Home | Category: Arabs and Arabic

ARABIC: SUPER DIFFICULT TO LEARN

Sam Dillon wrote in New York Times: “For Americans, Arabic is a difficult language. It has some unfamiliar throaty sounds, a vast and ancient vocabulary, script that reads from right to left and dialects so distinct that native speakers from Morocco, Yemen and Iraq often cannot understand one another...The Foreign Service Institute at the State Department puts Arabic in its ''super-hard'' category, along with Chinese, Japanese and Korean, said James E. Bernhardt, chairman of the institute's department of Arabic and Asian languages. The institute estimates that bright students need at least 88 weeks of full-time training to reach entry-level professional proficiency, he said. By comparison, to achieve the same proficiency in Hebrew, which the institute rates as ''hard,'' requires 44 weeks, Mr. Bernhardt said. [Source: Sam Dillon, New York Times, November 16, 2003]

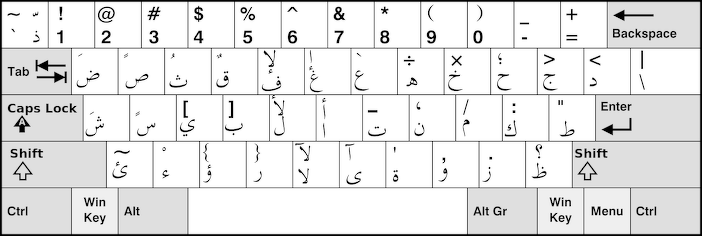

Jennifer Bremer wrote in the Washington Post: “What makes Arabic such a hard language for an English speaker to learn? The first challenge is the alphabet, in which a dot can transform an "n" into a "t" or an "h" into a "g." Second, because Arabic shares few words with English, a student starts from scratch to build up a working vocabulary. Arabic grammar is downright complicated as well, and very different from English in basic issues like word order. [Source:Jennifer Bremer, Washington Post, October 16, 2005 ***]

Robert Lane Greene wrote in Slate.com: “Learning Arabic is complicated. The first challenge, the script, is a tough one. But it is by no means the biggest. Arabic has an alphabet, so it's easier than, say, Chinese, which has a set of thousands of characters. There are just 28 letters, and it does not take long to get used to writing and reading right-to-left. (Though it still feels odd to open my book from what seems like the back.) Most of the letters have four different forms, depending on whether they stand alone or come at the beginning, middle, or end of a word. Even then, so far so good. But in Arabic, as in Hebrew, people don't include most vowels when writing. Maktab, or "office," is just written mktb. Vowels are included as little marks above and below in beginning textbooks, but you soon have to get used to doing without them. Whn y knw th lngg wll ths s nt tht hrd. But when you're struggling with comprehension to begin with, it's pretty formidable. [Source: Robert Lane Greene, Slate.com, June 9 2005 \~]

“Then there are the sounds those letters represent. I do not recommend chewing gum in Arabic class, because a host of noises articulated in the back of the throat makes it likely that the gum will end up in your lungs. Arabic has one "h" akin to ours, and another that has been described as the sound you would make trying to blow out a candle with air from your throat. That's not to be confused with another sound, the fricative kh familiar to German-speakers as the sound in "Bach." There's also 'ayn, a "voiced pharyngeal fricative," which is like the first sound in the hip-hop "a'ight." Unwritten in Roman-alphabet transliterations, it's actually a consonant that begins many common words and names, including "Arab," "Iraq," and "Arafat."

“The sounds are tough, but the words are tougher. An English-speaking student learning a European language will run across many familiar-looking words, but English-speaking Arabic students are not so lucky. Merav, an Israeli classmate, should have a leg up on us: Arabic and Hebrew both use a nifty, three-letter root system for word building. The three-letter root represents a general area of meaning, and different prefixes, vowel additions, and suffixes can make it into a person engaged in that activity, the place where it goes on, the general concept, and so on. Most famous is slm, which generally means "peace." Salaam is the noun for "peace," Islam is "surrender," and a Muslim is "one who surrenders." (In Hebrew, this can be seen in shalom.) Ktb functions similarly for writing: Kitaab is "book," kaatib is "writer," maktaba is "library." The State Department reckons that it takes 80 to 88 weeks (roughly a year in the classroom full-time and a year in-country) to get to a level 3 on a 5-point scale in Modern Standard Arabic, the language I am learning.

