Home | Category: Pre-Islamic Arabian and Middle Eastern History / Pre-Islamic Arabia / Pre-Islamic Arabian and Middle Eastern History

ANCIENT ARAB AND MIDDLE EASTERN HISTORY

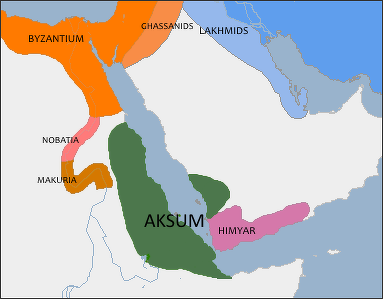

kingdoms and states in Arabia and the area around it in pre-Islamic times

The Middle East is the source of three of the world’s great religions—Judaism, Christianity and Islam—and the home of the ancient Egyptian and Mesopotamian cultures, The Seven Wonders of the World were in the Middle East and the first alphabet, first writing, first school, first calendar and the first code of laws originated there. The world oldest city (Jericho) and oldest continuously-inhabited city (Damascus) are there as well as most of the places mentioned in the Bible.

Arabs are relative latecomers to the Near East. They are first mentioned in the mid 9th century B.C. as a tribal people subjugated by the Assyrians. However, the Arabian Peninsula has a rich, largely unexplored ancient history. It is peppered with ancient kingdoms linked caravan routes that carried frankincense to the Mediterranean that attracted the attention of Romans among others. Ancient Arab peoples — such as the Nabateans, Lihyans and Thamud — interacted with Assyrians and Babylonians, Romans and Greeks.

Taima is an ancient city in northwest that was founded by a neo-Babylonian king around 800 B.C. It embraces a palace, 10-kilometer wall and a well that still provides water. Qaryat al Fau (110 miles north of Najran) is a city that existed around the same time on the edge of the Empty Quarter. Extensive excavations here have revealed a market palace, wall paintings, bronze statues, rich tombs full of inscriptions and evidence of trade with the Egyptians and Assyria.

Coastal towns developed on trade routes and fishing areas but sources of water and food were not large enough to allow ports to develop into cities. The Lihyanites of the Kingdom of Dedan in northwest Arabia carved lion reliefs above sandstone tombs in 600 B.C.

By 1000 B.C., southern Arabia had evolved significantly as a result of steady contact with the outside world via the trade routes that spanned the region. Exports in frankincense and myrrh brought wealth and global connections to present-day Bahrain, Yemen, Oman, and southern Saudi Arabia. While the Persians and Romans fought to control the Near East, Arab society benefited from the exchange of ideas that came with the camel caravans. Multiple religions were present in the region, including Christianity, Judaism, and various polytheistic paganisms. [Source: Library of Congress, September 2006 **]

See Separate Article ANCIENT ARAB AND MIDDLE EASTERN HISTORY factsanddetails.com; ANCIENT SOURCES ON ARABS AND THE MIDDLE EAST factsanddetails.com; BEDOUINS factsanddetails.com

Islamic History: History of Islam: An encyclopedia of Islamic history historyofislam.com ; Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World oxfordislamicstudies.com ; Sacred Footsetps sacredfootsteps.com ; Islamic History Resources uga.edu/islam/history ; Internet Islamic History Sourcebook fordham.edu/halsall/islam/islamsbook ; Islamic History friesian.com/islam ; Muslim Heritage muslimheritage.com ; Chronological history of Islam barkati.net

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam” by Robert G. Hoyland Amazon.com ;

“Pre-Islamic Arabia: Societies, Politics, Cults and Identities during Late Antiquity”

by Valentina A. Grasso Amazon.com ;

“Inscriptional Evidence of Pre-Islamic Classical Arabic: Selected Readings in the Nabataean, Musnad, and Akkadian Inscriptions” by Saad D Abulhab Amazon.com ;

“The Ancient Near East: A Very Short Introduction” by Amanda H. Podany, Fajer Al-Kaisi, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Weavers, Scribes, and Kings: A New History of the Ancient Near East”

by Amanda H. Podany a Amazon.com ;

“The Nabataeans: Builders Of Petra” by Dan Gibson Amazon.com ;

“Petra and the Lost Kingdom of the Nabataeans” by Jane Taylor Amazon.com ;

“Gold, Frankincense, Myrrh, And Spiritual Gifts Of The Magi” by Winston James Head Amazon.com ;

“Frankincense & Myrrh: Through the Ages, and a complete guide to their use in herbalism and aromatherapy today” by Martin Watt and Wanda Sellar Amazon.com ;

”History of the Arab People” by Albert Hourani(1991) Amazon.com ;

