ANCIENT EGYPTIAN ECONOMY

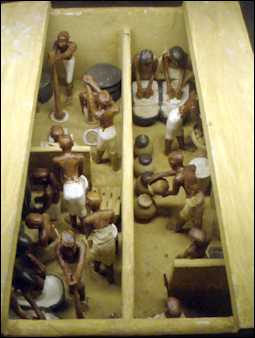

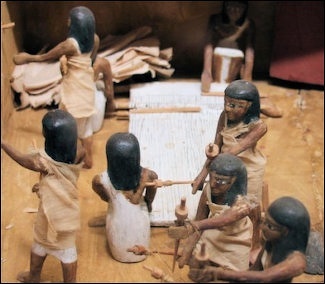

Bakery and brewery The Egyptian economy in the time of the pyramids was powered the by the construction of the pyramids. Pyramids building required labor. An economy was necessary to pay them. Later, there were two types of banks operating within Egypt, royal and private.

Ben Haring of Universiteit Leiden wrote: “The principal production and revenues of Egyptian society as a whole and of its individual members was agrarian, and as such, dependent on the yearly rising and receding of the Nile. Most agricultural producers were probably self-sufficient tenant farmers who worked the fields owned by wealthy individuals or state and temple estates. In addition to these, there were institutional and corvée workforces, and slaves, but the relative importance of these groups for society as a whole is difficult to assess. According to textual evidence, crafts were in the hands of institutional workforces, but indications also exist of craftsmen working for private contractors. [Source: Ben Haring, Universiteit Leiden, Netherlands, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

Trade was essentially barter with reference to fixed units of textile, grain, copper, silver, and gold as measures of value. Coins were imported and produced in the Late Period, but a system close to a monetary economy is attested only from the Ptolemaic Period onward. Marketplaces were frequented by private individuals (including women) as well as professional traders, both native and foreign. Imports were secured by conquests and military control in the Levant, from which silver, oil, and wine reached Egypt, and in Nubia, rich in its deposits of gold.

See Separate Article: MONEY, BARTER AND RATIONING IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com Also See Separate Articles on LABOR, TRADE, AGRICULTURE, LIVESTOCK, RESOURCES AND MINING at africame.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Ancient Egyptian Economy: 3000–30 BCE” by Brian Muhs (2018) Amazon.com;

“Commerce and Economy in Ancient Egypt” by Andras Hudecz (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Economy of Ancient Egypt: State, Administration, Institutions”

by Mahmoud Ezzamel (2024) Amazon.com;

"Domain of Pharaoh: the Structure and Components of the Economy of Old Kingdom Egypt" by Hratch Papazian Amazon.com;

“Ancient Economy” by M. I. Finley (1912-1986) and Ian Morris (1999) Amazon.com;

“Labour Organisation in Middle Kingdom Egypt, Illustrated, by Micòl Di Teodoro (2018) Amazon.com;

“Economic Life at the Dawn of History in Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt: The Birth of Market Economy in the Third and Early Second Millennia BCE” by Refael (Rafi) Benvenisti and Naftali Greenwood (2024) Amazon.com;

“From Egypt to Mesopotamia: A Study of Predynastic Trade Routes” by Samuel Mark (1997) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Near East: History, Society and Economy”

by Mario Liverani (2014) Amazon.com;

“Archaic Bookkeeping: Early Writing and Techniques of Economic Administration in the Ancient Near East” by Hans J. Nissen, Peter Damerow, Robert K. Englund (Author), Amazon.com;

“State in Ancient Egypt, The: Power, Challenges and Dynamics” by Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia (2019) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization” by Barry Kemp (1989, 2018) Amazon.com;