Arabs: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Who Is an Arab? africa.upenn.edu ; Encyclopædia Britannica article britannica.com ; Arab Cultural Awareness fas.org/irp/agency/army ; Arab Cultural Center arabculturalcenter.org ; 'Face' Among the Arabs, CIA cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence ; Arab American Institute aaiusa.org/arts-and-culture ; Introduction to the Arabic Language al-bab.com/arabic-language ; Wikipedia article on the Arabic language Wikipedia

Arabic’s Special Challenge: MSA Verus Colloquial Arabic

Arabic and Hebrew

Jennifer Bremer wrote in the Washington Post: “Unlike most languages, Arabic has two, very different, versions. Arabs use one language for writing and other formal purposes and another for day-to-day conversation. The formal language, usually called Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), is a streamlined version of the classical language, elegant and expressive, but hard to learn. The commonly spoken language (colloquial, or aamiya) uses different grammar, even different vocabulary from MSA. "How are you?" in MSA, for example, is " Kayf halak?" In Egyptian colloquial, it's " Izzayak?" [Source:Jennifer Bremer, Washington Post, October 16, 2005 ***]

“Colloquial Arabic is much easier to learn than MSA. It lacks MSA's grammatical niceties. In MSA, for example, nouns take case endings, as in Latin or German; colloquial doesn't bother with such folderol. Colloquial is often taught using familiar English letters instead of Arabic script -- why bother with all those troublesome dots when colloquial is rarely written down, anyway? ***

“Despite colloquial's user-friendliness, most language programs in the United States (including those at the State Department) teach Modern Standard. This choice does not reflect linguistic elitism, at least not entirely. MSA has both advantages and disadvantages. On the plus side, it remains constant from Morocco to Iraq. All educated Arabs can speak and understand MSA, although native speakers would usually rely on colloquial outside of a formal setting such as a lecture hall or courtroom. ***

“MSA is widely used in diplomatic settings, even among Arabs. An Egyptian and a Moroccan or an Iraqi speaking together might well choose MSA because their respective colloquial languages are very different. Where an Egyptian would ask how you are with "Izzayak?" an Iraqi would say "Shlonek?" MSA's close association with classical Arabic keeps it from straying too far from the elegant 7th-century language of the Holy Qur’an. Colloquial dialects, conversely, have mixed and mingled freely with local and Western languages. To an Egyptian, potato is butatis , but to an Iraqi, it's puteeta. ***

“The written/spoken difference helps to explain the relatively high illiteracy rates in the Arab world, especially in rural areas with less exposure to formal speech. In rural Algeria, illiteracy tops 50 percent for men and 85 percent for women. In effect, students must learn to read in a foreign language, as different from their own as Chaucer is from today's English.” ***

Robert Lane Greene wrote in Slate.com: “MSA has about the same role in the Arab world that Latin had in medieval Europe: It's the language of writing, religion, and formal speeches, but it is no one's native spoken language any more. Arabic has long since become a series of "dialects," which are actually more like separate languages, as many varieties are mutually incomprehensible. Arabic spoken in Morocco is as different from Arabic spoken in Egypt and from Modern Standard as French is from Spanish and Latin. When Arabs from different regions talk to each other, they improvise a mix of Egyptian Arabic (which is understood widely because of Egypt's movie industry), Modern Standard, and a bit of their own dialects. [Source: Robert Lane Greene, Slate.com, June 9 2005 \~]

“So, if I go to Egypt or Lebanon in a year, having managed to get some near grip on my classroom language, I will be walking down the street asking people for a bite to eat in something that will sound almost as conversationally inappropriate to them as Shakespearean English would to us. Most literate Arabs know the Modern Standard from schooling, newspapers, television, sermons, and the like, though, so hopefully they will not laugh too hard as they help me out and respond in something I can almost understand. And that is if I work my tail off for the next year. Insha'allah.” \~\

Arabic is the Fastest Growing Language in U.S.

comparison of Hebrew and Arabic

According to a 2016 study by the Pew Research Center, Arabic is the fastest growing language in the U.S., with the number of Arabic speakers growing by 29 percent between 2010 and 2014. Over the longer period from 2000 to 2014, the number of Arabic speakers in the U.S. nearly doubled, rising from 615,000 in 2000 to 1.1 million by 2014, according to the study, which analyzed data from the U.S. Census Bureau. [Source:Jeannette Richard, CNS News, June 17, 2016 /=/]

Jeannette Richard wrote in CNS News: “The number of people ages 5 and older who speak Arabic at home has grown by 29% between 2010 and 2014 to 1.1 million, making it the seventh most commonly spoken non-English language in the U.S.,” the study said. As a result, census questionnaires will be available in Arabic for the first time in 2020, Pew reports. /=/

“The study noted that the number of people who speak Spanish at home has only grown 6 percent during that same time period. Among those who speak Arabic at home, 38% were not proficient in English – that is, they report speaking English less than ‘very well',” the study added, noting that this percentage is similar to the 42 percent of people who speak Spanish at home who are not proficient in English.

