ASSYRIANS

Sargon I The Assyrians established an empire in Mesopotamia about 700 years after departure of the Babylonians. They ruled Mesopotamia and much of the Near and Middle East from 883 to 612 B.C. At its height the Assyrian empire was centered in Nineveh, Iraq and encompassed what is now Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, and Egypt and large parts of Turkey and Iran. They created the first international empire where trade, religion and artistic ideas flowed freely.

The Assyrians and their primary God Ashur are named after Ashur, a city in northern Iraq that lay at the center of their homeland. They were initially ruled by Babylonians and were strongly influenced by Babylonian culture. Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: For centuries, the Assyrians’ fortunes ebbed and flowed. But early in the first millennium B.C., a series of formidable kings ushered in a prolonged period of prosperity and expansion. What had once been a relatively insignificant city-state came to control all of Mesopotamia, as well as parts of Egypt, the Levant, Anatolia, and Arabia. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, Features July/August 2024]

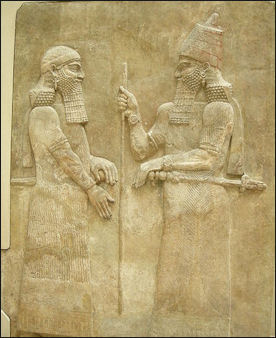

Along with the military might elaborated on below, the Assyrians were renowned for their finely crafted sculptures and reliefs, their collection of literature and scientific knowledge, and the opulence of their cities. This was especially true of Nineveh.

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Assyria: The Rise and Fall of the World's First Empire” by Eckart Frahm (2023) Amazon.com;

“Assyrian Empire: A History from Beginning to End” by History Hourly (2019) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Assyria” by Eckart Frahm (2017) Amazon.com;

“I Am Ashurbanipal: King of the World, King of Assyria” by Gareth Brereton (2018) Amazon.com;

”The Final Sack of Nineveh: The Discovery, Documentation and Destruction of Sennacherib's Palace at Nineveh, Iraq” by John M. Russell (1998) Amazon.com;

“Climate, Environment and Agriculture in Assyria: In the 2nd Half of the 2nd Millennium BCE” (Studia Chaburensia) by Herve Reculeau (2011) Amazon.com;

“The History of Babylonia and Assyria” by Hugo Winckler (1892) Amazon.com;

“The First Great Powers: Babylon and Assyria” by Arthur Cotterell (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Assyrian” Novel by Nicholas Guild (1987) Amazon.com;

“The Crimson Field” by Rosie Malek-Yonan (2005) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Assyria: A Very Short Introduction” by Karen Radner (2015) Amazon.com;

“The Might That Was Assyria” by H. W. F. Saggs (1984) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Assyria” by James Baikie (2022) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamia: an Enthralling Overview of Mesopotamian History (2022) Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamia: a Captivating Guide (2019) Amazon.com;

“A History of the Ancient Near East” by Marc Van De Mieroop (2003) Amazon.com;

Assyrian Ferocity and Violence

The Assyrians were known for their fighting skill and brutality. The Old Testament describes Assyrian kings and armies that “laid waste to nations” and brought “calculated frightfulness.” The Assyrians are referred to on numerous occasions in the Bible. For the most part they and their kings are condemned for their cruelty and despotism. The prophet Isaiah assails the “the king of Assyria’s boastful heart and his arrogant insolence.” The prophet Nahum accuses another Assyrian king of “unrelenting cruelty.” The second Book of Kings warns that “the kings of Assyria have exterminated all the nation, they have thrown their gods on the fire.”

There are some who feel that Assyrians have gotten and undeserved bad rap. They were conquerors, yes, but so were a lot of other successful ancient empires. In the territories they ruled over the promoted peaceful trade and religious tolerance and employed skillful diplomacy and effective propaganda. They were able administrators and built massive structures that "were awesome in size and appearance" and "meant to impress the visitor with the power of the king."

“All empires depend upon at least a threat of violence, but the Assyrians are particularly bloodthirsty,” Michael Danti of the University of Pennsylvania told Archaeology magazine. “If you rebel against them, they might burn your city down, take away your population, and execute your military leaders. If you sign a treaty with the Assyrians and break it, they annihilate you most of the time. Even by ancient standards, it’s pretty brutal.” [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, Features July/August 2024]

Early Assyrian History

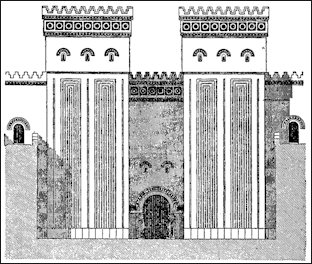

Palace of Khorsabad The Assyrians emerged around 2000 B.C., late by Mesopotamian terms. Around 1400 B.C., they ousted the invaders that occupied their land. Then they extended their rule northward. They established themselves as a regional power in 11th century B.C.

