MYSTICAL ECSTASY IN THE 10TH CENTURY

Sufi in ecstasy

“Ruminations and Reminiscences,” Al-Tanûkhî wrote in A.D. 980: “I saw in Baghdad a one-eyed Sufi, named Abu'l-Fath, who was chanting the Qur'an beautifully in a gathering arranged by Abu 'Abdallah Ibn al-Buhlul. A lad read the text (Qur'an xxxv: 34) Did we not give you length of life sufficient for a man to take warning in? The Sufi cried out Aye, aye many times and fainted, remaining unconscious during the whole of the meeting. He had not recovered when the congregation dispersed, the meeting having been held in the court of a house which I inhabited. I left him where he was, and he did not come to himself till about the afternoon, when he arose. [Source: D. S. Margoliouth, ed., The Table Talk of a Mesopotamian Judge, (London: Royal Asiatic Society, 1922), pp. 64-67, 164-68, 135-37, 93, 2 9-92, 86-87, 31, 160, 97-101, 172-73, 84-86, 204-6]

“After some days I inquired about him, and learned that he had been present in Karkh when a singing-woman was performing to the lute, and heard her repeat the lines in which comes the passage The day when each man brings his plea, Thy blessed face shall plead for me. This affected him so much that he shouted and beat his breast and at last fell down in a fit.

“When the entertainment was over they moved him and found that he was dead. He was taken away for burial and the affair got noised abroad. The verses whence this is taken are by 'Abd al-Samad bin al-Mu'adhdhal; they were dictated by Suli after him by a chain recorded in my records of traditions which I have heard; they were: Author of ways which fascinate, Thou art the sovereign of our fate. A house with thee for habitant Needeth not an illuminant. If e'er release from thy control I crave, may God not save my soul! The day when each man brings his plea, Thy blessed face shall plead for me.”

Websites on Sufis Divisions in Islam archive.org ; Sufism in the Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World williamcchittick.com ; Sufism, Sufis, and Sufi Orders – Sufism's Many Paths islam.uga.edu/Sufism ; The Threshold Society sufism.org ; Mysticism in Arabic and Islamic Philosophy, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu ; Risala Roohi Sharif, translations (English and Urdu) of "The Book of Soul", by Hazrat Sultan Bahu, a 17th century Sufi risala-roohi.tripod.com ;Sufism - an Inquiry sufismjournal.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Garden of Truth: The Vision and Promise of Sufism, Islam's Mystical Tradition” by Seyyed Hossein Nasr Amazon.com ;

“Living Presence (Revised): The Sufi Path to Mindfulness and the Essential Self”

by Kabir Edmund Helminski, Iman Amazon.com ;

“Essential Sufism” by James Fadiman, Huston Smith, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Principles of Sufism” by ʿAʾishah al-Bauniyyah Amazon.com ;

“Hidden Caliphate: Sufi Saints beyond the Oxus and Indus” by Waleed Ziad Amazon.com ;

“Winds of Grace: Poetry, Stories and Teachings of Sufi Mystics and Saints”

by Vraje Abramian Amazon.com ;

“Women of Sufism: A Hidden Treasure” by Camille Adams Helminski Amazon.com ;

“Al-Ghazali's Path to Sufism: His Deliverance from Error” by Abu Hamid Muhammad al-Ghazali (Author) Amazon.com ;

“The Mysticism of Sound and Music: The Sufi Teaching of Hazrat Inayat Khan Amazon.com ;

“Sufi Music of India and Pakistan: Sound, Context, and Meaning” by Regula Burckhardt Qureshi Amazon.com

Religious Trickery in the 10th Century

In “Ruminations and Reminiscences,” Al-Tanûkhî wrote in A.D. 980: “The following was told me by Abu'l-Tayyib Ibn 'Abd al-Mu'min: An accomplished knight of industry went from Baghdad to Hims, accompanied by his wife, and when he had got to the latter place, he said to her: This is a foolish and wealthy town, and I wish to bring off a "stunner" (a phrase used by these people whereby they mean a great piece of khavery), for which I want your help and endurance. She accorded it willingly. He told her she was to remain in her place and not pass by his at all, only each day to take two-thirds of a ratl of raisins and the same quantity of almond-paste, to knead them together and place it at midday on a clean tile in a certain lavatory near the mosque where he would find it. That was absolutely all she was to do, and she was not to approach his quarters. She agreed, and then he produced a tunic and breeches of wool which he had brought, and a veil to put over his head, and took up his station by a pillar in the mosque before which most of the people passed. [Source: D. S. Margoliouth, ed., The Table Talk of a Mesopotamian Judge, (London: Royal Asiatic Society, 1922), pp. 64-67, 164-68, 135-37, 93, 2 9-92, 86-87, 31, 160, 97-101, 172-73, 84-86, 204-6]