Economic Activity In Ancient Egypt

Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia of the CNRS in France wrote: Specialized, large-scale workshops aiming to supply the army, temples, and the palace coexisted with a more modest but widespread artisan production, in the hands of craftsmen (potters, leather workers, weavers, brick makers, etc.) who were often the object of mockery i n the satire-of-trades texts. Finally, the supplying of cities with charcoal, fresh vegetables, meat, and fish is occasionally referred to in administrative documents and private letters, thus giving an idea of the impact of urban markets on the economic activities, trades, and lifestyles of people living far away from cities. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia, Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“That fishermen, for instance, were paid in silver and, in turn, paid their taxes in silver during the reign of Ramesses II, suggests t hat markets (and traders) played an important role in the commercialization of fish, harvests, and goods, in the use of precious metals as a means of exchange, and in the circulation of commodities. Credit is also evoked in the textual record and it can be posited that, at least in some cases, it stimulated the output of various crafts, particularly in domains such as textile production in the domestic sphere. While in some instances women delivered pieces of cloth on a compulsory basis, it is possible that, in other instances, they produced textiles for markets through the mediation of traders. Individuals also provided loans and credit to their neighbors, thus creating a network of personal bonds and dependence that reinforced their local preeminence as well as the accumulation of wealth in their hands.

Natural Resources in Ancient Egypt

Diorite limestone and granite were two of the most important resources. They were used to build temples and monuments and were of such importance quarrying them was controlled by a government monopoly. Limestone was mined at sites near Memphis, Amarna and Abydos. Granite, diorite and sandstone were mined primarily around Aswan.

Flint, stone, copper, feldspar, amesyth, jasper, agate, turquoise, Egyptian alabaster, and malachite were mined and quarried from sites mostly in Eastern Desert, the Sinai and around the Red Sea. Nubia was a major source of gold and exotic materials. Valuable obsidian came from Ethiopia. Egyptians may have used amber in mummification because its is a powerful desiccant (or drying agent).

The main resource that Egypt had to trade was gold. An envious Assyrian king wrote: “Gold in your country is dirt: “one simply gathers it up.” The mines that ancient Egyptians used to get gold, emeralds and silver are all depleted now. Imports were secured by conquests and military control in the Levant, from which silver, oil, and wine reached Egypt, and in Nubia, rich in its deposits of gold.

Iron was made around 1500 B.C. by the Hitittes. About 1400 B.C., the Chalbyes, a subject tribe of the Hitittes invented the cementation process to make iron stronger. The iron was hammered and heated in contact with charcoal. The carbon absorbed from the charcoal made the iron harder and stronger. The smelting temperature was increased by using more sophisticated bellows. About 1200 BC, scholars suggest, cultures other than the Hittites began to possess iron. The Assyrians began using iron weapons and armor in Mesopotamia around that time with deadly results, but the Egyptians did not utilize the metal until the later pharaohs.

