Home | Category: Colonialism and Slavery / Colonial Period in the Middle East

TYPES OF SLAVES IN THE MUSLIM WORLD

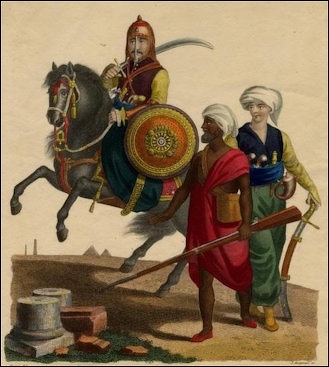

Meccan merchant and his Circassian slave

Bernard Lewis wrote in “Race and Slavery in the Middle East”: “Slaves were employed in a number of functions -- in the home and the shop, in agriculture and industry, in the military, as well as in specialized tasks. The Islamic world did not operate on a slave system of production, as is said of classical antiquity, but slavery was not entirely domestic either. Slave laborers of various kinds were of some importance in medieval times, especially where large-scale enterprises were involved, and they continued to be into the nineteenth century. The most important slaves, however, those of whom we have the fullest information, were domestic and commercial, and it is they who were the characteristic slaves of the Muslim world. They seem to have been mainly blacks, with some Indians, and some whites. ln later times, for which we have more detailed evidence, it would seem that while the slaves often suffered appalling privations from the moment of their capture until their arrival at their final destination, once they were placed with a family they were reasonably well treated and accepted in some degree as members of the household. In commerce, slaves were often apprenticed to their masters, sometimes as assistants, sometimes advancing to become agents or even business partners. [Source: Bernard Lewis, “Race and Slavery in the Middle East,” Chapter 1 Slavery, Oxford University Press 1994. Bernard Lewis (born 1916), an eminent Princeton historian, coined the term “clash of civilizations’ and wrote over 20 books about Arabs and the Middle East, |]

“The slave and also the liberated ex-slave played an important part in domestic life. Eunuchs were required for the protection and maintenance of harems, as confidential servants, as palace staff, and also as custodians of mosques, tombs, and other sacred places. Slave women were required mainly as concubines and as menials. A Muslim slaveowner was entitled by law to the sexual enjoyment of his slave women. While free women might own male slaves, they had of course no equivalent right. |

“The economic exploitation of slaves, apart from some construction work, took place mainly in the countryside, away from the cities, and like almost everything else about rural life is sparsely documented. The medieval Islamic world was a civilization of cities. Both its law and its literature deal almost entirely with townspeople, their lives and problems, and remarkably little information has come down to us concerning life in the villages and the countryside. Sometimes a dramatic event like the revolt of the Zanj in southern Iraq or an occasional passing reference in travel literature sheds a sudden light on life in the countryside. Otherwise, we remain ignorant of what was happening outside the cities until the sixteenth century, when for the first time the surviving Ottoman archives make it possible to follow in some detail the life and activities of rural populations -- and the exploration of this material has still barely begun. The common view of Islamic slavery as primarily domestic and military may therefore reflect the bias of our documentation rather than the reality. There are occasional references, however, to large gangs of slaves, mostly black, employed in agriculture, in the mines, and in such special tasks as the drainage of marshes. Some, less fortunate, were hired out by their owners for piecework. These working slaves had a much harder life.

captives on their way to becoming slaves

The most unfortunate of all were those engaged in agricultural and other manual work and large-scale enterprises, such as for example the Zanj slaves used to drain the salt flats of southern Iraq, and the blacks employed in the salt mines of the Sahara and the gold mines of Nubia. These were herded in large settlements and worked in gangs. Large landowners, or crown lands, often employed thousands of such slaves. While domestic and commercial slaves were relatively well-off, these lived and died in wretchedness. Of the Saharan salt mines it is said that no slave lived there for more than five years. The cultivation of cotton and sugar, which the Arabs brought from the East across North Africa and into Spain, most probably entailed some kind of plantation system. Certainly, the earliest relevant Ottoman records show the extensive use of slave labor in the state-maintained rice plantations. Some such system, for cultivation of cotton and sugar, was taken across North Africa into Spain and perhaps beyond. While economic slave labor was mainly male, slave women were sometimes also exploited economically. The pre-lslamic practice of hiring out female slaves as prostitutes is expressly forbidden by Islamic law but appears to have survived nonetheless. |

“The military slaves were in a sense the aristocrats of the slave population. By far the most important among these were the Turks imported from the Eurasian steppe, from Central Asia, and from what is now Chinese Turkistan. A similar position was occupied by Slavs in medieval Muslim Spain and North Africa and, later, by slaves of Balkan and Caucasian origin in the Ottoman Empire. Black slaves were occasionally employed as soldiers, but this was not common and was usually of brief duration. |

“Certainly the most privileged of slaves were the performers. Both slave boys and slave girls who revealed some talent received musical, literary, and artistic education. In medieval times most singers, dancers, and musical performers were, at least in origin, slaves. Perhaps the most famous was Ziryab, a Persian slave at the court of Baghdad who later went to Spain, where he became an arbiter of taste and is credited with having introduced asparagus to Europe. Not a few slaves and freedmen have left their names in Arabic poetry and history. |

“In a society where positions of military command and political power were routinely held by men of slave origin or even status and where a significant proportion of the free population were born to slave mothcrs, prejudice against the slave as such, of the Roman or American type, could hardly develop. Where such prejudice and hostility appear -- and they are often expressed in literature and other evidence -- they must be attributed to racial more than to social distinction. The developing pattern of racial specialization in the use of slaves must surely have contributed greatly to the growth of such re judice.” |