The Assyrian Empire was initially based in Ashur, which at its height was town of perhaps 30,000 people. Ashur lied at the center of strategic trade routes between Babylon, Turkey and Syria. It was the envy of invaders. To hold the city the Assyrians had to became strong and militarily and skilled diplomatically. The Assyrians learned to how make iron weapons and use chariots from the Hittites. They established a military state that drew strength and economic clout from conquest. They organized their society around warfare and boasted of their conquests to strike terror into their enemies and prey.

The local people of Ashur were more interested in making money than in politics and conquering until around 900 B.C. when the city’s trade routes were threatened by neighboring states and powerful families decided to build an army to protect those routes. The army that was established was quite fordable. Rival states were easily held off and victories gave the Assyrian rulers confidence and a taste for power and conquest. The capital of Assyria moved from Nimrud to Nineveh in 863 B.C.

Aaron Skaist wrote in the Encyclopaedia Judaica: The emergence of Assyria as a major Near Eastern power can best be dated to the accession of Ashur-uballi I (c. 1365–1330), who first claimed the title "king of the land of Ashur." Ashur was the name of the god held in special reverence by the Assyrians, and of the ancient city built by his worshipers on the Tigris. For a thousand years before Ashur-uballi 's accession, the city had been ruled by a long succession of foreign masters as a minor province, in succession, of the great empires of Akkad, Ur, Eshnunna, Shubat-Enlil, and Washukkanni. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

In all this millennium, Ashur had enjoyed the status of an independent city-state only once, in the brief interlude following the fall of Ur (c. 2000–1850). At that time its citizens displayed their vitality by their extensive and sophisticated trading operations deep into Anatolia; many thousands of "Cappadocian" tablets, inscribed in the Old Assyrian dialect, have left an enduring record of this trade. However, even in periods of political subservience, the Assyrians maintained a clear sense of their own identity. Foreign rulers were given native genealogies or, by an equally pious fiction, local governors were elevated to royal status by the later historiography. The Assyrian historians should not, however, be accused of willful distortion; rather, they were giving formal expression to a very real sense of continuity which centered on the worship of Ashur, the deity from whom their city took its name. They thus provide an instructive parallel to the Israelite experience as canonized in the Bible. In both instances, it was the reality of an unbroken religious tradition which permitted an ethnic group to lay claim to the memories or monuments surviving from the Middle Bronze Age and to link them to later political institutions.

List of Rulers of Assyria

Old Assyrian dynasty:

Shamshi-Adad: 1813–1781 B.C.;

Dynasty of Mari: Zimri-Lim: 1775 B.C.

Middle Assyrian dynasty:

Ashur-uballit I: 1365–1330 B.C.;

Enlil-nirari: 1329–1320 B.C.;

Adad-nirari I: 1307–1275 B.C.;

Tukulti-Ninurta I: 1244–1208 B.C.;

Ashur-dan I: 1179–1134 B.C.;

Tiglath-pileser I: 1114–1076 B.C.;

Ashur-bel-kala: 1073–1056 B.C.

Neo-Assyrian dynasty:

Ashurnasirpal II: 883–859 B.C.;

Shalmaneser III: 858–824 B.C.;

Shamshi-Adad V: 823–811 B.C.;

Adad-nirari III: 810–783 B.C.;

Shalmaneser IV: 782–773 B.C.;

Ashur-dan III: 772–755 B.C.;

Ashur-nirari V: 754–745 B.C.;

Tiglath-pileser III: 745–727 B.C.;

Shalmaneser V: 726–722 B.C.;

Sargon II: 721–705 B.C.;

Sennacherib: 704–681 B.C.;

Esarhaddon: 680–669 B.C.;

Ashurbanipal: 668–627 B.C.;

Ashur-etel-ilani: 626–623 B.C.;

Sin-shar-ishkun: 622–612 B.C.;

Ashur-uballit II: 611–609 B.C.;

Mesopotamia United

[Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. "List of Rulers of Mesopotamia", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/meru/hd_meru.htm (October 2004)

Early Assyrian Period: Rise of the Assyrians

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The ancient city of Ashur (Assur) was located on the west bank of the river Tigris in northern Mesopotamia. Although it had controlled an extensive trading network in the early second millennium B.C. and formed a core area of the empire of Shamshi-Adad I (r. 1813–1781 B.C.), the city had slipped into the shadows in the following centuries. [Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. "Assyria, 1365–609 B.C.", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, originally published October 2004, last revised April 2010 metmuseum.org \^/]

