Home | Category: Muhammad and the Arab Conquest / Arab Conquest After Muhammad / Arab Conquest After Muhammad

HOW DID THE ARAB CONQUEST OCCUR?

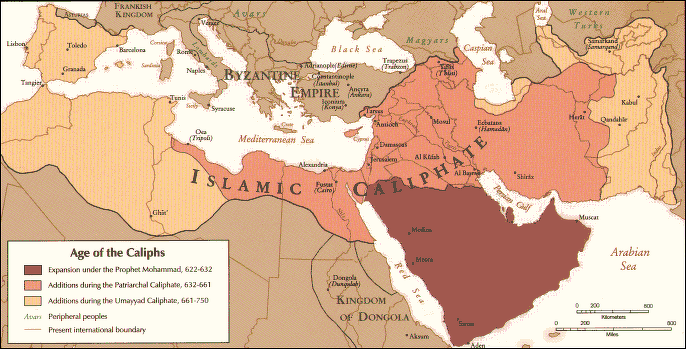

Arab conquest and expansion under Muhammad and the Rashidun Empire At the time of Muhammad's death in A.D. 632, Islam was primarily a local phenomena. But by 634, it had spread throughout Arabia. Muslim armies confronted the Byzantine Empire and seized the province of Palestine, where Jerusalem was located. They also seized Syria, Persia (Iran), and much of Egypt. In 638 the second caliph, or successor to Muhammad, Umar, accepted the surrender of the city of Jerusalem from the Byzantines. The first wave of conquests by Muslim Arabs, completed at the beginning of the eighth century A.D., included the Fertile Crescent, Iran, Egypt, North Africa, Spain, the western fringes of India, and some parts of Central Asia.

How did this huge and sudden expansion occur? While Christianity was spread around the world by missionaries, Islam was mainly spread by conquering armies. This was the case not because of something particularly vicious or warlike about the Arabs or Muslims but rather because the areas the Arabs invaded were either weak or sparsely populated.

Early Islamic polity was intensely expansionist, fueled both by fervor for the faith and by economic and social factors. After gaining control of Arabia and the Persian Gulf region, conquering armies swept out of the peninsula, spreading Islam. By the end of the eighth century, Islamic armies had reached far into North Africa and eastward and northward into Asia. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, Persian Gulf States: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1993 *]

Hugh Kennedy wrote in ““There are many accounts from the period about the early Muslim conquests, but much of the material is unreliable and written to present things in a way that glorified the victors and their God... As explanations for the great events of the seventh century these are at best partial. This is not to say that the Muslims were not brave and that the conviction that they were doing Allah's will was not significant: it clearly was. But their opponents also had firm ideological commitments and there is no reason to assume that individuals were likely to be any less brave. Despite the great mass of words, the full explanation for Muslim victory still eludes us.” [Source: Hugh Kennedy, “The Armies of the Caliphs: Military and Society in the Early Islamic State, 2001]

See Separate Articles: ARAB-MUSLIM CONQUESTS (A.D. 632-700) africame.factsanddetails.com ; ARAB TRIBALISM AND THE ARAB-MUSLIM CONQUESTS (632-700) africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Islamic History: History of Islam: An encyclopedia of Islamic history historyofislam.com ; Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World oxfordislamicstudies.com ; Sacred Footsetps sacredfootsteps.com ; Islamic History Resources uga.edu/islam/history ; Internet Islamic History Sourcebook fordham.edu/halsall/islam/islamsbook ; Islamic History friesian.com/islam ; Muslim Heritage muslimheritage.com ; Chronological history of Islam barkati.net

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In”

by Hugh Kennedy Amazon.com ;

“In God's Path: The Arab Conquests and the Creation of an Islamic Empire” by Robert G. Hoyland, Peter Ganim, et al. Amazon.com ;

“In the Shadow of the Sword: The Birth of Islam and the Rise of the Global Arab Empire

by Tom Holland, Steven Crossley, et al. Amazon.com ;

“After the Prophet: The Epic Story of the Shia-Sunni Split in Islam” by Lesley Hazleton and Blackstone Amazon.com ;