Robert Lane Greene wrote in Slate.com: Arabic is “a language long neglected by Americans in the years before Sept. 11. Since then, the CIA and the military have tried to recruit Arab-American "heritage speakers." The federal government has spent tons of money, both teaching Arabic to spies and soldiers at its specialized schools and encouraging university students to study it. College enrollment in Arabic classes doubled between 1998 and 2002, with much of the increase coming in a patriotic spike after the World Trade Center attacks. [Source: Robert Lane Greene, Slate.com, June 9 2005 \~]

Lack of U.S. Diplomats That Can Speak Arabic

In 2005, Jennifer Bremer wrote in the Washington Post: “At a time when the U.S. government has an urgent need both to understand what's being said in the Arab world and to express our own views clearly, surely every U.S. embassy in the Mideast is staffed with at least several American diplomats who speak Arabic, right? Well, no. Four years after 9/11, we're still a very long way from achieving this fundamental goal, as the State Department's internal performance reviews and interviews with human resource and language training staff make clear. Policy is not the problem: State Department planning documents call for increased Arabic language capabilities in the Foreign Service. The problem is that the way we're going about meeting this goal guarantees failure. [Source: Jennifer Bremer, Washington Post, October 16, 2005]

“To understand why requires a safari into the bureaucratic undergrowth, so grab your machete. The Foreign Service classifies language ability into five levels, with "1" being the lowest (able to handle only the very simplest social situations) and "5" the highest (a level rarely assigned to anyone but a native speaker).

“From a public diplomacy standpoint, the key distinction is between a "3" and a "4." We have a fairly good supply of 3's in Arabic, almost 200 as of August 2004 (the latest State Department data available). A level 3 can handle one-on-one situations, or something like a ministry meeting in a subject area they know well. But a level 3 speaker would flounder in a complex situation. If you put a 3 in a public meeting where many excited people are speaking on top of one another, for example, or in a coffee shop conversation with college students arguing about religion and the state, he or she would be lost. Double the difficulty if the diplomat has been trained only in Modern Standard Arabic, a formal dialect very different from the colloquial dialects that people actually speak (see sidebar). But these are precisely the kinds of situations that our Middle East diplomats must be equipped to handle.

“Speaking, moreover, is generally harder than listening. No responsible person would ask a 3 to speak before an unfriendly crowd at the local university (or at the embassy gates), much less put a 3 in front of a television camera and expect a clear, engaging and cogent discussion of U.S. Middle East policy in Arabic. For that you need a 4, and preferably a 4+ or a 5. So how many of these 4 and 5 level speakers do we have in Arabic? As of August 2004 — 27. At the highest levels (4+ and 5), we have a grand total of eight individuals worldwide.

“This little band cannot possibly cover our need to understand and be understood across 21 embassies and consulates in a region with a population approaching 300 million people, and one, moreover, with very different dialects from east to west. Given that some of our Arabic speakers are inevitably on rotation in Washington or even assigned outside the region, our 27 most fluent Arabic-speaking diplomats equate to barely one per post.

“Of course, so-called Foreign Service Nationals — local professionals who are hired to work in the U.S. embassy in a given country — can provide valuable backup. But there is no substitute for having Americans who can communicate — really communicate — in the local language. The failure to field more diplomats who speak the language gives unhelpful support to the view that the United States just does not take the Arab world seriously.

Arabic verb chart

What Can Be Done About the Lack of Arabic-Speaking Diplomats

In 2005, Jennifer Bremer wrote in the Washington Post: “So how do we get our team up to speed, quickly? There are two ways to field more diplomats with solid Arabic skills in the short term: hire more Americans who already speak Arabic, especially mid-career Arab Americans with real fluency and professional skills, or upgrade our existing stock of 3's by instituting much broader and deeper on-the-job language training, both in Washington and in our embassies ("at post" in Foreign Service-speak).” [Source: Jennifer Bremer, Washington Post, October 16, 2005 Bremer is a member of the business school faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and an adviser to the university's Carolina Center for the Study of the Middle East and Muslim Civilizations. As a Foreign Service officer in Cairo from 1977 to 1980, she earned a level 3 in spoken Arabic. ***]

“The first option sounds promising. But if it were easy to recruit Arab Americans from immigrant and first-generation backgrounds as senior diplomats, surely we would have more than eight fluent Arabic speakers on board by now. We need to keep working hard to attract Arab Americans (and other so-called "heritage speakers" who can enrich our diplomatic corps's cultural and language skills in important regions) into the diplomatic service, but building a diverse Foreign Service has been slow going. Strong disincentives, from poor pay to tight budgets and widespread Arab American doubts regarding U.S. Mideast policy, stand in the way of a rapid buildup in Arab American diplomats. ***

“So how about option No. 2, turning more 3's into 4's? The State Department has a world-famous language training program, the Foreign Service Institute (FSI), staffed by highly trained professionals. Anyone who has reached a 3 in Arabic can get to a 4 with determined study. Even a 2 has a good base to build on. Unfortunately, current policies for language training make it all but impossible to turn 3's into 4's. Upgrading our roster of Arabic speakers would require getting around three obstacles. ***

“First, traditional language training, based on sending officers to full-time language study for extended periods, is expensive. Since Arabic is a difficult language, the FSI figures it takes two years of full-time training to get a committed learner from a simple greeting of " Salaam aleikum" to level 3.The State Department has made a significant commitment to expanding language training, nonetheless. Enrollments in Arabic and other challenging regional languages such as Farsi and Uzbek increased more than 80 percent from 2003 to 2004, from 228 officers to 415. Training averaged only a couple of months per person, though — pretty basic stuff delivered in a hurry for most of the participants, in other words.” ***