“After several centuries of obscurity and even loss of independence from around 1400 B.C. under the powerful northern Mesopotamian state of Mitanni, Assyria's fortunes revived in the reign of Ashur-uballit I (1365–1330 B.C.). From his capital at Ashur, Ashur-uballit extended Assyrian control over the rich farming lands of Nineveh and Arbela to the north. The new conquests were consolidated by succeeding kings and, under Adad-nirari I (r. 1307–1275 B.C.), the remnants of the state of Mitanni were conquered and Assyrian control stretched to the Euphrates and the borders of the Hittite empire.” \^/

Aaron Skaist wrote in Encyclopaedia Judaica: The Assyrians got their chance when Mitannian power began to collapse in the middle of the 14th century, under the combined impact of Hittite pressure and the progressive disengagement from Asiatic affairs by the Egyptian pharaohs of the Amarna period, since Egypt, as the principal ally of Mitanni, was the only effective counterweight to Suppiluliumas' ambitions. Ashur-uballi took advantage of the situation to throw off the Hurrian overlordship of Mitanni. Disdaining that of Kassite Babylonia which claimed to have inherited it, he began to negotiate on a footing of equality with all the great powers of his time, as well as to show the Assyrian mettle in battle, chiefly with the Kassites. [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

Assyrians, Babylonians and Kassites

Morris Jastrow said: “The first result of the rise of Assyria was to limit the further extension of Babylonia. The successors of Hammurabi, partly under the influence of the loftier spirit which he had introduced into the country during the closing years of his reign, partly under the stress of necessity, became promoters of peace. Instead of further territorial expansion we find the growth of commerce, which, however, did not hinder Babylonia itself from becoming a prey to a conquering nation that came (as did the Sumerians) from the mountainous regions on the east. Native rulers are replaced by Kassites who, as we have already indicated, retain control of the Euphrates Valley for more than half a millennium. It is significant of the strength which Assyria had meanwhile acquired, that it held the Kassites in check.

"Alliances between Assyrians and Kassites alternated with conflicts in which, on the whole, the Assyrians gained a steady advantage. But the Assyrian empire also had its varying fortunes before it assumed, in the 12th century, a position of decided superiority over the south. The chief adversaries of the Assyarian rulers were the Hittite groups, who continued to maintain a strong kingdom in north-western Mesopotamia. In addition, there were other groups farther north in the mountain recesses of Asia Minor, which from time to time made serious inroads on Assyria, abetted no doubt by the Hittites or by the Mitanni elements in Assyria, which had probably not been entirely absorbed as yet by the Semitic Assyrians. [Source: Morris Jastrow, Lectures more than ten years after publishing his book “Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria” 1911]

Aaron Skaist wrote in Encyclopaedia Judaica: Indeed, the fortunes of Assyria and Babylonia were henceforth closely linked; dynastic intermarriages and treaties alternated with breaches of peace and adjustments of the common border in favor of the victor. A synchronistic king list recorded these contacts in the first systematic attempt to correlate the histories of two discrete states before the Book of Kings (which made the same attempt for the Divided Monarchy). This synchronistic style was cultivated by the Assyrian historians along with other historical genres, while the court poets created a whole cycle of epics celebrating the triumphs over the Kassites. The Assyrian kings, portrayed in heroic proportions, figured as peerless protagonists of the latter, and generally claimed the upper hand in these encounters. However, a deep-seated respect for the older culture and religion of Babylonia, which they regarded as ancestral to their own, constrained them from following up on their advantage at first.[Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

This restraint was dropped by Tukulti-Ninurta i (c. 1244–1208 B.C.), one of the few intriguing personalities in the long line of Assyrian kings who were more often so true to form that they are barely distinguishable one from another. So far from respecting the sanctity of Babylon, he took its defeated king into Assyrian captivity together with the statue of Marduk its god, razed the walls of the city, and assumed the rule of all of Babylonia in his own person. At home, he claimed almost divine honors and, not content with an extensive building program at Ashur, he moved across the Tigris to found a whole new capital, which he named after himself. But in all this he aroused increasing enmity, both for the sacrilege against Babylon and for the heavy exactions of his military and building programs. A reaction set in and, led by the king's own son and successor, the more conservative party imprisoned the king in his new capital and set fire to it. The fame of Tukulti-Ninurta was such that garbled features of his reign are thought to be preserved in both biblical and Greek literature. Thus he is supposed (by some scholars; but cf. above, on Narâm-Sin) to have suggested the figure of Nimrod, the conqueror and hunter of Genesis 10; the "King Ninos" who built "the city of Ninos," according to one Greek legend; and the Sardanapalos who died a fiery death in his own city, according to another. Separating fact from legend, it is clear that his death ushered in a temporary eclipse of the newly emergent Assyrian power that was destined to last for almost a century.

