Home | Category: Colonialism and Slavery / Colonial Period in the Middle East

BATTLE OF THE NILE

Battle of the Nile

Within days after Napoleon defeated the Egyptians, the French fleet was destroyed by the British under Lord Nelson, ending French plans of further conquest. A British-Turkish alliance reclaimed the country with the successful blocked of the French army and the defeat of the French navy at Abu-Kir, near Alexandria. The British left in 1802.

Napoleon easily defeated the Mamluks but failed to watch his rear. On August 1, 1798, the British fleet under Lord Nelson annihilated the French ships as they lay at anchor at Abu Qir, thus isolating Napoleon's forces in Egypt. The entire French fleet was destroyed with the exception of four ships. On September 11, Sultan Selim III declared war on France.

The Battle of the Nile was one of the most important naval battles ever. It was more significant than Trafalgar which was like Normandy, while the Battle of the Nile was like Stalingrad. It ended Napoleon's ambition for Egypt and India and ended his plan to cut off Britain' source of wealth. If the British had lost they would have lost their toehold in the Mediterranean and the Middle East and made India vulnerable to attack and France might have been able to conquer the Ottoman Empire.

Islamic History: Islamic History Resources uga.edu/islam/history ; Internet Islamic History Sourcebook fordham.edu/halsall/islam/islamsbook ; Islamic History friesian.com/islam ; Islamic Civilization cyberistan.org ; Muslim Heritage muslimheritage.com ; Brief history of Islam barkati.net ; Chronological history of Islam barkati.net

See Separate Article FRENCH MOVE INTO NORTH AFRICA AND LOSE EGYPT factsanddetails.com

Modernization in the Middle East

Modernizing in the Middle East and North Africa meant trying to acquire Western military technology, railroads and luxuries but not reforming society with democracy or human rights. Cities, homes and customs became more Westernized. Opera houses were constructed. Women started traveling around in horse-drawn carriages. Homes were built with windows facing the street instead of courtyards. Printing in Arabic had hardly existed before the 19th century, but did afterwards thanks to the Europeans. European-style schools began replacing madrasahs (religious schools). European methods of administration were introduced.

During the nineteenth century, the socioeconomic and political foundations of the modern Egyptian state were laid. The transformation of Egypt began with the integration of the economy into the world capitalist system with the result that by the end of the century Egypt had become an exporter of raw materials to Europe and an importer of European manufactured goods. The transformation of Egypt led to the emergence of a ruling elite composed of large landowners of Turco-Circassian origin and the creation of a class of medium-sized landowners of Egyptian origin who played an increasingly important role in the political and economic life of the country. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990 *]

In the countryside, peasants were dispossessed because of debt, and many landless peasants migrated to the cities where they joined the swelling ranks of the under and unemployed. In the cities, a professional middle class emerged composed of civil servants, lawyers, teachers, and technicians. Finally, Western ideas and cultural forms were introduced into the country. *

Colonialism in the Middle East and North Africa

As time went on Europe got stronger and richer and began eyeing counties in the Muslim world as sources of raw materials and markets for it goods as outright colonies. The countries that were colonized found their local economies destroyed as their populations were mobilized to produce and consume goods for their mother country — European countries, mostly Britain and France — rather for themselves. In many ways, the mother country reduced the colonized country to second class status and the people in the mother country began to think of themselves as superior and feel it was their duty to civilize the people in the colony. French and English began replacing Arabic The Arab elite was fascinated by the West. Future kings and generals attended Victoria College in Alexandria where they were trained to be English gentlemen. Many also studied at Oxford, Cambridge and Sandhurst.

cotton in Jerusalem in 1880

Throughout the 19th century the European nations put pressure on the emerging states in North Africa by controlling trade, defining the terms of the trade and forcing the Arab states to become indebted to them so they could demand concessions. European migrants arrived. Many worked for their home government or had business interests. They lived in special enclaves. British, Ottoman and Egyptian actions against slavery and the slave trade finally brought slavery to an end in what was the Ottoman Empire in 1914.

Cotton in Egypt

By 1820, French engineer Louis Jumel discovered a long-staple cotton in his garden in Egypt that proved to be ideal of top-of -the line textiles. From that time forward large and larger amounts of land was turned over to the production of cotton.

