ASSYRIAN CITIES

Ashur

The Assyrians built some of the first planned cities. The first Assyrian city was Ashur. Great Assyrian cities included of Nimrud (Biblical Calah), Khorsabad and Nineveh (See Below). Assyrian ships carried grain, wood, stone, leather and wine up and down the Tigris River and docked on the river’s massive quays. Some Assyrian cities had sewage systems but garbage appears to have been thrown in the streets anyway.

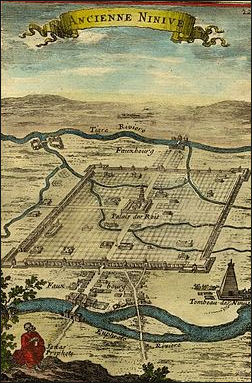

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: Throughout their history, which goes back to around 2600 B.C., the Assyrians had built a succession of capital cities, beginning with Ashur, then Kalkhu, the ancient name for Nimrud, and then Dur-Sharrukin. After his father’s death, Sennacherib resolved to create yet another new capital. “Sargon II dies ignominiously in battle and so [his capital] Khorsabad is considered a bad luck place, and his son is having none of this,” says archaeologist Michael Danti of the University of Pennsylvania. Sennacherib would follow in his father’s footsteps as a builder. In the new capital, which was located 10 miles south of Dur-Sharrukin and was twice as large, the palaces were even bigger, the artwork grander, and the walls taller. In the Old Testament, it was a notorious place of avarice and indulgence. In Greek and Roman sources, it was described as a legendary site of unparalleled size and riches. This was Nineveh. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, Features July/August 2024]

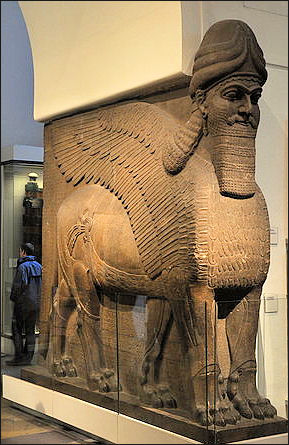

Dur Sharrukin (near Nineveh) was the fourth capital of Assyria. Also known as Khorsabad, it is the home of a palace of Sargon II (reigned 721-705 B.C.). Monumental sculptures found here were have been put on display in Baghdad and Paris. In the 1990s, a magnificent human-headed winged bull was found here. The ancient city was excavated by an archaeological team from the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute. See looters, Iraq

Dur-Sharrukin was intended to be the greatest city of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which, in the late eighth century B.C., became the largest the world had known. The city was built by Sargon II (reigned 721–705 B.C.)—the name Dur-Sharrukin means “fortress of Sargon”—to be the new capital of his flourishing kingdom. The king constructed lavish palaces, ornate temples, and mighty defensive walls. His splendid city, however, was short-lived. In 705 B.C., just a decade after he founded Dur-Sharrukin, while the city was still being built, Sargon died on the battlefield. His son Sennacherib (reigned 704–681 B.C.) inherited the throne and soon abandoned his father’s project.

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Assyrian Empire's Capitals: The History and Legacy of Nineveh, Assur, and Nimrud” by Charles River Editors and Colin Fluxman Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Near East (Volume II): A New Anthology of Texts and Pictures”

by James B. Pritchard (1976) Amazon.com;

“Nimrud - An Assyrian Imperial City Revealed” by David Oates and Joan Oates (2001) Amazon.com;

“Nimrud: The Queens' Tombs” by Muzahim Mahmoud Hussein, McGuire Gibson (2016) Amazon.com;

“Cuneiform Texts from Nimrud: Volume VI - Documents from the Nabu Temple and from Private Houses on the Citadel” by S Herbordt, R Mattila, et al. (2025) Amazon.com;

“Nineveh and Babylon” by Austen Henry Layard Amazon.com;

“Winged Bull: The Extraordinary Life of Henry Layard, the Adventurer Who Discovered the Lost City of Nineveh” by Jeff Pearce (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Land of Assur and the Yoke of Assur: Studies on Assyria 1971-2005" by J. Nicholas Postgate (2007) Amazon.com;

“Assyria: The Rise and Fall of the World's First Empire” by Eckart Frahm (2023) Amazon.com;

“Assyrian Empire: A History from Beginning to End” by History Hourly (2019) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Assyria” by Eckart Frahm (2017) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Assyria: A Very Short Introduction” by Karen Radner (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Might That Was Assyria” by H. W. F. Saggs (1984) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Assyria” by James Baikie (2022) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamia: an Enthralling Overview of Mesopotamian History (2022) Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamia: a Captivating Guide (2019) Amazon.com;

“A History of the Ancient Near East” by Marc Van De Mieroop (2003) Amazon.com;

Discovery of Lost Assyrian Cities

In 2013, archaeologists working in the Kurdish region of northern Iraq announced they had located the ancient city of Idu. Archaeology magazine reported: The international team unearthed the settlement while excavating a tell along the Lower Zab River. Although Idu’s existence was known from Assyrian texts, its location was previously unidentified. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2014]

Idu flourished as a provincial capital of the Assyrian Empire. During this period, and also during the interval when Idu gained its independence, the settlement featured lavish royal palaces. This prosperity is attested to by ornate bricks, cylinder seals, and artworks that depict mythological scenes. Researchers ascertained the city’s identity through a series of cuneiform inscriptions. “The discovery of Idu fills a gap in what scholars had previously thought was a dark age in the history of the ancient Near East, and it helped us to redraw the political and historical map of Assyria in its early stage,” says Cinzia Pappi, an archaeologist from the University of Leipzig.

