AGRICULTURE IN ANCIENT EGYPT

The ancient Egyptians were fortunate in inhabiting the fertile valley of the Nile. The river's annual flood deposited a fresh layer of silt renewing the fertility of the soil, and ensuring that, for the most part, the country was prosperous and the population sufficiently fed. [Source: ABZU, University of Chicago Oriental Institute, oi-archive.uchicago.edu ]

The ancient Egyptians were fortunate in inhabiting the fertile valley of the Nile. The river's annual flood deposited a fresh layer of silt renewing the fertility of the soil, and ensuring that, for the most part, the country was prosperous and the population sufficiently fed. [Source: ABZU, University of Chicago Oriental Institute, oi-archive.uchicago.edu ]

Egyptian agriculture was tied to the annual cycles of the Nile, which flooded its banks around the same time every year and deposited new top soil. Planting began after the flood waters receded. The high water reached the First Cataract (present-day Aswan) around September and the Nile Delta around October. The fertile soil left behind and abundant water produced bumper crops, which in turned filled the royal granaries and freed people to do things other than produce food. This was the engine that made the entire Egyptian civilization prosper.

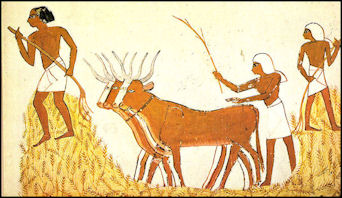

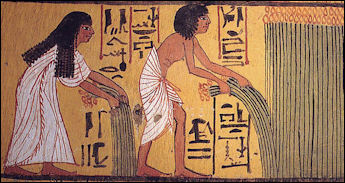

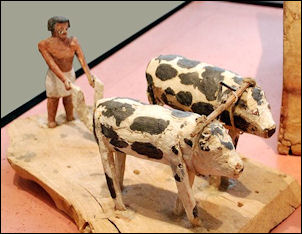

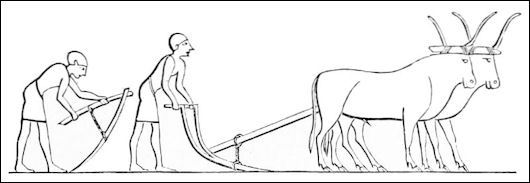

Agriculture advancements credited to the ancient Egyptians include 1) the ox-drawn plough, 2) irrigation, 3) the sickle, a curved blade used for cutting and harvesting grain, and the shadoof, a long balancing pole with a weight on one end and a bucket on the other. The ox-drawn plough — - a plough pulled by oxen — revolutionized agriculture. Modern versions of the plough are still widely used today Egyptian irrigation consisted of canals and irrigation ditches primarily used to harness Nile river’s yearly flood and bring water to distant fields. The shadoof’s bucket could easily be filled with water and raised to bring water to higher ground. [Source: Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com]

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Agriculture in Egypt from Pharaonic to Modern Times” by Alan K. Bowman and Eugene Rogan (1999) Amazon.com;

“A Companion to Ancient Agriculture (Blackwell) by David Hollander and Timothy Howe (2020) Amazon.com;

“Garden of Egypt: Irrigation, Society, and the State in the Premodern Fayyum by Brendan Haug (2024) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Irrigation: A Study of Irrigation Methods and Administration in Egypt (Classic Reprint) by Clarence T. Johnston (1901) Amazon.com;

“The Gift of the Nile?: Ancient Egypt and the Environment (Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections) by Egyptian Expedition, Thomas Schneider, Christine L. Johnston (2020) Amazon.com;

“The Nile and Ancient Egypt: Changing Land- and Waterscapes, from the Neolithic to the Roman Era”, Illustrated by Judith Bunbury (2019) Amazon.com;

“Climate Change in the Middle East and North Africa: 15,000 Years of Crises, Setbacks, and Adaptation” by William R. Thompson and Leila Zakhirova (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Dawn of Agriculture and the Earliest States in Genesis 1-11" (Routledge Studies in the Biblical World) by Natan Levy (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Neolithic Revolution in the Near East: Transforming the Human Landscape”

by Alan H. Simmons and Dr. Ofer Bar-Yosef (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Origins of Agriculture: An International Perspective” by C. Wesley Cowan, Paul Minnis, et al. (2006) Amazon.com;

