Home | Category: Arabs and Arabic

ARAB SOCIETY

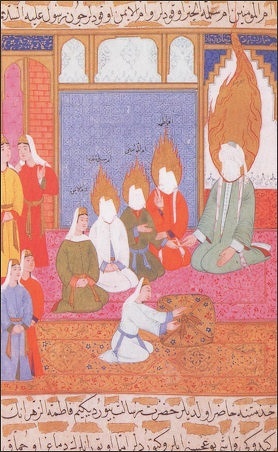

Muhammad with his family anf forth wide Aisha

The Arab world has been dominated by a tradition-bound patriarchal society in which wealth has been controlled by men, property was passed down to male children, women were subordinate to men. Women gained power as the got older as the mother of male children or senior wives.

The Arab world has traditionally been a male-dominated society where bonds were made through clans, tribes and villages.. Bedouin traditions of hierarchy persist in modern society. It is evident at sporting evident where princes and sheiks and VIPs sit in front and regular people sit in the stands.

Honor is an important concept in the Arab and Muslim world. Honor has traditionally been a male thing that came from defending one’s property, family, clan and tribe. Particular attention has been placed on protecting the women in a family—mothers, sisters, wives and daughters. Women were expected to be pure and modest so as not arouse other males and disrupt the harmony of the society and bring shame to the dominate male.

Some have argued that there never was a period of theological and political development in the Arab world comparable to the Renaissance or the Age of Enlightenment.

Arabs: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Who Is an Arab? africa.upenn.edu ; Encyclopædia Britannica article britannica.com ; Arab Cultural Awareness fas.org/irp/agency/army ; Arab Cultural Center arabculturalcenter.org ; 'Face' Among the Arabs, CIA cia.gov/library/center-for-the-study-of-intelligence ; Arab American Institute aaiusa.org/arts-and-culture ;

Websites and Resources: Islam Islam.com islam.com ; Islamic City islamicity.com ; Islam 101 islam101.net ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Religious Tolerance religioustolerance.org/islam ; BBC article bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/islam ; Patheos Library – Islam patheos.com/Library/Islam ; University of Southern California Compendium of Muslim Texts web.archive.org ; Encyclopædia Britannica article on Islam britannica.com ; Islam at Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Islam from UCB Libraries GovPubs web.archive.org ; Muslims: PBS Frontline documentary pbs.org frontline ; Discover Islam dislam.org

Traditional Rural Arab Village Society

In village and pastoral societies, extended families have traditionally lived together in tents (if they were nomads) or homes made from stone or mud brick, or whatever other materials were available. Men were mainly responsible for tending the animals while women took care of the fields, reared the children, cooked and cleaned, managed the household, baked bread, milked goats, made yogurt and cheese, gathered dung and straw for fuel, and made sauces and preserves with grapes and figs.

Village society has traditionally been organized around the sharing of land, labor and water. Water was traditionally divided by giving landowners a certain share of water from a canal or redistributing plots of land. Crop yields and harvest were distributed in some way based on ownership, labor and investment.

Describing the Arab tribal mentality the Iraqi editor Saad al Bazzaz told the Atlantic Monthly: “In the villages, each family has its own house, and each house is sometimes several miles from the next one. They are self-contained. They grow their own food and make their own clothes. Those who grow up in the villages are frightened of everything. There is no real law enforcement or civil society, Each family is frightened of each other, and all of them are frightened of outsiders...The only loyalty they know is to their own family, or to their own village.”

Roads have decreased isolation and increased contacts with outsiders. Radios, television, the Interent and smart phones bring new ideas and exposure to the outside world. In some places, land reform has brought a new system of landowning, agricultural credit and new farming technology. Overcrowding and lack of opportunities has prompted many villagers to migrate to the cities and towns.

Bedouin Society

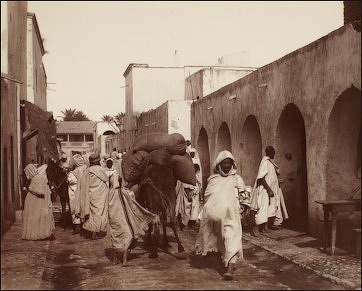

19th century Arabs in Aleppo

Bedouins are Arabs and desert nomads who hail from and continue to live primarily in the Arabian peninsula and the Middle East and North Africa.As is true with all Arabs, Bedouins live in patrilineal societies. Most are members of large patrilineal descent groups, which are linked by agnation to larger lineage groups, tribes and even confederations of tribes. “Bedouins frequently name more than five generations of patrilineal ancestors and conceptualize relations among descent groups in terms of a segmentary genealogical model, with each group nested in a larger patrilineal group. Within this structure is a framework for forging marriage alliances, and settling disputes and administering justice.