The Egyptian cotton industry took off when the supply of cotton from the United States was cut off during the American Civil War in the 1860s.

Textile factories in Lancashire, England were dependent on Egyptian cotton. The cotton was sent to Britain and in some cases was made into finished products that were sent back and sold in the Middle East — a classic example of dependency theory (the notion of resources flowing from a "periphery" of poor and underdeveloped states to a "core" of wealthy states, enriching the latter at the expense of the former).

The cotton boon also lead to population growth as parents wanted to have more children to work the fields and earn money for the family. The profitability of cotton made it more advantageous grow cotton than food

Suez Canal

In 1856 Said Pasha, Muhammad Ali's son, granted a French company the right to build the Suez Canal. The modern Suez Canal (75 miles west of Cairo) is the world's longest large ship canal. Extending from Port Said lighthouse to Suez Roads, it is 162 kilometers (100.8 miles) long and ranges from 302 meters (984 feet) to 365 meters (1,198 feet) wide. It is also the busiest canal in terms of tonnage: 417,852,000 gross tons were registered in 1995.

Connecting the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea, it enables ships traveling between Asia and Europe to avoid going thousands of extra miles around Africa, through the dangerous waters off the Cape of Good Hope. The distance between London and Bombay through the canal is 11,782 kilometers (7,321 miles), compared to 19,878 kilometers (12,352 miles) without it.

Unlike the Panama Canal, the Suez Canal can accommodate all but the largest supertankers. Extending from Port Said on the Mediterranean Sea to Suez on the Gulf of Suez (a branch of the Red Sea), the canal averages 320 yards wide and to 23.5 meters (77 feet) deep. It includes two lakes—the Great Bitter Lake and Little Bitter Lake—and is paralleled by a narrow canal called the Sweet Water Canal. This canal carries water from the Nile to irrigate land on the Sinai peninsula.

Traversing the Suez Canal takes a ship about 14 hours. Ships passes through canal one direction at a time in convoys so that ships going in opposite directions never pass one another within the waterway. The ships wait near Port Said and Suez until it there time to go. The convoys going in opposite directions pass each other in the lakes. To actually navigate the canal all ship captains are required to take on a pilot who is paid a salary and a per boat bonus.

See Separate Article FRENCH MOVE INTO NORTH AFRICA AND LOSE EGYPT factsanddetails.com

Suez Canal

British Take Over the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal opened in 1869. Khedive Ismail (the Turkish viceroy and effective leader of Egypt) hired Verdi to write the opera “Aida” and invited over 1000 Europeans, including Empress Eugénie of France (wife of Napoleon III), the Emperor of Austria, the crown prince of Prussia and the writers Émile Zola and Henrik Ibsen for the opening ceremony. According to a 99-year concession established by the French the canal would be the property of the Suez Company until 1968 when it would be turned over to Egypt. The Suez Company was a private Egyptian corporation with offices in Paris.

The king hosted the first ever joint Muslim-Christian religious service in history, organized a cruise through the canal for the dignitaries, and built a new palace along the canal for the opening party for 5,000 guests who stayed the night. Around 35,000 other guests partied in tents and feasted on roasted sheep outside the palace.

The four-day celebration was so big many guest spent some of their time tracking down lost luggage and looking for their companions. One official commented, "We must be eating up the pyramids stone by stone." The khedive paid for all expenses for his important guests and commissioned a road from the pyramids to the canal so that guests could travel to the celebration. These and other lavish expenditures by the khedive helped bankrupt the country.

Six years after the canal opened it was taken over by the British government, which obtained a £4 million loan from Rothschild to purchase of 176,602 shares of Suez stock (43 percent of all the stock) from the Khedive of Egypt, whose high living and grandiose projects left him desperately in need of cash to pay off his creditors.

Rothschild tipped off British Prime Minister Disraeli about the Khedive's debts. The money was delivered secretly so not to arouse the suspicions of the French. Disraeli presented the canal to the queen as a gift and the British press labeled Rothschild as the Jewish member of the House of Lords who really ran the country.

The French continued to have a stake a in the canal but the shares it received from the king gave the British control. The Anglo-French combine—the Société Universelle du canal Maratime de Suez—continued to own the canal until was nationalized by the Egyptian government in 1956.

