Home | Category: North African Ethnic Groups / North African Minorities

BERBERS

Chleuh (a Berber Group) dance

Berbers are the indigenous people of Morocco and Algeria and to a lesser extent Libya and Tunisia. They are descendants of an ancient race that has inhabited Morocco and much of northen Africa since Neolithic times. The origins of the Berbers are unclear; a number of waves of people, some from Western Europe, some from sub-Saharan Africa, and others from Northeast Africa, eventually settled in North Africa and made up its indigenous population.

Berber is a foreign word. The Berbers call themselves Imazighen (men of the land). Their languages is totally unlike Arabic, the national language of Morocco and Algeria. One reason the Jews have prospered in Morocco is that has been a place where Berbers and Arabs shaped the history and multi-culturalism has been a fixture of everyday life for a long time.

The origins of the Berbers are unclear; a number of waves of people, some from Western Europe, some from sub-Saharan Africa, and others from Northeast Africa, eventually settled in North Africa and made up its indigenous population. [Source: Helen Chapan Metz, ed. Algeria: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1994 *]

The Arabs have traditionally been townspeople while the Berbers lives in the mountains and desert. The Berbers have traditionally been dominated politically by the Arab ruling class and population majority but many Moroccan believe the Berbers are what gives the country its character. "Morocco “is” Berber, the roots and the leaves," Mahjoubi Aherdan, longtime leader of the Berber party, told National Geographic.

Websites and Resources: Islam Islam.com islam.com ; Islamic City islamicity.com ; Islam 101 islam101.net ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Religious Tolerance religioustolerance.org/islam ; BBC article bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/islam ; Patheos Library – Islam patheos.com/Library/Islam ; University of Southern California Compendium of Muslim Texts web.archive.org ; Encyclopædia Britannica article on Islam britannica.com ; Islam at Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Islam from UCB Libraries GovPubs web.archive.org ; Muslims: PBS Frontline documentary pbs.org frontline ; Discover Islam dislam.org ;

Islamic History: Islamic History Resources uga.edu/islam/history ; Internet Islamic History Sourcebook fordham.edu/halsall/islam/islamsbook ; Islamic History friesian.com/islam ; Islamic Civilization cyberistan.org ; Muslim Heritage muslimheritage.com ; Brief history of Islam barkati.net ; Chronological history of Islam barkati.net;

Shias, Sufis and Muslim Sects and Schools Divisions in Islam archive.org ; Four Sunni Schools of Thought masud.co.uk ; Wikipedia article on Shia Islam Wikipedia Shafaqna: International Shia News Agency shafaqna.com ; Roshd.org, a Shia Website roshd.org/eng ; The Shiapedia, an online Shia encyclopedia web.archive.org ; shiasource.com ; Imam Al-Khoei Foundation (Twelver) al-khoei.org ; Official Website of Nizari Ismaili (Ismaili) the.ismaili ; Official Website of Alavi Bohra (Ismaili) alavibohra.org ; The Institute of Ismaili Studies (Ismaili) web.archive.org ; Wikipedia article on Sufism Wikipedia ; Sufism in the Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World oxfordislamicstudies.com ; Sufism, Sufis, and Sufi Orders – Sufism's Many Paths islam.uga.edu/Sufism ; Afterhours Sufism Stories inspirationalstories.com/sufism ; Risala Roohi Sharif, translations (English and Urdu) of "The Book of Soul", by Hazrat Sultan Bahu, a 17th century Sufi risala-roohi.tripod.com ; The Spiritual Life in Islam:Sufism thewaytotruth.org/sufism ; Sufism - an Inquiry sufismjournal.org

Berber Groups

The major Berber groups in Algeria are the Kabyles of the Kabylie Mountains east of Algiers and the Chaouia of the Aurès range south of Constantine. Smaller groups include the Mzab of the northern Sahara region and the Tuareg of the southern Ahaggar highlands, both of which have clearly definable characteristics. The Berber peasantry can also be found in the Atlas Mountains close to Blida, and on the massifs of Dahra and Ouarsenis on either side of the Chelif River valley. Altogether, the Berbers constitute about 20 percent of the population. [Source: Helen Chapan Metz, ed. Algeria: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1994 *]

