TRADE IN ANCIENT EGYPT

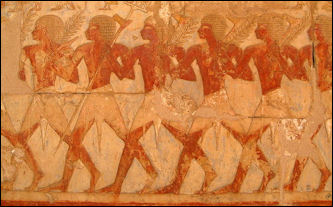

African products presented

to the pharaoh The Egyptians carried out commerce by ships on the Nile and the Mediterranean. They also conducted overland trade. Way stations were set up at oases and along the Nile and other major trade routes. Money had not yet been invented but goods were collected at a central area and distributed by the government.

Ben Haring of Universiteit Leiden wrote: “Trade is at the core of modern economies, hence also of economy as a scholarly The oldest economic texts from ancient Egypt concern sales of land (such as the inscriptions in the 4th-Dynasty tomb of Metjen) and houses or tombs. Texts referring to trade, local and long distance, from later periods abound. Depictions in Old and New Kingdom tombs show marketplaces and merchants’ ships.” [Source: Ben Haring, Universiteit Leiden, Netherlands, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

The ancient Egyptians obtained gold from Nubia beginning in the Middle Kingdom. Gold was called “ nub” in ancient Egypt and may be the source of the name Nubia. Ebony, ivory, leopard skins and incenses also came from Nubia. The ancient Egyptians traded for cedar from Byblos (present-day Lebanon). Boats from Byblos hugged the Mediterranean coast and traveled up the Nile. The ancient Egyptians also obtained goods from India and China. A strand of silk has been found on a 3000-year-old Egyptian mummy. This astonishing discovery provides evidence of trade between ancient China and the Mediterranean 1,800 years before Marco Polo traveled the famed Silk Road

RELATED ARTICLES:

ANCIENT EGYPT'S RELATIONS WITH OTHER STATES africame.factsanddetails.com

SEA TRAVEL IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

RIVER TRANSPORT AND USES OF BOATS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

SHIPS AND BOATS IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com ;

TYPES OF ANCIENT EGYPTIAN BOATS africame.factsanddetails.com ;

MERER'S DIARY: 4,600-YEAR-OLD LOGBOOK ABOUT PYRAMID BOATMEN africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“War & Trade with the Pharaohs: An Archaeological Study of Ancient Egypt's Foreign Relations” by Garry J. Shaw (2020) Amazon.com;

“Pharaoh's Land and Beyond: Ancient Egypt and Its Neighbors” by Pearce Paul Creasman and Richard H. Wilkinson (2017) Amazon.com;

“From Egypt to Mesopotamia: A Study of Predynastic Trade Routes” by Samuel Mark (1997) Amazon.com;

“Threads of Contact: Tracing the Relationship Between Egypt and the Southern Levant through Textile Tools” by Chiara Spinazzi-Lucchesi (2025) Amazon.com;

“Jewels of Ancient Nubia” by Yvonne Markowitz, Denise Doxey (2014) Amazon.com;

“Gold and Gold Mining in Ancient Egypt and Nubia: Geoarchaeology of the Ancient Gold Mining Sites in the Egyptian and Sudanese Eastern Deserts” by Rosemarie Klemm and Dietrich Klemm (2012) Amazon.com;

“Nubian Gold: Ancient Jewelry from Sudan and Egypt” by Peter Lacovara and Yvonne J. Markowitz (2019) Amazon.com

“Tin in Antiquity: Its Mining and Trade Throughout the Ancient World with Particular Reference to Cornwall” by R.D. Penhallurick (2008)

“The Mystery of the Land of Punt Unravelled” (2015) by Ahmed Ibrahim Awale Amazon.com;

“Seafaring Expeditions to Punt in the Middle Kingdom” by Kathryn Bard and Rodolfo Fattovich (2018) Amazon.com;

“Gold, Frankincense, Myrrh, And Spiritual Gifts Of The Magi” by Winston James Head Amazon.com ;

“Frankincense & Myrrh: Through the Ages, and a complete guide to their use in herbalism and aromatherapy today” by Martin Watt and Wanda Sellar Amazon.com ;

“Commerce and Economy in Ancient Egypt” by Andras Hudecz (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Economy of Ancient Egypt: State, Administration, Institutions”

by Mahmoud Ezzamel (2024) Amazon.com;