“Plant Domestication and the Origins of Agriculture in the Ancient Near East”

by Shahal Abbo, Avi Gopher (2022) Amazon.com;

Irrigation in Ancient Egypt

The Egyptians built a complex network of dikes and canals to move water from the flooded Nile to irrigated fields. The irrigation system was decentralized, scholars believe, because the Nile flood plain was divided into a "series of natural basins that fill up sequentially when the river overflows the levees along the main channel." There was no way for an upriver district to take water away from down river districts until the Aswan Dam was completed in the 1960s.

The Egyptians built a complex network of dikes and canals to move water from the flooded Nile to irrigated fields. The irrigation system was decentralized, scholars believe, because the Nile flood plain was divided into a "series of natural basins that fill up sequentially when the river overflows the levees along the main channel." There was no way for an upriver district to take water away from down river districts until the Aswan Dam was completed in the 1960s.

John Baines of the University of Oxford wrote: “Egyptian texts say little about irrigation and the provision of water. Exceptions are biographies of local leaders of the disunited First Intermediate Period (c.2125-1975 B.C.), who claimed that they built canals and supplied water to their own people when others had none. In more prosperous times such matters may have been taken for granted or not thought worth mentioning in public texts. [Source: John Baines, BBC, Professor of Egyptology at the University of Oxford, February 17, 2011 |::|]

One of the simplest kinds of water-lifting devices is called a “shadoof” . It is a seesaw-like lever with a weight on one side of the fulcrum and a rope with a bucket on the other side. The bucket is lowered into a well by tugging on the rope. When the bucket is filled water the weight on the other side of fulcrums lifts it out. These devices are most commonly used in the Nile today, where the water is fairly close to the surface.

The more sophisticated water wheel, or “sakia” , is useful moving large amounts of water. It consists of a vertical wheel with buckets around the perimeter that lifts water of out a canal or water source and dumps into an irrigation ditch. The water wheel is connected to a vertical cogged wheel, which in turn is connected to a horizontal cogged wheel that is turned by oxen or water buffalo yoked to a shaft coming from the wheel. The animals are blindfolded so they are not distracted or scared. If they get spooked they may try to run off and may break the wheel.

Technical problems posed by the large amount of silt carried down by the Nile and the ensuing rise in water levels included building higher and higher levees, dredging large amounts of slit, blocking off natural drainage channels, creating channels to release floods and building dams to control floods.

Crops in Ancient Egypt

harvest The Egyptians cultivated barley, emmer wheat, beans, chickpeas, flax, and other types of vegetables. They ate a low-fat, high-fiber diet with a lot of grains and consumed a variety of plant oils and fats, bread, milk, lentils, cottage cheese, cakes, onions, meat, dates, melons, milk products, figs, ostrich eggs, almonds, peas, beans, olives, pomegranates, grapes, vegetables, honey, garlic and other foods. The Egyptians ate a variety of grains, including barely and emmer-wheat. Barley was used for making beer. Emmer wheat was used to make bead. Lentils were discovered in an Egyptian tomb dating back to 2000 B.C.).

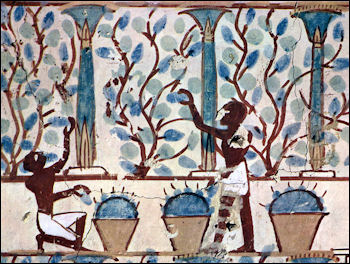

Onions originated in Egypt. Egyptians believed that onions symbolized the many-layered universe. They swore oaths on onions like a modern-time Bible. Grape seeds have been found in 3,000-year-old mummies. Purple peas were found in the tomb of King Tut. Cucumbers were known in ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome. They originated in the foothills of the Himalayas in northern India, where they have been cultivated for more than 3,000 years.

