Home | Category: Muhammad and the Arab Conquest / Pre-Islamic Arabia / Muhammad / Mosques, Mecca and Muslim Holy Places / The Hajj / Pre-Islamic Arabian and Middle Eastern History / Muhammad

MECCA IN MUHAMMAD’S TIME

Muhammad arriving in Mecca

Muhammad was born in Mecca at a time when the city was establishing itself as a trading center. For the residents of Mecca, tribal connections were still the most important part of the social structure. Muhammad was born into the Quraysh, which had become the leading tribe in the city because of its involvement with water rights for the pilgrimage. By the time of Muhammad, the Quraysh had become active traders as well, having established alliances with tribes all over the peninsula. These alliances permitted the Quraysh to send their caravans to Yemen and Syria. Accordingly, the Quraysh represented in many ways the facilitators and power brokers for the new status quo in Arabian society. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Saudi Arabia: A Country Study, U.S. Library of Congress, 1992]

Maxime Rodinson wrote in “Muhammad”: “Mecca lies in a gorge in a range of mountains running parallel to the coast. The mountains are black and yellow, 'unbelievably bare, rocky crags with no scrap of soil, sharp, jagged, broken edges, sheer from top to bottom'. The valley, which runs in a north-easterly direction, has been carved out by a wadi which, in particularly violent rainstorms, still overflows from time to time, flooding the city and its shrine so that the pilgrims have to swim their way out - as happened for instance in I950. In this arid but well-placed valley, some fifty miles from the sea, is the famous well of Zamzam. The place may have been a sanctuary of long standing. The geographer Ptolemy, in the second century, described the region as the site of a place he called Makoraba. This could well be a transliteration of the word written in South Arabian characters (which omit the vowel sounds) as mkrb, in Ethiopic mekwerab, meaning 'sanctuary', from which perhaps, by abbreviation, we get the historical name of the city. [Source: Maxime Rodinson (1915-2004), “Muhammad,” Pantheon Books, 1980, Beginning with pp. 38, sourcebooks.fordham.edu ^\^]

“At some date - not known to us - Mecca became a trading centre, probably as a result of its admirable situation at the junction of a road going from north to south, from Palestine to the Yemen, with others from east to west, connecting the Red Sea coast and the route to Ethiopia with the Persian Gulf. The sanctuary ensured that the merchants would not be molested. It was held initially by the tribe of Jurhum and afterwards passed into the hands of the Khuza'a. ^\^

Websites on Islamic History: History of Islam: An encyclopedia of Islamic history historyofislam.com ; Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World oxfordislamicstudies.com ; Sacred Footsetps sacredfootsteps.com ; Islamic History Resources uga.edu/islam/history ; Internet Islamic History Sourcebook fordham.edu/halsall/islam/islamsbook ; Islamic History friesian.com/islam ; Muslim Heritage muslimheritage.com ; Chronological history of Islam barkati.net ; Muhammad: Encyclopædia Britannica britannica.com ; Muhammad: Legacy of a Prophet — PBS Site pbs.org/muhammad ; Prophet Muhammad prophetmuhammad.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Mecca the Blessed, Medina the Radiant: The Holiest Cities of Islam” by Ali Kazuyoshi Nomachi and Seyyed Hossein Nasr Ph.D. Amazon.com ;

“Mecca: The Sacred City” by Ziauddin Sardar, Amerjit Deu, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Muhammad: A Prophet for Our Time” by Karen Armstrong Amazon.com ;

“Muhammad: His Life Based on the Earliest Sources” by Martin Lings Amazon.com ;

“Revelation: The Story Of Muhammad” by Meraj Mohiuddin Amazon.com ;

“Islam, a Short History “ by Karen Armstrong Amazon.com ;

“Islam Explained: A Short Introduction to History, Teachings, and Culture” by Ahmad Rashid Salim Amazon.com ;

“Life of the Sahaabah (RA): True companions of the Prophet Muhammad [PBUH]” by Sheikhul Hadeeth Hadhrat Moulana Muhammad Zakariyya Amazon.com ;