Obstacles to Trade in Ancient Egypt

Owing to the long serpent-like form of Egypt, the distances between most of the towns were of a disproportionate length; this intercourse was therefore always of a limited nature. The distance from Thebes to Memphis was about 550 kilometers (340 miles), from Thebes to Tanis about 700 kilometers (435 miles), and from Elephantine to Pelusium as much as 940 kilometers (585 miles). It is quite true that in other countries of antiquity, the chief towns were often situate as far apart, but the latter had facilities of intercourse on all sides, while the Egyptian towns, from the nature of the country, possessed neighbours on two sides only. These conditions did not of course tend to incite brisk intercourse between the various parts of the country, and the inhabitants of ancient Egypt (like those of modern date) were ly content with journeys to the neighbouring provinces. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Hatshepsut's expedition

to the Land of Punt There were other obstacles to foreign trade. There were no harbours on the north of the Delta, and the currents off the coast made it very dangerous for ships, while the harbours of the Red Sea could only be reached by four days of desert traveling. The cataracts made it difficult to visit the countries of the Upper Nile. Thus commerce was always somewhat strange to the Egyptians, who gladly left it to the Phoenicians; and the “Great Green One," such as the ocean, was at all times a horror to them. Compared with the Phoenicians, their naval expeditions were insignificant, while in their agriculture, their arts and manufactures, they rose to true greatness.

Texts don’t speak so much about merchants. In the tomb of the oft-named Chaemhet, the superintendent of the granaries under Amenhotep III., there is a picture of marketing in the same small way during the New Kingdom. The great ships which have brought in the import of grain-provision for the state are disembarking in the harbour of Thebes, and whilst most of the sailors are busy discharging the freight, a few slip away quietly to the salesmen who are squatting on the bank before their jars and baskets. Two of these dealers are evidently foreigners, perhaps Syrians; one of the latter is helping his wife to sell her goods, and the very primitive toilette of this lady leads us to conclude that their business is not very flourishing. They seem to be selling food of some kind, while in exchange the sailors are probably giving the grain that they have received out of the cargo as their wages. Goods of some kind at all events are being exchanged, for all the trade of Egypt was carried on by barter, and nothing was given in payment except goods or produce.

Traders in Ancient Egypt

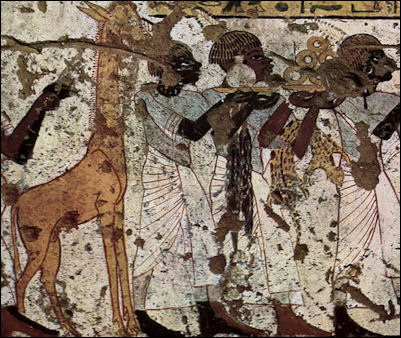

trade involving a giraffe Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia of the CNRS in France wrote: Traders and merchants were certainly part of the urban population, perhaps a significant one, judging from Mesopotamian parallels and from the neighborhoods and harbor facilities in which they lived and worked. Although the opulence and splendor of cities were celebrated in many New Kingdom compositions, in some instances urban markets, “money,” business, and traders were also the objects of praise. Of the Ramesside capital Pi-Ramesse, for example, it was written: “Pleasant is the market-place with/ because of its money there, namely the vine tendrils and business. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“The chiefs of every foreign country come in order to descend with their products”. There the quays were bursting with the bu siness of foreign and Egyptian traders, and with women selling their products, while officials oversaw the arrival of cargo-laden ships and the activities that took place in the harbor areas (as we learn from Sarenput I, governor of Aswan in the early Middle Kingdom and superior of the harbor areas of Elephantine).

“Urban and rural markets were places where people exchanged products and news, frequented by peddlers from remote areas (such as the famous Eloquent Peasant, who came with his small caravan of donkeys from Wadi Natrun to Heracleopolis to trade), while small exchanges of gifts between neighbors cemented social relations within communities. Specialized workers and artisans, usually working fo r the king, also put their skills at the service of customers eager to afford high quality equipment for themselves —the sort of private, non-institutional demand so badly documented in administrative papyri.”