"Arabian Sands” (Penguin Classics) by Wilfred Thesiger Amazon.com

Trade in Pre-Islamic Period Arabia

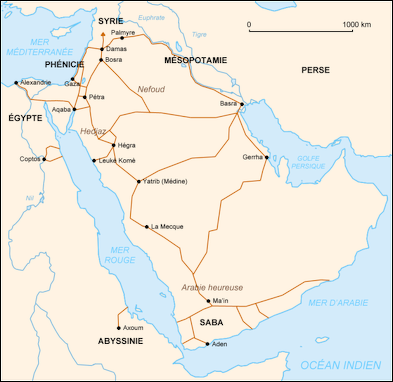

Trade routes in pre-Islamic times

The bodies of water on either side of the Arabian Peninsula provided relatively easy access to the neighboring river-valley civilizations of the Nile and the Tigris-Euphrates. Once contact was made, trading could begin, and because these civilizations were quite rich, many goods passed between them. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Saudi Arabia: A Country Study, U.S. Library of Congress, 1992 *]

The coastal people of Arabia were well-positioned to profit from this trade. Much of the trade centered around present-day Bahrain and Oman, but those living in the southwestern part of the peninsula, in present-day Yemen and southern Saudi Arabia, also profited from such trade. The climate and topography of this area also permitted greater agricultural development than that on the coast of the Persian Gulf.*

Generous rainfall in Yemen enabled the people to feed themselves, while the exports of frankincense and myrrh brought wealth to the area. As a result, civilization developed to a relatively high level in southern Arabia by about 1000 B.C. The peoples of the area lived in small kingdoms or city states of which the best known is probably Saba, which was called Sheba in the Old Testament. The prosperity of Yemen encouraged the Romans to refer to it as Arabia Felix (literally, "happy Arabia"). Outside of the coastal areas, however, and a few centers in the Hijaz associated with the caravan trade, the harsh climate of the peninsula, combined with a desert and mountain terrain, limited agriculture and rendered the interior regions difficult to access. The population most likely subsisted on a combination of oasis gardening and herding, with some portion of the population being nomadic or seminomadic.*

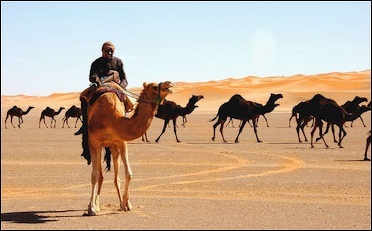

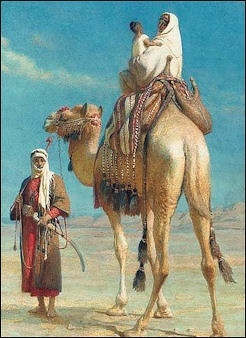

The material conditions under which the Arabs lived began to improve around 1000 B.C. A method for saddling camels had been developed to transport large loads. The camel was the only animal that could cross large tracts of barren land with any reliability. The Arabs could now benefit from some of the trade that had previously circumvented Arabia.*

Impact of Trade on Pre-Islamic Arabia

The increased trans-Arabian trade produced two important results. One was the rise of cities that could service the trains of camels moving across the desert. The most prosperous of these- -Petra in Jordan and Palmyra in Syria, for example — were relatively close to markets in the Mediterranean region, but small caravan cities developed within the Arabian Peninsula as well. The most important of these was Mecca, which also owed its prosperity to certain shrines in the area visited by Arabs from all over the peninsula. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Saudi Arabia: A Country Study, U.S. Library of Congress, 1992 *]

Some Arabs, particularly in the Hijaz, held some religious beliefs that recognized a number of gods as well as a number of rituals for worshiping them. The most important beliefs involved the sense that certain places and times of year were sacred and must be respected. At those times and in those places, warfare, in particular, was forbidden, and various rituals were required. Foremost of these was the pilgrimage, and the best known pilgrimage site was Mecca.*