Arabic Language Studies Booming at U.S. Universities

According to ICEF Monitor: “The growth in Arabic language studies in the US over the past decade is nothing short of remarkable. Surveys conducted by the MLA in 2006 and 2009 found that interest in studying Arabic changed sharply in the wake of the September 11 attacks of 2001. American student enrolment in Arabic language courses grew by 126.5% from 2002 to 2006 and then again by another 46.3% between 2006 and 2009 – the most recent period for which survey data is available. |~| [Source: International Community Empowerment Foundation (ICEF) Monitor, December 1, 2014 |~|]

Arabic verb chart

“That makes Arabic the fastest-growing area of foreign language study in the US, by far, and, as of the 2009 survey, the eighth most-studied language in America. Also as of 2009, 35,083 college and university students in the US were enrolled in Arabic courses. |~|

““The September 11th attacks in 2001 comprised the second ‘Sputnik moment’ in recent American history, highlighting the importance of studying foreign languages and focusing in particular on Arabic,” says Dr Hezi Brosh, an associate professor of Arabic at the United States Naval Academy. “Pressures on colleges and universities to install or augment Middle Eastern studies have come from all directions. The Department of Defense and other government agencies, businesses and other educational institutions have all expressed the need for more attention in this area. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan created a new demand in federal agencies for speakers of Arabic and other critical-need languages. |~|

“To cope with this growing demand, colleges and universities have created or expanded Islamic, Arabic, and Middle Eastern Studies departments and programmes. As the study of Arabic became more pertinent to Americans than ever before, universities, bolstered with federal funding, inaugurated language flagship programmes.”

Why are U.S. Students Studying Arabic?

According to ICEF Monitor: An article “from NAFSA makes the point that students have different motivations for studying Arabic. Some do so out of an academic interest in the culture or because they have a personal link – a family connection or other – that fires their interest in the language. For the most part, however, students pursue Arabic language studies out of the belief that it will assist them in their careers, whether in national security, with the growing field of multinational corporations active in the region, in academia, or with the non-profit sector. |~| [Source: International Community Empowerment Foundation (ICEF) Monitor, December 1, 2014 |~|]

“NAFSA highlights the example of Cloe Medina Erickson, an American who earned a master’s of architecture degree from Montana State University in 2000, and who subsequently returned to the university to study Arabic. Ms Erickson now lives in Morocco, where she works as an architectural preservationist and where she has also founded a nonprofit focused on community development. “Speaking Arabic was the gateway to my career,” she says. “They appreciated the effort that I made to learn their language, understand their culture, and make an effort to speak with them in their native tongue. I have used my language to converse with our programme partners, write contracts, and meet with the Moroccan government. I could not do the work that I am doing without knowing Arabic.” |~|

“Dr Brosh surveyed over 200 US students enrolled in Arabic studies for a 2013 paper that explored the motivations of Americans to study the language. As the following table reflects, the main factors the students cited were “interest in the language,” “employment,” and “interest in Arab culture/history.” (Dr Brosh notes in his paper, “Because the three reasons ‘Advantage when job hunting,’ ‘Work at a government agency,’ and ‘Work in the Middle East’ are employment-related, I grouped them together as a composite ‘Employment’ [factor].”)

Arabic Becomes Popular in the U.S. in the Early 2000s

In 2003, Sam Dillon wrote in New York Times: “The United States, with much of its military, intelligence and diplomatic energy focused on the Mideast crisis, needs more Arabic speakers, and it is getting them. Scores of colleges and universities have added or expanded Arabic course offerings, and a new study has provided the first broad statistical evidence that more students than ever are enrolling in Arabic classes. [Source: Sam Dillon, New York Times, November 16, 2003 ==]

Arabic verb chart

“But whether the boom will last is another matter. The number of Arabic students remains small. America's new generation of would-be Arabic speakers must show that they can muster the discipline necessary for the long march to fluency. And questions have been raised about the quality of the teaching. ''I have serious concerns about what's going on in some of these classrooms,'' said R. Kirk Belnap, professor of Arabic at Brigham Young University and the director of a federally financed consortium, the National Middle East Language Resource Center. ''There are a lot of counterproductive teaching methods that don't help students learn.' ==

“The new survey, released this month by the Modern Language Association, makes clear that current student interest dwarfs all previous fads in Arabic study, including the boomlet that registered on some campuses at the time of the first gulf war. And separate data the center has collected indicates that students pursuing the language at universities with long-established Arabic departments are showing increased tenacity since the Sept. 11 attacks made its study a national priority.