“The Arabs: A History” by Eugene Rogan Amazon.com ;

“The New Cambridge History of Islam: Volume 1, Formation of the Islamic World, 6th to 11th Centuries Amazon.com ;

“Arabs: A 3,000-Year History of Peoples, Tribes, and Empires” by Tim Mackintosh-Smith, Ralph Lister, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Arabs in History” by Bernard Lewis Amazon.com ;

“History of Islam” (3 Volumes) by Akbar Shah Najeebabadi and Abdul Rahman Abdullah Amazon.com ;

“Islam, a Short History “ by Karen Armstrong Amazon.com ;

“A History of the Muslim World: From Its Origins to the Dawn of Modernity”

by Michael A. Cook, Ric Jerrom, et al. Amazon.com ;

”History of the Arab People” by Albert Hourani (1991) Amazon.com ;

“Islam Explained: A Short Introduction to History, Teachings, and Culture” by Ahmad Rashid Salim Amazon.com ;

“No God but God” by Reza Aslan Amazon.com ;

“Muhammad: A Prophet for Our Time” by Karen Armstrong Amazon.com ;

“The Messenger: The Meanings of the Life of Muhammad” by Tarqi Ramadan Amazon.com

Arab World After Muhammad’s Death

Rashidun Caliphate: Muhammad (top, velied) and the first four Caliphs, Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman and Ali

After the death of Muhammad, his four immediate successors, remembered in Sunni Islam as the Rightly Guided Caliphs (reigned 632–61), oversaw the consolidation of Muslim rule in Arabia and the broader Middle East (Egypt, Palestine, Iraq, and Syria), overrunning the Byzantine and Sasanid empires. A period of great central empires was followed with the establishment of the Umayyad (661–750) and then the Abbasid (750–1258) empires. Within a hundred years of the death of Muhammad, Muslim rule extended from North Africa to South Asia, an empire greater than Rome at its zenith.

At the time of his death Muhammad enjoyed the loyalty of almost all of Arabia. The peninsula's tribes had tied themselves to the Prophet with various treaties but had not necessarily become Muslim. The Prophet expected others, particularly pagans, to submit but allowed Christians and Jews to keep their faith provided they paid a special tax as penalty for not submitting to Islam. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Saudi Arabia: A Country Study, U.S. Library of Congress, 1992 *]

By A.D. 632, Muhammad and his followers had brought most of the tribes and towns of the Arabian Peninsula under the banner of the new monotheistic religion of Islam (literally, "submission"), which was conceived of as uniting the individual believer and society under the omnipotent will of Allah (God). Islamic rulers therefore exercised both temporal and religious authority. Adherents of Islam, called Muslims ("those who submit" to the will of God), collectively formed the House of Islam (Dar al Islam). Within a generation, Arab armies had carried Islam north and east from Arabia and westward into North Africa. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Libya: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1987*]

For the first 30 years following the Prophet’s death, caliphs ruled the Islamic world from Yathrib, today known as Medina. Responding to threats from the Byzantine and Persian empires, the caliphs demanded allegiance from the Arab tribes. In a relatively short span of time, the Islamic empire expanded northward into present-day Spain, Pakistan, and the Middle East. However, maintaining unity proved to be a continual challenge. Following the death of the third caliph, Uthman, in 656, splits appeared in the burgeoning Islamic empire. The Umayyads (661–750) established a hereditary line of caliphs centered in Damascus. The Abbasids, claiming a different hereditary line, overthrew the Umayyads in 750 and moved the caliphate to Baghdad. Although the spiritual significance of Mecca and Medina remained constant, the political importance of Arabia in the Islamic world waned. [Source: Library of Congress, September 2006 **]

