Home | Category: Modern History / 20th Century Middle Eastern and North African History

T.E. LAWRENCE

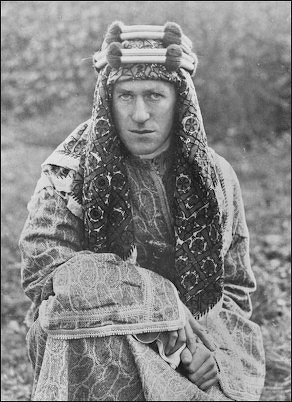

Lawrence in Arab clothes

Thomas Edward (T.E.) Lawrence, immortalized in the film “Lawrence of Arabia”, played a major role in the Arab revolt. But the extent of his role is of some debate but is clearly less than the film implies and what Lawrence wrote. Still he is largely regarded as an important historical figure. Churchill called him “one of the greatest beings alive in our time.” [Source: Don Belt, National Geographic, January 1999]

Lawrence (1888-1935) was an Oxford scholar, fluent in Arabic, who turned desert fighter. In World War I, Lawrence was a liaison officer, who worked under British General Allenby. In “Seven Pillars of Wisdom” Lawrence tells how he organized and equipped Bedouin warriors in their fight against the Turks.

According to his version of the story he thought up the strategy and kept the revolt going during its low moments. In “Seven Pillars of Wisdom”, Lawrence wrote: “I meant to make a new nation, to restore lost influence, to give twenty millions of Semites the foundations on which to build an inspired dream place of their national thoughts.” Arabs point out however that the revolt had already started when Lawrence came on board. Arab scholars says the results of the revolt would have been the same with or without the intrepid English adventurer.

Ben MacIntyre wrote in the New York Times: “His celebrity has sometimes obscured his real importance: he pioneered a new kind of “elastic” warfare; he was instrumental in the creation of three Middle Eastern kingdoms, including modern Iraq, in ways that have a direct bearing on the region’s turbulent politics today. In “Seven Pillars of Wisdom,” he produced one of the greatest lyrical depictions of war ever written.” [Source: Ben MacIntyre, New York Times, December 24, 2010 /*/]

Books: “Hero: The Life and Legend of Lawrence of Arabia” by Michael Korda, Harper/HarperCollins, 2010); “Lawrence, The Uncrowned King of Arabia” by Michael Asher (Overlook Press, 1999); “A Touch of Genius: The Life of T.E. Lawrence” by Malcolm Brown and Julia Cage (Paragon House, 1990). More than 50 biographies have been written about Lawrence.

Islamic History: Islamic History Resources uga.edu/islam/history ; Internet Islamic History Sourcebook fordham.edu/halsall/islam/islamsbook ; Islamic History friesian.com/islam ; Islamic Civilization cyberistan.org ; Muslim Heritage muslimheritage.com ; Brief history of Islam barkati.net ; Chronological history of Islam barkati.net

Lawrence of Arabia: Myths and Guises

Lawrence of Arabia was the largely creation of the American journalist Lowell Thomas, who was in the Middle East looking for a story and came across Lawrence dressed in Arab robes. He called Lawrence the “uncrowned King of Arabia” and wrote thrilling accounts of his exploits. A public tired of the blood and guts reports from World War I soaked it up. Lawrence himself was also accused of “massaging the truth.”

1918 painting of Lawrence

Ben MacIntyre wrote in the New York Times: “Lawrence was an ambiguous figure in his lifetime, and has remained so ever since, in part because the fog of fame made it virtually impossible to see him clearly, then and now. He was a scholar and warrior, an imperialist and supporter of Arab independence, a politician and rebel, a publicity seeker and recluse. Fighting alongside Arab irregulars in the revolt against Turkish Ottoman rule during World War I, he was fanatically brave and chillingly ruthless. He was fastidious, inconsistently vegetarian, sexually repressed, allergic to physical contact and addicted to danger, flagellation and roasting baths. He was fabulously weird. [Source:Ben MacIntyre, New York Times, December 24, 2010 /*/]

