Home | Category: Muslim Groups / Shiites

TWELVER SHIA

Twelve Imam of Shia Islam circled around Muhammad

Of the several Shia sects, the Twelve Imam or Twelver (ithna- ashari), is dominant in Iran; most Shia in Bahrain, Iraq, and Lebanon also follow this sect. All the Shia sects originated among early Muslim dissenters in the first three centuries following the death of the Prophet Muhammad in A.D. 632. [Source: Library of Congress, December 1987 *]

The principal belief of Twelvers, but not of other Shia, is that the spiritual and temporal leadership of the Muslim community passed from Muhammad to Ali and then sequentially to eleven of Ali's direct male descendants, a tenet rejected by Sunnis. Over the centuries various other theological differences have developed between Twelver Shia and Sunnis.

Twelver Shia Muslims believe in five basic principles of faith: there is one God, who is a unitary divine being in contrast to the trinitarian being of Christians; the Prophet Muhammad is the last of a line of prophets beginning with Abraham and including Moses and Jesus, and he was chosen by God to present His message to mankind; there is a resurrection of the body and soul on the last or judgment day; divine justice will reward or punish believers based on actions undertaken through their own free will; and Twelve Imams were successors to Muhammad. The first three of these beliefs are also shared by non- Twelver Shia and Sunni Muslims. [Source: Library of Congress]

Websites on Shia Muslims (Shiites) Divisions in Islam archive.org ; Shi’a History and Identity shiism.wcfia.harvard.edu ; What is Shi'a Islam? iis.ac.uk ; History of Shi'ism: From the Advent of Islam up to the End of Minor Occultation al-islam.org ; Shafaqna: International Shia News Agency shafaqna.com ; Roshd.org, a Shia Website roshd.org/eng ; The Shiapedia, an online Shia encyclopedia web.archive.org ; Imam Al-Khoei Foundation (Twelver) al-khoei.org ; Official Website of Nizari Ismaili (Ismaili) the.ismaili ; Official Website of Alavi Bohra (Ismaili) alavibohra.org ; The Institute of Ismaili Studies (Ismaili) web.archive.org ; Four Sunni Schools of Thought masud.co.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Twelver Shiism: Unity and Diversity in the Life of Islam, 632 to 1722" by Andrew J. Newman Amazon.com ;

“The Formative Period of Twelver Shi'ism: Hadith as Discourse Between Qum and Baghdad’

by Andrew J. Newman Amazon.com ;

“Doctrines of the Twelver Shiite” by Abdurrahman bin Sa’d bin Ali Al-Shathri Amazon.com ;

Amazon.com ;

“An Introduction to Shia Islam: Belief system, leadership and history” by Den Väntades Vänner Amazon.com ;

“Shi'i Islam: An Introduction (Introduction to Religion) Amazon.com ;

An Introduction to Shi`i Islam: The History and Doctrines of Twelver Shi'ism

by Moojan Momen Amazon.com ;

“Shia'ism From Qur'an” by Sayed Jawad Zaidi Amazon.com ;

“The Caliph and the Imam: The Making of Sunnism and Shiism” by Toby Matthiesen Amazon.com ;

“Sunnis and Shi'a: A Political History” by Laurence Louër and Ethan Rundell Amazon.com ;

“After the Prophet: The Epic Story of the Shia-Sunni Split in Islam” by Lesley Hazleton and Blackstone Amazon.com ;

“The Prophet's Heir: The Life of Ali ibn Abi Talib” by Hassan Abbas Amazon.com ;

“The Sayings and Wisdom of Imam Ali” by Shaykh Fadhlalla Haeri, Asadullah Ad-Dhakir Yate Amazon.com ;

“The Virtues of Ali ibn Abi Talib”

by Luqman Al-Andalusi Amazon.com ;

“Ali Ibn Al-Husayn: A Critical Biography” by Abdullah Al-Rabbat Amazon.com ;

“Husayn: The Saga of Hope” by Jalal Moughania Amazon.com ;

“A Historical Research on the Lives of the 12 Shia Imams” by Dr. Mahdi Maghrebi Amazon.com ;

“The Shia Revival” by Vali Nasr Amazon.com ;

