Home | Category: Islam and the Qur’an / Mosques, Mecca and Muslim Holy Places / Muslim Education, Government and Finance

ISLAMIC STRUCTURE AND ORGANIZATION

Inside a Tunisian madrassah Islam is a heterogeneous religion that recognizes no authoritative source of doctrinal interpretation like the Pope. The lack authoritative source of doctrinal interpretation means that Islam lacks a hierarchal structure like the Catholic church and anyone can interpret the Qur’an and other religious scriptures anyway they like. This makes Islam more egalitarian and democratic in some ways but also makes it easier for Muslim extremists to gain influence and promulgate their views.

Muslims believe in direct communion with God and technically human intermediaries are not necessary for followers to have a relationship God. Even Muhammad was only a messenger. Consequently there are no priests, popes, holymen or saints in Islam. Every Muslim has equal access to God and any Muslim of good character can be the leader of prayers at a mosque.

Islam has no sacramental system, and almost no liturgy. There is no “clergy” in the Christian sense. There is no concept of a “church.” Islam has “rigorously excluded from its religious leadership any of the spiritual functions and prerogatives of a priesthood.” The basis of some of Islam's structures is rooted in Bedouin traditions of blood kinship, egalitarianism and surrendering to strong authority (Allah in the case of Islam).

Websites and Resources: Islam IslamOnline islamonline.net ; Institute for Social Policy and Understanding ispu.org; Islam.com islam.com ; Islamic City islamicity.com ; BBC article bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/islam ; University of Southern California Compendium of Muslim Texts web.archive.org ; Encyclopædia Britannica article on Islam britannica.com ; Islam at Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Muslims: PBS Frontline documentary pbs.org frontline

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Ulama in Contemporary Islam: Custodians of Change” by Muhammad Qasim Zaman Amazon.com ;

“What Is Religious Authority?: Cultivating Islamic Communities in Indonesia” by Ismail Fajrie Alatas Amazon.com ;

“Sharī'a: Theory, Practice, Transformations” by Wael B. Hallaq Amazon.com ;

“Introduction to Islamic Law: Principles of Civil, Criminal, and International Law under the Shari‘a” by Jonathan G. Burns Amazon.com ;

“Sharia Incorporated: A Comparative Overview of the Legal Systems of Twelve Muslim Countries in Past and Present” by Isabell Otto Amazon.com ;

“Fatwa and the Making and Renewal of Islamic Law: From the Classical Period to the Present”by Omer Awass Amazon.com ;

“The Four Juristic Schools: Their Founders, Development, Methodology & Legacy”

by Islamic Research Team Do Fatwa Kuwait Amazon.com

Simplicity if Islamic Worship and Organization

One of Islam’s attractions is its simplicity. Seyyed Hossein Nasr wrote in the “Science and Civilization in Islam: “The creed of Islam "there is no divinity other than God and Muhammad is his prophet" summarizes in its simplicity the basic attitude and spirit of Islam. To grasp the essence of Islam, it is enough to recognize that God is one, and that the Prophet, who is the vehicle of revelation and the symbol of all creation, was sent by him. This simplicity of the Islamic revelation further implies a type of religious structure different in many ways from that of Christianity. There is no priesthood as such in Islam. Each Muslim being a "priest" is himself capable of fulfilling all the religious functions of his family and, if necessary, of his community; and the role of the imam, as understood in either Sunni or Shia Islam, does not in any way diminish the sacerdotal function of each believer. [Source: Seyyed Hossein Nasr, “Science and Civilization in Islam,” New American Library. NY 1968]

The local Islamic community is supposed to be "a single hand, like a compact wall whose bricks support each other." Leaders in Muslim societies have traditionally greeted all comers in a pavilion to read petitions, hear grievances and mete out justice.

Shiite Islam is regarded as more organized and hierarchal than Sunni Islam. Vali Nasr, author of the “The Shia Revival”, compares Shiites to Catholics because of their emphasis on religious hierarchy, mysticism, worship of a holy family (the Prophet’s descendants) and clerical intercession while the Sunnis are like Protestants with their lack of a unified clerical establishment and reliance on original texts, namely the Qur’an and the Sunnah, as the sect’s authority of religious questions.