Other lost cities have been found in recent years. In 2017, 92 clay tablets were unearthed by archaeologists from Germany’s University of Tübingen during an excavation in the village of Bassetki. By studying the tablets, researchers have discovered that the site appears to be the ancient royal city of Mardaman.“This important northern Mesopotamian city is cited in ancient sources, but researchers did not know where it lay,” a University of Tübingen statement said. “It existed between 2,200 and 1,200 years B.C., was at times a kingdom or a provincial capital and was conquered and destroyed several times.” [Source: James Rogers, Fox News, May 18, 2018]

Fox News reported: The tablets, described as “small and partly crumbling,” were deciphered by University of Heidelberg philologist Dr. Betina Faist. The cuneiform script revealed that the city was indeed Mardaman. At one point, the city was also the administrative seat of a governor in a previously-unknown province of the ancient Assyrian empire. The governor, Assur-nasir, is described in the tablets, as are his tasks and activities. “All of a sudden it became clear that our excavations had found an Assyrian governor’s palace,” added Professor Peter Pfälzner of the University of Tübingen, who led the excavation. “Mardaman certainly rose to be an influential city and a regional kingdom, based on its position on the trade routes between Mesopotamia, Anatolia and Syria.”

Also in 2017, archaeologists harnessed spy satellite imagery and drones to help identify the site Qalatga Darband in northern Iraq. The site, was first spotted when archaeologists analyzed U.S. spy satellite imagery from the 1960s that was declassified in the 1990s. Experts at the British Museum used the data to map a large number of carved limestone blocks at the site, indicating substantial remains. A drone survey highlighted other potential buildings at the site.

Assyrian Aqueducts and Water Systems

The Assyrians built the first aqueducts and paved roads. Aqueducts provided water for lavish gardens that covered the size of football fields. Parts of the most famous pre-Roman aqueducts, built by King Sennacherib for Nineveh around 700 B.C. are still visible in the north of Iraq.

Although multi-tiered, arched stone structures are what most of us visualize when we think of ancient aqueducts, most aqueduct routes consist of tunnels or pipelines at a very shallow downward slope that allow water to flow naturally from an elevated source downward to a city. The arched stone structures were placed where valleys intervened along the way, disrupting the general downward flow of the water.

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: During excavations near Nineveh’s eastern wall, archaeologist discovered a previously unknown gate, along with evidence of the Neo-Assyrians’ skill as hydraulic engineers. There, they unearthed a 135-foot-long water tunnel that passed directly through a section of the 100-foot-thick defensive wall. The conduit brought water from the nearby Khosr River into the city and is just one small part of the sophisticated water system the Neo-Assyrians developed to support a city the size of Nineveh. This hydraulic network began more than 40 miles away, in the foothills of the Zagros Mountains, where archaeologists are continuing to make intriguing discoveries. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, Features July/August 2024]

Many major U.S. cities, including New York and Los Angeles, still rely on similar technologies to supply water to their residents. Gravity is still the cheapest and most renewable source of energy, ninety-five percent of the water used in New York is still delivered by gravity.

Ashur

Ashur (on the Tigris River in northern Iraq) was the first capital of Assyria. The source of the name of the main Assyrian God (Ashur) as well as the name “Assyrian,” it first appeared around 2500 B.C. and grew into trading town that prospered from trade with Turkey. For several centuries it was dominated foreign rulers.

Ashur, also known Assur, was built along the west bank of Tigris River and dominated by a ziggurat dedicated to Assur. Temples and palaces were built in a bluff above the Tigris. There were large homes behind walls and small houses crowding around the temples. After the capital of Assyria moved to Ninmrud and Nineveh, Ashur remained a sacred city. All the kings continued to be enthroned and buried there. Pilgrims visited its temples.

Leon McCarron wrote in Smithsonian magazine: The Assyrian Empire grew out of the founding of the city-state of Ashur in the third millennium B.C. Ashur, the empire’s first capital, was believed to be the physical manifestation of the deity for whom the city was named, and the city’s main temple his eternal residence. But it was also a wealthy hub for regional trade, positioned along one of the main caravan routes, and it formed an especially lucrative trading relationship with Anatolia, in what is now Turkey. Much of what we know about the city’s early flourishing comes from a remarkable collection of more than 23,000 clay Assyrian tablets discovered at the Turkish site of Karum Kanesh, 1,000 kilometers (600 miles) away. [Source: Leon McCarron, Smithsonian magazine, January-February 2022]

The Ashur archaeological site covers about one 260 hectares (one square mile). The ruins include housing districts, temple walls and occasional monumental buildings. Most dramatic was the ziggurat, which is some 85 feet tall and once stood at least twice as high. More than 4,000 years old, it was part of a temple complex dedicated to the god Ashur. In antiquity its six million mud bricks were covered with sheets of iron and lead and inlaid with crystals. Now the great mound looked as if it were melting, with dried mud settled like candle wax around the base.

The Ashur archaeological site covers about one 260 hectares (one square mile). The ruins include housing districts, temple walls and occasional monumental buildings. Most dramatic was the ziggurat, which is some 85 feet tall and once stood at least twice as high. More than 4,000 years old, it was part of a temple complex dedicated to the god Ashur. In antiquity its six million mud bricks were covered with sheets of iron and lead and inlaid with crystals. Now the great mound looked as if it were melting, with dried mud settled like candle wax around the base.