See Separate Articles: OLD BABYLONIANS: THEIR HISTORY, ACHIEVEMENTS, RISE AND FALL africame.factsanddetails.com ; KASSITES: THE MAIN MESOPOTAMIAN POWER AFTER THE FIRST BABYLONIAN EMPIRE africame.factsanddetails.com

Middle Assyrian Period

“Nonetheless, apart from the loss of Babylonia, the Assyrian empire did not disintegrate. Under Tiglath-pileser I (r. 1114–1076 B.C.), campaigns were conducted north as far as Lake Van and the king even journeyed to the Mediterranean, where he received royal gifts. Much campaigning by Tiglath-pileser and succeeding kings was directed against Aramaean pastoralist groups in Syria, some of whom where moving against Assyrian centers. By the end of the second millennium B.C., the Aramaean expansion had resulted in the loss of much Assyrian territory in Upper Mesopotamia.” \^/

The Middle Assyrian may have been affected by the Late Bronze Age collapse. The Late Bronze Age collapse refers to widespread societal and state collapse during the 12th century B.C. associated with mass migration, and the destruction of cities and believed tohave been caused of exacerbated by environmental change. The collapse affected a large area of the Eastern Mediterranean and the Near East, particularly Egypt, eastern Libya, the Balkans, the Aegean, Anatolia, and, to a lesser degree, the Caucasus. It was sudden, violent, and culturally disruptive for many Bronze Age civilizations, and it brought a sharp economic decline to regional powers, notably ushering in the Greek Dark Ages. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Late Bronze Age collapse triggered the collapse of Mycenaean Greek civilization and the Hittite Empire of Anatolia and the Levant. The Middle Assyrian Empire in Mesopotamia and the New Kingdom of Egypt survived but were weakened, Other cultures such as the Phoenicians enjoyed increased autonomy and power with the decline of Egyptian, Hittite and Assyria military presence in West Asia.

Aaron Skaist wrote in Encyclopaedia Judaica: The Assyrian eclipse starting about 1200 was only one phase, and a relatively mild one at that, of the upheaval that marked the end of the Bronze Age throughout the Near East, and whose principal cause was the wave of mass migrations that engulfed the entire area. Tiglath-Pileser I (c. 1115–1077 B.C.) reestablished Assyria's military reputation and, while respecting the common frontier with Babylonia in the south, and holding off the warlike mountaineers on Assyria's eastern and northern borders, laid the foundations for her "manifest destiny" — expansion to the west. An Assyrian campaign down the Tigris to the Babylonian frontier and then up the Euphrates and Khabur rivers to rejoin the Tigris north of Ashur had become an annual event by the time of Tukulti-Ninurta II (890–884); the petty chieftains of the Arameo-Hittite lands west of Assyria learned to expect swift retribution if they did not pay the tribute exacted on these expeditions. The "calculated frightfulness" of Ashurnasirpal II (883–859) was graphically impressed on his visiting vassals by the reliefs he carved on the walls of his new palace at Kalhu (biblical Calah). [Source: Aaron Skaist, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2005, Encyclopedia.com]

See Separate Article: LATE BRONZE AGE COLLAPSE africame.factsanddetails.com

Middle Assyrian Dynasty Rulers: Ashur-uballit I: 1365–1330 B.C.; Enlil-nirari: 1329–1320 B.C.; Adad-nirari I: 1307–1275 B.C.; Tukulti-Ninurta I: 1244–1208 B.C.; Ashur-dan I: 1179–1134 B.C.; Tiglath-pileser I: 1114–1076 B.C.; Ashur-bel-kala: 1073–1056 B.C.

Neo-Assyrian Period

Sargon II According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: From the ninth to the seventh centuries B.C., Assyria prospered under a series of exceptionally effective rulers who expanded its borders far beyond the northern plains. Beginning in the ninth century B.C., the Assyrian armies controlled the major trade routes and dominated the surrounding states in Babylonia, western Iran, Anatolia, and the Levant. The city of Ashur continued to be important as the ancient and religious capital, but the Assyrian kings also founded and expanded other cities. Ashurnasirpal II (r. 883–859 B.C.) established Nimrud (ancient Kalhu) as his capital and undertook impressive building works, including the Northwest Palace. During Ashurnasirpal's rule, Assyria recovered much of the territory that it had lost around 1100 B.C. at the end of the Middle Assyrian period. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, revised April 2010 metmuseum.org\^/]