Islamic Communities

Indonesian imam conducting a marriage ceremony An Islamic community is known as as an “umma” (also spelled ummah. It can be a local or transnational group of followers of Islam More like clubs than organized churches,local ones are involved in a number of community and charity activities and is "entrusted with the furtherance of Good and repression of Evil." Only Muslims are allowed to be members of the Muslim community. Members are called “mukallag” which means “one who is required to fulfill his religious duties and observances in accordance with sharia.”

The focus of Islamic community life is the mosque, where people gather for prayer, reflection and social activity. Adult Muslim men are expected to attend a Friday sermon called the Salat ul-Jumuʾah, or "prayer of gathering." Women are encouraged to attend, but those with domestic responsibilities are allowed to pray at home. Many mosques function as community centers, where meetings are held and offer various services to the poor and instruction for children.[Source: Encyclopedia.com]

According to the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”: The Sufi orders, or brotherhoods of Islamic mystics, also developed an institutional structure and organization of disciples, followers, and helpers led by the master (pir or shaykh), who functions as the spiritual leader and head of the community. Some of the more prominent brotherhoods developed international networks. At times the heads of Sufi brotherhoods also became military leaders. When these religious and social organizations turned militant, as with such eighteenth- and nineteenth-century jihad movements as the Mahdi in the Sudan, the Fulani in Nigeria, and the Sanusi in Libya, they fought colonial powers and created Islamic states. [Source: John L. Esposito “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Muslim Leaders

Although a formal organization of ordained priests has no basis in Islam, a variety of functionaries perform many of the duties conventionally associated with a clergy and serve, in effect, as priests. One group, known collectively as the ulama, has traditionally provided the orthodox leadership of the community. The ulama unofficially interpret and administer religious law. Their authority rests on their knowledge of sharia, the corpus of Islamic jurisprudence that grew up in the centuries following the Prophet's death. [Source: James Heitzman and Robert Worden, Library of Congress, 1989 *]

The members of the ulama include maulvis, imams, and mullahs. The first two titles are accorded to those who have received special training in Islamic theology and law. A maulvi has pursued higher studies in a madrasa, a school of religious education attached to a mosque. Additional study on the graduate level leads to the title maulana.*

Villagers call on the mullah for prayers, advice on points of religious practice, and performance of marriage and funeral ceremonies. More often they come to him for a variety of services far from the purview of orthodox Islam. The mullah may be a source for amulets, talismans, and charms for the remedying of everything from snakebite to sexual impotence. These objects are also purported to provide protection from evil spirits and bring good fortune. Many villagers have implicit faith in such cures for disease and appear to benefit from them. Some mullahs derive a significant portion of their income from sales of such items.*

According to the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”: “In general, Islam does not have an official organizational structure or hierarchy. It technically lacks an ordained clergy, and major religious rituals, such as prayers or marriage ceremonies, do not require a religious official. Over time, however, the early scholars of Islam, the ulama (the learned), became a clerical class, asserting their prerogative as the guardians and official interpreters of Islam and adopting a clerical form of dress. They became the primary scholars of law and theology, teachers in schools and universities or seminaries (madrasahs), judges, muftis, and lawyers, as well as the guardians and distributors of funds from religious endowments that provided support for such institutions as schools, hospitals, and hostels and for the poor. In time, in some Muslim countries, senior religious officials were appointed by governments with titles such as grand mufti. Some forms of Shiism, in particular the Twelvers (Ithna Ashari) of Iran and Iraq, developed a hierarchical system of religious officials and titles. Their senior leaders are called ayatollahs, and at the apex of the system are grand ayatollahs. [Source: John L. Esposito “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Imam

Sheikh Syed Abdul Qadir Jilani An imam is the spiritual head of a Muslim community or simply a prayer leader. Shias (Shiites) also use the term as the title for Muhammad's successors, male descendants through his cousin and son-in-law Ali The imam at a mosque is generally a teacher, a learned person or a prayer leader. Every mosque has an imam and an assistant imam that takes the place of the imam if he is sick or out of town, or steps in if the imam stumbles or forgets a verse.