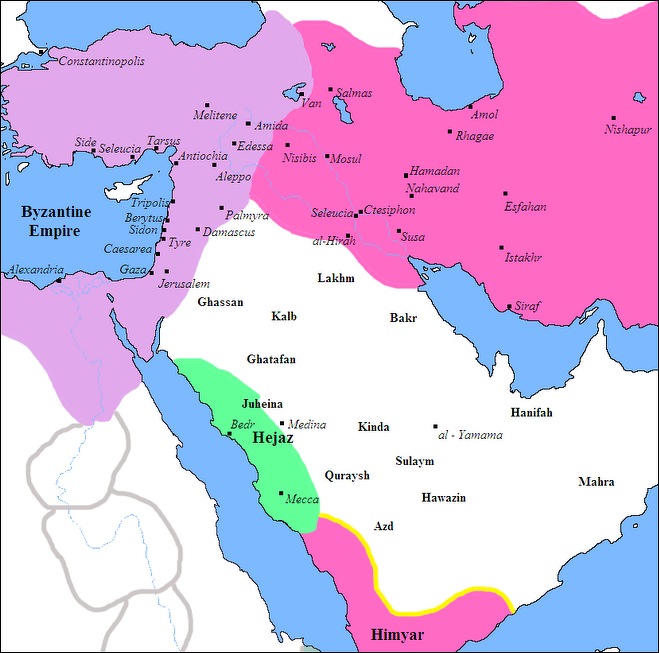

The second result of the Arabs' increased involvement in trade was the contact it gave them with the outside world. In the Near East, the Persians and the Romans were the great powers in centuries before the advent of Islam, and the Arab tribes that bordered these territories were drawn into their political affairs. After 400 A.D., both empires paid Arab tribes not only to protect their southern borders but also to harass the borders of their adversary.*

In the long term, however, it was the ideas and people that traveled with the camel caravans that were the most important. By 500 A.D., the traditional ritual of Arab worship was but one of a number of religious options. The Sabaeans of southern Arabia followed their own system of beliefs, and these had some adherents in the interior. Followers of pagan beliefs, as well as Hanifs, mentioned in the Quran and believed to be followers of an indigenous monetheistic religion, were widespread in the peninsula. In addition, there were well-established communities of Christians and Jews. Along the gulf coast were Nestorians, while in Yemen Syrian Orthodox and smaller groups of Christians were to be found among beduin and in monasteries that dotted the northern Hijaz. In the sixth century, shortly before the birth of Muhammad, the city of Najran in what is now southwestern Saudi Arabia had a Christian church with a bishop, monks, priests, nuns, and lay clergy, and was ruled by a Jewish king. Jews were an important part not only of the Yemeni population, but also of the oases communities in the region of Medina.*

Religion in Muhammad’s Time

Muhammad lived in Mecca in the 6th and 7th centuries at a time when the city was establishing itself as a trading center. Most Arabs were pagans who worshiped tribal deities. They had no sacred book or central religious figure. Many people were aware of Christianity and Judaism and belief in one God. There were Jewish and Christian communities in Arabia and Muhammad reportedly knew of but had not read the Bible or the Torah.

Mecca was major religious center long before Islam. Members of desert tribes went on pilgrimages to Mecca just like today's Muslims do. "In the 'Days of Ignorance' before Islam," the Qur’an reads, "regularly tribesmen come from all over Arabia to pay homage to the pantheon." They paid a fee to see the Kaaba, a great shrine officially dedicated to the Nabatean deity Hubal and venerated as the shrine for the high God Allah.

Arabs worshiped a Zeus-like god named Allah that was superior to all others. Many of their most respected religious leaders were described as “hanifs” of descendants of Abraham. There was supposedly a great deal of religious discontent in Arabia at the time Muhammad was born, with Jews and Christians taunting Arabs for being backward and left out of God’s divine plan.

See Separate Article: RELIGION IN MUHAMMAD’S TIME africame.factsanddetails.com

Archaeology in the Arabian Peninsula

Donna Abu-Nasra of Associated Press wrote: “Najran, discovered in the 1950s, was invaded nearly a century before Muhammad's birth by Dhu Nawas, a ruler of the Himyar kingdom in neighboring Yemen. A convert to Judaism, he massacred Christian tribes, leaving triumphant inscriptions carved on boulders. At nearby Jurash, a previously untouched site in the mountains overlooking the Red Sea, a team led by David Graf of the University of Miami is uncovering a city that dates at least to 500 B.C. The dig could fill out knowledge of the incense routes running through the area and the interactions of the region's kingdoms over a 1,000-year span. [Source: Donna Abu-Nasra, Associated Press, Sept. 1, 2009 \=]

“And a French-Saudi expedition is doing the most extensive excavation in decades at Madain Saleh. The city, also known as al-Hijr, features more than 130 tombs carved into mountainsides. Some 450 miles from Petra, it is thought to mark the southern extent of the Nabatean kingdom. In a significant 2000 find, Altalhi unearthed a Latin dedication of a restored city wall at Madain Saleh which honored the second century Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius. \=\ Christian Robin a leading French archaeologist and a member of the College de France, is working in the southwestern region of Najran, mentioned in the Bible by the name Raamah and once a center of Jewish and Christian kingdoms. No Christian artifacts have been found in Najran, he said.