Markets in Ancient Egypt

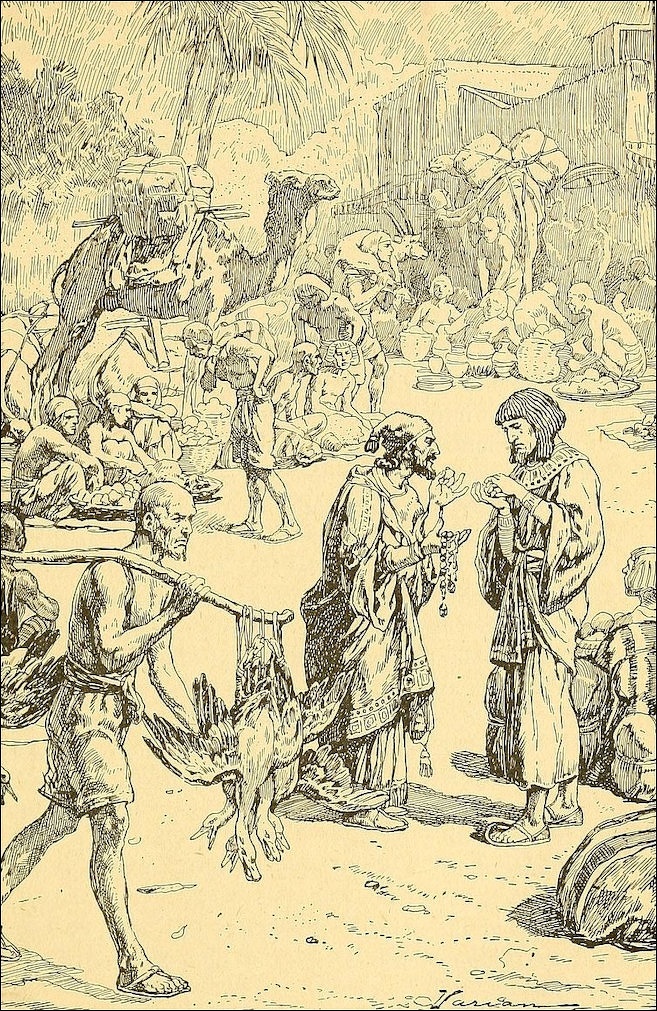

Ben Haring of Universiteit Leiden wrote: “Texts and tomb scenes testify to the existence of marketplaces where movables changed hands. The Egyptian word for river bank (mryt) is often used with the meaning “marketplace,” and tomb scenes confirm that such places were indeed located at the river. The booths depicted in the scenes accommodate men as well as women. The latter could engage in local trade, probably as sellers of surplus produce of the household, especially textiles. (Linen) textiles were actually a common means of payment, very much like grain, copper, and silver, and are documented as such in the exchange of movables and real estate from the Old Kingdom onward. [Source: Ben Haring, Universiteit Leiden, Netherlands, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

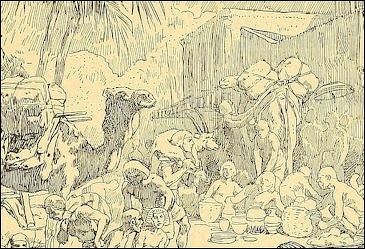

The remarkable pictures in a tomb at Saqqara show us the scenes of daily life in a market of the time of the Old Kingdom; they represent a market such as would be held on the estate of a great lord for his servants and his peasants. The fish-dealer is sitting before his rush basket, he is busy at this moment in cleaning a great sheath-fish, while he haggles about the price with his customer. The latter carries her objects for barter in a box, and is very far from being silent — she is holding a long conversation with the salesman as to how much she “will give for it. " Near this group another tradesman is offering ointment or something similar for sale. Another is selling some objects that look like white cakes; the collarette which is offered him for one of these does not seem to him to be enough. “There (take) the sandals (as well)," says the buyer, andthus the bargain is brought at last to a conclusion. Brisk business is being carried on round the greengrocer. One customer is buying vegetables in exchange for a necklet, and the dealer assures him: “See I give the (full) value”; another customer comes up at the same moment, in the hope of buying his meal of onions in exchange for a fan. Vegetables, however, are not the only things sold here; there is another dealer squatting before his basket of red and blue ornaments, he is bargaining with a woman who wants to buy one of his bright strings of beads. By her side is a man with fish hooks (?) who seems to be vainly pressing his wares on another man standing by.

Juan Carlos Moreno García wrote: In some instances urban markets, business, and traders were the objects of praise New Kingdom compositions. Of the Ramesside capital Pi-Ramesse, for example, it was written: “Pleasant is the market-place with/because of (?) its money there, namely the vine tendrils (?) and business. The chiefs of every foreign country come in order to descend with their products” (ostracon). [Source Juan Carlos Moreno García, University of Paris IV-Sorbonne, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2018; escholarship.org ]

There the quays were bursting with the business of foreign and Egyptian traders, and with women selling their products, while officials oversaw the arrival of cargo-laden ships and the activities that took place in the harbor areas (as we learn from Sarenput I, governor of Aswan in the early Middle Kingdom and superior of the harbor areas of Elephantine). Urban and rural markets were places where people exchanged products and news, frequented by peddlers from remote areas (such as the famous Eloquent Peasant, who came with his small caravan of donkeys from Wadi Natrun to Heracleopolis to trade), while small exchanges of gifts between neighbors cemented social relations within communities.