Reasons for the Arab Conquest

Fred Donner of the University of Chicago wrote: “Most difficult of all to explain is what caused the conquest itself -- that is, what it was that led the ruling elite of the new Islamic state to embrace an expansionist policy. Several factors can plausibly be suggested, however, any or all of which probably led specific individuals in the elite to think in terms of an expansionist movement. First, there is the possibility that the ideological message of Islam itself filled some or all of the ruling elite with the notion that they had an essentially religious duty to expand the political domain of the Islamic state as far as practically possible; that is, the elite may have organized the Islamic conquest movement because they saw it as their divinely ordained mission to do so. This view coincides closely with the traditional view adopted by Muslims themselves. Skeptical modern scholars have tended to discount the religious factor, but it must be borne in mind that as an ideological system early Islam came with great force onto the stage of Arabian society -- we have seen how it appears to have laid the groundwork for a radical social and political transformation of that society. [Source: Fred Donner, “The Early Islamic Conquests,” Princeton University Press, 1981, beginning with pg. 251. Donner is a scholar of Islam and Professor of Near Eastern History at the University of Chicago =]

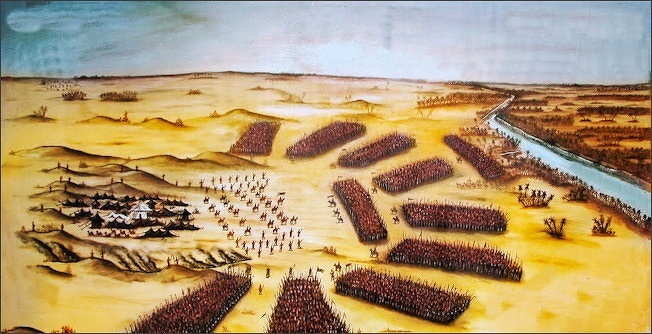

battle between Arabs and Persians

“The pristine vigor of early Islam may be difficult to sense now, after the passage of so many centuries and in the context of an age dominated by social and political ideas very different from those of ancient Arabia, but its revolutionary impact on seventh-century Arabia can hardly be doubted. We should, therefore, be wary of recent attempts simply to dismiss as insignificant what was clearly felt by contemporaries to be a profoundly powerful movement. Furthermore, we must recognize that even in cases where other, more mundane factors were partly responsible for stirring an individual member of the elite to favor the idea of an expansionist movement, it was Islam that provided the ideological sanction for such a conviction. The precise degree to which the purely ideological element may have bolstered the practical resolve of the elite to embark on an expansion that was considered worthwhile for other reasons as well can hardly be estimated, but it would be unrealistic, indeed foolhardy, to dismiss ideology or faith as a factor altogether. Some of the ruling elite, then, may well have believed in expansion of the state and the conquest of new areas simply because they saw it as God's will, and many others were surely susceptible to the psychological comfort of having such legitimation for their actions. =

“Other factors, however, certainly contributed to the adoption of an expansionist policy by the state. Much of the elite -- the Quraysh, Thaqlf, and many Medinese as well -- may have wanted to expand the political boundaries of the new state in order to secure even more fully than before the trans-Arabian commerce they had plied for a century or more, or to recapture routes that had shifted north. There is ample evidence that members of the ruling elite retained a lively interest in commerce during the conquest period and wished to use wealth and influence accruing to them as governors or generals for new commercial ventures; 'Utba b. Abl Sufyan, for example, who was 'Umar's tax agent over the Kinana tribe, wanted to use the money he made from the post for trade. The Quraysh in particular, perhaps because of their long-standing commercial contacts in Syria, may have been especially eager to see the state expand in that direction. There were also other financial advantages that would accrue to the elite from the expansion of the statc: the acquisition of properties in the conquered areas, the ability of the state to levy taxes on conquered populations, the booty in wealth and slaves, at least some of which would reach the ruling elite even if they did not participate actively in the campaigns that seized them. =

“Finally, there is the possibility that members of the elite saw an expansion of the state as necessary in order to preserve their hard-won position at the top of the new political hierarchy. The policy of encouraging tribesmen to emigrate, upon which the continued dominance of the elite in part rested, was itself dependent on the successful conquest of new domains in which the emigrant tribesmcn could bc lodged. This view suggests that the conquest of Syria and Iraq was one of the objectives of the ruling elite from a fairly early date. On thc other hand, it is also possible to argue that the conquest of Syria and Iraq were merely side effects of the state's drive to consolidate its power over all Arab tribes, including those living in the Syrian desert and on the fringes of Iraq. This process generated the direct clashes with the Byzantine and Sasanian Empires that ultimately led to the Islamic conquest of Syria and Iraq, but that does not neccessarily imply that the conquest of Syria and Iraq was a conscious objective of the ruling elite from the start. =