Bedouins are fiercely loyal to clan and tribe and their society is organized around a series of real and fictional kin groups. The smallest household units are called bayt (plural buyuut). They in turn are organized into groups called fakhadhs , which in turn are united into tribes. Large tribes are sometimes divided into subtribes. The leaders of buyuut and fakhadhs are often organized into a Council of Elders, often directed by tribal leader or sheik.

Bedouins have traditionally been organized into “nations," or tribal groups of families united by common ancestor and shared territorial claims. These nations are led by leaders selected according to a universal selection process and operating in an environment that was constantly changing ecologically and politically. Only in the 20th century has their system been undermined by more powerful authoritarianism namely national governments.

Social control is exercised through honor and shame which not only defines an individual but also defines his family and even clan. Honor is inherited and has to asserted from time to time to remain relevant. The honor of a man is defined by his individual behavior and those of his male kin. Female honor is something that male relatives are responsible for upholding. It is often defined in terms of chastity and is regarded as something that can not be regained after it has been lost. It is considered a serious, shameful matter if female honor is taken or somehow compromised. Serious breaches of honor can result in execution of expulsion from the tribe.

Family in the Arab-Muslim World

Islam defines individual rights for husbands and wives with their family. Men are literally head of the households and responsible to the welfare of their wife (or wives) and children. Women usually oversee the family finances and the raising of children. A wife has the right to any property she possess (including her dowry) and is not required to tell her husband how much she has or contribute any of it to family expenses. Women however are obliged to follow their husband’s commands in both private and public matters.

Bedouins and villagers have traditionally found security among family members in times of hardship and in old age. According to the Encyclopedia of World Cultures: “A mother is viewed as a symbol of warmth and love throughout a child’s life. A father is viewed as a stern disciplinarian who administers corporal punishment and instills a degree of fear within his children.” Parents have enough influence to prohibit friendships they disapprove of.

The Arab world has been dominated by a tradition-bound patriarchal society in which wealth has been controlled by men, property was passed down to male children, women were subordinate to men. Women gained power as the got older as the mother of male children or senior wives. The patrilineal system is reflected in Islamic rules of inheritance, which give more to boys than girls, especially in terms of real estate.

Qur’an, Family and Inheritance

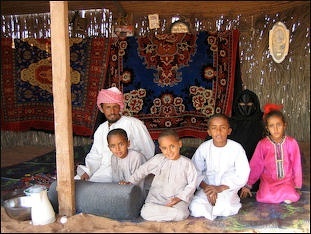

Bedouin family

Laws defining the economic independence of women and the responsibility of men members are not explicitly laid out in the Qur’an but rather are based on the right of a man to marry more than one wife and the right to divorce his wife by repudiation.

The Qur’an is very specific when it comes to defining inheritance rules but the system is complex and took Muslim lawyers centuries to unravel and implement. Today there are Muslim lawyers that specialize in inheritance.

In most cases inheritance is equally divided among sons and daughters with daughters receiving half the share of sons after “obligatory quotas” are given to father, mother and wife and wives and debts are paid off. If there are no sons then son’s son, brothers are next in line. Daughters son’s are excluded by Sunnis but accepted by Shia.

Muslims may not inherit from Jews and Christians and visa versa. There also rules that prevent spendthrifts from getting too large a share and that prevent the alienation by will of more than a third of an individual’s property. The are also detailed laws on endowments

Men and Women in the Arab-Muslim World

Men have traditionally had their friends and women had their friends. According to the Encyclopedia of World Cultures: “The lives of Arab village men and women are very distinct. Men work in the fields. women in the home. For social contact men go to coffee houses, but women visit neighbors or relatives or receive such visits in their own homes. Men and women often eat separately and always pray separately.”