“The Shia: Identity. Persecution. Horizons” by Riyadh Al-Hakeem , Elvana Hammoud, et al. Amazon.com

Twelver Shia Imamate

The Twelver Shia believe that the Twelve Imams who succeeded the Prophet were sinless and free from error and had been chosen by God through Muhammad. The Twelfth Imam is believed to have ascended into a supernatural state to return to earth on judgment day. [Source: Library of Congress *]

None of the Twelve Imams, with the exception of Ali, ever ruled an Islamic government. During their lifetimes, their followers hoped that they would assume the rulership of the Islamic community, a rule that was believed to have been wrongfully usurped. Because the Sunni caliphs were cognizant of this hope, the Imams generally were persecuted during the Umayyad and Abbasid dynasties. Therefore, the Imams tried to be as unobtrusive as possible and to live as far as was reasonable from the successive capitals of the Islamic empire.*

The sixth imam Jafar as-Sadiq (d. 769) urged Shia to withdraw from politics. The seventh imam is his second son Musa al-Kazim, The eight Imam Al-Rida was named to be Caliph but died in 818, possibly from murder before he could take the position. The 10th imam, Ali al-Hadi was imprisoned in 848 in Samarra, Iraq and died in 868. His son, Hasan al-Askari, the 11th Imam, lived and died in the same prison after his death. He is known as the Hidden Imam.

Eighth Imam, Reza

Imam Rez Shrine in Mashhad, Iran

During the ninth century Caliph Al Mamun, son of Caliph Harun ar Rashid, was favorably disposed toward the descendants of Ali and their followers. He invited the Eighth Imam, Reza (A.D. 765-816), to come from Medina to his court at Marv (Mary in the present-day Soviet Union). While Reza was residing at Marv, Mamun designated him as his successor in an apparent effort to avoid conflict among Muslims. Reza's sister Fatima journeyed from Medina to be with her brother but took ill and died at Qom. A shrine developed around her tomb, and over the centuries Qom has become a major Shia pilgrimage and theology center. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Mamun took Reza on his military campaign to retake Baghdad from political rivals. On this trip Reza died unexpectedly in Khorasan. Reza was the only Imam to reside or die in what is now Iran. A major shrine, and eventually the city of Mashhad, grew up around his tomb, which has become the most important pilgrimage center in Iran. Several important theological schools are located in Mashhad, associated with the shrine of the Eighth Imam.*

Reza's sudden death was a shock to his followers, many of whom believed that Mamun, out of jealousy for Reza's increasing popularity, had him poisoned. Mamun's suspected treachery against Reza and his family tended to reinforce a feeling already prevalent among his followers that the Sunni rulers were untrustworthy.*

Twelfth Imam

The Twelfth Imam is believed to have been only five years old when the Imamate descended upon him in A.D. 874 at the death of his father. The Twelfth Imam is usually known by his titles of Imam-e Asr (the Imam of the Age) and Sahib az Zaman (the Lord of Time). Because his followers feared he might be assassinated, the Twelfth Imam was hidden from public view and was seen only by a few of his closest deputies. Sunnis claim that he never existed or that he died while still a child. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Shia believe that the Twelfth Imam remained on earth, but hidden from the public, for about seventy years, a period they refer to as the lesser occultation (gheybat-e sughra). Shia also believe that the Twelfth Imam has never died, but disappeared from earth in about A.D. 939. Since that time the greater occultation (gheybat-e kubra) of the Twelfth Imam has been in force and will last until God commands the Twelfth Imam to manifest himself on earth again as the Mahdi, or Messiah. Shia believe that during the greater occultation of the Twelfth Imam he is spiritually present — some believe that he is materially present as well — and he is besought to reappear in various invocations and prayers. His name is mentioned in wedding invitations, and his birthday is one of the most jubilant of all Shia religious observances.*