“Most treatments of Lawrence’s life can be divided into debunkings and hagiographies. “Hero” by Michael Korda, as the title implies, is closer to the latter category. The author’s admiration frequently comes in volleys: “physical courage, hardiness, cool judgment under fire,” “an outstanding shot, physically tireless, generous, absolutely fearless, gentle in manner.” Yet into this baggy but beguiling biography, Korda, the author of several works of history, has also crammed the darker incarnations of Lawrence, the shy depressive, the tortured ascetic, the “odd gnome, half cad — with a touch of genius,” in the words of one of his companions behind Turkish lines. This book, for all its worship of Lawrence, leaves the impression that his heroism lay in a unique brand of personal eccentricity, a refusal to fit into the expectations of others, an unshakable determination to do things his own way, however peculiar and wrong-headed this seemed.” /*/

“Lawrence was many men in many guises,” a “tense and fascinating contradiction, an amalgam of heroic strangeness. George Bernard Shaw, the friend and mentor whose name Lawrence would adopt in homage, once demanded of his enigmatic protégé, “What is your game, really?” Lawrence did not reply, perhaps because he did not really know the answer.”

T.E. Lawrence’s Early Life

Lawrence was born in Tremadoc, Wales and brought up outside of Oxford and was known as Ned in his youth. His parent were unmarried (his father was an aristocrat who left his wife and four daughters in Ireland for a governess, T.E.’s mother); he and his four brothers were illegitimate; and his family name was made up. Lawrence wasn’t made aware of these facts until he 10. He was also severely beaten by his domineering mother.

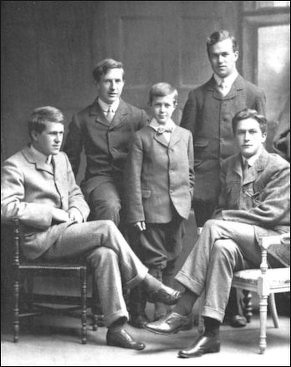

TE Lawrence, left, with his brothers

Ben MacIntyre wrote in the New York Times: “Lawrence was born in 1888, the illegitimate son of an Irish landowner who had scandalously run off with the family governess, Sarah Lawrence. They settled in Oxford, using her name — if it really was her name — as an alias (Lawrence would change his own name repeatedly in later life), where they brought up five sons, of whom Thomas Edward was the ―second-eldest, the cleverest and the oddest. Standing about 5 feet 5 inches tall, he had a long, mournful, equine face and piercing blue eyes. After his diminutive height, the eyes were the first aspect of his appearance to strike observers. His parents seem to have realized, and accepted, that this son would be different, and built him a cottage to live in at the bottom of their Oxford garden. [Source: Ben MacIntyre, New York Times, December 24, 2010]

Beginning when he was around eight or nine Lawrence began taking an interest in history and archeology, and was particularly interested in anything that had to do with the exotic East or The Crusades. He filled his room with pictures of knights and liked to forage through excavations looking for artifacts. He ate and slept very little and challenged himself with feats of endurance.

Lawrence attended Oxford on a scholarship and obtained a degree in history. It is said he ate little more than bread and water while was there. 1909, for his senior thesis on Crusader castles, he walked over one thousand miles (1,600 kilometers) through Palestine and Syria during the hottest months. Along the way he visited 36 castles, learned to speak good Arabic, traded shots with Bedouin tribesmen, suffered from attacks of malaria and was robbed and beaten and left for dead. After he earned a degree with honors from Oxford he worked as an archeologist on a Hittite site in Turkey

T.E. Lawrence’s Appearance and Character

Lawrence had blue eyes and chiseled handsome features. Unlike Peter O’ Toole, he was short, only five foot five. He had a soft voice and didn’t talk much. He loathed physical contact and often bowed instead of shaking hands. An Arab who fought at his side said he “was very clever, very tough, and expert with explosives” but added “he also had a bad, bad temper.” Many have described him as a masochist. One writer said he was a "vain, mercurial, moody, sensitive, pitiless. talented man.”

Lawrence sported Bedouin-style clothes and "took pleasure in flouting the rigid code of the spit-and-polish British army." He wore Arab robes during his famous desert campaign in the Arab Revolt. Explaining why, he wrote: “if you can wear Arab kit when with the tribes you will acquire their trust and intimacy to a degree impossible in uniform.”