“The Cambridge Companion to Muhammad” by Jonathan E. Brockopp Amazon.com

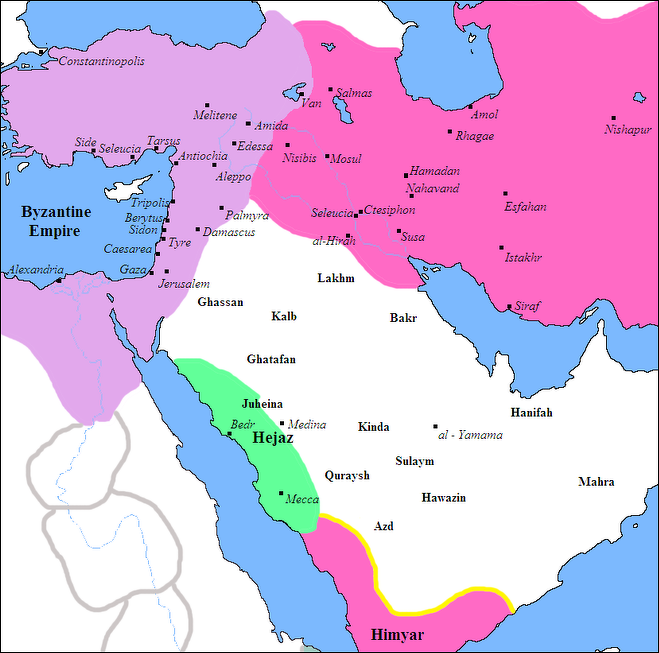

Middle East in Muhammad's Time

reconstruction of a Pre-Islamic Arabian town

Muhammad lived around 600 years after Jesus and 200 years after the collapse of Rome. Arabia was located in the broader Near East, which was divided between two warring superpowers, the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) and the Sasanian (Persian) empires, that were competing for dominion of their known worlds. The Byzantines were Christians and the Persian Sassanids were Zoroastrians.

In seventh-century Arabia, where Muhammad was born, war and tribal conflicts were not out of the ordinary. Located along the profitable trade routes, Arabia was affected by the rivalry and interventions by the Byzantines and Persians. But for the most part Arabiawas a desert backwater. The frankincense trade that once enriched it was long past its peak Many Arabs were caught up in a cycle of violence and warfare in which tribes fought each other in a never ending series of vendettas and blood feuds. Almost everyone was illiterate.

Archaeology magazine reported: According to historical sources, people have long eaten Arabian spiny-tailed lizards. According to tradition, Muhammad did not eat them himself, but did not condemn the practice. At the site of al-Yamâma, archaeologists uncovered remains of lizards among those of other food animals, and at least one bone has a cut mark. The lizard bones appear in early layers (4th to 7th century, before and just after the establishment of Islam) and continue to the 18th century. The reptiles remain a source of protein and fat in some parts of the harsh desert today. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2014]

Mecca was a major commercial center with large pagan, Jewish and Christian communities. Situated at the center of a network of ancient caravan routes, it drew traders from all over the Middle East and hosted trade fairs. It owed its success to it connection with religion. Violence was not tolerated and people were forbidden from carry weapons, thus traders and merchants were able to conduct business with relatively few worries.

Mecca owed its position to hostility between the Persians and Byzantines, which cut off much of the Silk Road trade, meaning that goods from China, India and the Orient came across the sea to Yemen and then the cities of the Middle East, often via caravan routes that passed through Mecca.

Arabs and Tribalism in Muhammad's Time

The word Arab in the Qur’an is used primarily to describe camel-herding pastoral Bedouin tribes of the Arabian peninsula. Nomadic Arab tribes made up a small proportion of the total population of what is now Arabia but appear to have been important as a political and cultural force. They produced rich oral literature and poetry and their lifestyle was regarded as a cultural ideal by some. Others looked own on them. The word Arab was used in a pejorative sense by farmers and townspeople who didn’t regard themselves as Arabs and considered Bedouins to be primitive.