“The M.L.A. survey collected data on foreign language enrollment from fall 2002 from 780 colleges and universities. It showed that 1.4 million students are studying at least one foreign language, more than in any year since 1972. The survey found that 10,596 students were studying Arabic, compared with 5,505 in 1998, the last time the association collected such figures. Still, Arabic remains outside the mainstream of language study. Fewer than 1 percent of all students enrolled in a foreign language course are studying Arabic. Nine of 10 colleges and universities do not offer a Arabic course, the survey found.

“Even an arcane language like ancient Greek is taught at more than twice as many colleges as Arabic, the survey found, although that is changing. In 1998, only 157 colleges and universities offered Arabic. By 2002, an additional 77 did. Opportunities to learn it are opening faster than for any other language except Spanish.

Problems Teaching Arabic in the U.S.

Sam Dillon wrote in New York Times: ““Growth is creating its own problems. Many schools adding Arabic courses are hiring native speakers as instructors, even if they do not have a degree or teaching experience, and the salaries may be too low to make sure they stay. Immediately after Sept. 11, 2001, the University of North Alabama in Florence began offering a beginning Arabic course. T. Craig Christy, the chairman of the foreign languages department, said that North Alabama hired an Egyptian-born man working at a local import-export company to teach conversational Arabic twice a week. He acknowledged that the school is paying the instructor little. ''Compensation is minimal,'' he said. ''It's more an act of charity by this instructor.'' [Source: Sam Dillon, New York Times, November 16, 2003 ==]

“The course has attracted half a dozen or so students in each of three fall terms, he said. But so far not enough students have expressed interest in second-year Arabic to warrant offering a higher-level course. This suggests that at least at some universities, students are acquainting themselves with Arabic, then dropping out. ==

“Attrition is a factor in the study of any language. Richard D. Lambert, former director of the National Foreign Language Center, a private organization based in Washington, said in a 1992 study that because foreign language requirements were reduced in the 1960's and 1970's, attrition is predictable. ''It can almost be called a natural law,'' Dr. Lambert said. ''In both high school and college, 50 percent of the students at each level drop out at the next level.'' That is, if 100 students sign up to study French I, only 50 students enroll in French II a year later, and 25 students in French III the year after that. ==

Arabic keyboard

“So far, however, recent statistics from the National Middle East Language Resource Center show that attrition among Arabic learners appears to be lower than Lambert's law would predict. At nine universities with long-established Arabic programs — Emory, Harvard, New York University, Princeton, University of California at Los Angeles, Chicago, University of Pennsylvania, University of Utah and University of Washington — 61 percent of students who completed first year Arabic in June 2002 enrolled in second-year courses in the fall, and 63 percent who completed second-year courses enrolled for the third year. ==

“But the persistence could soon create a problem, Dr. Belnap said. The normal next step for a student who has taken three years of Arabic is to study abroad, most frequently in Cairo. But the main advanced Arabic program there, financed by the United States government, would not now be able to accommodate the large numbers of qualified students likely to seek enrollment within a couple of years, he said.''We have a serious bottleneck developing,'' Dr. Belnap said.” ==

Taking an Arabic Class

Robert Lane Greene wrote in Slate.com: “When I walked into Arabic class last week, Karam, my teacher, cheerily asked me how I was doing. I said, "Tamaam, hamdulillah," which means, "Fine, thanks be to God." But I was lying. I'd just spent a full day at work and was sitting down at a desk for two hours of mind-bending grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation. I knew it would be a long night. [Source: Robert Lane Greene, Slate.com, June 9 2005 \~]

“I am not one of those people who dreads the thought of learning a foreign language. While everyone else was partying in high school, I was learning the Spanish past subjunctive and loving it. I studied German, French, and Portuguese in college. I speak decent Russian and have taught myself some half-decent rudimentary Japanese. Languages are usually fun. But Arabic is really killing me.\~\

“Merav is fine with this, though the rest of us are struggling. But the ferociously unfamiliar grammar sets us all adrift. Arabic is a VSO language, which means the verb usually comes before the subject and object. It has a dual number, so nouns and verbs must be learned in singular, dual, and plural. A present-tense verb has 13 forms. There are three noun cases and two genders. Some European languages have just as many forms to keep track of, but in Arabic the idiosyncrasies can be mind-boggling. When Karam explains that numbers are marked for gender—but most numbers take the opposite gender from the word they are modifying—we students stare at each other in slack-jawed solidarity. When we learn that adjectives modifying nonhuman plurals always have a feminine singular form—meaning that "the cars are new" comes out as "the cars, she are new"—I can hear heads banging on the desks around me. I want to do the same. \~\

Arabic verb forms (in German)

“Karam sees the wear and tear on us, and so sometimes we pause and have a cultural chat. Arabic is peppered with a lot of God—even secular Arabs will append insha'allah, "God willing," to almost any statement of intent, as in, "I'll file my story by 3, God willing." Sometimes Karam tries to teach us how to work various niceties like this into daily speech. "Thank you" is usually just shukran. "But," Karam tells us, "that is sort of boring, so if someone gives you food it's nicer to say, 'May your hands be blessed,' or …" This is way too much information for my skill level, so I squeeze my eyes shut and hope that Karam's flourishes don't enter my brain and dislodge something vital, like, "Where is the bathroom?"” \~\