Websites and Resources: Islam Islam.com islam.com ; Islamic City islamicity.com ; Islam 101 islam101.net ;Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Religious Tolerance religioustolerance.org/islam ; BBC article bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/islam ; Patheos Library – Islam patheos.com/Library/Islam ; University of Southern California Compendium of Muslim Texts web.archive.org ; Encyclopædia Britannica article on Islam britannica.com ; Islam at Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Islam from UCB Libraries GovPubs web.archive.org ; Muslims: PBS Frontline documentary pbs.org frontline ; Discover Islam dislam.org ;

Islamic History: Islamic History Resources uga.edu/islam/history ; Internet Islamic History Sourcebook fordham.edu/halsall/islam/islamsbook ; Islamic History friesian.com/islam ; Islamic Civilization cyberistan.org ; Muslim Heritage muslimheritage.com ; Brief history of Islam barkati.net ; Chronological history of Islam barkati.net

Elite Slavery in Muslim Societies

Mamluk leading his horse

The Mamluk system was a form of elite slavery. According to the BBC: “Something particular to Islamic slave systems was the creation of a slave elite in some Muslim societies that allowed individuals to achieve considerable status, and even power and wealth, while still remaining in some form of 'enslavement'. [Source: BBC, September 7, 2009 |::|]

Leslie P. Peirce wrote in “The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire”: “The slave elite had enormous value to their Muslim masters because they were a military and administrative group made up of 'outsiders' who didn't have tribal and family allegiances that could conflict with their loyalty to their masters. It was believed that a corps of highly trained slaves loyal only to the ruler and dependent entirely on his good will would serve the state more reliably and efficiently than a hereditary nobility, whose interests might compete with those of the ruler. [Source: Leslie P. Peirce, The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire, 1993 |::|

“Elite slavery is something of a paradox: how can a person have power and hold high office and yet still keep the status of a slave? One answer is that the slave gets authority and high office because they are dependant on the person who gives them their authority and status and who could remove that status if they chose. Thus elite slaves must give total loyalty and obedience to their master in order to maintain their privileges. |::|

“Another view is that the slave who achieves elite status is no longer really a slave, and is able to use their position and power to free themselves of many of the limitations of slavery. This is less convincing since even elite slaves are at risk of losing their privileged status until they break free completely. |::|

“The dependency was not all one way - the masters in many ways relied on their elite slaves, because those slaves were the only people they could really trust. And there was another reason why elite slaves were valuable - precisely because they were slaves, the elite slaves were free of some of the restrictions that limited free people, and this allowed them to do things for their masters that their masters could not otherwise achieve. Two examples of elite slavery were the Mamluks and the Devshirme system. |::|

Mamluk System

Mamluk training

According to the BBC: “Mamluks were originally soldiers captured in Central Asia, but later boys aged 12-14 were specifically taken or bought to be trained as slave soldiers. Their slave status was shown by the name 'Mamluk' which means 'owned'. The Mamluk system became firmly established in the Abbasid Empire during the 9th century. [Source: BBC, September 7, 2009 |::|]

Michael Winter wrote in “Egyptian Society under Ottoman Rule”: “Although the Mamluks were not free men (they could not, for example, pass anything on to their children) they were elite slaves who were held in high regard as professional soldiers loyal to their Islamic masters. Historians have been fascinated by the uniqueness of the Mamluk phenomenon. It was inhuman in some respects (for example, Mamluks being denied the opportunity to bequeath their positions and privileges to their sons), yet it provided Islam with a superb military force and a sophisticated political system. [Source: Michael Winter, Egyptian Society under Ottoman Rule, 1517-1798, 1992]

“The basic ideal of military slavery - the Mamluk's total loyalty to his master who had bought, trained, maintained and freed him - was a pillar of Mamluk society in Ottoman Egypt, as it had been in the Mamluk Sultanate. When the master decided that his Mamluk had reached maturity and was ready to assume an office, he set him free, and 'allowed him to grow his beard.' He was now a free man, no longer dependent. The master often appointed these former slaves to army posts, to the beylicate [the beys were high ranking emirs who held important positions in Egyptian government], or to the regimental command. Very often, the master decided whom his former slave would marry, a decision which could advance the Mamluk socially and financially.”

Devshirme System

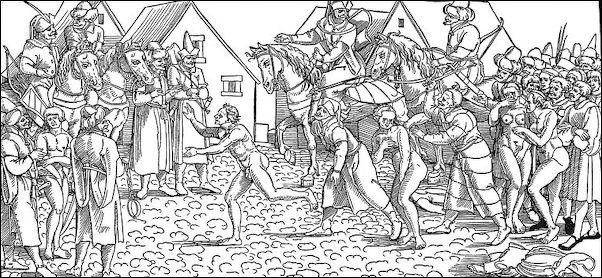

According to the BBC: “Non-Muslims in parts of the empire had to hand over some of their children as a tax under the devshirme ('gathering') system introduced in the 14th century. Conquered Christian communities, especially in the Balkans, had to surrender twenty percent of their male children to the state. To the horror of their parents, and Western commentators, these children were converted to Islam and served as slaves. [Source: BBC, September 4, 2009 |::|]

blood tax

“Although the forced removal from their families and conversion was certainly traumatic and out of line with modern ideas of human rights, the devshirme system was a rather privileged form of slavery for some (although others were undoubtedly ill-used). |::|

“Some of the youngsters were trained for government service, where they were able to reach very high ranks, even that of Grand Vezir. Many of the others served in the elite military corps of the Ottoman Empire, called the Janissaries, which was almost exclusively made up of forced converts from Christianity. |::|

“The devshirme played a key role in Mehmet's conquest of Constantinople, and from then on regularly held very senior posts in the imperial administration. Although members of the devshirme class were technically slaves, they were of great importance to the Sultan because they owed him their absolute loyalty and became vital to his power. This status enabled some of the 'slaves' to become both powerful and wealthy. Their status remained restricted, and their children were not permitted to inherit their wealth or follow in their footsteps. The devshirme system continued until the end of the seventeenth century.” |::|