"Scenes of Asiatic Commerce in Theban Tombs (Rek-mi-Re)" from the Tombs of the Noblemen (15th-13th Century B.C.) reads: Coming in peace by the princes of Retenu and all northern countries of the ends of Asia, bowing down in humility, with their tribute upon their backs, seeking that there be given them the breath of life and desiring to be subject to his majesty, for they have seen his very great victories and the terror of him has mastered their hearts. Now it is the Hereditary Prince, Count, Father and Beloved of the God, great trusted man of the Lord of the Two Lands, Mayor and Vizier, Rekh-mi-Re (reign of Thothmosis III), who receives the tribute of all foreign countries...Presenting the children of the princes of the southern countries, along with the children of the princes of the northern countries, who were brought as the best of the booty of his majesty, the King of Upper and Lower Egypt: Men-kheper-Re (Thothmosis III), given life, from all foreign countries, to fill the workshop and to be serfs of the divine offerings of his father Amon, Lord of the Thrones of the Two Lands, according as there have been given to him all foreign countries together in his grasp, with their princes prostrated under his sandals .[Source: James B. Pritchard, “Ancient Near Eastern Texts,” (ANET), Princeton, 1969, pp. 248 web.archive.org]

Ancient Egyptian Trade Routes

John Noble Wilford wrote in New York Times, “Over the last two decades, John Coleman Darnell and his wife, Deborah, hiked and drove caravan tracks west of the Nile from the monuments of Thebes, at present-day Luxor. On these and other desolate roads, beaten hard by millennial human and donkey traffic, the Darnells found pottery and ruins where soldiers, merchants and other travelers camped in the time of the pharaohs. On a limestone cliff at a crossroads, they came upon a tableau of scenes and symbols, some of the earliest documentation of Egyptian history. Elsewhere, they discovered inscriptions considered to be one of the first examples of alphabetic writing.[Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, September 6, 2010 ++]

"The explorations of the Theban Desert Road Survey, a Yale University project co-directed by the Darnells, called attention to the previously underappreciated significance of caravan routes and oasis settlements in Egyptian antiquity. In August 2010, the Egyptian government announced what may be the survey’s most spectacular find: the extensive remains of a settlement — apparently an administrative, economic and military center — that flourished more than 3,500 years ago in the western desert 110 miles west of Luxor and 300 miles south of Cairo. No such urban center so early in history had ever been found in the forbidding desert. ++

"Dr. John Darnell, a professor of Egyptology at Yale, said that the discovery could rewrite the history of a little-known period in Egypt’s past and the role played by desert oases, those islands of springs and palms and fertility, in the civilization’s revival from a dark crisis. Other archaeologists not involved in the research said the findings were impressive and, once a more detailed formal report is published, will be sure to stir scholars’ stew pots. ++

"Finding an apparently robust community as a hub of major caravan routes, Dr. Darnell said, should “help us reconstruct a more elaborate and detailed picture of Egypt during an intermediate period” after the so-called Middle Kingdom and just before the rise of the New Kingdom.At this time, Egypt was in turmoil. The Hyksos invaders from southwest Asia held the Nile Delta and much of the north, and a wealthy Nubian kingdom at Kerma, on the Upper Nile, encroached from the south. Caught in the middle, the rulers at Thebes struggled to hold on and eventually prevail. They were succeeded by some of Egypt’s most celebrated pharaohs, such notables as Hatshepsut, Amenhotep III and Ramses II. ++

"The new research, Dr. Darnell said, “completely explains the rise and importance of Thebes.” From there rulers commanded the shortest route from the Nile west to desert oases and also the shortest eastern road to the Red Sea. Inscriptions from about 2000 B.C. show that a Theban ruler, most likely Mentuhotep II, annexed both the western oasis region and northern Nubia. ++

"With further investigations at Umm Mawagir, Dr. Darnell said, scholars may recognize the desert as a kind of fourth power, in addition to the Hyksos, Nubians and Thebans, in the political equation in those uncertain times. It was perhaps their control of desert roads and alliance with vibrant oasis communities that gave the Thebans an edge in the struggle to control Egypt’s future. In any case, the ruins at a desert crossroads are another wonder of the ancient world. “People always marvel at the great monuments of the Nile Valley and the incredible architectural feats they see there,” Dr. Darnell said in the Yale alumni magazine. “But I think they should realize how much more work went into developing Kharga Oasis in one of the harshest, driest deserts.++