Developing Fluent Arabic Speakers

According to ICEF Monitor: “Roughly speaking, for every five US students of Arabic enrolled in introductory-level courses, there is one student engaged in advanced studies of the language. This suggests that most students have little prior experience with the language, and it also raises the question as to how advanced their skills can become, even in more intensive courses in the US. Some suggest that it will take second-language learners five years of study or more before they are fluent enough to study at the postsecondary level in Arabic. [Source: International Community Empowerment Foundation (ICEF) Monitor, December 1, 2014 |~|]

“In order to further raise the level of fluency among non-native speakers in the US, government agencies and educators are taking new steps to expand Arabic studies at the high school level. Initiatives such as the STARTALK Language Program and The Language Flagship Program are squarely aimed at boosting Arabic studies at the high school level, and therefore better supporting more advanced language studies in postsecondary programmes. It happens that both STARTALK and Language Flagship are also directly supported by national security interests (the National Security Agency and the Department of Defense respectively). |~|

“Government agencies and academic institutions in the US are also collaborating to boost student mobility in a further attempt to improve Arabic language skills among American students. Just over 2,100 American students studied in the MENA region in the year 2000. A decade later, in the 2010/2011 academic year, the number of US students in the region had increased to more than 7,200. |~|

“There are a few factors at work here. Most obviously, the growth in mobility to Arab-speaking states tracks with the underlying growth in Arabic language studies in the US. But increasing numbers of US students heading to the region are also being supported by expanded scholarship programmes as well as developing linkages between academic institutions in the US and those in MENA countries. |~|

Arabic alphabet (in German)

“The Critical Language Scholarship Program (CLS), for example, sends US Arabic-language students to study in Jordan, Morocco, and Oman. Similarly, the Boren Scholarships “provide unique funding opportunities for US undergraduate students to study less commonly taught languages in world regions critical to US interests.” And more institutions are following the lead of Montana State University – which has been active in the region since the mid-1990s – in partnering with local universities for joint programmes or integrated study abroad options. |~|

“In fact, for a growing number of US universities offering Arabic majors, such as Georgetown University, study abroad is an academic requirement. As Elliott Colla, the university’s chair of Arabic and Islamic Studies, told NAFSA, “Our programme is intensive by American standard. Still, we understand that fluency is reached only when students immerse themselves in the culture and society of the languages they are studying.” It seems likely that schools both in the K-12 and higher education levels will look to foster this dramatic growth in Arabic studies in the US, which may in turn fuel US outbound mobility to the MENA region in the years ahead.

Arabic Translators and the War on Terrorism

Skilled Arabic translators have proved to be indispensable in the war on terrorism, helping intelligence and law enforcement agencies sort out nuances of dialect and culture. But often they're caught between two worlds. Reporting from Paris,Sebastian Rotella wrote in Los Angeles Times: “As a crack interpreter for anti-terrorism investigators, "Wadad" fights the war of the words. She deciphers North African dialects, Middle Eastern accents and the French Arabic slang of jail yards and housing projects. She braves the crossfire during marathon interrogations of suspected terrorists who snarl at the presence of a female interpreter or recite Qur’anic verses. She cracks the codes of gunslinger theologians for whom "visiting an aunt" means going to prison and "preparing a marriage" means a suicide attack. [Source: Sebastian Rotella, Los Angeles Times, December 11, 2004 |]

“Wadad's job with a French anti-terrorism agency requires the skills of a linguist, a detective, a historian. It requires bleary-eyed hours transcribing wiretaps and documents. It carries huge responsibility: An interpreter can detect an imminent attack, put an innocent man behind bars, make or break a case. "It's certainly delicate work," she said. "I am completely absorbed by it. I have a passion for it. I am aware of how important it is. I know I don't have the right to make a mistake." |

“In Europe and especially in the United States, anti-terrorism agencies contend with an acute shortage of Arabic-speaking investigators and translators, say veteran European law enforcement officials. As Western security forces strain to confront and comprehend terrorism by Islamic extremists, one of their greatest challenges is the recruitment of skilled, trustworthy linguists. France probably has the biggest and best cadre of linguists, European officials say. Its population of Arabic origin is the continent's largest, drawing on Francophone diasporas from North Africa and Lebanon. Outbreaks of terrorism here in the 1980s and '90s spurred the French to build a robust security apparatus. |

9-11

“The best linguists are bilingual and bicultural from childhood, said Wadad, the French interpreter. "Otherwise, you might understand the words but not the meaning," she said. "You have to understand the dialect, their mentality, their history. If you don't know the two civilizations, it's very difficult. A North African might constantly mention Allah in his conversations. But that's common. It doesn't mean he's a religious extremist." |