Bedouin

In Muhammad’s time, Arab identity brought with it membership into an all-encompassing patrilineal descent system that brought recognition, honor and certain privileges, such as exemptions from some taxes. Close association with genealogical origins has prevented Arab societies from assimilating non-Arabs into Arab society, a practice that has held true throughout Arab history.

Most Arabs were either Bedouins or towns people. There weren’t that many farmers in the harsh desert except around oases. Townspeople were widely influenced by Bedouin values. Muhammad was a townsperson but his tribe, the Quaraysh, included many Bedouins, and towns people were widely influenced by them.

John L. Esposito wrote in the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”: Pre-Islamic Arabia was tribal in its religious, social, and political ideas, practices, and institutions. Tribal and family honor were central virtues. Manliness (chivalry, upholding tribal and family honor, and courage in battle) was a major virtue celebrated by the poets of the time. There was no belief in an afterlife or a cosmic moral purpose or in individual or communal moral responsibility. Thus, justice was obtained and carried out through group vengeance or retaliation. Arabia and the city of Mecca, in which Muhammad was born and lived and received God's revelation, were beset by tribal raids and cycles of vendettas. Raiding was an integral part of tribal life and society and had established regulations and customs. Raids were undertaken to increase property and such goods as slaves, jewelry, camels, and live-stock. Bloodshed was avoided, if at all possible, because it could lead to retaliation. [Source: John L. Esposito “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices”, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Quraysh Tribe and Mecca

Maxime Rodinson wrote in “Muhammad”: “Towards the end of the fifth century, perhaps, a strong man by the name of Qusayy succeeded either by force or trickery in gaining control of the temple. He belonged to the tribe of Quraysh, an assemblage of several clans which, through him, supplanted the Khuza'a. There may be some foundation of truth in the story that Qusayy had travelled in Syria, and had brought back from there the cult of the goddesses al- 'Uzza and Manat, and had combined it with that of Hubal, the idol of the Khuza'a. It has been suggested that he may actually have been a Nabataean. [Source: Maxime Rodinson, “Muhammad,” Pantheon Books, 1980, Beginning with pp. 38, sourcebooks.fordham.edu ^\^]

“In this way, Quraysh (the name means ' shark ' and may have been derived from an ancient tribal emblem) acquired an ascendancy which was to grow unceasingly; and the history of the ensuing five hundred years may be seen in the light of the expansion of this one tribe to the dimensions of a world power. Quraysh was in fact composed of a number of individual clans. They were known as the Quraysh az-Zawahir, the 'outer Quraysh ', who dwelt on the periphery, and the Quraysh al-Bata'ih, who settled in the valley bottom, immediately around the well of Zamzam and the curious shrine which stood beside it. This was like a small house, in the shape of a square box, called the Ka'ba, which means the cube. The object of especial veneration was a black stone, of meteoric origin, which may have been the cornerstone. Stones of this kind were worshipped by Arabs in most parts and by the Semitic races generally. When the young Syrian Arab Elagabalus, High Priest of the Black Stone of Emesa, was Emperor of Rome in 2I9, he had the holy thing transported solemnly to Rome and built a temple for it, much to the horror of the old Romans. The Ka'ba at Mecca, which may have initially been a shrine of Hubal alone, housed several idols; a number of others, too, were gathered in the vicinity. ^\^

“Later tradition tells how the four chief sons of 'Abd Manaf, one of Qusayy's sons, divided among themselves the areas where trade could be developed. One went to the Yemen, another to Persia, the third to Ethiopia and the fourth to Byzantine Syria. The tale is probably only legend, but it does reflect the truth. The Banu Quraysh did everything possible to foster the commercial development of their city. As we have seen, they were assisted by outside events. By about the end of the sixth century, their efforts had been rewarded by something like a position of commercial supremacy. Their caravans travelled far and wide to the cardinal points of international trade, represented by the four areas mentioned earlier. The chief merchants of Mecca had grown very rich. Mecca itself had become a meeting-place for merchants of all nations, and a fairly large number of craftsmen were to be found there. The holy place was attracting a growing number of pilgrims, who performed complicated rituals around the Ka'ba and the other small shrines round about. Judicious marriage alliances assured Quraysh of the support of the neighbouring nomadic tribes. There can be no doubt that money and, where necessary, arms provided an added incentive for friendship.