Mzab valley

By far the largest of the Berber-speaking groups, the Kabyles, do not refer to themselves as Berbers but as Imazighen or, in the singular, as Amazigh, which means noble or free men. Some traces of the original blue-eyed and blond-haired Berbers survive to contrast the people from this region with the darker- skinned Arabic speakers of the plains. The land is poor, and the pressure of a dense and rapidly growing population has forced many to migrate to France or to the coastal cities. Kabyles can be found in every part of the country, but in their new environments they tend to gather and to retain some of their clan solidarity and sense of ethnic identity.*

In the hills north of the Chelif River and in some other parts of the Tell, Berbers live in villages among the sedentary Arabs, not sharply distinguished in their way of life from the Arabic speakers but maintaining their own language and a sense of ethnic identity. In addition, in some oasis towns of the Algerian Sahara, small Berber groups remain unassimilated to Arab culture and retain their own language and some of their cultural differences.*

In Morocco, the Chleuh Berbers of the High Atlas are known for their fierceness, agriculture skills, strict adherence to Islam, thriftiness and internecine fighting. The Ammein division of the Chleuh Berbers is known for is financial acumen.

Kabyles

By far the largest of the Berber-speaking groups, the Kabyles, do not refer to themselves as Berbers but as Imazighen or, in the singular, as Amazigh, which means noble or free men. Some traces of the original blue-eyed and blond-haired Berbers survive to contrast the people from this region with the darker- skinned Arabic speakers of the plains. The land is poor, and the pressure of a dense and rapidly growing population has forced many to migrate to France or to the coastal cities. Kabyles can be found in every part of the country, but in their new environments they tend to gather and to retain some of their clan solidarity and sense of ethnic identity. [Source: Helen Chapan Metz, ed. Algeria: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1994 *]

Kabyle villages, built on the crests of hills, are close- knit, independent, social and political units composed of a number of extended patrilineal kin groups. Traditionally, local government consisted of a jamaa (village council), which included all adult males and legislated according to local custom and law. Efforts to modify this democratic system were only partially successful, and the jamaa has continued to function alongside the civil administration. The majority of Berber mountain peasants hold their land as mulk, or private property, in contrast to those of the valleys and oases where the tribe retains certain rights over land controlled by its members.*

Christian Kabyle family

Set apart by their habitat, language, and well-organized village and social life, Kabyles have a highly developed sense of independence and group solidarity. They have generally opposed incursions of Arabs and Europeans into their region, and much of the resistance activity during the War of Independence was concentrated in the Kabylie. Major Kabyle uprisings took place against the French in 1871, 1876, and 1882; the Chaouia rebelled in 1879.*

Chaouia and Mzab

Perhaps half as numerous as the Kabyles and less densely settled, the Chaouia have occupied the rugged Aurès Mountains of eastern Algeria since their retreat to that region from Tunisia during the Arab invasions of the Middle Ages. In the north they are settled agriculturalists, growing grain in the uplands and fruit trees in the valleys. In the arid south, with its date-palm oases, they are seminomadic, shepherding flocks to the high plains during the summer. The distinction between the two groups is limited, however, because the farmers of the north are also drovers, and the seminomads of the south maintain plots of land. [Source: Helen Chapan Metz, ed. Algeria: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1994 *]

In the past, the Chaouia lived in isolation broken only by visits of Kabyle peddlers and Saharan camel raisers, and relatively few learned to speak either French or Arabic. Like their society, their economy was self-sufficient and closed. Emigration was limited, but during the War of Independence the region was a stronghold of anti-French sentiment, and more than one-half of the population was removed to concentration camps. During the postindependence era, the ancient Chaouia isolation has lessened.*