Harkhuf: an Ancient Egyptian Explorer

Harkhuf

John Ray of Cambridge University wrote for the BBC: “The life of Harkhuf is known entirely from the inscriptions in his tomb at Aswan, near the First Cataract of the Nile. Harkhuf ended his days as an honoured courtier, and his importance lies in his early adventures, and the way that he attracted the attention of the royal court. [Source: John Ray, Cambridge University, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“Old Kingdom Egypt took a keen interest in the affairs of its southern neighbour, Nubia. The region was rich in gold, controlled trade with Africa, and was vast and unexplored. The task of Harkhuf's family was to explore it. Harkhuf records how, as a youth, he accompanied his father into the upper country, at the request of King Merenre (c.2287-2278 B.C.). He travelled a considerable distance to a land called Iyam, which probably corresponds to the fertile plain that opens out south of the area of modern Khartoum, where the Blue Nile joins the White. |::|

“On his second expedition Harkhuf travelled alone, bringing back with him exotic gifts, which must have enhanced his status at court. On his third journey, Harkhuf was entrusted to track down the ruler of Iyam, who had gone on a campaign against the southern Libyans, and persuade him to abandon his ambitions. The pharaohs were reluctant to see the expansion of Iyam, which could threaten Egyptian control over the north of Nubia. |::|

“This may have been the high point of Harkhuf's career, but pride of place in his tomb is given to a letter he received from the new king, a boy known to history as Pepi II. Among the treasures brought back from Africa was a pygmy who could do exotic dances. Harkhuf knew this would delight the young ruler. |::|

“The little king's letter about this gift would have been written on papyrus, and perished millennia ago. But the text was transcribed and carved on the wall of the tomb, and is there to this day. It is a combination of official jargon, shot through with schoolboy enthusiasm, and it is clear why Harkhuf chose to take it with him into eternity. It is one of the most vivid letters to survive from the ancient world.” |::|

Expeditions in Ancient Egypt

From the 3rd dynasty to the 20th dynasty, "expeditions were sent to the Sinai and the Eastern Desert to mine or trade for ores such as tin and copper and semiprecious stones such as turquoise, Egyptian alabaster and quartzite."

Heidi Köpp-Junk of Universität Trier wrote: “Two important categories of travelers were members of expeditions and members of the army, both consisting of a variety of occupational categories. Expeditions to Sinai could include “twenty-five different types of government officials, eleven types of specialized local mining officials, eight types of artisans and nine types of laborers”. The same range is evidenced at the Wadi el-Hudi and the Wadi Hammamat in the Middle Kingdom. The officials referred to in the expedition texts are not only high- ranking but from lower ranks as well . Hunters, fowlers, brewers, sandal makers, bakers, scribes, millers, servants, physicians, priests, and mayors are mentioned in the texts. In the New Kingdom, professions connected with horses and chariots, such as charioteers, were attested. [Source: Heidi Köpp-Junk, Universität Trier, Germany, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“Expeditions differed in size and in the profession of their members, depending on the type of material they were sent out to retrieve, or on the goods they were going to trade. For example, quarrying expeditions for precious stones and gems required a greater number of specialists, whereas expeditions for large, heavy blocks required a majority of lessor- skilled workers for the quarrying, and especially the transport, of the stones. In the Old Kingdom, the number of expedition members lies between 80 und 20,000. Senusret I sent to the Wadi Hammamat an expedition that included “18,660 skilled and unskilled workers”. A mission under the reign of Ramesses III counted 3,000 members, including 2,000 common workers and 500 masons. An expedition under Ramesses IV consisted of 408 members in total, among them 50 stone-carriers and 200 transport-carriers. Already from these few pieces of evidence it becomes clear that expedition members came from various professions with a sizable number of common workers among them.

“A calculation of the figures given in the expedition texts reveals that there is evidence for approximately 23,400 members of expeditions in the Old Kingdom, nearly 40,000 in the Middle Kingdom, and 13,622 in the New Kingdom. The explanation as to why the number of expedition members in the New Kingdom is lower in comparison with that of the Old and Middle Kingdoms lies in the fact that there are fewer expedition-related inscriptions from the New Kingdom that survive and they are less detailed than those from the Middle Kingdom. It is assumed nevertheless that the number of travelers increased with the expansion of the Egyptian empire in the New Kingdom, since the expansion promoted a higher degree of mobility within several professions, such as the military and the administration. “Not every expedition that took place is documented; thus the total number of travelers who were on the move as members of expeditions is higher than the documented figures we possess. Furthermore, since the expedition texts frequently mention only the higher ranking members, while the lower grades are often not mentioned, the total figures may conceivably have been much higher.”

