Home | Category: Hittites and Phoenicians

CARTHAGE

Carthage (10 miles north of modern Tunis in Tunisia) was once the greatest city in the world. It was the home of Hannibal, who threatened Rome with his elephants and huge armies, and was the center of a great Phoenician trading empire that extended across North Africa and the Mediterranean. The period when Carthage was the dominate power in the ancient world is called the Punic Era. Little more than foundations and walls remain of the great city today.

Carthage (10 miles north of modern Tunis in Tunisia) was once the greatest city in the world. It was the home of Hannibal, who threatened Rome with his elephants and huge armies, and was the center of a great Phoenician trading empire that extended across North Africa and the Mediterranean. The period when Carthage was the dominate power in the ancient world is called the Punic Era. Little more than foundations and walls remain of the great city today.

Carthage has also been portrayed as one of the world’s most decadent cities. In his novel “Salambo” , Flaubert depicted Carthage as a city of unimaginable wealth and indescribable debauchery and violence, in addition to romanticizing Hannibal and his elephants. This apect of Carthage’s reputation is at least partly due to the fact that most of what we know about it is based accounts by its enemies, Greece and Rome.

In 814 B.C., the Phoenician city state of Tyre founded Carthage — Qart-hadasht or “new city” — in northern Africa. Today, Carthage is an affluent neighborhood of Tunis in Tunisia. It emerged as powerful city state when Tyre was sacked by the Babylonians in 6th century B.C. Today, ancient Carthage is a modern, wealthy suburb of Tunis.

Plutarch called the Carthaginians a "course and gloomy people." Appian describe them as "cruel and arrogant." The Greek historian Plybius wrote in the 2nd century B.C. they " were far superior, both in the speed of their ships and they way they built them, and also in the experience and skill of their seamen.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

PUNIC WARS AND HANNIBAL africame.factsanddetails.com ;

FIRST PUNIC WAR (218-201 B.C.): ROME AND CARTHAGE BATTLE IN THE MEDITERRANEAN AND SICILY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

SECOND PUNIC WAR (218-201 B.C.): CARTHAGE SUCCESSES, ULTIMATE ROMAN VICTORY europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HANNIBAL: HIS LIFE, ACHIEVEMENTS AGAINST ROME, EXILE, DEATH europe.factsanddetails.com ;

HANNIBAL CROSSES THE ALPS: ELEPHANTS, POSSIBLE ROUTES AND HOW HE DID IT europe.factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY CARTHAGE VICTORIES IN THE SECOND PUNIC WAR (218-201 B.C.) europe.factsanddetails.com ;

THIRD PUNIC WAR: ROME DECISIVELY DEFEATS CARTHAGE europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Oxford Handbook of the Phoenician and Punic Mediterranean” by Carolina López-Ruiz, Brian R. Doak (2019) Amazon.com;

“Carthage Must be Destroyed: The Rise and Fall of an Ancient Mediterranean Civilization” by Richard Miles (2010) Amazon.com;

“Phoenician Secrets: Exploring the Ancient Mediterranean” by Sanford Holst (2011) Amazon.com;

“Phoenicians: Lebanon's Epic Heritage” by Sanford Holst (2005) Amazon.com;

“Phoenician Civilization: A History from Beginning to End” by History Hourly (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Phoenicians: The Purple Empire of the Ancient World ” by Gerhard Herm (1973) Amazon.com;

“The Phoenicians: Lost Civilizations” by Vadim Jigoulov (2022) Amazon.com;

“In Search of the Phoenicians” by Josephine Quinn (2017) Amazon.com;

"The Phoenicians" by Donald Harden Amazon.com;

"Phoenicians" by Glenn Markoe (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000) Amazon.com;

Founding of Carthage

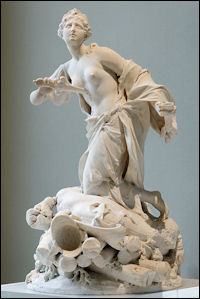

Death of Dido Carthage was founded near the narrowest straits between Africa and Europe in 846 B.C. by the Phoenicians as a way station for trade between its main cities in present-day Lebanon and its colonies. According to legend it was founded in 814 B.C. by Elisa, the Princess of Tyre, who fled with to escape from her brother, King Pygmalion of the Phoenicians, who had murdered her husband.

