Home | Category: Medieval Period / Colonialism and Slavery / The Crusades

CRUSADES

The Crusades were a series of military campaigns by the Europeans against Muslims in the Middle East. From the point of view of the Europeans, the First Crusade, in 1099, was successful. The Crusaders captured Jerusalem, inaugurating a two-century-long period of occasional warfare between Muslims and Europeans, many of whom were "Franks" (French). Many Crusaders considered themselves to be military pilgrims and saw the crusade as a form of penance. According to one definition a crudae is "a military expedition summoned by the pope, preached by the clergy, against the infidel, to recover the Holy Land."

A rag tag bunch of European Christians, not pleased with the possession of the Holy Land by infidels, mounted the First Crusade in 1096 and three years later arrived and retook the city after being inspired by a barefoot march around Jerusalem's city walls. Jerusalem was only theirs for a 100 years. The Kurdish warrior Saladin rallied the forces of Islam to retake Islam's third holiest city after Mecca and Medina. The other crusades were unsuccessful from the point of view of the Christians. From the 12th century to the early 20th century the worlds holiest city was possessed by Muslims—namely Mamluk Egyptians and Turks.

There were a total of 10 crusades, and all but the first were unsuccessful for the Christians. In Rhineland (1096), England (1290), and France (1306), Jews were massacred or expelled as part the Crusades movement, and wars were launched by the Catholics against Christian heretics (the Byzantines). On the bright side for the European Christians, commerce with the East expanded during this period of The Crusades, with Venice, thanks in part to Marco Polo and family, whom made their journey to China around the same time as the first crusade, controlling much of the European end of the trade.↕

Islamic History: Islamic History Resources uga.edu/islam/history ; Internet Islamic History Sourcebook fordham.edu/halsall/islam/islamsbook ; Islamic History friesian.com/islam ; Islamic Civilization cyberistan.org ; Muslim Heritage muslimheritage.com ; Brief history of Islam barkati.net ; Chronological history of Islam barkati.net

Reasons for the Crusades

The stated purpose of the Crusades was to reclaim Jerusalem, from the Muslims, and was seen as a massive counter-offensive by European Christians to stop the Muslims take over of the Holy Land (mainly Israel and Palestine) and reverse the tide of Muslim advancement against Christian territories. Augustine's concept of a just and holy war (possibly influenced by Islam's concept of the holy war, "jihad") was promulgated.

Carl A. Volz wrote: “Ever since the fall of Jerusalem to Islam in 638 Christians in the West had considered the possibility of a counter-offensive to recapture the Holy Places. The crusading ideal did not emerge first in 1098, but was appealed to by popes Leo IV, John VIII, Sylvester II, and Gregory VII. Even before the first crusade was launched, Spain offered a fertile opportunity for fighting Islam, and a number of expeditions were made there in the eleventh century. [Source: Carl A. Volz, late professor of church history at Luther Seminary, The Apostolic Fathers. web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu /~]

"The Crusades," wrote historian Daniel Boorstein, "would be one of the most miscellaneous, most unruly movements in history." Mobs led by charismatic figures like Peter the Hermit, who ironically was a gregarious rebel rouser, and Walter the Penniless raped and pillaged their way toward the Holy City. "All the West and all the barbarian tribes beyond the Adriatic," reported a Byzantine princess, "were moving in a body through Europe towards Asia, bringing whole families with them." There were even reports that the Crusaders roasted tender Christian babies to feed themselves along the way. [Source: “The Discoverers” by Daniel Boorstin]

The Crusades was one way for Europeans to focus attention away from their problems at home. Potentially rebellious peasants in particular were mobilized to throw the Muslims out of Jerusalem. Merchants supported The Crusades as a way to claim trade royalties and ports. Many Christians believed that coming of the year 1000 indicated that the second coming of Christ was near and the this led to the sense of immediacy in taking Jerusalem.