Shia Religious Institutions and Organizations in Iran

Historically, the single most important religious institution in Iran has been the mosque. In towns, congregational prayers, as well as prayers and rites associated with religious observances and important phases in the lives of Muslims, took place in mosques. Iranian Shia before the Revolution did not generally attach great significance to institutionalization, however, and there was little emphasis on mosque attendance, even for the Friday congregational prayers. Mosques were primarily an urban phenomenon, and in most of the thousands of small villages there were no mosques. Mosques in the larger cities began to assume more important social roles during the 1970s; during the Revolution they played a prominent role in organizing people for the large demonstrations that took place in 1978 and 1979. Since that time their role has continued to expand, so that in 1987 mosques played important political and social roles as well as religious ones. [Source: Library of Congress, December 1987 *]

Another religious institution of major significance was a special building known as a hoseiniyeh. Hoseiniyehs existed in urban areas and traditionally served as sites for recitals commemorating the martyrdom of Husayn, especially during the month of Moharram. In the 1970s, some hoseiniyehs, such as the Hoseiniyeh Irshad in Tehran, became politicized as prominent clerical and lay preachers used the symbol of the deaths as martyrs of Husayn and the other Imams as thinly veiled criticism of Mohammad Reza Shah's regime, thus helping to lay the groundwork for the Revolution in 1979.*

Jamkaran Mosque in Qom Iran is a popular pilgrimage site for Shia Muslims, many of whom believe that the Twelfth Imam (Muhammad al-Mahdi) — a messiah figure Shia believe will lead the world to an era of universal peace — once appeared and offered prayers at Jamkaran

A traditional source of financial support for all religious institutions has been the vaqf, a religious endowment by which land and other income-producing property is given in perpetuity for the maintenance of a shrine, mosque, madraseh, or charitable institution such as a hospital, library, or orphanage. A mutavalli administers a vaqf in accordance with the stipulations in the donor's bequest. In many vaqfs the position of mutavalli is hereditary. Under the Pahlavis, the government attempted to exercise control over the administration of vaqfs, especially those of the larger shrines. This was a source of conflict with the clergy, who perceived the government's efforts as lessening their influence and authority in traditional religious matters.*

The government's interference with the administration of vaqfs led to a sharp decline in the number of vaqf bequests. Instead, wealthy and pious Shia chose to give financial contributions directly to the leading ayatollahs in the form of zakat, or obligatory alms. The clergy in turn used the funds to administer their madrasehs and to institute various educational and charitable programs, which indirectly provided them with more influence in society. The access of the clergy to a steady and independent source of funding was an important factor in their ability to resist state controls and ultimately helped them direct the opposition to the shah. *

Shia Madresehs in Iran

Institutions providing religious education include madrasehs and maktabs. Madrasehs, or seminaries, historically have been important for advanced training in Shia theology and jurisprudence. Madrasehs are generally associated with noted Shia scholars who have attained the rank of ayatollah. There are also some older madrasehs, established initially through endowments, at which several scholars may teach. Students, known as talabehs, live on the grounds of the madrasehs and are provided stipends for the duration of their studies, usually a minimum of seven years, during which they prepare for the examinations that qualify a seminary student to be a low-level preacher, or mullah. At the time of the Revolution, there were slightly more than 11,000 talabehs in Iran; approximately 60 percent of these were studying at the madrasehs in the city of Qom, another 25 percent were enrolled in the important madrasehs of Mashhad and Esfahan, and the rest were at madrasehs in Tabriz, Yazd, Shiraz, Tehran, Zanjan, and other cities. [Source: Library of Congress, December 1987 *]

Maktabs, primary schools run by the clergy, were the only educational institutions prior to the end of the nineteenth century when the first secular schools were established. Maktabs declined in numbers and importance as the government developed a national public school system beginning in the 1930s. Nevertheless, maktabs continued to exist as private religious schools right up to the Revolution. Since 1979 the public education system has been desecularized and the maktabs and their essentially religious curricula merged with government schools.*