“Shalmaneser III (r. 858–824 B.C.) succeeded his father, Ashurnasirpal, as king and attempted to consolidate earlier military successes both to the west in Syria and the Levant and to the north in Anatolia. After a series of kings, Sargon II (r. 721–705 B.C.) founded Khorsabad (ancient Dur Sharrukin), where he built a great palace. Sargon appears to have seized the throne in a violent coup and, after dealing with resistance inside Assyria, spent much of his rule in battle. He was succeeded on the throne by his son Sennacherib (r. 704–681 B.C.), who chose the ancient city of Nineveh as his capital. Here he built the palace, named the "Palace without Rival," and created a vast library. During Sennacherib's rule, the city of Babylon was captured and sacked as well as the city of Lachish in Judah, an incident recorded in the Bible. After Sennacherib was assassinated by two of his sons, another son, Esarhaddon (r. 680–669 B.C.), came to the throne. He extended Assyrian activity into Egypt, capturing Memphis in 671 B.C., but died en route to a second campaign in Egypt in 669 B.C. Ashurbanipal (r. 668–627 B.C.) succeeded his father as king and during his reign attacked Egypt, Babylonia, and Elam in western Iran.. \^/

“Assyria was at the height of its power, but persistent difficulties controlling Babylonia would soon develop into a major conflict. At the end of the seventh century, the Assyrian empire collapsed under the assault of Babylonians from southern Mesopotamia and Medes, newcomers who were to establish a kingdom in Iran. Nimrud was destroyed twice, first in 614 and again in 612 B.C. In that final year, Ashur and Nineveh also fell, and Assyrian rule in the Near East came to an end.” \^/

Neo-Assyrian Dynasty Rulers: Ashurnasirpal II: 883–859 B.C.; Shalmaneser III: 858–824 B.C.; Shamshi-Adad V: 823–811 B.C.; Adad-nirari III: 810–783 B.C.; Shalmaneser IV: 782–773 B.C.; Ashur-dan III: 772–755 B.C.; Ashur-nirari V: 754–745 B.C.; Tiglath-pileser III: 745–727 B.C.; Shalmaneser V: 726–722 B.C.; Sargon II: 721–705 B.C.; Sennacherib: 704–681 B.C.; Esarhaddon: 680–669 B.C.; Ashurbanipal: 668–627 B.C.; Ashur-etel-ilani: 626–623 B.C.; Sin-shar-ishkun: 622–612 B.C.; Ashur-uballit II: 611–609 B.C.; Mesopotamia United

Assyrian Empire

The Assyrians destroyed the fortified town of Lachish in Judea after a long siege in 701 B.C. They threatened tribes on the Iranian plateau and overwhelmed the Nubian rulers of Egypt. By the 7th century the Assyrians had established the largest empire in the ancient world. Around 700 B.C. Ninevah was regarded as the largest city on the world. Sennacherob’s palace was among the grandest in the world.

The greatest period of Assyrian conquest took place after the Hittite and Egyptian Empires weakened and lost their grip of power over Syria and Palestine. By 728 B.C., the Assyrians had established an empire that stretched from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean.

The Assyrian Empire was at its height from 668 to 627 B.C. Conquered territories were forced to pay tribute to the Assyrian court. To prevent rebellions, the Assyrians deported thousands of captives to the ancient Assyrian homelands north of Akkad and installed governors in conquered regions.

The Assyrians arguably created the world’s first multi-cultural empire. They brought a number of different ethnic groups into the kingdom. Among their rivals were the Urartians, a people that flourished in the mountainous highlands around Lake Van from the late 9th century to the early 6th century B.C. They borrowed heavily from the Assyrians, plundered their neighbors for cattle and prisoners and were one of Assyria’s main rivals. After a violent and mysterious collapse, their kingdom later became the homeland of the Armenians.

Assyrian Attack on Jerusalem and the Lost Tribes of Israel

The revived Assyrian empire, conquered Israel’s northern empire in 722 B.C. After the prophet Hosea predicted that "The calf of Samaria shall be broken into pieces; for they have sown the wind, and the shall reap the whirlwind," the Assyrian king Tiglath-pilese III sacked Damascus and invaded northern Israel. In 722 B.C. northern Israel was conquered by Tiglath-pilese III's successor Shalmanseser V. Sargon recorded: "The city of Samaria I besieged. I took. I carried away 27,290 of the people that dwelt therein."