“These considerations can serve as plausible guesses as to why the state and its dominant elite adopted an expansionist policy. In the absence of real primary sources that might illuminate for us the actual motivations of individuals and of the elite as a body, they will have to remain merely guesses. The true causes of the Islamic conquests — currents in the minds of men — will probably remain forever beyond the grasp of historical analysis.

Unifying the Arab Tribes and Areas After Muhammad

Muhammad forever shaped Arabia. Today, many Arabs refer to the era before the introduction and spread of Islam as “the time of ignorance.” Muhammad was born in the city of Mecca into the prominent Quraysh tribe. His life and ministry did much to unify Arabia. Until the seventh century, the peninsula’s tribes fought a destructive series of wars for control of the region. The situation had changed dramatically by the time of Muhammad’s death in A.D. 632. Muhammad, as well as his political successor Abu Bakr, enjoyed the loyalty of almost all of Arabia. Although the Prophet did not appoint a spiritual successor, the institution of the caliphate emerged and expanded the Islamic empire. [Source: Library of Congress, September 2006 **]

Traditional accounts of the conversion of tribes in the gulf are probably more legend than history. Stories about the Bani Abd al Qais tribe that controlled the eastern coast of Arabia as well as Bahrain when the tribe converted to Islam indicate that its members were traders having close contacts with Christian communities in Mesopotamia. Such contacts may have introduced the tribe to the ideal of one God and so prepared it to accept the Prophet's message. The Arabs of Oman also figure prominently among the early converts to Islam. According to tradition, the Prophet sent one of his military leaders to Oman to convert not only the Arab inhabitants, some of whom were Christian, but also the Persian garrison, which was Zoroastrian. The Arabs accepted Islam, but the Persians did not. It was partly the zeal of the newly converted Arabs that inspired them to expel the Persians from Oman. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, Persian Gulf States: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1993 *]

tribes of pre-Islamic Arabia

Fred Donner,a scholar of Islam and Professor of Near Eastern History at the University of Chicago, wrote: “The appearance of the unifying ideology of Islam, coupled with the skillful use of both traditional and novel means of political consolidation, resulted in the emergence under Muhammad and Abu Bakr of a new state that was able to organize and dominate more effectively than ever before the different tribal groups of the Arabian peninsula. In place of the extreme political fragmentation that had formerly existed in Arabia, with various tribal groups vying with one another for local dominance, there emerged a relatively centralized, unified, and unifying polity that integrated most of these tribes into istelf and made them functioning parts of the larger whole. [Source: Fred Donner, “The Early Islamic Conquests,” Princeton University Press, 1981, beginning with pg. 251. Donner is a scholar of Islam and Professor of Near Eastern History at the University of Chicago =]

“It was this integration of the Arabian tribes into a single new Islamic state that set the stage for the conquests, which in fact represented the fruit of that integration. The process of state consolidation that began with Muhammad continued unabated throughout the whole period of the early Islamic conquests. As under Muhammad, each tribal group integrated into the state during the conquest period was administered by an agent (amil), often one of the Quraysh or the ansar, who appears to have supervised the tribe and collected the taxes that weer due from it. There were, as we have seen, such governors or agents over some of the tribes of Quda'a in southern Syria under Abu Bakr, and we read that somewhat later, under Uthman, a member of the Quraysh named al-Hakam b. Abi l-'As was appointed to collect taxes from the Quda'a. Likewise, Sa'd b. Abi Waqqas had served as Umar's agent in charge of collecting the sadaqa tax from the Hawazin tribe in the Najd before being appinted commander of the army that marched to al-Qadisiyya; Utba b. Abi Sufyan was Umar's agent among the Kinana tribe; and the existence of the agents over other tribes in Arabia in Umar's day is well attested by numerous references. =