According to UNESCO: The ancient city of Ashur is located on the Tigris River in northern Mesopotamia in a specific geo-ecological zone, at the borderline between rain-fed and irrigation agriculture. The city dates back to the 3rd millennium BC. From the 14th to the 9th centuries BC it was the first capital of the Assyrian Empire, a city-state and trading platform of international importance. It also served as the religious capital of the Assyrians, associated with the god Ashur, and the place for crowning and burial of its kings. The city was destroyed by the Babylonians, but revived during the Parthian period in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. The excavated remains of the public and residential buildings of Ashur provide an outstanding record of the evolution of building practice from the Sumerian and Akkadian period through the Assyrian empire, as well as including the short revival during the Parthian period.[Source: UNESCO]

By 700 B.C. Ashur was home to 34 major temples and three massive ziggurats, including ones for the goddess Inana and the god Ashur. Two and half miles of walls surrounded the city, most of which sat well-defended on the top the bluff. Today the great ziggurats look like eroded hills. The best preserved monument is the city’s Tabira Gate which features three arches one in front of the other.

Ashur Archaeological Site

Ashur was excavated at the turn of the 20th century by German archaeologists, who uncovered monuments and tablets that related to entire span of Assyrian history. Before the second Persian Gulf war there were plans to be build a huge dam here that would have submerged much of ancient Ashur and 60 other Assyrian sites in the valley that are for most part are unexcavated and unsurveyed.. If the dam is built as planned the bluff will become a waterlogged island and not doubt clay buildings, cuneiform tablets and statues will melt into mud.

“Only a fraction of all this has ever been excavated,” Salem Abdullah, archaeological director of the ancient city of Ashur, told Smithsonian. “There were 117 Assyrian kings. When these kings died, they were buried here.” But to date only three royal graves have been identified. “Where are the rest?” He paused. “They’re here, under our feet.”

Leon McCarron wrote in Smithsonian magazine: At the turn of the 20th century, when a German expedition established the city’s boundaries by cutting a series of trenches. The archaeologists recovered thousands of cylinder seals and baked clay tablets, some carved with cuneiform inscriptions written in the second millennium B.C., which detailed religious rituals, business transactions and other subjects. But in recent decades, archaeologists have worked at the site only intermittently. “For Iraqis, it’s expensive,” Abdullah said. “The government can’t afford it.” The last major excavation concluded in 2002. Abdullah estimates that 85 to 90 percent of the site remains unexplored. [Source: Leon McCarron, Smithsonian magazine, January-February 2022]

Threats to Ashur

The archaeological site of Ashur is located on the west bank of the Tigris River, less than 1.6 kilometers (a mile) downriver from the town of Sherqat. Sherqat is encroaching on Ashur and it is hard to make sure Ashur is protected. Leon McCarron wrote in Smithsonian magazine: The challenges are numerous. For a start, it’s nearly impossible to secure the site. A mesh fence runs along to the road, but many sections have been flattened or removed altogether. And while a visitor technically requires a ticket, without staff to enforce the rule that system hasn’t worked for 30 years. Instead, residents of Sherqat treat Ashur like a local park, wandering in for picnics. “In spring you can’t see the ground,” Abdullah said, referring to the volume of trespassers and the litter they leave behind. There is looting too. Every time it rains, topsoil washes away and artifacts—pot- sherds and even cuneiform tablets and statuettes—emerge on the surface of the ground. Although Abdullah believes Sherqatis respect the site too much to steal, it wouldn’t be difficult to pick up a few things and traffic them on the black market. [Source: Leon McCarron, Smithsonian magazine, January-February 2022]

from NimrudWe walked west, to where three broad arches of the Tabira Gate glowed like bronze in the amber light of early evening. The structure is thought to date to the 14th century B.C. Though the gate is still the best-preserved monument at the site, it sustained heavy damage in 2015 when ISIS militants, having conquered the area, blew a hole in the structure. In 2020, three years after the area’s liberation, a joint project between the American University of Iraq-Sulaimani and the Aliph Foundation, a group that works to protect cultural heritage in war zones, carried out reconstruction work on the gate. By the time I visited, the contemporary mud bricks had bedded in nicely.

Still, Abdullah remains anxious about threats to the site. His greatest worry is the planned construction of a dam 25 miles south, at Makhoul. The dam was first proposed in 2002. The following year, Unesco named Ashur a World Heritage site in danger, cautioning that the reservoir could flood numerous nearby archaeological sites. The project was halted by the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, but, with fears of regional water shortages, the government in Baghdad revived the plan. In April 2021, workers laid a cornerstone, and excavators and other construction vehicles have since appeared at the site.

Khalil Khalaf Al Jbory, head of archaeology at Tikrit University, estimates that more than 200 archaeological sites near Sherqat are at risk of flooding. Assyrian sites, constructed primarily of mud, would be lost forever. He also pointed to what he called a “social disaster,” with tens of thousands of people facing displacement. “The government is not listening,” Al Jbory told me. “Not to the academics, or geologists, or anyone. It’s very dangerous, and very risky.” Abdullah had not lost hope, but he agreed that Ashur’s future was dire unless something could be done to alter the plans. “When I say this is my grandmother, I mean that I also see her wrinkles,” he told me. “She needs help now.”

Nimrud

Nimrud (35 kilometers, 23 miles southeast of Mosul, Iraq) was the second capital of the Assyrian empire. King Ashurnasirpal II (883 to 859 B.C.) moved the capital of Assyria there in 879 B.C. He built a vast walled city , with a citadel, temples, royal places and residences for thousands of people forcibly settled there. Among the extraordinary treasures unearthed in Nimrud are 169 pounds of gold treasures, mysterious ivory plaques and delightful sculptures and bas-reliefs.

