Home | Category: Middle East Ethnic Groups / Middle East Minorities

KURDS

Kurdish men in traditional clothes in Hawraman in eastern Iraq and western Iran

There are over 35 million Kurds, with 12 million in Turkey, 6 million in Iran, about 5 to 6 million in Iraq, and less than 2 million in Syria. They are the largest ethnic group in the Middle East without a country and one of the largest ethnic groups in the world without a homeland-state to call their own. Their homeland is in the rugged mountains where Iran, Turkey, Syria and Iran come together. Over half of all Kurds live in Turkey. Some live in the former Soviet Union. [Sources: Wikipedia, "Struggle of the Kurds" by Christopher Hitchens, National Geographic, August 1992 ♠]

The Kurds were once a nomadic people. Now most of them are farmers, or have migrated to the cities. Most Kurds have dark skin and dark hair, but, like Turks, there are some with blue eyes and fair hair. Their language is not related to Arabic, Persian or Turkish. It is more closely affiliated with European languages. Most Kurds are Sunni Muslims, but there are also many Christian ones, and even some Jewish Kurds.

The Kurds have had the misfortune of living where the Arab, Turkish and Persian civilization all intersect. Throughout their history they have been ruled others: Persians, Arab Caliphs, Seljuk Turks, Mongols, Ottoman sultans, Turkish nationalists, Britain and the countries that occupy Kurdish lands now.

A common theme of Kurdish history has been their inability to create a Kurdish state. One expert on the Kurds told the New York Times that Kurds suffer from “the deep belief that the outside world is always trying to take their country away from them.”

The Kurds have a history of being used as proxies by outside powers and have been kept from unifying by the propensity of rival Kurdish factions to fight among themselves. These factions have often allied themselves with the traditional foreign enemies of the Kurds to fight rival Kurdish factions. In turn, foreign powers have often used the Kurds when it suited their goals and abandoned them without warning. For centuries the Turks denied the existence of Kurds, calling them “mountain Turks.”

Books: “A Modern History of the Kurds” by David McDowell Sheri Laizer, “After Such Knowledge: What Forgiveness, My Encounters in Kurdistan” by Jonathan C. Randal (Farrar, Straus Giroux); “Kurdistan: In the Shadows of History” By Susan Meiselas (Random House, 1998).

Websites and Resources: Islam Islam.com islam.com ; Islamic City islamicity.com ; Islam 101 islam101.net ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Religious Tolerance religioustolerance.org/islam ; BBC article bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/islam ; Patheos Library – Islam patheos.com/Library/Islam ; University of Southern California Compendium of Muslim Texts web.archive.org ; Encyclopædia Britannica article on Islam britannica.com ; Islam at Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Islam from UCB Libraries GovPubs web.archive.org ; Muslims: PBS Frontline documentary pbs.org frontline ; Discover Islam dislam.org ;

Islamic History: Islamic History Resources uga.edu/islam/history ; Internet Islamic History Sourcebook fordham.edu/halsall/islam/islamsbook ; Islamic History friesian.com/islam ; Islamic Civilization cyberistan.org ; Muslim Heritage muslimheritage.com ; Brief history of Islam barkati.net ; Chronological history of Islam barkati.net;

Shias, Sufis and Muslim Sects and Schools Divisions in Islam archive.org ; Four Sunni Schools of Thought masud.co.uk ; Wikipedia article on Shia Islam Wikipedia Shafaqna: International Shia News Agency shafaqna.com ; Roshd.org, a Shia Website roshd.org/eng ; The Shiapedia, an online Shia encyclopedia web.archive.org ; shiasource.com ; Imam Al-Khoei Foundation (Twelver) al-khoei.org ; Official Website of Nizari Ismaili (Ismaili) the.ismaili ; Official Website of Alavi Bohra (Ismaili) alavibohra.org ; The Institute of Ismaili Studies (Ismaili) web.archive.org ; Wikipedia article on Sufism Wikipedia ; Sufism in the Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World oxfordislamicstudies.com ; Sufism, Sufis, and Sufi Orders – Sufism's Many Paths islam.uga.edu/Sufism ; Afterhours Sufism Stories inspirationalstories.com/sufism ; Risala Roohi Sharif, translations (English and Urdu) of "The Book of Soul", by Hazrat Sultan Bahu, a 17th century Sufi risala-roohi.tripod.com ; The Spiritual Life in Islam:Sufism thewaytotruth.org/sufism ; Sufism - an Inquiry sufismjournal.org