Elisa was Virgil's Dido in the “Aeneid” and Jezebel's grandniece. She arrived first in Cyprus, where she rescued 80 virgins from ritual prostitution at a temple, and arrived in Tunisia with a chalice of gold and a group noblemen and founded Carthage on a harbor near an easy-to-defend promontory strategically located at the narrowest stretch of the Mediterranean Sea between Sicily and North Africa.

Carthage was originally called Byrsa, meaning “Oxhide.” According to legend Elisa was allowed it to claim as much land as she cover with animal hide. To claim as much land as possible she cut an oxhide into very thin strips and tied them end to end and encircled an entire coastal hill. According to Virgil, Dido stabbed herself and leapt into a pyre of flames after her lover Aeneas left for Rome

Carthage as a Great City

Carthage grew in importance after the Phoenician cities on the Syrian-Lebanon coast lost their independence in the 6th century B.C. At its height in the 3rd and 4th centuries B.C. the empire of Carthage covered much of North Africa and extended into Spain, Sicily and Sardinia. At its height the city of Carthage was home to perhaps a half million people and spacious six-story dwellings, mosaic floors, gardens, formidable walls, rich surrounding farmlands and a circular naval base with drydocks, covered slips and 200 war triremes.

Carthage brought the ideas and civilization which the Phoenicians had developed in the East into the western Mediterranean. Her power was based upon trade and commercial supremacy. She had brought under her control the trading colonies of northern Africa and many of the Greek cities of Sicily. She was, in fact, the great merchant of the Mediterranean. She had grown wealthy and strong by buying and selling the products of the East and the West—the purple of Tyre, the frankincense of Arabia, the linen of Egypt, the gold of Spain, the silver of the Balearic Isles, the tin of Britain, and the iron of Elba. She had formed commercial treaties with the chief countries of the world. She coveted not only the Greek cities of Sicily, but the Greek cities of Italy as well. We can thus see how Rome and Carthage became rivals for the possession of the countries bordering upon the western Mediterranean Sea. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901), forumromanum.org \~]

Carthage brought the ideas and civilization which the Phoenicians had developed in the East into the western Mediterranean. Her power was based upon trade and commercial supremacy. She had brought under her control the trading colonies of northern Africa and many of the Greek cities of Sicily. She was, in fact, the great merchant of the Mediterranean. She had grown wealthy and strong by buying and selling the products of the East and the West—the purple of Tyre, the frankincense of Arabia, the linen of Egypt, the gold of Spain, the silver of the Balearic Isles, the tin of Britain, and the iron of Elba. She had formed commercial treaties with the chief countries of the world. She coveted not only the Greek cities of Sicily, but the Greek cities of Italy as well. We can thus see how Rome and Carthage became rivals for the possession of the countries bordering upon the western Mediterranean Sea. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901), forumromanum.org \~]

The Greek historian Diodorus wrote: "the villas were full of everything that contributes to the pleasures of life...The land was cultivated partly as vineyards and partly as olive groves, and also was abounding in other fruit trees. In the remaining area, herds of cattle and flocks of sheep grazed, and the neighboring pastures were full of grazing horses." According to Strabo, Carthage at it peak had a population of 800,000. But even allowing for exaggeration it had at least 100,000, many of them former slaves and Berber nomads who migrated to the city. Some scholars believe the huge urban migration to Carthage was so large it might have left Carthage short of food.

Elephants in Carthage

Elephants were native to North Africa in Phoenician times. There were elephant farms to produce animals for work and ivory for craftsman. Elephants were introduced into warfare after Alexander the Great and his men encountered them in India. They were part of Carthage’s armies from the third century B.C. onwards.

Elephants buried in elaborate tombs, dated to 3500 B.C., were found in cemetery in Hierakonpolisin ancient Egypt. One of the elephant was ten to eleven years old. That is the age when young males are expelled from the herd. Young and inexperienced, they can be captured and trained at that age.

African elephants were used by Hannibal of Carthage. Forest African elephants have been used in Gangla and Bodio, near Garmaba national park in the eastern part of former Zaire, since the turn of the century.

