Home | Category: Colonialism and Slavery / Colonial Period in the Middle East

DECLINE OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE

Ottoman Harem

According to the BBC: “The power of the empire was waning by 1683 when the second and last attempt was made to conquer Vienna. It failed. Without the conquest of Europe and the acquisition of significant new wealth the Empire lost momentum and went into a slow decline. [Source: BBC, September 4, 2009 |::|]

The Ottoman Empire began to show more serious signs of decline in the eighteenth century. By the nineteenth century European powers had begun to take advantage of Ottoman weakness through both military and political penetration, including Napoleon's invasion of Egypt, subsequent British intervention, and French occupation of Lebanon. Economic development of Syria through the use of European capital — for example, railroads built largely with French money — brought further incursions. [Source: Thomas Collelo, ed. Syria: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1987 *]

“Several other factors contributed to the Empire's decline: 1) The European powers wanted to expand; 2) Economic problems; 3) Competition from trade from the Americas; 4) Competition from cheap products from India and the Far East; 5) Development of other trade routes; 6) Rising unemployment within the Empire; 7) Ottoman Empire became less centralised, and central control weakened; 8) Sultans being less severe in maintaining rigorous standards of integrity in the adminstration of the Empire; 9) Sultans becoming less sensitive to public opinion; 10) The low quality Sultans of the 17th and 18th centuries; 11) The ending of the execution of Sultan's sons and brothers, imprisoning them instead; 12) This apparently humane process led to men becoming Sultan after spending years in prison - not the best training for absolute power |::|

“Soon the very word Turk became synonymous with treachery and cruelty. This led Turks like Kemal Ataturk, who was born late in the nineteenth century, to be repelled by the Ottoman Turkish political system and the culture it had evolved. Seeing little but decay and corruption, he led the Turks to create a new modern identity. |::|

“The empire officially ended on the 1st November 1922, when the Ottoman sultanate was abolished and Turkey was declared a republic. The Ottoman caliphate continued as an institution, with greatly reduced authority, until it too was abolished on the 3rd March 1924. |::|

Islamic History: Islamic History Resources uga.edu/islam/history ; Internet Islamic History Sourcebook fordham.edu/halsall/islam/islamsbook ; Islamic History friesian.com/islam ; Islamic Civilization cyberistan.org ; Muslim Heritage muslimheritage.com ; Brief history of Islam barkati.net ; Chronological history of Islam barkati.net

See Separate Article BRITISH MOVE INTO THE MIDDLE EAST factsanddetails.com

Survey of the Turkish Empire, 1799

Sir William Eton wrote in “A Survey of the Turkish Empire, 1799: “It is undeniable that the power of the Turks was once formidable to their neighbors not by their numbers only, but by their military and civil institutions, far surpassing those of their opponents. And they all trembled at the name of the Turks, who with a confidence procured by their constant successes, held the Christians in no less in contempt as warriors than they did on account of their religion. Proud and vainglorious, conquest was to them a passion, a gratification, and even a means of salvation, a sure way of immediately attaining a delicious paradise. Hence their zeal for the extension of their empire; hence their profound respect for the military profession, and their glory even in being obedient and submissive to discipline. [Source: Sir William Eton, A Survey of the Turkish Empire (London, 1799), pp. 61-62, 68-75, 98-101, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

Was the Middle East sleepy, or just peaceful under the Ottomans

“Besides that the Turks refuse all reform, they are seditious and mutinous; their armies are encumbered with immense baggage, and their camp has all the conveniences of a town, with shops etc. for such was their ancient custom when they wandered with their hordes. When their sudden fury is abated, which is at the least obstinate resistance, they are seized with a panic, and have no rallying as formerly. The cavalry is as much afraid of their own infantry as of the enemy; for in a defeat they fire at them to get their horses to escape more quickly. In short, it is a mob assembled rather than an army levied. None of those numerous details of a well-organized body, necessary to give quickness, strength, and regularity to its actions, to avoid confusion, to repair damages, to apply to every part to some use; no systematic attack, defense, or retreat; no accident foreseen, nor provided for...