Imam are important people in both rural and urban society, leading a group of followers. The imam's power is based on his knowledge of the Qur’an and memorization of phrases in Arabic. Relatively few imams understand Arabic in the spoken or written form. An imam's power is based on his ability to persuade groups of men to act in conjunction with Islamic rules. In many villages the imam is believed to have access to the supernatural, with the ability to write charms that protect individuals from evil spirits, imbue liquids with holy healing properties, or ward off or reverse of bad luck. [Source: “Countries and Their Cultures”, The Gale Group Inc., 2001]

Imam have traditionally lead prayers and sometimes made sermons. Leading the mosque in prayers is regarded as a great honor. Some imam are self appointed and have little formal religious training. Some are fundamentalists who bully their way into their positions or draw on the support of Muslim extremists. Often they are consulted on matters for which they receive little training such as arranged marriages and mediating disputes between vendors.

Hazrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad wrote: “There is one leader who leads the congregation in all such prayers. That leader is not an ordained priest; anyone whom the people consider worthy of this task is chosen as the Imam. The assembly is admonished to be arrayed behind the Imam in perfectly straight lines, each worshipper standing close to the other, shoulder to shoulder, with no distance between any two worshippers. They follow the Imam perfectly in everything that he does. As he bows they bow, as he stands they stand. As he prostrates they prostrate. Even if the Imam commits a mistake and does not condone it even after a reminder, all followers must repeat the same. To question the Imam during the prayer is not permitted. All face the same direction without exception, facing the first house of worship ever built for the benefit of mankind. No-one is permitted to reserve any special place behind the Imam. In this regard the rich and poor are treated with absolute equality, so also the old and the young. Whoever reaches the mosque ahead of others has the prior option to sit wherever he pleases. None has the right to remove others from the place that they occupy, except for reasons of security etc., in which case it becomes an administrative measure. Thus the Islamic system of prayer is rich not only in spiritual instruction but also in communal and organisational instruction. [Source: Hazrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad, Khalifatul Masih IV, Ahmadiyya Muslim Community]

Sheikhs, Ulama, Mullahs, Qadis and Muftis

Sheik means teacher. It is the name given to a man admired for his piety. Sheiks are sometimes imam or preachers. They are often also chiefs, village leaders or even the leader of a large tribe or nation. Many villages have an elder spiritual leader who is regarded as the keeper of the Qur’an.

"Mullah" is an honorific word for a learned person who acts a teacher and judge and who expounds Muslim law. He is regarded more like a high-ranking professor of the religion rather than a priest. Mullah is term most often used in Iran and Shiite countries. A person generally needs to finish a Qur’anic school to obtain that title of mullah. Most mullahs live relatively modestly.

“Ulama” refers to a class of mullah or religious scholars that are trained in theology and are respected interpreters of the Qur’an. Influential in conservative and rural communities, many ulama can trace their lineage back to the Prophet or members of his family or his early followers. In the past they often formed the urban elite. They and the children were educated the most prestigious madrasahs (Muslim schools). “Ulama” is the plural of “alim” (“scholar”).

Is South Asia, ulama (religious scholars) provide guidance to the people, but they also offer legal and religious opinions on all matters concerning Muslims, including foreign and domestic policy. In a less formal way there are the pirs (Sufi masters and teachers), who are revered among many Muslims. Pirs provide guidance and offer advice to those who seek it on personal and professional matters. [Source: “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”, Thomson Gale, 2006]

A Muslim judge is known as a qadi (“cadi” ). A mufti is an Islamic legal expert. They began as assistant to judges, Now many are high ranking legal experts allowed to issue fatwas (See Fatwas Under Muslim Law). The top Islamic authorities as of 2021 in Saudi Arabia was Grand Mufti Sheikh Abdulaziz Al Sheikh. Sunni Islam’s top religious leader in Lebanon was Grand Mufti Sheikh Abdul-Latif Derian,

Respected clerics typically give a sermon at Friday prayers . They also give lectures and conduct question and answer sessions at mosques of religious schools. Religious jobs today are generally low paying. One madrassah teacher told Foreign Policy magazine: “You don’t want to be a mullah like me, with little pay and no respect on the eyes of the rich and powerful.”