Nimrud is just south of Mosul, Iraq’s largest city in the north and second largest city overall. The second capital of the ancient kingdom of Assyria, it was built about 1250 B.C. and destroyed in 612 B.C. At its height, it was the center of one of the most powerful states at the time, reaching through modern-day Egypt, Turkey and Iran. Nimrud was known in the Bible as Calah,

Nimrud was known as Kalhu in Assyrian times. It is mentioned in the Bible. Genesis 10:8-12 discusses the “great city” of Calah — same as Kalhu — and how the “mighty hunter” Nimrod established the dynasty of the Assyrians. According to the Washington Post: “The discoveries at Nimrud have been described as among the most significant archaeological finds of ancient Mesopotamia. The area was known by Western experts for centuries, but extensive excavations began after World War II. Nimrud also showcases the region’s rich history as an important crossroads among pre-Islamic civilizations, including areas mentioned in the Bible and other texts. British archaeologist Max Mallowan and his wife, crime writer Agatha Christie, worked at Nimrud in the 1950s. [Source: Daniela Deane and Brian Murphy, Washington Post, March 6 2015]

Nimrud is about 385 kilometers (240 miles) northwest of Baghdad. Mosul and Nimrud were captured an occupied by Islamic State in 2014 and held until November 2016. See Nimrud ruined by Islamic State

Nimrud Buildings and Bas-Reliefs

Nimrud is one of the best preserved of Iraq’s ancient cities. Enriched by plunder and tribute, it was the home of huge buildings and monumental sculptures .The ruins of several buildings and sections of the 8-kilometer-long wall remain today. The most impressive structure is the palace of King Ashurnasirpal II built around 700 B.C. At two of the entrances are sculptures of human-headed lions with bird wings. Inside are some lovely bas-reliefs. At the entrance to the throne room is a human-headed winged bull called “lamassu” and four-winged deity called a “ apkallu” .

Nimrud bas-relief

According to UNESCO: Nimrud was founded during the 13th century B.C. It was considered as the second capital of the Assryian Empire, known as(kalhu or kalah ), flourished during the reign of the King Ashurnasirpal. It's circumference is nealy 8 km., surrounded by a huge defensive mudbrick wall covering an area square 13 Km of 3,8 . At the south-western and south- eastern corners there constructed a height named (Accropolis) built on a terrace of mudbrick of over 40 m. high above the river level Recently, in the 1980's excavations revealed three royal tombs with marvelous treasures . Also it was discovered a (Huge Stoney wall) called a Misenat still extant of 26 foot high above the old bottom of the river. It is frontiered from the south side by An-Nugoob channel dated back to the 8th century B.C. [Source: UNESCO]

Unfortunately, many of the bas-reliefs and sculptures that remained have been damaged or removed by looters The wonderful collection of ivories displayed in the National Museum in Baghdad were found in a well of the Royal Palace. In the early 2000s, a gateway with mythical figures carved from Mosul marble was excavated at the city’s Temple of Ishtar.

According to UNESCO: Many of Nimrud’s most famous surviving monuments were removed years ago by archaeologists, including colossal Winged Bulls, now housed in London’s British Museum, which also possesses probably the finest collection of Nimrud friezes, thanks to the archaeologist Austen Henry Layard, who rediscovered the palace of Ashurnasirpal II in 1845. They show life at Ashurnasirpal II’s court, while inscriptions reveal his brutality. Hundreds of precious stones and pieces of gold were moved to Baghdad. However, several of the giant winged bulls were left in situ in Nimrud, and Nineveh too, while the Northwest Palace was specially reconstructed to house the friezes. It was the only place in the world where people could see this hallmark of the Assyrian civilisation as it would have originally looked.

Ostrich Eggshells, Carved Hippo Ivory Found at Palace in Nimrud

In December 2022, archaeologists said they discovered precious objects made of ostrich eggshells, elaborately painted walls and furniture inlaid with carved hippopotamus and elephant ivory at the palace of King Adad-Nirari III in Nimrud, an old capital of the Assyrian empire and city in modern-day Iraq. The findings were made Michael Danti, who works at the University of Pennsylvania’s Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, and his team from the Iraq Heritage Stabilization Program and Penn Museum. [Source: Aspen Pflughoeft, Miami Herald, December 16, 2022]

According to the Miami Herald: King Adad-Nirari III took the throne as a young boy, ruling the Assyrian empire around 800 B.C. during a time of fragmentation, Danti said. However, his mother, Queen Shammuramat, “essentially ran the empire. … She went on military campaigns, and, unlike other royal ladies, had royal inscriptions in public places,” Danti said. The queen, also known as Sammuramat or Shamiram, was “a very powerful female ruler.” King Adad-Nirari III’s palace — or, as some scholars argue, his mother’s palace — is one of the “most poorly known” palaces, Danti said. A British archaeologist excavated a small portion of the site in the 19th century, but many questions remain unanswered.

Excavating the 2,800-year-old palace has revealed “amazing” and “fabulous” finds, Danti said. Archaeologists have unearthed fragments of fallen wall paintings with “elaborate” designs, objects made of ostrich eggshells, carved elephant and hippo ivory, bronze objects, inscribed metal slabs and brick pavements, an “unprecedented” marble column base with a style like “no one has ever seen,” and a large slab of marble with a bowl-like indentation in the center and tram-like rails that servants would have used to roll around a metal wagon with a fire inside, he said.