Beginning of the Crusades

Pope Urban II and the Council of Clemont

The Crusades began with the declaration of a Holy war by the Byzantines against the Muslims and a request by the Emperor of Byzantine in 1095 for military aid from Pope Urban II (1035-1099) to help reclaim the Holy Land. The Catholic Church at this time was corrupted by the buying and selling of pardons and Urban saw the request as an opportunity to clean up his church and unify the Byzantine and Catholic churches, which had fairly recently split. A council held in the south of France to discuss The Crusades attracted such large crowds Urban had to make his speech in a large field because there wasn't enough room in the cathedral. [Source: “The Discoverers” by Daniel Boorstin]

Carl A. Volz wrote: “In 1055 Bagdad (ruled by the Abbasid Muslims under the Caliph) was occupied by the Seljuk Turks, and the Caliph became a mere figurehead. The Seljuks expanded, and in 1071 they defeated the Byzantine forces at the important battle of MANZIKERT. By 1077 the Turks had captured Nicea. In 1071 Jerusalem was taken by them, and Christian entree to the Holy Places, permitted under the earlier Muslims, was now either prohibited, or pilgrims were harassed. The eastern emperor, Alexius Comnenus, appealed to the pope for military aid to recover Nicea. [Source: Carl A. Volz, late professor of church history at Luther Seminary, The Apostolic Fathers. web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu /~]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Most historians consider the sermon preached by Pope Urban II at Clermont-Ferrand in November 1095 to have been the spark that fueled a wave of military campaigns to wrest the Holy Land from Muslim control. Considered at the time to be divinely sanctioned, these campaigns, involving often ruthless battles, are known as The Crusades. At their core was a desire for access to shrines associated with the life and ministry of Jesus, above all the Holy Sepulcher, the church in Jerusalem said to contain the tomb of Christ (2005.100.373.100). Absolution from sin and eternal glory were promised to the Crusaders, who also hoped to gain land and wealth in the East. Nobles and peasants responded in great number to the call and marched across Europe to Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine empire. With the support of the Byzantine emperor, the knights, guided by Armenian Christians (57.185.3), tenuously marched to Jerusalem through Seljuq-controlled territories in modern Turkey and Syria. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

Pope Urban II's call to arms for The Crusades was much grander than anything a secular ruler could have put together. Other pontiffs talked about doing something to liberate the Holy Land, but Pope Urban II was the first to really do something about it. His followers went from city to city causing religious frenzy and had particular success atracting younger sons not in line to inherit property.

Pope Urban II's Call

Answering the Call to participate in the Crusades

In 1095, Pope Urban II (1035-1099) issued the call for The Crusades First II at the Council of Clermont, proclaiming, "Come forward to the defense of Christ...Wrest [Jerusalem] from the evil race, and keep it for yourself." Pope Urban II promised a remission from sins for all Crusaders and declared: "Enter upon the road to the Holy Sepulcher, rest the land from a wicked race, and subject it to yourselves. Jerusalem is a land fruitful above all others, a paradise of delights. The royal city, situated at the center of the earth, implores you to hear her aid."

Urban's speech was recorded by Robert the Monk. "Jerusalem is the navel of the world," the pope said. "This is the land which the Redeemer of mankind illuminated by his coming, adorned by his life, consecrated by his passion, redeemed by his death, and sealed by his burial...This royal city...is now held captives by his enemies and is made a servant, by those who know not God, for the ceremonies of the heathen...It looks to you for help...Undertake this journey, therefore, for the remission of your sins, with the assurance of glory which can not fade."