faquir

Here he remained praying the whole day and the whole night, except at the time wherein prayer is forbidden, and when he sat down to rest he kept counting his beads and did not utter a word. For a time he was unnoticed; then he began to attract attention, and he was watched for a space and talked about and observed; it was found that he never ceased praying, and never tasted food. The people of the town were astonished at him, as he never left the mosque save once at midday, when he went to the lavatory and made his way to the marked tile whereon the paste was laid, which had changed color and looked like dried and discolored dung, which those who came in and out supposed it to be. This he would eat to support life, after which he would come back and drink as much water as he required, when he was washing for the nightly prayer and during the night. The people of Hims supposed that he tasted neither water nor food, and that he maintained a complete fast during the whole period; and this they thought extraordinary, and admirable. Many approached him and addressed him, but he returned no answer; when they surrounded him he took no notice, and however hard they tried to get him into conversation, he maintained silence and his line of conduct, so that he won their profound respect; and indeed when he went for purification, they went to the place which he had been occupying and rubbed their hands thereon or carried away the dust from the places where he had walked; and they brought to him the sick that he might lay his hands on them.

“When a year had passed in this performance, and he perceived what respect he had won, he had a meeting with his wife in the lavatory, where he told her on the following Friday when the people were praying, to come, seize hold of him, and smite him on the face, and say to him: You enemy of Allah, you scoundrel, after killing my son in Baghdad, have you come here to play the devotee? May your face be smitten with your devotion! You are not, he said, to let me go, but pretend that you want to slay me to avenge your son; the people will gather against you, but I will see that they do you no harm, as I shall admit that I have killed him, and pretend that I have come to this town to do penance, and practice devotion in order to expiate my offence. You are then to demand that I be driven out of the mosque and brought to the magistrate for execution; the people will then offer to pay blood-money, but you are not to accept less than ten times the legal amount or what, from the eagerness with which they raise their bids, you gather that they are prepared to pay. When the bidding has reached a point beyond which they seem to you unlikely to go in their efforts to redeem my life, then accept the ransom, collect it and leave the town at once for the Baghdad road; I will escape and follow you.

Sufi Rohal Faqir

“The next day the woman came to the mosque, and when she saw him, she did what he had bidden her, buffeted him on the face and recited the speech which he had taught her. The people of the town rose up wishing to kill her, saying: Enemy of Allah, this is one of the chief saints, one of the maintainers of the world, the Pole of the time, the lord of the age, and so on. He signalled to them to be patient and not to hurt her, shortened his prayer, said the benediction, then rolled for a long time on the ground, and then asked the people whether since he had been living among them they had heard him speak a word. They were delighted to hear his voice, and a loud cry of No! gave the answer to his question. He then said: The reason is that I have been living among you to do penance for the crime she mentioned; I was a man who erred and ruined himself murdering this woman's son; but I have repented and came here to practice devotion. I was thinking of going back to her and looking for her that she might demand my blood, fearing lest my penitence might not be true; and I have constantly been praying God to accept my penitence and put me into her power until at last my prayer has been answered, and it is a sign that God has accepted my prayer that he has brought us together and put it into her power to obtain retaliation; suffer her therefore to slay me and I commit you to the care of God. Cries and lamentations then arose, and one after another implored him to pray for him. The woman advanced in front of him as he moved, walking slowly and deliberately to the door of the mosque, with the intention of going thence to the palace of the governor of the place, that the latter might order him to be executed for the murder of her son.

“Then the sheikhs said: Citizens, why have you forgotten to remedy this disaster and protect your country by the presence of this saint? Deal gently with the woman and ask her to accept the blood-money, which we shall pay out of our purses. The woman said: I refuse. They said: Take twice the legal amount. She said: One hair of my son's head is worth a thousand times the legal amount! They went on bidding until they had reached ten times the amount; then she said: Collect the money, and when I have seen it, if I feel that I can accept it and acquit the murderer, I will do so; if not, then I shall slay the slayer. They agreed to do this. Then said the man to her: Rise up, God bless you and take me back to my place in the mosque. She declined and he said: As you will. The congregation went on collecting money until they had got together a hundred thousand dirhems, which they asked her to accept. But she said: I will take nothing but the death of my son's murderer; so deeply has it affected my soul! Thereupon the people began to fling down their coats and cloaks and rings, the women their ornaments and every man some of his possessions, any one who was unable to bear part of the ransom being in a terrible state, and feeling like an outcast from society. At last she took what was offered, acquitted the man and went off.

Sufi Budhal Faqir

“The man remained in the mosque a few days-long enough for her to get to a safe distance—and himself decamped one night. When he was sought the next day he could not be found nor was he heard of until a long time after when they discovered that the whole affair had been a plot.

