Home | Category: North African Ethnic Groups / North African Minorities

TUAREG SOCIETY AND SLAVES

Tuareg have traditionally lived in a highly-stratified feudal society, with “imaharen “(nobles) and clergy men at the top, vassals, caravaneers, herders and artisans in the middle, and laborers, servants and “iklan” (members of the former slave caste) at the bottom. Feudalism and slavery survive in various forms. Vassals of the imaharen still pay tribute even thought by law they are no longer required to do so. [Source: Carol Beckwith and Angela Fisher, National Geographic, February, 1998; Victor Englebert, National Geographic, April 1974 and November 1965; Stephen Buckley, Washington Post]

Paul Richard wrote in the Washington Post: “Tuareg nobles rule by right. Commanding is their duty, as is guarding family honor — always showing, through their bearing, proper dignity and reserve. Unlike the inadan beneath them, they don't soil themselves with soot, or muck about with blacksmithing, or produce things to use. [Source: Paul Richard, Washington Post, November 4, 2007]

"The blacksmith," observed one Tuareg informant in the 1940s, "is always a born traitor; he's fit to do anything. . . . His mendacity is proverbial; moreover it would be dangerous to offend him, for he is skillful at satire and if need be will spout couplets of his own devising about anyone who brushes him off; thus, no one wishes to risk his taunts. In return for this, no one is as ill-esteemed as the blacksmith."

The Tuaregs live side by side with the black African tribes such as the Bella Some Tuaregs are darker than others, a sign of intermarriage with Arabs and Africans.

“Iklan” are black Africans that often can be found with Tuaregs. "Iklan" means slave in Tamahaq but they are not slaves in the Western sense, Although they are owned and sometimes captured. They are never bought and sold. The Iklan are more like a servant class that have a symbiotic relationship with the Tuareg. Also known as Bellas, they have largely been integrated into the Tuareg tribes, and now are simply seen as inferior beings of a low servant caste rather than slaves.

Tuareg's consider it very rude to complain. They get great pleasure from teasing one another.

Tuaregs are reportedly kind to friends and cruel to enemies. According to one Tuareg proverb you "kiss the hand you cannot severe."

Book: “Wind, Sand and Silence: Travel's With Africa's Last Nomads” by Victor Englebert (Chronicle Books). It covers the Tuareg, the Bororo of Niger, the Danaki of Ethiopia and Djibouti, the Turkana of Kenya.

Websites and Resources: Islam Islam.com islam.com ; Islamic City islamicity.com ; Islam 101 islam101.net ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Religious Tolerance religioustolerance.org/islam ; BBC article bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/islam ; Patheos Library – Islam patheos.com/Library/Islam ; University of Southern California Compendium of Muslim Texts web.archive.org ; Encyclopædia Britannica article on Islam britannica.com ; Islam at Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Islam from UCB Libraries GovPubs web.archive.org ; Muslims: PBS Frontline documentary pbs.org frontline ; Discover Islam dislam.org ;

Islamic History: Islamic History Resources uga.edu/islam/history ; Internet Islamic History Sourcebook fordham.edu/halsall/islam/islamsbook ; Islamic History friesian.com/islam ; Islamic Civilization cyberistan.org ; Muslim Heritage muslimheritage.com ; Brief history of Islam barkati.net ; Chronological history of Islam barkati.net;

Shias, Sufis and Muslim Sects and Schools Divisions in Islam archive.org ; Four Sunni Schools of Thought masud.co.uk ; Wikipedia article on Shia Islam Wikipedia Shafaqna: International Shia News Agency shafaqna.com ; Roshd.org, a Shia Website roshd.org/eng ; The Shiapedia, an online Shia encyclopedia web.archive.org ; shiasource.com ; Imam Al-Khoei Foundation (Twelver) al-khoei.org ; Official Website of Nizari Ismaili (Ismaili) the.ismaili ; Official Website of Alavi Bohra (Ismaili) alavibohra.org ; The Institute of Ismaili Studies (Ismaili) web.archive.org ; Wikipedia article on Sufism Wikipedia ; Sufism in the Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World oxfordislamicstudies.com ; Sufism, Sufis, and Sufi Orders – Sufism's Many Paths islam.uga.edu/Sufism ; Afterhours Sufism Stories inspirationalstories.com/sufism ; Risala Roohi Sharif, translations (English and Urdu) of "The Book of Soul", by Hazrat Sultan Bahu, a 17th century Sufi risala-roohi.tripod.com ; The Spiritual Life in Islam:Sufism thewaytotruth.org/sufism ; Sufism - an Inquiry sufismjournal.org