Carl A. Volz wrote: “The pope was the only recognized leader in the West with the authority and prestige to call a crusade. In 1095 national states were not yet powerful or centralized. Not a single king participated in the First Crusade. The promise of an indulgence, likewise, was only the pope's to give. Papal support lended credibility to the concept of a just and holy war. The Crusader's vow placed him and his property and loved ones under papal protection. Feudal states provided the armies. The Crusades did much to enhance papal prestige, or the prestige of the leaders. In later crusades led by kings, popes were notably unenthusiastic (4th Crusade, Frederick II). [Source: Carl A. Volz, late professor of church history at Luther Seminary, The Apostolic Fathers. web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu /~]

In his speech at Clermont in 1095, Pope Urban II gave as his reasons for the Crusades: 1) the recovery of the Holy Land; 2) the healing of the East-West schism the establishment of peace in Western Europe (NB Europe had just emerged from the devastating Investiture Controversy, and civil war was still endemic. The pope suggested both sides combine their forces to fight the infidel instead of each other. The Crusades thus served as a catharsis for the West.); /~\

In his speech he promised: 1) military assistance to the Greeks; 3) delivery of the Holy Places; 4) indulgences and eternal rewards (first plenary indulgence); and 5) material reward. His speech concluded with the war cry, “Deus Vult!” — It is God's will! /~\

Crusaders

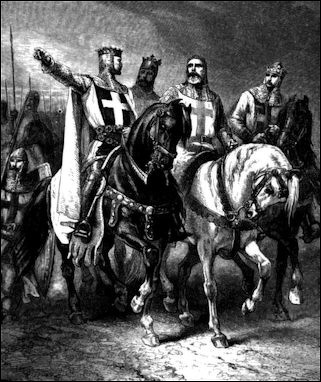

Crusade leaders

Many Crusaders went to the Holy Land for religious and noble reasons. Others went to get rich. Other still went to have their sins forgiven. In the early 12th century, half the knights in France went on The Crusades and they were joined by a large number of knights from England, Spain and what is now Germany.

The scallop shell became a symbol of Western Christendom when Crusaders picked up “Pecten jacabaeus “shells on the Palestine coasts as a souvenir that proved they were there. If you see a statue of a saint with a scallop shell in the brim of his hat or on his purse, most likely it is Saint James. Today the coat of arms of many aristocratic families, including that of Winston Churchill, are decorated with a scallop shell. [Source: Paul Zahl Ph.D., National Geographic, March 1969]

Some knights sold their property and gave up their families and homes to take part in . Participation in The Crusades increased by the establishment of primogeniture laws which meant that young landless knights had to find a new way to make their fortune.

Many of the knights were mounted on massive Clydesdale-like heavy horses, the equivalent of tanks in medieval warfare. After some battles it was said these horses "bristled with arrows like pin cushions" and were ready to fight again the next day. Horses that died on the way to Jerusalem were mainly the victims of starvation. One Danish prince who tried to walk barefoot from Europe to Jerusalem in the 11th century as penance for participating in a murder died of exposure on the way there. ♂

The bodies of Crusaders that died on route were dismembered and boiled so their bones could be sent back to Europe for a burial in the Crusader's homeland. The practice became so common that Pope Boniface VIII issued a papal bull prohibiting it.

Military Orders

Carl A. Volz wrote: “After the first wave of the First Crusade, the so-called Military Orders became organized: 1) Hospitalers (Knights of St. John the Baptist), actually originated about 1070 to assist pilgrims enroute to Jerusalem. They established hospices and saw to the physical well-being of travelers. 2) Knights Templar were organized about 1118 by Humh of Payen, and given a Rule by Bernard of Clairvaux (De Laude Nove Militiae). Both Orders were directly under the pope. After 1291 (Fall of Acre and end of crusades) the Templars removed to Cyprus and Hospitallers to Rhodes and Malta. Templars became international bankers, aroused the hostility and envy of many, and were finally dissolved by King Philip IV of France in 1314 (Jacques de Molay was their last Master). 3) Teutonic Knights are from the 3rd Crusade, founded by Herman von Salza. Were of little consequence to The Crusades, but it was they who expanded Germany to the East, and are considered the founders of Prussia (Brandenberg). [Source: Carl A. Volz, late professor of church history at Luther Seminary, The Apostolic Fathers. web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu /~]

Knights were often landowners whose sole occupation othet than managing their land was warfare. They were trained in hand to hand combat. When they weren’t fighting they participated in tournaments. Unattached ("freelance") knights didn’t own any land and answered to a lord. They distinguished themselves through acts of valor and their fighting skills.