Sennacherib (705 to 681 B.C.), the Assyrian ruler of Ninevah, launched an unsuccessful siege of Jerusalem in 701 B.C. The siege was cut short, according to the Bible, by intervention by angels. An inscription on a statue found in the doorway of Sennacherib’s throne room recounts a story of bribery from the Bible, the first known independent written account corresponding to a story in the Bible.

According to Assyrian empire records, Israel was a powerful kingdom that posed a threat to Assyrian control of the region. One inscription described an army by Ahab, the husband of biblical Jezebel, as possessing 2,000 chariots, a formidable number at that time. When Israel was conquered by the Assyrians, Israelite chariot units were incorporated into the Assyrian army.

The northern kingdom of Israel was occupied by 12 tribes, who were said to have descended from the Patriarch Jacob. Ten of these tribes — the Reuben, Gad, Zebulon, Simeon, Dan, Asher, Ephraim, Manasseh, Naphtali and Isaachar — became known as the Lost Tribes of Israel when they disappeared after northern Israel was conquered by the Assyrians.

In accord with Assyrian policy of deporting the local population to prevent rebellions, the 200,000 Jews living in the northern kingdom of Israel were exiled. After that nothing was heard from them again. The only clues in the Bible were from II Kings 17:6: "...the king of Assyria took Samaria, and carried Israel away to Assyria, and placed them in Halah and in Habor by the river Gozan, and in the cities of the Medes." This puts them in northern Mesopotamia.

See Separate Article: CONQUEST OF THE JEWISH KINGDOMS BY ASSYRIA africame.factsanddetails.com

Jehu king of Israel submitting to Shalmaneser III of Assyria

End of the Assyrians

The Assyrians eventually overextended themselves as the empire became mired in corruption and cities within the empire came under attack from the Babylonians and other rivals. Recently a clay table written by an official for the Assyrian leader Mannu-ki-Labbali---who is making a desperate cry for reinforcements as he is being besieged by a Babylonian force at the ancient city of Tushan before it is sacked, plundered and burned---was unearthed by a team lead by Cambridge archaeologist John MacGinnis working at Tushan, a rich trading city under the Assyrians located near Diyarbakir in present-day Turkey.

In the 30-line letter, a city treasurer in charge of raising an army to defend the city, despairs over a lack of equipment and manpower to stave off the attack. Speaking for Mannu-ki-Labbali the author of tablet described how coppersmiths, blacksmiths, bow-makers and arrow makers---necessary to keeping an army maintained---have fled the city, “Not one of them is here!” he laments, “How can I command?” he also lists shortages of horses, chariots, bandage boxes and containers. The letter ends with an anguished cry: “No one will come out of it! No one will escape. I am done!” Some historians regard the fall of Tushan as the beginning of the end of the Assyrian empire and if nothing else it shows how unprepared the Assyrians were for attacks by rivals.

The Assyrians were defeated by an alliance of Babylonians to south and Medes (former vassals of the Assyrians), Cimmerians (sometimes confused with Scythians) and Chaldeans from the Iranian plateau who besieged and destroyed Nimrud and the Assyrian capital of Nineveh, burning it to the ground.

The Medes, a people from Iran, laid siege on Ashur in 614 B.C. After a long standoff they managed to force the city gates open. Medes fighters fought hand and hand with city guards in the narrow streets. In 612 B.C. they took Nimrud. In 606 B.C. the Assyrian empire collapsed.

Neo-Baylonians Defeat the Assyrians and Egyptians

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “Not all of the old Assyrian empire bowed to Babylon. A young Assyrian prince was made king and an invitation was sent to Pharaoh Necho of Egypt to join in stopping the growth of the new Babylonian empire. As Necho moved northward to join his allies, Josiah, perhaps in an attempt to protect Judah from both Assyrian and Egyptian control, attempted to stop him and was killed in the battle of Megiddo. Necho proceeded into Syria and Josiah's son Shallum, or Jehoahaz (possibly his throne name), took the throne, supported by the free men of Judah. Within three months he was deposed by Necho and taken as a hostage to Egypt. His brother Eliakim was appointed king and his name changed to Jehoiakim. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org]

“The Babylonian army, led by Nabopolassar's son Nebuchadrezzar (the Nebuchadnezzar of the Bible), defeated the Assyrians and Egyptians at Carchemish in 605. Fleeing Egyptians were pursued to their own borders and only saved from invasion by the death of Nabopolassar which necessitated Nebuchadrezzar's return to Babylon. He was crowned king in April, 604.

“In Judah, Jehoiakim, having promised allegiance to Babylon, retained the crown. He was an unpopular ruler and Jeremiah makes reference to his extravagance in building a new summer palace at Bethhaccerem (Ramat Rahel), a hill site a few miles south of Jerusalem.7 Jeremiah also refers to the brutal and tyrannical role that Jehoiakim played, thus suggesting that he was anything but esteemed.