Melons are one the earliest crops along with wheat, barley, various legumes, grapes, dates, pistachios and almonds. Melons are native to Iran, Turkey and the western Asia. They are depicted in an Egyptian tomb painting from 2400 B.C., Greek documents from the 3rd century B.C. mention them. They were described by Pliny the Elder in the 1st century A.D.

John Baines of the University of Oxford wrote: “The principal crops were cereals, emmer wheat for bread, and barley for beer. These diet staples were easily stored. Other vital plants were flax, which was used for products from rope to the finest linen cloth and was also exported, and papyrus, a swamp plant that may have been cultivated or gathered wild. Papyrus roots could be eaten, while the stems were used for making anything from boats and mats to the characteristic Egyptian writing material; this too was exported. A range of fruit and vegetables was cultivated. Meat from livestock was a minor part of the diet, but birds were hunted in the marshes and the Nile produced a great deal of fish, which was the main animal protein for most people. [Source: John Baines, BBC, Professor of Egyptology at the University of Oxford, February 17, 2011 |::|]

See Separate Article: FOOD IN ANCIENT EGYPT: FRUIT, VEGETABLES, SPICES, EATING CUSTOMS africame.factsanddetails.com

Development of Agriculture in Ancient Egypt

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “The geography of Egypt is deeply important in understanding why the Egyptians centered their lives around the Nile. Both before and during the use of canal irrigation in Egypt, the Nile Valley could be separated into two parts, the River Basin or the flat alluvial (or black land soil), and the Red Land or red desert land. The River basin of the Nile was in sharp contrast to the rest of the land of Egypt and was rich with wild life and water fowl, depending on the waxing and waning cycles of the Nile. In contrast, the red desert was a flat dry area which was devoid of most life and water, regardless of any seasonal cycle.” [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com]

The first documented agriculture occurred 11,500 year ago in what Harvard archaeologist Ofer Ban-Yosef calls the Levantine Corridor, between Jericho in the Jordan Valley and Mureybet in the Euphrates Valley. At Mureybit, a site on the banks of the Euphrates, seeds from an uplands area — where the plants from the seeds grow naturally — were found and dated to 11,500 years ago. An abundance of seeds from plants that grew elsewhere found near human sites is offered as evidence of agriculture.

Early agriculture is most famously associated with the Fertile Crescent, an arc of land that extends from southern Turkey into Iraq and Syria and finally to Israel and Lebanon. Seeds of 10,000-year-old cultivated wheat have been discovered at sites in Iraq and northern Syria. The region also produced the first domesticated sheep, goats, pigs and cattle.

Around 10,500 years ago agriculture began developing in the Middle East and China and to a lesser extent in Mexico, the Andes and Nigeria. The is also evidence that bananas and taro were cultivated in the highlands of New Guinea at least 7,000 years ago.

Evidence of Barley and Wheat Consumption 7,000 Years Ago Found Sudan and Nubia

A research team successfully identified ancient barley and wheat residues in grave goods and on teeth from two Neolithic cemeteries in Central Sudan and Nubia, showing that humans in Africa were already exploited domestic cereals 7,000 years ago and thus five hundred years earlier than previously known. The results of the analyses were recently published in the open access journal PLOS ONE. Dr. Welmoed Out from Kiel University said, “With our results we can verify that people along the Nile did not only exploit gathered wild plants and animals but had crops of barley and wheat. ”[Source: Ancientfoods, March 4, 2015]

These types of crops were first cultivated in the Middle East about 10,500 years ago and spread out from there to Central and South Asia as well as to Europe and North Africa — the latter faster than expected. “The diversity of the diet was much greater than previously assumed,” states Out and adds: “Moreover, the fact that grains were placed in the graves of the deceased implies that they had a special, symbolic meaning. ”

The research team, coordinated by Welmoed Out and the environmental archaeologist Marco Madella from Barcelona, implemented, among other things, a special high-quality light microscope as well as radiocarbon analyses for age determination. Hereby, they were supported by the fact that mineral plant particles, so-called phytoliths, survive very long, even when other plant remains are no longer discernible. In addition, the millennia-old teeth, in particular adherent calculus, provide evidence on the diet of these prehistoric humans due to the starch granules and phytoliths contained therein

