Home | Category: Hittites and Phoenicians

PHOENICIAN RELIGION

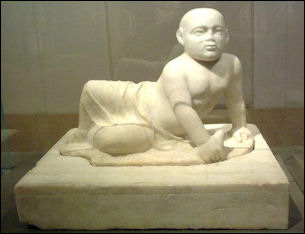

child Votive statue from Eshmun Each Phoenician city had its own set for gods. Tanit was the principal goddess of Carthage. She was known as Ashtoreth in the Bible and Astarte in Byblos and Sidon. The Phoenicians embedded an ankh-like figure called a Tanit in the floors of their homes to ward off evil spirits. Baal Hammon was the main Phoenician god. Other included the goddess Astarte. Sacrifices were made to the god Moloch. Eshmun was the god of healing. Many people were buried in jars. Containers of food and drink, toiletries, cosmetics, lamps, jewelry and ritual objects were buried with the dead.

Eshmoun (one kilometer from Sidon) contains a Phoenician temple complex dedicated to the Phoenician healing god Eshmoun, who, according to legend, was originally a human man who mutilated himself and died in an effort to escape the advances of a goddess, and then was brought back to life by the goddess in the form of a god. Waters from the sacrificial basins at the temple were reported to have miraculous healing powers.

Ugarit texts refer to deities such as El, Asherah, Baak and Dagan, previously known only from the Bible and a handful of other texts. Ugarit literature is full of epic stories about gods and goddesses. This form of religion was revived by the early Hebrew prophets. An 11-inch-high silver-and-gold statuette of a god, circa 1900 B.C., was unearthed at Ugarit in present-day Syria.

Websites PhoeniciaOrg phoenicia.org covers extensive and inclusive Canaanite Phoenician information i.e. the origin, history, geography, religion, arts, thinkers, trade, industry, mythology, language, literature, music, wars, archaeology, and culture of this people. Near East and Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Phoenician Secrets: Exploring the Ancient Mediterranean” by Sanford Holst (2011) Amazon.com;

“Phoenicians: Lebanon's Epic Heritage” by Sanford Holst (2005) Amazon.com;

“Phoenician Civilization: A History from Beginning to End” by History Hourly (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Phoenicians: The Purple Empire of the Ancient World ” by Gerhard Herm (1973) Amazon.com;

“The Phoenicians: Lost Civilizations” by Vadim Jigoulov (2022) Amazon.com;

“In Search of the Phoenicians” by Josephine Quinn (2017) Amazon.com;

"The Phoenicians" by Donald Harden Amazon.com;

"Phoenicians" by Glenn Markoe (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of the Phoenician and Punic Mediterranean” by Carolina López-Ruiz, Brian R. Doak (2019) Amazon.com;

“Carthage Must be Destroyed: The Rise and Fall of an Ancient Mediterranean Civilization” by Richard Miles (2010) Amazon.com;

Comparing Roman and Carthaginian Religions

Comparing Roman and Carthaginian religions, Polybius (c.200-after 118 B.C.) wrote in “History” Book 6: “But among all the useful institutions, that demonstrate the superior excellence of the Roman government, the most considerable perhaps is the opinion which the people are taught to hold concerning the gods: and that, which other men regard as an object of disgrace, appears in my judgment to be the very thing by which this republic chiefly is sustained. I mean, superstition: which is impressed with all it terrors; and influences both the private actions of the citizens, and the public administration also of the state, in a degree that can scarcely be exceeded. [Source: Polybius (c.200-after 118 B.C.), Rome at the End of the Punic Wars “History” Book 6. From: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 166-193

alabaster lion

“This may appear astonishing to many. To me it is evident, that this contrivance was at first adopted for the sake of the multitude. For if it were possible that a state could be composed of wise men only, there would be no need, perhaps, of any such invention. But as the people universally are fickle and inconstant, filled with irregular desires, too precipitate in their passions, and prone to violence; there is no way left to restrain them, but by the dread of things unseen, and by the pageantry of terrifying fiction. The ancients, therefore, acted not absurdedly, nor without good reason, when they inculcated the notions concerning the gods, and the belief of infernal punishments; but much more those of the present age are to be charged with rashness and absurdity, in endeavoring to extirpate these opinions.