“I was informed by Abu'l-Hasan Ahmad bin Yusuf al-Azraq as follows. I had heard, he said, how Husain bin Mansur al-Hallaj would eat nothing for a month or so though he was under close inspection. I was amazed thereat, and since there was a friendship between me and Abu'l-Faraj Ibn Rauhan the Sufi, who was a pious and devout traditionalist, and whose sister was married to Qasri, attendant of Hallaj, I asked him about this; he replied: I do not know how Hallaj managed, but my brother-in-law Qasri, his attendant, practiced abstinence from food for years and by degrees got to be able to fast for fifteen days, more or less. He used to manage this by a device which had escaped me, but which he divulged when he was imprisoned with the other followers of Hallaj. If a man, he said, be strictly watched for some length of time, and no trickery be discovered, the scrutiny becomes less strict, and continues to slacken as fraud fails to appear, until it is quite neglected, and the person watched can do what he likes. These people have been watching me for fifteen days wherein they have seen me eat nothing, and that is the limit of my endurance of famine; if I continue to fast for one day more I shall perish. Do you take a ratl of raisins of Khorasan and another of almonds and pound them into the consistency of oil-dregs, then make them into thin leaf. When you come to me to-morrow place it between two leaves of a note-book, which you are to carry openly in your hand, so rolled up that its contents may not break nor yet be seen. When you are alone with me and see that no-one is watching, then put it under my coat-tails and leave me; then I shall eat the cake secretly, and drink the water with which I rinse my mouth for the ceremonial washing, and this will suffice me for another fifteen days, when you will bring me a second supply in the same style. If these people watch me during the third fortnight, they will find that I eat nothing in reality until you pay your periodical visit with supplies, when I shall again escape their notice when I eat them, and this will keep me alive. The narrator added that he followed these instructions the whole time the man was in prison.

Acts of Prodigality in the 10th Century

In “Ruminations and Reminiscences,” Al-Tanûkhî wrote in A.D. 980: “Mutawakkil [Caliph, r. 847-860] desired that every article whereon his eye should fall on the day of a certain drinking-bout should be colored yellow. Accordingly there was erected a dome of sandalwood covered and furnished with yellow satin, and there were set in front of him melons and yellow oranges and yellow wine in golden vessels; and only those slave-girls were admitted who were yellow with yellow brocade gowns. The dome was erected over a tesselated pond, and orders were given that saffron should be put in the channels which filled it in sufficient quantities to give the water a yellow color as it flowed through the pond. This was done, and as the drinking-bout was protracted their supplies of saffron were exhausted and safflower was used as a substitute, they supposing that he would be intoxicated before this was exhausted, or they could incur reproach. It was exhausted, and when only a little remained they informed him, fearing that he would be angry if the supply stopped, while the want of time made it impossible for them to purchase more from the market. When they told him, he blamed them for not having laid in a large stock; and telling them that if the yellow water ceased, his day would be spoiled, he bade them take fabrics that were dyed yellow with qasab and soak them in the channel that the water might be colored by the dye which they contained. This was done, and all the fabrics of this sort in the treasury were exhausted by the time he was intoxicated. The value of the saffron, safflower and ruined fabrics was estimated and came to fifty thousand dinars. [Source: D. S. Margoliouth, ed., The Table Talk of a Mesopotamian Judge, (London: Royal Asiatic Society, 1922), pp. 64-67, 164-68, 135-37, 93, 2 9-92, 86-87, 31, 160, 97-101, 172-73, 84-86, 204-6]

From Jalal al-Din Rumi, Maulana: A Man Questions a Preacher about the Meaning of the Direction a Rooster Faces While on the Roof

“Another, I am told, was in a hurry to get rid of his money, and when only five thousand dinars were left, said he wanted to have done with it speedily in order that he might see what he would do afterwards.... Then one of his friends advised him to buy cut glass with the whole sum, all but five hundred dinars, spread the glass, which should be of the finest, out before him and expend the remaining dinars in one day on the fees of singing women, fruit, scent, wine, ice, and food. When the wine was nearly drained he should set two mice free in the glass, and let a cat loose after them. The mice and the cat would fight amid the glass and break it all to pieces, and the remains would be plundered by the guests. The man aproved the notion, and acted upon it. He sat and drank and when intoxicated called out Now! and his friend let loose the two mice and the cat, and the glass went crashing to the amusement of the owner, who dropped off to sleep. His friend and companions then rose, gathered together the fragments, and made a broken bottle into a cup, and a broken cup into a pomade jar, and pasted up what was cracked; these they sold amongst themselves, making up a goodly number of dirhems, which they divided between them; they then went away, leaving their host, without troubling further about his concerns. When a year had passed the author of the scheme of the glass, the mice and the cat said: Suppose I were to go to that unfortunate and see what has become of him. So he went and found that the man had sold his furniture and spent the proceeds and dismantled his house and sold the materials to the ceilings so that nothing was left but the vestibule, where he was sleeping, on a cotton sheet, clad in cotton stripped off blankets, and bedding which had been sold, which was all that was left for him to put under him and keep off the cold. He looked like a quince ensconced between his two cotton sheets. I said to him: Miserable man, what is this? What you see, he replied. I said: Have you any sorrow? He said he had. I asked what it was. He said: I long to see some one—a female singer whom he loved and on whom he had spent most of his wealth. His visitor proceeds: As the man wept, I pitied him, brought him garments from my house which he put on, and went with him to the singer's dwelling. She, supposing that his circumstances had improved, let us enter, and when she saw him treated him respectfully, beamed on him, and asked how he was doing. When he told her the truth, she at once bade him rise, and when he asked why, said she was afraid her mistress would come, and finding him destitute, be angry with her for letting him in. So go outside, she said, and I will go upstairs and talk to you from above.

