Home | Category: Sumerians and Akkadians

SUMERIAN THEOCRATIC GOVERNMENT

Stela of Ur-Nammu Sumer was a theocracy with slaves. Each city state worshiped its own god and was ruled by a leader who was said to have acted as an intermediary between the local god and the people in the city state. The leaders led the people into wars and controlled the complex water systems. Rich rulers built palaces and were buried with precious objects for a trip to the afterlife. A council of citizens may have selected the leaders.

Some scholars have described the Mesopotamian system of government as a "theocratic socialism." The center of the government was the temple, where projects like the building of dikes and irrigation canals were overseen, and food was divided up after the harvest. Most Sumerian writing recorded administrative information and kept accounts. Only priests were allowed to write.

Early Sumerians established a powerful priesthood that served local gods, who were worshiped in temples that dominated the early cities. Much of political and religious activity was oriented towards gods who controlled the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and nature in general. If people respected the gods and the gods acted benevolently the Sumerians thought the gods would provide ample sunshine and water and prevent hardships. If the people went against the wishes of the local god and the god was not so benevolent: droughts, floods, famine and locusts were the result.

In Uruk kings took part n important religious rituals. One vase from Uruk shows a king presenting a whole set of gifts to a temple of the city goddess Inana. Kings supported temples and were expected to turn over some of the booty from wars and raids to temples.

Some have called Sumer the epitome of the welfare city-state. Sam Roberts in the New York Times, “Work was a duty, but social security was an entitlement. It was personified by the Goddess Nanshe, the first real welfare queen immortalized in hymn as a benefactor who “brings the refugee to her lap, finds shelter for the weak.”... Nanshe, the Mesopotamian goddess, was hailed by some bards of Sumer for her compassion and, undoubtedly, denounced by others as a dupe." [Source: Sam Roberts, New York Times, July 05, 1992]

Categories with related articles in this website: Mesopotamian History and Religion (35 articles) factsanddetails.com; Mesopotamian Culture and Life (38 articles) factsanddetails.com; First Villages, Early Agriculture and Bronze, Copper and Late Stone Age Humans (50 articles) factsanddetails.com Ancient Persian, Arabian, Phoenician and Near East Cultures (26 articles) factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources on Mesopotamia: Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; Mesopotamia University of Chicago site mesopotamia.lib.uchicago.edu; British Museum mesopotamia.co.uk ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Louvre louvre.fr/llv/oeuvres/detail_periode.jsp ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology penn.museum/sites/iraq ; Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago uchicago.edu/museum/highlights/meso ; Iraq Museum Database oi.uchicago.edu/OI/IRAQ/dbfiles/Iraqdatabasehome ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Oriental Institute Virtual Museum oi.uchicago.edu/virtualtour ; Treasures from the Royal Tombs of Ur oi.uchicago.edu/museum-exhibits ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org

Archaeology News and Resources: Anthropology.net anthropology.net : serves the online community interested in anthropology and archaeology; archaeologica.org archaeologica.org is good source for archaeological news and information. Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com features educational resources, original material on many archaeological subjects and has information on archaeological events, study tours, field trips and archaeological courses, links to web sites and articles; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org has archaeology news and articles and is a publication of the Archaeological Institute of America; Archaeology News Network archaeologynewsnetwork is a non-profit, online open access, pro- community news website on archaeology; British Archaeology magazine british-archaeology-magazine is an excellent source published by the Council for British Archaeology; Current Archaeology magazine archaeology.co.uk is produced by the UK’s leading archaeology magazine; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com is an online heritage and archaeology magazine, highlighting the latest news and new discoveries; Livescience livescience.com/ : general science website with plenty of archaeological content and news. Past Horizons : online magazine site covering archaeology and heritage news as well as news on other science fields; The Archaeology Channel archaeologychannel.org explores archaeology and cultural heritage through streaming media; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu : is put out by a non-profit organization and includes articles on pre-history; Best of History Websites besthistorysites.net is a good source for links to other sites; Essential Humanities essential-humanities.net: provides information on History and Art History, including sections Prehistory

Sumerian Language

Uruk Plate John Alan Halloran of sumerian.org wrote: “There appears to be some slight relation between Sumerian and both Ural-Altaic and Indo-European. This may just be due to having evolved in the same northeast Fertile Crescent linguistic area. I don't see any connection at all between Sumerian and Semitic. [Source: John Alan Halloran, sumerian.org]

Many cuneiform tablets are written in Akkadian. “Speakers of the Sumerian language coexisted for a thousand years with speakers of 3rd millennium Akkadian dialects, so the languages had some effect on each other, but they work completely differently. With Sumerian, you have an unchanging verbal root to which you add anywhere from one to eight prefixes, infixes, and suffixes to make a verbal chain. Akkadian is like other Semitic languages in having a root of three consonants and then inflecting or conjugating that root with different vowels or prefixes.”

