Home | Category: Arab Food and Drink

NON-ALCOHOLIC DRINKS IN THE MIDDLE EAST

jellab

Middle Easterners and Arabs are big tea and coffee drinkers. Other common non-alcoholic drinks include “aryan” (yoghurt drink), “limonada” (lemonade), “loomey” (sweet lime juice), and “jellab” (a drink made with raisins and served with pine nuts). In some places you can get freshly-squeezed sugar cane juice, fresh-squeezed orange drink, coconut drink, and sweet tamarind drink. In Morocco you can also get “halib luz” (almonds and milk) and “judor” (lightly sweetened lemonade), Small stands that sell fruit drinks. Coke, Pepsi and Fanta are widely available. The tap water is safe in fancy hotels but otherwise should be regarded with suspicion. Bottled water often comes in two varieties: with gas and without gas. Restaurants generally don't serve water, and if they do be careful about drinking it.

One of weirdest drink I tried in Turkey was barley soda pop. It tastes like flat non-alcoholic Guinness Stout. All restaurants, stores and snack bars sell “aryan” (a watered-down yogurt drink), the traditional drink of Turkish shepherds. On ferries in Istanbul you can get a sweet drink called “solup” (salep) that is made with a spice that sells for the same price per ounce as good hashish. Solup is made from wild orchid tubers ground to the gritty texture of fine cream of wheat. In the winter it mixed with sugar and milk and served as a hot, thick drink.

In Istanbul and other places you can find drink sellers in colorful embroidered and tasseled costumes and spats with huge brass samovar-like dispensers strapped to their backs. They usually serve sour cherry juice or some other fruit juice in small paper cups. Popular drinks sold by vendors on the streets include boiled beans served in a glass and “boz”, a mildly alcoholic drink, originally from Albania, made from wheat berries.

In Iran, many restaurants, stores and snack bars sell “doogh “(a watered-down yogurt beverage yogurt drink similar to Turkish “aryan”). “Sherbat” is a drink made with sugar and crushed berries or fruit. “Palouden”, a rose-flavored ice drink with a lemon juice, is a specialty of Shiraz. Pomegranate juice, mango juice, and sweetened water are also available.

Websites and Resources: Arabs: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Who Is an Arab? africa.upenn.edu ; Encyclopædia Britannica article britannica.com ; Arab Cultural Awareness fas.org/irp/agency/army ; Arab Cultural Center arabculturalcenter.org ; 'Face' Among the Arabs, CIA cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence ; Arab American Institute aaiusa.org/arts-and-culture ; Introduction to the Arabic Language al-bab.com/arabic-language ; Wikipedia article on the Arabic language Wikipedia ;

Sharia (Islamic Law): Oxford Dictionary of Islam oxfordislamicstudies.com ; Encyclopædia Britannica britannica.com ; Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Sharia by Knut S. Vikør, Oxford Encyclopedia of Islam and Politics web.archive.org ; Law by Norman Calder, Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World oxfordislamicstudies.com ; Sharia Law in the International Legal Sphere – Yale University web.archive.org ; 'Recognizing Sharia' in Britain, anthropologist John R. Bowen discusses Britain's sharia courts bostonreview.net ; "The Reward of the Omnipotent" late 19th Arabic manuscript about Sharia wdl.org

Soft Drinks in the Middle East

Coca-Cola was banned in much of the Arab world because it was sold in Israel. Muslims are told not to drink Coca-Cola because, it is said, the name when reflected in a mirror forms the Arabic words “No Muhammad, No Mecca.” At one time Pepsi was the favorite drink of Iraqis.

Mecca cola is a soft drink produced in the United Arab Emirates that touts itself as the Islamic alternative to Western soft drinks. Its sales tripled after the controversy revolving around the publication of the cartoons in a Danish newspaper that portrayed the Muhammad in a bomb-shaped turban. The biggest markets for the drink are in Malaysia, Algeria, Yemen and France. The soft drink maker also makes a energy drink called Mecca Power sold under the slogan “Get the Halal Power.”

Iran produces its own orange, lemon and cola drinks: Noushab, Parsi and Zamzam. You can also get soft drinks like Coke, Pepsi, and Fanta but they cost about 10 times as much as the Iranian imitations of these drinks.