Eunuchs

According to the BBC: “Male slaves who had had their sexual organs removed were called eunuchs, and played an important part in some Muslim societies (as they did in some other cultures). They had the advantage for their masters of not being subject to sexual influence, and as they were unlikely to marry, they had no family ties to hinder their devotion to duty. [Source: BBC, September 7, 2009 |::|]

“Eunuch slavery involved compulsory mutilation, which usually took place between the ages of 8 and 12. Without modern medical skills and anaesthetics this was painful, and often led to fatal complications, and sometimes to physical or psychological problems for those who survived the operation. |::|

“Eunuchs had a particular role as guardians of the harem and were the main way in which the women of the harem had contact with the world outside. |::|

“In the Ottoman Empire eunuchs from Africa held considerable power from the mid sixteenth century to the eighteenth. It's recorded that the Ottoman family owned 194 eunuchs as late as 1903, of whom 35 'bore a title of some seniority'. Eunuchs could also play important military roles. |::|

Concubinage and Sexual Slavery in Muslim Societies

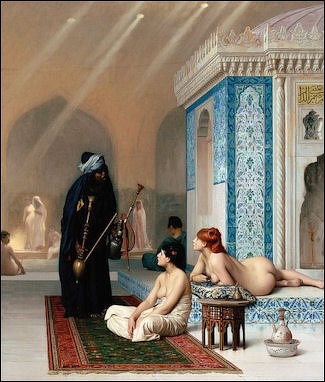

an odalisque: a female slave or concubine in a harem, especially one in the seraglio of the Sultan of Turkey

According to the Encyclopaedia of Islam: “Concubinage may be defined as the more or less permanent cohabitation (outside the marriage bond) of a man with a woman or women, whose position would be that of secondary wives, women bought, acquired by gift, captured in war, or domestic slaves.”

In the Ottoman Empire the sale of woman as slaves continued until 1908. The BBC says: “Muslim cultures are thought to have had more female slaves than male slaves. Enslaved women were given many tasks and one of the most common was working as a domestic servant. But some female slaves were forced to become sex workers: not prostitutes, as this is forbidden in Islam, but concubines. Concubines were women who were sexually available to their master, but not married to him. A Muslim man could have as many concubines as he could afford. [Source: BBC, September 7, 2009 |::|]

“Being a concubine did have some benefits: if a slave woman gave birth to her owner's child, her status improved dramatically - she could not be sold or given away, and when her owner died she became free. The child was also free and would inherit from their father as any other children. |::|

“Concubinage was not prostitution in the commercial sense both because that was explicitly forbidden and because only the owner could legitimately have sex with a female slave; anyone else who had sex with her was guilty of fornication. Concubinage was not unique to Islam; the Bible records that King Solomon and King David both had concubines, and it is recorded in other cultures too.” |::|

Harem Women

Harem women were essentially concubines who lived in the harem, an area of the household where women lived separately from men. According to Ehud R Toledano: 1) The harem system grew out of the need in Ottoman society to achieve gender segregation and limit women's accessibility to men who did not belong to their family. 2) Households were divided into two separate sections: the selamlik, housing the male members, and the haremlik, where the women and children dwelt. 3) At the head of the women's part reigned the master's mother or his first wife (out of a maximum of four wives allowed by Islam). [Source: Ehud R. Toledano, “Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle East, 1998,” the BBC |=|]

harem pool with women and a eunuch

4) The concubines were also part of the harem, where all the attendants were women. Male guests of the master were not entertained in the harem. 5) An active and well-developed social network linked harems of similar status across Ottoman towns and villages; mutual visits and outdoor excursions were common. 6) For the women who actually spent their lives in the harems, reality was, of course, far more mixed and complicated.

7) The women who came into the harem as slaves (câriyes) were taught and trained to be "ladies," learning all the domestic and social roles attached to that position. As they grew up, they would be paired with the men of the family either as concubines or as legal wives. 8) However, harem slaves' freedom of choice was rather limited, as was that of women in general in an essentially male-dominated environment. Harem slaves frequently had to endure sexual harassment from male members of the family. |=

According to the BBC: “Writers disagree over the nature of concubinage and the harem: 1) Some argue that it was seriously wrong in that; 2) it was just slavery; 3) it breached human rights; 3) it exploited women; 4) women could be bought and sold, or given as gifts; 5) it involved compulsory non-consensual sex - which would nowadays be called 'rape'; 5) it reinforced male power in the culture; 6) Others say that it was relatively benign, because; 7) it gave female slaves a relatively easy existence; 8) it gave female slaves a chance to rise socially; 9) it gave female slaves a chance to gain power; 10) it gave female slaves a chance to gain their freedom. [Source: BBC, September 7, 2009 |::|]

“A balanced view might be to say that sexual slavery in this context was a very bad thing, but that it was possible for some of the more fortunate victims to gain benefits that provided some degree of compensation. |::|

Political Role of Concubines in the Ottoman Empire

Concubines sometimes played important political roles and wielded direct political influence government policy. Leslie P. Peirce wrote in “The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire”: “More than any other Muslim dynasty, the Ottomans raised the practice of slave concubinage to a reproductive principle: after the generations of Osman and Orhan, virtually all offspring of the sultans appear to have been born of concubine mothers.” [Source: Leslie P. Peirce, “The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire,” 1993]

According to the BBC: “The benefit to the state, or at least to the ruling dynasty, of having the ruling line born through concubines rather than wives was that only one family was involved - the family of a concubine was irrelevant, but the family of a wife would expect to gain power and influence through their relationship to the mother of the son. These conflicting interests could threaten the succession and weaken the ruling family. (This didn't eliminate conflict between heirs and families altogether, but it probably reduced it.) [Source: BBC, September 7, 2009 |::|]