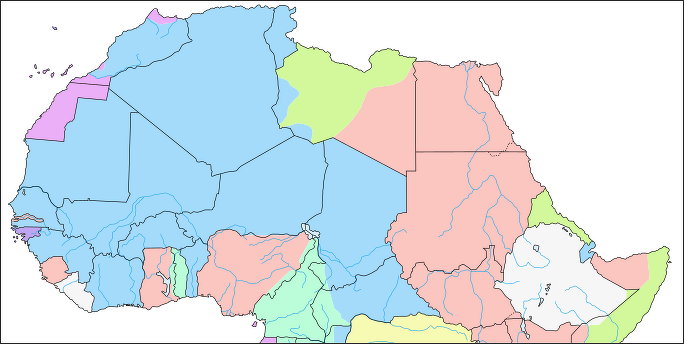

Map of colonial Africa in 1913 with British possessions in pink, French in blue and Italian in green

Early British Colonialism in Egypt

Britain occupied Egypt in 1882 and retained control there until the revolution of 1952. In the waning years of the Ottoman Empire, the British took control of the nation through political maneuvering and underhanded financial dealings that continued after they took control of Suez Canal.

After selling his Suez shares to Britain, Ismail, the leader of of Egypt and Sudan from 1863 to 1879, had severe financial troubles. In 1876, he permitted British and French officials to oversee Egypt's fiances. In 1882, Egyptians revolted. The French left and Britain brought in an occupying force, which made Egypt virtually a British colony while it was still part of the Ottoman Empire.

The British helped Egypt modernize. Dams were built in Aswan, the railroad was improved. Industry and trade were encouraged and Egypt became financially solvent. The British divided the river people from the Bedouins. As late as 1965 people living around the Nile needed a permit to visit Bedouin lands.

In the late 19th century many British with tuberculosis traveled to Egypt under the assumption that the warm weather would nurse them back to health. Many of the Brits that lived in Egypt long yerm confined themselves to the British enclave in Cairo, which one of Kitchener aides said possessed "all the narrowness and provincialism of an English garrison town." The social scene revolved around balls given at the top hotels and the Turf Club and the Sporting Club on the island of El Gezira.

British Intervention to Occupation, 1876-82

Seriously concerned with the country's financial situation, Ismail asked for British help in fiscal reform. Britain responded by sending Steven Cave, a member of Parliament, to investigate. Cave judged Egypt to be solvent on the basis of its resources and said that all the country needed to get back on its feet was time and the proper servicing of the debts. Cave recommended the establishment of a control commission over Egypt's finances to approve all future loans. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990 *]

Battle of El-Tel El-Kebir in 1882

European creditors, however, would not allow Egypt time. When Ismail suspended payment of interest on the loans in 1875, his creditors in Britain and France appointed two men to represent their interests and negotiate new arrangements with the khedive. The Goschen-Joubert Mission achieved three things: the consolidation of the debt; the appointment of two European controllers, one British and one French; and the establishment of the Caisse de la Dette Publique, a special department with representatives from the various European creditor states to ensure the service of the debt. Revenue from the most productive provinces went straight to the department, and by 1877 more than 60 percent of all Egyptian revenue went to service the national debt.*

Although Egypt serviced the debt faithfully, European intervention increased. At the insistence of the French, a commission of inquiry was appointed in 1878 to examine all sources of revenue and expenditure. The commission had the right to ask any Egyptian official or government deputy to testify before it and to subpoena all records. Such powers implied the dilution of Egyptian sovereignty by Europeans.*

The commission report indicted the khedival government and suggested limiting Ismail's power as a first step in solving the country's financial problems. The khedive accepted the commission's conditions, including a cabinet containing Europeans and the principle of ministerial responsibility. He appointed Nubar Pasha as prime minister and asked him to form a government containing two Europeans. Many Europeans were appointed at high salaries in various government departments; thirty British officers were appointed to the Land Survey Department alone. Ismail was also forced to delegate governmental responsibility to his cabinet, which was made independent of the khedive and responsible for the administration of the country.*