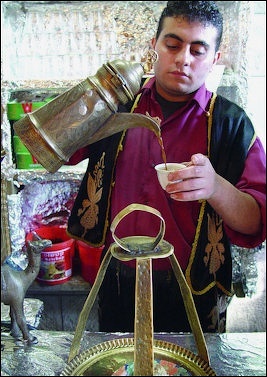

Turkish Coffee and Coffee in the Middle East

preparing Turkish coffee

Middle Easterners favor Turkish-style coffee, which is similar to espresso: gritty, strong and served in little cups. Some people drink it very sweet. It is often flavored with cardamom. Don’t drink the last little bit unless you want a mouth full of grit. In some place it seems like men spend the whole day drinking coffee or tea and smoking water pipes. When people ask for coffee at restaurants there are usually given “Nescafe” instant coffee.

Middle-Eastern-style coffee is prepared from heavily roasted beans ground into a fine powder. From this is prepared a thick, black fluid which is drunk grounds and all. “ Bedouin kahwa” is a strong aromatic coffee with cardamon powder, saffron and rosewater. Cardamom can simply be added to the coffee powder . Some Bedouin coffee pots have several cardamon capsules in their spouts.

Many Saudis drink their coffee very sweet. It is often flavored with cardamom and prepared in a brass coffee pot with a long spout. At social occasions coffee is often followed by a glass of mint tea. In some places in the Persian Gulf people drink traditional green coffee, which is very bitter and served in little cups.

Turkish coffee is made with coffee is like regular coffee. The main difference is that the coffee is ground very fine so that it has the consistency of flour. The water, just before it boils, is poured through grounds in a strainer. With traditional Turkish coffee, the beans are ground with a mortar and pestle rather than a mill. Boiling water is poured over the grounds through a silver sieve into a pot. This is brought to a boil and poured through a sieve again and then served.

Early History of Coffee

Coffee originates came from Kaff province of Ethiopia, the source of the name coffee. According to legend, it was discovered in A.D. 850 by a goat herder named Kaldi, who noticed how lively his flock became after munching red beans from a coffee plant and then tried some himself and became as upbeat as his goats.

In the early days of coffee, people simply chewed the berries. Many years passed before someone thought of making a drink from them. Arab trader decided to boil the coffee beans they got from Ethiopia.

Around A.D. 1000 the first cup of coffee, or "bean broth," was prepared in Yemen, across the Red Sea from Ethiopia, where coffee was grown in the mountains. The drink became popular throughout teetotaling Muslim world and became known as the “the wine of Araby.” Before long mullahs were complaining that their followers were spending more drinking coffee than were praising Allah.

Raw coffee doesn't brew into anything pleasant. In the 13th century, someone decided to roast the berries, which releases a pungent oil that produce the familiar coffee aroma, The first recorded consumption of coffee as we know it today took place in the 15th century by Sufi mystics who used the drink in their rituals

Coffee and Turkey

Turkish coffee

Coffee was introduced to Europe from Turkey. Coffee originated in Ethiopia and was introduced to the Ottoman empire from Yemen. The Ottomans in turn introduced it to Europe. The Ottoman empire took over the coffee trade when they took over Yemen. The oldest known coffee houses were opened in Constantinople in 1554 by two merchants. As well as places to hang out they were became known as "schools of the cultured." These coffee houses were ultimately closed for stimulating social dissent. At this time Al-Makha (Mocha) in Yemen was the focal point of the coffee trade.

Turkish coffee became so popular in Istanbul that women were allowed to divorce their husbands if they couldn't keep the “ ibrik”, or pot, filled. Turkey never grew its own coffee, and the drink was popular only when the Ottoman empire was rich enough to import large quantities of beans. Turkish soldiers drank it as the besieged Vienna in 1683.

The Ottomans in turn introduced coffee to Europe. Venetians merchants carried the first cargo of coffee from Turkey to Italy in the late 16th century. By 1618, the English and Dutch had set up coffee factories in Al-Makha (Mocha) in Yemen and made a killing when coffee houses became all the rage in the late 1600s.