“Concubines as well as wives also played an important role in strengthening cohesion, stability, and continuity at household level too, as this remark about 18th century Cairo demonstrates. Mary Ann Fay wrote: “Marital and nonmarital unions strengthened the links among men; women legitimized the succession of men to power, and women's property ownership added to the overall wealth, prestige, and power of a household. [Source: Mary Ann Fay, “From Concubines to Capitalists: Women, Property, and Power in Eighteenth-century Cairo,” Journal of Women's History, 1998]

“However, the harem was not a prison; it was instead the family quarters of an upper-class home which became exclusively female space when men not related to the women were in the house and whose entry into the harem was forbidden. Women, heavily veiled, could and did leave their homes...Women were not imprisoned in the harem or in the veils and cloaks that concealed their bodies and faces on the street, but both customs were important signifiers of women's lack of sexual autonomy and of men's control over the selection of women's sexual and marital partners. In the economic sphere, however, women had a great deal of autonomy... Therefore, the eighteenth-century Egyptian household should not be seen as the site of unrelieved oppression of women but rather in terms of asymmetries of power between men and women.”

Military Slaves in the Muslim World

Bernard Lewis wrote in “Race and Slavery in the Middle East”: The military slave, who bears arms and fights for his owner, was a known but not common figure in antiquity. In the late fifth and early fourth centuries B.C., the city of Athens was policed by a corps of armed Scythian slaves, originally numbering some three hundred, who were the property of the city. Some Roman dignitaries had armed slave bodyguards; some owned gladiators, as men in other times might own gamecocks or racehorses, but in general the Greeks and Romans did not approve of the use of slaves in combatant duties. It was not until the medieval Islamic state that we find military slaves in significant numbers, forming a substantial and eventually predominant component in their armies. [Source: Bernard Lewis, “Race and Slavery in the Middle East,” Chapter 9 Slaves in Arms, Oxford University Press 1994. Bernard Lewis (born 1916), an eminent Princeton historian, coined the term “clash of civilizations’ and wrote over 20 books about Arabs and the Middle East.|]

Mamluk military slaves

“The professional slave soldier, so characteristic of later Islamic empires, was not present in the earliest Islamic regimes. There were indeed slaves who fought in the army of the Prophet, but they were there as Muslims and as loyal followers, not as slaves or professionals. Most of them were freed for their services, and according to an early narrative, when the Prophet appeared before the walls of the Hijaz town of Ta'if, he sent a crier to announce that any slave who came out and joined him would be free. Abu Muslim, the first military leader of the Abbasid revolution which transformed the Islamic state and society in the mid-eighth century, appealed to slaves to come and join him and offered freedom to those who responded. So many, we are told, answered his call that he gave them a separate camp and formed them into a separate combat unit. During the great expansion of the Arab armies and the accompanying spread of the Islamic faith in the seventh and early eighth centuries, mally of the peoples of the conquered countries were captured, enslaved, convcrted, and liberated, and great numbers of these joined the armies of Islam. Iranians in the East, Berbers in the West, reinforced the Arab armies and contributed significantly to the further advance of Islam, eastward into Central Asia and beyond, westward across North Africa and into Spain. These were, however, not slaves but freedmen. Though their status was at first inferior to that of freeborn Arabs, it was certainly not servile, and in time the differences in rank, pay, and status between free and freed soldiers disappeared. As so often, the historiographic tradition foreshortens this development and attributes it to a decree of the Caliph 'Umar, who is said to have ordered his governors to make the privileges and duties of manumitted and converted recruits "among the red people" the same as those of the Arabs. "What is due to these, is due to those; what is due from these, is due from those." The limitation of this concession to the "red people," a term commonly applied by the Arabs to the Iranians and later extended to their Central Asian neighbors, is surely significant. The recruitment of aliens, that is, non-Arabs and often non-Muslims, was by no means restricted to liberated captives, and the distinction between freed subjects, free mercenaries, and bought barbarian slaves is often tenuous. |

“In recruiting barbarians from the "martial races" beyond the frontiers into their imperial armies, the Arabs were doing what the Romans and the Chinese had done centuries before them. In the scale of this recruitment, however, and the preponderant role acquired by these recruits in the imperial and eventually metropolitan forces, Muslim rulers went far beyond any precedent. As early as 766 a Christian clergyman writing in Syriac spoke of the "locust swarm" of unconverted barbarians -- Sindhis, Alans, Khazars, Turks, and others -- who served in the caliph's army. In the course of the ninth century, slave armies appeared all over the Islamic empire. Sometimes, as in North Africa and later Egypt, they were recruited by ambitious governors seeking to create autonomous and hereditary principalities and requiring troops who would be loyal to them against their immediate subjects and their imperial suzerains. Sometimes it was the caliphs themselves who recruited such armies. Such, for example, were the palace guards recruited by the Umayyad Caliph al-Hakam in Cordova and the Abbasid Caliph al-Mu'tasim in Iraq. |

“This was a new institution in Islam. The patriarchal caliphs, and their successors for more than a hundred years, had no slave praetorian guards, but were protected in their palace by a small force of free Arabs and, under the early Abbasids, freed soldiers and their descendants from Khurasan. Within a remarkably short time, the slave palace guard became the norm for Muslim rulers, and rapidly developed into a slave army, serving both to maintain the ruler in his palace and his capital and, for a sultan, to uphold his imperial authority in the provinces. In the East, slave soldiers were recruited mainly among the Turkish and to a lesser extent among the Iranian peoples of the Eurasian steppe and of Central and inner Asia; in the West, from the Berbers of North Africa and from the Slavs of Europe. Some soldiers, particularly in Egypt and North Africa, were brought from among the black peoples farther south. As the frontiers of Islam steadily expanded through conversion and annexation, the periphery was pushed farther and farther away, and the enslaved barbarians came from ever-remoter regions in Asia, Africa, and, to a very limited extent, Europe. |