Opposition to British Intervention in Egypt, 1876-82

Opposition to European intervention in Egypt's internal affairs emerged from the Assembly of Delegates, which Ismail had created in 1866, and from the Egyptian army officers. The assembly, composed mainly of Egyptian notables, had no legislative power. It was Ismail's attempt to associate the Egyptian notables with his financial policies, and thus, to demonstrate support for his taxes and foreign loans. The presence of Egyptian officers in the army resulted from the 1854 decree of Said, who ordered the sons of village notables to join the army. Said allowed them to be trained as officers and to rise to the rank of colonel, but the top posts in the army continued to be held by members of the Turco-Circassian elite. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990 *]

anti-British protests in Cairo

The Assembly of Delegates, meeting between January and July 1879, demanded more control over financial matters and accountability of the European ministers to the assembly. At the same time, a group of Egyptian army officers who opposed the mixed cabinet protested the placing of 2,500 officers on half- pay. A group of army officers marched on the Ministry of Finance and occupied the building. Only the personal intervention of the khedive, who was suspected of instigating the incident, saved the situation. At this point, Ismail realized that he could use both the assembly and the army officers to rid himself of foreign control.*

In April 1879, Ismail's opportunity came. Under foreign pressure, Ismail ordered the assembly to dissolve. Its members refused, saying they represented the nation and would not relinquish their mandate at the order of the khedive, influenced and pressured as he was by foreign powers. On March 29, they presented a manifesto to the khedive protesting the Council of Ministers' attempts to usurp their power and authority. They also stated their determination to reject the European ministers' demand that Egypt declare itself bankrupt.*

The leader of the delegates was the constitutionally minded Muhammad Sharif Pasha, who was among the members of a secret society called the National Society (later the Hulwan Society). The society had drawn up a plan for national reform (Laiha Wataniyah) that proposed constitutional and financial reforms to increase the power of the assembly and resolve Egypt's financial problems without foreign advisers or control.*

In a shrewd political move, Ismail summoned the European consuls and confronted them with the discontent of the delegates, the disaffection in the army, and the general public uneasiness. He informed them that he had decided to act in accordance with the resolutions of the assembly. Therefore, he rejected the proposal to declare Egypt bankrupt and stated his intent to meet all obligations to Egypt's creditors. He also invited Sharif Pasha to form a government. Sharif Pasha and his Egyptian cabinet dismissed the European ministers.*

Although these actions made Ismail popular at home, they threatened continued European control over Egypt's finances. The European powers, particularly Britain and France, decided Ismail had to go. Since he refused to abdicate, the European powers put pressure on the Ottoman sultan to dismiss him in favor of his son Tawfiq. On June 26, 1879, he received a telegram from the grand vizier addressed to "the ex-khedive Ismail." Ismail left Egypt for exile in Naples and subsequently in Istanbul, where he died in 1895.*

Egyptian and British soldiers in 1919

Tawfiq proved to be a more pliable instrument in the hands of the European powers. The dual control of Egypt's finances was reinstituted. An international commission of liquidation was appointed with British, French, Austrian, and Italian members. In July 1880, the Law of Liquidation was promulgated, limiting Egypt to 50 percent of its total revenues. The rest went to the Caisse de la Dette Publique to service the debt. The Assembly of Delegates remained dissolved.*

The direct interference of Europeans in Egypt's affairs and the deposition of Khedive Ismail forged a nationalist movement composed of Egyptian landowners and merchants, especially former members of the assembly, Egyptian army officers, and the intelligentsia, including the ulama and Muslim reformers. A secret society of Egyptian army officers had also come into existence in 1876, comparable to the secret society of Egyptian notables. The army society included Colonel Ahmad Urabi, who would become the leader of the nationalist movement, and colonels Ali Fahmi and Abd al Al Hilmi. In 1881 a link, if not a merger, was formed between the Urabists and the National Society. This expanded group took the name Al Hizb al Watani al Ahli, the National Popular Party.*

European Military Activity in Late 19th Century Egypt

Beginning in 1881, the army officers demonstrated their strength and their ability to intimidate the khedive. They began with a mutiny provoked by the anti-Urabist minister of war. Not only were they able to force the appointment of a more sympathetic minister but by January 1882, Urabi joined the government as undersecretary for war.*