The Teutonic Knights emerged in medieval German, when, the British historian James Bryce wrote, "every floodgate of anarchy was opened — prelates and barons extended their domains by war: robber-knights infested the highways and the rivers: the misery of the weak, the tyranny and the violence of the strong, were such as had not been seen for centuries." The Teutonic Knights were often more barbaric the people they fought. Early Teutonic kings like Sigurd the Generous were like "big men" and "great providers." The motto of the Teutonic Knights was "the sword is our pope."

The Knights of St. John (later named the Knights of Malta) is the longest surviving Crusading Order from the Middle Ages. It began as a hospital service on the island of Rhodes (now part of Greece) to help Christians pilgrims who became ill while visiting the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Later the group helped Crusaders returning from holy war against the Muslims in Palestine. It was only later that the Knights of St John became know for their military prowess.

Pilgrims were the medieval equivalent of tourists. There were guides in the holy cities to show them around and inns spaced a day's journey apart on the pilgrim routes to provide food and accommodation. The pilgrims were blessed by priests in the home town before they left and they carried a staff and a seashell (the symbol of a pilgrim, and later a Crusader) and wore a flat crowned hat with a patch showing their destinations. Bandits and pirates preyed on pilgrims, and organizations like the Knights of St. John were set up later to protect them.∞

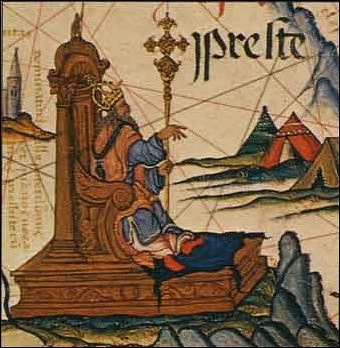

Prester John

During the Crusades, rumors began to be spread about a great Christian king in the East named "Prester" John, whom some said descended from the Three Wise Men who visited Bethlehem. Prester John reportedly defeated the Persians and was on his way to help the Crusaders. Marco Polo said that Prester John was killed in a great battle with Genghis Khan. [Source: "Don't Know Much About Geography" by Kenneth Davis, William Morrow & Co.]

Many of the early European explorers to Asia and Africa were hoping to meet up with Prester John, a mythological priest-king who resided somewhere in the East and was supposed to help the Crusaders reclaim Jerusalem. Portuguese explorers went looking for him up the Senegal and Congo Rivers in Africa. Maps from the late 16th century had the kingdom of Prester John located in present-day Ethiopia. Some of the first Europeans to venture on the Silk Road traveled east towards Central Asia and China looking for him. The legend of Prester John is believed to have originated with Saint Thomas, an Apostle of Christ said to have traveled to India in the A.D. first century. More miracles have been attributed to Saint Thomas than any other saint. Additionally, stories of Ung Khan (Unc Chan) — a Mongol ruler who preceded Genghis Khan and who may have been a Nestorian Christian — may have made their way to Europe, placing Prester John in Central Asia.

Prester John

The 13th-century Silk Road Explorer William of Rubruck wrote: “At the time when the Franks took Antioch the sovereignty of these northern regions belonged to a certain Con cham. Con was his proper name, cham his title, which means the same as soothsayer. All soothsayers are called cham and so all their princes are called cham, because their government of the people depends on divination. Now we read in the history of Antioch, that the Turks sent for succor against the Franks to King Con cham; for from these parts came all the Turks. That Con was of Caracatay. Now Cara means black, and Catay is the name of a people, so Caracatay is the same as "Black Catay." And they are so called to distinguish them from the Cathayans [=Chinese] who dwell by the ocean in the east, and of whom I shall tell you hereafter. Those Caracatayans lived in highlands (alpibus) through which I passed, and at a certain place amidst these alps dwelt a certain Nestorian, a mighty shepherd and lord over a people called Nayman, who were Nestorian Christians. [Source: “The Journey of William of Rubruck to the Eastern Parts of the World, 1253-55" by William of Rubruck, translation by W. W. Rockhill, 1900; depts.washington.edu/silkroad /~]