Arab-Muslim society is a male-dominated society. Most of the people you see on the streets are men. Men are revered and seen as their heirs of family titles, property and legacies. They like to gather in teahouses and drink tea, smoke, char, play card and board games and watch the news or soccer games on small televison elevated in the a corner. Some men constantly finger their worry beads. Sheik is the name given to a tribal leader or man admired for his piety.

Among men, size matters. Tall large men and men with large hands or penises tend to be admired. Young Arab men reportedly can not tolerate insults to their manhood. It has been said, "A man's virility is often measured by ability to protect his women's virtue."

Society in the Early Islamic Period

"Prophet Arrives in Medina"

Arthur Goldschmidt, Jr. Wrote in “A Concise History of the Middle East”: “In the early period, the social structure of Islam was far more formalized than that of our society nowadays. Every class had certain rights and duties, as did each religion, sex, and age group. The rulers were expected to preserve order and promote justice among their subjects, to defend the ummah against non-Muslim powers, and to assure maximum production and exploitation of the wealth of their realm. Sunni Islam developed an elaborate political theory. It stated that the legitimate head of state was the caliph, who must be an adult male, sound in mind, descended from the Quraysh tribe. His appointment must be publicly approved by other Muslims. In practice, though, the assent given to a man's becoming caliph might be no more than his own. Some of the caliphs were juveniles. A few were insane. Eventually, the caliphal powers were taken over by vizirs, provincial governors, and military adventurers. The fiction, however, was maintained, and the Sunni legist might have asked whether to be governed by a usurper or a despot was worse than by no ruler at all. The common saying was that a thousand years of tyranny was preferable to one day of anarchy. [Source: Arthur Goldschmidt, Jr., “A Concise History of the Middle East,” Chapter. 8: Islamic Civilization, 1979, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu /~]

“The abuse of political power was often checked by the moral authority of the ulama. The rulers were to govern with the aid of classes commonly called the "men of the pen" and the "men of the sword." The men of the pen were the administrators who collected and disbursed the state revenues and carried out the rulers' orders, plus the ulama who provided justice, education, and various welfare services to Muslims. The Christian clergy and the Jewish rabbinate had functions in their religious communities similar to those of the ulama. The men of the sword expanded and defended the borders of Islam and also, especially after the ninth century, administered land grants and maintained local order. /~\

Social Groupings in Early Islamic Society

Arthur Goldschmidt, Jr. Wrote in “A Concise History of the Middle East”: “The great majority of the people in the Muslim world belonged to the subject class, responsible for producing the wealth of the ummah. The most basic division of subjects was between nomads and settled peoples, with the former group further divided into countless tribes and clans, and the latter broken down into many occupational groups. Urban merchants and artisans had various trade guilds, often tied to specific religious sects or Sufi orders (brotherhoods of Muslim mystics), which looked out for their common interests. By far the largest group was the peasant population, whose status tended to be lower. There were also slaves; some served in the army or the bureaucracy, others worked for merchants or manufacturers, and still others were household servants. Plantations using slave labor were rare. Islam did not prohibit slavery, which was common in seventh-century Arabia, but it enjoined masters to treat their slaves kindly and encouraged their liberation. Slaves could be prisoners of war, children who had been sold by their parents, or captives taken by slave traders from their homes. [Source: Arthur Goldschmidt, Jr., “A Concise History of the Middle East,” Chapter. 8: Islamic Civilization, 1979, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu /~]

Umar (the second Caliph) and the poor widow

“Crossing these horizontal social divisions were vertical ones based on ancestry, race, religion, and sex. Although various hadiths showed that Muhammad and his companions wanted to play down distinctions based on family origins, early Islam did nonetheless give higher status to descendants of the earliest Muslims or of Arabs generally than to later converts to the religion. As you have seen in earlier chapters, Persians and then Turks gradually rose to the same status as Arabs. Other ethnic groups, such as Berbers, Indians, and Black Africans, kept a distinct identity and often a lower status even after their conversion to Islam. Racial discrimina- tion, however, was generally less acute than it has been in Christian countries in modern times. /~\