Some scholars have suggested that T.E. Lawrence was gay. This is based partly on the close relationship he formed with a teenage water boy named Dahoum while he worked as an archeologist in Turkey and the fact that he never married and was never even engaged. In his writing he had little positive to say about heterosexuality but he described Arab-style homosexuality in general terms as “clean” “pure” and “sexless.” Dahoum is believed to been the object of the love poetry written by Lawrence.

Lawrence’s brother said all this was idle speculation. He insisted his brother died a virgin. Some scholars have reached the same conclusion. They say that he was probably homosexual by nature but because of his aversion to intimacy he never consummated it.

T.E. Lawrence in the Middle East

From December 1914 to October 1916, in the middle of World War I, Lawrence worked as a intelligence office in the British War office in Cairo. His coworkers regarded him as smart and irreverent, qualities which did not endear him with his superiors.

In October 1916, Lawrence arrived in Arabia as part of a secret mission to organize the Arab Revolt. He met with Sharif Hussein’s son Faisal, one of four brothers leading the Arab rebels.

Lawrence repeatedly wrote about his great admiration for the Arabs. For him they were like noble savages who, he wrote, were morally superior to Europeans because they were “primitive” and “innocent.” But ultimately he betrayed the Arabs, something which made him “continually and bitterly ashamed.”

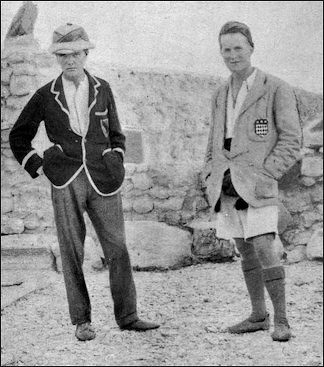

Lawrrence, left, with the famous Mesopotamian archaeologist Leonard Woolley

Ben MacIntyre wrote in the New York Times: “While studying architecture at Oxford, he toured the Crusader castles of Ottoman Syria, traveling more than 1,000 miles on foot, the first of many solitary, grueling journeys. On graduating, he returned to the Middle East as a field archaeologist. Gertrude Bell, the writer and political officer who would play a vital role in the creation of Iraq, found him in 1911 excavating the ancient city of Carchemish on the Syrian-Turkish border. Again, he made a remarkable sight, in Oxford college rowing blazer, white shorts, red Arab slippers curled up at the toes and a crimson woven belt with dangling tassels. [Source: Ben MacIntyre, New York Times, December 24, 2010 +++]

“Lawrence loved to dress up, but even when he had fully adopted the Bedouin outfit that became his trademark, he stood outside his adopted persona. “I could not sincerely take on the Arab skin: it was an affectation only.” With the outbreak of war, Lawrence’s knowledge of the Ottoman Empire ensured that he was posted to Cairo as an intelligence officer. In October 1916, he was sent to nurture the Arab revolt against Turkish rule, started by Sherif Hussein of Mecca... Lawrence swiftly became the key link between the British authorities and the rebels.” +++

Lowell Thomas and T.E. Lawrence

Ben MacIntyre wrote in the New York Times: “Lowell Thomas, the pioneering American journalist and filmmaker, was buying dates on a Jerusalem street soon after the holy city had been wrested from Turkish control by British forces in 1917, when he spotted a group of Arabs, led by a most remarkable figure. “A single Bedouin who stood out in sharp relief from his companions; . . . in his belt was fastened the short curved sword of a prince of Mecca, . . . marking him every inch a king. . . . This young man was blond as a Scandinavian. . . . His expression was serene, almost saintly, in its selflessness and repose.” [Source: Ben MacIntyre, New York Times, December 24, 2010 +++]

“The robed figure was T. E. Lawrence, Lawrence of Arabia, Laurens Bey to his Arab comrades in arms, the “Uncrowned King of Arabia” according to his boosters. And if Thomas’s description seems sensationalist, that is hardly surprising, for the American did more than any other single person to turn Lawrence into a glittering multimedia global celebrity, a fable, a saint and a myth. +++

“Though Lowell Thomas almost single-handedly created Lawrence of Arabia, the transformation of Lawrence into a romantic idol reached its apogee only in 1962 with the epic David Lean film starring Peter O’Toole. +++

T.E. Lawrence and the Arab Revolt

film poster

The Arab revolt against Turkish rule was started by Sherif Hussein of Mecca with the aim of creating a single Arab state stretching from Syria to Yemen. Lawrence called Hussein’s son Feisal “the leader who will bring the Arab Revolt to full glory” and described him as “very tall and pillar-like.” The two men formed a partnership with Lawrence acting as his assistant and a liaison between the British and the Arabs, and gave Feisal tips on being a charismatic leader necessary to unify and inspire the men under him.