Hannibal It had long been thought that Asian but north African elephants could be tamed. Experiments in Zimbabwe, South Africa and Botswana have showed that African elephants can be tamed. The tame elephants are trained when they are young. They are orphans whose mother was skilled by poachers. They are often very attached t their human caretakers. Park rangers in Zimbabwe ride elephants on anti-poaching patrols. They have plans to use the animals to plow rocky, hard fields that other animals can't tackle.

Some circus elephants are African elephants. In Botswana a guide has trained a former circus-elephants to take tourists on safari as Indian elephants in India and Nepal do. "Upon command," writes Gail Phares who went on a safari on an African elephant, "the elephants got down on the knees and a staff member provided his knee for us to step on as we climbed up on top of the elephant and into the howdah (box saddle). The mahout then alerted us when the elephant was about to get up. We hung on to the sides of the howdah as we tipped backward and then lurched forward. It is not dangerous or frightening as along as you are prepared when the mahout gives the order...During 3- to 4- morning and afternoon game drives we tried several positions to give our leg and muscles a change. We sat with legs in front of us or with one leg out on each side under the frame or with our legs crossed under us. There was a small compartment behind.”

Carthage Government

Polybius (c.200-after 118 B.C.) wrote in “Rome at the End of the Punic Wars: “The government of Carthage seems also to have been originally well contrived with regard to those general forms that have been mentioned. For there were kings in this government, together with a senate, which was vested with aristocratic authority. The people likewise enjoy the exercise of certain powers that were appropriated to them. In a word, the entire frame of the republic very much resembled those of Rome and Sparta. But at the time of the war of Hannibal the Carthaginian constitution was worse in its condition than the Roman. For as nature has assigned to every body, every government, and every action, three successive periods; the first, of growth; the second, of perfection; and that which follows, of decay; and as the period of perfection is the time in which they severally display their greatest strength; from hence arose the difference that was then found between the two republics. [Source: Polybius “Rome at the End of the Punic Wars”: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 166-193]

Hannibal “For the government of Carthage, having reached the highest point of vigor and perfection much sooner than that of Rome, had now declined from it in the same proportion: whereas the Romans, at this very time, had just raised their constitution to the most flourishing and perfect state. The effect of this difference was, that among the Carthaginians the people possessed the greatest sway in all deliberations, but the senate among the Romans. And as, in the one republic, all measures were determined by the multitude; and, in the other, by the most eminent citizens; of so great force was this advantage in the conduct of affairs, that the Romans, though brought by repeated losses into the greatest danger, became, through the wisdom of their counsels, superior to the Carthaginians in the war.”

The historian Oliver J. Thatcher wrote: “Rome, with the end of the third Punic war, 146 B. C., had completely conquered the last of the civilized world. The best authority for this period of her history is Polybius. He was born in Arcadia, in 204 B. C., and died in 122 B. C. Polybius was an officer of the Achaean League, which sought by federating the Peloponnesus to make it strong enough to keep its independence against the Romans, but Rome was already too strong to be resisted, and arresting a thousand of the most influential members, sent them to Italy to await trial for conspiracy. Polybius had the good fortune, during seventeen years exile, to be allowed to live with the Scipios. He was present at the destructions of Carthage and Corinth, in 146 B. C., and did more than anyone else to get the Greeks to accept the inevitable Roman rule. Polybius is the most reliable, but not the most brilliant, of ancient historians.”

Rome Verus Carthage

In comparing these two great rivals of the West, we might say that they were nearly equal in strength and resources. Carthage had greater wealth, but Rome had a better organization. Carthage had a more powerful navy, but Rome had a more efficient army. Carthage had more brilliant leaders, while Rome had a more steadfast body of citizens. The main strength of Carthage rested in her wealth and commercial resources, while that of Rome depended upon the character of her people and her well-organized political system. The greatness of the Carthaginians was shown in their successes, while the greatness of the Romans was most fully revealed in the dark hours of disaster and trial. [Source: “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901), forumromanum.org \~]

When Carthage came into conflict with Rome, it had in some respects the same kind of government as the Roman republic. It had two chief magistrates (called suffetes), corresponding to the Roman consuls. It had a council of elders, called the “hundred,” which we might compare to the Roman senate. It had also an assembly something like the Roman comitia. But while the Carthaginian government had some outward similarity to the Roman, it was in its spirit very different. The real power was exercised by a few wealthy and prominent families. The Carthaginians, moreover, did not understand the Roman method of incorporating their subjects into the state; and hence did not possess a great body of loyal citizens, as did Rome. But one great advantage of the Carthaginian government was the fact that it placed the command of the army in the hands of a permanent able leader, and not in the hands of its civil magistrates, who were constantly changing as were the consuls at Rome.