“Excavations sometimes meet opposition from local residents who fear their region will become known as "Christian" or "Jewish.'' And Islam being an iconoclastic religion, hard-liners have been known to raze even ancient Islamic sites to ensure that they do not become objects of veneration. In 1986, picnickers accidentally discovered an ancient church in the eastern region of Jubeil. Pictures of the simple stone building show crosses in the door frame.” The 4th ot 5th century church “is fenced off – for its protection, authorities say – and archaeologists are barred from examining it. Faisal al-Zamil, a Saudi businessman and amateur archaeologist, says he has visited the church several times. He recalls offering a Saudi newspaper an article about the site and being turned down by an editor.” \=\

Arabs, Byzantium and Christianity in the A.D. 5th Century

Irfan Shahid wrote: “Of the three constituents of Byzantinism — the Roman, the Greek, and the Christian — it was the last that affected, influenced, and sometimes even controlled the lives of those Arabs who moved in the Byzantine orbit. Something has been said on this influence in the fourth century, and these conclusions may be refined and enlarged with new data for the fifth. [Source: Irfan Shahid. Byzantium and the Arabs in the Fifth Century, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library, Washington, D.C. 1989. Beginning with pg. 528, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu ]

“1. Christianity presented the Arabs with new human types unknown to them from their pagan and Peninsular life — the priest, the bishop, the martyr, the saint, and the monk — and the Arab community in Oriens, both Rhomaic and federate, counted all of them among its members. In the fourth century, it contributed one saint to the universal Church — Moses, whose feast falls on the seventh of February — and in the Roman period it had contributed Cosmas and Damian. In the fifth century the Arab episcopate grew in number, both Rhomaic and federate, as is clear from conciliar lists and from the number of Arab bishops compared to those of the fourth century. As a result, the Arab ecclesiastical voice was audible in church councils, and was at its most articulate at Ephesus in defense of Cyrillian Orthodoxy.

“2. The priesthood and the episcopate subjected the Arabs to a new form of authority and discipline to which they had not been accustomed. It was a spiritual form of authority, to which even the powerful federate phylarchs and kings were subject, and it thus induced in the Christian Arabs a new sense of loyalty which was supra-tribal, related not to tribal chauvinism but to the Christian ecclesia. This new loyalty was to find expression on the battlefield. The federate troops under their believing phylarchs fought the fire-worshiping Persians and the pagan Lakhmids with a crusading zeal, and they probably considered those who fell in such battles martyrs of the Christian faith.

Pre Islamic Arabia

“3. Christianity influenced the literary life of the Arabs in the fifth century as it had done in the fourth. The conclusions on this are mainly inferential, but less so for poetry than for prose. If there was an Arabic liturgy and a biblical lectionary in the fifth century, the chances are that this would have influenced the development of Arabic literary life, as it invariably influenced that of the other peoples of the Christian Orient. It is possible to detect such influences in the scanty fragments of Arabic poetry and trace the refining influence of the new faith on sentiments. Loanwords from Christianity in Arabic are easier to document, and they are eloquent testimony to the permanence of that influence in much the same way that other loanwords testify to the influence of the Roman imperim.

“4. By far the most potent influence of Christianity on the Arabs was that of monasticism. The new type of Christian hero after the saint and the martyr, the monk who renounced the world and came to live in what the Arabs considered their natural homeland, the desert, especially appealed to the Arabs and was the object of much veneration. The monasteries penetrated deep in the heart of Arabia, into regions to which the church could not penetrate. Thus the monastery turned out to be more influential than the church in the spiritual life of the Arabs, especially in the sphere of indirect Byzantine influence in the Peninsula. The monastery was also the meeting place of two ideals — Christian philanthropia and Arab hospitality. According to Muslim tradition, the Prophet Muhammad met the mysterious monk Bahlra in one of these Byzantine monasteries.

“6. One of the most fruitful encounters of Christianity with Arabism took place in northwestern Arabia, in Hijaz, the sphere of indirect Byzantine influence. The federate tribe of 'Udra lived in this region and adopted Christianity quite early in the Byzantine period. Among its many achievements was a special type of poetry, known as 'Udrl or 'Udrite, which was inspired by a special type of love, also called 'Udrn It is practically certain that this type of love and poetry appeared under the influence of Christianity in pre-Islamic times, although it may later have had an Islamic component. It represents the fruitful encounter of the chivalrous attitude toward women in pre-Islamic Arabia and the spiritualization of this attitude through the refining influence of Christianity. Through the Arab Conquests it appeared as amour courtois in western Christendom, whose religion had inspired it in the first instance.”