Kurdistan

Kurdish inhabited areas in 2002 according to the CIA

Kurdistan (“The Land of the Kurds”) extends for about 960 kilometers from east to west and 190 to 240 kilometers from north to south. Occupying southeastern Turkey, northern Iraq, northeast Syria and southwest Iran, it embraces the eastern Tarsus and Zagros mountains and includes the steppelike plains in the north and the foothills of the Mesopotamian plains to the south. These area have traditionally been very hot in the summer and very cold in the winter, often with heavy snows followed by spring rains and heavy run-off down the slopes. The harsh weather and rugged terrain has traditionally made the region difficult for outsiders to penetrate and control on the region by outsiders has traditionally been tenuous at best.

Kurdistan covers a large area. In addition to Kurds there are also large numbers of Arabs, Turks, and Iranians living there as well as members of minorities such as Yazidis, Mandeans, and Christian sects such as the Nestorians, Armenians, Jacobites and Assyrian Christians.

The Kurdish National Motto, with origins older than anyone can remember is simply: "The Kurds have no friends." Some put it another way and say "Our only friends are the mountains." The mountains have been both a curse and blessing. They have provided them with a refuge but also isolated then from the attention of the outside world.

Kurdish Population

The Kurds are the Middle East’s forth largest ethnic group after Arabs, Iranians and Turks.

By one count there are about 35 million of them, with 28 million in Kurdistan. Kurds make up a significant majority in the places where they live. Their homeland is the rugged mountains where Iran, Turkey, Syria and Iran come together.

About 14.5 million of all Kurds live in Turkey. Of these, around half live in the east and southeast part of the country. Another big chunk live in Ankara, Istanbul and Izmir. The rest are scattered throughout Turkey.

Kurds living outside Turkey include 5 to 6 million in Iraq, 6 million in Iran, less than 2 million in Syria, 750,000 in Germany, 300,000 in Russia and 100,000 in Armenia and 350,000 elsewhere in Europe. A small group of Kurds lives in Israel; across the border in Lebanon they are considered the lowest of the low. Recent emigration has resulted in a Kurdish diaspora of about 1.5 million people, about half of them in Germany. Several thousand Kurds, including many that worked with U.S. troops in northern Iraq, have settled in the United States. Many reside in Fargo, North Dakota, San Diego and Nashville, Tennessee.

Kurdish couples tend to have lots of children and families are big. The population figures are not regarded as accurate because of the political policies towards the Kurds in the countries where Kurds are found.

Kurdish Language

Kurdish is an Indo-European language. It is not related to Arabic or Turkish, but is somewhat related to Persian. There are several dialects of Kurdish. Kurdish dialects are so different they can be considered different languages. Those in northern Iraq, eastern Turkey and the former Soviet Union speak “Kurmanji”, while those in western Turkey speak “Zaza”. In southern Iraq “Sorani” prevails; in Iran the “Guran” and “Laki” dialects are the most common. Soviet Kurds speak the northern dialect (Kurmandz) of the Kurdish language, which belongs (along with Talysh and some other languages) to the Northwestern Subgroup of the Iranian Group of the Indo-European Family.

Kurdish languages: dark green: Kurmanji (Northern Kurdish); olive green: Sorani (Central Kurdish); green: Pehlewani (Southern Kurdish); yellow: Zazaki; orange: Gorani; purple: mixed areas The shaded areas indicate the presence of Kurdish-speaking communities, but not necessarily a local Kurdish majority. The map is based on a 2007 overview map made for Le Monde Diplomatique. Controversially, the map shows Zazaki and Gorani along with Kurdish, and divides Kurdish proper in two groups one "Northern" called Bahdinai (i.e. Bādīnānī, a.k.a. Kurmanji) and "Southern" called Sorani. The Southern group seems to include both the "Central" and the "Southern" dialects in linguistic classification, presumably because "Central" (Sorani) orthography is also used by speakers of Southern dialects. The areal of "Gorani" overlaps significantly with "Southern Kurdish", and Gorani speakers (about 0.3 million) are greatly outnumbered by Southern Kurdish speakers (about 3–4 million), so that the "Gorani" portion of the map may appear exaggerated; in fact, most (but not all) of the Southern Kurdish area is shown as "Gorani" in the map. The edited map shows Kurdish proper in three groups: Kurmanji (Northern Kurdish) Sorani (Central Kurdish), Pehlewani (Southern Kurdish). It also shows Zazaki Gorani (which it now separates from Southern Kurdish)