Tuareg Men and Women

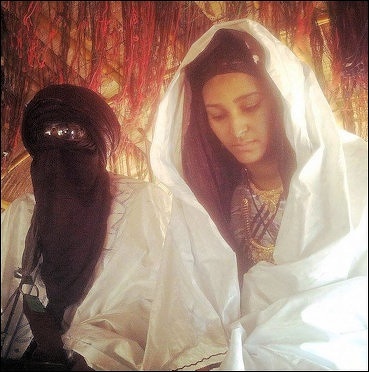

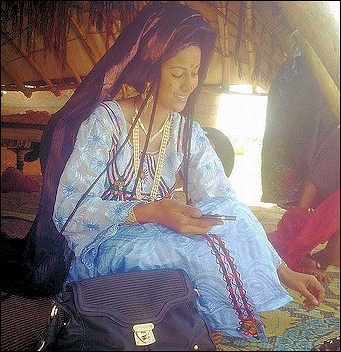

Tuareg woman in Mali

In contrast to other Muslims, Tuareg men not women wear veils. Men traditionally take part in caravans. When a boy reaches three months he is presented with a sword; when a girl reaches the same age her hair is ceremoniously braided. Paul Richard wrote in the Washington Post: “Most Tuareg men are lean. Their movements, by intent, suggest both elegance and arrogance. Their leanness isn't seen as much as it's suggested by the way their loose and flowing robes move about their limbs.

Tuareg women can marry who they please and inherit property. They are regarded as tough, independent, open and friendly. Women traditionally gave birth in their tents. Some women give birth by themselves alone in the desert. Tuareg men reportedly like their women fat.

Women are held in high esteem. They play musical instruments, keep part of the family’s wealth in their jewelry, are consulted on important maters, take care of the household and make decisions while their husbands were on cattle raids or caravans. As for chores, women pound millet, take care of the children and tend sheep and goats. Girls begin taking care of the family's goats and sheep at a relatively young age.

Marriage, Courting and Sniffing

Young Tuareg men have traditionally courted women at evening songfests and unmarried women went weddings in search of prospective husbands. If a couple decides they want to get married, the groom's family must preset camels or cattle to the bride's family, who in turn offer gifts like bowls, saddlebags collapsible beds and palm mats. Child and cousin marriages have traditionally been common. Only a few decades ago, Europeans bought 12-year-old Tuareg brides for $200.

Instead of kissing, Tuareg men and women sniff their noses together. For their part, the Tuareg are appalled that foreigners press their lips together. When couples are dating, it is customary for a young man to sneak into the tent of his girlfriend in the middle of the night and sniff and pet with her and sneak out before dawn. Suitors that are caught by girl’s father sometimes get severe beatings.

Tuareg groom and bride in Niger

National Geographic described two cousins who got married. The groom spotted his future bride drawing water from a well. Even though he had been working in Libya and hadn’t seen his cousin for years, he realized he wanted to marry her and asked her right on the spot. She accepted and once the they received approval of their families they made plans for the wedding.

After the wedding newlyweds move to the camps of the bride’s parents and spend their first year of marriage living with her family. The husband works hard to earn her parents respect and approval. Once this is achieved, the husband can then take his bride to his camp.