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Irfan Shahid, Byzantium and the Arabs in the Fifth Century, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library, Washington, D.C. 1989. Beginning with pg. 528. sourcebooks.fordham.edu

pre-Islamic figures from Arabia

Important Arab Figures in Byzantium

Irfan Shahid wrote: “The sources on the Arabs who were important for the Arab-Byzantine relationship in this pre-lslamic period are neither abundant nor detailed enough to make it possible to draw sketches of the more outstanding among them. For the fourth century, it was not possible to recover the features of more than three figures: Imru' al-Qays, the federate king of the Namara inscription; Mavia, the warrior queen of the reign of Valens; and Moses, the eremite who became the bishop of the federates. For the fifth century it is possible to discuss only four of the figures who served both the Byzantine imperium and ecclesi. [Source: Irfan Shahid. Byzantium and the Arabs in the Fifth Century, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library, Washington, D.C. 1989. Beginning with pg. 528, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

“1. Aspebetos/Petrus. The career of this Arab chief was truly remarkable, as he moved through one phase to another. He started as a military commander in the service of the Great King, then became the Byzantine phylarch of the Provincia Arabia, then that of Palaestina Prima, then the bishop of the Palestinian Parembole. The climax of his career was his participation at the Council of Ephesus, where he appears not merely as a subscription in the conciliar list but as an active participant in the debates and a delegate of the Council to Nestorius.

“2. Amorkesos. His is an equally remarkable career, and reminiscent of Aspebetos in that he too had been in the service of the Great King before he defected to Byzantium. But unlike Aspebetos he remained a servant of the imperium, not the ecclesia, although he used the latter in his diplomatic offensive. The former chief in the service of Persia entered a second phase of his life when he became a military power in North Arabia, and a third when he mounted an offensive against the Roman frontier which culminated in his occupation of the island of Iotabe in the Gulf of Eilat. Ecclesiastical diplomacy followed his military achievements and resulted in a visit to Constantinople and royal treatment by Leo. He returned, having concluded a foedus with the emperor, which endowed him with the phylarchate of Palaestina Tertia. What is striking in the success story of this Arab chief is his desire to become a phylarch of the Romans in spite of the power base he had established for himself in the Arabian Peninsula. The lure of the Byzantine connection is nowhere better illustrated than in the career of this chief, who preferred to serve in the Byzantine army than to be an independent king or chief in the Arabian Peninsula. This conclusion, which may be safely drawn from an examination of his career, is relevant to the discussion of the prodosia charge trumped up against the Ghassanid phylarchs of the sixth century. All these Arab chiefs gloried in the Byzantine connection and preferred it to their former Arabian existence.

from pre-Islamic Yemen

“3. Dawud/David. The Salihids were fanatic Christians, and they owe this to the fact that their very existence as federates and dominant federates was related to Christianity — when a monk cured the wife of their eponym, Zokomos, of her sterility and effected the conversion of the chief. His descendants remained loyal to the faith which their ancestor fully embraced, but of all these Dawud is unique in that toward the end of his life his religiosity increased to the point which possibly made him a monk or an ascetic.

“4. Elias. Entirely different in background from all the preceding figures is Elias, the Arab Patriarch of Jerusalem towards the end of the century. While the other three were federate Arabs, Elias was Rhomaic, born in Arabia, either the Provincia in Oriens or the Ptolemaic nome in the limes Aegypti, one of the many Rhomaic Arabs in the service of the imperium or the elesia whose Arab identity has been masked by their assumption of either biblical or Graeco-Roman names.

“These are the four large historical figures in the history of Arab-Byzantine relations in the fifth century. Their careers call for two observations. 1) They were very different from one another: bishop, phylarch, federate king, and patriarch, but all four were involved in both the imperium and the elesia, a reflection of the intimate and inseparable relationship that obtained between the two in the Christian Roman Empire. Three of them were federate Arabs and one was Rhomaic. The four different careers are also a reflection of the wide range of Arab involvement in the life of the empire and of the new opportunities open to them. 2) Their careers reflect the profound metamorphosis that each of them experienced as a result of the Byzantine connection. Perhaps that of Aspebetos is the most remarkable: from a pagan chief to a Byzantine phylarch, to a baptized one, to a bishop of the Parembole, to a participant at the Council of Ephesus and a delegate to Nestorius expressing the strong voice of Arab Orthodoxy. Thus his career represents the highest degree of assimilation that a federate Arab could experience.