The Kurdish language was not studied until comparatively late in Europe (the first Kurdish grammar was published in 1787). In 1921 a Kurdish alphabet was devised in Armenia on the basis of the Armenian alphabet. A Kurdish alphabet using Latin letters was created in Armenia in 1929. In 1944, also in Armenia, a Kurdish alphabet using Cyrillic characters (with the addition of seven signs for the rendering of specific phonemes) was promulgated, although this led to some isolation of the Soviet Kurdish readership. (All Kurdish literature abroad is published in the Latin and Arabic alphabets.) [Source: Encyclopedia of World Cultures]

In 1924 in Turkey, Ataturk passed a law restricting the use of the Kurdish language. The law was not lifted until 1991. The Turkish government outlawed the use of the Kurdish language in public and the publication and the possession of anything in the Kurdish language. Today Kurds are allowed to speak Kurdish and have Kurdish newspapers, but they can't use the language in school or in advertisements on television. Nor can they give their children Kurdish names. European diplomats believe that the tension between the Kurds and Turkey would ease if the Turks allowed television and radio broadcasts in the Kurdish language and restored the Kurdish names to villages that now have Turkish names.

Kurdish is written with Latin, Arabic and Cyrilic alphabets depending on which country the Kurds are in. Many Jewish and Christian Kurds speak Neo-Aramaic, derived from Aramaic, the language of Jesus, the predominant language of the Middle East before gradually being superceded by Arabic after the Muslim conquest in the 7th century.

Kurdish Religion

Orthodox Christian Kurds with a Greek Orthodox priest

The majority of Kurds are Sunnis but they generally regard themselves as Kurds first and Sunnis second. There are also many Christians, even Jewish, Kurds and followers of the Yazidi religion, which has its roots in Sufism and Zoroastrianism. Kurds have traditionally not been drawn to Muslim or religious extremism. A number of Kurds are Sufis.

Islam spread among the Kurds in the seventh and eighth centuries. Many Muslim rites and beliefs coexisted with pre-Islamic cults associated with lakes, stones, graves, trees, fire, and an ancestor cult. Among the Muslim Kurds reverance toward pirs (holy places) was widespread. Three types of these were distinguished. The first—stone mounds, formed by the casting of stones at places considered sacred—were revered primarily by the nomadic Kurds. Part of the mound was frequently covered by pieces of fabric hung on bushes or saplings by women. The Kurds believed that these pirs would save them from misfortune. The second type, created by sedentary Kurds, was associated with the graves of saints and the cult of the ancestors. On certain days the villagers brought offerings, usually baked bread and sweets, to these graves. The third kind reflected the cults of trees, stones, and water; these cults had devotees among both the sedentary and nomadic population. [Source: Encyclopedia of World Cultures]

The beliefs and rites of the Yazidi Kurds are strictly clandestine; no one who is not born a Yazidi can have access to them. The Yazidis recognize the existence of two principles—a good one, embodied in God, and an evil one, embodied in Malek-Tauz (represented as a peacock). They have cults associated with fire, the moon, trees, water, stones, and the sun. Malek-Tauz is depicted in the form of a bird standing on a high bronze or brass pedestal (senjag or sanjaq ). The founder of the sect of the Yazidis was Sheikh Adi, who lived in northern Mesopotamia (Iraq) in the twelfth century. His temple is located 70 kilometers from the city of Mosul. The Yazidis have their own sacred books, written in the thirteenth century: the Kitabe Jilva (Book of the Revelation) contains the essence of Yazidi dogma, and the Maskhafe Resh (Black Book) sets forth the legend of Yezid, son of Moawiya, and the various rites and customs.