“The artillery they have, and which is chiefly brass, comprehends many find pieces of cannon; but notwithstanding the reiterated instruction of so many French engineers, they are ignorant of its management. Their musket-barrels are much esteemed but they are too heavy; nor do they possess any quality superior to common iron barrels which have been much hammered, and are very soft Swedish iron. The art of tempering their sabers is now lost, and all the blades of great value are ancient. The naval force of the Turks is by no means considerable. Their grand fleet consisted of not more than seventeen or eighteen sail of the line in the last war [Russo-Turkish war of 1787-92], and those not in very good condition; at present their number is lessened.

“The present reigning Sultan, Selim III, has made an attempt to introduce the European discipline into the Turkish army, and to abolish the body of the Janissaries. [He has] caused a corps to be recruited, set apart a branch of the revenue for their maintenance, and finally declared his intention of abolishing the institution of Janissaries. This step, as might be expected, produced a mutiny, which was only appeased by the sultan's consenting to continue their pay during their lifetimes; but he at the same time ordered that no recruits should be received into their corps. The new soldiers in the corps are taught their exercise with the musket and bayonet, and a few maneuvers. When they are held to be sufficiently disciplined, they are sent to garrison the fortresses on the frontiers. Their officers are all Turks and are chosen out of those who perform their exercise the best.”

Napoleon and the French Invasion of Egypt in 1798

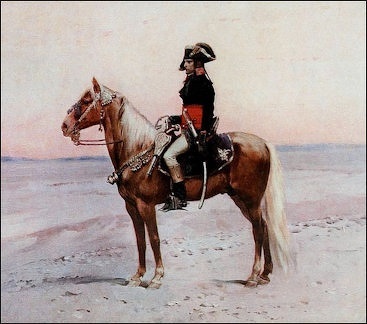

Napoleon in Egypt

Napoleon landed in Egypt in May, 1798 with 55,000 troops and an armada of 400 vessels. He arrived, purportedly to support the Ottomans, who were having difficulty maintaining control, and then proceeded to defeat a Turkish-Mamluk army in the Battle of the Pyramids. Napoleon's aim was to gain control of the trade routes to India and "civilize" Egypt. He had hoped to establish a base in the Suez that cut British sea routes to India and ultimately attack British India from the north with Russian help.

To backtrack a little first, after the death of Muhammad Bey in Egypt, there was a decade-long struggle for dominance among the beys. Eventually Ibrahim Bey and Murad Bey succeeded in asserting their authority and shared power in Egypt. Their dominance in the country survived an unsuccessful attempt by the Ottomans to reestablish the empire's control (1786-91). The two continued in power until the French invasion in 1798. In addition to the upheavals caused by the Ottoman-Mamluk clashes, waves of famine and plague hit Egypt between 1784 and 1792. Thus, Cairo was a devastated city and Egypt an impoverished country when the French arrived in 1798. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990 *]

On July 1, 1798, a French invasion force under the command of Napoleon disembarked near Alexandria. The invasion force, which had sailed from Toulon on May 19, was accompanied by a commission of scholars and scientists whose function was to investigate every aspect of life in ancient and contemporary Egypt.*

France wanted control of Egypt for two major reasons — its commercial and agricultural potential and its strategic importance to the Anglo-French rivalry. During the eighteenth century, the principal share of European trade with Egypt was handled by French merchants. The French also looked to Egypt as a source of grain and raw materials. In strategic terms, French control of Egypt could be used to threaten British commercial interests in the region and to block Britain's overland route to India.*

The French forces took Alexandria without difficulty, defeated the Mamluk army at Shubra Khit and Imbabah, and entered Cairo on July 25. Murad Bey fled to Upper Egypt while Ibrahim Bey and the Ottoman viceroy went to Syria. Mamluk rule in Egypt collapsed.*

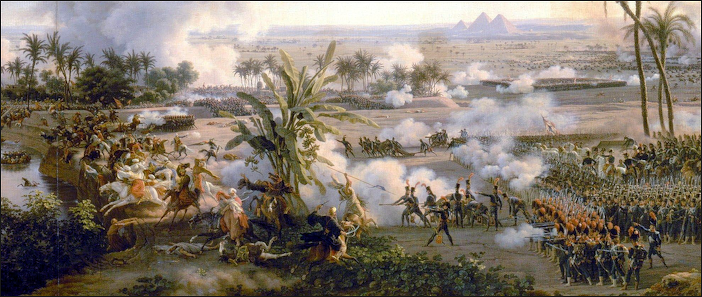

Battle of the Pyramids

The Mamluks — the great slave horse-mounted warriors that brought the Mongol advance to a halt — were a force to be reckoned with into the early 1800s. When word arrived that the French had arrived in Alexandria, the Mamluk leader reportedly boasted: “relying on their strength and their claim that if all the Franks came they would not be able to stand against them, and they would crush them beneath their horse’s hooves.” But in end Mamluk horsemen, with their scimitars flashing in the Egyptian sun, were almost comically mowed down by French artillery and gunfire during a battle in front of the Pyramids.