Far less numerous than their northern Berber kin are the Mzab, whose number was estimated at 100,000 in the mid-1980s. They live beside the Oued Mzab, from which comes their name. Ghardaïa was their largest and most important oasis community. The Mzab are Ibadi Muslims who practice a puritanical form of Islam that emphasizes asceticism, literacy for men and women, and social egalitarianism.*

The Mzab used to be important in trans-Saharan trade but now have moved into other occupations. Some of their members have moved to the cities, where in Algiers, for example, they dominate the grocery and butchery business. They have also extended their commerce south to sub-Saharan Africa, where they and other tribal people trade with cash and letters of exchange, make loans on the harvest, and sell on credit.*

Berber Marriage, Weddings and Divorce

Berber wedding

Berbers have traditionally been monogamous. They maintained these customs after the arrival of Islam. Marriages in Berber villages have traditionally been arranged by families in the best interest of the community. The only problem with this system is that the marriages often didn’t work out and the couple got divorced.

Women can not be forced marry someone they don’t like. Even so they are forbidden from marrying against their farthers’ wishes unless a judge gives them permission to do so. Ait Hadiddou women are free to get divorced as many times as they like and remarry whomever they want. The Imilchil bride fair is filled with divorced and widowed women, identified by pointed headdresses.

Berber weddings are private. Staged wedding have been held for tourists in the main square of nearby Agoudal. A traditional ceremony can last for two days and a wedding can last of a week. The main event begins when bride’s’ messenger goes to the house of the groom to pick up presents such as carpets, money and jewelry. Typically she demands more. The bride rides to the ceremony on mule, carrying a lamb, which symbolizes prosperity. behind her is a child which represents fertility. While women ululate men bang of drums the bride is carried to a stage for the ceremony.

Berber Bride Fair

The September moussem of Imilchil in the Atlas Mountains is famous for its three-day bride fair, in which marriageable woman from the region's dominant tribe, the Ait Hadiddou, are displayed and marriageable men from all over Morocco come to check them out. The fair also features music, dancing and camel trading. [Source: Carla Hunt, National Geographic, January 1980]

The Imilchil bride fair is held in a barren open area at the crossroads of dirt tracks around the “marabout” (beehive) tomb of Sidi Muhammad el Merheni, a holy man who lived at some unknown time and was credited with blessing numerous happy marriages. Bachelors appear before the tomb to pray and women grab and pull to be first in front of the tomb for good luck.

The bride fair was set up to find matches for men and women from different tribes and grew out of local legend. According to the story, the event began after a Berber Romeo and Juliet from different tribes were not allowed to marry. They cried so many tears they formed two lakes.

Preparations and Presentations at the Berber Bride Fair

Berber bride by Joseph Tapiro

Villagers bring wool, meat, grain and vegetables to the fair to sell. Sellers set up white tents grouped by product: rugs, pots, tools, ceramics, books. Butchers set themselves up in tents that are some distance from the other tents.

Single women are made up in goat hair tents with carmine rogue streaks on their cheeks, kohl eyeliners and saffrons-colored powder in the eyebrows. They wear poncho-like wool capes striped with tribal colors and keep their pointed headdresses erect on their head with stiffened bones.

Some brides have already chosen their future husbands before the fair and come to the mousseem to formalize their marriage. Other women chose their spouses at the moussem, mulling around in groups near the shrine in their traditional clothes, waiting to choose or be chosen. Westerners have often believed that the men selected the woman but that is not true. Marriages are decided by consent between the bride and groom and their families.

Richard Covington wrote in Smithsonian: Among a clapping crowd packed into a tent “a woman stands up, holding her skirts in one hand and swinging her hips alluringly to the beat. Another woman leaps up, dancing in a mocking, provocative challenge. As the two of them crisscross the floor, the crowd and musicians pick up the pace...The women keep swirling as drummers sizzle. The music reachers a fever pitch, then everyone stops abruptly as if on cue.”