“The Egyptian-Babylonian power struggle had not been completely settled and in 601 the two nations met again. Apparently the battle was a stalemate, and Nebuchadrezzar returned to Babylon to strengthen his forces. Possibly the failure of Nebuchadrezzar to win a decisive victory encouraged Jehoiakim to make a fatal error and rebel against Babylon. At the time, Nebuchadrezzar was engaged in a frontier struggle and it was not until late in 598 that Babylonian armies moved on Jerusalem. During that same month Jehoiakim died, passing his problems to his 18-year-old son Jehoiachin.

Fall of Nineveh and its Description in the Bible

Nineveh was sacked in 612 B.C. by a coalition of Babylonians from the south and Medes from the east, two long-standing enemies and former subjects of the Assyrians. It was an event from which the Assyrians would never fully recover. Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “For three years Ashurbanipal's successor held the Assyrian throne and at his death Sin-shar-ishkin became king. In the summer of 612, Nabopolassar, a Chaldean leader, aided by Medes and northern nomads, attacked, looted and destroyed Nineveh, an event that marked the crumbling of the last vestiges of power in Assyria and established the foundations for the Neo-Babylonian Empire. There is some evidence that the defeat of Nineveh was the occasion of rejoicing in Judah, although the Assyrians established a new capital at Harran. Within a few years Harran was conquered by the Medes. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org]

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: Nineveh’s ultimate demise at the hands of the Babylonians and the Medes was exceptionally violent, perhaps payback for the treatment they had suffered as subjects of the Neo-Assyrians. “It’s not about just defeating the Assyrians,” archaeologist Michael Danti of the University of Pennsylvania told Archaeology magazine . “They want to stamp them out so that they can never rise from the ashes again.” Evidence of this catastrophic engagement is ubiquitous around the city, especially within Nineveh’s Halzi Gate, where parts of the population came to either defend the city or to flee it. “There, as at other areas, we found bodies of women, children, and older people killed on the spot in 612 B.C.,” says Marchetti. “The ferocity of that attack is clear. There’s a carpet of bodies that is an impressive reminder of what warfare was like at the time.” [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, Features July/August 2024]

Since 2019, archaeologists have begun to unearth evidence showing that, in fact, Nineveh was partially rebuilt in the years after its vicious destruction. But neither the city nor the Assyrians would regain their former glory. Now, as international teams once more rebuild some of Nineveh’s iconic monuments, renewed archaeological investigation is lifting the site into prominence again. The Mashki and Adad Gates will soon stand anew as tangible symbols of the region’s long history and of its archaeological renaissance. For the people of northern Iraq, it is a welcome sight. “These huge monuments and stretches of city walls became part of the urban landscape, and Mosulites are very attached to them,” says Marchetti. “People in Mosul can now see that we are there to help take care of their heritage.”

Fall of Nineveh in the Bible

Gerald A. Larue wrote in “Old Testament Life and Literature”: “The reaction of at least one individual to the fall of Nineveh is preserved in a poem echoing sheer mocking joy in the defeat of Assyria. The book of the prophet Nahum falls into two parts: Chapter 1 contains an incomplete poem in an alphabetic acrostic form,1 and Chapters 2 and 3 are concerned with Nineveh. Attempts have been made to read out of this short poem something of the writer's status and personality, but there is really no way of learning much about the man for, in his jubilant mood, he treats only one theme-Nineveh. His words form a triumphant shout of praise to Yahweh that the enemy has fallen. His native village of Elkosh (1:1) has not been located.2 The prophet may have been a Judaean who reacted with intense pleasure at the news of Nineveh's defeat or he may have been a descendant of the exiles of Israel living in a village near enough to Nineveh to enable him to witness the siege, thus accounting for the graphic descriptions in his poem. He may have been a cult prophet in Jerusalem. [Source: Gerald A. Larue, “Old Testament Life and Literature,” 1968, infidels.org]

“The two chapters dealing with the siege (chs. 2-3) appear to have been written near the time of the battle. The reference to the sack of Thebes (3:8) guarantees a date after 663, the date of Ashurbanipal's successful attack. The context of the poem suggests a date close to 612. The opening chapter is a separate work which employs theophanic imagery (1:3b-5) and depicts Yahweh as an avenger (1:2-3, 9-11), a wrathful deity (1:6), a refuge for his people (1:7-8), and a deliverer (1:12-13). While it cannot be determined for certain, it seems that someone other than Nahum wrote this chapter. The liturgical or hymnic quality of this section has led to the suggestion that the first chapter was combined with the last two to form a liturgy for use in the New Year festival in the autumn of 612 after the fall of Nineveh.