madrasek in Kashan, Iran

Shia Shrines In Iran

Another major religious institution in Iran is the shrine. There are more than 1,100 shrines that vary from crumbling sites associated with local saints to the imposing shrines of Imam Reza and his sister Fatima in Mashhad and Qom, respectively. These more famous shrines are huge complexes that include the mausoleums of the venerated Eighth Imam and his sister, tombs of former shahs, mosques, madrasehs, and libraries. Imam Reza's shrine is the largest and is considered to be the holiest. In addition to the usual shrine accoutrements, Imam Reza's shrine contains hospitals, dispensaries, a museum, and several mosques located in a series of courtyards surrounding his tomb. Most of the present shrine dates from the early fourteenth century, except for the dome, which was rebuilt after being damaged in an earthquake in 1673. The shrine's endowments and gifts are the largest of all religious institutions in the country. Traditionally, free meals for as many as 1,000 people per day are provided at the shrine. Although there are no special times for visiting this or other shrines, it is customary for pilgrimage traffic to be heaviest during Shia holy periods. It has been estimated that more than 3 million pilgrims visit the shrine annually. [Source: Library of Congress, December 1987 *]

Visitors to Imam Reza's shrine represent all socioeconomic levels. Whereas piety is a motivation for many, others come to seek the spiritual grace or general good fortune that a visit to the shrine is believed to ensure. Commonly a pilgrimage is undertaken to petition Imam Reza to act as an intermediary between the pilgrim and God. Since the nineteenth century, it has been customary among the bazaar class and members of the lower classes to recognize those who have made a pilgrimage to Mashhad by prefixing their names with the title mashti.*

The next most important shrine is that of Imam Reza's sister, Fatima, known as Hazarat-e Masumeh (the Pure Saint). The present shrine dates from the early sixteenth century, although some later additions, including the gilded tiles, were affixed in the early nineteenth century. Other important shrines are those of Shah Abdol Azim, a relative of Imam Reza, who is entombed at Rey, near Tehran, and Shah Cheragh, a brother of Imam Reza, who is buried in Shiraz. A leading shrine honoring a person not belonging to the family of Imams is that of the Sufi master Sayyid Nimatollah Vali near Kerman. Shia make pilgrimages to these shrines and the hundreds of local imamzadehs to petition the saints to grant them special favors or to help them through a period of troubles.*

Because Shia believe that the holy Imams can intercede for the dead as well as for the living, cemeteries traditionally have been located adjacent to the most important shrines in both Iran and Iraq. Corpses were transported overland for burial in Karbala in southern Iraq until the practice was prohibited in the 1930s. Corpses are still shipped to Mashhad and Qom for burial in the shrine cemeteries of these cities.*

The constant movement of pilgrims from all over Iran to Mashhad and Qom has helped bind together a linguistically heterogeneous population. Pilgrims serve as major sources of information about conditions in different parts of the country and thus help to mitigate the parochialism of the regions.*

Hazarat-e Masumeh at night

Shia Religious Hierarchy In Iran

From the time that Twelver Shia Islam emerged as a distinct religious denomination in the early ninth century, its clergy, or ulama, have played a prominent role in the development of its scholarly and legal tradition; however, the development of a distinct hierarchy among the Shia clergy dates back only to the early nineteenth century. Since that time the highest religious authority has been vested in the mujtahids, scholars who by virtue of their erudition in the science of religion (the Quran, the traditions of Muhammad and the imams, jurisprudence, and theology) and their attested ability to decide points of religious conduct, act as leaders of their community in matters concerning the particulars of religious duties. Lay Shia and lesser members of the clergy who lack such proficiency are expected to follow mujtahids in all matters pertaining to religion, but each believer is free to follow any mujtahid he chooses. Since the mid-nineteenth century it has been common for several mujtahids concurrently to attain prominence and to attract large followings. During the twentieth century, such mujtahids have been accorded the title of ayatollah. Occasionally an ayatollah achieves almost universal authority among Shia and is given the title of ayatollah ol ozma, or grand ayatollah. Such authority was attained by as many as seven mujtahids simultaneously, including Ayatollah Khomeini, in the late 1970s. [Source: Library of Congress, December 1987 *]

To become a mujtahid, it is necessary to complete a rigorous and lengthy course of religious studies in one of the prestigious madrasehs of Qom or Mashhad in Iran or An Najaf in Iraq and to receive an authorization from a qualified mujtahid. Of equal importance is either the explicit or the tacit recognition of a cleric as a mujtahid by laymen and scholars in the Shia community. There is no set time for studying a particular subject, but serious preparation to become a mujtahid normally requires fifteen years to master the religious subjects deemed essential. It is uncommon for any student to attain the status of mujtahid before the age of thirty; more commonly students are between forty and fifty years old when they achieve this distinction.*