Kurdish Jews

Kurdish Jew in the 1930s

Kurdish Jews live predominately in mountainous areas of Kurdistan in Turkey and Iraq. They have traditionally been isolated from other Jewish groups and spoke Kurdish and a Neo-Aramaic language related to Aramaic, the language spoken throughout the Middle East before being superceded by Arabic after the Muslim conquest in the 7th century. [Source:Encyclopedia of World Cultures]

Kurdish Jews have traditionally worked as farmers, shepherds and loggers, jobs usually not associated with Jews. Many had vineyards or orchards. Some also worked as traders and artisans. Those that worked as peddlers and traveled from town to town by donkey, trading basic goods, were the targets of raids by Kurdish brigands. Over time the Jews moved from villages, which were often raided, and moved to more secure cities. Few got rich.

Jewish Kurds are not known for being very religious or even very Jewish. Marriage customs of Kurdish Jews have traditionally matched those of Muslim Kurds. Not many have spoken Hebrew. Emphasis was generally placed more on the spoken word at sermons at synagogues than among the written word, with a strong emphasis on Biblical stories to make moral points and discussions of miracles and coming messiahs. The religious life of Kurdish Jews also included wearing of amulets, help from mystics and visit to shrines that promised to help cure the sick and help barren women have children.

Kurdish Jewish storytellers and bards are known among Jewish and non-Jewish Kurds alike for their oral skills. The stories were often well known to the audience and the storytellers skill was measured in term of expressions, gesture and ability to make sound effects and a variety of voices. , Kurdish Jewish women were famous for the elaborate jewelry, including nose rings and foot bracelets they wore on their wedding day.

History of Kurdish Jews

Yazidi Kurd

According to tradition Kurdish Jews are descendants of Jews from the Lost Tribes of Israel who were exiled from Judea by the Assyrian kings. Scholars that have looked into the matter have said there is some evidence to back up these claims. Some are also believed to be descendants of Jews that fled to Kurdish areas when Crusaders persecuted Jews in the Middle East in the 12th century. [Source: Encyclopedia of World Cultures]

At the end of World War II there were about 25,000 Kurdish Jews living scattered across Kurdistan in about 200 villages and small towns. Because these communities were scattered and isolated from one another by rugged terrain, the inhabitants of each village spoke a different dialect. What little unity they had was often via Jews living in the cities of Turkey and Iraq. Often there were small Christian Kurdish communities living side by side with the Jewish ones.

Most Kurdish Jews emigrated to Israel in 1950 and 1951. The number of Jewish Kurds living in Israel is about 100,000. These include the dwindling number of those who emigrated and their descendants. Many live in the Jerusalem area. Some Israelis regard the Kurdish Jews as the lowest of the low. Many Kurdish Jewish women work as maids and the men work as manual laborers, masons and stone cutters. A few worked their way up from humble beginning to be some of the wealthiest people in Israel, owning restaurants, hotels and supermarkets. The construction business in Jerusalem has traditionally been dominated by Kurdish Jews.

Kurdish Life

Kurds often are a bit suspicious of outsiders at first. Their biggest holiday is “Nevroz”, the Kurdish New Year, which is normally celebrated in the spring. Nevroz honors a legendary tinsmith who slayed a giant monster. Food in traditional Kurdish homes, says Hitchens, is usually prepared in aluminum pots and passed around. Men help themselves first and then boys take their turn. Women and girls get what remains, but there is usually plenty to go around.

Kurdish women tending a flock of goats

Kurds have been described as quarrelsome, proud, independent, They are known for stubbornness, infighting and fierceness. In some Kurdish areas in the 1990s every boy over the age of 12 carried an automatic weapon and younger ones carrying knives. When journalist Christopher Hitchens complimented a Kurdish man for having charming children, he responded by saying, "Yes, they will make good soldiers." This tradition of fierceness goes way back. When Alexander the Great's army returned from a battle with the Persians, it had more problems with harassment from Kurdish bandits than it did with the Persians.♠

The primary occupation of the Kurds of Transcaucasia in the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth was the vertical transhumance of livestock. Before departing for the pastures in the spring, the Kurds would form into obas, temporary and voluntary unions of several large families that lasted until their return to winter quarters in late fall. The fundamental objective in the creation of the oba was the assurance of adequate care and maintenance for the cattle. Obas were either of the jol type, in which members contributed equally toward the upkeep of the cattle, or the type in which one of the more prosperous flock owners accepted the sheep of the other members of the oba into his flock. The number of families forming an oba depended on the number of sheep and goats owned by each family. In addition to nomadic cattle rearing there was also cattle rearing in pastures. A number of tribes combined pasturing of livestock with dry-land agriculture (grains, tobacco). [Source: Encyclopedia of World Cultures]

See Persecution of Kurds, Kurdish Relations with Turkey

Kurdish Marriage

Marriages between cousins or at least members of the same tribe are preferred. A marriage of a young man to his father’s brother’s daughter is regarded as the ideal match and entails the exchange of a high bride price. Such unions keep wealth within the family and assures obedience of the bride to the son and the mother in law. The arrangement often suited the bride. She didn’t have to join a new tribe or village and could remain close to her parents and family.