“When Con cham died, that Nestorian raised himself to be king (in his stead) and the Nestorians used to call him King John [presumably Prester John], and to say things of him ten times more than was true. For this is the way of the Nestorians who come from these parts: out of nothing they will make a great story, just as they have spread abroad that Sartach is a Christian, and so of Mongke Khan and Güyük Khan [Genghis Khan's grandson Güyük Khan (d.1248)], because they show more respect to Christians than to other people; though of a truth they are not Christians. So great reports went out concerning this King John; though when I passed through his pasture lands, no one knew anything of him save a few Nestorians. On those pasture lands lived Güyük Khan, to whose court went Friar Andrew, and I also passed through them on my way back. This John had a brother, also a mighty shepherd, whose name was Unc [=Ong Khan]; and he lived beyond the alps of the Caracatayans, some three weeks journey from his brother, and he was lord of a little town called Caracarum [=Qaraqorum. Karakorum], and the people he had under his rule were called Crit and Merkit, and they were Nestorian Christians. But that lord of theirs had abandoned the worship of Christ, and had taken to idolatry, having about him priests of the idols, who are all invokers of demons and sorcerers. Beyond those pasture lands, some ten or fifteen days, were the pasture lands of the Mongol, who were very poor people, without a chief and without religion except sorcery and soothsaying, such as all follow in those parts." /=\

Crusader Castles and Constantinople

Constantinople, present-day Istanbul, was the capital of Christian Byzantium and was both a place to avoid, as the Orthodox Christians there were regarded as rivals as Catholics from Europe, and a gathering place for Christians as they transitioned from Christian lands to Muslim ones in what are now Turkey, Syria and Palestine. "Oh what a great and beautiful city is Constantinople!" wrote a Crusader chaplain in 1097, "How many churches and palaces it contains fashioned with wonderful skill. It would be tedious to enumerate what kind of wealth there is of every kind, of gold, or silver...of holy relics." There many Crusader Castles near the coast of Syria. With the capture of Antioch in 1098, the Crusaders ruled the Mediterranean coast from northern Syria to the Red Sea. During the Crusades of the 11th, 12th and 3th century, Europeans controlled much of the Syrian coast were they constructed a network of magnificent castles that still are scattered across the landscape between the Mediterranean and the desert. Occupying the castles were historical figures—such as Richard the Lion Hearted, Louis IX of France and Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa— and warrior monks—like the white-coated Knights of Templar, the scarlet red Knights of St. John of the Hospital and the Order of Lazarus, made up almost entirely of knights with leprosy.

Establishment of castles during The Crusades helped make the Mediterranean safe for European vessels. Money generated fueled the wars fought between sea powers like Venice, Pisa and Genoa, and banking and overland trade powers like Florence and Milan. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

In Turkey there are several castles, most notably in Bodrum, that were built during The Crusades. These castles were positioned along the overland and sea crusade routes, offering protection, lodging and medical care for the Crusaders. Organizations that ran the hospitals and protected the castles, like the Knights of St. John, became as powerful as nations.