In the early stages of the revolt, Lawrence led a small force of Bedouin fighters through the mountains of western Arabia to meet a larger force outside Medina. He fainted regularly and ran high fevers from dysentery. In the middle of the journey two Bedouins got into a fight and one man was killed. Realizing that a cycle of blood feuds was the last thing he needed he decided to take matters into his own hands, and kill the killer.

Lawrence wrote: “I made him rise and shot him through the chest. He fell down on the weeds shrieking, with blood coming out in spurts...I fired again, but was shaking so that I only broke his wrist” and then “shot him in the thick of the neck under the jaw.” Afterwards Lawrence was so shaken up he couldn’t get on his camel by himself.

Before a major offensive by the Arab forces against the Ottoman army, Lawrence asked the British government to lend him nine Rolls Royces for the attack. His request was granted and with the vehicles two enemy bridges were destroyed and two Turkish outposts were captured.

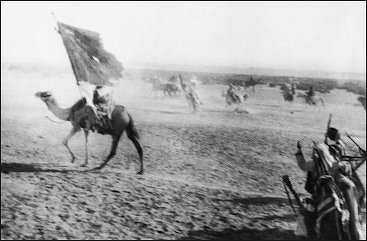

Ben MacIntyre wrote in the New York Times: “The Arab forces in 1916 were about as far from a conventional army as could be imagined, a fierce, unruly camel-―mounted collection of tribesman, with a strong inclination to feud, loot and desert. With British guns, sacks of gold sovereigns and Lawrence as their tactician, they would be molded into an effective guerrilla army.” [Source: Ben MacIntyre, New York Times, December 24, 2010]

Hejaz Railway

The campaign included “the harassment of Turkish communication lines, the ingenious sabotage, the astonishing forays by camel behind enemy lines through the harshest terrain and the almost medieval brutality of Arab methods (Lawrence killed his own wounded men rather than leave them to Turkish torture). The pukka Englishman in Arab dress developed highly successful tactics of hit and run, using a small, mobile force, in what would now be called asymmetrical warfare.

Lawrence of Arabia and Attacks on the Turkish Railroad

In March 1917, Lawrence’s group carried out their first attacks on the Hejaz Railway, which connected Medina with Damascus and was the main supply route for the Turks stationed in southern Arabia. Mounted on fast camels and aided by Lawrence, the highly mobile Arab blew up 79 bridges and an untold number of trains.

The railway line was key to keeping Turkish troops in Arabia supplied. Over the period of a year or so, Lawrence and his raiders "harassed the line, burning stations and blowing up trains, isolating the 10,000-man Turkish garrison. "Travel on the Hejaz Railway became so dangerous for those riding near the engine," wrote National Geographic journalist Luis Marden, "that seats in the rear of the train sold for five times the normal price." By April 1918, the Turks closed down the train from southern Jordan to Medina.

Lawrence did not watch from the distance, he was with his men on the front lines, avoiding bullets and sword blades. He sustained dozens of bullet and shrapnel wounds. On mining the rails in 1917 at Abu and Naam stations: "We lay like lizards...upon the hill-top, and saw the garrison parade. Three hundred and ninety-nine infantry, little toy men, ran about..." On another raid in the area he helped his men under fire make it to the rail. "We made our camels kneel down beside it, and...performed a sunset prayer quietly...from a distance we passed muster, and the Turks stopped shooting in bewilderment. This was the first and last time I ever prayed in Arabia as a Muslim."

Lawrence Captured and Raped

Seven Pillars of Wisdom in Wadi Rum, Jordan

Lawrence was frequently sick, hungry and sleepless. He embraced the hardship: seemingly begging for more rather than complaining about it. In May and June 1917, Lawrence and his forces disappeared into the desolate deserts around Wadi as Sirhan in what is now eastern Jordan. During that time he went into the desert alone to rescue a man named Gasim.