“He went out and sat down expecting her to talk to him from a window on the side of the house which faced the street. While he was sitting, she emptied over him the broth of a stewpan, making an object of him, and burst out laughing. The lover however began to weep and said: O sir, have I come to this? I call God and I call thee to witness that I repent. I began to mock him, saying: What good is your repentance to you now? So I took him back to his house, stripped him of my clothes, left him folded in the cotton as before, took my clothes home and washed them, and gave the man up. I heard nothing of him for three years, and then one day at the Taq Gate seeing a slave clearing the way for a rider, raised my head and beheld my friend on a fine horse with a light silver-mounted saddle, fine clothes, splendid underwear and fragrant with scent—now he was of a family of clerks and formerly in the days of his wealth, he used to ride the noblest chargers, with the grandest harness, and his clothes and accoutrements were of the magnificent style which the fortune inherited by him from his parents permitted. When he saw me, he called out: Fellow! I, knowing that his circumstances must have improved, kissed his thigh, and said: My lord, Abu so-and-so! He said Yes! What is this? I asked. He said: God has been merciful, praise be to Him! Home, home. I followed him till he had got to his door, and it was the old house repaired, all made into one court with a garden, covered over and stuccoed though not whitewashed, one single spacious sitting-room being left, whereas all the rest had been made part of the court. It made a good house, though not so lordly as of old. He brought me into a recess where he had in old times sought privacy, and which he had restored to its pristine magnificence, and which contained handsome furniture, though not of the former kind.

From Jalal al-Din Rumi, Maulana: A Man Kills his Mother, who has Committed Adultery

“His establishment now consisted of four slaves, each of whom discharged two functions, and one old functionary whom I remembered as his servant of old, who was now re-established as porter, and a paid servant who acted as sa'is. He took his seat, and the slaves came and served him with clean plate of no great value, fruits modest both in quantity and quality, and food that was clean and sufficient, though not more. This we proceeded to eat, and then some excellent date-wine was set before me, and some date jelly, also of good quality, before him. A curtain was then drawn, and we heard some pleasant singing, while the fumes of fresh aloes, and of nadd rose together. I was curious to know how all this had come about, and when he was refreshed he said: Fellow, do you remember old times? I said I did. I am now, he continued, comfortably off, and the knowledge and experience of the world which I have gained are preferable in my opinion to my former wealth. Do you notice my furniture? It is not as grand as of old, but it is of the sort which counts as luxurious with the middle classes. The same is the case with my plate, clothes, carriage, food, dessert, wine—and he went on with his enumeration, adding after each item "if it is not super-fine like the old, still it is fair and adequate and sufficient." Finally he came to his establishment, compared its present with its former size, and added: This does instead. Now I am freed from that terrible stress. Do you remember the day the singing-girl—plague on her—treated me as she did, and how you treated me on the same day, and the things you said to me day by day, and on the day of the glass?

“I replied: That is all past, and praise be to God, who has replaced your loss, and delivered you from the trouble in which you were! But whence comes your present fortune and the singing-girl who is now entertaining us? He replied: She is one whom I purchased for a thousand dinars, thereby saving the singing-women's fees. My affairs are now in excellent order. I said: How do they come to be so? He replied that a servant of his father and a cousin of his in Egypt had died on one day, leaving thirty thousand dinars, which were sent to him and arrived at the same time, when he was between the cotton sheets, as I had seen him. So, he said, I thanked God, and made a resolution not to waste, but to economize, and live on my fortune till I die, being careful in my expenditure. So I had this house rebuilt, and purchased all its present contents, furniture, plate, clothing, mounts, slaves male and female, for 5000 dinars; five thousand more have been buried in the ground as a provision against emergencies. I have laid out ten thousand on agricultural land, producing annually enough to maintain the establishment which you have seen, with enough over each year to render it unnecessary for me to borrow before the time when the produce comes in. This is how my affairs proceed and I have been searching for you a whole year, hearing nothing about you, being anxious that you should see the restoration of my fortunes and their continued prosperity and maintenance, and after that, you infamous scoundrel, to have nothing more to do with you. Slaves, seize him by the foot! And they did drag me by the foot right out of the house, not permitting me to finish my liquor with him that day. After that when I met him riding in the streets he would smile if he saw me, and he would have nothing to do either with me or any of his former associates.