Views of Arabs in the A.D. 5th Century

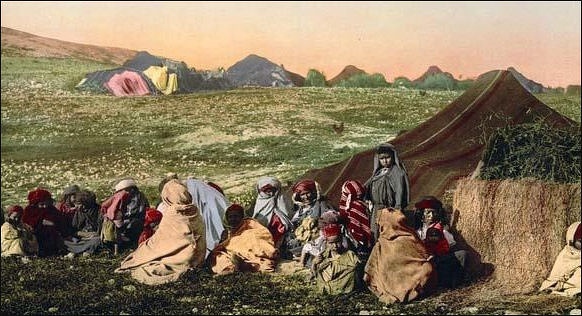

Bedouins in the 19th century

Irfan Shahid wrote: ““Both streams of Byzantine historiography, secular and ecclesiastical, continue to transmit images of the Arabs in the fifth century. Although the negative image of the fourth century is not dead, there is a marked improvement in that image in both streams of fifth-century historiography. [Source: Irfan Shahid. Byzantium and the Arabs in the Fifth Century, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library, Washington, D.C. 1989. Beginning with pg. 528, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

“2. Curatio. In this work, "The Cure of Pagan Maladies," Theodoret projects an image of the Arabs in the context of a pagan world peopled by Greeks and barbarians, and tries to argue for the unity of the human species affirmed by Scripture. He reviews the various peoples and tries to discover their respective virtues. When he comes to the Arabs, he grants them "an intelligence, lively and penetrating . . . and a judgment capable of discerning truth and refuting falsehood."

“The strong affirmative note sounded by Theodoret is supported and fortified by the ecclesiastical documents of the century, especially those of the two ecumenical councils of Ephesus and Chalcedon, in 431 and 451 respectively. The number of Arab bishops, both Rhomaic and federate who participated is remarkable, and they expressed the strong voice of Arab Orthodoxy, first Cyrillian Orthodoxy at Ephesus and then Leonine at Chalcedon. Especially prominent in this expression was Petrus I, the bishop of the Palestinian Parembole, who participated actively at Ephesus and was one of the delegates whom the Council sent to negotiate with Nestorius.

“The two evaluations of the Arabs in Theodoret are striking, coming as they do from a distinguished theologian and church historian, and so is the evidence from the Acta of the two ecumenical councils. But even as the image of the Arabs was being improved by the Greek ecclesiastical writers, it continued to suffer at the hands of a Latin church father.

“1. Jerome, who inherited his image of the Arabs from Eusebius, continued to write about them as unredeemed Ishamelites, a concept from which, as a biblical scholar and exegete, he could not liberate himself. There was another reason behind Jerome's fulminations against the Arabs. He had lived in the monastic community of the desert of Chalcis and later at Bethlehem. Both were subject to Saracen raids that spelt ruin to monasteries, especially at Bethlehem which was actually occupied by the Saracens. Consequently, he fell back on biblical texts which enabled him to refer to these Saracens as servorm et ancillarm nmerus. His older contemporary, St. Augustine, followed in the steps of those who had written on heresies in the East, and naturally the Arabs appear in his De Haeresibs (sec. 83).

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Irfan Shahid, Byzantium and the Arabs in the Fifth Century, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library, Washington, D.C. 1989. Beginning with pg. 528. sourcebooks.fordham.edu

Thi Ain ancient village in Arabia

“2. On the other hand, another Latin author, Rufinus, spoke in complimentary terms of the Arabs in his Ecclesiastical History, as upholders of Orthodoxy. Indeed, he heralded the new generation of ecclesiastical historians in the East — Socrates, Sozomen and Theodoret — who were sympathetic to the world of the barbarians, including the Arabs. But the voice of Rufinus was drowned out by those of the two immensely influential ecclesiastics of the West, Jerome and Augustine, and consequently the image of the Arabs remained dim in the West even before they reached it in the seventh century as conquerors of North Africa and Spain.

As Rufinus opened a new chapter in the history of the image of the Arabs in ecclesiastical historiography, so did Synesius in secular historiography: In one of his letters, written in 404, Synesius praises the courage of the Arabs, soldiers who had been withdrawn most probably from the Ala Tertia Arabum in the limes Aegypti to fight in Pentapolis. In another passage in the same letter he describes the despair of the passengers on the stormtossed ship that was sailing to Pentapolis and lauds the attitude of the Arab soldiers who were prepared to fall on their swords rather than die by drowning. He even grows lyrical and refers to them as "by nature true descendants of Homer."

“3. This bright image in the secular sources was somewhat dimmed later in the century when Malchus of Philadelphia, himself most probably a Rhomaic Arab, wrote and almost neutralized what Synesius had said about the Arabs. In a long and detailed fragment on the emperor Leo in the penultimate year of his reign, Malchus relentlessly criticized the emperor for his relations with the Arab chief Amorkesos, and by implication gave an uncomplimentary picture of the Arabs even though they became foederati of the empire.