These developments alarmed the European powers, particularly Britain and France. Britain was especially concerned about protecting the Suez Canal and the British lifeline to India. In January 1882, Britain and France sent a joint note declaring their support for the khedive. The note had the opposite effect from that intended, producing an upsurge in anti-European feeling, a shift in leadership of the nationalist movement from the moderates in the assembly to the military, and the formation of a new government with Urabi as minister of war. At this point, the goal of Urabi and his followers became not only the removal of all European influence from Egypt but also the overthrow of the khedive.*

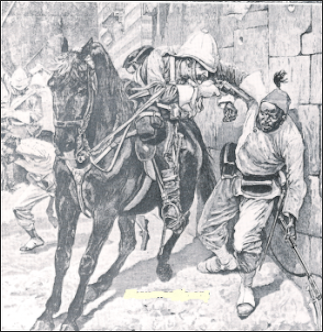

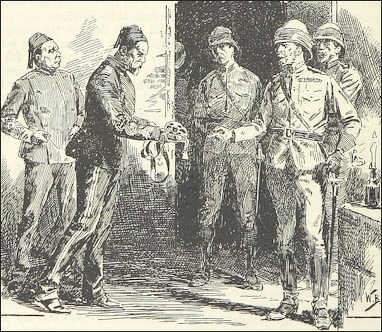

Surrender of Ahmed Urabi

In another attempt to break Urabi's power, the British and French agreed on a joint show of naval strength. They also issued a series of demands including the resignation of the government, the temporary exile of Urabi, and the internal exile of his two closest associates, Ali Fahmi and Abd al Al Hilmi. As a result, violent anti-European riots broke out in Alexandria with considerable loss of life on both sides.*

During the summer, an international conference of the European powers met in Istanbul, but no agreement was reached. The Ottoman sultan Abdul Hamid boycotted the conference and refused to send troops to Egypt. Eventually, Britain decided to act alone. The French withdrew their naval squadron from Alexandria, and in July 1882, the British fleet began bombarding Alexandria.*

Following the burning of Alexandria and its occupation by British marines, the British installed the khedive in the Ras at Tin Palace. The khedive obligingly declared Urabi a rebel and deprived him of his political rights. Urabi in turn obtained a religious ruling, a fatwa, signed by three Al Azhar shaykhs, deposing Tawfiq as a traitor who brought about the foreign occupation of his country and betrayed his religion. Urabi also ordered general conscription and declared war on Britain. Thus, as the British army was about to land in August, Egypt had two leaders: the khedive, whose authority was confined to British-controlled Alexandria, and Urabi, who was in full control of Cairo and the provinces.*

In August Sir Garnet Wolsley and an army of 20,000 invaded the Suez Canal Zone. Wolsley was authorized to crush the Urabi forces and clear the country of rebels. The decisive battle was fought at Tall al Kabir on September 13, 1882. The Urabi forces were routed and the capital captured. The nominal authority of the khedive was restored, and the British occupation of Egypt, which was to last for seventy-two years, had begun.*

Urabi was captured, and he and his associates were put on trial. An Egyptian court sentenced Urabi to death, but through British intervention the sentence was commuted to banishment to Ceylon. Britain's military intervention in 1882 and its extended, if attenuated, occupation of the country left a legacy of bitterness among the Egyptians that would not be expunged until 1956 when British troops were finally removed from the country. *

Britain Takes Over Egypt in 1882

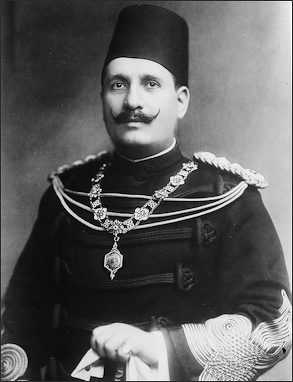

Khedive of Egypt

With the khedive unable to meet the financial obligations the British began taking steps to limit his power. The khedive responded by creating a Chamber of Deputies led by a army officer to assert Egyptian independence. Britain with the help of France tried to thwart this move by applying diplomatic pressure. When that didn’t work Britain acted alone militarily, and invaded Egypt and seized control of the government in 1882. The British claimed that the Egyptians were revolted against legitimate British aithority and went in to restore order. Few historians see it that way. Most see it as a bold seizure of power based on a flimsy excuse.