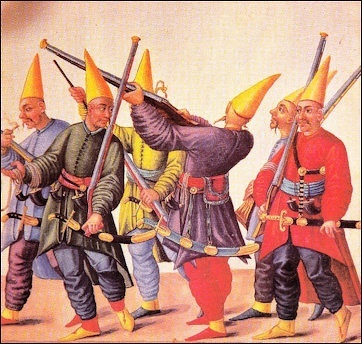

Janissarries, Ottoman military slaves

“Some of these soldiers were captured in wars, raids, and forays. The more usual practice, however, was for them to be purchased, for money, on the Islamic frontiers. It was in this way that Muslims bought and imported the Central Asian Turks who came to constitute the vast majority of eastern Muslim armies. Captured and sold to the Muslims at a very tender age, they were given a careful and elaborate education and training, not only in the military arts but also in the norms of Islamic civilization. From their ranks were drawn the soldiers, then the officers, and finally the commanders of the armies of Islam. From this it was only a step to the ultimate paradox, the slave kings who ruled in Cairo, in Delhi, and in other capitals. Even the Ottomans, though themselves a freeborn imperial dynasty, relied for their infantry on the celebrated slave corps of Janissaries, and most of the sultans were themselves sons of slave mothers. |

“While the slave in arms was, with few exceptions, an Islamic innovation, the slave in authority dates back to remote antiquity. Already in Sumerian times, kings appointed slaves to positions of prestige and even power -- or, perhaps more accurately, treated certain of their court functionaries as royal slaves. Different words were used to denote such privileged slaves, distinct from those applied to the menial and laboring generality. Under the Abbasid caliphs and under later Muslim dynasties, men of slave origin, usually but not always manumitted, figured prominently in the royal entourage. The system of court slavery reached its final and fullest development in the Ottoman Empire, where virtually all the servants of the state, both civil and military, had the status of kul, "slave," of the Gate, that is, of the sultan. The only exceptions were the members of the religious establishment. The Ottoman kul was not a slave in terms of Islamic law, and was free from most of the restraints imposed on slaves in such matters as marriage, property, and legal responsibility. He was, however, subject to the arbitrary power of the sultan, who was free to dispose of his assets, his person, and his life in ways not permitted by the law in relation to free- or freedmen. This perception of the status of political officeholders and their relationship to the supreme sovereign power was of course by no means limited to the Ottoman Empire, or indeed to the Islamic world.

Explanation for the Use of Military Slaves in the Muslim World

Bernard Lewis wrote in “Race and Slavery in the Middle East”: “Various explanations have been offered for the reliance of Muslim sovereigns on slave armies. An obvious merit of the military slave, for the kings or generals who owned him, was his habit of prompt and unquestioning obedience to orders -- a quality less likely to be found among freeborn volunteers or even among conscripts, in the relatively few times and places when conscription was known or feasible before the nineteenth century. Perhaps the most convincing explanation of the growth of the slave armies is the eternal need of autocratic rulers for an armed force which would support and maintain their rule yet neither limit it with intermediate powers nor threaten it with the challenge of opposing loyalties. An army constantly renewed by slaves imported from abroad would form no hereditary nobility; an army manned and commanded by aliens could neither claim nor create any loyalties or bases of support among the local population. [Source: Bernard Lewis, “Race and Slavery in the Middle East,”Chapter 9 Slaves in Arms, Oxford University Press 1994 |]

“Such soldiers, it was assumed, would have no loyalty but to their masters, that is, to the monarchs who bought and employed them. But their loyalty, all too often, was to the regiment and to its commanders, many of whom ultimately themselves became kings. The mamluk sultans and emirs who ruled Egypt, Syria, and western Arabia for two-and-a-half centuries, until the Ottoman conquest in 1517, rigorously excluded their own freeborn and locally born offspring from the apparatus of political and military power, including even the sultanate itself. They nevertheless succeeded in maintaining their system for centuries. In part, the common bond of mamluk regiments was ethnic. Many regiments, and the quarters which they inhabited, were based on ethnic and even tribal groups. But in the main, the bond was social rather than racial. At a certain stage in his career, the mamluk was emancipated, and, on becoming a freeman, himself bought and owned mamluks who, rather than his physical sons, were his true successors. The most powerful bond and loyalty, within the mamluk system, was that owed by the slave to his master, and, after manumission, by the freedman to his patron. |

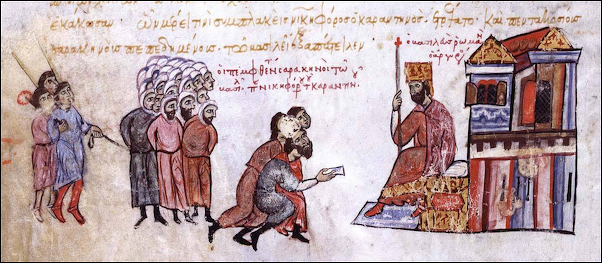

Arab captives brought before Byzantine Emperor Romanos III in the 11th century

“In the military sense, the slave armies were remarkably effective. In the later Middle Ages, it was the mamluks of Egypt who finally defeated and expelled the Crusaders and halted the Mongol advance across the Middle East, the Ottoman Janissary infantry who conquered Southeastern Europe. It was in accordance with the logic of the system that the mamluk armies of Egypt consisted mainly of slaves imported from the Turkish and Circassian peoples of the Black Sea area, while the Ottoman Janissaries were recruited mainly from the Slavic and Albanian populations of the Balkans. |

“Ibn Khaldun, surely the greatest of all Arab historians, writing in the fourteenth century, saw in the coming of the Turks and in the institution of slavery by which they came, the manifestation of God's providential concern for the safety and survival of the Muslim state and people: |