Inundation of the Nile

According to Minnesota State University, Mankato: “The Nile in it's natural state goes through periods of inundation and relinquishment. The inundation of the Nile-a slightly unpredictable event-was the time of greatest fertility for Egypt. As the banks rose, the water would fill the man-made canals and canal basins and would water the crops for the coming year. However, if the inundation was even twenty inches above or below normal, it could have massive consequences upon the Egyptian agricultural economy. Even with this variability, the Egyptians were able to easily grow tree crops and vegetable gardens in the lower part of the Nile Valley, while at higher elevations, usually near levees, the Nile Valley was sparsely planted.” [Source: Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com]

Nile flood plain limits

According to Plumbing & Mechanical Magazine: “From ancient times, the rise and fall of the River Nile portended periods of famine or good fortune for the peoples of Egypt. Other than wells, the River Nile is the only source of water in the country. During an idyllic year, the flooding of the Nile would begin in July, and by September its receding waters would deposit a rich, black silt in its wake for farming. Before taming the river, however, the ancient Egyptians had to overcome the river’s peculiar problem. The Nile runs along an alluvial plain, the ebb and tide of the Nile corresponding to an annual movement of the ground. When the Nile is the lowest, the ground completely dries up. When it floods, the water seeps into the dry soil and causes the ground to rise as much as a foot or two like some bloated sponge. As the inundation subsides the ground settles again to its original dry level, but never settles evenly.” [Source: Plumbing & Mechanical Magazine, July 1989, theplumber.com]

John Baines of the University of Oxford wrote: “The Nile's annual inundation was relatively reliable, and the floodplain and Delta were very fertile, making Egyptian agriculture the most secure and productive in the Near East. When conditions were stable, food could be stored against scarcity. The situation, however, was not always favourable. High floods could be very destructive; sometimes growth was held back through crop failure due to poor floods; sometimes there was population loss through disease and other hazards. Contrary to modern practice, only one main crop was grown per year. [Source: John Baines, BBC, Professor of Egyptology at the University of Oxford, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Crops could be planted after the inundation, which covered the Valley and Delta in August and September; they needed minimal watering and ripened from March to May. Management of the inundation in order to improve its coverage of the land and to regulate the period of flooding increased yields, while drainage and the accumulation of silt extended the fields. Vegetables grown in small plots needed irrigating all year from water carried by hand in pots, and from 1500 B.C. by artificial water-lifting devices. Some plants, such as date palms, whose crops ripened in the late summer, drew their water from the subsoil and needed no other watering. |::|

Harnessing the Nile to Create Ancient Egyptian Civilization

According to Plumbing & Mechanical Magazine: “The name Egypt means “Two Lands,” reflecting the two separate kingdoms of Upper and Lower prehistoric Egypt – Delta region in the north and a long length of sandstone and limestone in the south. In 3000 B.C., a single ruler, Menes, unified the entire land and set the stage for an impressive civilization that lasted 3,000 years. He began with the construction of basins to contain the flood water, digging canals and irrigation ditches to reclaim the marshy land. [Source: Plumbing & Mechanical Magazine, July 1989, theplumber.com /~/]

“From these earliest of times, so important was the cutting of a dam that the event was heralded by a royal ceremony. King Menes is credited with diverting the course of the Nile to build the city of Memphis on the site where the great river had run. By 2500 B. C., an extensive system of dikes, canals and sluices had developed. It remained in use until the Roman occupation, circa 30 B.C. – 641 A.D. For pure water, the Egyptians depended upon wells. Their prowess in divining hidden sources is shown in the “Well of Joseph,” constructed about 3000 B.C. near the Pyramids of Gizeh. Workers had to dig through 300 feet of solid rock to tap into the water.” /~/