Transport and Trade in Ancient Egypt

Trade could be conducted without money. Ben Haring of Universiteit Leiden wrote: “Payment and storage in kind often necessitated the transport of goods in large quantities. Long-distance trade, especially, depended heavily on the infrastructure available. Given the absence of paved roads in ancient Egypt, transport on land (in the Nile Valley and in the desert) entirely depended on manpower and huge numbers of donkeys (camels did not make their appearance in Egypt before the Late Period). Most transport of any substantial scale was by ship; administrative records mention ships capable of loading forty tons of grain or more. Navigation on the Nile meant rowing downstream when heading north, and making use of the wind from the Mediterranean Sea when going south. Traveling from Memphis to Thebes could take two weeks or more. [Source: Ben Haring, Universiteit Leiden, Netherlands, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Ramesside texts specify the costs of grain transport on the Nile as approximately 10 percent of the cargo. Apart from the costs of transport itself, there were tolls and customs to be paid. Tolls had to be paid when passing military strongholds in Egypt and Nubia, although temple ships could be exempted by royal decree. A scene in the tomb of the vizier Rekhmira depicts the collection of dues from towns and fortresses in southern Egypt; among these we find the fortresses of Biga and Elephantine. Customs are associated with international ports of trade. Possible early references are made in two letters from Cyprus in which the pharaoh and the vizier are asked not to permit any claims being made against Cypriotic merchants.

.jpg)

trade of elephant tusks

“Unambiguous documentation on customs is present from the Persian Period, but it may reflect practice already current in the preceding 26th Dynasty. Moreover, Herodotus informs us that that dynasty concentrated trade with Greek merchants in the settlement of Naukratis in the western Delta, which is a further indication of government concern with (and possibly revenues from) foreign trade. This does not mean that trade with foreign merchants was restricted to government institutions, since New Kingdom tomb scenes show Levantine merchants engaging in trade in local markets on the banks of the Nile. These merchants were apparently permitted to trade in Egypt (to export their oil and wine, as well as the all-important silver for everyday economic traffic)—perhaps after the payment of customs.

Trade with Nubia and Africa

The country most accessible from Egypt was Nubia, in present-day southern Egypt and Sudan. The ancient Egyptians obtained gold from Nubia beginning in the Middle Kingdom. Gold was called “ nub” in ancient Egypt and may be the source of the name Nubia. Ebony, ivory, leopard skins and incenses also came from Nubia, perhaps originating further south in Africa. Among the products that came from Africa were precious stones, cheetah -skins, ostrich-feathers and ostrich-eggs, monkeys, panthers, giraffes, dogs, and cattle. Many of them came via Nubia.

The natural political boundary between Egypt and Nubia was the first cataract of the Nile. Here the island of Elephantine became the place of mart, where the Nubians exchanged the productions of their own country, and the goods that they had obtained from tribes further to the south, for Egyptian products. Panther skins, monkeys, ebony, but above all ivory, were brought here to be imported into Egypt. Even the names of the two places at the frontier, 'Abu (Elephantine) and Suenet (Aswan), which signify ivory island and commerce, bear witness to the importance of this ancient trade. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Even under King Pepi, the African countries of 'Ert'et (Eritrea), Med'a, 'Emam (maybe Oman), Uauat, Kaau (maybe Kenya), and Tat'e'am were obliged to reinforce the Egyptian army with mercenaries. Under MerenRa, also the successor of Pepi, the princes of the countries 'Ert'et, Uauat, 'Emam, and Med'a brought supplies of acacia wood to Elephantine for Egyptian shipbuilding. On the other hand, the same inscription which gives us this account, expressly emphasises the fact as really extraordinary that a large expedition sent by MerenRa to the quarries of Aswan was escorted by one warship only — the Egyptians evidently did not feel quite safe from attacks at the frontier. Moreover, Elephantine itself was originally in the possession of Nubian princes, though even in early times they naturalised themselves as Egyptian officials and vassals of the Pharaohs; the most ancient of their tombs, belonging perhaps to the 6th dynasty, shows that the governor of that time was a dark brown Nubian, though his court seems to have been purely Egyptian.