Looking for Brides at the Berber Bride Fair

At the bride fair, white-robbed grooms greet each with hugs and loud welcomes. They generally wander among the brides in pairs and stop and chat, often with their friends’ prodding, to brides that catch their fancy. Sometimes, basing their decision on little more than the woman's eyes and the sound of her voice, a man selects his future wife with a handshake that conveys his wish to marry her.

Berber bachelors who are soon to be wed wear white turbans with a square piece of cloth hanging behind. They sometimes arrive on the back of donkey with s suitcase filled with their other wedding clothes.

Prospective grooms walk from the group holding hands. Often the bribe is accompanied by male relatives who lend advice and offer opinions. If the bride decides she doesn't want to go through with the marriages she lets go of her suitors hand. If the bride agrees to the marriage she says, "You have captured my liver" (Berber believe that true love aids digestion and brings good health).

Choosing a Bride at the Berber Bride Fair

Berber women at Imichil

Villagers bring wool, meat, grain and vegetables to the fair to sell. Sellers set up white tents grouped by product: rugs, pots, tools, ceramics, books. Butchers set themselves up in tents that are some distance from the other tents.

Single women are made up in goat hair tents with carmine rogue streaks on their cheeks, kohl eyeliners and saffrons-colored powder in the eyebrows. They wear poncho-like wool capes striped with tribal colors and keep their pointed headdresses erect on their head with stiffened bones.

Some brides have already chosen their future husbands before the fair and come to the mousseem to formalize their marriage. Other women chose their spouses at the moussem, mulling around in groups near the shrine in their traditional clothes, waiting to choose or be chosen. Westerners have often believed that the men selected the woman but that is not true. Marriages are decided by consent between the bride and groom and their families.

Richard Covington wrote in Smithsonian: Among a clapping crowd packed into a tent “a woman stands up, holding her skirts in one hand and swinging her hips alluringly to the beat. Another woman leaps up, dancing in a mocking, provocative challenge. As the two of them crisscross the floor, the crowd and musicians pick up the pace...The women keep swirling as drummers sizzle. The music reachers a fever pitch, then everyone stops abruptly as if on cue.”

Looking for Brides at the Berber Bride Fair

At the bride fair, white-robbed grooms greet each with hugs and loud welcomes. They generally wander among the brides in pairs and stop and chat, often with their friends’ prodding, to brides that catch their fancy. Sometimes, basing their decision on little more than the woman's eyes and the sound of her voice, a man selects his future wife with a handshake that conveys his wish to marry her.

Berber bachelors who are soon to be wed wear white turbans with a square piece of cloth hanging behind. They sometimes arrive on the back of donkey with s suitcase filled with their other wedding clothes.

Prospective grooms walk from the group holding hands. Often the bribe is accompanied by male relatives who lend advice and offer opinions. If the bride decides she doesn't want to go through with the marriages she lets go of her suitors hand. If the bride agrees to the marriage she says, "You have captured my liver" (Berber believe that true love aids digestion and brings good health).

Choosing a Bride at the Berber Bride Fair

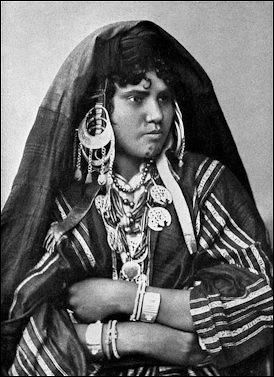

Berber woman in 1904

The prospective bride and groom then wait in a line to enter the wedding tent. After filling out a marriage application in Arabic with the help of an official scribe they enter the tent to meet with a qadi, a representative of the Ministry of Justice Rabat, who asks the couple a few questions before giving his approval to the marriage. Not all marriages are approved. If the bride is in her early teens, for example, the marriage is often rejected.