Khutbah: the Muslim Sermon

A “khatib” is a Muslim preacher or orator. In the old days he often carried a preaching staff and began his sermons with blessing for Allah, the Prophet and his family and then the current political leader. A “hafiz” is a man who has memorized the Qur’an.

A khutbah is sermon preached by an imam in a mosque at the time of the Friday noon prayer. On its origins, Oleg Graber wrote in his PhD Dissertation: “Today the khutbah is a cultic institution, which traditionally goes back to the Prophet Muhyammad himself. Therefore we have a great wealth of traditions dealing with it. [Source: Oleg Graber, PhD Dissertation, Princeton University, 1955, Chapter I. The Umayyad Royal Idea and its Expression under Mu'awiyah I. Beginning with pg. 18]

“In early Islam the meeting at the mosque known as salat jama'ah, "general prayer," which was to be the nucleus out of which the present day cult developed, was not a religious but a political meeting. Then the expression minbar al-mulk, which connects the seat of the preacher with royal attributes, takes its full meaning of throne, from which the ruler announces to the people new decisions and recent events. Then also the khatib is not simply a preacher, but a political leader or a king, who therefore cannot but sit while addressing his people. The minbar, on which he sits, together with the stick or spear he carries, are remnants from pre-Islamic days, when they were symbols of judicial power. Lammens has shown that Umar, Uthman, Ali, and probably the Prophet himself sat while addressing the assembly of the faithful. Mu'awiyah and the Umayyads are thus exonerated from the accusation of having been the first ones to sit while pronouncing the khutbah.

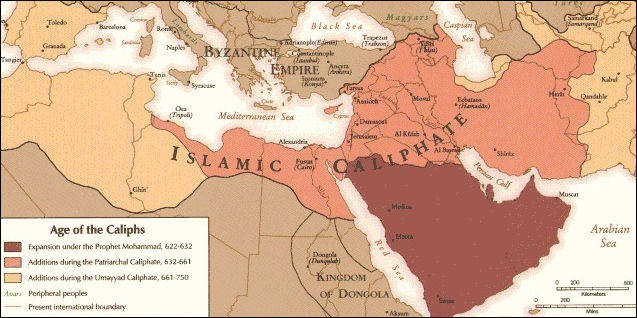

Pan- Islamic Movement and the Caliphate

Some Muslim groups have said one of their goals is to establish a pan-Islamic caliphate throughout the world under Islamic law (sharia). For centuries, from the time of Muhammad’s death to 1924, the Islamic world was unified under the leadership of the caliph the same way the Roman Catholic has been unified under the Pope. A caliph is a successor to the Prophet

Shiite Sheikh Fazlollah Noori In November 1922, the Turks abolished the sultan, who was regarded as the caliph, the leader and unifier of all Sunni Muslims and the last of a line of rulers that dated back to Muhammad. In A.D. 632. There was a brief experiment with a separate caliph but that didn’t work out. In March 1924, the caliphate was abolished. With the deposition of the last caliph in 1924, Islam had no one to speak as its authority. Issues instead were debated by different groups of scholars and jurists that often had competing agendas and interpretations of Islamic scripture.

Robert Hunt of the Dallas Morning News wrote, “There has been a persistent strain of millennialist imperialism withing the larger history of Muslim societies. There has always been Muslims who believe their destiny and that their religion is to finally overcome the ignorant and evil half of the world that has not yet submitted to God as revealed by the Qur’an.

“For most of Islamic history, the millennial empire building gas been displaced by pragmatic agendas of political, military and economic expansion. Actual Muslim empires ultimately abandoned their religious agendas out of both self interest and weakness.”

Harvard political scientist Samuel Huntington, famous for suggesting that differences and conflicts between Islamic and Western societies is based on a “clash of civilizations,” told Islamica magazine: “Certainly there are various trans-Islamic political movements, which try to appeal to Muslims of all societies. But I’m doubtful that there will be any sort of real coherence of Muslim societies as a single political system run by elected r non-elected leaders. But I think we can expect Muslim societies to cooperate with each other on many issues just as Western societies cooperate with each other. I would not rule out the possibility of Muslim, or at least Arab, countries developing some form of organization comparable to the European Union.”