Battle of the Pyramids

The most important battle of Napoleon’s invasion, the Battle of the Pyramids, took place on July 21, 1798 on the Nile at Embabab, within sight of the pyramids. Napoleon told his men "40 centuries of history look down on you." French artillery and "impregnable infantry squares” crushed the brave but antiquated force of 78,000 Mameluks that fled in panic. Thousands of Mamluks died while only 30 Frenchmen died.

Within a short time, the French were able to claim all Egypt. Muslims felt humiliation as Europeans had struck deep into their heartland and the only people that could get rid of them were other Europeans—the British. Napoleon’s Egyptian adventure ultimately ended in failure His expedition into Egypt was brought to an end when admiral Nelson obliterated the French fleet and imposed a naval blockade that prevented the French from receiving supplies.

Battle of the Nile

Within days after Napoleon defeated the Egyptians, the French fleet was destroyed by the British under Lord Nelson, ending French plans of further conquest. A British-Turkish alliance reclaimed the country with the successful blocked of the French army and the defeat of the French navy at Abu-Kir, near Alexandria. The British left in 1802.

Napoleon easily defeated the Mamluks but failed to watch his rear. On August 1, 1798, the British fleet under Lord Nelson annihilated the French ships as they lay at anchor at Abu Qir, thus isolating Napoleon's forces in Egypt. The entire French fleet was destroyed with the exception of four ships. On September 11, Sultan Selim III declared war on France.

The Battle of the Nile was one of the most important naval battles ever. It was more significant than Trafalgar which was like Normandy, while the Battle of the Nile was like Stalingrad. It ended Napoleon's ambition for Egypt and India and ended his plan to cut off Britain' source of wealth. If the British had lost they would have lost their toehold in the Mediterranean and the Middle East and made India vulnerable to attack and France might have been able to conquer the Ottoman Empire.

Napoleon battling the Mamluks in 1798

French Occupation of Egypt 1798-1801

The French occupied Egypt for three years. The booty he claimed in Egypt eventually formed the basis of he massive Egyptian collection in the Louvre. Among the prizes were the Rosetta stone. Napoleon brought scholars with him, giving rise to the study of Egyptology, and Egyptian fashion became all the rage in Paris. After it was conquered by Napoleon, Egypt became a close political ally of France and French culture was held in high esteem by the Egyptian upper classes.

Napoleon's position in Egypt was precarious. The French controlled only the Delta and Cairo; Upper Egypt was the preserve of the Mamluks and the bedouins. In addition, Britain and the Ottoman government joined forces in an attempt to defeat Napoleon and drive him out of Egypt. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990 *]

On October 21, 1798 the people of Cairo rioted against the French, whom they regarded as occupying strangers, not as liberators. The rebellion had a religious as well as a national character and centered around Al Azhar mosque. Its leaders were the ulama, religiously trained scholars, whom Napoleon had tried to woo to the French side. During this period, the populace began to regard the ulama not only as moral but also as political leaders.*

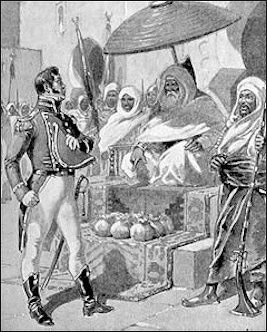

Napoleon Invades Syria and Retreats from the Middle East

To forestall an Ottoman invasion, Napoleon invaded Syria, but, unable to take Acre in Palestine, his forces retreated on May 20, 1799. On August 22, Napoleon, with a very small company, secretly left Egypt for France, leaving his troops behind and General Jean-Baptiste Kléber as his successor. Kléber found himself the unwilling commander in chief of a dispirited army with a bankrupt treasury. His main preoccupation was to secure the evacuation of his troops to France. When Britain rejected the evacuation plan, Kléber was forced to fight. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990 *]