“In spite of the negative image that secular and ecclesiastical historiography, represented by Malchus and Jerome projected, the image of the Arabs experienced a marked improvement. Toward the end of the century, in the reign of Anastasius, there arose another group of foederati, who possibly became involved from the beginning in Monophysitism. This completely blackened the image of the' Arabs in the sixth century during which both secular and ecclesiastical historiography combined to project a most uncomplimentary image which damned them as traitors to the imperim and heretics to the eclesia. Thus the fifth century is the golden period in the history of the Arab image, unlike the fourth and the sixth, during which it was tarnished mainly by sharp friction with the central government on doctrinal grounds. The coin of Arab identity looked good on both of its sides. To the imperim the Arabs appeared as faithful guardians of the Roman frontier; to the elesia they appeared as conforming Orthodox believers.”

Arab Self-lmage in the A.D. 5th Century

Irfan Shahid wrote: “The significance of two ecclesiastical historians, Sozomen and Theodoret, is immense for the Byzantine perception of the Arabs in the fifth century. In addition to the improved image that their works provide, they also, especially Theodoret, have preserved data on the Arabs which strongly suggest that the Arabs of this period perceived themselves as descendants of Ishmael. Whether this perception was indigenous among the Arabs or adventitious, having reached them from the Pentateuch either directly through the spread of Judaism in Arabia or mediated through the Christian mission, is not entirely clear. Its reality, however, is clear and certain, and the idiom of Theodoret even suggests that their perception was mixed with pride in the fact of their descent from Ishmael. [Source: Irfan Shahid. Byzantium and the Arabs in the Fifth Century, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library, Washington, D.C. 1989. Beginning with pg. 528, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

“This is the important new element that appears in the fifth century and adds a second mirror to the one that reflects the Byzantine perception of the Arabs. In this new mirror, Ishmael is rehabilitated. He is no longer a figure that embarrasses the Arabs through certain biblical associations but a revered ancestor of whom they are proud. This image became a most important element in Arab religious life in the seventh century, which witnessed an even more complete rehabilitaion of Ishmael. In the Qur’an, Ishmael appears not as the pater eponymous of the Arabs but as the son of the First Patriacrh; Ahraham, and a prophet. The precious passage in the Historia Religiosa of Theodoret proves beyond doubt that the eponymate of Ishmael is rooted in the pre-lslamic Arab past and that it goes back to at least the fifth century.

Sallhids: Fanatic Christian Arabs

Irfan Shahid wrote: “The Salihids were fanatic Christians, and they owe this to the fact that their very existence as federates and dominant federates was related to Christianity — when a monk cured the wife of their eponym, Zokomos, of her sterility and effected the conversion of the chief. His descendants remained loyal to the faith which their ancestor fully embraced, but of all these Dawud is unique in that toward the end of his life his religiosity increased to the point which possibly made him a monk or an ascetic. He built the monastery which carried his name, Dayr Dawud, and he had a court poet from Iyad and a daughter who also was a poetess. The gentleness induced in him by Christianity, apparently was taken advantage of by a coalition of two of the federate tribes, who finally brought about his downfall. His career presents the spectacle of an Arab federate king who loyally served both the imperium and the ecclesia and payed for this service with his life. [Source: Irfan Shahid. Byzantium and the Arabs in the Fifth Century, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library, Washington, D.C. 1989. Beginning with pg. 528, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

The Sallhids endured for almost a century in the service of Byzantium. They represent the golden period in the history of federate-imperial relations. Unlike the Tanukhids and the Ghassanids, the Sallhid doctrinal persuasion was that of the imperial government in Constantinople. Consequently federate-imperial relations were not marred by violent and repeated friction such as vitiated these relations in the fourth and sixth centuries.

“The Salihids fought for Byzantium on the Persian front and distinguished themselves in the two Persian Wars of the reign of Theodosius II. It is also practically certain that they participated in Leo's Vandal Expedition, taking part in the battle of Cape Bon, during which their numbers must have been thinned. This is the most plausible explanation for their ineffectiveness in the defense of the limes Arabic around A.D. 470. Finally, the law of generation and decay which governed the rise and fall of Arab polities before the rise of Islam caught up with them. Powerful Peninsular groups such as the Ghassanids and the Kindites had hewn their way through the Arabian Peninsula and had reached the Roman frontier. The Sallhids, already weakened considerably by their participation in the Vandal War, could not withstand the impact of the combined force of the two new powerful tribal groups. They succumbed in the contest for power and the Ghassanids emerged as the dominant federate group in the sixth century.

“Unlike other federate groups such as the Iyadis, the Salihids remained staunch Christians throughout the Muslim period. This explains why they attained no prominence in Islamic times.