“Inevitably, the Qurayshite clans were struggling for supremacy amongst themselves. The principal ones to come to the fore were the clans of Hashim and 'Abd Shams, both of whom were sons of 'Abd Manaf. Hashim's son, 'Abd alMuttalib, seems to have had the upper hand at one time, at approximately the date of Muhammad's birth; but Hashim lost it before long to the family of Umayya, the son of 'Abd Shams. ^\^

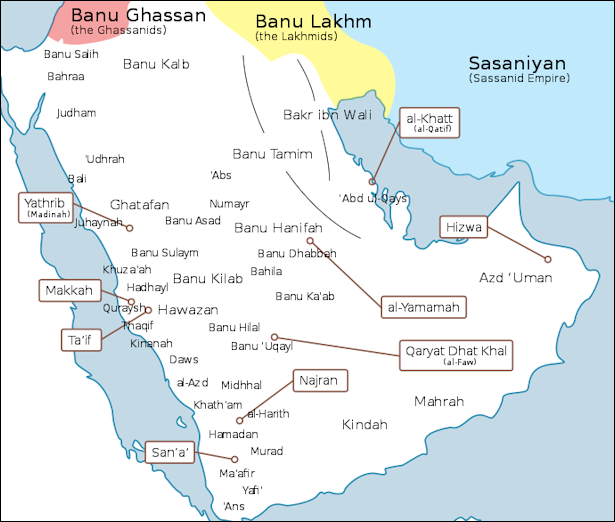

Arabian tribes around Muhammad's time

Fighting Between Byzantium and Persia in Muhammad’s Time

War sometimes broke out between the great powers of the day, Persia and Byzantium. To the 6th century historian, Procopius, a highly placed civil servant, its political and economic foundations were perfectly clear,Maxime Rodinson wrote in “Muhammad”: “ but in the eyes of the masses the struggle was first and foremost an ideological one. As we have seen, the war had begun again in 572; but in 591 the new Persian King of kings, Khusro II, called Abharwez, 'the Victorious', who had gained the throne with the aid of the Romans, had made peace on terms highly favourable to his protectors. Before long he was burning to get back what he had ceded. Khusro's friend, the basileus Maurice, had been deposed and killed in 602 by a revolt of the army which brought to power a brutal and quick-tempered officer named Phocas. The king of kings seized on this as an excuse for reopening the war. [Source: Maxime Rodinson (1915-2004), “Muhammad,” Pantheon Books, 1980, Beginning with pp. 38 ^\^]

“The Persians made rapid and astonishing progress. One army overran Roman Armenia, went on to invade Asia Minor and, in 610, its advance scouts reached the Bosphorus within sight of Constantinople. Another army moved into Syria, and the cities of northern Mesopotamia fell one after another. Antioch was under siege. The Monophysites of Syria were up in arms. The Jews took advantage of the confusion and of the Persian advance to take their revenge. Acting in collusion with the political and sporting anti-government faction, they killed the pro-imperial Patriarch of Antioch. Faced with imminent disaster, the malcontents raised to power another soldier, this time a man of real ability, Heraclius; he entered Constantinople in October 610. Phocas was put to death. While Heraclius was slowly gathering his army for the counterattack, the Persians continued their successful advance. Antioch fell in 611 and then, the ultimate disaster, on 5 May 614, the holy city of Jerusalem itself. The Patriarch and the inhabitants were taken into captivity, the churches burned and the most sacred relic of the True Cross removed with great ceremony to Ctesiphon. In 615 the Persian general Shahen took Chalcedon, across the strait from Constantinople. Between 617 and 619, the Persians occupied Egypt, the granary of the empire and of the capital in particular. The Avars and the Slavs were menacing in the west. Byzantium was at the lowest ebb. ^\^