After Kléber's assassination by a Syrian, his command was taken over by General Abdullah Jacques Menou, a French convert to Islam. The occupation was finally terminated by an Anglo-Ottoman invasion force. The French forces in Cairo surrendered on June 18, 1801, and Menou himself surrendered at Alexandria on September 3. By the end of September, the last French forces had left the country.*

Napoleon in Syria

Impact of Napoleon’s Adventure in Egypt

As historian Afaf Lutfi al-Sayyid Marsot has written, the three-year French occupation was too short to exert any lasting effects on Egypt, despite claims to the contrary. Its most important effect on Egypt internally was the rapid decline in the power of the Mamluks. The major impact of the French invasion was the effect it had on Europe. Napoleon's invasion revealed the Middle East as an area of immense strategic importance to the European powers, thus inaugurating the Anglo-French rivalry for influence in the region and bringing the British into the Mediterranean. The French invasion of Egypt also had an important effect on France because of the publication of Description de l'Egypte, which detailed the findings of the scholars and scientists who had accompanied Napoleon to Egypt. This publication became the foundation of modern research into the history, society, and economics of Egypt. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990 *]

The defeat was a jolt for the proud Egyptians, and would play a major part in opening up and modernization of Egypt in the 19th century and later the entire Arab world. At first the defeat was seen as the will of God, said one Egyptian historian. "Later we understood that the reason for our defeat was the difference between the medieval and modern world. We began to watch the French...their courts, their doctors, even their cabarets...The English would occupy us later, but the French stayed in our minds: the idea of the French Revolution, their manners, their language. To this day the old ladies of our elite class speak French."

Napoleon arguable triggered the drive towards modernization in the Arab-Muslim world. He brought with him scholars, a library with modern Europe literature, a scientific laboratory and a printing press with Arabic type. The Egyptian writer Rifah al-Tahtawi (1801-73) visited Paris and became intoxicated with the ideas of the European enlightenment. He was impresed by high literacy rates among ordinary people and the way society functioned so well. He did what he could to bring these ideas to Egypt.

France in Algeria

As a result of what the French considered an insult to the French consul in Algiers by the dey in 1827, France blockaded Algiers for three years. France then used the failure of the blockade as a reason for a military expedition against Algiers in 1830. By 1848 nearly all of northern Algeria was under French control, and the new government of the Second Republic declared the occupied lands an integral part of France. Three "civil territories"—Algiers, Oran, and Constantine—were organized as French “départements “(local administrative units) under a civilian government. “Colons “(colonists), or, more popularly, “pieds noirs “(literally, black feet) dominated the government and controlled the bulk of Algeria’s wealth. Throughout the colonial era, they continued to block or delay all attempts to implement even the most modest reforms. [Source: Library of Congress, May 2008]

Most of France's actions in Algeria, not least the invasion of Algiers, were propelled by contradictory impulses. In the period between Napoleon's downfall in 1815 and the revolution of 1830, the restored French monarchy was in crisis, and the dey was weak politically, economically, and militarily. The French monarch sought to reverse his domestic unpopularity. As a result of what the French considered an insult to the French consul in Algiers by the dey in 1827, France blockaded Algiers for three years. France used the failure of the blockade as a reason for a military expedition against Algiers in 1830. [Source: Helen Chapan Metz, ed. Algeria: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1994 *]

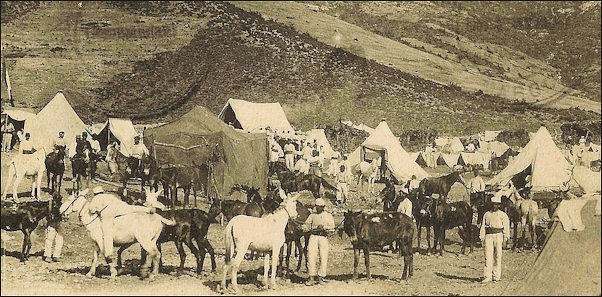

Invasion of Algiers

Using Napoleon's 1808 contingency plan for the invasion of Algeria, 34,000 French soldiers landed twenty-seven kilometers west of Algiers, at Sidi Ferruch, on June 12, 1830. To face the French, the dey sent 7,000 janissaries, 19,000 troops from the beys of Constantine and Oran, and about 17,000 Kabyles. The French established a strong beachhead and pushed toward Algiers, thanks in part to superior artillery and better organization. Algiers was captured after a three-week campaign, and Hussein Dey fled into exile. French troops raped, looted (taking 50 million francs from the treasury in the Casbah), desecrated mosques, and destroyed cemeteries. It was an inauspicious beginning to France's self-described "civilizing mission," whose character on the whole was cynical, arrogant, and cruel. [Source: Helen Chapan Metz, ed. Algeria: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1994 *]