The first coffee houses opened in Venice and Amsterdam in the 1630s. Coffee was introduced to France during the court of Louis XIV by a Turkish ambassador in 1669 The world's first café was opened on a street called rue de l'Ancienne Comédie Paris in 1686 by a Sicilian named Francisco Propio, who sold coffee as well as fruits syrups, tea, liqueurs, chocolate, “ glaces” (proto-ice-cream). By the 1723, there were 300 cafés in Paris and 800 by 1800.

The Catholic church initially denounced coffee as the drink of infidels, but later, according to one story, baptized it and gave it Christian status because Pope Clement liked the drink so much he felt it would be a shame if it remained solely in the hands of Muslim infidels. Yemen and Al-Makha had a monopoly in the coffee trade until the 18th century when some coffee plants were smuggled out and used to establish a plantation in Ceylon.

Tea in the Middle East

Sweet, sugary tea is also popular. It is often served in very hot glasses that are hard to handle. The easiest way to drink from them is to hold the bottom with your thumb and the top with your forefinger. In places such as Lebanon and Afghanistan, green tea is favored. Mint tea is popular in some places. In Iran, pomegranate tea is regarded as “good for the blood.” Water or tea is usually served with a meal. Mint tea is often offered when the meal is over. Shops try to lure in foreign customers by offering them a glass of tea.

Middle Eastern-style tea

Turks are big tea drinkers. It seems Turks always have a small tulip-shaped glass of tea in their hand and sidewalks teem with servants and waiters delivering tea to patrons in shops and clients at business meeting. Usually, tea is served with two lumps of sugar, and Turks prefer glasses with saucers to cups, even though the glasses are often too hot to hold. To keep your hand from burning hold the glass with at the rim. In some places, particularly those frequented by Britons, milk is offered with tea. You can also get pomegranate tea, which is regarded as “good for the blood.”

Istanbulers drink tea around the clock and I wouldn't be surprised if some Turks drank forty or more glasses a day. The average Turk consumes 2.5 kilos of tea leaves each year (tied with Britain for the world's number one position). The Turkish population drink 139,000 tons of tea annually (the world's forth highest rate of consumption behind India, China and Britain). Much of the tea consumed in Turkey is produced in the country: in the mountains near the Black Sea in northeast Turkey.

Egyptians drink heavily sugared hot tea from glasses. In Iran small glasses of tea are served at most social and business gathering. Iranian tea is very strong and served piping hot with sugar, which some people put in their tea and others stick in their mouth and suck tea through it. Many drink endless cups of tea at tea houses, many of which also offer water pipes. As rule milk isn’t offered with tea. Omanis like tea flavored with mint, cloves, cardamon or cinnamon. In Iraq, tea is dark, very sweet and served in half-filled glasses. There is a tinkling sound made when the sugar is mixed in the glass. Small glasses of tea are served at most social and business gathering. Iraqi tea is often very sweet and/or flavored with cardamom and is served piping hot. In Tunisia sweet, sugary tea is often spiced with mint and sometimes with pine nuts,

Throughout the Middle East, tea is served in Turkish-style tulip glasses with two lumps of sugar. Many Middle Easterners like to drink hot tea is the summer as a relief from the heat. The reasoning goes that the hot tea causes your pores to open up, increasing the sweat flow, thereby cooing you off. Lipton is marketing very heavily in some places.

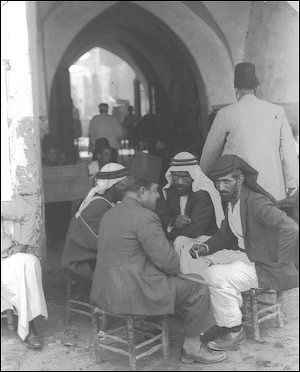

Drinking Customs in the Muslim-Arab World

Palestine coffee house

Muslim law and tradition even describe how a person should drink tea: three slow sips, not blowing on the tea, but waiting for it to cool naturally. Sometimes tea is spilled into a saucer to symbolize generosity of a host. By custom, Arabs generally don’t drink more than three cups of coffee at one time. If you are nervous about drinking the water, politely ask for a soft drink or tea.