“For, not to mention effects that flow from such an institution, if, among the Greeks, for example, a single talent only be entrusted to those who have the management of any of the public money; though they give ten written sureties, with as many seals and twice as many witnesses, they are unable to discharge the trusts reposed in them with integrity. But the Romans, on the other hand, who in the course of their magistracies, and in embassies, disperse the greatest sums, are prevailed on by the single obligation of an oath to perform their duties with inviolable honesty. And as, in other states, a man is rarely found whose hands are pure from public robbery; so, among the Romans, it is no less rare to discover one that is tainted with this crime. But all things are subject to decay and change. This is a truth so evident, and so demonstrated by the perpetual and the necessary force of nature, that it needs no other proof.”

Carthaginian Child Sacrifice

Firstborn sons and daughters were offered by Carthaginian parents as sacrifices in times of grave problems, such as famine, war, drought and plague. The 3rd century Greek writer Kleitatchos wrote: "The Phoenicians, and especially the Carthaginians, when ever they seek to obtain some great favor, vow one of their children, burning it as a sacrifice to a deity to gain success. There stands in their midst a statue of Kronise, its hands extend over a bronze brazier, the flames of which engulfed the child. When the flames fall upon the body, the limbs contract and the open mouth seems almost to be laughing, until the body slips quietly into the brazier."

The ritual was carried out on moonlight nights. Children had their throats slit and were placed into a burning pit before a statue of the god Ba'al Hammon to the sound of music from lyres, tambourines and flutes. The ashes and remain were placed in a special graveyard presided over by the goddess Tanit. Parents were supposed to look on when their children died.

Children were expected to be offered willingly as an offering to Tanit. The rich were expected to offer their children like everyone else but they often purchased substitutes from the poor. If the mother of the substitute cried out at the crucial moment she lost here blood money as well as her child. "While flutes and drums drowned out the wailing, a priest took child from the mother, slit the baby's throat and burned the body. The child's body would then intercede for its people."

More than 20,000 children are believed to have been sacrificed. Dr. David Soren told the New York Times, "There was a peculiar dualism in Carthage in which the trust for commerce, prosperity and the god life were blinded with religion so intense that the richest Carthaginian could cheerfully consign a son or daughter to the flames of the sacrificial pit to redeem a pledge to the gods."

Roman were horrified by Carthaginian infanticide. The were equally appalled by stories of Dido's death and the fact that the commander Hamlar jumped in a fire after losing a battle at Syracuse in 251 B.C.

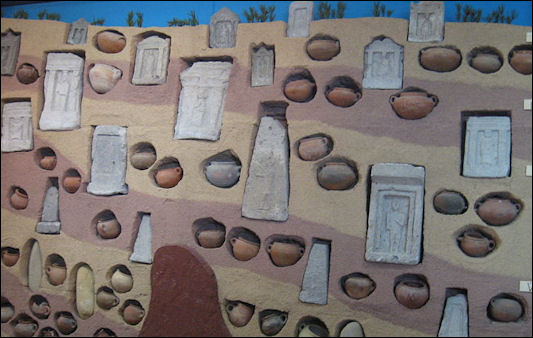

child tombs from Thofet

Reasons for Carthaginian Child Sacrifice

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: The early Christian writer Tertullian writes that when people in Carthage would sacrifice their infants at the Tophet, the mothers would play the ancient equivalent of peek-a-boo with their babies before they were dispatched into the flames as offerings to Baal. These deaths, though achingly poignant, focus on the value of young pristine life and untarnished female sexual purity rather than wealth and power. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, July 14, 2018]

What the focus on vulnerability and female virginity in these stories obscures is that these people were, for all practical purposes, socially and politically powerless. Children were economic assets in the ancient world, but infants could easily die before adulthood. And girls were not as valuable as boys. It is rare (though not completely unheard of) for a military leader to immolate himself for the benefit of the group, and when he did it was for glory, fame, and military conquest. When the truly powerful were sacrificed it was only by proxy: in order to ward off disease the Greeks would sometimes dress a prisoner of war or a pauper as the king and parade him around before throwing him out of the city and (according to some scholars) killing him. But the king himself never actually died; it was just a show.