For Danti, however, one find stands out: a door sill with a cuneiform inscription. Archaeologists uncovered and documented the threshold in the 19th century, but the find was reburied amid years of warfare, conflict and fighting in Iraq. “To see it in person … to see the size of it, the beauty of the cuneiform writing system on it, just the monumentality of it, it blew us all away,” Danti said. “We were elated and we were just dumbstruck. … I don’t know how to describe it, it was the size of the thing and the craftsmanship.”

A few minutes walk away from the palace, Danti’s team is also excavating the acropolis, or “high mound at the center” of Nimrud. The joint team of Iraqi and American archaeologists are clearing away debris left from ISIS explosions, he said. Before the explosion, Iraqi archaeologists had “painstakingly reconstructed” a portion of the Ishtar Temple, a massive temple built around 900 B.C. and dedicated to the Mesopotamian goddess of love and warfare, Danti said.

Archaeologists hope to reconstruct the temple once again — a project that began by de-mining the site and clearing any unexploded ordnance, Danti explained. Once the rubble is gone, archaeologists can assess what’s left of the site and what needs to be done next.

Nineveh

Nineveh (on the outskirts of Mosul, Iraq) was the third capital of the Assyrian Empire. It began as a trade center of a province of Babylonia. By 1400 B.C. it had developed into a strong independent state. The capital of Assyria moved from Nimrud to Nineveh by King Ashurnasirpal II (883 to 859 B.C.) in 863 B.C. Describing as the “exceeding great city,” it was at its peak from 883 to 612 B.C., when it was home to 100,000 people — twice the size of Babylon when it at its peak. In 612 B.C. Nineveh was destroyed by an alliance of Medes (former vassals of the Assyrians), Cimmerians (sometimes confused with Scythians) and Chaldeans, bringing the Assyrian Empire to an end.

Nineveh was mentioned in The Bible several times. Jonah traveled there by whale. The Old Testament’s Book of Nahum described the months-long siege of Nineveh by Medes: “Woe to the city of blood, full of lies, full of plunder, never without victims. The crack of the whips, and rumble of wheel, galloping horses, and jilting chariots. Charging cavalry, flashing swords, and glittering spears! Many casualties, piles of dead bodies without number, people stumbling over the corpses — all because the wanton lust of a harlot, alluring, the mistress sorceries, who enslaved nations by her prostitution and peoples by her witchcraft,.”

Nineveh was mentioned in The Bible several times. Jonah traveled there by whale. The Old Testament’s Book of Nahum described the months-long siege of Nineveh by Medes: “Woe to the city of blood, full of lies, full of plunder, never without victims. The crack of the whips, and rumble of wheel, galloping horses, and jilting chariots. Charging cavalry, flashing swords, and glittering spears! Many casualties, piles of dead bodies without number, people stumbling over the corpses — all because the wanton lust of a harlot, alluring, the mistress sorceries, who enslaved nations by her prostitution and peoples by her witchcraft,.”

The “palace without rival? of the Assyrian King Sennacherib boasted inner walls lined with two miles of stone sculptures depicting the king’s campaigns. Within the palace archeologists discovered thousands of cuneiform tablets, some of the earliest known collection of writing. Many sculptures and stone slabs with bas reliefs have been hacked away by looters.

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: Although excavators have found that people have lived in the area of Nineveh for at least 9,000 years, Sennacherib utterly transformed the settlement. Monumental architecture, inscriptions, and tablets all provide evidence of what the city once looked like. It had one of the ancient world’s most imposing defensive walls, which measured more than 100 feet tall and 100 feet wide in places and encircled an area of about three square miles, more than twice the size of New York City’s Central Park. These walls had at least 18 gates, one flanked with giant lamassu statues similar to the one recently rediscovered in Khorsabad. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, Features July/August 2024]

Nineveh Layout and Buildings

Ancient Nineveh covered 1,730 acres and boasted gardens, temples and a royal library.It was surrounded by a 12-kilometer-square wall with 15 gates, each named after an Assyrian god. Much of this wall was rebuilt in the early Saddam Hussein years. Several of the gates have been reconstructed.

According to UNESCO: Nineveh was one of the most important cultural centers inthe ancient world enjoying a prominent role in the field of developing human civilization, in that it was the greatest metropolis where various branchesofartsandlearning originated. It was adopted by the Assyrians as their political seat and comes next to their first religious capital city Ashur.Excavation on the principle mound in the city, Kuyunijk, has shown that it was occupied from c.6000 BC.-AD 600, Nineveh was oRen a royal residence and was finally established as the capital of theAssyrians about 700 BC. by Senacherib, whose successors lived there until its destruction in 612 BC. The city wall of Nineveh has a circumference of over 12 km. And six gates have been excavated. On the mound of Kuyunjik the throne-room suite of Senacherrib's palace has re-excavated with some of its relief slabs depicting the Kings conquest still in position, the mound of Nebi Yunusj the site of the imperial arsenal 1.6 km; South of Kuyunjik, has been covered with houses grouped around a mosque, containing the reputed tomb of Jonah. [Source: UNESCO]

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: There were two large tells, or acropolises. The larger of these, known as Tell Kuyunjik, still rises 130 feet above the surrounding plain and once featured administrative buildings, luxurious palaces, and imposing temples. The city had grand houses with courtyards, broad processional streets, archives, and carved statues and reliefs. It also contained lush gardens, parks, and even menageries of exotic plants and animals captured in the far-flung reaches of the Assyrians’ territory. “The idea is that these gardens serve as a microcosm of all of the wonders of the empire, so that the people living back in the imperial capital can see just how great the empire is,” says Danti. “It would have been incredibly impressive.” [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, Features July/August 2024]

Perhaps the most surprising revelation has been how densely occupied Nineveh truly was. Scholars had assumed that swaths of the city within the walls were dedicated to open spaces, gardens, and pasturelands, especially in the northeast corner, where few archaeological features were visible on the surface. However, geophysical surveys have indicated quite the opposite. “They revealed a very packed situation with houses and narrow alleys—there is not a single empty square meter,” Marchetti says. “Prior to our work, Nineveh was thought to have had large empty areas, but there is nothing of the kind.”