Polybius wrote in “History” Book 6: “If we descend to a more particular comparison, we shall find, that with respect to military science, for example, the Carthaginians, in the management and conduct of a naval war, are more skillful than the Romans. For the Carthaginians have derived this knowledge from their ancestors through a long course of ages; and are more exercised in maritime affairs than any other people. But the Romans, on the other hand, are far superior in all things that belong to the establishment and discipline of armies. For this discipline, which is regarded by them as the chief and constant object of their care, is utterly neglected by the Carthaginians; except only that they bestow some little attention upon their cavalry. The reason of this difference is, that the Carthaginians employ foreign mercenaries; and that on the contrary the Roman armies are composed of citizens, and of the people of the country. Now in this respect the government of Rome is greatly preferable to that of Carthage. For while the Carthaginians entrust the preservation of their liberty to the care of venal troops; the Romans place all their confidence in their own bravery, and in the assistance of their allies. From hence it happens, that the Romans, though at first defeated, are always able to renew the war; and that the Carthaginian armies never are repaired without great difficulty. Add to this, that the Romans, fighting for their country and their children, never suffer their ardor to be slackened; but persist with the same steady spirit till they become superior to their enemies. From hence it happens, likewise, that even in actions upon the sea, the Romans, though inferior to the Carthaginians, as we have already observed, in naval knowledge and experience, very frequently obtain success through the mere bravery of their forces. For though in all such contests a skill in maritime affairs must be allowed to be of the greatest use; yet, on the other hand, the valor of the troops that are engaged is no less effectual to draw the victory to their side. [Source: Polybius (c.200-after 118 B.C.), Rome at the End of the Punic Wars “History” Book 6. From: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 166-193

“In things that regard the acquisition of wealth, the manners also, and the customs of the Romans, are greatly preferable to those of the Carthaginians. Among the latter, nothing is reputed infamous, that is joined with gain. But among the former, nothing is held more base than to be corrupted by gifts, or to covet an increase of wealth by means that are unjust. For as much as they esteem the possession of honest riches to be fair and honorable, so much, on the other hand, all those that are amassed by unlawful arts, are viewed by them with horror and reproach. The truth of this fact is clearly seen in the following instance. Among the Carthaginians, money is openly employed to obtain the dignities of the state: but all such proceeding is a capital crime in Rome. As the rewards, therefore, that are proposed to virtue in the two republics are so different, it cannot but happen, that the attention of the citizens to form their minds to virtuous actions must be also different.”

Roman and Carthaginian People and Culture Compared

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: ““Although there must have been Carthaginian histories, they all perished completely (a phenomenon perhaps connected with the Roman insistence upon stamping out every last vestige of Carthaginian life, in 146 B.C.). Of poetry and other literature we have nothing. Oddly, given the importance of wealth in the state, the Carthaginians were slow to begin coining money (around 410). Moderns have for the most part tended to share the cultural stereotypes of the Carthaginians held by the Greeks and Romans in antiquity. For all that Carthage was wealthy and well governed, the Greeks and Romans viewed them as bejeweled, perfumed, effeminate, sybaritic easterners. Nor has it helped their reputation to have it confirmed, by the excavations on the site of Carthage itself, that the Carthaginians routinely performed human sacrifice; not only do inscriptions mention it, but numerous urns containing the burnt bones of sacrificial victims (some animal, some human) have been found. In times of crisis the gods would get the choicest sacrificial victim of all: human babies. In 310, after a disastrous defeat at the hands of Agathocles, the Carthaginians are supposed to have sacrificed 500 babies to Baal.” [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