If the interpretations of these sites are accurate, what these new discoveries show is something sadly obvious. Wherever you are in human history, when it comes to ritual death, it is the vulnerable who are sacrificed for the good of the powerful.

Archaeological Evidence of Carthaginian Infanticide

Tophet is a burial ground near Carthage full of infants and small animals believed to have been used in sacrifice. The charred remains of both animals and children were buried in nearly identical urns with inscriptions of the supreme goddess Tanit or her consort Ba'al Hammon. Many children seem to have been from wealthy families. Some urns contained golden jewelry and painted pottery figurines of Tanit and other deities. On excavated urn read: "To Sire Baal Hammon, Lord of the Sky. I have dedicated Aris, son of Hanna, because you have heard my voice."

Archaeologists believed the children were killed and cremated before their ashes were placed in an urn and buried under a marked tombstone. They believe the children were sacrificed rather than cremated because there are few adults in the cemetery, whereas other Carthaginian cemeteries are mix of children and adults, some cremated, some not.

child tomb Tofet reconstruction

In most societies that practiced some form of human sacrifice, human sacrifice preceded animal sacrifice, but in Carthage the trend seems to have been reversed. In the oldest urns children are buried with animals at a ration of 3 to 1. In younger urns the ratio is 10 children to one animal.

Some scholars believe the stories of Phoenician human sacrifices were made up by the Romans for propaganda purposes. They argue that the charred remains found in the urns are from infants who were stillborn or died of natural causes. And even they did practice human sacrifice there is nothing that unusual about it. According to the prophet Jeremiah the Hebrew were doing the same thing in Jerusalem in the 6th century B.C.

Evidence That Refutes Carthaginian Child Sacrifice

Jarrett A. Lobell wrote Archaeology magazine “A team led by University of Pittsburgh physical anthropologist Jeffrey Schwartz has refuted the long-held claim that the Carthaginians carried out large-scale child sacrifice from the eighth to second centuries B.C. The researchers announced their results this year after spending decades examining the cremated remains of 540 children from 348 burial urns excavated in the Tophet, a cemetery outside Carthage’s main burial ground. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, January/February 2011]

Schwartz determined that about half the children were prenatal or would not have survived more than a few days beyond birth, and the rest died between one month and several years after birth. Only a very few children were between five and six years old, the age at which they begin to be buried in the main cemetery. The mortality rates represented in the cemetery are consistent with prenatal and infant mortality figures found in present-day societies. “There is a credible medically and biologically consistent explanation of the Tophet burials that offers an alternative to sacrifice,” says Schwartz. “While it is possible that the Carthaginians may have occasionally sacrificed humans, as did their contemporaries, the extreme youth of the Tophet burials suggests [the cemetery] was not only for the sacrificed, but also for the unborn and very young, however they died. And since at least 20 percent of them weren’t even born when they were buried, they clearly weren’t sacrificed.”

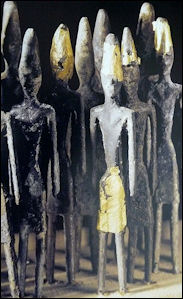

Phoenician statuettes Schwartz also has another type of evidence to support his claim that the Tophet children died of natural causes. “In many societies newborns and very young children are not treated as individuals as older children and adults are,” he says, suggesting that they wouldn’t be considered appropriate for sacrifice. A clue that the Carthaginians didn’t view these children as distinct entities comes from Schwartz’s analysis, which shows that in many urns, there are remains of several different individuals. “There can be four or five of the same right or left cranial bone in the same urn, but there would not be enough other bones to reconstruct the same number of individuals,” says Schwartz. “The remains of multiple children were gathered up, perhaps even from different cremations, and sometimes mixed in with charcoal from the small branches of olive trees used for the funeral pyre.”

