SUFI SAINTS

Holy graves of Khwaja Wali Sufism encourages rather than discourages the worship of religious leaders. Sufi saints are believed to have performed miracles, broken the laws of nature and cured illnesses. Some were executed because their beliefs were regarded as heretical by mainstream Muslims. The graves of Sufi saints are sought by pilgrims.

Many Sufi orders and school are associated with famous Sufi saints and mystics, which include al-Hallaj (d. 922), who was executed while in an ecstatic state, and shouting “I am the Truth”; Abu Hamid al-Ghazali (d. 1111), the famous Sufi poet and philosopher; and Muhyi al-Din Ibn “Arabi (d. 1240) who preached that all beings are unified under Allah.

Sufi saints are chosen more or less by popular acclaim. One of the most important Sufi figures in Central Asia is Bakhautdin Naqshband, a 14th century woodcarver and He was the founder of the Naqshbandi sect. He stressed the importance of work and good deeds in living a full spiritual life.

Among Sufis, Muhammad is regarded as the greatest saint and has been viewed in terms similar to a Jewish or Christian Messiah. Sufis developed a mystical cult of the Prophet linked with the Qur’anic thesis of the “Covenant.” Adherents to this concept believe a cosmic link was made between Muhammad and God and Creation when Muhammad took on his role as a human intermediary between God and humanity. One Sufi text reads: “All the lights of the Prophets proceeded from his light; he was before all, his name was the first in the Book of Fate; he was known before all things and all beings, and will endure after the end of all.”

Websites on Sufis Divisions in Islam archive.org ; Sufism in the Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World williamcchittick.com ; Sufism, Sufis, and Sufi Orders – Sufism's Many Paths islam.uga.edu/Sufism ; The Threshold Society sufism.org ; Mysticism in Arabic and Islamic Philosophy, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy plato.stanford.edu ; Risala Roohi Sharif, translations (English and Urdu) of "The Book of Soul", by Hazrat Sultan Bahu, a 17th century Sufi risala-roohi.tripod.com; Sufism - an Inquiry sufismjournal.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Hidden Caliphate: Sufi Saints beyond the Oxus and Indus” by Waleed Ziad Amazon.com ;

“Winds of Grace: Poetry, Stories and Teachings of Sufi Mystics and Saints”

by Vraje Abramian Amazon.com ;

“Essential Sufism” by James Fadiman, Huston Smith, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Garden of Truth: The Vision and Promise of Sufism, Islam's Mystical Tradition” by Seyyed Hossein Nasr Amazon.com ;

“Living Presence (Revised): The Sufi Path to Mindfulness and the Essential Self”

by Kabir Edmund Helminski, Iman Amazon.com ;

“The Principles of Sufism” by ʿAʾishah al-Bauniyyah Amazon.com ;

“Women of Sufism: A Hidden Treasure” by Camille Adams Helminski Amazon.com ;

“Al-Ghazali's Path to Sufism: His Deliverance from Error” by Abu Hamid Muhammad al-Ghazali (Author) Amazon.com ;

“The Mysticism of Sound and Music: The Sufi Teaching of Hazrat Inayat Khan Amazon.com ;

“Sufi Music of India and Pakistan: Sound, Context, and Meaning” by Regula Burckhardt Qureshi Amazon.com

Sufi Miracles and Shrines

Bibi Jawindi's Tomb Sufi saints are said to have walked on water, turned themselves invisible, teletransported themselves to faraway places, produced objects out of thin air, ascertained the needs of troubled souls, sensed disasters and helped the sick by submitting themselves to Islam and praying so deeply they achieved a high level of spirituality. Many of the “karama” miracles performed by later Muslim saints and mystics, were performed by charismatic Muslim leaders associated with Sufism.

Hisham Muhammad Kabbani, a Sufi saint from the Naqshbandi order, told Newsweek that in 1971 he received an unexpected visit from his former master. He said the master told him, “I have received an inspiration from a chain of our grandmasters that your father is going to die tonight at 7 p.m.” Kabbanis said, How do you know this? My father is old but in good health?” The master replied, “It is through our essence and spiritual connection that has been passed on over thousands of years.”

Kabbani said it as around 5 in the evening when his master visited. He called his family together. At around five minutes before 7 the father began complaining of chest pains. By 7 he was dead from a heart attack.