“"When the [Abbasid] state was drowned in decadence and luxury. . . and overthrown by the heathen Tatars . . . because the people of the faith had become deficient in energy and reluctant to rally in defense . . . then it was God's benevolence that He rescued the faith by reviving its dying breath and restoring the unity of the Muslims in the Egyptian realms.... He did this by sending to the Muslims, from among this Turkish nation and its great and numerous tribes, rulers to defend them and utterly loyal helpers, who were brought . . . to the House of Islam under the rule of slavery, which hides in itself a divine blessing. By means of slavery they learn glory and blessing and are exposed to divine providence; cured by slavery, they enter the Muslim religion with the firm resolve of true believers and yet with nomadic virtues unsullied by debased nature, unadulterated by the filth of pleasure, undefiled by ways of civilied living, and with their ardor unbroken by the profusion of luxury.... Thus one intake comes after another and generation follows generation, and Islam rejoices in the benefit which it gains through them, and the branches of the kingdom flourish with the freshness of youth." |

Race and Muslim Military Slaves

Bernard Lewis wrote in “Race and Slavery in the Middle East”: “Most of the military slaves of Islam were white -- Turks and Caucasians in the East, Slavs and other Europeans in the West. Black military slaves were, however, not unknown and indeed at certain periods were of importance. Individual black fighting men, both slaves and free, are mentioned as having participated in raiding and warfare in pre-Islamic and early Islamic times. According to the biographies and histories of the Prophet, there were several blacks, both in his army and in the armies of his pagan enemies. One of them, called Wahshi, an Ethiopian slave, distinguished himself in the battles against the Prophet at Uhud and at the Ditch; and later, after the Muslim capture of Mecca, he fought for the Muslims in the wars that followed the death of the Prophet. [Source: Bernard Lewis, “Race and Slavery in the Middle East,”Chapter 9 Slaves in Arms, Oxford University Press 1994 |]

Turks with captives

“Black soldiers appear occasionally in early Abbasid times, and after the slave rebellion in southern Iraq, in which blacks displayed terrifying military prowess, they were recruited into the infantry corps of the caliphs in Baghdad. Ahmad b. Tulun (d. 884), the first independent ruler of Muslim Egypt, relied very heavily on black slaves, probably Nubians, for his armed forces; at his death he is said to have left, among other possessions, twenty-four thousand white mamluks and forty-five thousand blacks. These were organized in separate corps, and accommodated in separate quarters at the military cantonments. When Khumarawayh, the son and successor of Ahmad ibn Tulun. rode in procession, he was followed, according to a chronicler, by a thousand black guards wearing black cloaks and black turbans, so that a watcher could fancy them to be a black sea spreading over the face of the earth, because of the blackness of their color and of their garments. With the glitter of their shields, of the chasing on their swords, and of the helmets under their turbans, they made a really splendid sight. “|

“The black troops were the most faithful supporters of the dynasty, and shared its fate. When the Tulunids were overthrown at the beginning of 905, the restoration of caliphal authority was followed by a massacre of the black infantry and the burning of their quarters: "Then the cavalry turned against the cantonments of the Tulunid blacks, seized as many of them as they could, and took them to Muhammad ibn Sulayman [the new governor sent by the caliph]. He was on horseback, amid his escort. He gave orders to slaughter them, and they were slaughtered in his presence like sheep." |

“A similar fate befell the black infantry in Baghdad in 930, when they were attacked and massacred by the white cavalry, with the help of other troops and of the populace, and their quarters burned. Thereafter, black soldiers virtually disappear from the armies of the eastern caliphate. |

Black Military Slaves in Egypt

Bernard Lewis wrote in “Race and Slavery in the Middle East”: “In Egypt, the manpower resources of Nubia were too good to neglect, and the traffic down the Nile continued to provide slaves for military as well as other purposes. Black soldiers served the various rulers of medieval Egypt, and under the Fatimid caliphs of Cairo black regiments, known as 'Abid al-Shira', "the slaves by purchase," formed an important part of the military establishment. They were particularly prominent in the mid-eleventh century, during the reign of al-Mustansir, when for a while the real ruler of Egypt was the caliph's mother, a Sudanese slave woman of remarkable strength of character. There were frequent clashes between black regiments and those of other races and occasional friction with the civil population. One such inci- dent occurred in 1021, when the Caliph al-Hakim sent his black troops against the people of Fustat (old Cairo), and the white troops joined forces to defend them. A contemporary chronicler of these events describes an orgy of burning, plunder, and rape. In 1062 and again in 1067 the black troops were defeated by their white colleagues in pitched battles and driven out of Cairo to Upper Egypt. Later they returned, and played a role of some importance under the last Fatimid caliphs. [Source: Bernard Lewis, “Race and Slavery in the Middle East,”Chapter 9 Slaves in Arms, Oxford University Press 1994 |]

Moor of Arabia

“With the fall of the Fatimids, the black troops again paid the price of their loyalty. Among the most faithful supporters of the Fatimid Caliphate, they were also among the last to resist its overthrow by Saladin, ostensibly the caliph's vizier but in fact the new master of Egypt. By the time of the last Fatimid caliph, al-'Adid, the blacks had achieved a position of power. The black eunuchs wielded great influence in the palace; the black troops formed a major element in the Fatimid army. It was natural that they should resist the vizier's encroachments. In 1169 Saladin learned of a plot by the caliph's chief black eunuch to remove him, allegedly in collusion with the Crusaders in Palestine. Saladin acted swiftly; the offender was seized and decapitated and replaced in his office by a white eunuch. The other black eunuchs of the caliph's palace were also dismissed. The black troops in Cairo were infuriated by this summary execution of one whom they regarded as their spokesman and defender. Moved, according to a chronicler, by "racial solidarity" (jinsiyya), they prepared for battle. In two hot August days, an estimated fifty thousand blacks fought against Saladin's army in the area between the two palaces, of the caliph and the vizier. |