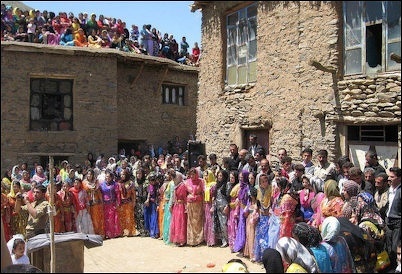

wedding celebration in a Kurdish village

Girls have traditionally married at age 15 or 16, often to much older men.. Polygamy remains in many parts southeast Turkey. There have been a number of cases of teenage girls who committed suicide because they were forced to marry men three or four times their age who already had several wives and lots of children.

In the old days, Kurds used to kidnap non-Kurds who had fallen in love with Kurdish girls and kill them, leaving their bodies at the homes of their families. In Iraq, sometimes women brought Kalashnikov’s to weddings in case violence broke out between attending clans.

A man is expected to provide a dowry, known as head money, of around $1,200 (early 2000s prices), plus about $4,000 for the wedding. A guy earning $250 a months needed several years to save up this much. A high price is around $12,000, Some reach $50,000. The price is usually determined on the basis of looks, status and wealth. The government has tried to abolish head prices but has not had much success. There have been many cases of boys who couldn’t come up with the head money and eloped their brides only to be victims of honor killings along with their brides.

Kurdish Society and Families

Originally Kurds formed a mostly rural society. Traditional tribal villages included nomadic and semi-nomadic groups. Tribal traditions and customs are still very strong among the Kurds. Kurdish society is based on feudal and clan traditions. Even among urban Kurds tribal identification remains strong.

Kurds have been known to have blood feuds that have lasted for generations. One man who vowed to kill a Kurdish tribal leader to avenge the death of his uncle told the New York Times, “There is blood between us, and every day, every minute of every day, I think of killing him. It is like a dream in my mind.”

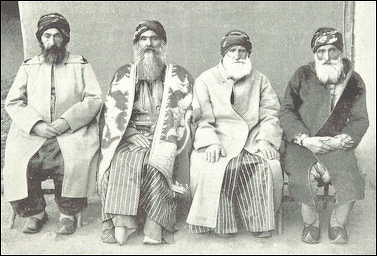

Kurdish chiefs in 1895

Kurds place a great importance on large families. Kurds have traditionally had lots of children. In the old days, the infant mortality rate was high, sometimes 50 percent.

In Kurdistan everyone seems related to everyone else and cousins are often encouraged to marry to keep farms and orchards in the family. The senior mother is regarded as the boss. The person she pushes around the most is her daughter-in-law. Daughters-in-law are subjected to endless chores ad expected to bear a child, preferably a boy, every year.

According to Hitchens Kurdish men are strong and animated. They are big talkers, and sing and dance with passion and enthusiasm. Kurdish women generally enjoy more freedoms than their Arab, Iranian and Turkish counterparts. Kurdish women do not wear the veil. They are welcome to socialize with men and can pursue careers. They can also go to jail just like the men. One woman was given 12½ years in a Turkish prison for being a suspected member of the PKK. Kurdish women wear lots of gold and silver bracelets. This in essence is the family's wealth. And, unlike Arab women, Kurdish women like to be photographed. ♠

Honor Killing Among Kurdish Women

Honor killings are particularly common among Kurdish women. In and around the town of Sanliurfa in southern Turkey, a teenage girl had her throat slit by her 11-year-old brother because someone dedicated a love song to her on the radio (she was a virgin and didn’t have a boyfriend). In the same place a 12-year-old was killed by her 17-year-old husband because he went to the movies without his permission.