The mighty kings of the 12th dynasty penetrated farther into Nubia, and completely opened out the northern part of that country to Egyptian civilization. Senusret I subjected the south as far as the “ends of the earth," doubtless with the principal object of gaining access to the gold mines of the Nubian desert; and under his reign we hear for the first time of the “miserable Nubia," such as of the southern part of Nubia. Nevertheless, it was only the northernmost part of his conquest, the country of Uauat, that he was able to retain and to colonise, or as the Egyptians said, to provide with monuments; his great-grandson, Senusret III, was the first to achieve more. The latter extended his “southern frontier “as far as the modern Semneh, and boasted that “he had pushed forward his boundaries further than those of his fathers, and had added an increase to that which he had inherited. " ''' In the eighth year of his reign he established the frontier stone there, “so that no African might pass it, neither by water nor by land, neither with boats nor with herds of the African. " Those Africans only who came as ambassadors, and those who were traveling to the market of 'Eqen (this must have been the frontier station) were excepted, and free passage was allowed to them, though not on their own boats. "

.jpg)

trade of leopard skins

Trading Wood in the Levant

The ancient Egyptians traded for cedar from Byblos (present-day Lebanon). Boats from Byblos hugged the Mediterranean coast and traveled up the Nile.

Steve Vinson of Indiana University wrote: “The transport of large quantities of wood, especially from western Asia, is documented from an early period in Egypt; much, if not all, of this cargo must have been transported by sea. Imported wood was used in a number of First Dynasty royal tombs, and a First Dynasty label from the tomb of Aha associates an image of a ship with the word mr, although it is not clear whether the reference here is to the vessel’s construction or its cargo. From the Fourth Dynasty (reign of Seneferu), the Palermo Stone records a shipment of some 40 ships loaded with coniferous wood. [Source: Steve Vinson, Indiana University, Bloomington, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2013, escholarship.org ]

“More details of the procedures by which the long, straight timbers available from the area of Lebanon and Syria were transported to Egypt come from the New Kingdom, when battle reliefs of Sety I at Karnak show foreign princes cutting down trees for transport back to Egypt, while others, possibly lower-status individuals, lower the trees with cables attached to the upper branches. From the Third Intermediate Period, the Report of Wenamun describes large tree-trunks being dragged down to the shore.

“Wenamun reports that a limited number of wooden ship components were placed aboard a transport ship bound for Egypt as a preliminary, good-faith shipment, but aside from this, no Egyptian text or image describes the specific modalities of the actual sea- transport of large timber. One might compare a first-millennium B.C. Assyrian relief from the palace of Sargon at Khorsabad, which shows tree-trunks being towed behind Phoenician transport ships off the Syrian coast. Such towing may have been the (or a) method by which the Egyptians, or Western Asians in the service of Egypt, also moved cargoes of the largest trunks of wood back to Egypt.”

Syrian Products Imported by Ancient Egypt

The number of Syrian products imported into Egypt during the New Kingdom when had stable relations with the Hittites was immense. If we were to judge of these imports by the pictures in the Egyptian tombs alone, we should obtain very false ideas; these pictures seem to imply that the Egyptians had no need of any of the products of Mesopotamia or Syria except those that are constantly repeated in the representations — splendid silver and gold vessels, precious stones, horses, and a few rare animals such as bears and elephants. But fortunately we learn the true state of things from the literature of the 19th and 20th dynasties; ' and when we come to consider this literature, we almost feel inclined to maintain that really there was scarcely anything that the Egyptians of this period did not import from Syria. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Amongst the imports listed on one document aee:

Carriages: together with their manifold accessories,

Weapons: the sword hurpu (mn), the lance and quiver

Sticks and puga;

Musical instruments: lyre the flutes

Vessels, etc. for beer, the yenra of silver, the sack,

Liquids: the drinks yenbu, the beer of Oede, the wine of Charu, and “much oil of the harbour ";

Bread, such as that oit'urufe (no); other kinds of bread, Kamhu (nop), 'Ebashtu and Kerashtu; Arupusa bread and “various Syrian breads ";

Incense

Fish:

Cattle: horses from Sangar, cows from 'Ersa, bulls (ebary) from Hittites,

It is interesting to note in connection with the development of the trade by sea, one rich man spoken of possesses his own ship, to bring his treasures from Syria. The foreign products may often be recognised by their foreign names (which moreover are not all of them Semitic); there are however certain articles, which though doubtless imports (as cattle, beer, wine), do not bear foreign names.