Knights of Malta (St John) in Rhodes, an island in present-day Greece

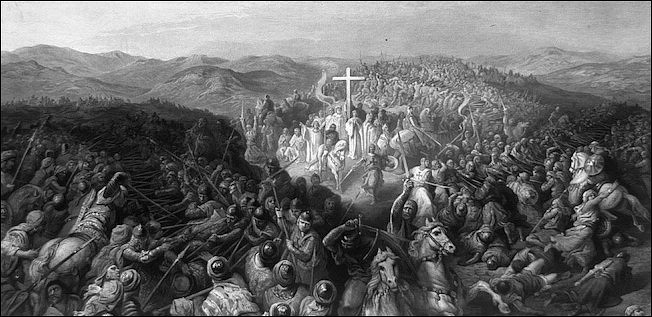

Crusades Fighting

The Crusades to some degree were never thought as anything more than a border problem among the Muslim Arabs and Turks, especially after Jerusalem was recaptured by Saladin. Even though the Crusaders were a formidable, armored fighting force they were unable to transport and maintain enough manpower in the Holy Land to replace the men who died of battlefield wounds but mostly malaria and other diseases. [Source: Robert Wernick, Smithsonian magazine, September 1986]

Face-to-face knight tactics were matched against hit-and-run tactics of the Turks and the horsemen employed by the Arabs. Muslims won out due to superiority in numbers and their ability to return and fight another day. The knights were used to charging armies that stood and fought back, not ones that ran away and harassed them with arrows from safe distances. Armor protected the soldiers, but also slowed them down. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

European medieval battles often only lasted a couple of hours. These battles often involved two armies of a few hundred to a few thousand men who lined up a few hundred yards from each other and fired arrows at each other. When the arrows ran out they charged each other for hand to hand combat until the leaders were killed or captured.

Describing the capture of Acre, the chronicler Richard of Devizes wrote: "As soon as he sun rose, the bowman...kept up an unceasing rain of arrows on the Turks and Thracians. The stone throwers. skillfully placed, broke down the walls by repeated shots. Even more effective than these were miners, who opened a way for themselves underground and dug under the foundations of the walls...The king himself ran around through the ranks, ordering, exhorting nd inspiring."

Crusaders often had their friends promised to dismember and boil them if they died and send their bones to their homes. Afterwards the church passed rules prohibiting dismemberment, which greatly hampered medical research.

Medieval European Warfare

Warfare in the Middle Ages was defined by a code of honor and rigid system of military law that was respected more than the Geneva convention is today. Often described as chivalry today the rules were unwritten and customary but were sometimes defined by official ordinances and decrees. There were strict rules on the granting of quarter—how one knight surrenders to another—and how the knight was expected to be treated after the surrender. The whole system of warfare was based on how much ransom a knight could expect to receive from the knight he captured. The incentive therefore was for knights to be captured alive and the wealthier they were the higher ransom could be expected.

Over time the system began to break down. Technological advances in archery and later artillery led to decline in face-to-face combat, which in made it more difficult to capture enemy knights and hold them for ransom. The system also was affected by the Crusades and the Reformation. Afterwards the enemies were longer regarded as Christian equals but rather as infidels that did not deserve equal treatment.

Medieval warfare usually centered around capturing fortresses, castles or walled cities or towns. If a city refused to surrender and ultimately was captured, the common policy was to kill the men and sell the women and children were sold into slavery. Noblemen were ideally captured and declared traitors. They were beheaded and their land was seized as divided among the conquerors.

Medieval European Weapons

Medieval European Knights wore armor and chain mail for protection, held a shield in one hand, and wielded a sword, lance, battleaxe, mace or some other such weapon with the other hand. Knights believed it was cowardly to shrink from a blow, and many died needlessly. Jousting was something that made for an interesting sport but had little application to real battles. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

Battle of Ascalon

Both side used crossbows for accuracy, longbows for distance, missiles and stones when the enemy was at hand and pikes, axes and swords for close range fighting. The weapon of choice from the late Middle Ages until the gun was commonly used was the pike. Swiss mercenaries were particularly skilled pikesmen. During the "mad battle" of St. Jacob-en-Birs (1444) a group of 1,500 Swiss pikesmen battled an army of 30,000 and fought until every one was dead.

In the Middle Ages swords began taking on a variety of forms, each with its purpose and advantages and disadvantages. Medieval knights favored heavy machete-like blades which enabled them to crack open their opponents armor. Maces, large club-like staffs, were also used to break armor.