In the 1970s, the fair was popular with engaged couples because the fee for a marriage contract was $12 as opposed to the normal $50. Inside one tent couples waited in line to sign their marriage contracts in front a panels of officials. When the marriage contract was approved, the groom paid the fee and gave the bride about three times that amount. First time brides leave the fair with their fathers and make arrangement to give the bride away at a feast later on. Newlyweds, divorces and widows go directly to their husbands’ villages to live with them.

One anthropologist told National Geographic, "Marriage by mutual consent and divorce when there is disharmony are central to the social system enveloped by the Ait Hadiddou. Despite their reputation for being fierce and warlike, they have evolved “paix chez eux”, peace at home. Often snowbound behind village walls for six months a year, families must live in harmony.

Berber Women

Berber women traditionally exposed their faces and often sported mysterious blue tattoos on their chins, forehead and cheeks while Arab women went veiled with only their henna-tattooed hands exposed.

Berber village in the Atlas mountains

Within the confines of the traditional system, there was considerable variation in the treatment of women. In Arab tribes, women could inherit property; in Berber tribes, they could not. In Berber society, Kabyle women seem to have been the most restricted. A husband could not only divorce his wife by repudiation, but he could also forbid her remarriage. Chaouia women fared much better because they were allowed to choose their own husbands. [Source: Helen Chapan Metz, ed. Algeria: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1994 *]

On the frustration of young Berber women in post-Gaddafi Libya, Glen Johnson wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “In a local college, teenage boys and girls walk apart, or sit segregated in the school's cafe. An aura of surveillance hangs heavy over cautious demeanors. "There is a tension in the air. It is part of a bigger problem: No one understands each other," says Soltan Tweini, dean of the college. "We need to recognize the diversity in Libyan society and encourage this; no one should force any ideas on other people." [Source: Glen Johnson, Los Angeles Times, March 22, 2012 \=]

“Yet for Zuhair, the mix of religion and tradition is an oppressive force as she and a small group of friends look more to Europe and the United States for identity. She gives the example of some teenage girls who began listening to Western heavy metal and "emo" music two years ago. They were accused of witchcraft, and when pressure was exerted to have them removed from school, they began to dress more modestly. She talks of women who have lost their virginity before marriage sneaking across to Tunisia for hymen reconstructive surgery. In Libya, if a woman has sex outside marriage, she is a nonperson. She laments tradition dictating that she can marry only an Amazigh man, preferably from Zuwarah. That she cannot walk along Zuwarah's long beaches without a relative present. That there are no women's associations in the town.” \=\

In post-Gaddfi Libya the austere Salafi strand of Islam is making it presence known, iand challenging more moderate forms of Islam. Waleed Muhammad, a Salafi adherent, told the Los Angeles Times: "People are free to do as they like, as long as they do not go outside from Islam. The woman's role is to take care of the house but it is not wrong for her to work, as long as this does not affect the house. She can communicate with men, but not outside of what her work requires." [Source: Glen Johnson, Los Angeles Times, March 22, 2012]

Berber Villages and Homes

Tadjine with couscous

Within the confines of the traditional system, there was considerable variation in the treatment of women. In Arab tribes, women could inherit property; in Berber tribes, they could not. In Berber society, Kabyle women seem to have been the most restricted. A husband could not only divorce his wife by repudiation, but he could also forbid her remarriage. Chaouia women fared much better because they were allowed to choose their own husbands. [Source: Helen Chapan Metz, ed. Algeria: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1994 *]

On the frustration of young Berber women in post-Gaddafi Libya, Glen Johnson wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “In a local college, teenage boys and girls walk apart, or sit segregated in the school's cafe. An aura of surveillance hangs heavy over cautious demeanors. "There is a tension in the air. It is part of a bigger problem: No one understands each other," says Soltan Tweini, dean of the college. "We need to recognize the diversity in Libyan society and encourage this; no one should force any ideas on other people." [Source: Glen Johnson, Los Angeles Times, March 22, 2012 \=]