Tuareg Wedding

Most Tuareg weddings are held from July to September when caravans have finished their expeditions and rains bring the desert to life. The brides are often 14 or 15 years old, while men are in their mid-20s. The wedding celebration, which usually lasts for several days, includes camel racing, singing, comedy skits and a feasts of roasted meats, dates and rice in a group of tents set up in the middle of the desert.

During a Tuareg wedding, the bride is dressed up in an elaborate costume and gets on a donkey loaded with carpets and pillows and other gifts. The bride travels with a small caravan of family members dressed in their finest clothes across the desert to the groom’s camp. In accordance with Tuareg tradition, marabaouts perform a marriage rite in a local mosque attended by the parents but not the bride and groom.

Before the wedding the bride is attended by female relatives who braid her hair. Then a caste of blacksmiths, believed to possess magical powers, rub fragrant black sand through her hair. During the week-long ceremony she must stay in a tent and is not allowed to speak to anyone except her husband, best friend, mother and attendants.

Tuareg bride

The groom has henna applied to his feet and hands as symbol of purity and fertility as well protection from “jinn”. While surrounded by male friends, the groom has mud-like applied to his feet are wrapped in plastic and palm fronds by female attendants called “tchinaden”. When the covering is removed after two or three hours, the groom’s feet are bright reddish brown.

Describing a high moment of a Tuareg wedding, Carol Beckwith and Angela Fisher wrote in National Geographic: "Ululating and drum beating announces the marriage to arriving guests. Draped in incense-fused robes, female guests add last minute touches of beauty—a red powder called “ewakel”.”

Both the bride and groom are never left alone out of fear that jealous spirits will harm them. Each night the couple spends the night together but the husband leaves before sunrise each morning. The bride remains secluded in the tent. After getting married the husband and wife are supposed to avoid their in-laws.

The newlyweds sleep in an “ehan”, a nuptial tent, taken apart and dissembled each day of the wedding festival and made larger each day to symbolize the expansion of the festivities and the marriage itself. The tent is made with a frame of bent polies and covered with planks and palm from mats.

Tuareg Tents and Nomadic Life

Tuareg families live in goatskin tents adorned with tassels. They sit around on leather cushions and sleep on low beds made of tamarisk wood that can be folded up for traveling. Other household items include palm mats (used to cool the tent), bowls and saddlebags.

Tuareg temt

The possessions of a typical Tuareg nomadic family include a bag of grain, some tea and sugar, 5 donkeys, 25 sheep, 4 goats, a kettle, some tea glass, a flashlight, camel-hide tents, goat-skin water bags, torn clothes, a few metal bowls, wooden spoons, leather pillows, straw mats, a small charcoal burner, and little else. Camels are too expensive these days for most Tuaregs.

A Tuareg clan of nine families usually camp in one area for a few weeks or a month and then move a few kilometers within their tribal area to fresh pastures. Tuareg families set up their tents within a few hundred meters of other family tents with in-laws or relatives. The family groups travel together, share grain, watch each other's animals and pool their resources during droughts and hard times.

Nomad chores include taking the animals to the wells to drink and directing them towards grazing lands and making sure they don’t wander away. When they do run off it can take much of the day to find them and guide them back.

See Nomadic Life Under Mongols and Horsemen NOMAD LIFE factsanddetails.com ,NOMAD MIGRATIONS factsanddetails.com , NOMADS IN THE MODERN WORLD factsanddetails.com .

Tuareg Everyday Life

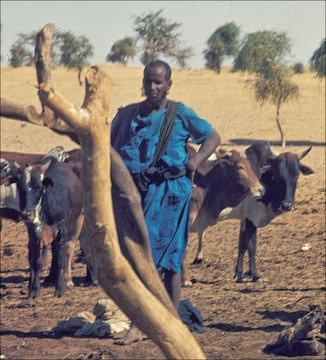

Tuareg in Mali in 1974

Daily activities in the old days including picking lice out of each other's hair, collecting firewood and water, and grooming each hair. Nothing makes a Tuareg nomad happier than sitting around a campfire drinking tea. Donkeys are used for transporting women and carrying goatskin waterbags. Aches and pains for both people and animals are soothed with tobacco spit. People only go to the government hospitals as a last resort. Their only education for along time was memorizing passages from the Qur’an.