“Wadad grew up in a Muslim family speaking Arabic and French. As a rookie, she was first assigned to investigations of organized crime. She shifted to anti-terrorism shortly before Algerian-dominated networks unleashed a campaign of violence against the French in the mid-1990s. In addition to studying regional dialects, Wadad honed her expertise with research on Islam, terrorism and the Middle East. She remains a voracious, critical reader with a quiet self-confidence bred by her mix of street and book knowledge. "There are Arabists in France who are brilliant intellectuals and know a lot, but I think there are things that escape them," she said. "I think if Arabic is not your mother tongue, if you don't read the Qur’an from the perspective of a devout Muslim and try to see it with the mind-set of the time when it was written, you miss things. The academics try to make everything fit into their theories."” |

Problems with Arabic Translators: Overwork, Death Threats, Spies and Inaccuracies

Sebastian Rotella wrote in Los Angeles Times: “"The translators are overworked, underpaid and scared," an Italian official said. In Italy, a North African translator quit a law enforcement job because militants threatened him while he was visiting his homeland. Dutch police recently arrested an intelligence service translator, accusing him of acting as a double agent. This year's deadly train bombings in Madrid revealed overwhelming workloads for translators, delays in listening to and transcribing intercepts, and a lack of specialists with analytical skills or expertise in the many Arabic dialects. [Source: Sebastian Rotella, Los Angeles Times, December 11, 2004 |]

“"There are a lot of bad translators," said Alain Grignard, a veteran commander of Belgium's federal police and one of the few senior investigators in Europe who speak fluent Arabic. "The real solution is to team up translators with police analysts who know some Arabic. It's very demanding. You have to understand the religious and historical references. The Islamists talk about events in the Middle Ages as if they had happened yesterday." Grignard cited a public statement by Osama bin Laden in which the Al Qaeda leader compared President Bush to Hulagu Khan, a Mongol chieftain and grandson of Genghis Khan who conquered Baghdad in 1258. |

“Harried European and U.S. authorities sometimes enlist the help of Arab spy agencies, particularly from Egypt, Jordan and Morocco, officials say. But that risks security breaches and manipulation. Similarly, a tendency to recruit non-Muslim Arabs can backfire because some Lebanese Christians or Egyptian Coptics might be influenced by religious resentments, Grignard said. |

Arabic on a computer

“Challenges persist, a senior French anti-terrorism official said. "It's harder to get Pakistani interpreters," he said. "And with Iranians it is very difficult, because their intelligence service is so good at infiltration." “The Italian proverb "Traduttore, traditore" ("Translator, traitor") apparently became reality in the Netherlands. In September, police arrested a translator for the AIVD spy agency. He has been identified only as Outmar ben A., 34, a Dutch citizen of Moroccan descent. He had left a post at the immigration service to work for the intelligence agency half a year before his arrest, according to AIVD spokesman Vincent van Steen. |

“He fell under suspicion after police found classified documents in Utrecht homes raided in connection with a suspected bomb plot, Van Steen said. Outmar allegedly tipped off the suspects, enabling them to get rid of explosives before the roundup. Police want to determine whether Outmar was already in league with extremists when he was hired, Van Steen said. The case recalls the arrest last year of a Syrian-born translator for the U.S. Air Force who had been assigned to the detention camp at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, and was accused of spying. |

“Faulty translations can also cause havoc. The senior French official cited a hijacking scare last year that led to the cancellation of half a dozen flights from Paris to Los Angeles during the Christmas holidays. The alert resulted partly from a U.S. intercept of a communication in Arabic. After examining the original language, French experts concluded that their U.S. counterparts had interpreted it to seem more menacing than it really was, the senior official said. "The translation was inaccurate from A to Z," the official said. "And we showed this to the Americans." |

Use of Arabic Translators in Police Work

Sebastian Rotella wrote in Los Angeles Times: ““Names on the flights' passenger lists that resembled names on terrorism watch lists heightened worries about a plot. But U.S. and French agents found no passengers with ties to extremism. Although U.S. officials acknowledge that there were differences of opinion between French and American investigators and even among U.S. agencies, they have said that the cancellations were based on well-founded concerns. [Source: Sebastian Rotella, Los Angeles Times, December 11, 2004 |]

“The West's varying approaches to spelling Arabic names can cause confusion. A Jordanian cleric jailed in London on charges of being Al Qaeda's leading ideologue in Europe is known alternately as Abu Qatada and Abu Katada. The terrorist network's name has been written as Al Qaeda, Al Qaida and Al Qida. "You can identify the wrong person as a terrorist, or fail to identify a terrorist, because of a single letter," the senior French official said. "It can't be done rigidly. It can't be done by a computer." |