North Palace of Nineveh

Nineveh Mashki Gate

The North Palace of Nineveh was erected between 646 and 644 B.C. for Ashurbanipal. According to National Geographic: The momentous building project was made possible largely thanks to the loot and material resources captured in Assyria’s decisive victories over Elam and Babylon. The North Palace stood raised on a large terrace around 20 feet high, next to the temple of Ishtar, a goddess whom Ashurbanipal asked to protect his new residence. Hundreds of laborers and conscripts, including many prisoners of war, were put to work on the palace under the orders of the king. [Source: National Geographic, National Geographic,, August 25, 2022]

Like the vast majority of Assyrian buildings, the North Palace was built of mud brick, so little remains of the original structure. Fortunately, though, the buildings were decorated with stone bas-reliefs, many of which have survived. Their artistry and the depth of their detail yield valuable insights into the life and personality of the Assyrian king.

Ashurbanipal sought magical protection for his lavish palace to keep evil spirits at bay; the practice was nothing new. His grandfather Sennacherib and great grandfather Sargon II had entrusted the work of protection to the lamassu, colossal bulls and winged lions with human heads. But Ashurbanipal dispensed with these impressive creatures, turning instead to representations of the Sebetti, powerful protective spirits from Mesopotamian mythology, to guard his throne room.

Art in the North Palace of Nineveh

According to National Geographic: Many of the reliefs in the throne room of the North Palace of Nineveh depicted battle scenes, commemorating Ashurbanipal’s great military victories, including the campaigns against Babylon, Elam, Egypt, and the Arab tribes. Although Ashurbanipal rarely accompanied his soldiers onto the battlefield, he created a powerful iconography through these elaborate reliefs that would preserve a legacy as a great military leader. [Source: National Geographic, National Geographic,, August 25, 2022]

In the palace’s private rooms, which few had access to, the king chose a slightly different emphasis for the reliefs. In these spaces the military-themed reliefs are mixed with scenes that depict the king celebrating his triumphs. One panel shows Ashurbanipal performing a ritual libation using the severed head of the Elamite king Teumman, whom he defeated at the Battle of Til-Tuba (the defeated king’s head was also paraded through the streets of Nineveh). These images of military victories and triumphal celebrations seem contrived to send visitors a clear message of the price paid by those who dared to resist Assyrian power.

Perhaps the most famous pieces of art from the North Palace are the reliefs of a lion hunt, the sport of kings in ancient Assyria. Rendered in a striking, lifelike manner, Ashurbanipal and his retinue kill multiple lions, whose painful deaths are shown in gruesome detail. This stone relief depicts with astonishing realism the death throes of a male lion that has been mortally wounded by Ashurbanipal during a ritual lion hunt. It belongs to a series of stone panels showing hunting scenes that decorated the hallways in Ashurbanipal’s North Palace in Nineveh. Such hunts were sacred to Assyrian kings as they symbolized the king’s ability to protect his people. As early as the ninth century B.C., a royal inscription records Ashurnasirpal II boasting of his hunting prowess: “The gods Ninurta and [Nergal, who love my priesthood, gave to me the wild beasts and commanded me to hunt]. 300 lions ... six strong [wild] virile [bulls] with horns ... and the winged birds of the sky.”

In the Sebetti Panel from the north palace in Nineveh, circa 645-640 B.C., Three bearded figures on a relief once stood watch over an entrance to the throne room of Ashurbanipal’s North Palace. Painted in colorful hues, they were more than just mere decoration. Researchers have identified them as representations of the Sebetti, a group of minor warrior deities from the Mesopotamian pantheon. Each wields an ax in the right hand and a dagger in the left (analysis of the relief shows that they originally were armed with bows rather than these handheld weapons). These three protective spirits were probably complemented by another relief (which has not been recovered) featuring four more figures, as the Sebetti were depicted in groups of seven and associated with the Pleiades, a closely grouped cluster of seven stars in the constellation Taurus. Another common depiction of the Sebetti was an emblem of seven dots. Worship of these spirits dated back centuries before Ashurbanipal’s rule, as evidenced in inscriptions and temples built by earlier kings Sennacherib (reigned 705–681 B.C.) and Ashurnasirpal II (reigned 883-859 B.C.).