Phoenician Life

The Phoenicians had a cult of sacred prostitutes at the shrine of Astatte, goddess of love and war. In Carthage, married couples had their thumbs tied together with leather during their wedding ceremony.

The Phoenicians produced wonderful jewelry such as a gold-mounted scarab with Egyptian designs; an amulet with the Egyptian gods Horus and Anubis; polychrome glass necklaces; golden earrings with hanging baskets and falcons; necklaces with beads and amulets; and bracelets with winged beetles and lutes. Acorns designs have been found on golden necklaces and bracelets. The Phoenicians also created objects designed to be worn in the hair.

The Phoenicians crushed olives with stones to make cooking oil. The first true soap, made of boiled goat fat, water and ash with a lot of potassium carbonate, was developed by the Phoenicians around 600 B.C. Before that Hittites cleaned themselves with the ash of the soapwart plant suspended in water and the Sumerians washed themselves in alkali solutions.

Phoenician Towns and Homes

.jpg) The Phoenicians made their settlements on islands or peninsulas with two harbors on opposite sides, they created artificial pools called “cothns” to provide additional anchorages and places to repair ships. Carthage boasted roofed dry-dock facilities that could accommodate many vessels. The Phoenicians, Persians and Greeks built most of their cities on hilltops. Water came from springs and was often carried in subterranean tunnels.

The Phoenicians made their settlements on islands or peninsulas with two harbors on opposite sides, they created artificial pools called “cothns” to provide additional anchorages and places to repair ships. Carthage boasted roofed dry-dock facilities that could accommodate many vessels. The Phoenicians, Persians and Greeks built most of their cities on hilltops. Water came from springs and was often carried in subterranean tunnels.

Phoenician homes had lead pipes, baths, running hot and cold water and courtyards. Excavations at Carthage give insights into how Phoenician settlements evolved and grew. In the 8th century in one neighborhood the homes were widely space down a dirt track. Later the streets were paved with cobblestones and houses became more closely packed together.

Around 675 B.C. there was a large influx of Phoenicians throughout the Mediterranean and they carried with them four-room houses typical of the Levant. This period of migration coincided with Assyrian aggression in the Levant. When Carthage reached its peak, houses were built over hearths. A layer of black covers the whole city is the result of the fires that destroyed Carthage in 146 B.C.

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: Thanks to the advent of cultural resource management and rescue archaeology, over the past few decades archaeologists have been able to conduct excavations and gain a better understanding of what Phoenician settlements were like, especially in Iberia. They were almost always located on small coastal promontories, peninsulas, or islands with good natural anchorages and river access to inland resources. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, May/June 2016]

The two major determining factors of a settlement's location seemed to be an availability of trade with local Iberian communities and proximity to prominent shipping routes. However, these settlements were more than just simple trading posts inhabited by Phoenician merchants. They became complex communities that farmed the surrounding fields, manufactured their own products, excelled in metallurgy, had organized urban plans, and were home to diverse populations. "They were not just merchants who stuck it out for a few years to earn a fortune and then go back home," says van Dommelen. "The evidence [suggests] fully developed communities with elites, commoners, craftsmen, women, children, and slaves, among others."

Phoenician Culture

The Phoenicians served as cultural middlemen. In many ways the helped spread Assyrian and Mesopotamia culture in general around the Mediterranean Sea where there ideas were picked up by the Greeks and Romans and other groups. Their main contribution was an alphabet.

The Phoenicians are said to have had a rich literature but nothing of it remains. Phoenicians played zithers and also believed to have had a rich tradition of music. Some Phoenician and Etruscans texts have been found on papyrus sheets concealed in the ruins of a temple sacked sacked by Romans.