Hardly had the news of the capture of Algiers reached Paris than Charles X was deposed, and his cousin Louis Philippe, the "citizen king," was named to preside over a constitutional monarchy. The new government, composed of liberal opponents of the Algiers expedition, was reluctant to pursue the conquest ordered by the old regime, but withdrawing from Algeria proved more difficult than conquering it. A parliamentary commission that examined the Algerian situation concluded that although French policy, behavior, and organization were failures, the occupation should continue for the sake of national prestige. In 1834 France annexed the occupied areas, which had an estimated Muslim population of about 3 million, as a colony. Colonial administration in the occupied areas--the so-called régime du sabre (government of the sword)--was placed under a governor general, a high-ranking army officer invested with civil and military jurisdiction, who was responsible to the minister of war.*

Modernization in the Middle East

Modernizing in the Middle East and North Africa meant trying to acquire Western military technology, railroads and luxuries but not reforming society with democracy or human rights. Cities, homes and customs became more Westernized. Opera houses were constructed. Women started traveling around in horse-drawn carriages. Homes were built with windows facing the street instead of courtyards. Printing in Arabic had hardly existed before the 19th century, but did afterwards thanks to the Europeans. European-style schools began replacing madrasahs (religious schools). European methods of administration were introduced.

During the nineteenth century, the socioeconomic and political foundations of the modern Egyptian state were laid. The transformation of Egypt began with the integration of the economy into the world capitalist system with the result that by the end of the century Egypt had become an exporter of raw materials to Europe and an importer of European manufactured goods. The transformation of Egypt led to the emergence of a ruling elite composed of large landowners of Turco-Circassian origin and the creation of a class of medium-sized landowners of Egyptian origin who played an increasingly important role in the political and economic life of the country. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990 *]

In the countryside, peasants were dispossessed because of debt, and many landless peasants migrated to the cities where they joined the swelling ranks of the underand unemployed. In the cities, a professional middle class emerged composed of civil servants, lawyers, teachers, and technicians. Finally, Western ideas and cultural forms were introduced into the country. *

Early European Presence in the Middle East and North Africa

As time went on Europe got stronger and richer and began eyeing counties in the Muslim world as sources of raw materials and markets for it goods as outright colonies. The countries that were colonized found their local economies destroyed as their populations were mobilized to produce and consume goods for their mother country — European countries, mostly Britain and France — rather for themselves.

In many ways, the mother country reduced the colonized country to second class status and the people in the mother country began to think of themselves as superior and feel it was their duty to civilize the people in the colony. French and English began replacing Arabic The Arab elite was fascinated by the West. Future kings and generals attended Victoria College in Alexandria where they were trained to be English gentlemen. Many also studied at Oxford, Cambridge and Sandhurst.

Throughout the 19th century the European nations put pressure on the emerging states in North Africa by controlling trade, defining the terms of the trade and forcing the Arab states to become indebted to them so they could demand concessions. European migrants arrived. Many worked for their home government or had business interests. They lived in special enclaves. British, Ottoman and Egyptian actions against slavery and the slave trade finally brought slavery to an end in what was the Ottoman Empire in 1914.

Cotton in Egypt

By 1820, French engineer Louis Jumel discovered a long-staple cotton in his garden in Egypt that proved to be ideal of top-of -the line textiles. From that time forward large and larger amounts of land was turned over to the production of cotton.

The Egyptian cotton industry took off when the supply of cotton from the United States was cut off during the American Civil War in the 1860s.

Textile factories in Lancashire, England were dependent on Egyptian cotton. The cotton was sent to Britain and in some cases was made into finished products that were sent back and sold in the Middle East — a classic example of dependency theory (the notion of resources flowing from a "periphery" of poor and underdeveloped states to a "core" of wealthy states, enriching the latter at the expense of the former).