Al-Ghazali on Sufism

Abu Hamid al-Ghazali wrote in his “Confessions” (1100): “When I had finished my examination of these doctrines I applied myself to the study of Sufism. I saw that in order to understand it thoroughly one must combine theory with practice. The aim which the Sufis set before them is as follows: To free the soul from the tyrannical yoke of the passions, to deliver it from its wrong inclinations and evil instincts, in order that in the purified heart there should only remain room for God and for the invocation of his holy name. [Source: Charles F. Horne, ed., “The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East,” (New York: Parke, Austin, & Lipscomb, 1917), Vol. VI: Medieval Arabia, pp. 99-133. This was a reprint of The “Confessions of al-Ghazali,” trans. by Claud Field, (London: J. Murray, 1909)

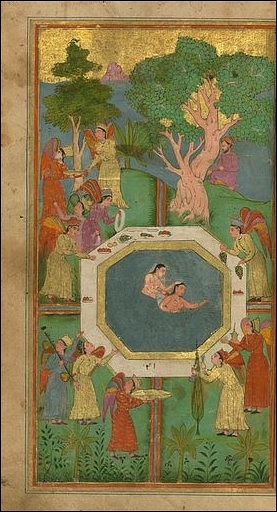

From Jalal al-Din Rumi, Maulana: Two Naked Girls in a Pool Attended by Angels

“As it was more easy to learn their doctrine than to practice it, I studied first of all those of their books which contain it: "The Nourishment of Hearts," by Abu Talib of Mecca, the works of Hareth el Muhasibi, and the fragments which still remain of Junaid, Shibli, Abu Yezid Bustami, and other leaders (whose souls may God sanctify). I acquired a thorough knowledge of their researches, and I learned all that was possible to learn of their methods by study and oral teaching. It became clear to me that the last stage could not be reached by mere instruction, but only by transport, ecstasy, and the transformation of the moral being.

“To define health and satiety, to penetrate their causes and conditions, is quite another thing from being well and satisfied. To define drunkenness, to know that it is caused by vapors which rise from the stomach and cloud the seat of intelligence, is quite a different thing to being drunk. The drunken man has no idea of the nature of drunkenness, just because he is drunk and not in a condition to understand anything, while the doctor, not being under the influence of drunkenness knows its character and laws. Or if the doctor fall ill, he has a theoretical knowledge of the health of which he is deprived.

“In the same way there is a considerable difference between knowing renouncement, comprehending its conditions and causes, and practicing renouncement and detachment from the things of this world. I saw that Sufism consists in experiences rather than in definitions, and that what I was lacking belonged to the domain, not of instruction, but of ecstasy and initiation.

“The researches to which I had devoted myself, the path which I had traversed in studying religious and speculative branches of knowledge, had given me a firm faith in three things—God, Inspiration, and the Last Judgment. These three fundamental articles of belief were confirmed in me, not merely by definite arguments, but by a chain of causes, circumstances, and proofs which it is impossible to recount. I saw that one can only hope for salvation by devotion and the conquest of one's passions, a procedure which presupposes renouncement and detachment from this world of falsehood in order to turn toward eternity and meditation on God. Finally, I saw that the only condition of success was to sacrifice honors and riches and to sever the ties and attachments of worldly life.

“Coming seriously to consider my state, I found myself bound down on all sides by these trammels. Examining my actions, the most fair-seeming of which were my lecturing and professorial occupations, I found to my surprise that I was engrossed in several studies of little value, and profitless as regards my salvation. I probed the motives of my teaching and found that, in place of being sincerely consecrated to God, it was only actuated by a vain desire of honor and reputation. I perceived that I was on the edge of an abyss, and that without an immediate conversion I should be doomed to eternal fire. In these reflections I spent a long time. Still a prey to uncertainty, one day I decided to leave Baghdad and to give up everything; the next day I gave up my resolution. I advanced one step and immediately relapsed. In the morning I was sincerely resolved only to occupy myself with the future life; in the evening a crowd of carnal thoughts assailed and dispersed my resolutions. On the one side the world kept me bound to my post in the chains of covetousness, on the other side the voice of religion cried to me, "Up! Up! Thy life is nearing its end, and thou hast a long journey to make. All thy pretended knowledge is naught but falsehood and fantasy. If thou dost not think now of thy salvation, when wilt thou think of it? If thou dost not break thy chains today, when wilt thou break them?" Then my resolve was strengthened, I wished to give up all and fee; but the Tempter, returning to the attack, said, "You are suffering from a transitory feeling; don't give way to it, for it will soon pass. If you obey it, if you give up this fine position, this honorable post exempt from trouble and rivalry, this seat of authority safe from attack, you will regret it later on without being able to recover it."

From Jalal al-Din Rumi, Maulana: A Shoemaker and the Unfaithful Wife of a Sufi Surprised by her Husband’s Unexpected Return Home

“Thus I remained, torn asunder by the opposite forces of earthly passions and religious aspirations, for about six months from the month Rajab of the year A.D. 1096. At the close of them my will yielded and I gave myself up to destiny. God caused an impediment to chain my tongue and prevented me from lecturing. Vainly I desired, in the interest of my pupils, to go on with my teaching, but my mouth became dumb. The silence to which I was condemned cast me into a violent despair; my stomach became weak; I lost all appetite; I could neither swallow a morsel of bread nor drink a drop of water. The enfeeblement of my physical powers was such that the doctors, despairing of saving me, said, "The mischief is in the heart, and has communicated itself to the whole organism; there is no hope unless the cause of his grievous sadness be arrested."