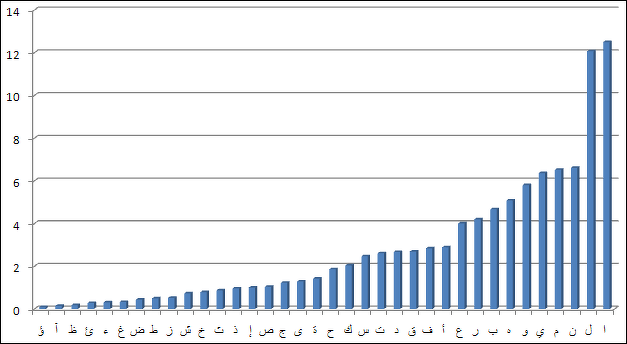

frequency distribution of Arabic letters sorted according to frequency

“The human factor is crucial. Intercepts show that extremist groups keep up their fervor with long, sometimes bloodcurdling, conversations about holy war. Translators have to distinguish between mere bluster and bona fide plotting. They listen for key code words and activities, such as the writing of wills and purification rituals, that may precede "martyrdom" attacks. |

“The capture in Milan, Italy, of an accused mastermind of the Madrid bombings featured round-the-clock teamwork between detectives and translators this year. After Italian police planted a listening device in his hide-out, the bug caught fugitive Rabei Osman Sayed Ahmed admitting involvement in the train bombings and, according to a transcript dated May 28, his exultation as he watched an Internet video of the beheading of Nicholas Berg, an American hostage in Iraq. "That's the way, Allah is great, Allah is great, Allah is great.... Go to Hell, enemy of God, kill him ... cut his head off," Ahmed growled amid sounds of the slaying. "If it was me, I'd have burned him to show him that this is what hell is like." |

“The surveillance called for a highly skilled interpreter, an Italian investigator said, because it was more challenging than a telephone intercept. "It's much harder because you have multiple people talking, more noise," the investigator said. "Many translators aren't good at in-house wiretaps." Police became alarmed as Ahmed and a suspect in Brussels vowed to die as martyrs. In the hide-out and on the phone, they alluded to "the operations advancing," an extremist "in movement" and "the situation tightening." With the help of interpreters, police decided the time had come to make arrests.” |

Why a Muslim Becomes an Anti-TerroristArabic Translators

Sebastian Rotella wrote in Los Angeles Times: “Wadad describes herself as a Muslim but has distanced herself from the rituals of the religion. She has had a rare, up-close opportunity to study dozens of Islamic extremists over the years. They often memorize the Qur’an without really understanding it, pulling snippets out of context to justify criminality and mayhem, she said, adding that in some cases, terrorism seems more about status and glory than faith. “"Many are blinded, a few are manipulators," Wadad said. "I have met one who really, really impressed me. A chief. He really knew the Qur’an. He was very calm. He had a high intellectual level. He spent the interrogation responding with verses of the Qur’an. He was a big, big manipulator. And that made him very dangerous. He was convicted, she said. [Source: Sebastian Rotella, Los Angeles Times, December 11, 2004 |]

“The cultured, well-dressed Wadad has a smile tinged with melancholy. A personal factor influenced her choice of law enforcement over less harrowing, more lucrative assignments in the private sector: Her family has suffered the brutality of extremist violence. | "Killing innocents is unacceptable," she said. "Whether one victim or 1,000, it's the same. It's abominable." |

“It's common for translators to have a sense of mission. A veteran British investigator recalled that a police translator told him she was motivated by gratitude because surgeons in Britain had cured her immigrant father of a serious ailment with an operation unavailable in his homeland. |

frequency distribution of Arabic letters sorted according to Unicode values

“Because many European investigators speak limited or no Arabic, they come to depend on and admire their translators. One law enforcement official marveled at the edgy dedication of a North African translator that led to a confrontation with a suspect. During a judicial hearing, the suspect used a common tactic and challenged the translation, denying that a voice on a wiretap was his. The translator snapped back: "I've been listening to your voice for two years. Don't tell me that's not your voice!" |

“It is likely to take a generation for anti-terrorism agencies to groom significant numbers of Arabic-speaking investigators, just as NATO governments eventually developed a pool of Russian linguists during the Cold War, officials said. Despite the demand and a well-intentioned desire to promote minorities, the process cannot be rushed, officials said. |

“Would-be police officers and intelligence agents of Arabic origin encounter problems that are reminiscent of affirmative action debates in the United States, said Grignard, the Belgian police commander. Applicants may have relatives or friends with links to extremism or crime. Moreover, anti-terrorism investigators with Arabic backgrounds endure unique psychological pressures, he said. |

“"There is always a sense of distrust on both sides," Grignard said. "They think that the routine vetting that is done for all terror cops somehow singles them out because of their ethnicity.... They feel great isolation. They are caught between the two worlds." “For the moment, Wadad has job security. Her colleagues say she is at the top of her craft. Even hidebound fanatics have come to appreciate her. "There have been a few rare cases when a suspect did not want me to be the interpreter because I am a woman," she said. "They started out by saying they refused to talk. But then they were told, 'Look, it's either this interpreter or none at all.' So they agreed. And with one guy in particular, by the end it was clear that he was reassured, he didn't resent me anymore. He knew I wasn't there to be against him. I was there to do my job." |

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994). “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, BBC, Al Jazeera, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018