Polybius wrote in “History” Book 6: “Now the people of Italy are by nature superior to the Carthaginians and the Africans, both in bodily strength, and in courage. Add to this, that they have among them certain institutions by which the young men are greatly animated to perform acts of bravery. It will be sufficient to mention one of these, as a proof of the attention that is shown by the Roman government, to infuse such a spirit into the citizens as shall lead them to encounter every kind of danger for the sake of obtaining reputation in their country. When any illustrious person dies, he is carried in procession with the rest of the funeral pomp, to the rostra in the forum; sometimes placed conspicuous in an upright posture; and sometimes, though less frequently, reclined. And while the people are all standing round, his son, if he has left one of sufficient age, and who is then at Rome, or, if otherwise, some person of his kindred, ascends the rostra, and extols the virtues of the deceased, and the great deeds that were performed by him in his life. By this discourse, which recalls his past actions to remembrance, and places them in open view before all the multitude, not those alone who were sharers in his victories, but even the rest who bore no part in his exploits, are moved to such sympathy of sorrow, that the accident seems rather to be a public misfortune, than a private loss. He is then buried with the usual rites; and afterwards an image, which both in features and complexion expresses an exact resemblance of his face, is set up in the most conspicuous part of the house, inclosed in a shrine of wood. Upon solemn festivals, these images are uncovered, and adorned with the greatest care. [Source: Polybius (c.200-after 118 B.C.), Rome at the End of the Punic Wars, “History” Book 6. From: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 166-193

“And when any other person of the same family dies, they are carried also in the funeral procession, with a body added to the bust, that the representation may be just, even with regard to size. They are dressed likewise in the habits that belong to the ranks which they severally filled when they were alive. If they were consuls or praetors, in a gown bordered with purple: if censors, in a purple robe: and if they triumphed, or obtained any similar honor, in a vest embroidered with gold. Thus appeared, they are drawn along in chariots preceded by the rods and axes, and other ensigns of their former dignity. And when they arrive at the forum, they are all seated upon chairs of ivory; and there exhibit the noblest objects that can be offered to youthful mind, warmed with the love of virtue and of glory. For who can behold without emotion the forms of so many illustrious men, thus living, as it were, and breathing together in his presence? Or what spectacle can be conceived more great and striking? The person also that is appointed to harangue, when he has exhausted all the praises of the deceased, turns his discourse to the rest, whose images are before him; and, beginning with the most ancient of them, recounts the fortunes and the exploits of every one in turn. By this method, which renews continually the remembrance of men celebrated for their virtue, the fame of every great and noble action become immortal. And the glory of those, by whose services their country has been benefited, is rendered familiar to the people, and delivered down to future times. But the chief advantage is, that by the hope of obtaining this honorable fame, which is reserved for virtue, the young men are animated to sustain all danger, in the cause of the common safety. For from hence it has happened, that many among the Romans have voluntarily engaged in single combat, in order to decide the fortune of an entire war. Many also have devoted themselves to inevitable death; some of them in battle, to save the lives of other citizens; and some in time of peace to rescue the whole state from destruction. Others again, who have been invested with the highest dignities have, in defiance of all law and customs, condemned their own sons to die; showing greater regard to the advantage of their country, than to the bonds of nature, and the closest ties of kindred.

Dido

“Very frequent are the examples of this kind, that are recorded in the Roman story. I shall here mention one, as a signal instance, and proof of the truth of all that I have affirmed. Horatius, surnamed Cocles, being engaged in combat with two enemies, at the farthest extremity of the bridge that led into Rome across the Tiber, and perceiving that many others were advancing fast to their assistance, was apprehensive that they would force their way together into the city. turning himself, therefore, to his companions that were behind him, he called to them aloud, that should immediately retire and break the bridge. While they were employed in this work, Horatius, covered over with wounds, still maintained the post, and stopped the progress of the enemy; who were struck with his firmness and intrepid courage, even more than with the strength of his resistance. And when the bridge was broken, and the city secured from insult, he threw himself into the river with his armor, and there lost his life as he had designed: having preferred the safety of his country, and the future fame that was sure to follow such an action, to his own present existence, and to the time that remained for him to live. Such is the spirit, and such the emulation of achieving glorious action, which the Roman institutions are fitted to infuse into the minds of youth.