“Finally, conscious of my weakness and the prostration of my soul, I took refuge in God as a man at the end of himself and without resources. "He who hears the wretched when they cry" (Qur'an, xxvii. 63) deigned to hear me; He made easy to me the sacrifice of honors, wealth, and family. I gave out publicly that I intended to make the pilgrimage to Mecca, while I secretly resolved to go to Syria, not wishing that the Caliph (may God magnify him) or my friends should know my intention of settling in that country. I made all kinds of clever excuses for leaving Baghdad with the fixed intention of not returning thither. The Imams of Iraq criticized me with one accord. Not one of them could admit that this sacrifice had a religious motive, because they considered my position as the highest attainable in the religious community. "Behold how far their knowledge goes!" (Qur'an, liii. 31). All kinds of explanations of my conduct were forthcoming. Those who were outside the limits of Iraq attributed it to the fear with which the Government inspired me. Those who were on the spot and saw how the authorities wished to detain me, their displeasure at my resolution and my refusal of their request, said to themselves, "It is a calamity which one can only impute to a fate which has befallen the Faithful and Learning!"

“At last I left Baghdad, giving up all my fortune. Only, as lands and property in Iraq can afford an endowment for pious purposes, I obtained a legal authorization to preserve as much as was necessary for my support and that of my children; for there is surely nothing more lawful in the world than that a learned man should provide sufficient to support his family. I then betook myself to Syria, where I remained for two years, which I devoted to retirement, meditation, and devout exercises. I only thought of self-improvement and discipline and of purification of the heart by prayer in going through the forms of devotion which the Sufis had taught me. I used to live a solitary life in the Mosque of Damascus, and was in the habit of spending my days on the minaret after closing the door behind me.

Jalal al-Din Rumi, Maulana: A Wise Man and a Peacock Plucking Out its Feathers Not to be Attractive to People

“From thence I proceeded to Jerusalem, and every day secluded myself in the Sanctuary of the Rock. After that I felt a desire to accomplish the pilgrimage, and to receive a full effusion of grace by visiting Mecca, Medina, and the tomb of the Prophet. After visiting the shrine of the Friend of God (Abraham), I went to the Hedjaz. Finally, the longings of my heart and the prayers of my children brought me back to my country, although I was so firmly resolved at first never to revisit it. At any rate I meant, if I did return, to live there solitary and in religious meditation; but events, family cares, and vicissitudes of life changed my resolutions and troubled my meditative calm. However irregular the intervals which I could give to devotional ecstasy, my confidence in it did not diminish; and the more I was diverted by hindrances, the more steadfastly I returned to it.

“Ten years passed in this manner. During my successive periods of meditation there were revealed to me things impossible to recount. All that I shall say for the edification of the reader is this: I learned from a sure source that the Sufis are the true pioneers on the path of God; that there is nothing more beautiful than their life, nor more praiseworthy than their rule of conduct, nor purer than their morality. The intelligence of thinkers, the wisdom of philosophers, the knowledge of the most learned doctors of the law would in vain combine their efforts in order to modify or improve their doctrine and morals; it would be impossible. With the Sufis, repose and movement, exterior or interior, are illumined with the light which proceeds from the Central Radiance of Inspiration. And what other light could shine on the face of the earth? In a word, what can one criticize in them? To purge the heart of all that does not belong to God is the first step in their cathartic method. The drawing up of the heart by prayer is the key-stone of it, as the cry "Allahu Akbar' (God is great) is the key-stone of prayer, and the last stage is the being lost in God. I say the last stage, with reference to what may be reached by an effort of will; but, to tell the truth, it is only the first stage in the life of contemplation, the vestibule by which the initiated enter.

“From the time that they set out on this path, revelations commence for them. They come to see in the waking state angels and souls of prophets; they hear their voices and wise counsels. By means of this contemplation of heavenly forms and images they rise by degrees to heights which human language can not reach, which one can not even indicate without falling into great and inevitable errors. The degree of proximity to Deity which they attain is regarded by some as intermixture of being (haloul), by others as identification (ittihad), by others as intimate union (wasl). But all these expressions are wrong, as we have explained in our work entitled, "The Chief Aim."

Jalal al-Din Rumi, Maulana: An Unhappy Deer in the Company of Donkeys

Those who have reached that stage should confine themselves to repeating the verse—What I experience I shall not try to say; Call me happy, but ask me no more. In short, he who does not arrive at the intuition of these truths by means of ecstasy, knows only the name of inspiration. The miracles wrought by the saints are, in fact, merely the earliest forms of prophetic manifestation. Such was the state of the Apostle of God, when, before receiving his commission, he retired to Mount Hira to give himself up to such intensity of prayer and meditation that the Arabs said: "Muhammad is become enamored of God." This state, then, can be revealed to the initiated in ecstasy, and to him who is incapable of ecstasy, by obedience and attention, on condition that he frequents the society of Sufis till he arrives, so to speak, at an imitative initiation. Such is the faith which one can obtain by remaining among them, and intercourse with them is never painful.