The Los Angeles Times reported the case of a 14-year-old Kurdish girl in Sanlurfa who was raped by her neighbor’s son. Her father felt their family was dishonored and felt the only way out was to kill her. He ordered his two son to take her to a field and drown her in an irrigation ditch. The only reason this story became known is that she survived and reported what happened to the police. Her brother, who also killed the rapist, were arrested along with nine other relatives. She was taken to a state-run institution in an undisclosed location. Even the girl’s mother said she “accidentally” feel into the water. “That stupid child shamed our entire family,” she said. “We could not show our faces to the neighbors, not even to the shopkeepers, and now all our men are in jail.”

Kurdish holik (shelter)

Some of the worst honor killings have been reported in Europe and North America. In 2005, Hatun Surucu, a 23-year-old woman from a Turkish-Kurdish family was killed by her 18-year-old brother in Berlin for having a child outside of marriage and dating German men among other offenses, The brother even bragged to his girlfriend about what he had done. He received a prison sentence of nine years and three months.

Kurdish Homes

Nomadic Kurds traditionally lived in tents while settled Kurds lived in permanent homes in mountain valleys. The nomads lived in heavy, black tents in the winter and lighter tents in the summer. A camp might consist of an entire clan or a group of families.

Settled Kurds traditionally lived in low clay or stone houses with flat roofs. They are often built on slopes in such a way the roof of one houses serves as terrace for the house above it. Some villages consist almost entirely of families from a single lineage. Others are made up of members from several lineages. Pastures were often owned communally. Land if it was allowed to be sold was generally only allowed to be sold to other villagers.

Many Kurds live in small whitewashed brick shanties with small windows and flat roofs. They have no or little furniture. Dirt floors are covered with rugs and people sit on foam rubber pads. Affluent families have Persian carpets and long rectangular cushions. Kurds have traditionally slept on a north-south axis. For a long time, few people can afford air conditioners or even fans. ♠

During the summer, many areas where many Kurds live are so hot that people sleep on the roofs of their homes. Many families sleep on mattresses that are set up on large metal platforms that look like cribs. The roof is also regarded as safe from intrusions by snakes and scorpions. By some counts four out to every five families in part of the southeast slept on their roof.

In southeast Turkey there have been a number of reports of children breaking bones and even dying after the woke up in the middle of the night, thought they were inside their house, and accidentally walked off the roof. According to some sources falling off roofs is the second leading cause of child fatalities after traffic accidents.

Kurdish Settlements in Armenia and Azerbaijan

Among the Kurds of Armenia, patronymic and kin-tribal settlements existed up to the 1930s and 1940s, which attests to the long retention of traditional family structures. The majority of Azerbaijani Kurds seem not to have retained a memory of their clan and tribal backgrounds; this is reflected in the settlement patterns of Kurdish villages in Azerbaijan. A village was usually founded near a spring. Public buildings did not exist in the villages. Some Muslim villages had a religious school (mekteb ); among the Yezidis, the children of well-off parents studied at the homes of the sheikhs. Kurdish villages had no mosques for Muslim Kurds or prayer houses for Yezidi Kurds. [Source: Encyclopedia of World Cultures]

Two Hawrami girls gaze at a mountainside settlement

In Azerbaijan the Kurds prayed in the Azerbaijani mosques; in Armenia, where Yezidi Kurds predominated, the religious functions of the village were celebrated in the house of the sheikh. The villages had no markets or market squares; Kurds went to Armenian or Azerbaijani villages to buy or sell produce and the products of home industry. Kurdish graveyards were located near the village. Kurds in Armenia had patronymic graveyards; those in Azerbaijan had nonpatronymic graveyards alongside Azerbaijano-Kurdish graveyards. In the 1920s to the 1930s the Kurdish village gradually changed. In the republics of Transcaucasia new villages began to be created for those who had adopted a sedentary form of life. The Soviet state rendered material assistance to Kurdish peasants in the construction of new settlements. In the major Kurdish towns, particularly in Armenia, new dwellings, farms, and mills were erected. The new towns had sociocultural and economic centers with village soviets, schools, and reading rooms. The results of this process were especially evident in the Kurdish villages of Armenia in the 1950s to the 1980s.