Roman and Carthaginian Religions Compared

Polybius (c.200-after 118 B.C.) wrote in “History” Book 6: “But among all the useful institutions, that demonstrate the superior excellence of the Roman government, the most considerable perhaps is the opinion which the people are taught to hold concerning the gods: and that, which other men regard as an object of disgrace, appears in my judgment to be the very thing by which this republic chiefly is sustained. I mean, superstition: which is impressed with all it terrors; and influences both the private actions of the citizens, and the public administration also of the state, in a degree that can scarcely be exceeded. [Source: Polybius (c.200-after 118 B.C.), Rome at the End of the Punic Wars “History” Book 6. From: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 166-193

“This may appear astonishing to many. To me it is evident, that this contrivance was at first adopted for the sake of the multitude. For if it were possible that a state could be composed of wise men only, there would be no need, perhaps, of any such invention. But as the people universally are fickle and inconstant, filled with irregular desires, too precipitate in their passions, and prone to violence; there is no way left to restrain them, but by the dread of things unseen, and by the pageantry of terrifying fiction. The ancients, therefore, acted not absurdedly, nor without good reason, when they inculcated the notions concerning the gods, and the belief of infernal punishments; but much more those of the present age are to be charged with rashness and absurdity, in endeavoring to extirpate these opinions.

“For, not to mention effects that flow from such an institution, if, among the Greeks, for example, a single talent only be entrusted to those who have the management of any of the public money; though they give ten written sureties, with as many seals and twice as many witnesses, they are unable to discharge the trusts reposed in them with integrity. But the Romans, on the other hand, who in the course of their magistracies, and in embassies, disperse the greatest sums, are prevailed on by the single obligation of an oath to perform their duties with inviolable honesty. And as, in other states, a man is rarely found whose hands are pure from public robbery; so, among the Romans, it is no less rare to discover one that is tainted with this crime. But all things are subject to decay and change. This is a truth so evident, and so demonstrated by the perpetual and the necessary force of nature, that it needs no other proof.”

Punic sarcoghages

Carthaginian Law of Sacrifices, c. 400 B.C.

The historian George A. Barton wrote in 1920: “The Carthaginians, from whom this document comes, were an offshoot of the Phoenicians, who were, in turn, descended from the Canaanites. They were accordingly of kindred race to the Hebrews. One can, therefore, see from this document something of how the Levitical institutions of Israel resembled and how they differed from those of their kinsmen. It will be seen that the main sacrifices bore the same names among both peoples. The Carthaginians, though, has no "sin-offering," while among the Hebrews we find no "prayer-offering." The ways of rewarding the priests also differed among the two peoples. The Hebrews had no such regular tariff of priests= dues as the Carthaginians, but parts of certain offerings and all of others belonged to them.” [Source: George A. Barton, “Archaeology and the Bible”,” 3rd Ed., (Philadelphia: American Sunday-School Union, 1920), pp. 342-343.

The Carthaginian Law of Sacrifices, c. 400 B.C. reads: “Temple of Baalzephon. Tariff of dues, which the superintendents of dues fixed in the time of our rulers, Khalasbaal, the judge, son of Bodtanith, son of Bodeshmun, and of Khalasbaal, the judge, son of Bodeshmun, son of Khalasbaal, and their colleagues.

For an ox as a whole burnt-offering or a prayer-offering, or a whole peace-offering, the priests shall have 10 (shekels) of silver for each, and in case of a whole burnt-offering, they shall have in addition to this fee 300 shekels of flesh and, in case of a prayer-offering, the trimmings, the joints; but the skin and the fat of the inwards and the feet and the rest of the flesh the owner of the sacrifice shall have.

For a calf whose horns are wanting, in case of one not castrated, or in case of a ram as a whole burnt-offering, the priests shall have 5 shekels of silver for each; and in case of a whole burnt-offering they shall have in addition to this fee 150 shekels of flesh, and, in case of a prayer-offering, the trimmings and the joints but the skin and the fat of the inwards and the feet and the rest of the flesh the owner of the sacrifice shall have.

In case of a ram or a goat as a whole burnt-offering, or a prayer-offering, or a whole peace-offering, the priests shall have 1 shekel of silver and 2 zars for each, and, in case of a prayer-offering, they shall have in addition to this fee the trimmings and the joints; but the skin and the fat of the inwards and the feet and the rest of the flesh the owner of the sacrifice shall have.