Most seminary students do not complete the full curriculum of studies to become mujtahids. Those who leave the madrasehs after completing the primary level can serve as prayer leaders, village mullahs, local shrine administrators, and other religious functionaries. Those who leave after completing the second level become preachers in town and city mosques. Students in the third level of study are those preparing to become mujtahids. The advanced students at this level are generally accorded the title of hojjatoleslam when they have completed all their studies.*

The Shia clergy in Iran wear a white turban and an aba, a loose, sleeveless brown cloak, open in front. A sayyid, who is a clergyman descended from Muhammad, wears a black turban and a black aba. *

Hazarat-e Masumeh

Sufism and Shia Islam in Iran

Shah Ismail, the founder of the Safavid dynasty, who established Twelver Shia Islam as the official religion of Iran at the beginning of the sixteenth century, was revered by his followers as a Sufi master. Sufism, or Islamic mysticism, has a long tradition in Iran. It developed there and in other areas of the Islamic empire during the ninth century among Muslims who believed that worldly pleasures distracted from true concern with the salvation of the soul. Sufis generally renounced materialism, which they believed supported and perpetuated political tyranny. Their name is derived from the Arabic word for wool, suf, and was applied to the early Sufis because of their habit of wearing rough wool next to their skin as a symbol of their asceticism. Over time a great variety of Sufi brotherhoods was formed, including several that were militaristic, such as the Safavid order, of which Ismail was the leader. [Source: Library of Congress, December 1987 *]

Although Sufis were associated with the early spread of Shia ideas in the country, once the Shia clergy had consolidated their authority over religion by the early seventeenth century, they tended to regard Sufis as deviant. At various periods during the past three centuries some Shia clergy have encouraged persecution of Sufis, but Sufi orders have continued to exist in Iran. During the Pahlavi period, some Sufi brotherhoods were revitalized. Some members of the secularized middle class were especially attracted to them, but the orders appear to have had little following among the lower classes. The largest Sufi order was the Nimatollahi, which had khanehgahs, or teaching centers, in several cities and even established new centers in foreign countries. Other important orders were the Dhahabi and Kharksar brotherhoods. Sufi brotherhoods such as the Naqshbandi and the Qadiri also existed among Sunni Muslims in Kordestan. There is no evidence of persecution of Sufis under the Republic, but the brotherhoods are regarded suspiciously and generally have kept a low profile.*

Shia Sects in Iran

Iran also contains Shia sects that many of the Twelver Shia clergy regard as heretical. One of these is the Ismaili, a sect that has several thousand adherents living primarily in northeastern Iran. The Ismailis, of whom there were once several different sects, trace their origins to the son of Ismail who predeceased his father, the Sixth Imam. The Ismailis were very numerous and active in Iran from the eleventh to the thirteenth century; they are known in history as the "Assassins" because of their practice of killing political opponents. The Mongols destroyed their center at Alamut in the Alborz Mountains in 1256. Subsequently, their living imams went into hiding from non-Ismailis. In the nineteenth century, their leader emerged in public as the Agha Khan and fled to British-controlled India, where he supervised the revitalization of the sect. The majority of the several million Ismailis in the 1980s live outside Iran. [Source: Library of Congress, December 1987 *]

Another Shia sect is the Ahl-e Haqq. Its adherents are concentrated in Lorestan, but small communities also are found in Kordestan and Mazandaran. The origins of the Ahl-e Haqq are believed to lie in one of the medieval politicized Sufi orders. The group has been persecuted sporadically by orthodox Shia. After the Revolution, some of the sect's leaders were imprisoned on the ground of religious deviance. *