“Yet for Zuhair, the mix of religion and tradition is an oppressive force as she and a small group of friends look more to Europe and the United States for identity. She gives the example of some teenage girls who began listening to Western heavy metal and "emo" music two years ago. They were accused of witchcraft, and when pressure was exerted to have them removed from school, they began to dress more modestly. She talks of women who have lost their virginity before marriage sneaking across to Tunisia for hymen reconstructive surgery. In Libya, if a woman has sex outside marriage, she is a nonperson. She laments tradition dictating that she can marry only an Amazigh man, preferably from Zuwarah. That she cannot walk along Zuwarah's long beaches without a relative present. That there are no women's associations in the town.” \=\

In post-Gaddfi Libya the austere Salafi strand of Islam is making it presence known, iand challenging more moderate forms of Islam. Waleed Muhammad, a Salafi adherent, told the Los Angeles Times: "People are free to do as they like, as long as they do not go outside from Islam. The woman's role is to take care of the house but it is not wrong for her to work, as long as this does not affect the house. She can communicate with men, but not outside of what her work requires." [Source: Glen Johnson, Los Angeles Times, March 22, 2012]

Berber Villages and Homes

The typical Kabyle villages in the Aurès Mountains and the Atlas around Blida were always built above cultivated lands, on or close to mountain tops. They were enclosed by walls with doors that opened inward. The slopes were often terraced to allow the Kabyles to cultivate olive and fruit orchards and to grow wheat and barley. The animals kept by the Kabyles grazed on the vegetation that grew on rocky slopes unsuitable for agriculture. [Source: Helen Chapan Metz, ed. Algeria: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1994 *]

Bedouin introduced the tent to the northern Sahara. Berber nomads live in tents like those by Bedouins. Berber tents have been traditionally made from goat hair.

During the winter, some Berbers are snowbound in their mountain villages. In the spring and summer men have traditionally tended their flocks in upland pastures and women stay close to their villages tending crops, weaving rugs and guarding granaries. According to a Berber proverb, "A woman is the ridge pole of the tent. "

Berber Food

Moroccan Dishes include “tajines” (stews made of almost anything, slowly cooked over a charcoal brazier and served piping hot in a terra-cotta pot with a cone-shaped cover). A typical tajine has a red sauce stew and is made with meat—usually lamb, mutton or chicken, but also beef, pigeon, fish, turkey, camel, quail or duck—and stewed fruit or vegetables—such as potatoes, apples, carrots, artichokes, prunes, grapes, and carrots—and seasoned with olives, hot peppers, tomatoes and spices such as cumin, saffron or mint. There are many kinds of tajines. Popular ones include lamb with prunes; beef with apples; lamb and quince; chicken with grapes, raisins and almonds; duck with figs

Couscous is as much of a fixture of Moroccan cooking as rice is to Chinese cooking and may have arrived in North Africa from the Romans. It is not a grain but rather is very small pasta made from hard, wheat semolina and can be as coarsely textured as peppercorns or as fine as table salt. Steamed and cooked with chunks of lamb, vegetables and sometimes raisins and cinnamon, it is often heaped on a plate with a hollow in the middle and is filled with a stew of chicken or lamb, and garnished with raisins, chick peas or onions. Couscous is often served with a boiled vegetables or soup and a bowl of hot pepper sauce.

Among the popular pastry-style dishes are “brewat” (deep-fried pastry with spiced meat, rice and almonds inside), “pastilla” (flaky pastry filled with chicken or pigeon and almonds, cinnamon, eggs, sugar, onions, ginger, coriander and saffron), “bisteeya” (flaky pastry filled with spiced pigeon, toasted almonds, onion sauce and lemony eggs and covered with powdered with cinnamon and sugar) and “rghaifs” (stuffed fried pancakes);

Other typical Moroccan dishes include “harira” (a thick chicken soup, often with chickpeas, eggs and flavored with pepper, saffron and cinnamon), “brouchettes” (skewered chunks of barbecued mutton, lamb, beef or chicken), “meschoui” (roast mutton), “djaja mahamaru” (chicken stiffed with almonds, raisins and semolina), “merguez” (spiced lamb sausages), chicken with lemon and olives.