On different Sumerian dialects, “There is the EME-SAL dialect, or women's dialect, which has some vocabulary that is different from the standard EME-GIR dialect. Thomsen includes a list of Emesal vocabulary in her Sumerian Language book. The published version of my Sumerian Lexicon will include all the variant Emesal dialect words. Emesal texts have a tendency to spell words phonetically, which suggests that the authors of these compositions were farther from the professional scribal schools. A similar tendency to spell words phonetically occurs outside the Sumerian heartland. Most Emesal texts are from the later part of the Old Babylonian period. The cultic songs that were written in Emesal happen to be the only Sumerian literary genre that continued to be written after the Old Babylonian period.”

Language and Writing at the Time of the Sumerians

Inscriptions from Ur

In addition to the Sumerians, who have no known linguistic relatives, the Ancient Near East was the home of the Semitic family of languages. The Semitic Family includes dead languages such as Akkadian, Amoritic, Old Babylonian, Canaanite, Assyrian, and Aramaic; as well as modern Hebrew and Arabic. The language of ancient Egypt may prove to be Semitic; or, it may be a member of a super-family to which the Semitic family also belonged. [Source: Internet Archive, from UNT]

There were also "The Old Ones," whose languages are unknown to us. Some presume their speech ancestral to modern Kurdish, and Russian Georgian, and call them Caucasian. Let's call these peoples Subartu, a name given to them after they were driven northward by the Sumerians and other conquerors of Mesopotamia.

Indo-Europeans spoke languages ancestral to all modern European languages except Finnish, Hungarian, and Basque. It was also ancestral to modern Iranian, Afghan, and most of the languages of Pakistan and India. They were not native to the Near East, but their intrusions into the area made them increasingly important after 2500 B.C.. F.

Though writing is still presumed to have evolved in Mesopotamia, it seems likely that the pre-Sumerian inhabitants of the valley, and not the Sumerians themselves, were the first to use it there. New evidence from Egypt re-opens the possibility that Egyptians may have started writing as early as the Mesopotamians. By 2400 B.C. writing was in use throughout the Near East from Harappan India westward, possibly as far as the Mediterranean island of Crete. Do not interpret this to mean that everyone within the described area knew how to read and/or write. To the contrary, the vast majority of the peoples who lived before A.D. 1900 never learned reading and writing. Because literacy was so narrowly confined to a small elite of lords and scribes, it was easy for entire civilizations to lose literacy. Such a loss was experienced by India from about 1700 B.C. to 1000 B.C., and by the peoples of Turkey and the Aegean area from 1200 to 800 B.C..

First Sumerian Writing

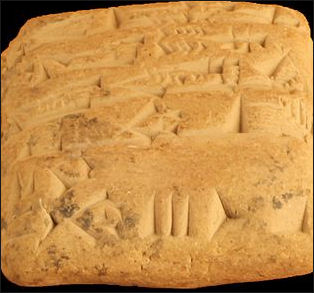

Akkadian language cuneiform

The Sumerian are credited with inventing writing around 3200 B.C. based on symbols that showed up perhaps around 8,000 B.C. What distinguished their markings from pictograms is that they were symbols representing sounds and abstract concepts instead of images. No one knows who the genius was who came up with this idea. The exact date of early Sumerian writing is difficult to ascertain because the methods of dating tablets, pots and bricks on which the oldest tablets with writing were found are not reliable.

By around 3200 B.C., the Sumerians had developed an elaborate system of pictograph symbols with over 2,000 different signs. A cow, for example, was represented with a stylized picture of a cow. But sometimes it was accompanied by other symbols. A cow symbols with three dots, for example, meant three cows.

By around 3100 B.C., these pictographs began representing sounds and abstract concepts. A stylized arrow, for example, was used to represent the word "ti" (arrow) as well as the sound "ti," which would have been difficult to depict otherwise. This meant individual signs could represent both words and syllables within a word.