“The divisions based on religion, though, were deep and fundamental. Religion was a corporate experience, a community of believers bound together by adherence to a common set of laws and beliefs, rather than a private and personal relationship between each person and his maker. Religion and politics were inextricably intertwined. Christians and Jews did not have the same rights and obligations as Muslims; they were protected communities living within the realm of Islam where the Shari'ah prevailed. Exempted from military duties, Christians and Jews were also not allowed to bear arms. If they did not have to pay zakat, they did have to pay a head tax vfizyah) plus whatever levies were needed to maintain their own religious institutions. They could not testify in a Muslim court against a Muslim, or ring bells or blow shofars ("ram's horns") or have noisy processions that might interrupt Muslim worship. Sometimes the restrictions were more humiliating, and in a few cases their lives and property were threatened. But they were able to maintain their identity as Jews or Christians and follow their own laws and religious beliefs for hundreds of years. The treatment of religious minorities in Muslim countries that upheld the Shari'ah was better than in those that have recently watered the code down or abandoned it altogether, and much, much better than the treatment of Jews in medieval Christendom, tsarist Russia, or Nazi Germany. /~\

“As for social divisions based on sex, Islam (like most religions that grew up in the agrarian age) is patriarchal and gives certain rights and responsibilities to men that it denies to women. Muslims believe that biology has dictated different roles for the two sexes. Men are expected to govern countries, wage war, and support their families; women to bear and rear children, take care of their households, and obey their husbands. There is little women's history in early Islam; a few women took part in wars and governments, wrote poetry, or had profound mystical experiences, but most played second fiddle to their husbands, fathers, brothers, or sons. /~\

Islam and Society

The Qur’an and sharia describe what is expected from families and marriages thus these institutions are remarkably similar whether they be in Kuwait, Indonesia or the Sudan and tend to stay within certain limits even when local and ethnic customs are taken into consideration.

Islamic concepts about society and family were shaped by the nature of Arab society in Muhammad’s time. Then, society was organized around kin-groups that shared property held in common under a senior patriarch. Islam was offered as a kind of alternative to the tribal system but many of its principals which held the Muslim community together were tribal in nature: namely that clans imposed certain obligations among its members.

Muslim law is formulated to deal with the competing claims of family-groups and kin-groups (clans and tribes), and tending to favor the kin group. A wife, for example, according to some interpretations, is regarded as the possession of her father not her husband even after she is married.

Families, Clans and Status in the Arab World

Algeria in 1889

Traditional society revolves around extended families. Status is based on family background, social class and education. Making a person an honorable kin is the one of the highest honors an Arab can give someone.

Loyalty is very important among Arabs and is clearly ranked. An individual’s first loyalty is to his 1) immediate family and 2) extended family, followed by 3) friends within a clan or tribe, then 4) clan or tribe, 5) Muslim sect, 6) Arab Muslims, 7) country and 8) non-Arab Muslims. It is unusual for a community of different tribes to come together to do something for he common good of a town.

“ Rabaa” is a local Arabic word for clan. They are usually defined a group that has a common ancestor that can be traced back five or six generations or more. Cities, towns and communities have traditionally been dominated by powerful families and clans.

Tribalism and Tribes in the Middle East

Tribalism is very big in the Middle East. Millions of people belong to major tribes, which break down into smaller clans. The largest tribes have more than 1 million members; the smaller ones, only a few thousand. Some have been around for centuries, are comprised of Arabs and non-Arabs and have related branches in different countries in the Middle East.

Tribes tend be defined as group with a specific name. Sometimes they are made up of the inhabitants of villages in a specific area. Other times they are more dispersed. Often times they claim a common ancestor but often the links to this ancestor are unknown and perhaps fictitious. Sometimes the composition of a tribe changes to accommodate new alliances and the break up of old ones

The leaders of tribes are called sheiks. They are usually selected by elders in the tribe. With tribes associated with a specific area, sometimes they have been in that area for a long time. Other times they attain it through military incursion or a government connection. Tribes often have a strict caste-like hierarchy and codes of conduct and justice that have allowed them endure through the centuries.

Bedouin Tribes and Sheiks

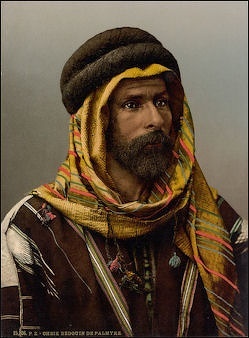

Bedouin chief of Palmyra

Most Bedouins belong to small tribes that traditionally lived together in tent camps in the desert. The Al Sawaada tribe, a typical tribe, had 400 members. The largest tribes have 3,000 tents and 75,000 camels. Large tribes are hardly ever together. There simply is not food in a given place in the desert to support them all. Groups that move through the desert usually have 20 to 70 members. ☼

Each Bedouin tribe member wears slightly clothes to indicate locality, social position and marital status, with these things usually being indicated by embroidery on their cloak, headdresses, jewelry and hairstyle worn on special occasions.