Sufis are big on shrines built around the tombs of Sufi masters and saints. The can be inside mosques or stand alone. Pilgrims flow to the shrines to show their respect and wish for things by tying handkerchiefs to trees and making offerings similar to those made in Hindu and Buddhist rituals. Followers have claimed that miracles have occurred after visits to the shrines of dead Sufi saints. Some Sufis have stone platforms with carved stone plinths that are designed for Sufi prayers.

At sufi shrines, childless women pray for children, businessmen pray for success. Sometimes qawwali musicians perform. Special festivals are often held at the shrines on the saint’s birthday or other special days. Some are just local events. Others are big events that draw people from all over. Some have been the central events of major trade fairs and markets and have survived because the brought money to local people.

Sufi Love and Ecstacy

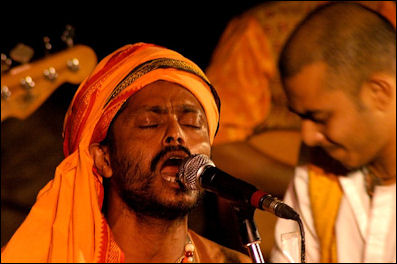

Ghousavi Shah at Masjid According to Sufism, the possession of moral disciple and absolute trust and obedience in God leads to intense ecstatic experiences similar to those achieved by Christians who speak in tongues and are filled with the holy spirit.

Sufi poets used expressions like “flooded with sweetness” and “intoxication” to describe their experiences. One 10th century Sufi wrote: “The love of God in its essence is the illumination of the heart by joy, because of its nearness to the Beloved; and when the heart is filled with that radiant joy, it finds its delight in being alone with the recollection of the Beloved, the joy of that intercourse overwhelms the mind, so that it is no longer concerned with this world and is therein.”

The Sufi writer and theologian Ibn Taymiya (1263-1328) wrote: "When the heart throbs with exhilaration and rapture becomes intense and the agitation of ecstasy is manifested and conventional forms are gone, that agitation is neither dancing nor bodily indulgence, but a dissolution of the soul.”

Sufi Mystical Discussions and Poetry

Sufi students debate questions like which did God create first the body or the soul and use logic and reason to examine things like the uncleanliness of monkeys and right of women to be religious leaders.

Dervish sessions are often accompanied by a discussion on mystical subjects led by a master. Describing such as session, Abercrombie wrote: The master "spoke slowly to my thought, lighting a cigarette in his long black holder. 'Is time real? Or merely an illusion, something man has fashioned to measure his progress in a timeless universe...In one's inner self, time takes a different form. Not flowing like a river but calm like a lake,' he said. 'Have you noticed, for instance, that in dreams, past, present, and future blend freely.'"

Sufism has inspired traditions and canons of literature and poetry in local languages. The verses often deal with the pain of separation from God and the great joy of reunion as expressed with romantic metaphors. The divine is often expressed as a man and the person seeking the union is expressed as a woman. Ecstacy is expressed as a merging of the two.

Dhikr: Sufi Ecstatic Techniques

Sufis have developed techniques to create ecstatic experiences and heighten them. Among them are the repetition of poems and holy names, music, dance, meditation, rhythmic beating, chanting and self hypnotism. The goal is to work oneself into a trance and loose contact with the immediate world to intensify one’s awareness of God. Ritual used to open a path to divine ecstacy are called “ dhikr”.

Sufis have developed techniques to create ecstatic experiences and heighten them. Among them are the repetition of poems and holy names, music, dance, meditation, rhythmic beating, chanting and self hypnotism. The goal is to work oneself into a trance and loose contact with the immediate world to intensify one’s awareness of God. Ritual used to open a path to divine ecstacy are called “ dhikr”.

According to the BBC: “Sufis are distinctive in nurturing theirs and others' spiritual dimension. They are aware that one of the names of the Prophet was Dhikr Allah (Remembrance of God). Dhikr as practised by Sufis is the invocation of Allah's divine names, verses from the Qur'an, or sayings of the Prophet in order to glorify Allah. Dhikr is encouraged either individually or in groups and is a source of tranquillity for Sufis. Many Sufis have used the metaphor of lovers to describe the state Dhikr leaves them in. Sufis say adherence to the Sharia manifests in the limbs and Dhikr manifests in the heart with the result that the outward is sober, the inner is drunk on divine love.” “Hearts become tranquil through the remembrance of Allah” — Qur'an 13:28 [Source: BBC, September 8, 2009 |::|]

Describing a Sufi sect in Egypt, Thomas Abercrombie wrote in National Geographic, "Devotees from the poorer quarters gather under colored lights to the cadent spell of flutes and drums. Wearing agate prayer beads and a red fez wrapped with a green turban, the tall, clean-shaven master led the emotional “dhikr” , a “memorial service to God,” waving the rhythm with a gilded baton."