Long bows were perfected by the English, who used them to fire arrows in high, arching trajectories at enemies up to several hundred meters away. Crossbows were introduced around 11th century. Archers often ran out of arrows. When they did they collected arrows fired at them by the enemy and shot them back. Medieval weapons also included giant crossbows that were cranked up with winches and giant 150-foot-high rolling staircase — similar the stairs used to unload airline passengers — that carried a hundred or so soldiers to the castle wall.

Attacking and Defending Fortresses

Attackers of castles used ladders, catapults, battering rams to breach the walls. The defenders often poured boiling oil, black pitch, waters and sometimes even hot soup on the storming parties that attempted to surmount the walls. Castle stairs were often built so they could easily be destroyed during an attack and entrances were positioned that defenders could hurl stones or boiling il on them. ["Life in a Medieval City" by Joseph and Frances Gies, Harper Perennial]

Since time was of essence attackers usually concentrated their resources into one massive assault. Ladders and towers planted on wooden platforms placed in the moats and ditches were employed in attempts to surmount the walls and catapults, or siege weapons were used to knock down the walls or gates. The attackers usually sustained many more casualties than the defenders because the attackers were usually out in the open and the defenders had walls and towers to hide behind. Attackers often employed unusua tactics. During one 13th century battle the Florentines besieged Siena catapulted excrement and dead, decaying donkeys over the fortress walls in effort to start the plague. ["Life in a Medieval City" by Joseph and Frances Gies, Harper Perennial]

Defenders usually could fend off an assault by concentrating their manpower at the point of attack. Castles and ramparts usually had round towers because they gave the defenders more angles to shoot at the attackers. In medieval Europe, the Swiss were very good at repelling invaders. The rolled boulders on to them, knocked them off of their horses with halberds and then clubbed them to death with battleaxes.

Perhaps the most effective way to breach a wall was a technique called "mining" in which the attackers dug a huge tunnel under the main keep or the part of the wall they wanted to knockdown. The mine was "discharged" when the timbers that held up the tunnels were set on fire, causing the ground underneath the fortification to give way. Sometimes the attackers showed their mines to engineers on the defending side. If the engineers thought the mine was constructed well enough to cause the fortress to collapse sometimes the defenders surrendered. More often they "contermined" by building their own tunnels, attacking the defenders underground and building palisades to sure up the walls they knew were going to be mined. ["Life in a Medieval City" by Joseph and Frances Gies, Harper Perennial]

Muslim Response to the Crusaders

According to Encyclopedia.com: Throughout this period, the Muslim response to the Crusaders was weakened by internal fighting and rivalry. The Egyptian Muslims, a Shiite dynasty called the Fatimids (who believed that they were the descendants of Muhammad's daughter Fatima), hated Turkish Sunni Muslims. The Turkish Muslims themselves were divided into two factions or clans, the Seljuks and the Danishmends. Many Muslim leaders in Palestine and throughout Arabia were more interested in maintaining control over their small domains than they were in loyalty to the caliphate in Baghdad, so at various times they cooperated with the Crusaders. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

In 1090 a rebel group called the Ismailis formed to oppose the Abbasid Baghdad regime. This group, which came to be called the Assassins (a Western term possibly from the word hashish, the drug that members used before carrying out their missions), vigorously opposed Sunni Islam. They were also enemies of the Shiites in Egypt, who had expelled them and driven them underground. To undermine (weaken or ruin) Sunni Islam, the Assassins frequently cooperated with the Crusaders and assassinated Muslim leaders.

The major Crusades ended in 1291, when Muslim forces drove the Crusaders out of their last stronghold at Acre in Palestine. During the Crusades, one of the great heroes of Islam emerged. This was Saladin (1137–1193), the name commonly used to refer to Salah al-Din, a general who was able to unite Muslim forces and oppose the Franks during the Third Crusade (1189–92).

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Crusades map, Google sites

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994). “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, BBC, Al Jazeera, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024