With the occupation of 1882, Egypt became a part of the British Empire but never officially a colony. The khedival government provided the facade of autonomy, but behind it lay the real power in the country, specifically, the British agent and consul general, backed by British troops.*

At the outset of the occupation, the British government declared its intention to withdraw its troops as soon as possible. This could not be done, however, until the authority of the khedive was restored. Eventually, the British realized that these two aims were incompatible because the military intervention, which Khedive Tawfiq supported and which prevented his overthrow, had undermined the authority of the ruler. Without the British presence, the khedival government would probably have collapsed.*

In addition, the British government realized that the most effective way to protect its interests was from its position in Egypt. This represented a change in the policy that had existed since the time of Muhammad Ali, when the British were committed to preserving the Ottoman Empire. The change in British policy occurred for several reasons. Sultan Abdul Hamid had refused Britain's request to intervene in Egypt against Urabi and to preserve the khedival government. Also, Britain's influence in Istanbul was declining while that of Germany was rising. Finally, Britain's unilateral invasion of Egypt gave Britain the opportunity to supplant French influence in the country. Moreover, Britain was determined to preserve its control over the Suez Canal and to safeguard the vital route to India.*

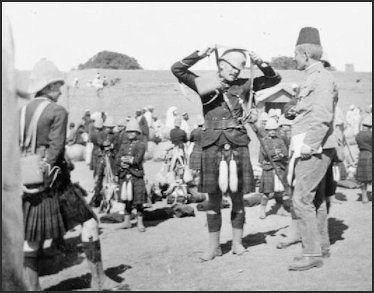

members of General Kitchener's 1898 Anglo-Egyptian Nile campaign

Between 1883 and the outbreak of World War I in 1914, there were three British agents and consuls general in Egypt: Lord Cromer (1883-1907), Sir John Eldon Gorst (1907-11), and Lord Herbert Kitchener (1911-14). Cromer was an autocrat whose control over Egypt was more absolute than that of any Mamluk or khedive. Cromer believed his first task was to achieve financial solvency for Egypt. He serviced the debt, balanced the budget, and spent what money remained after debt payments on agriculture, irrigation, and railroads. He neglected industry and education, a policy that became a political issue in the country. He brought in British officials to staff the bureaucracy. This policy, too, was controversial because it prevented Egyptian civil servants from rising to the top of their fields.*

Gorst, who was less autocratic than Cromer, had to face a growing Egyptian nationalism that demanded British evacuation from the country. Gorst's attempt to create a "moderate" nationalism ultimately failed because the nationalists refused to make any compromises over independence and because Britain considered any concession to the nationalists a sign of weakness.

British Egypt and World War I

In the year 1900, Egypt was part of the Ottoman Empire in name but was governed behind the scene by British "advisors" led by the British Agent and Consular General. The Egyptian army was commanded by an English general. Turkish police, soldiers and officials were conspicuous by their absence. Few people could even speak Turkish.

British forces based in Egypt put down a religious revolt in the Sudan. In 1899, the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan was established under British rule.

Horatio Herbert Kitchener was appointed the British Agent and Consular General in 1911. When Kitchener arrived in Egypt, he was already famous as the man who had avenged the death of General Charles Gordon in Khartoum in 1885 during the Mahdist uprising. In 1913 Kitchener introduced a new constitution that gave the country some representative institutions locally and nationally. When the British occupation began, the Assembly of Delegates had ceased to exist. It was superseded by an assembly and legislative council that were consultative bodies whose advice was not binding on the government. The Organic Law of 1913 provided for a legislative assembly with an increased number of elected members and expanded powers.*

members of General Kitchener's 1898 Anglo-Egyptian Nile campaign

On October 29, 1914, the Ottoman Empire entered World War I on the side of the Central Powers. Martial law was declared in Egypt on November 2. On November 3, the British government unilaterally declared Egypt a protectorate, severing the country from the Ottoman Empire. Britain deposed Khedive Abbas, who had succeeded Khedive Tawfiq upon the latter's death in 1892, because Abbas, who was in Istanbul when the war broke out, was suspected of pro-German sympathies. Kitchener was recalled to London to serve as minister of war.*

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994). “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, BBC, Al Jazeera, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018