For a lamb, or a kid, or the young of a hart, as a whole burnt-offering, or a prayer-offering, or a whole peace-offering, the priests shall have 3/4 of a shekel and......zars of silver for each, and, in case of a prayer-offering they shall have in addition to this fee the trimmings and the joints — but the skin and the fat of the inwards and the feet and the rest of the flesh the owner of the sacrifice shall have.

child tomb Tofet reconstruction

For a bird, domestic or wild, as a whole peace-offering, or a sacrifice-to-avert-calamity or an oracular sacrifice, the priests shall have 3/4 of a shekel of silver and 2 zars for each; but the flesh shall belong to the owner of the sacrificed. For a bird, or sacred first-fruits, or a sacrifice of game, or a sacrifice of oil, the priests shall have 10 gerahs for each; but ... . ...

In case of every prayer-offering that is presented before the gods, the priests shall have the trimmings and the joints; and in the case of a prayer-offering...For a cake, and for milk, and for every sacrifice which a man may offer, for a meal-offering.....

For every sacrifice which a man may offer who is poor in cattle, or poor in birds, the priests shall not have anything ....Every freeman and every slave and every dependent of the gods and all men who may sacrifice...., these men shall give for the sacrifice at the rate prescribed in the regulations.....

Every payment which is not prescribed in this table shall be made according to the regulations which the superintendents of the dues fixed in the time of Khalasbaal, son of Bodtanith, and Khalasbaal, son of Bodeshmun, and their colleagues. Every priest who shall shall accept payment beyond what is prescribed in this table shall be fined....

Aristotle on The Constitution of Carthage

On The Constitution of Carthage, Aristotle (384-323 B.C.) wrote in “Politics” around 340 B.C.: “The Carthaginians are also considered to have an excellent form of government, which differs from that of any other state in several respects, though it is in some very like the Spartan. Indeed, all three states — the Spartan, the Cretan, and the Carthaginian — nearly resemble one another, and are very different from any others. Many of the Carthaginian institutions are excellent. The superiority of their constitution is proved by the fact that the common people remain loyal to the constitution. The Carthaginians have never had any rebellion worth speaking of, and have never been under the rule of a tyrant. Among the points in which the Carthaginian constitution resembles the Spartan are the following: The common tables of the clubs answer to the Spartan phiditia, and their magistracy of the Hundred-Four to the Ephors; but, whereas the Ephors are any chance persons, the magistrates of the Carthaginians are elected according to merit — this is an improvement. They have also their kings and their Gerousia, or council of elders, who correspond to the kings and elders of Sparta. Their kings, unlike the Spartan, are not always of the same family, nor that an ordinary one, but if there is some distinguished family they are selected out of it and not appointed by seniority — this is far better. Such officers have great power, and therefore, if they are persons of little worth, do a great deal of harm, and they have already done harm at Sparta. [Source: “The Politics of Aristotle,” trans. Benjamin Jowett (Colonial Press, 1900), pp. 49-51]

“Most of the defects or deviations from the perfect state, for which the Carthaginian constitution would be censured, apply equally to all the forms of government which we have mentioned. But of the deflections from aristocracy and constitutional government, some incline more to democracy and some to oligarchy. The kings and elders, if unanimous, may determine whether they will or will not bring a matter before the people, but when they are not unanimous, the people decide on such matters as well. And whatever the kings and elders bring before the people is not only heard but also determined by them, and any one who likes may oppose it; now this is not permitted in Sparta and Crete. That the magistrates of five who have under them many important matters should be co-opted, that they should choose the supreme council of One Hundred, and should hold office longer than other magistrates (for they are virtually rulers both before and after they hold office) — these are oligarchical features; their being without salary and not elected by lot, and any similar points, such as the practice of having all suits tried by the magistrates, and not some by one class of judges or jurors and some by another, as at Sparta, are characteristic of aristocracy.

The Decline of the Carthaginian Empire by William Turner

“The Carthaginian constitution deviates from aristocracy and inclines to oligarchy, chiefly on a point where popular opinion is on their side. For men in general think that magistrates should be chosen not only for their merit, but for their wealth: a man, they say, who is poor cannot rule well — he has not the leisure. If, then, election of magistrates for their wealth be characteristic of oligarchy, and election for merit of aristocracy, there will be a third form under which the constitution of Carthage is comprehended; for the Carthaginians choose their magistrates, and particularly the highest of them — their kings and generals — with an eye both to merit and to wealth. But we must acknowledge that, in thus deviating from aristocracy, the legislator has committed an error. Nothing is more absolutely necessary than to provide that the highest class, not only when in office, but when out of office, should have leisure and not disgrace themselves in any way; and to this his attention should be first directed. Even if you must have regard to wealth, in order to secure leisure, yet it is surely a bad thing that the greatest offices, such as those of kings and generals, should be bought. The law which allows this abuse makes wealth of more account than virtue, and the whole state becomes avaricious.