“But even when we are deprived of the advantage of their society, we can comprehend the possibility of this state (revelation by means of ecstasy) by a chain of manifest proofs. We have explained this in the treatise entitled "Marvels of the Heart," which forms part of our work, 'The Revival of the Religious Sciences." The certitude derived from proofs is called "knowledge"; passing into the state we describe is called "transport"; believing the experience of others and oral transmission is "faith." Such are the three degrees of knowledge, as it is written, "The Lord will raise to different ranks those among you who have believed and those who have received knowledge from him" (Qur'an, lviii. 12).

“But behind those who believe comes a crowd of ignorant people who deny the reality of Sufism, hear discourses on it with incredulous irony, and treat as charlatans those who profess it. To this ignorant crowd the verse applies: "There are those among them who come to listen to thee, and when they leave thee, ask of those who have received knowledge, 'What has he just said?' These are they whose hearts God has sealed up with blindness and who only follow their passions. Among the number of convictions which I owe to the practice of the Sufi rule is the knowledge of the true nature of inspiration. This knowledge is of such great importance that I proceed to expound it in detail.

Life of Sufi Mystic

Islamic Biography: Rabiah ibn Kab: Here is the story of Rabiah told in his own words: "I was still quite young when the light of iman shone through me and my heart was opened to the teachings of Islam. And when my eyes beheld the Messenger of God, for the first time, I loved him with a love that possessed my entire being. I loved him to the exclusion of everyone else. One day I said to myself: 'Woe to you, Rabi'ah. Why don't you put yourself completely in the service of the Messenger of God, peace be on him. Go and suggest this to him. If he is pleased with you, you would find happiness in being near him. You will be successful through love for him and you will have the good fortune of obtaining the good in this world and the good in the next.' [Source: Islamic Biographyies at University of Pennsylvania, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

“This I did hoping that he would accept me in his service. He did not dash my hopes. He was pleased that I should be his servant. From that day, I lived in the shadow of the noble Prophet. I went with him wherever he went. I moved in his orbit whenever and wherever he turned. Whenever he cast a glance in my direction, I would leap to stand in his presence. Whenever he expressed a need, he would find me hurrying to fulfil it. I would serve him throughout the day. When the day was over and he had prayed Salat al-Isha and retired to his home, I would think about leaving. But I would soon say to myself: 'Where would you go, Rabi'ah? Perhaps you may be required to do something for the Prophet during the night.' So I would remain seated at his door and would not leave the threshold of his house. The Prophet would spend part of his night engaged in Salat. I would hear him reciting the opening chapter of the Quran and he would continue reciting sometimes for a third or a half of the night. I would become tired and leave or my eyes would get the better of me and I would fail asleep.

Jalal al-Din Rumi, Maulana: Misbehaving Students and their Supposedly Sick Teacher

“It was the habit of the Prophet, peace be on him, that if someone did him a good turn, he loved to repay that person with something more excellent. He wanted to do something for me too in return for my service to him. So one day he came up tome and said: 'O Rabi'ah ibn Kab.' 'Labbayk ya rasulullah wa Sadark - At your command, O Messenger of God and may God grant you happiness,' I responded. 'Ask of me anything and I will give it to you.' I thought a little and then said: 'Give me some time, O Messenger of God, to think about what I should ask of you. Then I will let you know.' He agreed.

“At that time, I was a young man and poor. I had neither family, nor wealth, nor place of abode. I used to shelter in the Suffah of the mosque with other poor Muslims like myself. People used to call us the "guests of Islam". Whenever any Muslim brought something in charity to the Prophet, he would send it all to us. And if someone gave him a gift he would take some of it and leave the rest for us. So, it occurred to me to ask the Prophet for some worldly good that would save me from poverty and make me like others who had wealth, wife and children. Soon, however, I said: 'May you perish Rabi'ah. The world is temporary and will pass away. You have your share of sustenance in it which God has guaranteed and which must come to you.

“The Prophet, peace be on him, has a place with his Lord and no request would be refused him. Request him therefore, to ask Allah to grant you something of the bounty of the hereafter.' I felt pleased and satisfied with this thought. I went to the Prophet and he asked: 'What do you say, O Rabi'ah?' 'O Messenger of God,' I said, 'I ask you to beseech God most High on my behalf to make me your companion in Paradise.' 'Who has advised you thus?' asked the Prophet. 'No by God,' I said, 'No one has advise me. But when you told me 'Ask of me anything and I will give to you,' I thought of asking you for something of the goodness of this world. But before long, I was guided to choose what is permanent and lasting against what is temporary and perishable. And so I have asked you to beseech God on my behalf that I may be your companion in Paradise.'