Trade with Punt

Punt, a mysterious fabled land south of Egypt, supplied Egypt with myrrh, ebony, ivory, gold, spices, panther skins, live baboons and other exotic animals and frankincense. The exact location of Punt is still unknown. It may have been in modern-day Somalia, Yemen or Oman. Traders crossed the Eastern desert and sailed from the Red Sea to get there. Much of what is known about Punt is based on reliefs found on the wall of the Deir el Bahri temple, built around 1490 B.C. in western Thebes. The reliefs show trade between rulers of Punt and emissaries of Queen Hatshepsut.

The ancient Egyptians called Punt the “Divine Land” or the “Land of Gods”. It was considered of old by the Egyptians as the original source of incense and other precious things. Not to much should be attached to the names as they were general terms created by commerce, such as the word Levant of modern times. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

There were stories related to Punt about ants or griffins seeking gold in the desert and gigantic birds collecting precious stones in the nests they have built high up in the mighty mountains. It was said that even ivory could not possibly have been obtained from the prosaic elephant, it must be the horn of the noble unicorn. The spices and essences must come from wonderful islands lying far away in the ocean; there the sailors find them at certain times lying on the strand, guarded only by spirits or by snakes. The air is so heavy with the fragrance that they emit, that it is necessary to burn asafoetida (a gum from a variety of giant fennel) and goat's hair to counteract the excess of sweet scents.

See Separate Article: PUNT AND THE INCENSE COUNTRIES africame.factsanddetails.com

Queen's Bracelets Contain Earliest Evidence of Egypt-Greek Trade

Bracelets found in the tomb of the ancient Egyptian queen Hetepheres I — the mother of Khufu, the builder of the Great Pyramid of Giza — reveals information about the trade networks that once linked the Old Kingdom to Greece. Jennifer Nalewicki wrote in Live Science: After analyzing samples taken from the jewelry, an international team of archaeologists determined that the bracelets contained copper, gold and lead. There were also inlays made using semiprecious gemstones such as turquoise, lapis lazuli and carnelian, which were common features in ancient Egyptian jewelry, according to a statement. [Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, June 2, 2023]

However, the pieces, including one depicting a butterfly, also contained traces of silver, despite there not being any known local sources of the precious metal in ancient Egypt in 2600 B.C., when the items were crafted. The team looked at the ratio of isotopes — atoms that have different numbers of neutrons than usual in their nuclei — in the lead. Based on this analysis, the researchers determined that the materials were "consistent with ores from the Cyclades," a group of Greek islands in the Aegean Sea, as well as with those from Lavrion, a town in southern Greece, according to a study published in the June issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

"The origin of silver used for [artifacts] during the third millennium has remained a mystery until now," lead author Karin Sowada, a lecturer in the Department of History and Archaeology at Macquarie University in Sydney, said in the statement. "This new finding demonstrates, for the first time, the potential geographical extent of trade networks used by the Egyptian state during the early Old Kingdom at the height of the Pyramid-building age. "

It's likely that the silver came through the port of Byblos in what is now Lebanon, said the researchers, who noted that Byblos tombs from the late fourth millennium have many silver objects and that there was activity between this port and Egypt at the time. The silver on the bracelets is the first evidence of long-distance exchange between Egypt and Greece, they added.

The study also provides insight into how the bracelets were forged. "The bracelets were made by hammering cold-worked metal with frequent annealing [a heating process] to prevent breakage," study co-author Damian Gore, a professor in the School of Natural Sciences at Macquarie University, said in the statement. "The bracelets were also likely to have been alloyed with gold to improve their appearance and ability to be shaped during manufacture. "

Queen Hetepheres I was one of ancient Egypt's most influential queens; she was the wife of Sneferu, the first pharaoh of the fourth dynasty (circa 2575 B.C. to 2465 B.C.). Her tomb, discovered at Giza in 1925, held many treasures, such as gilded furniture, gold vessels and jewelry, including 20 of these bracelets, the researchers wrote in the study. Some of the bracelets are currently part of the collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024