Berbers like to drink mint tea. Common vegetables and nuts include cabbage, vine leaves, olives, cucumbers, sweet peppers, hot peppers, garlic and eggplant. Common fruits and nuts include dates, grapes, oranges, Arab-style, brine-preserved lemons, bananas, apricots, figs, melons, apples, pistachios, and almonds. Fruit is often served at the end of meals.

Berber Clothes

Outside the cities, Berbers are often easy to distinguish by their dress. Men wear thick, hooded robes. When is rainy, they pull up their pointed hoods and look like gnomes. The material used for these robes is thick and hides smells. Stripes are very popular among the Berbers especially on their robes. Each pattern is unique to a certain tribe or clan. Berbers in the Rif mountains and eastern Morocco often dress completely in white. Some horsemen even ride white horses. Berbers in the desert sometimes wear skullcaps with unique designs of their clan.

Berber women are famous for their embroidered wool and cotton izars (loose-fitting, body-covering tunic worn by Muslim women),and hendiras. (small wool blankets worn as an overcoat). Izars are similar to ancient Greek chitons and Roman peplos. They are generally comprised of a 4½-meter-by-1½ meter piece of cloth held at the waist by a belt and supported at the shoulders by fibulas. The decorative patterns and the way the hendira is worn varies from one tribe to another.

Berber women have traditionally not covered their faces. They wear a variety of head coverings including straw hats and fringed scarves knotted at the back. In the south some women wear a colored scarf tied to a brocaded cap with coins dangling over the forehead. Some woman wear a veil that reveals only their eyes .

Berber Women’s Jewelry

Berber women often carry their family's wealth in their jewelry. They are often covered in sequins, silver jewelry, amber beads and headdress with dangling coins. Necklaces strung with silver and big chunks of amber are greatly prized. Tattoos, headdresses, jewelry, belts and shoes show great variety from one region to another.

Handmade silver jewelry is worn by most women. Many women wear large elaborately-decorated fibula pins studded with stones with long chains hanging from each pin. Large amber beaded necklaces are worn by big events like weddings.

The Ait Hadiddou women of the High Atlas Mountains wear a rounded hood srungwith colorful wool streams, a necklaces with thick amber chunks, and red pink lightning makeup during an annual festival in which eligible men seek wives. Women with peaked hoods are widowed or divorced and "open to instant proposals of marriage without the formalities of parental negotiation and a long engagement."

Berber Arts and Crafts

Morocco is famous for its crafts made from leather, silver, brass, amber and carved wood. Many crafts such as embroidery and brass working are regarded as art forms. There is a worldwide demand for Moroccan mosaics and zillij (tiles). Moroccan crafts reached their peak under the Maranids, who brought styles from Spain. Fez is particularly famous for crafts such as ceramics, zillij. Some designs are inspired by alchemy and ancient ceramics.

Some zillij makers come from families who have been making zillij for six generations. Fez mosiac makers work with 350 different shapes including eight-ponted stars, hexagons and elongated almonds. There are government-run institutes for traditional crafts.

Morocco craftsmen are of both Arab and Berber descent. Souks, or markets, are filled with interesting shops: carpet shops selling hand-woven, embroidered Berber rugs, medicine shops with dried turtles and live chameleons and spice shops displaying large baskets filled with saffron, orange blossoms, sandalwood, bay leaf, thyme, mint leaves, pepper, paprika, and ginger. Southern Morocco is famous for green-glazed pottery from the Draa Valley; Tuareg silver jewelrys; and carpets and henbels (flatwoven rugs) from the Atlas Mountains and the Sahara.