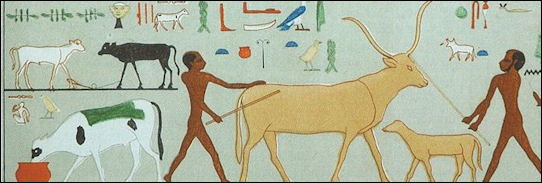

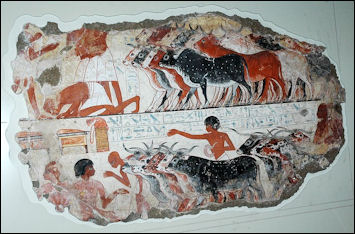

livestock

John Baines of the University of Oxford wrote: “Throughout antiquity, Egypt's standing relied on its agricultural wealth and, therefore, on the Nile. Agriculture had not been the original basis of subsistence, but evolved, together with the land itself, during the millennia after the last Ice Age ended around 10,000 B.C., expanding greatly from about 4500 B.C. onward. [Source:John Baines, BBC, Professor of Egyptology at the University of Oxford, February 17, 2011 |::|]

By 3100 B.C. the Nile Valley and Delta had coalesced into a single entity that was the world's first large nation state. As well as providing the region's material potential, the Nile and other geographical features influenced political developments and were significant in the development of Egyptian thought. The land continued to develop and its population increased until Roman times. Important factors in this process were unity, political stability, and the expansion of the area of cultivated land. The harnessing of the Nile was crucial to growth.” |::|

“It is uncertain how early and by how much the inundation was regulated. By the Middle Kingdom (c.1975-1640 B.C.) basin irrigation, in which large sections of the floodplain were managed as single units, was well established, but it may not have been practised in the Old Kingdom (c.2575-2150 B.C.), when the great pyramids were built. The only area where there was major irrigation work before Graeco-Roman times was the Faiyum, a lakeside oasis to the west of the Nile. Here Middle Kingdom kings reclaimed land by controlling the water flow along a side river channel and directing it to irrigate extra land while lake water levels were lowered. Their scheme did not last. |::|

Agrarian Production in Ancient Egypt

Ben Haring of Universiteit Leiden wrote: ““There is insufficient data to establish the amount of agrarian production (grain or otherwise) in ancient Egypt. Quantitative data are scarce and their chronological distribution is uneven. Estimates have been made, however, of the population and the total extent of fertile area during the Pharaonic and Greco-Roman periods. The figures usually quoted by Egyptologists are those arrived at by Butzer on the basis of geological surveys, as well as textual and archaeological data on ancient demography and agrarian technology. Butzer calculated a fertile area of 22,400 sq. kilometers. and a population of 2.9 million in the early Ramesside Period (about 1250 B.C.), and 27,300 sq. kilometers. with a population of 4.9 million in the Ptolemaic Period (about 150 B.C.). The underlying assumption is that 130 persons could live from the production of one square kilometer in the former, and 180 in the latter period. Their food would basically include wheat and barley, vegetables, dates, and fish, and for the well-to-do the diet would include meat and fruit. The increase in agrarian production per square kilometer in the Greco-Roman Period can be explained by improvements in agricultural technology (irrigation devices, new crops), and perhaps by a more efficient agrarian administration. [Source: Ben Haring, Universiteit Leiden, Netherlands, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

hoe and plow

“Some documents provide data concerning grain production per square kilometer, although there remain uncertainties about the measures employed and the quality of the fields referred to. Administrative texts from the Ramesside Period (1295 - 1069 B.C.) suggest a norm of 2,700 to 2,900 liters per hectare (l/ha) for basin land—that is, fields of the best quality, submerged by the annual rise of the Nile in antiquity. (Conversion of liters to kilos is apparently a less than reliable process: references featuring the conversion display diverging estimates, in which the equivalent of one liter of grain varies between 0.512 and 0.705 kilos). The Ramesside quota match those found in records from early twentieth-century Egypt (varying between approximately 2,000 and 2,800 l/ha for wheat, and between 2,500 and 3,400 l/ha for barley). Less productive types of land were expected to yield three-quarters or half of these amounts. It is uncertain how much of the land available for agriculture was actually sown with wheat or barley, rather than vegetables, fruit trees, fodder for animals, or flax. It is assumed, however, that most of the basin land was used for cultivating grain crops.