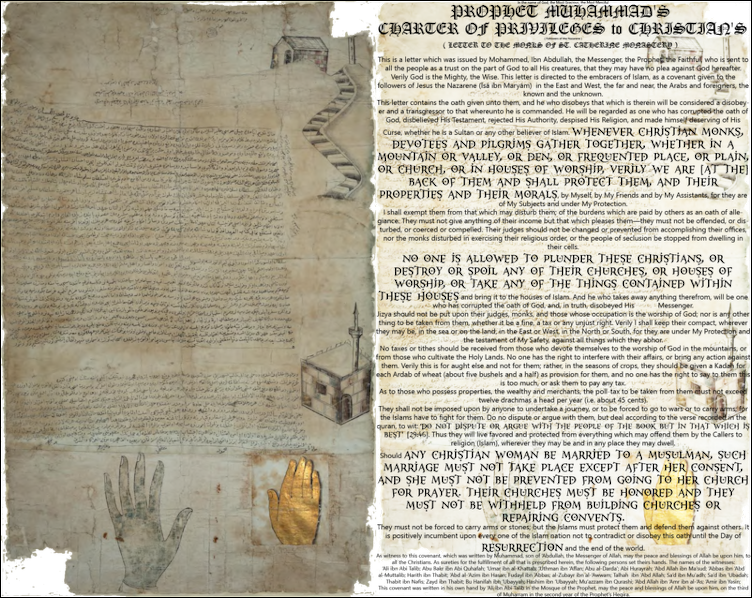

Although Muhammad had enjoined the Muslim community to convert the infidel, he had also recognized the special status of the "people of the book," Jews and Christians, whose scriptures he considered revelations of God's word and which contributed in some measure to Islam. By accepting the status of dhimmis (tolerated subject people), Jews and Christians could live in their own communities, practice their own religious laws, and be exempt from military service. However, they were obliged to refrain from proselytizing among Muslims, to recognize Muslim authority, and to pay additional taxes. In addition, they were denied certain political rights.*

See Separate Article ARAB TRIBALISM AND THE ARAB CONQUEST (632-700) factsanddetails.com

Jihad

The concept of Jihad was used to spread of Islam. Because Muslims aren’t supposed to fight other Muslims,” jihad" was directed at those who had not accepted the will of god. Jihad means "struggle" or "striving" not "holy war" and comes from the Qur’anic phrase Jihad fi sabeel Allah (“striving in the path of God”). It refers to the obligation of individual Muslims and Muslim societies to strive for self-improvement and self-purification. Muhammad said that jahad bil nafs (“striving within the self”) is the "greatest jihad." It is based in the Qur’anic saying (9:125): “O you who believe, fight the unbelievers who are near to you."

Muhammad receiving the submission of Banu Nadir

Jihad fi sabeel Allah refers the "unremitting war" against evil, corruption, injustice, tyranny and oppression. It refers to a struggle in all aspects of life, from learning in school to fighting a holy war for justice. This can take the form of writing articles, publishing books or speaking out against those who ignore Islamic principals. Force is to be used only as a last resort.

Jihad is regarded as a duty of all Muslims: an obligation not a choice. Because Muslims aren't supposed to fight other Muslims, jihad is sometimes directed at infidels, or those who have not accepted the will of god. Some extremists — both Muslim and non-Muslim ones — see the world as being shaped by a kind of perpetual war between Muslims and non-Muslims (infidels), with jihad defining the conflict until the whole world embraces Islam. One Taliban fighter said, “Jihad is like a cancer. Nobody can cure it, nobody can help you."

Jihad has been interpreted in different ways at different times. Some of the basic principals were formed during Muhammad's lifetime, when his community fought for survival in a hostile environment, and the early decades after Muhammad's death, when a policy of expansion was declared that tapped into the warring tendencies of Arab tribesmen. This period also coincided with period in which sharia (Muslim law) was shaped and one of the consequences of this was to give jihad legal claims. David Van Beima wrote in Time, “the bellicosity of some Qur’anic passages owes much to the fact that were written at a time when Muslims were engaged in almost constant warfare to defend their religion."