Crafts included embroidered kaftans, blue pottery, silver jewelry with semiprecious stones, brightly painted slippers, fezzes, leather sandals, harem rings, embroidered clothing, gold crafts, inlaid woodwork, various kinds of handmade crafts, cotton and wool textiles, copperware, a wide rang of died leather items, Arabic-style clothes, head scarfs, onyx and meerschaum items, hand painted crafts and jewelry made with amber and agate.

Berber Music

Amazigh (Berber) peoples

Much of the music of Morocco is Berber in origin. Berber music is very different from Arab music. It has different rhythms, tunings, instruments and sounds with the music traditionally having been passed down orally. [Source: Rough Guide to World Music]

There are three main kinds of Berber music: 1) village music: festive dance music traditionally performed with at festivals, weddings and feasts; 2) ritual music: more atmospheric music performed at religious festivals, marriage ceremonies, rainfall and spirit exorcism rituals and often accompanied by flutes, drums and hand clapping; and 3) professional music: performed by traveling minstrel-like poets who sing traditional stories and deliver news accompanied by drums, “rabab”, and “ghatai”,

Professional music is often performed at weekly souks in the Atlas mountains. Rwais are professional musicians who work in the Soussa Valley. They are fairly large groups with a developed repertoire. A performance usually begins with an instrumental prelude followed by a sung poetry and dance pieces climaxing with a finale that builds and builds and abruptly ends.

The “ghaita” is an oboe-style instrument. The “aghanin” is double-reed clarinet known as an “arghul “in the Arab world. Many Moroccan style flutes (“nai”, “talawat”, “nira”, “gasba”) are made from a straight piece of cane, open at both ends, with five to seven finger holes. Moroccan drums include the “bendir” (hand drums); the “taaija”, a pottery drum struck like a tambourine; “tam tam bongies”, played with sticks or hands; the “guedra”, a large drum that resta on the ground, and the “tabl”, a round wooden drum with skins on both sides, used in rural Berber music;.

Stringed instruments include the oud, rabab gimbri and “lotar” (lute-like instrument, used by the Chleuh Berbers, that has a circular body and three or four strings and is plucked with a plectrum). The Moroccan buzuk is similar to the Greek bouzouki. It is usually electric and has anywhere from four to ten strings and is usually tuned in the Western manner.

Chaabi is Moroccan pop music. Among the popular contemporary chaabi performers are Najat Aatabou, a female singer proud of her Berber root and outspoken and social and moral issues; Lem Chaheb, regarded as one of the most Westernized chaabi performers; Muluk el Hwa, a group of Berbers who used to play in the Djemaa al Fna in Marrakesh; Dissidenten, a Berlin-based group that merge Sufi music and rock.

Berber Dances and Fantasias

The most well known Berber dances are the a”houach”, performed in the western High Atlas mountains and the “ahidus”, performed by the Chleuh Berbers in the High Atlas. Men and women in colorful costumes dance to mysterious “guedra” music, accompanied only by “bendirs” (hand drums) and flutes. The dances begin with a chanted prayer in which the dancers chant in unison and form a circle around the musicians. The dances are very complex and often require a great deal of practice and rehearsals to get right. The “ahouach” is a dance normally performed at night in an open square in the kasbah.

“Fantasia”, a traditional form of entertainment intended to simulate a mounted battle, are held to celebrate big occasions such as the wedding of a princess, the circumcision of a prince, the opening of a hospital ro a visit by a foreign VIP. In large fantasias, hundreds of Berber horsemen charge the crowd and reign in their horse at the last moment, firing their long-barreled muskets into the air.

fantasia

Describing a fantasia Thomas Abercrombie wrote: "A dozen turbaned riders, twirling their muzzle-loaders, screamed across the plain full-bore toward us. I looked for a place to jump. But, reigned in hard foaming horses thundered to a stop—seemingly inches away—splashing us with their dust and gunpowder. Before the cloud settled, they galloped off to make room for the next wave hard on their heels. [Source: Thomas Abercrombie, National Geographic, June 1971]

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994). “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, BBC, Al Jazeera, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018