Home | Category: Early Mesopotamia, the Fertile Crescent and Archaeology

MESOPOTAMIA

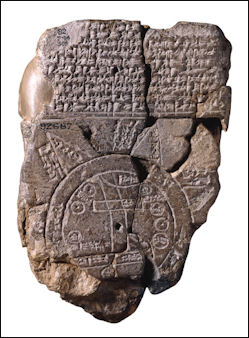

Baylonian maps Strategically situated in the heart of the Near East and northeastern part of the Middle East, Mesopotamia was located south of Persia (Iran) and Anatolia (Turkey), east of ancient Egypt and the Levant (Lebanon, Israel, Jordan and Syria) and east of the Persian Gulf. Almost completely landlocked, its only outlet to sea is the Fao peninsula, a small chunk of land wedged between modern-day Iran and Kuwait, which opens to the Persian Gulf, which in turn opens into the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean.

Nancy Demand of Indiana University wrote: “The name Mesopotamia (meaning "the land between the rivers") refers to the geographic region which lies near the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers and not to any particular civilization. In fact, over the course of several millennia, many civilizations developed, collapsed, and were replaced in this fertile region. The land of Mesopotamia is made fertile by the irregular and often violent flooding of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. While these floods aided agricultural endeavors by adding rich silt to the soil every year, it took a tremendous amount of human labor to successfully irrigate the land and to protect the young plants from the surging flood waters. Given the combination of fertile soil and the need for organized human labor, perhaps it is not surprising that the first civilization developed in Mesopotamia.” [Source: The Asclepion, Prof.Nancy Demand, Indiana University - Bloomington]

Much of the agricultural land is in the fertile valleys and plains between the Tigris and Euphrates and their tributaries. Much of the agricultural land was irrigated. The forest are found predominantly in the mountains. Occupied by desert and alluvial plains, modern Iraq is the only country in the Middle East that has good supplies of water and oil. Most of the water comes Tigris and Euphrates. He main oil fields are near 1) Basra and the Kuwait border; and 2) near Kirkuk in northern Iraq. The majority of Iraqis live in cities in the fertile Tigris and Euphrates River valley between the Kuwait border and Baghdad.

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Cultural Atlas of Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East” by Michael Roaf (1990) Amazon.com;

“Mountains and Lowlands: Ancient Iran and Mesopotamia” by Paul Collins (2016) Amazon.com;

“Climate Change in the Middle East and North Africa: 15,000 Years of Crises, Setbacks, and Adaptation” by William R. Thompson and Leila Zakhirova (2021) Amazon.com;

“Climate, Environment and Agriculture in Assyria: In the 2nd Half of the 2nd Millennium BCE” (Studia Chaburensia) by Herve Reculeau (2011) Amazon.com;

“Challenging Climate Change: Competition and Co-operation Among Pastoralists and Agriculturalists in Northern Mesopotamia (c.3000-1600 BC)” (2009) by Arne Wossink Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamia: an Enthralling Overview of Mesopotamian History (2022) Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamia: a Captivating Guide (2019) Amazon.com;

“Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization” by Paul Kriwaczek (2010) Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamia:Civilization Begins” by Ariane Thomas and Timothy Potts (2020) Amazon.com;

“Mesopotamia: The Invention of the City“ by Gwendolyn Leick (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Legacy of Mesopotamia” by Stephanie Dalley, A. T. Reyes, et al. (2006) Amazon.com;

“Civilizations of Ancient Iraq” by Benjamin R. Foster and Karen Polinger Foster ((2009) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Iraq” by Georges Roux (1964) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamia” by Don Nardo (2004) Amazon.com;

“DK Eyewitness Books: Mesopotamia: Discover the Cradle of Civilization—the Birthplace of Writing, Religion, and the” by John Farndon and Philip Steele (2007) Amazon.com;

“Between Two Rivers: Ancient Mesopotamia and the Birth of History” by Moudhy Al-Rashid (2025) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Near East” Volume One by James B. Pritchard (1965) Amazon.com;