Book: Islamic Imperialism by Efraim Karsh (Yale University Press, 2008)

Islam’s Crisis of Authority

In an article in the Wilson Quarterly, Columbia University historian Richard Bulliet argued that “a crisis of authority had been building in Islam for more than a century” and is the product of religion’s decentralized and weak authority structures which in turn have undermined the power of the traditional ulema (the leading Muslim scholars) who were once able “to disqualify or overrule a man who does not speak — or act — for Islam.” [Source: Jay Tolson, U.S. News and World Report, April 16, 2007]

Bulleit argues tat there are three reason for this: 1) the gradual marginilization of the leading sheiks and muftis because of their closer relationship with authoritarian regimes that control the purse strings to important mosques; 2) the emergence of self-proclaimed authorities with little traditional learning but with superior mastery of the media; and 3) increased literary which has created a huge and receptive audience for new voices [Ibid]

There have been other crises of authority in the past such as when the four main schools of Islam emerged out a anarchic and chaotic proliferation of viewpoint and ideology in medieval times. The main sources today are: 1) the Muslim diaspora in Europe and North America, that includes of Switzerland-based Tariq Ramadan and Iranian-born and Netherlands-based Afshin Elain; 2) activists at universities in predominately Muslim countries outside the Middle East that combines traditional religious studies and with modern studies; and 3) Islamic political parties.

Muslim Authorities

Shiite clerics Since the abolishment of the caliphate and deposition of the last caliph in 1924 Sunni Islam has had a serious void of central leadership and no one to speak as its authority. Issues instead have been debated by different groups of scholars and jurists that often had competing agendas and interpretations of Islamic scripture.

Al Azhar in Cairo is regarded as the most important religious center in the Sunni Muslim world. Founded in A.D. 970, it is also considered the world's oldest still-functioning university. The Grand Sheik (leader) of Al Azhar is regarded by many as the top Islamic authority in the world. His declarations and opinions on matters ranging from Israel to birth control are given much weight. The only catch is that he is appointed by the Egyptian government and conservative Islamists don't like that.

The Grand Mufti is the second-highest ranking cleric and a subsidiary figure who holds a set in the Egyptian government. Al-Azhar contains a Islamic Research and a Fatwa House, which reports directly to the Grand Mufti. Grand Mufti Sheik Abdul-Aziz al-Sheik is Saudi Arabia’s top religious authority. He is the head of the Council of Ulemas, made up of senior Islamic scholars. The members are selected by the council with the approval of the king. The regard themselves as the guardians of society and uphold of Islamic morality. Saudi Arabia’s Grand Mufti once announced that the world was flat and has banned Pokemon on the grounds it is harmful to Islam.

Muslim Religious Training

Beginning in the 10th century special academies were set up for teaching religious and legal doctrines. Al-Azhar, the world’s oldest functioning university, was one of these. Muslim religious training often takes around a dozen years and begins in the early teens. Students learn techniques of preaching. Studying to be a cleric has traditionally been a way on which a young man from a poor or middle class family could improve his station in life.

.jpg) Charles F. Gallagher wrote in the “International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences”: The growth of Islam’s organizational structure and leadership is intimately connected with the development of the holy law and the appearance of the orthodox legal schools in the eighth and ninth centuries. At first they were individual members of the still informal religious institution of Islam, but as this solidified they tended to come together as the formal representatives of the community in questions of faith and, in so doing, often found themselves in positions of opposition to the state. From Abbasid times on, however (after A.D. 750), the political authorities attached theologians to themselves and gave many of them official positions, so that overt opposition by members of the religious establishment tended to be muted. [Source: Charles F. Gallagher, “International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences”, 1960s, Encyclopedia.com]

Charles F. Gallagher wrote in the “International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences”: The growth of Islam’s organizational structure and leadership is intimately connected with the development of the holy law and the appearance of the orthodox legal schools in the eighth and ninth centuries. At first they were individual members of the still informal religious institution of Islam, but as this solidified they tended to come together as the formal representatives of the community in questions of faith and, in so doing, often found themselves in positions of opposition to the state. From Abbasid times on, however (after A.D. 750), the political authorities attached theologians to themselves and gave many of them official positions, so that overt opposition by members of the religious establishment tended to be muted. [Source: Charles F. Gallagher, “International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences”, 1960s, Encyclopedia.com]