The Tuaregs endure 120̊F heat, skin-scouring sandstorms and droughts that leave behind trails of camel, donkey and human bones. Berbers and Tuaregs take few showers. Tuaregs rarely wash in the desert, where water is only for drinking. They brush their teeth with a twig from a special plant.

Tuaregs sing love ballads and historical songs, accompanied by handclaps, beats from drums made of goastskin stretched over a mortar and melodies from leather-cover calabashes strung with horsehair and played with a bow. With servants doing many of their chores, Tuareg women occupy their time by making leather cushions with colorful pasterns Tuareg feet are so tough and calloused from years of walking barefoot on to desert sand, the y can place they feat in campfires without feeling pain or suffering an ill effects. Tuareg are also very adept at picking objects with their feet and their fitst two to are strong from using them to gue camels,

Tuareg Food, Drink and Animals

The Tuareg staple is watery millet and goat cheese gruel. They also consumer dates, camel and goat milk, goat cheese, rancid butter, sorgum. “fonio” and “cramcram”, wild grasses with nutritional grains. Food is usually eaten from a common bowl, with everyone serving themselves with a wooden spoon. If someone doesn’t have a spoon, another person will share his.

Tuareg bread

Herd of animals are usually raised for milk and prestige. They are generally only butchered for feasts or barter. Goats supply milk and cheese. Slabs of beef are hung in trees to dry out for sale in Nigeria.

The Tuaregs like their tea sticky sweet. It is prepared with great care and ceremony and each person drinks three small glasses. The water consumed by caravans is often very salty and has mud, camel and goat hair and leaves floating around in it. Many people get dysentery from drinking it.

Tuaregs keep camels and goats in the Sahara Desert and cattle and sheep in the Sahel. Donkeys are like poor man’s camels. They are used as beasts of burden but they can’t carry as much and are more vulnerable to the desert than camels. Sheepskin is used for blanket-like coverings. Wool is often sold or bartered. One Tuareg nomad told the Washington Post," The animals are my life. if they die, we die." Animals that are severely sick have their throats slit and are buried.

Tuareg Male Veils and Clothing

Both Tuareg men and women wear indigo scarves. Women sometimes go topless. The silver Tuareg cross is distinctive . For day to day use, men wear baggy shirts and ankle-length pants. When in town they don their indigo “ganduraj” and long desert robes, worn over their other garments. Men also like to wear dark sunglasses.

The Tuareg dye many of their clothes with indigo which is traditionally pounded rather than soaked in because of the shortage of water. When temperatures rise indigo wears off on the wearer. Often it looks like they have bluish grease all over them.

tagilmust

When in the desert or as a show of their identity, Tuareg men wrap their face and head in a 20-foot-long veil-turban called a “tagilmust” (tagelmoust, tagelmust), which covers their entire face except for the eyes and sometimes the nose. The Nigerian-made fabric is dyed with indigo, which rubs off on the wearer’s skin, earning the Tuareg the nickname "the blue men of the desert."

Tagilmusts were originally worn to protect the head from sun and sand. But now the are often worn when ever the men are in public, almost like Muslim women wearing the veil. They are worn as a sign of respect to other men and to keep out evil spirits called “jinn”. Every man reportedly has his own style for tying his tagilmsust. Tagilmusts are similar to veils worn by women in Fano, Denmark. These women wear a hat with a mask that covers the lower half of the face and protects it against sand whipped up dunes in the area.

As is true with Sikhs and their turbans, one must know a Tuareg male very well be able to see him without his tagilmust. Strict practitioners reveal only their eyes, passing food under the garment to their mouth when they eat. As times passes more or more Tuareg men are adopting modern ways and abandoning the tagilmusts. Tuareg chiefs traditionally wore tagilmust and a “tcherot”, a brass headband inscribed with Qur’anic verses, to keep the turban in place.