“Two reasons are given for their defeat. One was their betrayal by the Fatimid Caliph al-'Adid, whose cause they believed they were defending against the usurping vizier: "Al-'Adid had gone up to his belvedere tower, to watch the battle between the palaces. It is said that he ordered the men in the palace to shoot arrows and throw stones at [Saladin's] troops, and they did so. Others say that this was not done by his choice. Shams al-Dawla [Saladin's brother] sent naphtha-throwers to burn down al-'Adid's belvedere. One of them was about to do this when the door of the belvedere tower opened and out came a caliphal aide, who said: "The Commander of the Faithful greets Shams al-Dawla, and says: 'Beware of the [black] slave dogs! Drive them out of the country!'" The blacks were sustained by the belief that al-'Adid was pleased with what they did. When they heard this, their strength was sapped, their courage waned, and they fled." |

“The other reason, it is said, was an attack on their homes. During the battle between the palaces, Saladin sent a detachment to the black quarters, with instructions "to burn them down on their possessions and their children." Learning of this, the blacks tried to break off the battle and return to their families but were caught in the streets and destroyed. This encounter is variously known in Arabic annals as "the Battle of the Blacks" and "the Battle of the Slaves.'' Though the conflict was not primarily racial, it acquired a racial aspect, which is reflected in some of the verses composed in honor of Saladin's victory. Maqrizi, in a comment on this episode, complains of the power and arrogance of the blacks: "If they had a grievance against a vizier, they killed him; and they caused much damage by stretching out their hands against the property and families of the people. When their outrages were many and their misdeeds increased, God destroyed them for their sins." |

Revolts by Black Military Slaves in Egypt

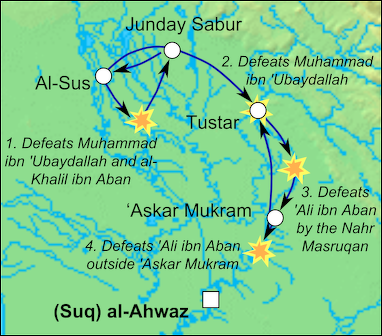

Zanj Rebellion (AD 869–883), a black-slave revolt against the ʿAbbāsid caliphal empire

Bernard Lewis wrote in “Race and Slavery in the Middle East”: “Sporadic resistance by groups of black soldiers continued, but was finally crushed after a few years. While the white units of the Fatimid army were incorporated by Saladin in his own forces, the blacks were not. The black regiments were disbanded, and black fighting men did not reappear in the armies of Egypt for centuries. Under the mamluk sultans, blacks were em- ployed in the army in a menial role, as servants of the knights. There was a clear distinction between these servants, who were black and slaves, and the knights' orderlies and grooms, who were white and free. [Source: Bernard Lewis, “Race and Slavery in the Middle East,”Chapter 9 Slaves in Arms, Oxford University Press 1994 |]

“Though black slaves no longer served as soldiers in Egypt, they still fought occasionally -- as rebels or rioters. In 1260, during the transition from the Ayyubid to the mamluk sultanate, black stableboys and some others seized horses and weapons, and staged a minor insurrection in Cairo. They proclaimed their allegiance to the Fatimids and followed a religious leader who "incited them to rise against the people of the state; he granted them fiefs and wrote them deeds of assignment." The end was swift: "When they rebelled during the night, the troops rode in, surrounded them, and shackled them; by morning they were crucified outside the Zuwayla gate." |

“The same desire among the slaves to emulate the forms and trappings of the mamluk state is expressed in a more striking form in an incident in 1446, when some five hundred slaves, tending their masters' horses in the pasturages outside Cairo, took arms and set up a miniature state and court of their own. One of them was called sultan and was installed on a throne in a carpeted pavilion; others were dignified with the titles of the chief of ficers of the mamluk court, including the vizier, the commander in chief, and even the governors of Damascus and Aleppo. They raided grain caravans and other traffic and were even willing to buy the freedom of a colleague. They succumbed to internal dissensions. Their "sultan" was challenged by another claimant, and in the ensuing struggles the revolt was suppressed. Many of the slaves were recaptured and the rest fled. |

Black Military Slaves in Cavalry and Firearm Units

Bernard Lewis wrote in “Race and Slavery in the Middle East”: “Toward the end of the fifteenth century, black slaves were admitted to units using firearms -- a socially despised weapon in the mamluk knightly society. When a sultan tried to show some favor to his black arquebusiers, he provoked violent antagonism from the mamluk knights, which he was not able to resist. In 1498 "a great disturbance occurred in Cairo." [Source: Bernard Lewis, “Race and Slavery in the Middle East,”Chapter 9 Slaves in Arms, Oxford University Press 1994 |]

The sultan (according to the chronicler) had outraged the mamluks by conferring two boons on a black slave called Farajallah, chief of the firearms personnel in the citadel -- first, giving him a white Circassian slave girl from the palace as wife, and second, granting him a short-sleeved tunic, a characteristic garment of the mamluks: "On beholding this spectacle [says the chronicler] the Royal mamluks expressed their disapproval to the sultan, and they put on their. . . armour. . . and armed themselves with their full equipment. A battle broke out between them and the black slaves, who numbered about five hundred. The black slaves ran away and gathered again in the towers of the citadel and fired at the Royal mamluks. The Royal mamluks marched on them, killing Farajallah and about fifty of the black slaves; the rest fled; two Royal mamluks were killed. Then the emirs and the sultan's maternal uncle, the Great Dawadar, met the sultan and told him: "We disapprove of these acts of yours [and if you persist in them, it would be better for you to ride by night in the narrow by-streets and go away together with those black slaves to far-off places!" The sultan answered: "I shall desist from this, and these black slaves will be sold to the Turkmans." |