“A History of the Ancient Near East” by Marc Van De Mieroop (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization” by Adolf Leo Oppenheim (1964) Amazon.com;

Regions of Iraq and Mesopotamia

Modern Iraq is divided into four principal regions: 1) an upper plain between the Tigris and Euphrates which stretches from north and west of Baghdad to the Turkish border and is regarded as the most fertile part of the country; 2) the lower plain between the Tigris and Euphrates, which extends from north and west of Baghdad to Persian Gulf and embraces a large area of marshes, swamps and narrow waterways; 3) mountains in the north and northeast along the Turkish and Iranian borders; 4) and vast deserts which spread south and west of the Euphrates to the borders of Syria, Jordan and Saudi Arabia.

Modern Iraq is divided into four principal regions: 1) an upper plain between the Tigris and Euphrates which stretches from north and west of Baghdad to the Turkish border and is regarded as the most fertile part of the country; 2) the lower plain between the Tigris and Euphrates, which extends from north and west of Baghdad to Persian Gulf and embraces a large area of marshes, swamps and narrow waterways; 3) mountains in the north and northeast along the Turkish and Iranian borders; 4) and vast deserts which spread south and west of the Euphrates to the borders of Syria, Jordan and Saudi Arabia.

Deserts, semideserts and steppes cover about two thirds of modern Iraq. The southwestern and southern third of Iraq is covered by barren desert with virtually no plant life whatsoever. This region is occupied mostly by the Syrian and Arabian Deserts and has a only few oases. The semi deserts are not as dry as the deserts. These resemble the deserts of southern California. Plant life includes tamarisk shrubs, and biblical plants like of apple-of-Sodom and Christ-thorn tree.

Iraq’s mountains are found primarily in the north and northeast along the borders of Turkey and Iran and to a lesser extent Syria. The Zagros mountains run along the Iranian border. Many of the mountains in Iraq are treeless but many have highlands and valleys with grass that has traditionally been utilized by nomadic herders and their animals. A number of rivers and streams flow out of the mountain. They water narrow green valleys in the foothills of the mountains..

Iraq also has some large lakes. Buhayrat ath Tharthar and Buhayrat ar Razazah are two large lakes about 50 miles from Baghdad. Some have been created modern dams and water projects. In southeast Iraq, along the Tigris and Euphrates and the Iranian border there is a large area of marshes.

Geography of Mesopotamia

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia:“The country lies diagonally from northwest to southeast, between 30° and 33° N. lat., and 44° and 48° E. long., or from the present city of Bagdad to the Persian Gulf, from the slopes of Khuzistan on the east to the Arabian Desert on the west, and is substantially contained between the Rivers Euphrates and Tigris, though, to the west a narrow strip of cultivation on the right bank of the Euphrates must be added. Its total length is some 300 miles, its greatest width about 125 miles; about 23,000 square miles in all, or the size of Holland and Belgium together. Like those two countries, its soil is largely formed by the alluvial deposits of two great rivers. A most remarkable feature of Babylonian geography is that the land to the south encroaches on the sea and that the Persian Gulf recedes at present at the rate of a mile in seventy years, while in the past, though still in historic times, it receded as much as a mile in thirty years. In the early period of Babylonian history the gulf must have extended some hundred and twenty miles further inland. [Source: J.P. Arendzen, transcribed by Rev. Richard Giroux, Catholic Encyclopedia |=|]

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia:“The country lies diagonally from northwest to southeast, between 30° and 33° N. lat., and 44° and 48° E. long., or from the present city of Bagdad to the Persian Gulf, from the slopes of Khuzistan on the east to the Arabian Desert on the west, and is substantially contained between the Rivers Euphrates and Tigris, though, to the west a narrow strip of cultivation on the right bank of the Euphrates must be added. Its total length is some 300 miles, its greatest width about 125 miles; about 23,000 square miles in all, or the size of Holland and Belgium together. Like those two countries, its soil is largely formed by the alluvial deposits of two great rivers. A most remarkable feature of Babylonian geography is that the land to the south encroaches on the sea and that the Persian Gulf recedes at present at the rate of a mile in seventy years, while in the past, though still in historic times, it receded as much as a mile in thirty years. In the early period of Babylonian history the gulf must have extended some hundred and twenty miles further inland. [Source: J.P. Arendzen, transcribed by Rev. Richard Giroux, Catholic Encyclopedia |=|]