Dilip Hiro wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “An Arabic word, "jihad" has a broad range of meaning. It can refer to an individual Muslim's internal struggle to adhere more faithfully to the teachings of Islam or, at the other extreme, to a holy war waged against external forces threatening Islam. In modern times, jihad has most often meant using violence against the regimes of Muslim leaders considered un-Islamic; and it has been waged with the goal of establishing a state administered according to sharia law. The jihadist agenda until quite recently was usually local. This changed after the Soviet Union intervened in Afghanistan in 1979. Pakistani-based leaders of an anti-Soviet jihad in Afghanistan invited militant Muslims from around the world to join their campaign. At that point, with support from the United States, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, jihadism went global. [Source: Dilip Hiro, Los Angeles Times, May 29, 2012]

See Separate Article JIHAD factsanddetails.com

Arab Warfare

Arab soldiers were of relatively poor quality and, although experienced raiders, they had never fought in large armies before. If this was the case, why were they so successful? The reason they were successful as conquerors, many have argued, was their religious zeal. Their belief that they would go to heaven if they died in war, made them fearless and formidable warriors even when matched against more disciplined armies that outnumbered them. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

Bedouin raod

Many soldiers believed that God predestined them to victory and they were willing to return to the battlefield again and again. Some soldiers wore chain mail in which every steel link was stamped with the name of Allah, Muhammad or Islamic saints, or carried "saddle Qur’ans, which consisted of nested boxes to protect the Qur’an from desert sands. On the battlefield Arab chose positions easily defended with obstacles for defense. They preferred places with a good escape route. Supplies were moved effectively on camels,

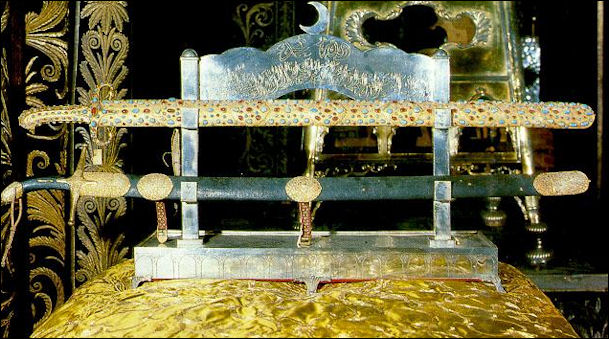

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The weapon most readily associated by today's audiences with Muslim warriors of bygone times is probably the scimitar or saber, having a long, slightly curved blade with a single cutting edge. Other arms included javelins (throwing spears), battle axes, maces, and recurve bows (so called because the ends of the arms/limbs in their relaxed state curve forward, adding additional momentum to the arrow when the bow is strung). Although the above weapons were certainly also used by foot soldiers, all were essentially suited for use by cavalry. [Source: Department of Arms and Armor, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“Sword blades of "Damascus steel" or "watered steel" refer to blades that had been given a wavy or "watered" pattern, produced in the steel prior to forging using specific smelting and crucible techniques. Although this technique was practiced in the Islamic Middle East at least since the Middle Ages, in western Europe such blades were believed to originate from Damascus (Syria), hence the name. Along similar lines, the inlay of metal surfaces such as those of a breastplate or a sword blade with gold or silver was known as "damascening," a term again alluding to the city of Damascus and the apparent Eastern origins of this technique.”\^/

Islamic Armor

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “One of the main characteristics of Islamic armor is that, compared to its European counterparts, it is often relatively lighter and less extensive. This fact owes as much to a strategic and tactical preference of most Muslim armies for speed over heavy protection, as to the usually hot climate of regions under Islamic rule. An example is the extensive and continued use of mail armor until well into the nineteenth century, while in western Europe this type of defense had been largely relegated to a secondary position with the development of plate armor at the beginning of the fifteenth century. In Islamic armor, the use of plate was usually confined to helmet, short vambraces (arm defenses) and greaves (lower leg defenses), and, to some extent, reinforcement of the mail shirt. [Source: Department of Arms and Armor, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