“Ramesside sources inform us about the organization of agrarian production insofar as it is connected with temples and government departments. The personnel of these institutions were called ihuty (iHwtj; plural: iHwtjw). According to some texts, an ihuty was responsible for the yearly production of almost 16,000 liters of grain. For this he would have to work 5.5 to 6 hectares of basin land. The most important agrarian document of this period, Papyrus Wilbour, records even larger areas as the responsibility of an individual ihuty. Together, these sources suggest that the word ihuty refers to a supervisor rather than (or as well as) a member of the actual workforce. On a higher level, the ihuty were supervised by scribes, priests, or high state and temple officials.”

Famine in Ancient Egypt

Laurent Coulon of the University of Lyon wrote: “In ancient Egypt, food crises were most often occasioned by bad harvests following low or destructive inundations. Food crises developed into famines when administrative officials— state or local—were unable to organize storage and redistribution systems. Food deprivation, aggravated by hunger-related diseases, led to increased mortality, migrations, and social collapse. In texts and representations, the famine motif is used as an expression of chaos, emphasizing the political and theological role of the king (or nomarch or god) as “dispenser of food.” [Source: Laurent Coulon, University of Lyon, France,UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

“In pre-modern times, food production in Egypt was heavily dependent on cultivation of the Nile Valley lands, watered and fertilized by the annual flood. Because the inundation level was irregular, food crises recurred fairly frequently, ranging from food shortages to famine, a term which, strictly speaking, should be reserved for “critical shortage of essential foodstuffs, leading through hunger to a substantially increased mortality rate in a community or region, and involving a collapse of the social, political and moral order”. The correspondence between Hekanakht, a landowner who lived during the early 12th Dynasty, and his dependents gives an account of the serious difficulties encountered by various strata of society at a time when the Nile only partially flooded the cultivated lands. Epigraphic and literary sources give numerous mentions of successive years of low flood, exemplified by the biblical episode in which Joseph interprets Pharaoh’s dream of seven lean cows and seven dried stalks of wheat. At the beginning of the First Intermediate Period, Ankhtify’s autobiography recounts a dark period when, except in his nome, “all of Upper Egypt was dying of hunger and people were eating their children.” Paleopathologic studies also provide cases of nutritional stress and high mortality at various times, but it is only for the Greco-Roman Period that we possess the papyrological documentation for a historical overview of famines in ancient Egypt; the study of such documentation shows—not surprisingly—the coincidence of famines with plague epidemics.

Relief showing starving Bedouins from Unas causeway

“Famines were also capable of prompting migrations of population. Ankhtifi’s autobiography mentions that “the whole country has become like locusts going upstream and downstream.” Migrations probably played a significant role in the birth of Egyptian civilization during the Holocene Period, when drastic climatic changes and increasing aridity may have forced inhabitants of the Western and Eastern Deserts to settle on the banks of the Nile.

“The consequences of low or destructive inundations depended to a large degree on the ability of administrative officials—state or local—to anticipate subsistence crises: sufficient storage of surpluses from one year to the next and an efficient redistribution system could counter bad harvests. Conversely, famine clearly correlates with mismanagement of the state administration—for example, during the 20thDynasty, when the workmen of Deir el- Medina were compelled to go on strike to obtain their salaries. The prosperity of the Egyptian state was nevertheless famous throughout the Near East, and New Kingdom pharaohs used grain supplies as diplomatic gifts when their allies, especially the Hittites, were facing starvation; on the other hand, the Egyptian army commonly induced famine artificially, through destruction of harvests and cattle, to subdue foreign enemies.