The cotton boon also lead to population growth as parents wanted to have more children to work the fields and earn money for the family. The profitability of cotton made it more advantageous grow cotton than food

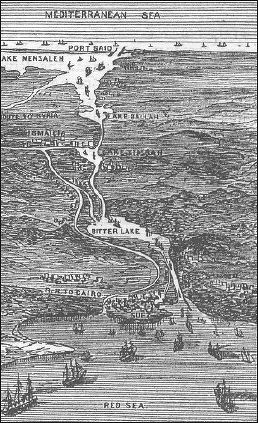

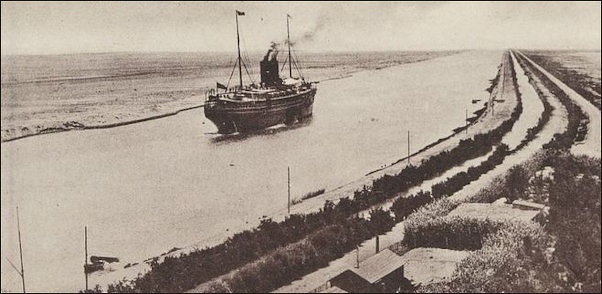

Suez Canal

In 1856 Said Pasha, Muhammad Ali's son, granted a French company the right to build the Suez Canal. The modern Suez Canal (75 miles west of Cairo) is the world's longest large ship canal. Extending from Port Said lighthouse to Suez Roads, it is 162 kilometers (100.8 miles) long and ranges from 302 meters (984 feet) to 365 meters (1,198 feet) wide. It is also the busiest canal in terms of tonnage: 417,852,000 gross tons were registered in 1995.

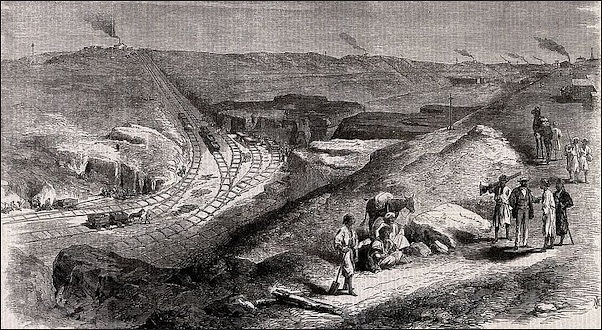

Civil engineering work on the Suez Canal

Connecting the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea, it enables ships traveling between Asia and Europe to avoid going thousands of extra miles around Africa, through the dangerous waters off the Cape of Good Hope. The distance between London and Bombay through the canal is 11,782 kilometers (7,321 miles), compared to 19,878 kilometers (12,352 miles) without it.

Unlike the Panama Canal, the Suez Canal can accommodate all but the largest supertankers. Extending from Port Said on the Mediterranean Sea to Suez on the Gulf of Suez (a branch of the Red Sea), the canal averages 320 yards wide and to 23.5 meters (77 feet) deep. It includes two lakes—the Great Bitter Lake and Little Bitter Lake—and is paralleled by a narrow canal called the Sweet Water Canal. This canal carries water from the Nile to irrigate land on the Sinai peninsula.

Traversing the Suez Canal takes a ship about 14 hours. Ships passes through canal one direction at a time in convoys so that ships going in opposite directions never pass one another within the waterway. The ships wait near Port Said and Suez until it there time to go. The convoys going in opposite directions pass each other in the lakes. To actually navigate the canal all ship captains are required to take on a pilot who is paid a salary and a per boat bonus.

Building the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal was not the first major canal in the region. The ancient Egyptians built one between the Nile and the Gulf of Suez 3,500 years before. This canal was relatively narrow. A canal capable of accommodating ocean-going vessels through the Isthmus of Suez had been a dream of many for centuries but did not become a reality until 1853, when the French diplomat and entrepreneur Ferdinand de Lesseps received permission from his friend Egypt's leader, the Pasha Said, to build it. "Through diplomacy, fiscal sleight-of-hand and technology,” Lesseps was able to realize his dream.