“According to historical records both the towns Ur and Eridu were once close to the gulf, from which they are now about a hundred miles distant; and from the reports of Sennacherib's campaign against Bît Yakin we gather that as late as 695 B.C., the four rivers Kerkha, Karun, Euphrates, and Tigris entered the gulf by separate mouths, which proves that the sea even then extended a considerable distance north of where the Euphrates and Tigris now join to form the Shat-el-arab. Geological observations show that a secondary formation of limestone abruptly begins at a line drawn from Hit on the Euphrates to Samarra on the Tigris, i.e. some four hundred miles from their present mouth; this must once have formed the coast line, and all the country south was only gradually gained from the sea by river deposit. In how far man was witness of this gradual formation of the Babylonian soil we cannot determine at present; as far south as Larsa and Lagash man had built cities 4,000 years before Christ. It has been suggested that the story of the Flood may be connected with man's recollection of the waters extending far north of Babylon, or of some great natural event relating to the formation of the soil; but with our present imperfect knowledge it can only be the merest suggestion. It may, however, well be observed that the astounding system of canals which existed in ancient Babylonia even from the remotest historical times, though largely due to man's careful industry and patient toil, was not entirely the work of the spade, but of nature once leading the waters of Euphrates and Tigris in a hundred rivulets to the sea, forming a delta like that of the Nile. |=|

“The fertility of this rich alluvial plain was in ancient times proverbial; it produced a wealth of wheat, barley, sesame, dates, and other fruits and cereals. The cornfields of Babylonia were mostly in the south, where Larsa, Lagash, Erech, and Calneh were the centres of an opulent agricultural population. The palm tree was cultivated with assiduous care and besides furnishing all sorts of food and beverage, was used for a thousand domestic needs. Birds and waterfowls, herds and flocks, and rivers teeming with fish supplied the inhabitants with a rural plenty which surprises the modern reader of the cadastral surveys and tithe-accounts of the ancient temples. The country is completely destitute of mineral wealth, and possesses no stone or metal, although stone was already being imported from the Lebanon and the Ammanus as early as 3000 B.C.; and much earlier, about 4500 B.C., Ur-Nina, King of Shirpurla sent to Magan, i.e. the Sinaitic Peninsula, for hard stone and hard wood; while the copper mines of Sinai were probably being worked by Babylonians shortly after 3750, when Snefru, first king of the Fourth Egyptian dynasty, drove them away. It is remarkable that Babylonia possesses no bronze period, but passed from copper to iron; though in later ages it learnt the use of bronze from Assyria. |=|

Tigris and Euphrates

The Tigris and Euphrates are two of the world’s most famous rivers. The Tigris River is about 1,200 miles (1950 kilometers) long and originates in the mountains of southern Turkey and enters Iraq near the spot where Iraq, Turkey and Syria meet. The Euphrates is about 1,300 miles (2100 kilometers) long and originates in the mountains of central Turkey and flows a considerable distance through Turkey and Syria before it enters western Iraq.

Mesopotamia and the Tigris and Euphrates

The Tigris and Euphrates approach each other near Baghdad and roughly flow parallel to each other, separated by a distance of between 30 and 130 miles (50 to 210 kilometers), before they meet near Basra at Qurna, where they form the Shatt al-Arab, a waterway which flows 120 miles (195 kilometers) into the Persian Gulf and is navigable by large ships.