Merchants and Traders in Ancient Egypt

Marketplaces were frequented by private individuals (including women) as well as professional traders, both native and foreign. A poem of very ancient date tells us in fact of tradesmen who were neither the serfs of high lords, nor officials of the state, but who worked for their own living. One is said to travel through the Delta “in order to earn wages," another, a barber, goes from street to street to pick up news, a third, a maker of weapons, buys a donkey and sets forth for foreign parts to sell his wares. In the same poem we read that the weaver must always sit at home at his work, and if he wishes to get a little fresh air, he must bribe the porter; we see therefore that the poet considers him to be a bondservant. ' [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Ben Haring of Universiteit Leiden wrote: “Trade in an institutional context seems to have been limited to men. The Egyptian word Swtj means “trader,” but not necessarily “merchant”. Bearers of this title worked for temples and for the households of wealthy individuals, their task being to exchange the surplus production of these households (e.g., textiles) for other items, such as oil and metals. Such trade ventures are recorded in ship’s logs from the Ramesside Period. Although attested in institutional contexts only, traders may well have used their position and skills to engage in transactions for their own profit, as did institutional craftsmen (see Labor). [Source: Ben Haring, Universiteit Leiden, Netherlands, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

Government Control in the Ancient Egyptian Economy

Toby Wilkinson wrote in “The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt”, “Ideology is never enough, on its own, to guarantee power. To be successful over the long term, a regime must also exercise effective economic control to reinforce its claims of legitimacy. Governments seek to manipulate livelihoods as well as lives. The development in ancient Egypt of a truly national administration was one of the major accomplishments of the First to Third dynasties, the four- hundred- year formative phase of pharaonic civilization known as the Early Dynastic Period (2950-2575). At the start of the period, the country had only just been unified. Narmer and his immediate successors were faced with the challenge of ruling a vast realm, stretching five hundred miles from the heart of Africa to the shores of the Mediterranean. By the close of the Early Dynastic Period, the government presided over a centrally controlled command economy, financing royal building projects on a lavish scale. Just how this was achieved is a story of determination, innovation, and, above all, ambition..[Source: Excerpt “The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson, Random House, 2011, from the New York Times, March 28, 2011 ]

"The government’s ambition to control every aspect of the national economy is underlined by two measures introduced in the First Dynasty. Both are attested on the Palermo Stone, a fragment of royal annals that were compiled in the Fifth Dynasty, around 2400, and stretched back to the beginning of recorded history. The earliest surviving entry, for a First Dynasty king, probably Narmer’s immediate successor, Aha, concerns an event called the “Following of Horus,” which evidently took place every two years. Most probably, it consisted of a journey by the king and his court along the Nile Valley. In common with the royal progresses of Tudor England, it would have served several purposes at once. It allowed the monarch to be a visible presence in the life of his subjects; enabled his officials to keep a close eye on everything that was happening in the country at large, implementing policies, resolving disputes, and dispensing justice; defrayed the costs of maintaining the court, and removed the burden of supporting it year- round in one location; and, last but by no means least, facilitated the systematic assessment and levying of taxes. (A little later, in the Second Dynasty, the court explicitly recognized the actuarial potential of the Following of Horus. Thereafter, the event was combined with a formal census of the country’s agricultural wealth.) From the third reign of the First Dynasty, the Palermo Stone also records the height of the annual Nile inundation, measured in cubits and fractions of a cubit (one ancient Egyptian cubit equals 20.6 inches). The reason why the court would have wished to measure and archive this information every year is simple: the height of the inundation directly affected the level of agricultural yield the following season, and would therefore have allowed the royal treasury to determine the appropriate level of taxation.

beer making

"Under state sponsorship, Egypt’s international relations entered a new period of dynamism — not that you would have guessed it from the official propaganda. For domestic consumption, the Egyptian government maintained a fiction of splendid isolation. According to royal doctrine, the king’s role as defender of Egypt (and the whole of creation) involved the corresponding defeat of Egypt’s neighbors (who stood for chaos). To instill and foster a sense of national identity, it suited the ruling elite — as leaders have discovered throughout history — to cast all foreigners as the enemy. An ivory label from the tomb of Narmer shows a Palestinian dignitary stooping in homage before the Egyptian king. At the same time, in the real world, Egypt and Palestine were busy engaging in trade. The xenophobic ideology masked the practical reality. This should serve as a warning for the historian of ancient Egypt: from earliest times, the Egyptians were adept at recording things as they wished them to be seen, not as they actually were. The written record, though undoubtedly helpful, needs careful sifting, and must always be weighed against the unvarnished evidence dug up by the archaeologist’s trowel.