Tuareg Art

In a review of an exhibition of Tuareg art at the National Museum of African Art in Washington D.C. in 2007, Paul Richard wrote in the Washington Post: “Their tent poles look like the standards borne by the Roman legions. The patterns of their amulets have antecedents in Carthage. The Cross of Agadez, the chief emblem of the Tuareg, appears to be descended from the ankh of ancient Egypt. There are marks on Tuareg bracelets that are identical to those seen in Libyan inscriptions of the 2nd century B.C.

traditional Tuareg arms

“The thoughtful exhibition is far too self-aware to indulge in overcooked stereotypical Orientalism. But its leather bags and hand-forged swords, its camel saddles and sugar shears, share this with the ripe paintings of Delacroix and Matisse. Both intentionally conflate, as does most of Tuareg art, the wholly up-to-date with the very old indeed.

“Much that's on display, the luxury goods especially (the Hermes of Paris bags and the Hermes of Paris scarves, the salt shakers and chopstick rests), is self-evidently new -- though the Tuareg decoration that embellishes such objects often feels, instead, biblically antique. Grouped triangles, for instance, repeatedly appear in Tuareg decoration. Standing side by side, those equilateral triangles distantly recall the Pyramids of Giza.

Tuareg Art, the French and Judaism

Paul Richard wrote in the Washington Post: All in all, the Tuareg don't look much like Parisians. When 19th-century French imperialists first came upon the Tuareg in the wastes of the Sahara, they reacted as they might have when meeting men from Mars. [Source: Paul Richard, Washington Post, November 4, 2007]

“The Tuareg were, to French eyes, menacing, imposing, alien and exotic. Their beauty was undeniable, as was their ferocity (it took more than 20 years before imperialist French armies felt confident in entering traditional Tuareg lands), as was their ability to navigate the desert. The Tuareg didn't just raid French colonialists. They raided each other. Sometimes 20,000 camels would be gathered for the long and risky Tuareg-guarded caravans that carried loads of salt south to Timbuktu.”

“It is still easy to see why the beauty of the Tuareg, and other desert peoples, sent a shiver through French art, tinting with strange hues the otherworldly Orientalism of painters as diverse as Eugene Delacroix, Jean-Leon Gerome and Henri Matisse. Judaism, too, has a place in Tuareg art, almost all of which is made by a people called the inadan -- an admired and despised class of Tuareg artisans (and diplomats, censors, clowns and spies) who believe themselves related to the House of David, and are thought to be descended from enslaved Moroccan Jews.”

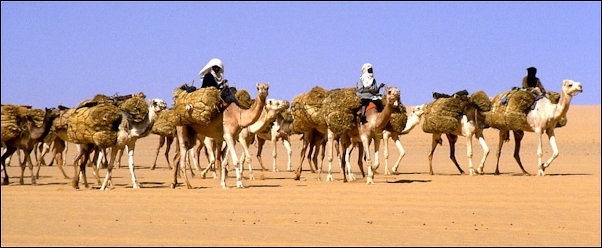

Tuareg Bilma-Agadez Caravan

salt that was carried on the Bilma-Agadez Caravan

In 1965 Belgian anthropologist Victor Englebert accompanied a Tuareg caravan on a 600-kilometers journey from the salt pits of Bilma in the heart of the Sahara in eastern Niger to Agadez, a Nigerien town on the threshold of the Sahara and the Sahel. Once caravans with 30,000 camels traversed this route but by the 1970s the handful of caravans that remained had only a few hundred animals. The salt caravans remained profitable because the transportation cost of bringing salt from the sea or an African port was prohibitively expensive. There was biannual 3,000-camel caravan that ran between Timbuktu and the salt mines of Taoudenni in northern Mali that was operating until relatively recently. It may still be going. [Source: "The Essence of Life: Salt" by Gordon Young, National Geographic, September 1977]

The caravan worked its way across the desert from one brackish well to the next, navigating its way through the relatively featureless desert using the sun, wind, stars, the configuration of the dunes and a handful of key landmarks. Millet was carried along for food and water was sipped sparingly. Many Tuareg walked through the scorching, energy-draining soft sand with callus-covered bare feet. The caravaneers walked beside their animals and only mounted the animals if they become too tired to walk. Saddle camels, mounted by riders, were controlled with the feet of a driver and a single rope attached to the camel’s's nostrils.