With the establishment of religious colleges (singular, madrasah) in the eleventh century A.D., in which courses were given and degrees granted, there was a further formalization of the structure, which reached its height in the complex government-supported theological institutions of the Ottoman Empire. Such developments tended inevitably to limit the independence of the religious establishment with respect to the authorities, and there are manifold examples of subservience and abasement. Nevertheless, throughout Islamic history there runs the principle, however often violated, that the religious institution exists apart from and as a check on the ruling institution. The theologian and the jurist were in the end the guardians of the law for the state, although they were independent of it and at times in opposition to it. The most notable limitation on the power of the state at all times has been the theoretical inviolability of official members of the religious institution and of their property. A large quantity of mortmain property lay, and still lies, in their hands, and by these means mosques, schools, hospitals, and the like were supported, and to a certain extent the independence of the judge protected.

See Separate Article: MUSLIM EDUCATION, MADRASSAHS, ISLAMIC SCHOOLS africame.factsanddetails.com

Muslim Missionaries

There is a missionary aspect of Islam but it is not as strong it the one in Christianity, especially among evangelical ones, but is stronger than the one in Judaism, which has traditionally frowned upon proselytizing. Among the Muslim missionaries are the Tablighi Jamaat (“the group that propagates the faith”), a global network of part time preachers that dress in white robes and leather sandals like prophets and travel in small groups. Their annual gatherings in India and Pakistan attract hundreds of thousands.

Muslims are encouraged to win new converts with the repeated command to “strive in the path of God, until allegiance to God is victorious over all allegiance.” Even so proselytizing is not a big part of Islam, which condemns forced conversions. One famous passage from the Qur’an goes: "There is no conversion in matters of faith!” (2:256)

The Economist reported: “Muslim “missionary” activity is aimed more at reinvigorating the faithful, and encouraging them to greater zealotry than at winning new souls.” The mission of Islamic-oriented television and radio stations, charities and NGOs is more to improve the conditions of existing Muslim communities and build the faith of their members. When there is missionary zeal it is often more to promote a particular sect or set of beliefs than pushing Islam itself.

The growth in the number of Muslims is mostly the product of population growth and migrations rather than conversion.

Muslim NGOs, Technology and the Spread of Islam

.jpg)

Indonesian madrassah students in 1906 Modern technology, globalization and an endless supply of oil money have helped spread Islam at an unprecedented rate. Qur’ans are distributed through a vast network of mosques and even through embassies. There is a wealth of material available on the Internet. Just go to FreeQur’an. com and you can have a Qur’an delivered to you home for free. There are a number of iPod tools that aid the faithful in memorizing passages from the Qur’an.

Saudi oil money is behind much of the missionary work. The Saudi government gives out about 30 million Qur’ans a years, providess funds to build mosques, madrassahs, brings in foreign imam, offers free Arabic classes, opens kindergartens, grocery stores and bookstores, and sets up charities and distributes food to the needy. Billions of dollars is also provided by wealthy individuals through Islamic charities. The money doesn’t just go to developing countries either. By some estimates 50 percent of mosques in the United States receive some foreign funding, mostly from Saudi Arabia.

The Saudis often push their conservative brand of Wahhabi Islam. The Somalia-born Islamic reformer Ayaan Ali Hirsi wrote in the New York Times, “When Saudi and other Gulf philanthropy reached us in Africa, I remember that the building of mosques and donations to hospitals and the poor went hand in hand with the cursing of Jews. Jews were said to responsible for the deaths of babies, epidemics like AIDS, and the cause of war.”

In recent years, the work of Islamic missionaries and charities has been crippled by the “war on terrorism,” which has made distributing Qur’ans and travel by imam more difficult. Contributions to Muslim charities have dropped and several charities have had their funding disrupted by bank account freezes and investigations. Efforts by Christians to do missionary work in traditionally Muslim areas is often greeted with great hostility. Saudi Arabia does not allow Bibles to be distributed on its soil. In other places missionaries have been sent to prison. Muslims that renounce their religion have been accused apostasy, a Sharia crime punishable by death.

See Apostasy, Sharia, Muslim Government

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, Encyclopedia.com, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, Al Jazeera, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Library of Congress and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024