" “Allah! Allah! Allah!” " the chant continued for half an hour, with hypnotic effect, then veered from prayer to poetry:

“

Stranger in this world

Shepherding the night starts

Sleepless, forlorn....”

Emotions flowed. before the evening was over I saw women swoon, grown men break into tears."

One Sufi technique involves repeating, “There is no god but God!” to a prescribed breathing and chest-beating sequence. Some techniques involve chains and are not that different from Shia Ashura rituals. Others employ hashish or other drugs, In India, Sufis use techniques like those used by Hindu holymen and yogis. Sufi mystics are sometimes called fakirs.

Sufis sometimes thrust knives into their cheeks and swallow burning torches like Hindu sadhus. In technique participants purportedly go into such a deep trance they can pass heated skewers through their cheeks without experiencing any pain. Sometimes the experiences are said to be so intense that initiates were warned not to embark on the journey to learn them unless they have a skilled master or sheik to guide them.

Sufi Music

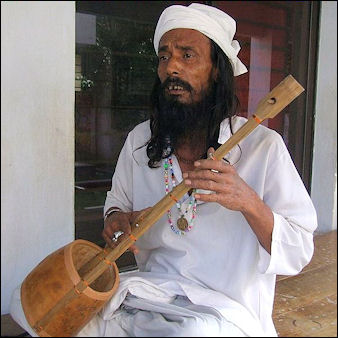

Parvati Baul The union of the body, spirit and music lies at the heart of Sufism. Sufis believe: "Music is the food of the spirit; when the spirit receives food, it turns aside from the government of the body." Sufis are credited with keeping the spirit of music alive in the Muslim world while orthodox Muslims tried to stamp it out. Sufis traditionally criticized those who criticized music.

According to 9th-century Baghdad philosopher Abu Suliman al-Darani Sufis believe that "music and singing do not produce in it that which is not in it" and music "reminds the spirit of the realm for which it constantly longs."

Sufi spiritual music is often highly-syncopated and hypnotic. One Sufi dancer said, "The music takes you over completely. It's a healing thing."

Some Sufi songs are popular villages songs about love with lyrics changed so the Muhammad is the object of love rather than a woman or a man. One songs goes, "It is he, it is only he who lives in my heart, only he whom I give my love, our beautiful Prophet Muhammad, whose eyes are made-up with kohl,"

See Separate Article SUFI MUSIC, DANCE AND FESTIVALS factsanddetails.com

Sufi Festivals

Fixtures of Sufism include secret recitations and annual 40-day retreats known as “ chilla” . Sufi “ mulids” , religious festivals that honor the saints of mosque, sometimes attracts hundreds of thousands of people even though they are denounced as "heretical" by orthodox Muslims. Members of Sufi clans often walk to the festival from their home villages, carrying banners and flags. Groups of musicians make their living by traveling from one mulid to another.

Describing a Sufi ritual at such a festival David Lodge wrote in the Rough Guide to World Music: "To a binding hypnotic rhythm, heaving movements and respiratory groans, the leader conducts the congregation by reciting Sufi poetry, guiding them from one maqam mode to another. Bodies sway, head roll upwards on every stroke as they chant religious devotions with spiraling intensity."