Drums were used to signal people it was time to load up the camels and donkeys. Once it started up for the day, the caravan didn't stop sometimes until late at night, moving steadily along at between 1½ and 2½ miles per hour. The caravaneers ate and drank their lunch while they were walking. Stopping or hesitating threw the camels out of rhythm, causing some to kneel and pitch their loads over their backs.

The Bilma-Agadez Salt Caravan began in the dry, relatively mild winter season in Bilma, in an area of the Sahara once covered by an inland sea, where members of the Kanuri tribe pour water in salt pits and add natron (sodium carbonate) to remove impurities. The mixture is then poured in wooden molds that produce mushroom-shaped blocks of salt that weigh around 18 kilograms. It is not clear why a mushroom shape was selected for the mold, especially when considering that such blocks are difficult to fit onto camel and they often break, thus losing part of their value. Unbroken block are sold in the markets for ten times the price that was paid in Bilma

From Bilma the caravans travels for about a week to Fachi, where there is an oasis with a good supply of water and plenty of grass for the camels. The caravan usually stopped here for a couple of days. From Fachil the caravan headed east for another week to the Tree of Ténéré, a single acacia tree that stands alone in the desert hundreds of kilometers from another tree, marking the location of well. After Ténéré, the going gets easier: It is only a three day walk to the next well in Tazolé and the caravaneers only fill their goatskins halfway. From Tazolé it is a five day walk to Agadez with plenty of water and grass along the way. Agadez is accessible to the markets in Mardi and Kano.

Bilma salt caravan

Life on the Tuareg Bilma-Agadez Caravan

The camels on the Tuareg Bilma-Agadez caravan roped together tail to nose. Each animal carried around six of the 18-kilogram blocks of salt, which were wrapped in straw matting, balanced and tried to the camel’s packs with palm-fiber ropes. When the caravan stopped for night, everything was unloaded, and the camels were hobbled to keep them from wandering too far. Caravaneers are exempted from participating in the Ramadan fast when traveling on a caravan.

At night a camp was set up and men drank tea and went straight to sleep or sat around and told stories, depending on how exhausted they were. The caravan tried to stop some at place with grass for the camels to eat. If grass was found, the camels grazed all night and gathering them together again sometimes took up the entire morning. Locating strays could take an entire day. When no grass was available, fodder was unloaded from the packs.

The Tuaregs marched right through the mid-day heat, sipping only occasionally from their goatskin canteens. They liked to sing songs about love and battles when they were walking. They usually didn't wear their veils unless they were approaching a camp with other people. If a rare winter sandstorm kicked up, the caravaneers hid behind walls of mats and let the camels go to fend for themselves. When no wells were available the caravaneers sometimes dug holes in wadis (dry stream beds), where there was usually water as well as grass for the camels,

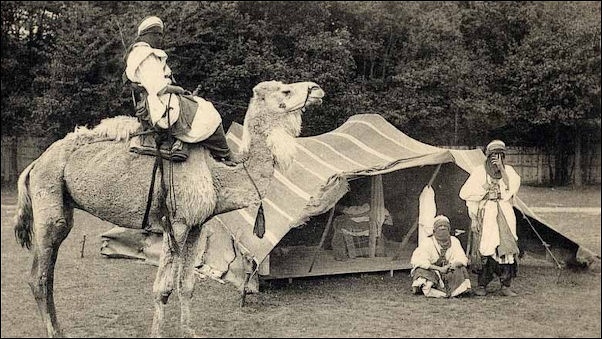

Tuareg in 1907

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994). “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, BBC, Al Jazeera, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018