“The last chapters employ forceful, descriptive terminology to create a compact, vivid word picture of the confusion and horror during the Babylonian attack. In Nahum's thought, God acts against an enemy who has earned punishment and wrath. The closing, mocking verses, indicate that the battle was over and the quietness of death and desolation had descended upon the city and its leaders. All who suffered the cruelty of Assyrian tyranny clap their hands in rejoicing (3:18-19).

“It has also been proposed that the book was developed to propagandize, to encourage a strong stand against Assyria and to extend hopes for the restoration of the nation of Judah.4 It seems better and simpler to recognize the book of Nahum as consisting of genuine oracles by the prophet concerning the fall of Nineveh, to which an introductory poem was added to adapt the total work to liturgical usage.

Herodotus on the Battle Between Persians and Assyrians

Herodotus wrote in 430 B.C.:“The expedition of Cyrus was undertaken against the son of this princess, who bore the same name as his father Labynetus, and was king of the Assyrians. The Great King, when he goes to the wars, is always supplied with provisions carefully prepared at home, and with cattle of his own. Water too from the river Choaspes, which flows by Susa, is taken with him for his drink, as that is the only water which the kings of Persia taste. Wherever he travels, he is attended by a number of four-wheeled cars drawn by mules, in which the Choaspes water, ready boiled for use, and stored in flagons of silver, is moved with him from place to place.I.189: Cyrus on his way to Babylon came to the banks of the Gyndes, a stream which, rising in the Matienian mountains, runs through the country of the Dardanians, and empties itself into the river Tigris. The Tigris, after receiving the Gyndes, flows on by the city of Opis, and discharges its waters into the Erythraean sea. [Source: Herodotus, “The History”, translated by George Rawlinson, (New York: Dutton & Co., 1862]

Fall of Ninevah

“When Cyrus reached this stream, which could only be passed in boats, one of the sacred white horses accompanying his march, full of spirit and high mettle, walked into the water, and tried to cross by himself; but the current seized him, swept him along with it, and drowned him in its depths. Cyrus, enraged at the insolence of the river, threatened so to break its strength that in future even women should cross it easily without wetting their knees. Accordingly he put off for a time his attack on Babylon, and, dividing his army into two parts, he marked out by ropes one hundred and eighty trenches on each side of the Gyndes, leading off from it in all directions, and setting his army to dig, some on one side of the river, some on the other, he accomplished his threat by the aid of so great a number of hands, but not without losing thereby the whole summer season. I.190: Having, however, thus wreaked his vengeance on the Gyndes, by dispersing it through three hundred and sixty channels, Cyrus, with the first approach of the ensuing spring, marched forward against Babylon.

“The Babylonians, encamped without their walls, awaited his coming. A battle was fought at a short distance from the city, in which the Babylonians were defeated by the Persian king, whereupon they withdrew within their defenses. Here they shut themselves up, and made light of his siege, having laid in a store of provisions for many years in preparation against this attack; for when they saw Cyrus conquering nation after nation, they were convinced that he would never stop, and that their turn would come at last. I.191: Cyrus was now reduced to great perplexity, as time went on and he made no progress against the place. In this distress either some one made the suggestion to him, or he thought to himself of a plan, which he proceeded to put in execution. He placed a portion of his army at the point where the river enters the city, and another body at the back of the place where it issues forth, with orders to march into the town by the bed of the stream, as soon as the water became shallow enough: he then himself drew off with the unwarlike portion of his host, and made for the place where Nitocris dug the basin for the river, where he did exactly what she had done formerly: he turned the Euphrates by a canal into the basin, which was then a marsh, on which the river sank to such an extent that the natural bed of the stream became fordable.

“Hereupon the Persians who had been left for the purpose at Babylon by the, river-side, entered the stream, which had now sunk so as to reach about midway up a man's thigh, and thus got into the town. Had the Babylonians been apprised of what Cyrus was about, or had they noticed their danger, they would never have allowed the Persians to enter the city, but would have destroyed them utterly; for they would have made fast all the street-gates which gave upon the river, and mounting upon the walls along both sides of the stream, would so have caught the enemy, as it were, in a trap. But, as it was, the Persians came upon them by surprise and so took the city. Owing to the vast size of the place, the inhabitants of the central parts (as the residents at Babylon declare) long after the outer portions of the town were taken, knew nothing of what had chanced, but as they were engaged in a festival, continued dancing and reveling until they learnt the capture but too certainly. Such, then, were the circumstances of the first taking of Babylon. I.192:

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024