Different tribes have different reputations. The Beni Skar Bedouins have a reputation for being particularly fierce. The Duru, the Harasi, the Yal Wahiba are tough Bedouin tribes that live in southern Oman. Residing near their gravel flats of the Empty Quarter, they survive by finding meager feed for their camels and wander from one bitter water hole t another.

Entire tribes are held responsible for a murder or another crime committed by one member of the tribe. In the case of a murder a tribe must wander endlessly to keep one step ahead of the their pursuer until blood money can be raised.

A sheik is the head of a tribe. He is often the wealthiest member of the tribe and may posses more than a thousand camels. Among the important criteria in choosing a leader are age, religious piety, personal qualities, generosity and hospitality.

Sheik generally wield their authority through a chain of command through subtribes, fakhadhs, and buyuut. They have traditionally been in charge of distributing grazing rights and settling disputes. A sheik often has no muscle to back him up and wields power through moral authority and judging the desires of tribe members.

Tribal Mentality and Values in the Middle East

Describing the Arab tribal mentality the Iraqi editor Saad al Bazzaz told the Atlantic Monthly: “In the villages, each family has its own house, and each house is sometimes several miles from the next one. They are self-contained. They grow their own food and make their own clothes. Those who grow up in the villages are frightened of everything. There is no real law enforcement or civil society, Each family is frightened of each other, and all of them are frightened of outsiders...The only loyalty they know is to their own family, or to their own village.”

“Each of the families is ruled by a patriarch, and the village is ruled by the strongest of them. This loyalty to the tribe comes before everything. There are no values beyond power. You can lie, cheat, steal, even kill, and its okay so long as you are a loyal son of the village or the tribe. Politics...is a bloody game, and its all about getting or holding power.”

Tribal values are held in high regard. Family and tribe are the only people who can be trusted. If there is a threat from the outside the tribe is expected to come together to fight it. Tribal alliances are based on strength. Any perceived weakness can lead to a tribes’s demise.

Many still adhere to the old tribal rules and customs and do what their sheiks tell them. Members are often linked together by a code of honor that is not all that different than the one followed by Mafia dons in Sicily and the Godfather films. Individual members are expected to help each other in a time of need

Certain tribes and clans are known for having certain qualities such as cleverness, resourcefulness and cleverness. Women are regarded as possessions of the tribe. If they go to another tribe without some sort of compensation it is regarded as a kind of betrayal

Tribal Leaders and Politics

Tribes are usually led by chiefs or a council of elders. Their primary goal is to maintain and expand the power of the tribe or village. They also preserve the collected memory of the tribe, address concerns the affect the entire tribe or specific members, mediate disputes and settle matters that threaten to break up the tribe. Many villages also have an old spiritual leader who is regarded as the keeper of the Qur’an.

Sheik is often the name given to a tribal leader. It means teacher or a man admired for his piety. They are usually hereditary rulers or members of a dominate family. Sometimes they are selected on merit, military strength, religious piety or skill settling disputes and dealing with other tribes and the government. Other times they take power using their political skill. Some are preachers. Sometimes they wear cloaks edged with gold or something else to identify them.

The leaders of traditionally pastoral groups generally have little power other than that given to them by members of their group. Those in settled area often wield more power often because they have more people.

Tribes, Politics and the Modern World

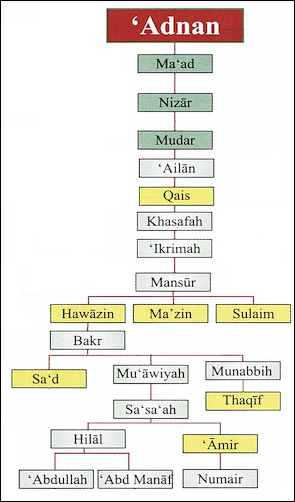

geneology of the Banu Hawazin tribe

Tribes have been major players in the brutal politics of the Middle East. The tribes have a reputation for being heavily armed, very devout and nationalistic. They have played a role in controlling territory under the Ottomans and colonial leaders.