"Whereas Egypt’s relationship with the Near East was, from the start, contradictory and complex, its attitude toward Nubia — the Nile Valley south of the first cataract — was far more straightforward . . . and domineering. Before the beginning of the First Dynasty, when the predynastic kingdoms of Tjeni, Nubt, and Nekhen were rising to prominence in Egypt, a similar process was under way in lower (northern) Nubia, centered on the sites of Seyala and Qustul. With a sophisticated culture, kingly burials, and trade with neighboring lands, including Egypt, lower Nubia displayed all the hallmarks of an incipient civilization. Yet it was not to be. The written and archaeological evidence tell the same story, one of Egyptian conquest and subjugation. Egypt’s early rulers, in their determination to acquire control of trade routes and to eliminate all opposition, moved swiftly to snuff out their Nubian rivals before they could pose a real threat.

"The inscription at Gebel Sheikh Suleiman which shows a giant scorpion holding in its pincers a defeated Nubian chieftain, is a graphic illustration of Egyptian policy toward Nubia. A second inscription nearby, dating to the threshold of the First Dynasty, completes the story. It shows a scene of devastation, with Nubians lying dead and dying, watched over by the cipher (hieroglyphic marker) of the Egyptian king. The prosperous city- states of the Near East, which were useful trading partners and geographically separate from Egypt, could be allowed to exist, but a rival kingdom immediately upstream was unthinkable. Following Egypt’s decisive early intervention in lower Nubia, this stretch of the Nile Valley — though it would remain a thorn in Egypt’s side — would not rise again as a serious power for nearly a thousand years.

"Secure in its borders, with hegemony over the Nile Valley and flourishing trade links, the early Egyptian state witnessed a marked rise in overall prosperity, but the rewards were not evenly spread across the population. Cemeteries that span the period of state formation show a sudden polarization of grave size and wealth, a widening gap between rich and poor, with those who were already affluent benefiting the most. The greatest beneficiary by far was the state itself, for the practical effect of political unification was to convey all land into royal ownership. While individuals and communities continued to farm their land as they had before, they now found themselves with a landlord who expected rent in return for their use of his property.

Writing and Economics in Ancient Egypt

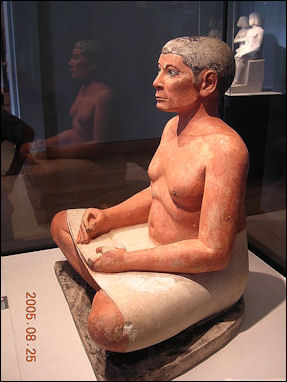

scribe statue Toby Wilkinson wrote in “The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt”, “Among the great inventions of human history, writing has a special place. Its transformative power — in the transmission of knowledge, the exercise of power, and the recording of history itself — cannot be overstated. Today, it is virtually impossible to imagine a world without written communication. For ancient Egypt, it must have been a revelation. We are unlikely ever to know exactly how, when, and where hieroglyphics were first developed, but the evidence increasingly points toward a deliberate act of invention. The earliest Egyptian writing discovered to date is on bone labels from a predynastic tomb at Abdju, the burial of a ruler who lived around 150 years before Narmer. These short inscriptions already used fully formed signs, and the writing system itself showed the complexity that would characterize hieroglyphics for the next three and a half thousand years. Archaeologists dispute whether Egypt or Mesopotamia should take the credit for inventing the very idea of writing, but Mesopotamia, especially the southern city of Uruk (modern Warka), seems to have the better claim. Excerpt “The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson, Random House, 2011, from the New York Times, March 28, 2011 ]

"It is likely that the idea of writing came to Egypt along with a raft of other Mesopotamian influences in the centuries before unification — the concept, but not the writing system itself. Hieroglyphics are so perfectly suited to the ancient Egyptian language, and the individual signs so obviously reflected the Egyptians’ particular environment, that they must represent an indigenous development. We may imagine an inspired genius at the court of one of Egypt’s predynastic rulers pondering the strange signs on imported objects from Mesopotamia — pondering them and their evident use as encoders of information, and devising a corresponding system for the Egyptian language. This may seem farfetched, but the invention of the Korean script (by King Sejong and his advisers in a.d. 1443) provides a more recent parallel, and there are few other entirely convincing explanations for the sudden appearance of fully fledged hieroglyphic writing.