Silt from the Tigris and Euphrates rivers has built a long, fertile alluvial plain, and a large delta and vast marshes. The area around the rivers has been heavily irrigated since Mesopotamian times. In the north the rivers usually stay within their banks. In the south and east the rivers have traditionally flooded in the spring. Some barriers have been built to prevent this from happening near populated areas.

Snow melt in the mountains in Anatolia in the spring causes the Tigris and Euphrates to rise. The Tigris floods from March to May: the Euphrates, a little later. Some the floods are intense and the rivers overflow their banks and change course. Iraq also has some large lakes. Buhayrat ath Tharthar and Buhayrat ar Razazah are two large lakes about 50 miles from Baghdad. In southeast Iraq, along the Tigris and Euphrates and the Iranian border there is a large area of marshes.

The Sumerian cities of Ur, Nippur and Uruk and Babylon were built on the Euphrates. Bagdad (built long after Mesopotamia declined) and the Assyrian city of Ashur were built on the Tigris River.

Marshes of Eastern Mesopotamia

The marshes of modern Iraq (eastern Mesopotamia) the largest wetland in the Middle East and are believed by some to have been the source of the Garden of Eden story. A large, lush fertile oasis in a blistering hot desert, they originally covered 21,000 square kilometer (8,000 square miles) between the Tigris and Euphrates and extended from Nasiriya in the west to the Iranian border in the east and from Kut in the north to Basra in the south. The area embraced permanent marshes and seasonal marshes that flooded in the spring and dried up in the winter.

The marshes embrace lakes, shallow lagoons, reed banks, island villages, papyri, reed forests. and mazes of reeds and twisting channels. Much of the water is clear and less than eight feet deep. The water was regarded as clean enough to drink.The marshes are a stopover for migratory birds and home to unique wildlife, including the Euphrates soft-shell turtle, Mesopotamia spiny-tailed lizard, the Mesopotamian bandycoot rat, the Mesopotamian gerbil, and the smooth coated otter. There are also eagles, pied kingfishers, Goliath herons and lots of fish and shrimp in the water.

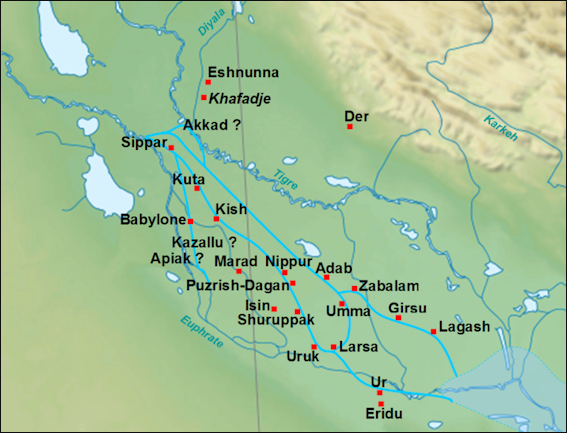

cities of Mesopotamia

The origin of the marshes is the subject of debate. Some geologists think they were once part of the Persian Gulf . Others think they were created by river sediment carried by the Tigris and Euphrates. The marshes have been home of the Marsh Arabs for at least 6000 years.

Mesopotamia Marshes, Sumerians and Marsh Arabs

N. Al-Zahery wrote: “For millennia, the southern part of the Mesopotamia has been a wetland region generated by the Tigris and Euphrates rivers before flowing into the Gulf. This area has been occupied by human communities since ancient times and the present-day inhabitants, the Marsh Arabs, are considered the population with the strongest link to ancient Sumerians. Popular tradition, however, considers the Marsh Arabs as a foreign group, of unknown origin, which arrived in the marshlands when the rearing of water buffalo was introduced to the region. [Source: In search of the genetic footprints of Sumerians: a survey of Y-chromosome and mtDNA variation in the Marsh Arabs of Iraq.Al-Zahery N, et al. BMC Evol Biol. 2011 Oct 4;11:288 ||||]