Irrigation and Waterworks in the Hinterlands of Nineveh

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: While other projects have concentrated on the core of the city and its immediate surroundings, archaeologists from the University of Udine, in collaboration with Kurdish and Iraqi authorities, have made the hinterland of the great Neo-Assyrian capital their focus. Scholars working with a wide-ranging multidisciplinary venture called the Land of Nineveh Archaeological Project (LoNAP) are investigating 1,200 square miles of terrain in the Duhok region of Iraqi Kurdistan, the first extensive fieldwork that has taken place in the area in nearly a century. They are learning that just as the Assyrian capitals grew exponentially in the eighth and seventh centuries B.C., so did the population of the surrounding countryside. And, for the first time, researchers are arriving at a better understanding of the extensive water supply system engineered by Sennacherib to support both urban and rural settlements. Over the course of just 15 years, between 703 and 688 B.C., Sennacherib constructed more than 200 miles of canals, weirs, dams, tunnels, and reservoirs. Channels were dug through bedrock, rivers diverted, natural springs enlarged, and aqueducts erected. “These are the first known stone aqueducts in history and predate the Roman ones by roughly four centuries,” says University of Udine archaeologist Daniele Morandi Bonacossi, who is codirector of LoNAP.[Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, Features July/August 2024]

While digging near the village of Faida, Morandi Bonacossi’s team brought to light a rare set of reliefs—the first of their kind to be fully excavated in nearly two centuries—carved into the side of a rock-cut canal. These reliefs were first identified in the 1970s and later investigated by Morandi Bonacossi beginning in 2012. Yet, as happened in so much of the land in and around Nineveh, recent events brought the work to a halt. The team has now completed the excavation of the canal. (See “The King’s Canal,” May/June 2020.) “The security situation in the area led to the postponement of the beginning of our archaeological project at the site,” says Morandi Bonacossi. “But in 2019, together with the Duhok Directorate of Antiquities and Heritage, we launched a rescue project aimed at salvaging the canal and its rock reliefs. The true extent of the Assyrians’ sculptural program only became clear forty years after its first partial discovery.”

The channel’s 13 carved panels each measures more than six feet high and 15 feet wide, and are spread out over at least a mile. Each panel depicts a cultic scene involving a procession of statues of the seven principal Assyrian deities—Ashur, Mullissu, Sin, Nabu, Shamash, Adad, and Ishtar—standing atop striding animals. At either end of the parade of deities, there are images of a king, probably Sennacherib, who had the artwork commissioned to commemorate his achievement in constructing the canal. Morandi Bonacossi believes that there are almost certainly other rock-cut reliefs along the six-mile canal but is content to leave them buried, where they are safe from harm. “It’s always a good idea not to exhaust an archaeological site,” he says, “so that other generations who will operate with new methods and technological instruments can check and improve our understanding.”

Archaeological Work at Nineveh

After its destruction in 612 B.C. Nineveh slipped into relative obscurity. Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: The city’s exact location would remain largely unknown until the nineteenth century when the site gained worldwide attention after European archaeologists began to explore its rumored position. They soon unearthed sprawling buildings, massive statues, and more than 30,000 inscribed cuneiform tablets collected by Sennacherib’s grandson Ashurbanipal (reigned 668–631 B.C.), who established one of the ancient world’s greatest libraries (see “Royal Bibliophile.”). These early excavations showed that the Neo-Assyrians were far more than their reputation for warmongering and greed had led people to believe. Nineveh had been a place of wonder. When archaeological exploration came to a stop in the late twentieth century, reports of damage began to spread, and archaeologists feared that Nineveh was in danger of being lost once again. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, Features July/August 2024]

John Malcolm Russell wrote in Archaeology magazine: “In 1847 the young British adventurer Austen Henry Layard explored the ruins of Nineveh and rediscovered the lost palace of Sennacherib across the Tigris River from modern Mosul in northern Iraq. Inscribed in cuneiform on the colossal sculptures in the doorway of its throne room was Sennacherib's own account of his siege of Jerusalem. It differed in detail from the biblical one but confirmed that Sennacherib did not capture the city. This find generated an excitement that is difficult to imagine today, because amid the increasing religious doubt and scriptural revisionism of the mid-nineteenth century, it gave Christian fundamentalists an independent eyewitness corroboration of a biblical event, written in the doorway of the very room where Sennacherib may have issued his order to attack. The palace's interior walls were paneled with huge stone slabs, carved in relief with images of Sennacherib's victories. Here one could see the king and army, foreign landscapes, and conquered enemy cities, including a remarkably accurate depiction of the Judean city of Lachish, whose destruction by the Assyrians was recorded in II Kings 18:13-14. [Source: John Malcolm Russell Archaeology, December 30, 1996]

“Considering that the palace had been destroyed by an intense conflagration during the sack of Nineveh in 612 B.C., the massive walls and many of the relief sculptures of Sennacherib's throne-room suite were surprisingly well preserved. In the 1960s, because of the palace's historical importance and unique preservation, the Iraq Department of Antiquities consolidated the walls and sculptures and roofed the site over as the Sennacherib Palace Site Museum at Nineveh, where visitors could tour one of only two preserved Assyrian palaces in the world. (The other is the palace of Assurnasirpal II at Nimrud, also restored as a site museum.) The four restored rooms of the throne-room suite, designated H, I, IV, and V by Layard, contained some 100 sculptured slabs in various states of preservation. In two of these rooms, IV and V parts of nearly every slab survived, making these the most completely preserved decorative cycles in the palace. Most of these reliefs have never been published. Some show unusual subjects and provide valuable information on visual narrative composition in Assyrian palace decoration. These reliefs needed to be documented in case the originals were lost or damaged and to guide future conservation efforts.”