Muhammad Swords

“Apart from shirts made entirely of mail, one of the most typically "Islamic" forms of body defense is a shirt composed of steel plates joined by areas of mail, which appears to have been developed first in Iran or Anatolia during the early fifteenth century. Variations with plates of different sizes and configurations were being worn in many parts of the Ottoman empire by the sixteenth century, whence it was probably introduced into India early in the Mughal period due to the Ottoman influence on Mughal military practices.\^/

“The most familiar characteristic of Islamic armor is perhaps the distinctive conical-shape helmets, which, with some variation, are found in most European and Near Eastern areas under Islamic rule. One variation is known as a "turban helmet." Its prototype can be found in the pre-Islamic Sasanian tradition (224–336) of Persia, but its sweeping outline, reminiscent of the domes of mosques, has contributed to this type of helmet being recognized today as decidedly Islamic. Many of the early surviving examples date from the fifteenth century and seem to have been made in Iran and Turkey. Additional protection was afforded by shields, usually of round shape, and constructed—unlike the majority of their European counterparts—of metal.\^/

Conversion by Conquest?

George F. Nafziger and Mark W. Walton wrote in “Islam at War”: According to the BBC: “The early advance of Islam went hand in hand with military expansion - whether it was the motivation for it is difficult to tell, although one recent book suggests that Islam certainly facilitated the growth of Muslim power. ...only one possible explanation remains for the Arab success-and that was the spirit of Islam... The generous terms that the invading armies usually offered made their faith accessible to the conquered populations. And if it was a new and upstart faith, its administration by simple and honest men was preferable to the corruption and persecution that were the norm in more civilized empires. [Source: George F. Nafziger, Mark W. Walton, “Islam at War: A History,” 2003 ==]

“And Islam benefited greatly from the astonishing military success of the armies of Arabia... the real victor in the conquests was not the Arab warlords, but Islam itself... Simply put, Islam may have sped the conquests, but it also showed much greater staying power. It is useful to realize that the power of Islam was separate from much and more permanent than that of the armies with which it rode.” ==

Jonathan P. Berkey wrote in “The Formation of Islam: Religion and Society in the Near East,” But the Arab military adventures do not seem to have been intended as a religious war of conversion. In the wake of the Ridda wars, and of the Arabs' sudden conquest of most of the Near East, the new religion became identified more sharply as a monotheism for the Arab people. As is well known, the Arabs made no attempt to impose their faith on their new subjects, and at first in fact discouraged conversions on the part of non-Arabs. [Source: Jonathan P. Berkey, “The Formation of Islam: Religion and Society in the Near East, 600-1800,” 2003]

Covenant of the Prophet Muhammad (Charter of Privelages translation)

Justification of Conquest

According to the BBC: “Whether or not Islam provided the motivation for early Muslim imperialism, it could be used to provide justification for it - in the same way that it had previously been used to support Muhammad's own actions against his opponents. [Source: BBC, September 3, 2009 |::|]

“The Qur'an has a number of passages that support military action against non-Muslims, for example: “But when the forbidden months are past, then fight and slay the Pagans wherever ye find them, and seize them, beleaguer them, and lie in wait for them in every stratagem (of war) (from Qur'an 9:5). “Fight those who believe not in Allah nor the Last Day, nor hold that forbidden which hath been forbidden by Allah and His Messenger, nor acknowledge the religion of Truth, (even if they are) of the People of the Book (from Qur'an 9:29).

“Other passages confirmed the rightness of the ancient military tradition of looting from the defeated, and specified how the booty should be divided. |This is not surprising, as the armies of those days were not like modern armies - but more like a federation of tribal mercenary groups who were not paid and whose only material reward came from the spoils of war.