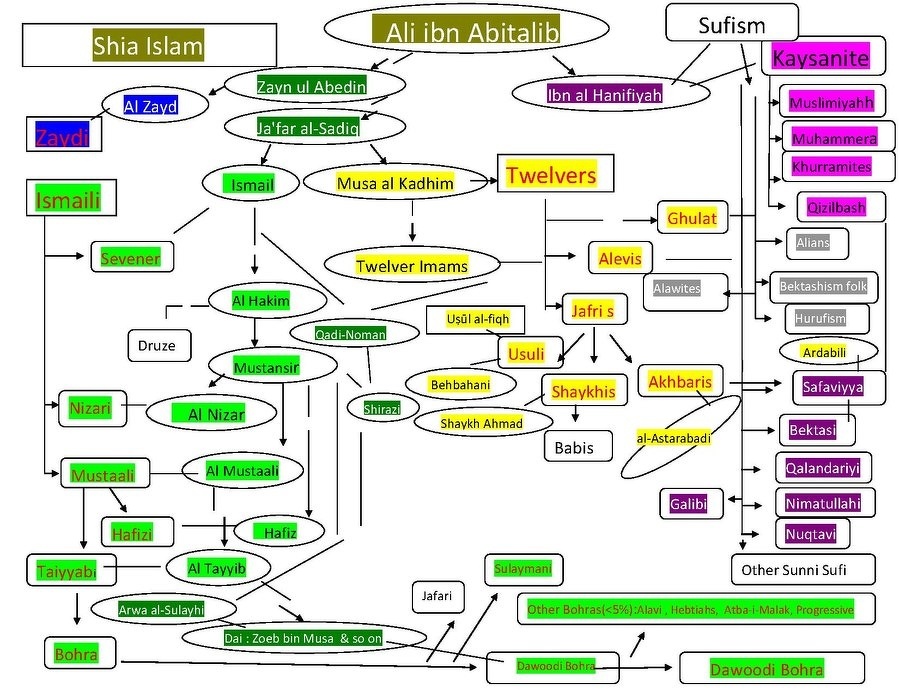

Shia imam and sects

Iraq Ayatollahs

The ayatollahs of the hawza in Najaf are the main religious authorities for Shia in Iraq. Jon Lee Anderson, The New Yorker, “The hawza is headed by four grand ayatollahs whose opinions are of enormous importance-particularly those of the paramount cleric, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani. "We are Shia, you know, and the Shia follow their leaders," one of Hakim's men had said to me when I was in Basra. "Even if Sayyid Abdulaziz wants to take a decision, he will first seek the opinion of Grand Ayatollah Sistani." Sistani issues his opinions in letters. He never speaks in public or talks to foreign officials or journalists, but he has delegated a few clerics to represent him.” [Source: Jon Lee Anderson, The New Yorker, February 2, 2004 ~]

The Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (ISCI or SIIC) is an Iraqi Shia Islamist Iraqi political party. It was known as the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI)). Anderson wrote in 2004, “sciri officials say that, while they are grateful to the Iranians for sheltering them and supporting them in the eighties and nineties, they are now independent of Tehran, and have scaled back their hopes for an Islamic revolution in Iraq. But Hakim certainly still has friendly links to Iran. In December, when he was the head of the Governing Council, he raised the issue of reparations for the Iran-Iraq War (Iran wants a hundred billion dollars), which he supports. Nevertheless, his proof of pragmatism and moderation is sciri's cooperation with the Coalition Provisional Authority. "If the Shia wanted to, they could burn down the whole Middle East," a former Jordanian intelligence officer said to me recently. "But they will do that only if they feel threatened."~

Abdulaziz al-Hakim, Iraqi The Shia Leader

Abdulaziz al-Hakim became the head of sciri after his brother Ayatollah Muhammad Bakr al-Hakim, was assassinated, in August, 2003. For a while it seemed as if he might be Iraq's president. He too was the target of assassinations — early December 2003, someone fired a rocket at him while he was visiting a mosque — and was useful to the Americans as they tried to bring peace and reign in sectarian violence in Iraq.