Often a few dozen of the larger tribes are credited with playing a major role in controlling a Middle Eastern country. When certain tribes have political power they tend to hand out jobs and patronage to family or tribe members. Middle Eastern tribes have been involved in countless wars, battles and skirmishes and are known for switching sides in the middle of a battle.

Tribalism has traditionally been strongest in the countryside but as the Middle East has become more urbanized tribalism has moved into the cities. The old tribes transplanted their power to the cities and new tribes grew out of labor unions, professional organizations, universities and other social organizations which operate like tribes.

Tribalism Versus Education in Yemen

At the heart of Yemen's poverty, malnutrition and religious extremism is a tribal culture that prevails over schooling. Educators persevere despite a lack of materials, adequate pay and respect. "Students are learning, but their minds don't change," Salah Rashed Alhanshali, a former public school principal told the Los Angeles Times. "They graduate with a little knowledge, but they don't aspire to be scientists. They yearn to be tribal sheiks. It's the stigma of our history. Teachers are belittled and scrimp by, and students who want to succeed are discouraged by nepotism and corruption." The tribal culture "prevails over education," says Ayub Nagi Barea, a geography teacher."These kids see that the tribal life gives rewards. 'A mathematics teacher,' says the tribe, 'what is this?' " [Source: Jeffrey Fleishman, Los Angeles Times, December 24, 2009 ^]

Jeffrey Fleishman wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “In the Arab world's poorest country, where there's civil war in the north and a secessionist movement in the south, the tribe offers security and respectability. Images of clan leaders are emblazoned on SUVs that whisk through neighborhoods and villages like armed entourages. Even Kumaim, deputy principal for 15 years, had to tend to tribal affairs when his father was ill and he took over as a sheik. He and his two wives have given the tribe 10 children who, he noted without a trace of irony, are enrolled in private, not public, schools. ^

“But it is more than the allure of the tribe that worries the teachers. The men, dressed in tunics and blazers, sat in the courtyard listing problems until dusk, when they broke talk on the fate of Yemen's education system to answer the call to prayer. They all moonlight, mostly as teachers and principals in other schools, and one of them said: "Islam tells us to teach. If the pay is not enough, there is spiritual reward from God."” ^

Urban Mentality in the Tribal Arab World

In the Arab and Muslim world, as there are everywhere, there are major differences between the people of the cities and the people of the countryside. Describing the mentality of urban Arabs Saad al Bazzaz told the Atlantic Monthly: “In the city the old tribal ties are left behind. Everyone lives close together. The state is part of everyone’s life. They work at jobs and buy their food and clothing at markets and in stores. There are laws, police, courts, and schools. People in the city lose heir fear of outsiders, and take an interest in foreign things. Life in the city depends on cooperation, in sophisticated social networks.

“Mutual self-interest defines public policy. You can’t get anything done without cooperating with others, so politics in the city becomes the art of compromise and partnership. The highest goal of politics becomes cooperation, community, and keeping peace. By definition, politics in the city becomes nonviolent. The backbone of urban politics isn’t blood, it’s law.”

On some places, while Western-influenced elite become richer and more secularized, the poor, embracing more conservative values, become more reactionary and hostile. The material and cultural gap lays the foundation for jihadism.

Revenge, Vendettas and Blood Feuds

Strength is greatly admired. To give in or compromise is often seen as an indication of weakness. Revenge is viewed as strength and defended as just. Revenge is often based on defending honor and Betrayal is one of the worst sins. The Princeton professor Bernard Lewis has argued that Islamic nations have never been receptive to Western idealism but they fear and respect force. Some critics of Islam have argued that Christianity emphasizes forgiveness and peace while Islam talks about jihad and violence.

Vendettas, honor killings and revenge killings and blood feuds are a tradition among at least some Bedouin and Arab tribes. These traditions have been around since ancient times. They are deeply rooted elements of the rural Arab honor code and are believed to have been essential to maintaining some kind of peace in an unforgiving place like the desert. Vendetta values are alive in the Arab world. One Israeli expert on Iraq told Newsweek. “The traditional tribal values of the Middle East despise somebody who does not avenge the blood of his kin.”