“The Prophet remained silent for a long while and then asked: 'Any other request besides that, Rabi'ah?' 'No, O Messenger of God, Nothing can match what I have asked you.' 'Then, in that case, assist me for your sake by performing much prostration to God.' So I began to exert myself in worship in order to attain the good fortune of being with the Prophet in Paradise just as I had the good fortune of being in his service and being his companion in this world. Not long afterwards, the Prophet called me and asked: 'Don't you want to get married, Rabi'ah?' 'I do not want anything to distract me from your service,' I replied. 'Moreover, I don't have anything to give as mahr (dowry) to a wife nor any place where I can accommodate a wife.'

Jalal al-Din Rumi, Maulana: Townspeople, Who have Never Seen an Elephant, Examine its Appearance in the Dark

“The Prophet remained silent. When he saw me again he asked: 'Don't you want to get married, Rabi'ah?' I gave him the same reply as before. Left to myself again, I regretted what I had said and chided myself: 'Woe to you, Rabi'ah. By God, the Prophet knows better than you what is good for you in this world and the next and he also knows better than you what you possess. By God, if the Prophet, peace be on him, should ask me again to marry, I would reply positively.' Before long, the Prophet asked me again: 'Don't you want to get married 'Rabi'ah?' 'Oh yes, Messenger of God,' I replied, 'but who will marry me when I am in the state you know.' 'Go to the family of so-and-so and say to them: the Prophet has instructed you to give your daughter in marriage to me.' Timidly, I went to the family and said: 'The Messenger of God, peace be on him, has sent me to you to ask you to give your daughter in marriage to me.' 'Our daughter?' they asked, incredulously at first. 'Yes,' i replied. 'Welcome to the Messenger of God, and welcome to his messenger. By God, the messenger of God's Messenger shall only return with his mission fulfilled. 'So they made a marriage contract between me and her. I went back to the Prophet and reported: 'O Messenger of Allah. I have come from the best of homes. They believed me, they welcomed me, and they made a marriage contract between me and their daughter. But from where do I get the mahr for her?'

“The Prophet then sent for Buraydah ibn al-Khasib, one of the leading persons in my tribe, the Banu Asiam, and said to him: 'O Buraydah, collect a nuwat's weight in gold for Rabi'ah. This they did and the Prophet said to me: 'Take this to them and say, this is the sadaq of your daughter.' I did so and they accepted it. They were pleased and said, This is much and good.' I went back to the Prophet and told him: 'I have never yet seen a people more generous than they. They were pleased with what I gave them in spite of its being little...Where can I get something for the walimah (marriage feast), O Prophet of God?' The Prophet said to Buraydah 'Collect the price of a ram for Rabi'ah.' They bought a big fat ram for me and then the Prophet told me: 'Go to Aishah and tell her to give you whatever barley she has.'

“Aishah gave me a bag with seven saas of barley and said: 'By God, we do not have any other food.' I set off with the ram and the barley to my wife's family. They said: 'We will prepare the barley but get your friends to prepare the ram for you.' We slaughtered, skinned and cooked the ram. So we had bread and meat for the walimah. I invited the Prophet and he accepted my invitation. The Prophet then gave me a piece of land near Abu Bakr's. From then I became concerned with the dunya, with material things. I had a dispute with Abu Bakr over a palm tree. 'It is in my land,' I insisted. 'No, it is in my land,' Abu Bakr countered. We started to argue. Abu Bakr cursed me, but as soon as he had uttered the offending word. he felt sorry and said to me: 'Rabiah, say the same word to me so that it could be considered as qisas -just retaliation.' 'No by God, I shall not,' I said. 'In that case, replied Abu Bakr. 'I shall go the Messenger of God and complain to him about your refusal to retaliate against me measure for measure.'

“He set off and I followed him. My tribe, the Banu Asiam, also set off behind me protesting indignantly: 'He's the one who cursed you first and then he goes off to the Prophet before you to complain about you!' I turned to them and said: 'Woe to you! Do you know who this is? This is As-Siddiq... and he is the respected elder of the Muslims. Go back before he turns around, sees you and thinks that you have come to help me against him. He would then be more incensed and go to the Prophet in anger. The Prophet would get angry on his account. Then Allah would be angry on their account and Rabi'ah would be finished.' They turned back. Abu Bakr went to the Prophet and related the incident as it had happened. The Prophet raised his head and said to me: 'O Rabi'ah, what's wrong with you and as-Siddiq?' 'Messenger of God, he wanted me to say the same words to him as he had said to me and I did not.' 'Yes, don't say the same word to him as he had said to you. Instead say: 'May God forgive you Abu Bakr.' With tears in his eyes, Abu Bakr went away while saying: 'May God reward you with goodness for my sake, O Rabiah ibn Kab... 'May God reward you with goodness for my sake, O Rabiah ibn Kaab..."”

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; "Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959)

Last updated April 2024