Jon Lee Anderson wrote in The New Yorker in 2004: “Hakim is married and has four children. When he returned to Iraq earlier this year, after two decades of exile in Iran, his family stayed in Qom, but they are with him now, in the Tariq Aziz house. His aides work downstairs, in austere rooms furnished with desks and chairs and not much else. The floor of one of the rooms is covered with a big carpet, and they sit on it and share meals, and then sleep on the carpet when their work is done. The upstairs rooms, where Hakim meets guests, are decorated in a style that is popular in Iraq. The carpets are faux Persian, the chairs are plush and thronelike, and the couches have baroquely carved gilt backs. I was taken to a room dominated by a large conference table, where Hakim was presiding over a sort of graduation ceremony for young people who had done well in a workshop called "Loyalty and Support."[Source: Jon Lee Anderson, The New Yorker, February 2, 2004 ~]

“Hakim, who was dressed in the black turban and gray robe of a Shia cleric, was at the head of the table, in front of a microphone, speaking to perhaps two dozen young Iraqi men and one woman. The woman was seated toward the back, in a chair pushed up against a wall. She appeared to be in her twenties, and wore a full-length skirt and a head scarf. Hakim was giving them a pep talk about how the Shia were at a juncture in history that was as important as the one they had experienced in 1920, after the Arab revolt against the British colonialists, which, he said, had led to a series of political decisions that determined the way Iraq has been ruled since then, and to the continued oppression of the Shia.~

Abdulaziz al-Hakim and Dick Cheney in 2008

“"People will be looking to you as their leaders," Hakim said to the earnest young Shia who had excelled in the course on loyalty. "We have already made a large step forward, with the establishment of the Governing Council"-the twenty-five-member Iraqi administrative body set up by the Coalition Provisional Authority last summer-"which my late brother Ayatollah Muhammad Bakr al-Hakim, may peace be upon him, approved. But it is now up to the rest of us to take the next steps, so that the democratic majority of Iraq"-i.e., the Shia-"can take their place in the society in which they have been treated as second-class citizens for nearly fourteen hundred years." He was counting from 661 A.D., when Ali, the Prophet Muhammad's son-in-law and, according to the Shia, his rightful successor, was assassinated. "It was the late Ayatollah's great wish that this be the case," Hakim said. Then everyone stood up, and Hakim handed out diplomas to the three top graduates. The first two were young men who inclined their heads to kiss his hand as he murmured words of praise. The third was the woman. She approached Hakim and prostrated herself on the floor at his feet. The men in the room clucked their tongues in disapproval at this display, and Hakim beckoned to her to rise. He handed her a diploma, but then she fell to the ground again, and the men in the room clucked their tongues again. She got up, her face flushed, and Hakim told her that she was an admirable example of Shia womanhood. He smiled, waved his arm in a salute, and he and his bodyguards swept out of the room.~

“The night after Hakim was interviewed on Al Arabiya, I returned to the villa. Hakim sat in an ornate chair in one of the garishly furnished rooms upstairs, and I sat in one just like it, next to him. We were served Turkish coffee, and a bodyguard brought Hakim a lighter and cigarettes. (He smokes when he is not in public.) He was wearing the same cheap, rubber-soled, black slip-on shoes he had been wearing the day before. Hakim is not personally vain. His vestments are elegant, but not luxurious, which is only proper for one who is a sayyid, a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, and the scion of one of Iraq's oldest and most highly regarded Shia clerical families. The Hakims have special status as a family of martyrs. The members of the family who remained in Iraq in the eighties were treated with particular brutality by Saddam, and more than fifty were murdered.~

“Abdulaziz al-Hakim speaks in a patient monotone, and he never displays anger or irritation in public. He seems more like a priest, or a judge, than like a politician, although his role has always been political. His father, who died in 1970, was involved in the uprising against the British in the nineteen-twenties and was the leading spiritual authority in Iraq in the sixties, the head of the hawza, or center of learning, in Najaf. Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani holds that position now. Abdulaziz's eldest brother was murdered in exile in Khartoum in 1988. The brother who was killed in August, Ayatollah Muhammad Bakr al-Hakim, was a religious scholar, although his decision to go to Iran, where he adopted Khomeini's brand of political Islam and sent his militia to fight against other Iraqis in the Iran-Iraq War, alienated many Iraqi Shia, including some of his fellow-clerics. Abdulaziz was his brother's closest political aide, and he commanded the Badr Brigade.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, Encyclopedia.com, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, Al Jazeera, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Library of Congress and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024