Whatever the circumstances of its invention, writing was swiftly embraced by Egypt’s early rulers, who recognized its potential, not least for economic management. In the context of competing kingdoms expanding their spheres of influence, the ability to record the ownership of goods and to communicate this information to others was a marvelous innovation. Straightaway, supplies entering and leaving the royal treasury began to be stamped with the king’s cipher (his Horus name). Other consignments, destined for his tomb, had labels attached to them, recording not just ownership but other important details such as contents, quantity, quality, and provenance. Having been developed as an accounting tool, writing found an enthusiastic reception among bureaucratically minded Egyptians. Throughout ancient Egyptian history, literacy was reserved for a tiny elite at the heart of government. To be a scribe — to be able to read and write — was to have access to the levers of power. That association was evidently formed at the very start.

"Writing certainly transformed the business of international trade. Many of the labels from the royal tombs at Abdju — whose miniature scenes of royal ritual serve as an important source for early pharaonic culture — were originally attached to jars of high quality oil, imported from the Near East. An upsurge in such imports during the First Dynasty can be associated with the establishment of Egyptian outposts and trading stations throughout southern Palestine. At sites such as Nahal Tillah and Tel Erani in present- day Israel, imported Egyptian pottery (some stamped with the cipher of Narmer), locally made pottery in an Egyptian style, and seal impressions with hieroglyphs testify to the presence of Egyptian officials in the heart of the oil- and wineproducing region. At the springs of En Besor, near modern Gaza, the Egyptian court established its own supply center, for revictualing trade caravans using the coastal route between Palestine and the Nile delta.

Ancient Egypt’s Barter- and Ration-Based, Mixed Economy

Documentation from the New Kingdom, mainly in form of government records and administrative texts indicates that ancient Egypt enjoyed had a barter- and ration-based, “mixed economy.” Sally Katary of Laurentian University in Ontario wrote: “The economic system fostered a complex system of economic interdependency wherein market forces played a complementary role: thus it was a “mixed” rather than a redistributive economy.” [Source: Sally Katary, Laurentian University of Sudbury, Ontario, Canada, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2011, escholarship.org ]

“The Egyptians engaged in barter or “money-barter,” the latter representing “an intermediate stage in the progress from a barter economy to a money economy…a stage in a theoretically evolutionary development”. While there is some evidence that taxes might have been paid in gold and silver (among other commodities) by towns and villages and gold occurs in official texts most often in association with officials at the southern frontier, this was not the case with ordinary individuals. Taxes in “money” were unknown until the Third Intermediate Period.”

Hana Vymazalova, a Czech Egyptologist, wrote: “ “Rations (compensation in the form of food or provisions) constituted the basis of the redistribution economy of the ancient Egyptian state and are usually understood as payment given in return for work. The Egyptian evidence shows no clear difference between the rations of laborers and the wages of personnel hired to perform services for projects organized by, or connected to, the state. It has therefore been suggested that rations and wages occasionally merged. Rations were a component of royal projects of all kinds, including, for example, the construction of funerary complexes, the maintenance of the cults of deceased rulers, the perpetuation of the cults of temple deities, military expeditions, expeditions to quarries, and agricultural work. They were also employed in the private sphere as payment for those who worked, for instance, on an estate or on projects organized by non-royal individuals. Rations were applied to both the work force of laborers and to the officials who supervised them.” [Source: Hana Vymazalova, a Czech Egyptologist, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

See Separate Article: MONEY, BARTER AND RATIONING IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Temple Business Contracts in Ancient Egypt

Examples of trade contracts can be seen in texts from Prince Hepdefae from the Middle Kingdom province of Asyut. These contracts were written on papyrus and show how it was possible to carry on complicated commercial transactions with these basic conditions of payment. This prince desired that in the future priests of his nome, with of course indemnification for cost, should present certain small offerings to his temple. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