Lawrence was later captured by the Turks and severely beaten and raped. He managed to escape but was permanently shattered by the experience.”the code of my integrity has ben irrevocably lost,” he wrote. He wrote he was “homosexually brutalized before he was able to escape.”

MacIntyre wrote in the New York Times: “In November 1917, during an ill-advised attempt to reconnoiter an enemy camp in disguise, he was captured (though apparently not identified), savagely beaten and sexually abused by the local bey and his Turkish soldiers before escaping. The experience was shattering, but his own response to it shocked him still more. Having done so much to repress any trace of his own sexuality, he conceded to feeling, during his ordeal, “a delicious warmth, probably sexual, swelling through me.” ...Lawrence felt he had failed, “by giving in to pain and fear, by submitting himself to rape as an escape from the pain, and by discovering that despite himself he felt a forbidden sexual excitement.” This humiliation, and the twin shame of failing to secure the promised Arab state for his friends and allies after the war, haunted Lawrence for the rest of his life.” [Source: Ben MacIntyre, New York Times, December 24, 2010]

Lawrence and the Success of the Arab Revolt

Against tremendous odds, the revolt succeeded. On July 16, Lawrence and his raiders captured the Red Sea port of Aqaba in present-day Jordan after catching the Turkish garrison by surprise. The victory knocked out the last Ottoman stronghold on the Red Sea and provided a base for the Arabs to attack Damascus. In his book he wrote he rode a camel across the Sinai in 49 hours to deliver the news. Many scholars believe he made this up.

Arab Revolt

After this Lawrence was able to convince his British superiors that he was “the indispensable conduit through which arms and money must flow to the Arabs.” He also convinced the Arabs that he was committed to fighting for their independence not the strategic interest of the British. Even so he bribed Arab leaders (occasionally by mistake: once he sent £25,000 in gold to the wrong prince).

In late 1917 and 1918, while Lawrence’s forces continue to disrupt the Hejaz railway, Feisal’s army advanced northward. In September 1918, a Turkish column was slaughtered at Tafas, south of Damascus. Afterwards Turkish and German prisoners were massacred. The degree to which Lawrence was personally involved on this incident is of considerable debate.

On October 3, 1918, Feisal’s army entered Damascus after routing the Turks. But this was ultimately a hollow victory. The British denied them their kingdom. Lawrence wrote: “Had I been an honest advisor of the Arabs I would have advised them to go home” before having taken part on the revolt. Some of those close to Lawrence were rewarded. Lawrence was a friend of Churchill. He was instrumental in getting his friend Faisal installed as King of Iraq and his brother Abdullah as the king of Jordan.

Lawrence of Arabia’s Later Life

After returning to England, Lawrence wrote “Seven Pillars of Wisdom” (1935) about the Arab Revolt and his involvement in it. He initially wrote the book with notes that he had collected but after losing the manuscript while traveling on a train in England he rewrote the whole thing from memory. The book records heroic deeds and inspiring victories against the Turk but ends with a sense that promises were broken and hopes were compromised.

Lawrence's grave in the separate churchyard of St Nicholas Church, Moreton, Dorset, England

Lawrence became an international celebrity and added to his fame when he turned down medals of honor from the British king over the scandalous way the British had treated the Arabs. When he was at the peak of his fame he disappeared and joined the British Tank Corps under an alias. He served for several years, and lived in a barrack while he wrote acclaimed books and corresponded with Churchill, George Bernard Shaw and others.

Ben MacIntyre wrote in the New York Times: “During the moment of his greatest visibility, Lawrence chose obscurity... He tried to disguise himself, first as an R.A.F. airman, “John Hume Ross,” later as “T. E. Shaw” of the Royal Tank Corps, but his fame and his name followed him until the end. He was killed, at 46, when his huge Brough motorcycle skidded on a country road in Dorset. [Source: Ben MacIntyre, New York Times, December 24, 2010]

Lawrence retired from the military at the age of 46 and moved to a cottage in Dorset. A few months after he settled in, on May 13, 1935, he crested a hill on his motorcycle and saw two boys on bicycles. He swerved to miss them and crashed, and badly fractured his skull and died six days later. He left £100 pounds to the two executioners of his will. Lawrence is buried in a simple grave in an unkept graveyard in Dorset, England.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, BBC, Al Jazeera, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018