“The Egyptians viewed food deprivation as a liminal experience, approaching chaos. Because the experience of chaos was included as a kind of “rite of passage” in the funerary ritual, the deceased were therefore required to suffer hunger and thirst before being regenerated by funerary offerings. The evocation of the elite suffering famine is also an essential feature of the social anarchy described in texts such as The Prophecy of Neferty and The Admonitions of Ipuwer. Conversely, representations occasionally emphasize the opulence of the Egyptians from the Nile Valley by contrasting them with the starving nomadic tribes, as we see, for example, in 5th-Dynasty reliefs depicting emaciated Bedouin and in the 12th-Dynasty relief of a cowherd in a tomb of Meir. “Nourishing the land” and “giving bread to the hungry” are the basic definitions of the role of the king and high officials; the evocation of famine in hieroglyphic texts is embedded in this ideological discourse. Recent studies suggest that the repeated evocation of famines in First Intermediate Period texts reflects the employment of a new rhetoric of the nomarch as “dispenser of food,” featuring realistic descriptions rather than the standard clichés . To use these texts as evidence of climatic changes is therefore misleading, the more so as this self-presentation of the nomarch is still attested during the Middle Kingdom. Divine intervention against famine is also a frequent motif of Late Period texts, among the most famous of which is the so-called “Famine Stela” at Sehel, a Ptolemaic inscription celebrating the prosperity granted to the region by the god Khnum after a seven-year famine during the reign of Djoser.”

Agriculture in Ancient of Sudan-Nubia

According to ancientsudan.org: “Agriculture along the narrow strip of the Nile valley provided Nubians with their necessary food supply. Therefore most of the Nubian populations were farmers. Each year the Nile flooded Upper Nubia providing silt for the agricultural lands. The Kushites used the Shaduf (a traditional device operated manually for raising water from a lower depression that is connected to a source of water, to a higher depression where the water is distributed to farther depressions to irrigate the field/s) for watering their farms.1 Sometime in the late Meroitic period, they transfered to the use of Saquia (a water wheel), which was brought to Nubia from Southwest Asia. [Source: Ancientfoods,ancientsudan.org, May 13, 2011]

“There are numerous hafirs (a depression dug on flat ground to collect rain water) discovered in Nubia including many at Musawwarat es Sufra.3 However hafirs would not have provided enough water for watering the farms. The only Kushite dam used for water storage was found at Shaq el Ahmar.4

A concern for food might have triggered the Kushite control for other regions like the Buttana in the east, where sorghum was easily grown depending on rain. As a matter of fact, it is evident from the haffirs dug there in the Meroitic period that Kush had certainly practiced considerable powers over the Buttana during that period.

Nomads wondered the semi-arid regions on both sides of the Nile with their flocks in search of good pastures. The Kushites were in continues warfare with these hostile nomads. However both the nomads and the farmers have in many cases benefited from each other; an exchange of animal and agricultural products was probably a usual practice. Also, the Nubian farmers allowed the nomads to herd their flocks on harvested farms in return for the dung of the animals which fertilized the farms.8

A wall painting at Kerma dating to 1600 B.C. depicts a well in profile with a robe pulling a buck of water. Hafirs have been discovered in various locations in Nubia. At every excavated Nubian settlement, hafirs were present. At Kawa and Musawwarat es Sufra there were large numbers of hafirs. Therefore, it becomes obvious that the Kushite main source of water was from wells. Wells would be shallow if the settlements were by the Nile, and would be deep if they were on regions far from the river.

Gebel Moya — A Very Old Agricultural Site in Southern Sudan

Isabelle Vella Gregory wrote: Gebel Moya is a large agricultural-pastoral site located below the Nile’s Sixth Cataract in Sudan. It lies between the Blue Nile and White Nile. It was first excavated by Henry Wellcome in the early twentieth century and was known as a cemetery until 2017, when fieldwork was renewed by a joint international mission. Current excavations show that, in addition to being a major cemetery, the site bears traces of Mesolithic habitation. Over a period of 5,000 years the area witnessed rapid climate change.[Source Isabelle Vella Gregory, University of Cambridge, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2024 escholarship.org ]

Gebel Moya lies around 240 kilometers south of Khartoum. The name Gebel Moya means, in Arabic, “Mountain of Water” and refers to the nearby village and mountain valley in an area that is now arid. Archaeological remains are present in the valley above the village. Officially, these are known as Site 100, although the locals simply refer to the area as Gebel Moya. The nearest large town is Sennar.