The construction of the canal began in 1859. Over the next ten years, a work force of 1.5 million people, mostly Egyptian laborers, shoveled out 97 million cubic yards of earth and completed the canal. Some 120,000 workers died. After it was finished, Lesseps moved on to Panama but failed in his attempt to make an ocean-linking canal there.

Although the Suez Canal is twice as long as the Panama Canal it was much easier to dig. There were no mountains to breach or locks to build. Most the material that was removed was below-sea-level sand. The only major obstacle was a 50-foot ridge north of Lake Timsah. The final bill was only around $70 million, compared to around $400 million for the Panama Canal. Even so the French had difficulty finding the money, partly because other countries refused too buy shares in the project.

Early History of the Suez Canal

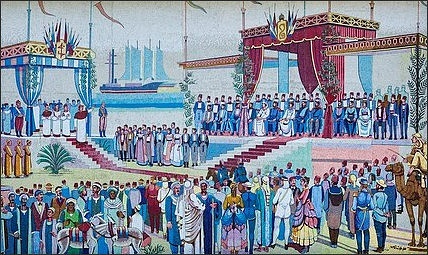

Opening ceremony for the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal opened in 1869. Khedive Ismail (the Turkish viceroy and effective leader of Egypt) hired Verdi to write the opera “Aida” and invited over 1000 Europeans, including Empress Eugénie of France (wife of Napoleon III), the Emperor of Austria, the crown prince of Prussia and the writers Émile Zola and Henrik Ibsen for the opening ceremony. According to a 99-year concession established by the French the canal would be the property of the Suez Company until 1968 when it would be turned over to Egypt. The Suez Company was a private Egyptian corporation with offices in Paris.

The king hosted the first ever joint Muslim-Christian religious service in history, organized a cruise through the canal for the dignitaries, and built a new palace along the canal for the opening party for 5,000 guests who stayed the night. Around 35,000 other guests partied in tents and feasted on roasted sheep outside the palace.

The four-day celebration was so big many guest spent some of their time tracking down lost luggage and looking for their companions. One official commented, "We must be eating up the pyramids stone by stone." The khedive paid for all expenses for his important guests and commissioned a road from the pyramids to the canal so that guests could travel to the celebration. These and other lavish expenditures by the khedive helped bankrupt the country.

Six years after the canal opened it was taken over by the British government, which obtained a £4 million loan from Rothschild to purchase of 176,602 shares of Suez stock (43 percent of all the stock) from the Khedive of Egypt, whose high living and grandiose projects left him desperately in need of cash to pay off his creditors.

Rothschild tipped off British Prime Minister Disraeli about the Khedive's debts. The money was delivered secretly so not to arouse the suspicions of the French. Disraeli presented the canal to the queen as a gift and the British press labeled Rothschild as the Jewish member of the House of Lords who really ran the country.

The French continued to have a stake a in the canal but the shares it received from the king gave the British control. The Anglo-French combine—the Société Universelle du canal Maratime de Suez—continued to own the canal until was nationalized by the Egyptian government in 1956.

European Military Activity in Late 19th Century Egypt

Suez Canal route

Beginning in 1881, the army officers demonstrated their strength and their ability to intimidate the khedive. They began with a mutiny provoked by the anti-Urabist minister of war. Not only were they able to force the appointment of a more sympathetic minister but by January 1882, Urabi joined the government as undersecretary for war.*

These developments alarmed the European powers, particularly Britain and France. Britain was especially concerned about protecting the Suez Canal and the British lifeline to India. In January 1882, Britain and France sent a joint note declaring their support for the khedive. The note had the opposite effect from that intended, producing an upsurge in anti-European feeling, a shift in leadership of the nationalist movement from the moderates in the assembly to the military, and the formation of a new government with Urabi as minister of war. At this point, the goal of Urabi and his followers became not only the removal of all European influence from Egypt but also the overthrow of the khedive.*

In another attempt to break Urabi's power, the British and French agreed on a joint show of naval strength. They also issued a series of demands including the resignation of the government, the temporary exile of Urabi, and the internal exile of his two closest associates, Ali Fahmi and Abd al Al Hilmi. As a result, violent anti-European riots broke out in Alexandria with considerable loss of life on both sides.*