Sufi Dancing

Baul Ektara player Nicholas Schmidle wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “I stood at the edge of the courtyard and asked a young man named Abbas to explain this dancing, called dhamaal. Though dancing is central to the Islamic tradition known as Sufism, dhamaal is particular to some South Asian Sufis. "When a djinn infects a human body," Abbas said, referring to one of the spirits that populate Islamic belief (and known in the West as "genies"), "the only way we can get rid of it is by coming here to do dhamaal." A woman stumbled toward us with her eyes closed and passed out at our feet. Abbas didn't seem to notice, so I pretended not to either. [Source: Nicholas Schmidle, Smithsonian Magazine, December 2008 |+|]

“"What goes through your head when you are doing dhamaal?" I asked. "Nothing. I don't think," he said. A few women rushed in our direction, emptied a water bottle on the semiconscious woman's face and slapped her cheeks. She shot upright and danced back into the crowd. Abbas smiled. "During dhamaal, I just feel the blessings of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar wash over me."” |+|

See Separate Article SUFI MUSIC, DANCE AND FESTIVALS factsanddetails.com

Pirs in South Asia

A Pir or Peer is a title for a Sufi spiritual guide. A Pir's role is to guide and instruct his disciples on the Sufi path. This is often done by general lessons (called Suhbas) and individual guidance. Other words that refer to a Pir include Murshid The path of Sufism starts when a student takes an oath of allegiance with a teacher called Bai'at or Bay'ah where he swears allegiance at the hands of his Pir and repents of all his previous sins. After that, the student is called a Murid. From here, his batin (esoteric) journey starts. [Source: Wikipedia]

Baul of the group Oikyotaan In South Asia, the term pir is more commonly used and combines the meanings of teacher and saint. In Islam there has been a perennial tension between the ulama — Muslim scholars — and the Sufis; each group advocates its method as the preferred path to salvation. There also have been periodic efforts to reconcile the two approaches. Throughout the centuries many gifted scholars and numerous poets have been inspired by Sufi ideas even though they were not actually adherents. [Source: James Heitzman and Robert Worden, Library of Congress, 1989 *]

Pirs do not attain their office through consensus and do not normally function as community representatives. The villager may expect a pir to advise him and offer inspiration but would not expect him to lead communal prayers or deliver the weekly sermon at the local mosque. Some pirs, however, are known to have taken an active interest in politics either by running for public office or by supporting other candidates.

Saints, Brotherhoods and Sufism in North Africa

Islam as practiced in North Africa is interlaced with indigenous Berber beliefs. Although the orthodox faith preached the unique and inimitable majesty and sanctity of God and the equality of God's believers, an important element of North African Islam for centuries has been a belief in the coalescence of special spiritual power in particular living human beings. The power is known as baraka, a transferable quality of personal blessedness and spiritual force said to lodge in certain individuals. Those whose claim to possess baraka can be substantiated--through performance of apparent miracles, exemplary human insight, or genealogical connection with a recognized possessor--are viewed as saints. These persons are known in the West as marabouts, a French transliteration of al murabitun (those who have made a religious retreat), and the benefits of their baraka are believed to accrue to those ordinary people who come in contact with them. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Libya: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1987*]

Sufis in Egypt

The cult of saints became widespread in rural areas; in urban localities, Islam in its orthodox form continued to prevail. Saints were present in Tripolitania, but they were particularly numerous in Cyrenaica. Their baraka continued to reside in their tombs after their deaths. The number of venerated tombs varied from tribe to tribe, although there tended to be fewer among the camel herders of the desert than among the sedentary and nomadic tribes of the plateau area. In one village, a visitor in the late 1960s counted sixteen still-venerated tombs.*

Coteries of disciples frequently clustered around particular saints, especially those who preached an original tariqa (devotional "way"). Brotherhoods of the followers of such mystical teachers appeared in North Africa at least as early as the eleventh century and in some cases became mass movements. The founder ruled an order of followers, who were organized under the frequently absolute authority of a leader, or shaykh. The brotherhood was centered on a zawiya (pl., zawaya.*

Because of Islam's austere rational and intellectual qualities, many people have felt drawn toward the more emotional and personal ways of knowing God practiced by mystical Islam, or Sufism. Found in many parts of the Muslim world, Sufism endeavored to produce a personal experience of the divine through mystic and ascetic discipline. Sufi adherents gathered into brotherhoods, and Sufi cults became extremely popular, particularly in rural areas. Sufi brotherhoods exercised great influence and ultimately played an important part in the religious revival that swept through North Africa during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In Libya, when the Ottoman Empire proved unable to mount effective resistance to the encroachment of Christian missionaries, the work was taken over by Sufi-inspired revivalist movements. Among these, the most forceful and effective was that of the Sanusis, which extended into numerous parts of North Africa.*

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, Encyclopedia.com, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, Al Jazeera, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Library of Congress and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024