The Mesopotamian civilization originated around the 4th millennium B.C. in the low course of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. This alluvial territory, which emerged progressively by soil sedimentation, attracted different populations from the northern and eastern mountains but, whereas traces of their culture are present in the territory, as documented by the Ubaid-Eridu pottery, nothing is available for their identification. Only two groups of populations arrived later and in larger number leaved historical records: Sumerian and Semitic groups. The Sumerians, who spoke an isolated language not correlated to any linguistic family, are the most ancient group living in the region for which we have historical evidence. They occupied the delta between the two rivers in the southern part of the present Iraq, one of the oldest inhabited wetland environments. The Semitic groups were semi-nomadic people who spoke a Semitic language and lived in the northern area of the Syro-Arabian desert breeding small animals. From here, they reached Mesopotamia where they settled among the pre-existing populations. The Semitic people, more numerous in the north, and the Sumerians, more represented in the south, after having adsorbed the pre-existing populations, melted their cultures laying the basis of the western civilization [1].

The Mesopotamian marshes are among the oldest and, until twenty years ago, the largest wetland environments in Southwest Asia, including three main areas: :1): the northern Al-Hawizah, 2) the southern Al-Hammar and 3) the so-called Central Marshes all rich in both natural resources and biodiversity. However, during the last decades of the past century, a systematic plan of water diversion and draining drastically reduced the extension of the Iraqi marshes, and by the year 2000 only the northern portion of Al-Hawizah (about 10 percent of its original extension) remained as functioning marshland whereas the Central and Al-Hammar marshes were completely destroyed. This ecological catastrophe constrained Marsh Arabs of the drained zones to leave their niche: some of them moved to the dry land next to the marshes and others went in diaspora. However, due to the attachment to their lifestyle, Marsh Arabs have been returned to their land as soon as the restoration of marshes began (2003)

Dalmaj marsh in Iraq

“The ancient inhabitants of the marsh areas were Sumerians, who were the first to develop an urban civilization some 5,000 years ago. Although footprints of their great civilization are still evident in prominent archaeological sites lying on the edges of the marshes, such as the ancient Sumerian cities of Lagash, Ur, Uruk, Eridu and Larsa, the origin of Sumerians is still a matter of debate. With respect to this question, two main scenarios have been proposed: according to the first, the original Sumerians were a group of populations who had migrated from “the Southeast” (India region) and took the seashore route through Arabian Gulf before settling down in the southern marshes of Iraq The second hypothesis posits that the advancement of the Sumerian civilization was the result of human migrations from the mountainous area of Northeastern Mesopotamia to the southern marshes of Iraq, with ensuing assimilation of the previous populations. ||||

“Over time, the many historical and archaeological expeditions that have been conducted in the marshes have consistently reported numerous parallelisms between the modern and ancient life styles of the marsh people. Details such as home architecture (particular arched reed buildings), food gathering (grazing water buffalos, trapping birds and spearing fish, rice cultivation), and means of transportation (slender bitumen-covered wooden boats, called “Tarada”) are documented as still being practiced by the indigenous population locally named “Ma’dan” or “Marsh Arabs”. This village life-style, which has remained unchanged for seven millennia, suggests a possible link between the present-day marsh inhabitants and ancient Sumerians. However, popular tradition considers the Marsh Arabs as a foreign group, of unknown origin, which arrived in the marshlands when the rearing of water buffalo was introduced to the region.” ||||

DNA Study on Links Between Marsh Arabs of Modern Iraq and Ancient Mesopotamians

N. Al-Zahery wrote: “To shed some light on the paternal and maternal origin of this population, the Male Specific region of the Y chromosome (MSY) and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) variation was surveyed in 143 Marsh Arabs and in a large sample of Iraqi controls. Analyses of the haplogroups and sub-haplogroups observed in the Marsh Arabs revealed a prevalent autochthonous Middle Eastern component for both male and female gene pools, with weak South-West Asian and African contributions, more evident in mtDNA. A higher male than female homogeneity is characteristic of the Marsh Arab gene pool, likely due to a strong male genetic drift determined by socio-cultural factors (patrilocality, polygamy, unequal male and female migration rates). [Source: In search of the genetic footprints of Sumerians: a survey of Y-chromosome and mtDNA variation in the Marsh Arabs of Iraq. Al-Zahery N, et al. BMC Evol Biol. 2011 Oct 4;11:288 ||||]