“For, whenever the chiefs of the state deem anything honorable, the other citizens are sure to follow their example; and, where virtue has not the first place, their aristocracy cannot be firmly established. Those who have been at the expense of purchasing their places will be in the habit of repaying themselves; and it is absurd to suppose that a poor and honest man will be wanting to make gains, and that a lower stamp of man who has incurred a great expense will not. Wherefore they should rule who are able to rule best. And even if the legislator does not care to protect the good from poverty, he should at any rate secure leisure for them when in office. It would seem also to be a bad principle that the same person should hold many offices, which is a favorite practice among the Carthaginians, for one business is better done by one man.

“The government of the Carthaginians is oligarchical, but they successfully escape the evils of oligarchy by enriching one portion of the people after another by sending them to their colonies. This is their panacea and the means by which they give stability to the state. Accident favors them, but the legislator should be able to provide against revolution without trusting to accidents. As things are, if any misfortune occurred, and the bulk of the subjects revolted, there would be no way of restoring peace by legal methods.

Carthage Military

Polybius wrote in “Rome at the End of the Punic Wars”: “If we descend to a more particular comparison, we shall find, that with respect to military science, for example, the Carthaginians, in the management and conduct of a naval war, are more skillful than the Romans. For the Carthaginians have derived this knowledge from their ancestors through a long course of ages; and are more exercised in maritime affairs than any other people. But the Romans, on the other hand, are far superior in all things that belong to the establishment and discipline of armies. For this discipline, which is regarded by them as the chief and constant object of their care, is utterly neglected by the Carthaginians; except only that they bestow some little attention upon their cavalry. The reason of this difference is, that the Carthaginians employ foreign mercenaries; and that on the contrary the Roman armies are composed of citizens, and of the people of the country. [Source: Polybius “Rome at the End of the Punic Wars”: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 166-193]

Now in this respect the government of Rome is greatly preferable to that of Carthage. For while the Carthaginians entrust the preservation of their liberty to the care of venal troops; the Romans place all their confidence in their own bravery, and in the assistance of their allies. From hence it happens, that the Romans, though at first defeated, are always able to renew the war; and that the Carthaginian armies never are repaired without great difficulty. Add to this, that the Romans, fighting for their country and their children, never suffer their ardor to be slackened; but persist with the same steady spirit till they become superior to their enemies. From hence it happens, likewise, that even in actions upon the sea, the Romans, though inferior to the Carthaginians, as we have already observed, in naval knowledge and experience, very frequently obtain success through the mere bravery of their forces. For though in all such contests a skill in maritime affairs must be allowed to be of the greatest use; yet, on the other hand, the valor of the troops that are engaged is no less effectual to draw the victory to their side.

Now the people of Italy are by nature superior to the Carthaginians and the Africans, both in bodily strength, and in courage. Add to this, that they have among them certain institutions by which the young men are greatly animated to perform acts of bravery.

Carthage Economy

Polybius wrote in “Rome at the End of the Punic Wars”: “In things that regard the acquisition of wealth, the manners also, and the customs of the Romans, are greatly preferable to those of the Carthaginians. Among the latter, nothing is reputed infamous, that is joined with gain. But among the former, nothing is held more base than to be corrupted by gifts, or to covet an increase of wealth by means that are unjust. For as much as they esteem the possession of honest riches to be fair and honorable, so much, on the other hand, all those that are amassed by unlawful arts, are viewed by them with horror and reproach. The truth of this fact is clearly seen in the following instance. Among the Carthaginians, money is openly employed to obtain the dignities of the state: but all such proceeding is a capital crime in Rome. As the rewards, therefore, that are proposed to virtue in the two republics are so different, it cannot but happen, that the attention of the citizens to form their minds to virtuous actions must be also different. [Source: Polybius “Rome at the End of the Punic Wars”: Oliver J. Thatcher, ed., “The Library of Original Sources” (Milwaukee: University Research Extension Co., 1907), Vol. III: The Roman World, pp. 166-193]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018