Phoenician art was influenced by the art of ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia and Greece. Phoenician treasures includes a 4th century B.C. mosaic of leopard attacking a bull; an ivory relief of a lion mauling an Ethiopian, decorated with gold, lapis lazuli and carnelian; exquisite small glass bowls with rich turquoise color derived from calcium and sodium in Phoenician sands; and sculptures with Roman, Egyptian and far Eastern features.

Phoenician Art

The Phoenicians made beautiful floor mosaics with pieces of limestone, shell, glass and colored stones and sculptures with a variety of materials. They produced stunning bronze figures, lovely jewelry, and funerary urns decorated with stick figures of gods. They worked bronze, iron, glass and gold; dyed cloth with purple dye; and produced silver bowls, painted ostrich eggs, gold and glass jewelry, gilt bronze breastplates, mirrors, razors, and terra-cotta figures.

The Phoenicians made beautiful floor mosaics with pieces of limestone, shell, glass and colored stones and sculptures with a variety of materials. They produced stunning bronze figures, lovely jewelry, and funerary urns decorated with stick figures of gods. They worked bronze, iron, glass and gold; dyed cloth with purple dye; and produced silver bowls, painted ostrich eggs, gold and glass jewelry, gilt bronze breastplates, mirrors, razors, and terra-cotta figures.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Phoenician artisans were skilled in wood, ivory, and metalworking, as well as textile production. In the Old Testament (2 Chron.), the master craftsman Hiram of Tyre was commissioned to build and embellish the temple of Solomon in Jerusalem. Homer's Iliad describes a prize at the funeral games of Patroklos as a mixing bowl of chased silver—"a masterpiece of Sidonian craftsmanship" (Book 13). It also mentions that the embroidered robes of Priam's wife, Hecabe, were "the work of Sidonian women" (Book 6). Phoenician art is in fact an amalgam of many different cultural elements—Aegean, northern Syrian, Cypriot, Assyrian, and Egyptian. The Egyptian influence is often especially prominent in the art but was constantly evolving as the political and economic relations between Egypt and the Phoenician cities fluctuated. Perhaps the most significant contribution of the Phoenicians was an alphabetic writing system that became the root of the Western alphabets when the Greeks adopted it. [Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004]

The world’s oldest terra cotta mosaics, dated to the 5th century B.C., were excavated from Carthage. Terra-cotta characters — which were almost life-size and bore exaggerated expressions like those on Greek drama masks — were buried with the dead in the 6th century B.C. and were there perhaps to protect the dead from evil spirits. The Phoenicians also produced silver coins with portraits of Hannibal and other celebrities.

Art with human or divine images included slender bronze figures covered by gold leaf skins made as an offering at the temple in Byblos; a 15-inch-high statue with an Egyptian headdress from the 13th century B.C.; sarcophagi with both Greek and Egyptian elements; and ivory plaques honoring the sacred prostitutes of Astare. Little Phoenician art remain because so much of it was destroyed by the Romans.

Mariusz Gwiazda, from the Polish Center of Mediterranean Archaeology, which is working in the ancient Phoenician town of Porphyreon in present-day Lebanon, told Archaeology magazine: Phoenician objects incorporate a combination of Greek, Phoenician, and Egyptian traits. “From the beginning, Phoenician art borrows different ideas from different cultures,” says Gwiazda, “mixing them together and creating its own hybrid material language.” He believes the pieces were meant to depict deities, though in the absence of written evidence it is difficult to say which ones. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, September-October 2017]

Phoenician Masks

A Phoenician Mask clay mold dated to 10th–9th century B.C. and measuring 8.3 x 6.7 x 2.6 inches, was found in Tel Achziv, Israel. According to Archaeology magazine: “For many ancient Mediterranean cultures, there are particular types of artifacts with which they are most closely associated — for the Mycenaeans, it is tablets written in Linear B, for the Greeks it might be marble sculptures, and for the Romans, it may be the amphoras that transported Roman olive oil, wine, and fish sauce across the empire. For the Phoenicians, who inhabited the eastern Mediterranean in the second and first millennia B.C., perhaps the most characteristic artifacts are clay masks. Although these masks have been found from Phoenicia all the way to Spain, this is the first time a mold used to make such a mask has been discovered. “The artifact is exceptional because there are no other known clay molds of anthropomorphic masks, it was found in a sealed context, and it’s almost complete,” says archaeologist Michael Jasmin of the French National Center for Scientific Research. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2017]