cities and states of the Mesopotamian area

“The sample consists of 143 healthy unrelated males, mainly from the Al-Hawizah Marshes (the only not drained South Iraqi marsh area. For comparison, a sample of 154 Iraqi subjects representative of the general Iraqi population and therefore referred throughout the text as “Iraqi” was investigated for both mtDNA and Y-chromosome markers. This sample, previously analysed at low resolution is mainly composed of Arabs, living along the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. In addition, the distribution of the Y-chromosome haplogroup (Hg) J1 sub-clades was also investigated in four samples from Kuwait (N = 53), Palestine (N = 15), Israeli Druze (N = 37) and Khuzestan (South West Iran, N = 47) as well as in more than 3,700 subjects from 39 populations, mainly from Europe and the Mediterranean area but also from Africa and Asia. ||||

“The screening of 45 SNPs, plus one identified in this survey, in Marsh Arabs and Iraqis identified 28 haplogroups, 14 in the marsh sample and 22 in the control Iraqis. Only eight haplogroups were shared by both groups... More than 90 percent of both Y-chromosome gene pools can be traced back to Western Eurasian components: the Middle Eastern Hg J-M304, the Near Eastern Hgs G-M201, E-M78 and E-M123, while the Eurasian Hgs I-M170 and R-M207 are scarce and less common in the Marsh Arabs than in the control sample. Contributions from eastern Asia, India and Pakistan, represented by Hgs L-M76, Q-M378 and R2-M124, are detected in the Marsh Arabs, but at a very low frequency. ||||

“Haplogroup J accounts for 55.1 percent of the Iraqi sample reaching 84.6 percent in the Marsh Arabs, one of the highest frequencies reported so far. Unlike the Iraqi sample, which displays a roughly equal proportion of J1-M267 (56.4 percent) and J2-M172 (43.6 percent), almost all Marsh Arab J chromosomes (96 percent) belongs to the J1-M267 clade and, in particular, to sub-Hg J1-Page08. Haplogroup E, which characterizes 6.3 percent of Marsh Arabs and 13.6 percent of Iraqis, is represented by E-M123 in both groups, and E-M78 mainly in the Iraqis. Haplogroup R1 is present at a significantly lower frequency in the Marsh Arabs than in the Iraqi sample (2.8 percent vs 19.4 percent; P 0.001), and is present only as R1-L23. Conversely the Iraqis are distributed in all the three R1 sub-groups (R1-L23, R1-M17 and R1-M412) found in this survey at frequencies of 9.1 percent, 8.4 percent and 1.9 percent, respectively. Other haplogroups encountered at low frequencies among the Marsh Arabs are Q (2.8 percent), G (1.4 percent), L (0.7 percent) and R2 (1.4 percent).” ||||

Evidence of genetic stratification ascribable to the Sumerian development was provided by the Y-chromosome data where the J1-Page08 branch reveals a local expansion, almost contemporary with the Sumerian City State period that characterized Southern Mesopotamia. On the other hand, a more ancient background shared with Northern Mesopotamia is revealed by the less represented Y-chromosome lineage J1-M267*. Overall our results indicate that the introduction of water buffalo breeding and rice farming, most likely from the Indian sub-continent, only marginally affected the gene pool of autochthonous people of the region. Furthermore, a prevalent Middle Eastern ancestry of the modern population of the marshes of southern Iraq implies that if the Marsh Arabs are descendants of the ancient Sumerians, also the Sumerians were most likely autochthonous and not of Indian or South Asian ancestry.” ||||

Mesopotamia in 2300 B.C.