“There were some Christians on the Persian side. Khusro had a favourite, a Christian girl from Syria whose name was Shiren; the story of their love has provided material for endless romances in every language of the Muslim east. The Nestorians continued to support him. His high treasurer, Yazden, was a Christian who was constantly building churches and monasteries. The Monophysites, who were the dominant sect in Syria and Egypt, if they did not actually help the Persians because of their alliance with the Nestorians, made no effort to defend the empire. For two centuries at least they had been in a state of moral secession, religious differences serving to accentuate and bring out purely local difficulties such as the quasi-nationalist feelings of rebellion against Greek dominance, feelings which were encouraged by a progressive economic decline. However, viewed from a distance, it was the attitude of the Jews which more than anything gave the conflict, to some extent at least, the appearance of a war of religion. This was how the tale was told with embellishments in distant Gaul. ^\^

Middle East at the time of Muhammad, with the Byzantine Empire in purple to the top left and the Persian Sassanid Empire to the top right in purplish pink

“A Burgundian chronicler, writing some thirty or forty years after the event, described Heraclius as 'pleasant to look on, with a handsome face, tall and very active and a valiant warrior. Alone and unarmed, he would often kill lions in the arena and wild boars in remote places.' When the Persians came in sight of his capital, he proposed to their emperor, Cosdroes, to settle the quarrel by single combat. Cosdroes sent a gallant nobleman to fight for him; Heraclius killed him by a cunning trick, whereupon the Persians fled. But Heraclius was ' well versed in letters ', and had therefore studied astrology. Thanks to this art he had learned that his empire would be devastated by peoples who practised circumcision. Concluding that this must refer to the Jews, he ' sent to Dagobert, king of the Franks, to entreat him to give orders that all the Jews in his realm should be baptized in the Catholic faith; this Dagobert instantly performed. Heraclius ordered that the same thing should be done throughout all the imperial provinces; for he had no idea whence this scourge would come upon his empire.'

Did Meccan Trade Help the Rise of Islam?

Patricia Crone wrote in “Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam”: According to the scholar W. Montgomery Watt, “the Qurashi transition to a mercantile economy undermined the traditional order in Mecca, generating a social and moral malaise to which Muhammad's preaching was the response.” Meccan trade “had in effect united most of Arabia already, numerous tribes having acquired an interest in the conduct of Meccan trade as well as in the maintenance of the sanctuary; inasmuch as the interests of Mecca and Arabia at large had come to coincide, Muhammad's conquest of Mecca amounted to a conquest of most of Arabia, though the process of unification was only to be completed on the suppression of the ridda. But though it is true that the suppression of the ridda completed the process, this is not an entirely persuasive explanation. If the interests of Mecca and the Arabs at large had come to coincide, why did the Arabs fail to come to Mecca's assistance during its protracted struggle against Muhammad? Had they done so, Muhammad's statelet in Medina could have been nipped in the bud. Conversely, if they were happy to leave Mecca to its own fate, why should they have hastened to convert when it fell? In fact, the idea of Meccan unification of Arabia rests largely on Ibn al-Kalbl's tl-tradition, a storyteller's yarn. No doubt there was a sense of unity in Arabia, and this is an important point; but the unity was ethnic and cultural, not economic, and it owed nothing to Meccan trade. [Source: Patricia Crone, “Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam,” Princeton University Press. 1987. Beginning with pg. 231 |-| sourcebooks.fordham.edu ]

This hypothesis is clearly weakened by the discovery that the Meccan traded in humble products rather than luxury goods, but it is not necessarily invalidated thereby. Even so, however, there are other reasons why it should be discarded.“In the first place, it is unlikely that so brief a period of commercial the nineteenth century, for example, the town of Ha'il enjoyed a meteoric rise to commercial importance, comparable to that described for Mecca, without there being any indication of a correspondingly swift breakdown of traditional norms. Why should there have been? It takes considerably more than a century of commercial success to undermine the tribal order of a population that has been neither uprooted nor forced to adopt a different organization in connection with its economic activi- ties. Caravan trade is not capitalist in any real sense of that word, and Watt's vision of the Meccans as financiers dedicated to a ruthless pursuit of profit occasionaly suggests that he envisages them as having made a transition to the twentieth century . |-|