The ongoing work of the current mission, directed by Ahmed Adam, Michael Brass and Isabelle Vella Gregory has confirmed the site to be a major agro-pastoral cemetery stretching over 5,000 years, and with firm traces of Mesolithic habitation. Thus far, the site has yielded evidence of rapid historic climate change and the second oldest domesticated sorghum in the world. Ongoing work is focused on reconstructing the ancient flora and fauna. It is now clear that Site 100, long considered insignificant by scholars, was home to dynamic communities across the millennia.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Gebel Moya (Site 100) by Isabelle Vella Gregory UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology escholarship.org

Ancient Egyptian Cotton Reveals Secrets about Domesticated Crop Evolution

On 2012, scientists from the University of Warwick studying 1,600-year-old cotton from the banks of the Nile said they found what they believe is the first evidence that punctuated evolution has occurred in a major crop group within the relatively short history of plant domestication. The findings offer an insight into the dynamics of agriculture in the ancient world and could also help today's domestic crops face challenges such as climate change and water scarcity. [Source: University of Warwick, Science Daily, April 2, 2012

Science Daily reported: “The researchers, led by Dr Robin Allaby from the School of Life Sciences at the University of Warwick, examined the remains of ancient cotton at Qasr Ibrim in Egypt's Upper Nile using high throughput sequencing technologies. This is the first time such technology has been used on ancient plants and also the first time the technique has been applied to archaeological samples in such hot countries.

For archaeologists, the results also shed light on agricultural development in the ancient world. There has long been uncertainty as to whether ancient Egyptians had imported domesticated cotton from the Indian subcontinent, as had happened with other crops, or whether they were growing a native African variety which had been domesticated locally. The study's findings that the Qasr Ibrim seeds were of the G. herbaceum variety, native to Africa, rather than G.arboreum, which is native to the Indian subcontinent, represents the first molecular-based identification of archaeobotanical cotton to a species level.

“Dr Allaby said the findings confirm there was an indigenous domestication of cotton in Africa which was separate from the domestication of cotton in India. "The presence of cotton textiles on Egyptian and Nubian sites has been well documented but there has always been uncertainty among archaeologists as to the origin of these. "It's not possible to identify some cotton varieties just by looking at them, so we were asked to delve into the DNA. "We identified the African variety--G. herbaceum, which suggest that domesticated cotton was not a cultural import--it was a technology that had grown up independently."”

The site is located about 40 kilometers from Abu Simbel and 70 kilometers from the modern Sudanese border on the east bank of what is now Lake Nasser. They also studied South American samples from sites in Peru and Brazil aged between 800 and nearly 4,000 years old. The results showed that even over the relatively short timescale of a millennia and a half, the Egyptian cotton, identified as G. herbaceum, showed evidence of significant genomic reorganisation when the ancient and the modern variety were compared. However closely-related G.Barbadense from the sites in South America showed genomic stability between the two samples, even though these were separated by more than 2,000 miles in distance and 3,000 years in time.

This divergent picture points towards punctuated evolution--long periods of evolutionary stability interspersed by bursts of rapid change--having occurred in the cotton family. Dr Allaby said: "We think of evolution as a very slow process, but as we analyse more genome information we can see that there's been a huge amount of large-scale proactive change during recent history. Our results for the cotton from Egypt indicate that there has been the potential for more adaptive evolution going on in domesticated plant species than was appreciated up until now. Plants that are local to their particular area will develop genes which allow them to better tolerate the stresses they find in the environment around them. It's possible that cotton at the Qasr Ibrim site has adapted in response to extreme environmental stress, such as not enough water. This insight into how domesticated crops evolved when faced with environmental stress is of value for modern agriculture in the face of current challenges like climate change and water scarcity.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024