The “farash” system depends on a server who brings coffee or tea to people in their office or shop. He often has an office and is summoned by a buzzer. When tea or coffee is finished it should be given back to the server. It is considered rude to put it on a table because the cup or glass may be refilled and given to someone else. [Source: “Middle East and North African Customs and Manners” by Elizabeth Devine and Nancy Braganti (St. Martin’s Press)]

In Morocco, tea is often served following a special ritual: 1) a pot is cleaned with boiling water; 2) green tea and sugar and hot water are boiled; 3) more water, sugar and mint are added; 4) the mixture is poured in a glass and back into the pot; 5) when the tea is ready it is poured from high in the air so that a ring of bubbles—called a “fez”—forms around the rim of the glass. If there is no fez the tea is not regarded as properly prepared.

Tea Houses, Coffee Shops and Socializing

Socializing among men often revolves around smoking and drinking tea. Cigarettes are offered as a sign of hospitality and friendship. If you have cigarettes you are expected to offer them to others. It is considered somewhat impolite to refuse a cigarette but these days most Arabs realize that smoking is frowned upon in the West and accept a refusal by foreigners.

Most bars, coffee houses, tea houses, and even restaurants in Turkey and the Middle East are male-only establishments; a women entering one of these places is received the same way she would if she entered the men's rest room. Coffee shops and tea houses are often filled with smokers. It is customary to lay a pack of cigarettes on a table next to one’s cell phone and thick coffee or glass of tea.

Turkish men spend a lot of time in kahvehanes (tea houses), chatting and playing games such as Turkish poker (using only three cards), backgammon or okay, a game similar to dominoes. Whenever men play these games they seem to particularly enjoy slapping the pieces or cards as hard as they can on the table. Teahouses are called “chaikhana” in Iraq.

“Keyif” is Turkish word that is used to described the pleasure one gets at hanging out at a restaurant or tea house for hour after hour, socializing, drinking tea, coffee or raki, enjoying the company of good friends and perhaps playing backgammon and cards. Some Americans view this same behavior as wasting time.

Roadside Coffee Shop in Jordan

Old Arab Tea House in Bagamoyo, Tanzania

Reporting from a coffee shop next to a highway near Amman, Anthony Shadid wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “With motions made routine by practice, Aziz Suwair poured a heaping spoon of powdery coffee into a long-handled pot of scalding water. He stirred, then danced it on a flame like a marionette. By a conservative estimate, he has gone through these motions 600,000 times. As he worked, the clouds finally parted, ending a winter rain that has turned the arid bluffs over the Jordan Valley into rolling green hills. By 11am, the sun began to arch overhead, on a Friday — the traditional day of rest. But Suwair, in his roadside shack, serving coffee to the drivers of farm trucks, passenger buses, police cars and taxis, was just a little into a day that stretches from dawn to midnight. "For six years," he said, with a hint of a smile, "I haven't moved from this place." [Source: Anthony Shadid, Los Angeles Times-Washington Post, May 31, 2007 +++]

“When he was 20, Suwair hauled two battered cabinets, painted red and blue, to the shoulder of the well-travelled highway that ties the Jordanian capital, Amman, to the Dead Sea. He propped them on cinder blocks, now fastened to the dirt by time. He slung a burlap sack overhead, where it shares space with cardboard and tattered upholstery in a floral pattern of green and yellow. Almost every day since then, he has tended a tea kettle and a charred coffee pot on a stove, fed by a butane tank, with spare fuel under the rusting cabinet. Scattered near the cinder blocks are his jerrycans of water, drawn from the Adasiyya Spring, a short walk away. "Aziz's Shopping Mall," he declared, with a mix of grandiosity and self-deprecation. But he takes his business very seriously. "My coffee is peerless," he insisted. "Like a cappuccino." +++