“Despite their ubiquity, however, and unlike tablets or sculptures or amphoras, the function of these masks is not so evident. The Tel Achziv mask mold was found with pottery bowls, chalices, and goblets in an assemblage that, says Jasmin, would likely have been part of a religious or mortuary ritual. “It may have been used during a funeral, then placed in a tomb with the deceased to retain a ‘face’ in the afterlife,” says Jasmin. “We don’t think it represents a specific person, but rather a generalized portrait of a young Phoenician man with distinctive local, ethnic physical traits. Even though facial details such as beards were painted on, these masks don’t seem to represent real people.”

Phoenician Dogs

Malta pharaoh hound At the coastal city of Ashkelon in present-day Israel archeologist excavated a dog cemetery dated ot the early 5th century B.C. with thousands of dogs carefully arranged suggesting reverence bordering on worship. Brian Hesse, an archeologist at the site, told National Geographic, “the dogs apparently died naturally. They show no trauma or cut marks from being butchered, They were carefully laid on their sides in a shallow pit with their tails wrapped around their hind legs.”

By some calculations the Ashkelon cemetery is the oldest known dog cemetery. Dating back to 500 B.C. when the region was occupied by a Persian kingdom, the cemetery contains thousands of animals, which may have been worshiped as part of a Phoenician healing cult. Each dog — from puppies to elderly adults — was carefully placed on its side in a shallow pit, legs flexed. [National Geographic Geographica, November 1991]

The dogs were only buried like this for a brief period and thought to have been part of short-lived dog cult. Many theories abound as to why the dogs were treated with such reverence. Harvard archeologist Lawrence Stager told National Geographic: "The dogs were obviously quite important...or they would not have bothered to treat them with such care.” Harvard archeologist Larry Stage told National Geographic . “Dogs were associated with healing in many cultures because they lick their sores and wounds.”

Phoenician Elephants

Elephants were native to North Africa in Phoenician times. There were elephant farms to produce animals for work and ivory for craftsman. Elephants were introduced into warfare after Alexander the Great and his men encountered them in India. They were part of Carthage’s armies from the third century B.C. onwards.

Elephants buried in elaborate tombs, dated to 3500 B.C., were found in cemetery in Hierakonpolisin ancient Egypt. One of the elephant was ten to eleven years old. That is the age when young males are expelled from the herd. Young and inexperienced, they can be captured and trained at that age.

African elephants were used by Hannibal of Carthage. Forest African elephants have been used in Gangla and Bodio, near Garmaba national park in the eastern part of former Zaire, since the turn of the century.

Hannibal coin It had long been thought that Asian but north African elephants could be tamed. Experiments in Zimbabwe, South Africa and Botswana have showed that African elephants can be tamed. The tame elephants are trained when they are young. They are orphans whose mother was skilled by poachers. They are often very attached t their human caretakers. Park rangers in Zimbabwe ride elephants on anti-poaching patrols. They have plans to use the animals to plow rocky, hard fields that other animals can't tackle.

Some circus elephants are African elephants. In Botswana a guide has trained a former circus-elephants to take tourists on safari as Indian elephants in India and Nepal do. "Upon command," writes Gail Phares who went on a safari on an African elephant, "the elephants got down on the knees and a staff member provided his knee for us to step on as we climbed up on top of the elephant and into the howdah (box saddle). The mahout then alerted us when the elephant was about to get up. We hung on to the sides of the howdah as we tipped backward and then lurched forward. It is not dangerous or frightening as along as you are prepared when the mahout gives the order...During 3- to 4- morning and afternoon game drives we tried several positions to give our leg and muscles a change. We sat with legs in front of us or with one leg out on each side under the frame or with our legs crossed under us. There was a small compartment behind.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, the BBC and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024