“In the Islamic West black slave troops were more frequent, and sometimes even included cavalry -- something virtually unknown in the East. The first emir of Cordova, 'Abd al-Rahman I, is said to have kept a large personal guard of black troops; and black military slaves were used, especially to maintain order, by his successors. Black units, probably recruited by purchase via Zawila in Fezzan (now southern Libya), figure in the armies of the rulers of Tunisia between the ninth and eleventh centuries. Black troops became important from the seventeenth century, after the Moroccan military expansion into the Western Sudan. The Moroccan Sultan Mawlay Ismaili (1672-1727) had an army of black slaves, said to number 250,000. The nucleus of this army was provided by the conscription or compulsory purchase of all male blacks in Morocco; it was supplemented by levies on the slaves and serfs of the Saharan tribes and slave raids into southern Mauritania. These soldiers were mated with black slave girls, to produce the next generation of male soldiers and female servants. The youngsters began training at ten and were mated at fifteen.” |

Civil Wars Between Blacks and Whites in Morocco

Arab slave traders

Bernard Lewis wrote in “Race and Slavery in the Middle East”: “After the sultan's death in 1727, a period of anarchic internal struggles followed, which some contemporaries describe as a conflict between blacks and whites. [Source: Bernard Lewis, “Race and Slavery in the Middle East,”Chapter 9 Slaves in Arms, Oxford University Press 1994 |]

The philosopher David Hume, writing at about the same time, saw such a conflict as absurd and comic, and used it to throw ridicule on all sectarian and factional strife: "The civil wars which arose some few years ago in Morocco between the Blacks and Whites, merely on account of their complexion, are founded on a pleasant difference. We laugh at them; but, I believe, were things rightly examined, we afford much more occasion of ridicule to the Moors. For, what are all the wars of religion, which have prevailed in this polite and knowing part of the world? They are certainly more absurd than the Moorish civil wars. The difference of complexion is a sensible and a real difference; but the controversy about an article of faith, which is utterly absurd and unintelligible, is not a difference in sentiment, but in a few phrases and expressions, which one party accepts of without understanding them, and the other refuses in the same manner.... Besides, I do not find that the Whites in Morocco ever imposed on the Blacks any necessity of altering their complexion . . . nor have the Blacks been more unreasonable in this particular." |

“In 1757 a new sultan, Sidi Muhammad Ill, came to the throne. He decided to disband the black troops and rely instead on Arabs. With a promise of royal favor, he induced the blacks to come to Larache with their families and worldly possessions. There he had them surrounded by Arab tribesmen, to whom he gave their possessions as booty and the black soldiers, their wives, and their children as slaves. "I make you a gift," he said, "of these 'abid, of their children, their horses, their weapons, and all they possess. Share them among you.'' |

Reliance on Black Military Slaves in Egypt and the Ottoman Empire in the 19th Century

Bernard Lewis wrote in “Race and Slavery in the Middle East”: “Blacks were occasionally recruited into the mamluk forces in Egypt at the end of the eighteenth century. "When the supply [of white slaves] proves insufficient," says a contemporary observer, W. G. Browne, "or many have been expended, black slaves from the interior of Africa are substituted, and if found docile, are armed and accoutred like the rest." This is confirmed by Louis Frank, a medical officer with Bonaparte's expedition to Egypt, who wrote an important memoir on the Negro slave trade in Cairo. [Source: Bernard Lewis, “Race and Slavery in the Middle East,”Chapter 9 Slaves in Arms, Oxford University Press 1994 |]

“In the nineteenth century, black military slaves reappeared in Egypt in considerable numbers; their recruitment was indeed one of the main purposes of the Egyptian advance up the Nile under Muhammad 'Ali Pasha (reigned 1805-49) and his successors. Collected by annual razzias (raids) from Darfur and Kordofan, they constituted an important part of the Khedivial armies and incidentally furnished the bulk of the Egyptian expeditionary force which Sa'id Pasha sent to Mexico in 1863, in support of the French. An English traveler writing in 1825 had this to say about black soldiers in the Egyptian army: |

“"When the negro troops were first brought down to Alexandria, nothing could exceed their insubordination and wild demeanour; but they learned the military evolutions in half the time of the Arabs; and I always observed they went through the manoeuvres with ten times the adroitness of the others. It is the fashion here, as well as in our colonies, to consider the negroes as the last link in the chain of humanity, between the monkey tribe and man in intellect; and I do not suffer the eloquence of the slave driver to convince me that the negro is so stultified as to be unfit for freedom. |

“Even in Turkey, liberated black slaves were sometimes recruited into the armed forces, often as a means to prevent their reenslavement. Some of these reached of ficer rank. A British naval report, dated January 25,1858, speaks of black marines serving with the Turkish navy: "They are from the class of freed slaves or slaves abandoned by merchants unable to sell them. There are always many such at Tripoli. I believe the government acquainted the Porte with the embarrassment caused by their numbers and irregularities, and this mode of relief was adopted. Those brought by the Faizi Bari, about 70 in number, were on their arrival enrolled as a Black company in the marine corps. They are in exactly the same position with respect to pay, quarters, rations, and clothing as the Turkish marines, and will equally receive their discharge at the expiration of the allotted term of service. They are in short on the books of the navy. They have received very kind treatment here, lodged in warm rooms with charcoal burning in them day and night. A negro Mulazim [lieutenant] and some negro tchiaoushes [sergeants], already in the service have been appointed to look after and instruct them. They have drilled in the manual exercise in their warm quarters, and have not been set to do any duty on account of the weather. They should not have been sent here in winter. Those among them unwell on their arrival were sent at once to the naval hospital. Two only have died of the whole number. The men in the barracks are healthy and appear contented. No amount of ingenuity can conjure up any conncxion between their condition and the condition of slavery." |

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Arab News, Jeddah; "A History of the Arab Peoples" by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); "Encyclopedia of the World Cultures" edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994); National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, BBC, Al Jazeera, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018