Near East and Middle East

These days many people think of the Middle East as embracing the countries of Arab countries of Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Yemen, Oman, and Iraq. Some people also include Cyprus, Turkey, Israel and Iran, and a lesser degree Afghanistan, which are all not Arab. Sometimes Libya is included in the Middle East but is generally thought of being in North Africa. Sometimes Sudan and Mauritania are included but is generally thought of being in Africa.

The Near East was traditionally used to describe the region between the eastern shores of the Mediterranean to present-day Afghanistan. The Near East was commonly used to describe the region until the 1960s, when it started becoming more fashionable to use the term Middle East. The French and the U.S. State Department (2003) still use the term Near East. The United Nations used the term Near east, Middle East and West Asia.

Mesopotamian Sites in Iraq

Mesopotamian Sites in Iraq include: 1) Baghdad. Site of the National Museum of Iraq, which has the world's pre-eminent collection of Mesopotamian antiquities, including a 4,000-year-old silver harp from Ur and thousands of clay tablets. 2) The Arch at Ctesiphon. This hundred-foot arch on the outskirts of Baghdad is one of the tallest brick vaults in the world. A fragment of a 1,400-year-old royal palace, it was damaged during the gulf war. Scholars warn that its collapse is increasingly likely. [Source: Deborah Solomon, New York Times, January 05, 2003]

3) Nineveh. The third capital of Assyria. It is mentioned in the Bible as a city whose people live in sin. A whalebone hangs in the mosque on Nebi Yunis, said to be a relic from the adventures of Jonah and the whale. 4) Nimrud. Home of the Assyrian royal palace, whose walls cracked during the gulf war, and of the tombs of Assyrian queens and princesses, discovered in 1989 and widely considered the most significant tombs since King Tut's. 5) Samarra. Major Islamic site and religious center 70 miles north of Baghdad, very close to a main Iraqi chemical research complex and production plant. Home to a stunning ninth-century mosque and minaret that were hit by allied bombers in 1991.

6) Erbil. Ancient town, continuously inhabited for more than 5,000 years. It has a high ''tell,'' an archaeological marvel consisting of layered towns that were built one on top of the other over thousands of years. 7) Nippur. Major religious center of the south, well stocked with Sumerian and Babylonian temples. It is fairly isolated and thus less vulnerable to bombs than other towns. Ur) Supposedly the world's first city. Peaked around 3500 B.C. Ur is mentioned passingly in the Bible as the birthplace of the patriarch Abraham. Its fantastic temple, or ziggurat, was damaged by allied troops during the gulf war, which left four massive bomb craters in the ground and some 400 bullet holes in the walls of the city.

9) Basra Al-Qurna. Here, a gnarled old tree, supposedly Adam's, stands on the supposed Garden of Eden. 10) UrUk. Another Sumerian city. Some scholars say it is older than Ur, dating to at least 4000 B.C. Local Sumerians invented writing here in 3500 B.C. 11) Babylon. The city reached the height of its splendor during the reign of Hammurabi, around 1750 B.C., when he developed one of the great legal codes. Babylon is only six miles from Iraq's Hilla chemical arsenal.

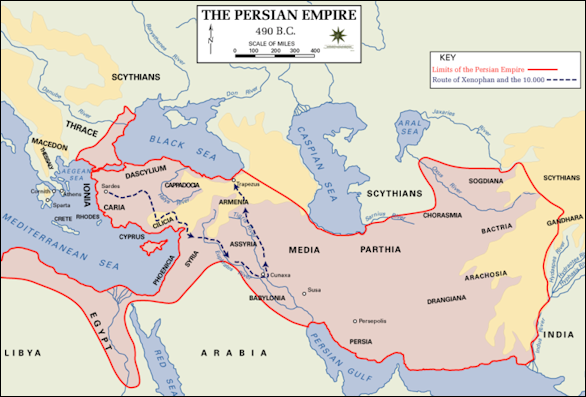

Mesopotamia in 490 B.C.