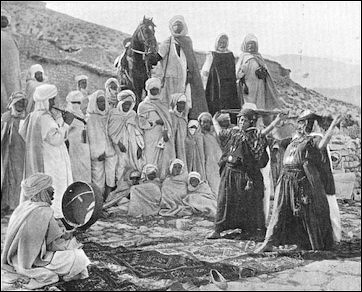

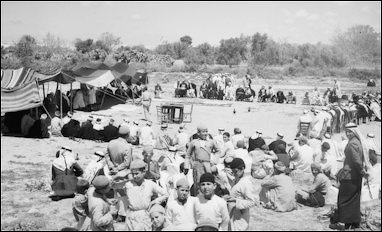

End of a blood feud at el Hamani village near Mejdal, Israel in 1943

The Qur’an says: "Prescribed for you is retaliation” This is taken to mean that revenge is allowed as long as it is within prescribed limits. The Qur’an states that a slain person has the right to avenge the killing but adds mercy is preferable. The Hanfai school alone defined the principle of a life for a life (except for a slave or son) while the other schools recognized degrees of justifiable revenge based on status, and said that revenge can not be used for the death of a non-Muslim or slave.

In some rural areas of Egypt many people carry unlicensed firearms and revenge killings and vendettas occur. Revenge, blood feuds and blood money are deeply rooted elements of the rural Egyptian honor code. In the early 2000s, a farmer was shot 30 times in the head in a revenge attack by his cousins in a dipute that began when a man was killed in arguments over the building of some steps. The attack was carried out with automatic rifles the attackers bought with blood money paid by the victim’s family.

Blood Money

Within Islamic law, revenges for an accidental death are not justified, but the payment of blood money is allowable. There is some disagreement among legal schools as to whether a party might accept blood money for a deliberate murder.

Payment for blood money has traditionally been paid by the slayers extended family of clan or tribe The traditional payment for a free Muslim was 100 camels or 1,000 sheep, with less for a non-Muslim or slave and amounts varying in accordance to status. Similar principals apply to mutulations minor injuries and are the basis for sharia laws for murder and theft.

Respected elders are used as go-between to settle the disputes. Blood money amounts are usually decided by village elders.

Bedouin Conflicts, Raids and Revenge Killings

Bedouins have traditionally gone out on ghazwas ("raids") to settle scores and rustle livestock. An early Arabic poem goes: "With the sword I will wash my shame away," Let God's doom bring on me what it may!" In the old days, tribal conflicts often revolved around the rights to water and pastures. Brutal battles and the loss of many lives was often the result of such conflicts. Modern laws and law enforcement officers have largely been able exert control over Bedouins and pacify them.

Bedouins have nasty blood feuds that sometimes end in murder. Describing a revenge killing in southern Arabia in 1946, Wilfred Thesiger wrote: "Bin Mautlauq spoke of the raid in which young Sahail was killed. He and fourteen companions had surprised a small herd of Saar camels. The herdsmen had fired two shots at them before escaping, on the fastest of his camels, and one of these shots hit Sihail in the chest. Bakhit held his dying son in his arms as they rode across the plain with the seven captured camels. It was late in the morning when Sahail was wounded, and he lived till nearly sunset, begging for water which they had no t got." " [Source: Eyewitness to History , edited by John Carey, Avon, 1987]

"They rode all night to a small Saar encampment under a tree in a shallow valley. A woman was churning butter in a skin, and a boy and girl were milking the goats. Some small children sat under a tree. The boy saw them first and tried to escape but they corned him against a low cliff. He was about fourteen years old, a little younger than Sahail, and unarmed. When they surrounded him he put his thumbs in his mouth as a sign of surrender, and asked for mercy. No one answered him."

Bedouin raid

Bakhit slipped own off his camel, drew his dagger, and drove it into the boy's ribs. The boy collapsed at his feet, moaning, 'Oh, my father! Oh, my father!' and Bakhit stood over him till he died. He then climbed back into his saddle, his grief a little soothed by the murder...The small, long-haired figure, in white loincloth, crumpled on the ground, the spreading pool of blood, the avid clustering flies, the frantic wailing of the dark-clad women, the terrified children, the shrill incessant screaming of a small baby."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994). “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, BBC, Al Jazeera, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018