More recently, Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: An inscribed terracotta cylinder was discovered in a private residence in Nineveh. The text describes some of Sennacherib’s military campaigns as well as the construction of his royal palace and other buildings. This has led to the discovery of a wide array of residential properties, ranging from humble abodes to sumptuous villas with expansive courtyards. The researchers have found evidence of administrative and economic activities in the form of cylinder seals, amulets, and tokens, as well as financial transactions recorded in cuneiform on clay tablets. One spectacular discovery was a house belonging to a baru, or “diviner,” who specialized in reading omens and interpreting the will of the gods. Archaeologists found piles of inscribed texts buried within the property related to the baru’s practice. There are incantations and literary texts, including a copy of an epic poem known as the Lugal-e, which recounts the exploits of the Mesopotamian warrior god Ninurta. The excavations have also uncovered the most complete description ever found of a mysterious ceremony known as the Mis-Pi. During this ritual, incantations were performed around a newly created statue of an Assyrian deity, allowing the spirit of the god to inhabit the statue and bring it to life. “It’s an incredibly important ritual, and although it is well-known, there were huge lacunae,” Marchetti says. “These texts now allow our philological team to fill in these gaps. It was an unexpected and beautiful discovery.” [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, Features July/August 2024]

The baru’s cuneiform tablets were not the only cache the team uncovered. In a small palace near the Adad Gate, they excavated an area believed to be a scriptorium. One room contained a large block of clay and a writing stylus, while an adjacent room had benches where researchers believe that texts were created and copied. Further investigation nearby revealed more than 200 inscribed clay tablets that included magical incantations and descriptions of omens, as well as literary and medical texts. “What’s especially interesting is that most of them aren’t duplicates, but are texts that were unknown until now,” Marchetti says. “It’s a unique find that is the most important epigraphic discovery at Nineveh after Ashurbanipal’s library.”

Arbela (Erbil)

Arbela (Erbil) is a 6000-year-old settlement-city in modern-day Iraqi Kurdistan that grew into a major city under the Assyrians: Andrew Lawler wrote in Archaeology magazine: “The Assyrian Empire reached its height in the seventh century B.C., when the kings Sennacherib, Esarhaddon, and Ashurbanipal ruled the region, including Arbela [Erbil]. Contemporary Assyrian texts describe the Egasankalamma as a richly decorated and elaborate complex where royals regularly came to seek the goddess’ guidance. Esarhaddon claimed that he made the temple “shine like the day,” likely a reference to a coating of a silver-and-gold alloy called electrum that gleamed in the Mesopotamian sun. A fragment of a relief from the Assyrian city of Nineveh shows the structure rising above the citadel walls. Some Assyrian royals may have lived there in their youth, perhaps to keep them safe from court intrigues at the capitals of Nineveh, Nimrud, and Assur in the empire’s heartland. On one tablet Ashurbanipal says, “I knew no father or mother. I grew up in the lap of the goddess”—Ishtar of Arbela. [Source: Andrew Lawler, Archaeology, September-October 2014 ]

“An inscribed clay cylinder found at Nimrud details how the Assyrian King Esarhaddon made Arbela’s temple to Ishtar “shine like the sun.” Under the Assyrians, Arbela was a cosmopolitan gathering place for foreign ambassadors coming from the east. “Tribute enters it from all the world!” says Ashurbanipal in one text. A governor oversaw the city’s administration from a sumptuous citadel palace where taxpayers brought copper and cattle, pomegranates, pistachios, grain, and grapes. Arbela’s own inhabitants were a diverse mix that likely included those forcibly resettled by the Assyrian state, as well as immigrants, merchants, and others seeking opportunity in a city that rivaled the Assyrian capitals in stature. “Arbela at this time was a multiethnic state,” says Dishad Marf, a scholar at the Netherlands’ Leiden University. Names of its citizens found in Assyrian texts are Babylonian, Assyrian, Hurrian, Aramain, Shubrian, Scythian, and Palestinian.

“Assyrian royalty also lavished gifts and praise on Arbela and its patron deity. “Heaven without equal, Arbela!” proclaims one court poem found in Nineveh’s state archives. The poem also describes Arbela as a place where merry-making, festivals, and jubilation echoed in its streets, and Ishtar’s shrine as a “lofty hostel, broad temple, a sanctuary of delights” resounding with the music of drums, lyres, and harps. “Those who leave Arbela and those who enter it are happy,” the hymn concludes. Not all, however. The Nineveh relief depicting Arbela includes a king, likely Ashurbanipal, pouring a libation over the severed head of a rebel from Arbela. According to ancient records, the king had the surviving agitators chained to the city gates, flayed, and their tongues ripped out.

Nineveh Adad gate and north exterior

“Arbela’s formidable walls and arched gate are depicted in a seventh-century B.C. stone relief found at Nineveh.After so many centuries of regional domination, the Assyrians’ fall was sudden and swift—and Arbela proved to be the sole surviving major settlement. A coalition of Babylonians and Medes, a nomadic people who lived on the Iranian plateau, destroyed the Assyrian capitals in 612 B.C. and scattered their once-feared armies. Arbela was spared, perhaps because its population was in large part non-Assyrian and sympathetic to the new conquerors. The Medes, who may be the ancestors of today’s Kurds, likely took control of the city, which was still intact a century later when the Persian king Darius I, third king of the Achaemenid Empire, impaled a rebel on Arbela’s ramparts—a scene recorded in an inscription carved on a western Iranian cliff around 500 B.C.

“By the fourth century B.C., the Achaemenid Empire stretched from Egypt to India. In the fall of 331 B.C., on the plain of Gaugamela to the west of Arbela, the Macedonian king Alexander the Great fought the Achaemenid ruler Darius III, routing the Persian army as its king fled. Classical sources say that Alexander pursued Darius across the Greater Zab River to Arbela’s citadel, where historians believe the Persian king had his campaign headquarters. Darius escaped east into the Zagros Mountains and was eventually killed by his own soldiers, after which Alexander assumed the leadership of the Persian Empire, possibly in a ceremony held in Arbela’s temple of Ishtar, whom he may have equated with the Greek warrior-goddess Athena.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024