Weather and Climate in Mesopotamia

The weather in Mesopotamia was no doubt similar to the weather in Iraq today. In Iraq the weather in Iraq varies according to elevation and location but generally is mild in the winter, very hot in the summer and dry most of the year except for a brief rainy period in the winter. Most of the country has a desert climate. The mountainous areas have temperate climates. Winter and to a lesser extent spring and autumn are pleasant in much of the country.

Precipitation is generally scarce in most of the Iraq and tends to fall between November and March, with January and February generally being the rainiest months. The heaviest precipitation usually falls in the mountains and on the windward western sides of the mountains. Iraqi receives relatively little rain because the mountains in Turkey, Syria and Lebanon block the moisture carried by winds from the Mediterranean Sea. Very little rain comes in from the Persian Gulf.

In the desert regions rainfall can vary greatly from month to month and year to year. The amount rainfall generally diminishes as one travels westward and southward. Baghdad gets only about 10 inches (25 centimeters) of rain a year. The barren deserts in the west get around 5 inches (13 centimeters) . The Persian Gulf area receives little rain but can oppressively humid and hot. Iraq suffers from occasional droughts.

Iraqi can get very windy and experience nasty sandstorms, particularly in the central plains in the spring. Low pressure in the Persian Gulf generates regular wind patterns, with Persian Gulf and much of Iraq receiving prevailing northwesterly winds. The “shamal” and “sharqi” winds blows from northwest through the Tigris and Euphrates Valley from March until September. These winds bring cool weather and can reach speeds of 60mph and kick up fierce sandstorms. In September, the humid “date wind” blows off the Persian Gulf and ripens the date crop.

Winter in Iraq is mild in most of the country, with high temperatures in the 70s F (20s C), and cold in the mountains, where the temperatures often plummet to below freezing and cold rain and snow may occur. Steady, strong winds blow consistently. Baghdad is reasonably pleasant. January is generally the coolest the month. Snow in the mountainous areas tends to fall in squalls and flurries rather than storms although severe blizzards do occur from time to time. The snow on the ground tends to be icy and crusty. In the mountains snow can accumulate to great depths.

Summer in Iraq is very hot throughout the country, with exception of the high mountains. There is generally no rain. In most of Iraq the highs are in the 90s and 100s (upper 30s and 40s C). The deserts are extremely hot. Temperatures often rises above 100̊F (38̊C) or even 120̊F (50̊C) during the afternoon and then sometimes drop into the 40s F (single digits C) at night. In the summer Iraq is scorched by brutal southern winds. The Persian Gulf area is very humid. Baghdad is very hot but not humid. June, July and August are the hottest months.

Environment in Mesopotamia

Wood was scarce and forests were far away. In Babylonian times Hammurabi instituted the death penalty for illegal timber harvesting after wood became so scarce that people took their doors with them when they moved. The shortages also resulted in the degradation of agriculture land and cut production of chariots and naval ships.

Large amounts of silt carried down by the Tigris and Euphrates caused water levels in the rivers to rise. Technical problems posed by the large amount of silt and rising water levels included building higher and higher levees, dredging large amounts of slit, the blockage of natural drainage channels, creating channels to release floods and the building of dams to control floods.

The Mesopotamia kingdoms were ravaged by wars and hurt by changing watercourse and the salinization of farmland. In the Bible the Prophet Jeremiah said Mesopotamia’s “cities are a desolation, a dry land, and a wilderness, a land wherein no man dwelleth, neither doth any son of man pass thereby." Today wolves scavenge in the wastelands outside of Ur.

The early Mesopotamian civilizations are believed to have fallen because salt accruing from irrigated water turned fertile land into a salt desert. Continuous irrigation raised the ground water, capillary action — the ability of a liquid to flow against gravity where liquid spontaneously rises in a narrow space such as between grains of sand and soil — brought the salts to the surface, poisoning the soil and make it useless for growing wheat. Barley is more salt resistant than wheat. It was grown in less damaged areas. The fertile soil turned to sand by drought and the changing course of the Euphrates that today is several miles away from Ur and Nippur.

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2025