The change in the external appearance of the Transcaucasian Kurdish villages is connected with a change in the way of life and the dwelling place. Until the beginning of the twentieth century the basic types of habitation were the tent (kon, chadïr, reshmal ) for the nomadic and seminomadic population, and the winter dwelling (mal, khani ), an underground or half-underground mud hut for the seminomadic and sedentary population. The Kurdish homestead was a single, horizontally oriented complex consisting of an underground or half-underground hut, stable, sheepfold, and storeroom (in some parts of Azerbaijan, the oreintation was vertical). The main construction material was unfinished brick, unpolished stone, or sometimes tufa (in Armenia). Houses in the plains had flat roofs, those in the mountains cupola-shaped roofs with an aperture (kolek ) in the ceiling for light and smoke. The ceiling beams rested on wooden columns (stun ). A hearth (tandur ) in the earthen floor was used to heat the home, bake bread, prepare food, and enact ritual ceremonies. The hearth has a sacred place in the life of the Kurds.

Kurdish Food

The Kurds have a distinctive national cuisine. Kurds that still practice their nomadic ways live off milk, yoghurt and other sheep products, which they also sell at markets. Common ingredients in Kurdish food include tomatoes, green peppers, onions, yoghurt, bulgur wheat, flour, lentils, cooking oil, chick peas, sugar, Arab-style bread. Meat comes from sheep. Live chickens and rabbits are sold in the markets.

making bread on a round hot iron

The staple of the Kurdish diet is a pancake-thin bread called “tiroq” which is baked in clay, open- hearth ovens that often are buried under ground. Bread with sesame is popular. Common dishes include okra soup, rice wrapped in grape leaves and goat stew with tomatoes, green peppers, onions and green beans. Goats, sheep and cows are raised for milk and meat. Some of the milk is heated and spiked with a little bit of day old yoghurt. After it sits for a while the milk is then shaken back and forth inside a goat skin and fresh yoghurt is scraped off the inside.♠

Heavily sugared tea from a brass samovar is consumed all day long. In some places in the mountains, people give pack animals alcohol in the winter to keep them warm. Some Kurds smoke from pipes with long tubes.

From the beginning of spring the women stock up on produce (dairy products, meat, cereal, flour, vegetables) for the fall and winter. Semiprocessed dairy products are frequently used in many dishes, for example the refreshing beverage dau, from which various soups and curds are prepared. Curds can be fashioned into small balls (kyashk ) that are dried under the burning sun. In winter, when the cows' milk yield drops and it is impossible to get dau, Kurds crumble a ball of kyashk, soak it overnight in warm water, and consume the thick liquid the following day. They also make various sorts of cheese (e.g., panire sari and a stringy cheese called panire reshi ) Meat dishes include grilled mutton and Caucasian shashlik. Among the more common cereal dishes are porridges and soups prepared from processed grains (wheat, barley, and rice). Noodles (reshte ) made from flour are prepared for storage. [Source: Encyclopedia of World Cultures]

Kurdish Clothes

Some Kurdish women paint their eyes with three different colors and wear long gowns, embroidered jerkins, scarfs and black handbands. Older Kurdish men wear turban-like head scarves and like to smoke cigarettes with long holders. Males or all ages wear baggy trousers wrapped tightly around their ankles and often held up with cummerbunds. Kurdish men are said to be fond of bright colors. As his last request one famous Kurdish bandit wanted to be hung with a red and green rope. Kurdish women have traditionally gone unveiled

Kurdish women's clothes in the late 1800s

In the old days, many Kurds wore turbans with tasseled headgear along with bandoliers. In Iran Kurdish men wear a short, thigh-length jacket, fastened to the neck and open down the front, white shirts with very long sleeves which are wrapped around the jacket. The white or colored turbans are fringed and tied so the fringe hangs down over the face and acts as a “fly whisk.”

Older women still wear the national costume, consisting of a shirt (kras ), baggy pantaloons (khevalkras ), vest (elek ), skirt (navdere, tuman ), apron (salek ), armlets (davzang ), woolen belt (bene peste ), hat (kofi, fino ) or silk head shawl, woolen stockings (gore ), and shoes. Ancient and modern decorations of all types (beads, rings, earrings, bracelets) and gold and silver coins on the kofi headgear are an obligatory component of female dress. In the past, Kurdish women wore nose ornaments (kerefil ) and foot ornaments (kherkhal ). The men's folk costume as a whole has gone out of use, but individual elements were worn until the first half of the twentieth century in Azerbaijan. The traditional national costume of the Kurds of Transcaucasia consisted of a shirt, wide trousers, a vest, a woolen belt, woolen socks, and shoes. A dagger thrust in the belt was formerly regarded as an inseparable element of the masculine costume. [Source:

Kurdish Culture, Music and Literature

There is famous Kurdish fable about a nightingale that was captured a put in a gilded cage Despite it lavish surrounding it cried every night to return to its simple nest. A ban on Kurdish publications and music was lifted in Turkey in 1991 but censorship has endured. In 1991, a group of Kurds established a foundation to promote Kurdish culture. It was given legal status in 1996 as the Kurdish Cultural and Research Foundation.”

The Kurdish nation is justifiably proud of its extremely rich oral literature—poems, tales, songs, proverbs, and legends, many of which have achieved popularity among other peoples (Armenians, Azerbaijanis, Persians, Turks, Arabs, and Assyrians). Kurdish folklore extols the moral beliefs of the people: reverence for elders (particularly women), hospitality, courage, valor, and the love of freedom. Among the most widespread Kurdish epics are "Mam i Zin," "Dïmdïm," and "Zambilfrosh." [Source: Encyclopedia of World Cultures]

Kurdish musicians in 1890

One thing that unifies the Kurds is their music. Traditional Kurdish culture has endured thanks to “dengbej” (bards), “stranbej” (popular singers) and “cirobej” (storytellers) who learned hundreds of love songs, legends, myths and stories, performed them at events and gatherings and passed them down to the next generation. Among the most highly regarded dengbejs are Sivam Perwar and Temo, who now live in Europe.

Traditional Kurdish instruments include the “blur” and “duduk” (wind instruments), best played in a valley that produces an echoing effect, and “tembur” and “saz” (string instruments), “dirhool” (drums) and “zirna” (pipe). The “blur” is a Kurdish shepherd’s flute made from a branch of mulberry or walnut and containing seven to nine finger holes.

Kurds often sit glued to cassette players listening to singers like Juwan Hajo, a Syrian Kurd, and Ibrahim Tatlises, an arabesque singer who sings mostly in Turkish for Turkish listeners. Most of the cassettes sold are bootlegs.

Smuggling and Kurdish Economics

There is a lot of oil of Kurdish territory n Iraq. The Kurds were once a nomadic people. Now most of them are farmers, or have migrated to the cities. They have traditionally raised sheep and goats and grown vegetables and tended almond trees. There used to be and still are lots of Kurdish shepherds. In some places in the mountains, people give pack animals alcohol in the winter to keep them warm.

Kurds have a long history of smuggling. The Iraqi Kurdish government earns income from taxes on trucks crossing the Turkish border. In the 2000s everything was in short supply except for weapons and cigarettes. Nearly every Kurdish male over 13 carried an assault weapon and guns were sold openly in the markets that don't have any fruit, medicine or milk. ◂▸

Kurds celebrating Nawroz (Near Year) in Palangan village in Hawraman

A huge cigarette black market sprung up in the security zone in Iraq in 1990s duing the Saddam Hussein era.. Duty-free cigarettes that came in from Cyprus and Turkey were smuggled into southern Iraq, Iran and back into Turkey for a handsome profit. The merchants that ran the trade zoom around the countryside in new Mercedes and signed one or two million dollar contracts for the cigarettes. Smugglers transport the contraband over remote passes on mules or across lakes with wooden boats for a $100 per trip. Border guards have orders to shoot. In the first half of 1994 five smugglers had been killed and two dozen were wounded. [Chris Hedges, New New York Times, August 17, 1994]

The supply line for other goods works something like this. Trucks come to Iraq from Turkey with empty gasoline containers. The drivers trade Turkish food for Iraqi gasoline which sells for less than one cent a liter. The trade violates the UN embargo but most officials look the other way in that people in Iraq would have no other means of getting food.

In Iraq in the 1990s if someone asked you "how many Saddams you have" he meant "how much money do you have." Saddam Hussien's face graced the banknotes of most Iraqi money. The Iraqi Kurdish nationalist movement had a bunkered television station which broadcasts 15 hours of programming each day to over six million people. Among the shows were "slapstick parodies of Saddam Hussein's speeches by a bloated look-a-like."∝ ♠

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994). “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, BBC, Al Jazeera, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018