“Suwair's rickety shop is along a bend in the road, about 10 miles west of Amman. On one side are verdant bluffs, punctuated by trees of olives and pine. On the other are the rock-studded valleys known as wadis, a gentle, ancient landscape. A little above, patches of snow linger from a storm the night before. "God give you strength," Suwair shouted out at noon as a customer, Ahmad Ali, pulled up in a yellow taxi. "That is my cousin," he said, a name Suwair gives to anyone from his family's village of Ajram. +++

coffee house in Jerusalem

“Suwair estimates that he makes 300 cups of coffee a day, along with 50 cups of tea. Coffee sells for 30 cents, tea half of that. With each, he brings a flair that suggests art. A flick of the wrist puts the water into the kettle, another pours in the coffee, ground to his specification. It boils, with a slight froth, and he pours a little into a plastic cup. He lets it boil again, then pours again. The sugar depends on the customer — plain, medium or sweet. He goes through nearly seven pounds of coffee a day and twice as much sugar. By early afternoon, a few vehicles were waiting for him on the shoulder — trucks carrying sand to build the villas and offices in Amman, pickups laden with tomatoes from the fertile Jordan Valley, taxis carrying tourists to Dead Sea resorts. "This road stays alive 24 hours a day," he said.” +++

More trucks, cars and pickups pulled over. Faisal Adwan told him to say hello to his father. A policeman parked, kissing Suwair on both cheeks and receiving a cup of coffee for free. Other vehicles honked, drawing a wave from Suwair. Then came Mohammad Adnan Shilbaya, his pickup filled with bags of discarded cans, bound for a recycling shop in Amman. "He is the best one," Shilbaya said, sipping his coffee and smoking a cigarette. "I am telling you the truth." Suwair laughed. "All I can do is write those words on a snowflake," he said. "When the sun comes, they will be gone." Shilbaya left and then Suwair took a break. It was 2pm and he dragged easily on a cigarette. "No one is my boss," he said. "No one is over my head. I want to ask you," he went on. "Is it better to sit on top of this hill, by yourself, looking out at the view?" He pointed to a valley along the nearby salt mountains. "Or is better to be in the middle of a crowd of people?" He wasn't waiting for an answer.” +++

Socializing and Sharing Tea and Smokes in a Cairo Barber Shop

Traditionally men liked to gather in the shade of tents and the aroma of incense, sharing tea, coffee and fruit while conversing about camels and issues of the day. These days they like to gather in tea shops, coffee shops, hookah-smooking rooms and barber shops

Daniel Williams wrote in the Washington Post, “It was 11:30 at night, and the Professeur Barber Shop on narrow Um ul-Ghulam Street in a run-down section of Cairo was running at full capacity. Three young barbers offered haircuts, shaves, facials and flattery to customers who filled a trio of threadbare chairs and stools that lined the tiny establishment. Sayeed, a barber who had dyed his hair copper and moussed it into little waves that lapped merrily about the top of his head, waved a razor in one hand and a cigarette in the other over a client. It seemed a dangerous moment, but nothing compared with what followed. [Source: Daniel Williams, Washington Post, May 2, 2006 ^~^]

“As a bouncy tune by the Egyptian singer Tamer Hosni blared from a boombox tucked among towels and a Qur’an in a corner of the shop, Sayeed undulated and lip-synched the words that told something about the arrival and departure of a girl. It looked like he was doing a saber dance. The customer closed his eyes -- whether to avoid looking at the tiny torch and sharp instrument that Sayeed brandished inches from his nose or just to relax in anticipation of the razor's next stroke, it was hard to say. ^~^

reading coffee grounds, a popular form of fortunetelling in Turkey

“Lots of things go on besides barbering at the Professeur. The shop got its name from a customer who once complimented the workers there as masters of their craft, which in Egypt can be expressed by calling them professeurs, an example of lingering French influence. A night at the Professeur — the coolness after dark contrasts pleasurably with the motionless heat of Um ul-Ghulam in daytime — is an opportunity to sing, gossip, sip tea or coffee and smoke from a shisha, the Egyptian water pipe filled with slow-burning tobacco. ^~^

“The tangle of activities and conditions would seem incompatible with haircuts — smoke blown in eyes, music that drowns out conversation, electric cables that twist around tubes emanating from the water pipe, boys who bring in hot refreshments and dart under the elbows of the barbers. The shop's decor adds to the feeling that at the Professeur anything goes: fluorescent lighting, little red Chinese lanterns, plastic plants, Christmas tinsel, posters of singers and models, Egyptian talismans to ward off envy and evil, and carved plaques with Qur’anic verses that describe the rewards of praising Muhammad and the promise of protection to the righteous. On this night, a cockroach navigated tufts of hair on the floor. And the barbers keep the mood light.” ^~^

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994). “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, BBC, Al Jazeera, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018