The first clay tablets with Sumerian writing were found in the ruins of the ancient city of Uruk. It is no known what the said. They appear to have been list of rations of foods. The shapes appear to have been based on objects they represent but there is no effort to be naturalistic portrayals The marks are simple diagrams. So far over a half a million tablets and writing boards with cuneiform writing have been discovered.

Cuneiform writing remained the dominant form of writing in Mesopotamia for 3,000 years when it was replaced by the Aramaic alphabet. It began mainly as a means of keeping records but developed into a full blown written language that produced great works of literature such as the Gilgamesh story.

Sumerian Culture and Art

In the period before 2700 B.C., the Sumerians considered most of their kings to be gods, or at least heros. The Deification and Heroization of kings mostly ceased after Gilgamesh, king of Uruk around 2700 B.C.. The Gilgamesh of the epic was predominantly an Heroic, but tragic, figure. He was no god. Some early Sumerian tales about Gilgamesh make him appear ambivalent. He was not a great king. The story, "Gilgamesh and Agga of Kish," shows him forced to acknowledge the overlordship of the Great King of Kish, possibly Mesannepada of UR.

ram in a thicket The Sumerians created lovely alabaster vases with carved heads, alabaster and stone figurines, cylinder seals made with precious stones, gold ornaments, gold jewelry and musical instruments decorated with gold and semi-precious stones. The were expert metal workers adept at fashioning silver and gold. An inlaid gold vessel in the form of an ostrich egg might have held food and drink.

Most of the Sumerian works of art have been excavated from graves. The Sumerians often buried their dead with their most prized objects. They also produced some of the first portraits. Gudea, the Sumerian king of Lagash, who lived around 2100 B.C., is remembered with a series of seated sculptures that are among the most famous Sumerian works of art. A life size one made of black diorite is particularly nice.

Much of the stuff found by Sir Leonard Woolley’s excavations at Ur is now in the British Museum. Some is at the Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. One of the most famous objects there is Great Lyre from the King’s Grave. It is a gold-and-lapis-lazuli bull’s head and inlaid shell plaque attached to a re-created wooden frame.

The soundbox of a lyre unearthed in a grave in Ur, dated at 2700 B.C., contains an amusing comic-book-like rendering of animals made with a mosaics of shell, gold, and silver on a background of lapis lazuli. The image is believed to a depiction of a poplar fable. A finely carved gypsum head of an unknown subject, dated 2097 to 1989 B.C., features eery eyes colored with blue pigments.

Sumerian Warfare

There was virtually no evidence of warmaking in the early years of Sumer. Between 3100 B.C. and 2300 B.C. warfare started to play a bigger role in city-state relations as priest-kings were replaced by warlords with armies armed with lance and shields. Military tactics were developed, weapons started utilizing metals and the first "battles" begun taking place.

There is evidence that the king of Uruk went on military campaigns to bring back cedar wood from the mountains as early as early as 2700 B.C. and by 2284 B.C. Sumerian kings were fighting wars with neighboring cities and peoples like the Semites. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

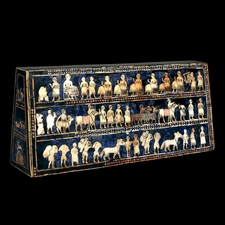

The earliest evidence of state-sponsored warfare is an inscribed stele, dated to 2500 B.C., found at Lagash (also known as Telloh or Ginsu). It described a conflict between Lagash and Umma for irrigation rights and was settled in a battle in which war wagons were used. The Standard of Ur, a Sumerian object dated to around 2500 B.C. included images of warfare with wheeled vehicles and warriors. The vehicles looked more like transport vehicles than a fighting ones.

Sumerian Warfare Tactics, Prisoners and Spies

Around 2500 B.C. soldiers started wearing metal helmets and organizing themselves into columns with a six man front. They wore cloaks and tunics that appeared to be strengthened with metal, and used four-wheeled carts driven by four horses (prototypes of armor and chariots). The even employed "death pits" in which enemies where lured into battlefield equivalents of holes with trapdoors where they picked off like proverbial sitting ducks. [Source: “History of Warfare” by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

The primary weapons were lances and shields. By the middle of the second millennium the Sumerians had developed the sophisticated composite bow and utilized method of siege craft (breaching and scaling) to attack fortresses. The results could sometimes be quite bloody. A 4500-year-old inscription from Lagash describes piles of bodies with as many as a thousand enemy corpses. The Mesopotamians also used psychological warfare to defeat their enemies. [Ibid]

Prisoners of war were not used as slaves but were deported to differents part of the kingdom. Sometimes they were sacrificed in temples. It seems only men were killed in battles and sieges and in sacrificial rites not women or children. Historian Ignace Gelb has argued that this was so because it was "relatively easy to exert control over foreign women and children" and "the state apparatus was still not strong enough to control masses of unruly male captives." As the power of the state increased males prisoners were "marked and branded" and "freed and resettled" or used as mercenaries or bodyguards to the king.