During the summer, an international conference of the European powers met in Istanbul, but no agreement was reached. The Ottoman sultan Abdul Hamid boycotted the conference and refused to send troops to Egypt. Eventually, Britain decided to act alone. The French withdrew their naval squadron from Alexandria, and in July 1882, the British fleet began bombarding Alexandria.*

Following the burning of Alexandria and its occupation by British marines, the British installed the khedive in the Ras at Tin Palace. The khedive obligingly declared Urabi a rebel and deprived him of his political rights. Urabi in turn obtained a religious ruling, a fatwa, signed by three Al Azhar shaykhs, deposing Tawfiq as a traitor who brought about the foreign occupation of his country and betrayed his religion. Urabi also ordered general conscription and declared war on Britain. Thus, as the British army was about to land in August, Egypt had two leaders: the khedive, whose authority was confined to British-controlled Alexandria, and Urabi, who was in full control of Cairo and the provinces.*

In August Sir Garnet Wolsley and an army of 20,000 invaded the Suez Canal Zone. Wolsley was authorized to crush the Urabi forces and clear the country of rebels. The decisive battle was fought at Tall al Kabir on September 13, 1882. The Urabi forces were routed and the capital captured. The nominal authority of the khedive was restored, and the British occupation of Egypt, which was to last for seventy-two years, had begun.*

Urabi was captured, and he and his associates were put on trial. An Egyptian court sentenced Urabi to death, but through British intervention the sentence was commuted to banishment to Ceylon. Britain's military intervention in 1882 and its extended, if attenuated, occupation of the country left a legacy of bitterness among the Egyptians that would not be expunged until 1956 when British troops were finally removed from the country. *

Britain Takes Over Egypt in 1882

With the khedive unable to meet the financial obligations the British began taking steps to limit his power. The khedive responded by creating a Chamber of Deputies led by a army officer to assert Egyptian independence. Britain with the help of France tried to thwart this move by applying diplomatic pressure. When that didn’t work Britain acted alone militarily, and invaded Egypt and seized control of the government in 1882. The British claimed that the Egyptians were revolted against legitimate British aithority and went in to restore order. Few historians see it that way. Most see it as a bold seizure of power based on a flimsy excuse.

With the occupation of 1882, Egypt became a part of the British Empire but never officially a colony. The khedival government provided the facade of autonomy, but behind it lay the real power in the country, specifically, the British agent and consul general, backed by British troops.*

At the outset of the occupation, the British government declared its intention to withdraw its troops as soon as possible. This could not be done, however, until the authority of the khedive was restored. Eventually, the British realized that these two aims were incompatible because the military intervention, which Khedive Tawfiq supported and which prevented his overthrow, had undermined the authority of the ruler. Without the British presence, the khedival government would probably have collapsed.*

In addition, the British government realized that the most effective way to protect its interests was from its position in Egypt. This represented a change in the policy that had existed since the time of Muhammad Ali, when the British were committed to preserving the Ottoman Empire. The change in British policy occurred for several reasons. Sultan Abdul Hamid had refused Britain's request to intervene in Egypt against Urabi and to preserve the khedival government. Also, Britain's influence in Istanbul was declining while that of Germany was rising. Finally, Britain's unilateral invasion of Egypt gave Britain the opportunity to supplant French influence in the country. Moreover, Britain was determined to preserve its control over the Suez Canal and to safeguard the vital route to India.*

steamer traversing the Suez Canal

Between 1883 and the outbreak of World War I in 1914, there were three British agents and consuls general in Egypt: Lord Cromer (1883-1907), Sir John Eldon Gorst (1907-11), and Lord Herbert Kitchener (1911-14). Cromer was an autocrat whose control over Egypt was more absolute than that of any Mamluk or khedive. Cromer believed his first task was to achieve financial solvency for Egypt. He serviced the debt, balanced the budget, and spent what money remained after debt payments on agriculture, irrigation, and railroads. He neglected industry and education, a policy that became a political issue in the country. He brought in British officials to staff the bureaucracy. This policy, too, was controversial because it prevented Egyptian civil servants from rising to the top of their fields.*

Gorst, who was less autocratic than Cromer, had to face a growing Egyptian nationalism that demanded British evacuation from the country. Gorst's attempt to create a "moderate" nationalism ultimately failed because the nationalists refused to make any compromises over independence and because Britain considered any concession to the nationalists a sign of weakness.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994). “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, BBC, Al Jazeera, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018