Bedouins in Tunisia in 1899

Arab Tribes in the A.D. 5th Century

Irfan Shahid wrote: “The other tribes of the federate shield took part in the defense of the limes orientalis and in the Persian Wars. They also protected the caravans that moved along the arteries of international trade in north and northwestern Arabia. The Sallhids did not control these tribes as the Ghassanids were to do in the sixth century. The Arabic sources record feuds among these federate tribes. Two of them, Kalb and Namir, united against the dominant group Sallh, brought about the downfall of the Sallhid king Dawud, and must have weakened the power of Sallh, thus contributing ultimately to the victory of the Ghassanids over them and the emergence of a new federate supremacy, the Ghassanid, which controlled most or all of the other tribes of the federate shield in Oriens for almost half a century. [Source: Irfan Shahid. Byzantium and the Arabs in the Fifth Century, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library, Washington, D.C. 1989. Beginning with pg. 528, Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

“In addition to their military role, these federate tribes made some important contributions to Arabic culture in pre-lslamic times. The names of Iyad, Kalb, and 'Udra stand out in connection with the rise of the Arabic script in Oriens in the fifth century and of a new type of love and love poetry, called 'Udrite in Arabic, which represented the confluence of the pre-lslamic chivalrous attitude with Christian ideals of chastity and continence.

“All these federate tribes fought on the side of Byzantium in the period of the Arab Conquests. After the crushing defeat at Yarmuk in 636, they dispersed and their history as foederati came to an end. Some of them emigrated to Anatolia, some stayed on in Oriens, now Arab Bilad al-Sham, and formed part of the Umayyad ajnad system. While the Sallhids remained staunchly Christian, some of the other federate tribes accepted Islam, which enabled them to participate actively in the shaping of Islamic history.

“Before they made their Byzantine connection, these tribes had moved in the restricted and closed orbit of the Arabian Peninsula. In all probability they would have continued to move in that orbit, and history would not have taken notice of them and their achievements. It was the Byzantine connection that drew them into the world of the Mediterranean and gave an international dimension to their history. One of the three constituents of Byantium, Christianity, termmated their isolation and peninsulailsm by making them members of the large world of Christendom and its universal ecclesia.

“Islam was to do what Byzantium had done but in a more substantial way. It made the tribes assume a more active role in shaping the history of the Mediterranean world in both East and West. In the East they formed part of the ajnad, participated in the annual expeditions against the Byzantine heartland, Anatolia, and took part in many sieges of Constantinople. In the West some of them settled on European soil, but their more important role in Spain was cultural.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Irfan Shahid, Byzantium and the Arabs in the Fifth Century, Dumbarton Oaks Research Library, Washington, D.C. 1989. Beginning with pg. 528. sourcebooks.fordham.edu

Bedouin raid

Lack of Historical Research of the Arabian Peninsula

The ancient history and archaeology of the Arabian Peninsula is little known outside a small circle of archaeologists and academics. Donna Abu-Nasra of Associated Press wrote: “Much of the world knows Petra, the ancient ruin in modern-day Jordan that is celebrated in poetry as ,the rose-red city, 'half as old as time,'" and which provided the climactic backdrop for "Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.'' But far fewer know Madain Saleh, a similarly spectacular treasure built by the same civilization, the Nabateans. That's because it's in Saudi Arabia, where conservatives are deeply hostile to pagan, Jewish and Christian sites that predate the founding of Islam in the 7th century. [Source: Donna Abu-Nasra, Associated Press, Sept. 1, 2009 \=]

“Archaeologists are cautioned not to talk about pre-Islamic finds outside scholarly literature. Few ancient treasures are on display, and no Christian or Jewish relics. A 4th or 5th century church in eastern Saudi Arabia has been fenced off ever since its accidental discovery 20 years ago and its exact whereabouts kept secret. \=\

“In the eyes of conservatives, the land where Islam was founded and the Prophet Muhammad was born must remain purely Muslim. Saudi Arabia bans public displays of crosses and churches, and whenever non-Islamic artifacts are excavated, the news must be kept low-key lest hard-liners destroy the finds. "They should be left in the ground," said Sheikh Muhammad al-Nujaimi, a well-known cleric, reflecting the views of many religious leaders. "Any ruins belonging to non-Muslims should not be touched. Leave them in place, the way they have been for thousands of years.'' \=\

“In an interview, he said Christians and Jews might claim discoveries of relics, and that Muslims would be angered if ancient symbols of other religions went on show. "How can crosses be displayed when Islam doesn't recognize that Christ was crucified?'' said al-Nujaimi. "If we display them, it's as if we recognize the crucifixion.''” \=\

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); Encyclopedia of the World Cultures” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994). Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, Al Jazeera, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024