Spies were called scouts, or eyes. They were often employed to check out what was going on in rival kingdoms. The following is an Akkadian text from one "brother" king to another, complaining he had released the scouts according to a deal that was made but had not been paid the ransom as promised: "To Til-abnu: thus says Jakun-Asar your "brother? previously about the scout's release you wrote to me. As for the scouts which came in my power I have released. That I have indeed released (them) you know, still you have not sent the money for ransom. Every since I began releasing your scouts, you have consistently not provided the money for ransom. I here — and you there’should (both) release!"

Sumerian Economics

Transfer of cattle from Ur Organized production of handcrafted good was first developed in Mesopotamia. The Sumerians produced manufactured goods. The weaving of wool by thousands of workers is regarded as the for large-scale industry.

The Sumerians a developed sense of ownership and private property. It seems like many business transactions were recorded and the minutest amounts and smallest quantities were listed. Contracts were sealed with cylinder seals that were rolled over clay to produce a relief image. There wasn't much in Ur and other cities in Mesopotamia except water from the Euphrates River and mud brick made from the dry earth. Prized materials such as gold, silver, lapis lazuli, agate, carnelian all were imported.

The Sumerians established trade links with cultures in Anatolia, Syria, Persia and the Indus Valley. Similarities between pottery in Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley indicate that trade probably occurred between the two regions. During the reign of the pharaoh Pepi I (2332 to 2283 B.C.) Egypt traded with Mesopotamian cities as far north as Ebla in Syria near the border of present-day Turkey.

The Sumerians traded for gold and silver from Indus Valley, Egypt, Nubia and Turkey; ivory from Africa and the Indus Valley; agate, carnelian, wood from Iran; obsidian and copper from Turkey; diorite, silver and copper from Oman and coast of Arabian Sea; carved beads from the Indus valley; translucent stone from Oran and Turkmenistan; seashell from the Gulf of Oman. Raw blocks of lapis lazuli are thought to have been brought from Afghanistan by donkey and on foot. Tin may have come from as far away as Malaysia but most likely came from Turkey or Europe.

Irrigation in Mesopotamia

Mesopotamians developed irrigation agriculture. To irrigate the land, the earliest inhabitants of the region drained the swampy lands and built canals through the dry areas. This had been done in other places before Mesopotamian times. What made Mesopotamia the home of the first irrigation culture is that the irrigation system was built according to a plan, and an organized work force was required to keep the system maintained. Irrigation system began on a small-scale basis and developed into a large scale operation as the government gained more power.

The Sumerians initiated a large scale irrigation program. They built huge embankments along the Euphrates River, drained the marshes and dug irrigation ditches and canals. It not only took great amount of organized labor to build the system it also required a great amount of labor to keep it maintained. Government and laws were created distribute water to make sure the operation ran smoothly.

Archaeologists have found 3,300-year-old plow furrows with water jars still lying by small feeder canals near Ur in southern Iraq.

Ur and Abraham

Adam and Eve cylinder seal Biblical Abraham was born under the name Abram in the Sumer city of Ur in Mesopotamia (in present day Iraq). According to Genesis, Abraham was the great, great, great, great, great, great, great, great grandson of Noah and was married to Sarah.Genesis 11:17-28, reads “Terah Begot Abram, Nahor, and Haran, and Haran begot Lot. And Haran died in the lifetime of Terah his Father in the land of his birth, Ur of Chaldees.”

According to Genesis Abraham, his father, Sara and his orphaned nephew Lot moved from Ur to Haran, 600 miles away in present-day Turkey. The journey probably took months. The Bible offers no explanation why Abraham left Ur. Sarah was originally names Sarai. She received her name Sarah from God.

The Koran and Jewish tradition suggest the following reason for Abraham’s departure from Ur: King Nimrod of Ur (or Babylon) tried to have young Abraham burned alive for refusing to worship local gods. Divine forces intervened to protect him. According to a Jewish story King Nimrod was told a prophet that a man would rise up against him and his pagan religion and Nimrod believed that Abraham might be this man and forced him to flee.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except irrigation picture from Michigan State University

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018