity and spirituality. It is said that Crusaders who enjoyed hammams in the Holy Land brought the custom back to Europe.

See Separate Article on Hammams

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, Encyclopedia.com, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The Conversation, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, Al Jazeera, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Library of Congress and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024