Under complicated conditions he made over a certain fund to the temple, the yearly interest of which would cover the really small cost of bread loaves and lamp-wicks. Hepdefae had recourse to a rather peculiar procedure. On one hand he ceded parts of his fields, thus, he gave a piece of land to a priest of Anubis for the yearly supply of three wicks. On the other hand he bequeathed parts of his revenues, the first-fruits of his harvest, or the feet of the legs of the bull which belonged to him and his successors out of the sacrifices; but above all he preferred to pay with the revenues which he drew as member of a priestly family from the emoluments of the 'Epuat temple, the so-called “days of the temple. "

These daily rations, however, which consisted of provisions of all kinds, could not be received by people who lived at a distance from the temple; he was therefore obliged, if he wished to use them as payment for these people, to have recourse to a system of exchange; thus he gave up 22 "days of the temple" to his colleagues in exchange for a yearly supply of 2200 loaves and 22 jugs of beer to be given to those persons whom he really wanted to pay. In this way he exchanged those revenues of the temple, that were unsuitable to serve as payments, into bread and beer, which he could hand over to any one.

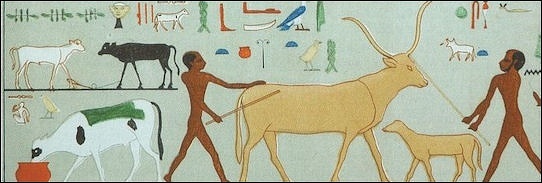

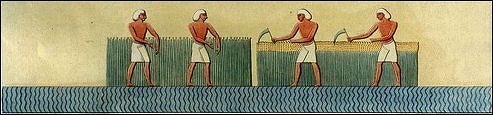

Agrarian Production in Ancient Egypt

Ben Haring of Universiteit Leiden wrote: “There can be no doubt that production in ancient Egypt was first and foremost agrarian, the principal food crops being (emmer) wheat and barley, and the principal components of the Egyptian diet being bread and beer. Many of these and other crops were produced by tenant farmers, who were largely self- sufficient as far as the production of their own food was concerned. They lived in what anthropologists refer to as a peasant society (or peasant economy): a society mainly consisting of self-sufficient agrarian producers who pay part of their crops as tax to the government, or as rent to the owners of the land they cultivate. A variation of the peasant society, more specifically relevant to modern developing countries, is that of farmers who sell cash crops and subsequently are able to buy food. Such a strategy may occasionally be reflected in Egyptian sources—for example, in the Middle Kingdom Tale of the Eloquent Peasant, in which the “peasant” (sxtj), actually a hunter/gatherer from the Wadi el-Natrun oasis, intends to exchange his products (minerals, wild plants, animal skins) for grain on the market. [Source: Ben Haring, Universiteit Leiden, Netherlands, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“There is insufficient data to establish the amount of agrarian production (grain or otherwise) in ancient Egypt. Quantitative data are scarce and their chronological distribution is uneven. Estimates have been made, however, of the population and the total extent of fertile area during the Pharaonic and Greco-Roman periods. The figures usually quoted by Egyptologists are those arrived at by Butzer on the basis of geological surveys, as well as textual and archaeological data on ancient demography and agrarian technology. Butzer calculated a fertile area of 22,400 sq. kilometers. and a population of 2.9 million in the early Ramesside Period (about 1250 B.C.), and 27,300 sq. kilometers. with a population of 4.9 million in the Ptolemaic Period (about 150 B.C.). The underlying assumption is that 130 persons could live from the production of one square kilometer in the former, and 180 in the latter period. Their food would basically include wheat and barley, vegetables, dates, and fish, and for the well-to-do the diet would include meat and fruit. The increase in agrarian production per square kilometer in the Greco-Roman Period can be explained by improvements in agricultural technology (irrigation devices, new crops), and perhaps by a more efficient agrarian administration.