Map of Arabia 600 AD

“In the second place, the evidence for a general malaise in Mecca is inadequate. According to Watt, the Qur'an testifies to an increasing awareness of the difference between rich and poor and a diminishing concern on the part of the rich for the poor and weak even among their own kin, orphans in particular being ill-treated; further, the Qur'anic stress on acts of generosity implies that the old ideal of generosity had broken down to the point that the conduct of the rich would have been looked upon as shameful in the desert, while at the same time the Qur'anic emphasis on man's dependence on God suggests that the Meccans had come to worship a new ideal, "the supereminence of wealth." But the Qur'an does not testify to an increasing awareness of social differentiation or distress: in the absence of pre-Qur'anic evidence on the subject, the book cannot be adduced as evidence of change.

Religion in Muhammad’s Time

Muhammad lived in Mecca in the 6th and 7th centuries at a time when the city was establishing itself as a trading center. Most Arabs were pagans who worshiped tribal deities. They had no sacred book or central religious figure. Many people were aware of Christianity and Judaism and belief in one God. There were Jewish and Christian communities in Arabia and Muhammad reportedly knew of but had not read the Bible or the Torah.

Mecca was major religious center long before Islam. Members of desert tribes went on pilgrimages to Mecca just like today's Muslims do. "In the 'Days of Ignorance' before Islam," the Qur’an reads, "regularly tribesmen come from all over Arabia to pay homage to the pantheon." They paid a fee to see the Kaaba, a great shrine officially dedicated to the Nabatean deity Hubal and venerated as the shrine for the high God Allah.

Arabs worshiped a Zeus-like god named Allah that was superior to all others. Many of their most respected religious leaders were described as “hanifs” of descendants of Abraham. There was supposedly a great deal of religious discontent in Arabia at the time Muhammad was born, with Jews and Christians taunting Arabs for being backward and left out of God’s divine plan.

See Separate Article: RELIGION IN MUHAMMAD’S TIME africame.factsanddetails.com

Six-Century Christian Monastery Found in the U.A.E.

In November 2022, archaeologist announced they had found a Christian monastery dated to the A.D. six century buried underneath the sand on Al Siniyah Island, situated off the coast of the United Arab Emirates mainland in the Persian Gulf according to a news release from the Tourism and Archaeology Department in Umm Al Quwain. The Miami Herald reported: The monastery is only the second of its kind found in the country and sixth ancient monastery to be found in the Arabian Gulf. The sand dunes revealed the ruins of multiple community buildings and a church, archaeologists said. [Source: Aspen Pflughoeft, Miami HeraldNovember 4, 2022] .

The floor plan of the ruins appeared to include a baptismal font, an altar with a spot for communion wine and an oven for baking bread used during communion, archaeologists told the Associated Press. The structures were built from local beach rocks, researchers said. The walls and floors were covered in lime plaster to make them more water resistant. The complex included a circular-shaped building, likely used as a cistern, the release said. Archaeologists also found pottery, glass fragments and coal samples. Analyzing these, researchers found that the monastery dated from the late sixth century to the middle of the eighth century and had trade links from Iraq to India.

Researchers told the Associated Press that the monastery was founded between 534 and 656 A.D. Many tribes in the Arabian Gulf were Christian before the founding of Islam in 610 and its rapid spread throughout the region in the following centuries, experts said. The discovery of the ancient monastery reveals more about the UAE’s rich history of diverse religious communities. The community living at this monastery likely saw the birth and rise of Islam, archaeologists said. Timothy Power, an associate professor of archaeology at the United Arab Emirates University, told the Associated Press that the monastery is “a really fascinating discovery because in some ways it’s hidden history — it’s not something that’s widely known.” Archaeologists have just completed their first phase of excavations and will begin work on the next phase, the release said. Al Siniyah Island is about 45 miles northeast of Dubai in the Emirate, or state, of Umm Al Quwain.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994). Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, BBC, Al Jazeera, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024