Jonathan P. Berkey wrote in “The Formation of Islam: Religion and Society in the Near East”: “The political status of Islam, and the role Muhammad had given it as a political as well as a religious force, was reinforced in the military conquests. A caliph such as Umar seems to have regarded himself, first and foremost, as the leader of the Arabs, and their monotheistic creed as the religious component of their new political identity. [Source: Jonathan P. Berkey, “The Formation of Islam: Religion and Society in the Near East, 600-1800,” 2003]

Rise of the Islamic War Machine

Bernard Lewis wrote in The New Yorker: “In the course of human history, many civilizations have risen and fallen—China, India, Greece, Rome, and, before them, the ancient civilizations of the Middle East. During the centuries that in European history are called medieval, the most advanced civilization in the world was undoubtedly that of Islam. Islam may have been equalled—or even, in some ways, surpassed—by India and China, but both of those civilizations remained essentially limited to one region and to one ethnic group, and their impact on the rest of the world was correspondingly restricted. The civilization of Islam, on the other hand, was ecumenical in its outlook, and explicitly so in its aspirations. One of the basic tasks bequeathed to Muslims by the Prophet was jihad. This word, which literally means “striving,” was usually cited in the Qur’anic phrase “striving in the path of God” and was interpreted to mean armed struggle for the defense or advancement of Muslim power. In principle, the world was divided into two houses: the House of Islam, in which a Muslim government ruled and Muslim law prevailed, and the House of War, the rest of the world, still inhabited and, more important, ruled by infidels. Between the two, there was to be a perpetual state of war until the entire world either embraced Islam or submitted to the rule of the Muslim state. [Source: Bernard Lewis, The New Yorker, November 19, 2001 ]

Battle of Karbala

“From an early date, Muslims knew that there were certain differences among the peoples of the House of War. Most of them were simply polytheists and idolaters, who represented no serious threat to Islam and were likely prospects for conversion. The major exception was the Christians, whom Muslims recognized as having a religion of the same kind as their own, and therefore as their primary rival in the struggle for world domination—or, as they would have put it, world enlightenment. It is surely significant that the Qur’anic and other inscriptions on the Dome of the Rock, one of the earliest Muslim religious structures outside Arabia, built in Jerusalem between 691 and 692 A.D., include a number of directly anti-Christian polemics: “Praise be to God, who begets no son, and has no partner,” and “He is God, one, eternal. He does not beget, nor is he begotten, and he has no peer.” For the early Muslims, the leader of Christendom, the Christian equivalent of the Muslim caliph, was the Byzantine emperor in Constantinople. Later, his place was taken by the Holy Roman Emperor in Vienna, and his in turn by the new rulers of the West. Each of these, in his time, was the principal adversary of the jihad.

“In practice, of course, the application of jihad wasn’t always rigorous or violent. The canonically obligatory state of war could be interrupted by what were legally defined as “truces,” but these differed little from the so-called peace treaties the warring European powers signed with one another. Such truces were made by the Prophet with his pagan enemies, and they became the basis of what one might call Islamic international law. In the lands under Muslim rule, Islamic law required that Jews and Christians be allowed to practice their religions and run their own affairs, subject to certain disabilities, the most important being a poll tax that they were required to pay. In modern parlance, Jews and Christians in the classical Islamic state were what we would call second-class citizens, but second-class citizenship, established by law and the Qur’an and recognized by public opinion, was far better than the total lack of citizenship that was the fate of non-Christians and even of some deviant Christians in the West. The jihad also did not prevent Muslim governments from occasionally seeking Christian allies against Muslim rivals—even during The Crusades, when Christians set up four principalities in the Syro-Palestinian area. The great twelfth-century Muslim leader Saladin, for instance, entered into an agreement with the Crusader king of Jerusalem, to keep the peace for their mutual convenience.

“Under the medieval caliphate, and again under the Persian and Turkish dynasties, the empire of Islam was the richest, most powerful, most creative, most enlightened region in the world, and for most of the Middle Ages Christendom was on the defensive. In the fifteenth century, the Christian counterattack expanded. The Tatars were expelled from Russia, and the Moors from Spain. But in southeastern Europe, where the Ottoman sultan confronted first the Byzantine and then the Holy Roman Emperor, Muslim power prevailed, and these setbacks were seen as minor and peripheral. As late as the seventeenth century, Turkish pashas still ruled in Budapest and Belgrade, Turkish armies were besieging Vienna, and Barbary corsairs were raiding lands as distant as the British Isles and, on one occasion, in 1627, even Iceland.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, Al Jazeera, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Library of Congress and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024