“Some documents provide data concerning grain production per square kilometer, although there remain uncertainties about the measures employed and the quality of the fields referred to. Administrative texts from the Ramesside Period (1295 - 1069 B.C.) suggest a norm of 2,700 to 2,900 liters per hectare (l/ha) for basin land—that is, fields of the best quality, submerged by the annual rise of the Nile in antiquity. (Conversion of liters to kilos is apparently a less than reliable process: references featuring the conversion display diverging estimates, in which the equivalent of one liter of grain varies between 0.512 and 0.705 kilos). The Ramesside quota match those found in records from early twentieth-century Egypt (varying between approximately 2,000 and 2,800 l/ha for wheat, and between 2,500 and 3,400 l/ha for barley). Less productive types of land were expected to yield three-quarters or half of these amounts. It is uncertain how much of the land available for agriculture was actually sown with wheat or barley, rather than vegetables, fruit trees, fodder for animals, or flax. It is assumed, however, that most of the basin land was used for cultivating grain crops.

“Ramesside sources inform us about the organization of agrarian production insofar as it is connected with temples and government departments. The personnel of these institutions were called ihuty (iHwtj; plural: iHwtjw). According to some texts, an ihuty was responsible for the yearly production of almost 16,000 liters of grain. For this he would have to work 5.5 to 6 hectares of basin land. The most important agrarian document of this period, Papyrus Wilbour, records even larger areas as the responsibility of an individual ihuty. Together, these sources suggest that the word ihuty refers to a supervisor rather than (or as well as) a member of the actual workforce. On a higher level, the ihuty were supervised by scribes, priests, or high state and temple officials.”

Land Tenure in Ancient Egypt

Sally Katary of Laurentian University wrote: “Land tenure describes the regime by means of which land is owned or possessed, whether by landholders, private owners, tenants, sub-lessees, or squatters. It embraces individual or group rights to occupy and/or use the land, the social relationships that may be identified among the rural population, and the converging influences of the local and central power structures. Features in the portrait of ancient Egyptian land tenure that may be traced over time in response to changing configurations of government include state and institutional landownership, private smallholdings, compulsory labor (corvée), cleruchies, leasing, and tenancy. Such documents as Papyrus Harris I, the Wilbour Papyrus, Papyrus Reinhardt, and the Ptolemaic Zenon and Menches archives provide evidence of various regimes of landholding, the status of the landholders, their relationship to the land, and the way in which the harvest was divided among cultivators, landowners, and the state. Ptolemaic leases and conveyances of land represent the perspective of individual landowners and tenants. [Source: Sally Katary, Laurentian University, Sudbury, Ontario, Canada, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2012, escholarship.org ]

“The division of Egypt into two distinct agricultural zones, the 700-km-long Nile Valley and the Delta, as well as the Fayum depression and the oases of the Western Desert, produced regional differences that caused considerable variation in the organization of agriculture and the character of land tenure throughout antiquity. The village-based peasant society worked the land under a multiplicity of land tenure regimes, from private smallholdings to large estates employing compulsory (corvée) labor or tenant farmers under the management of the elite, temples, or the Crown. However cultivation was organized, it was predicated on the idea that the successful exploitation of land was the source of extraordinary power and wealth and that reciprocity, the basis of feudalism, was the key to prosperity.

“Consistent features in the mosaic of land tenure were state and institutional landowners, private smallholders, corvée labor, and cleruchs, the importance of any single feature varying over time and from place to place in response to changing degrees of state control. Leasing and tenancy are also elements that pervade all periods with varying terms as revealed by surviving leases. The importance of smallholding is to be emphasized since even large estates consisted of small plots as the basic agricultural unit in a system characterized by competing claims for the harvest. However, the exact nature of private smallholding in Pharaonic Egypt is still under discussion as is clear from studies that explore local identity and solidarity in all periods, subject to regional variation; the conflict between strong assertions of central control in the capital and equally powerful assertions of regional individuality and independence in the rural countryside; and the dislocation of the villager and his representatives from the local elites. Land tenure was also affected by local variation in the natural ecology of the Nile Valley. Moreover, variations in the height of the Nile over the medium and long term directly affected the amount of land that could be farmed, the size of the population that could be supported, and the type of crops that could be sown.

“The alternation of periods of unity and fragmentation in the control of the land was a major determinant of the varieties of land tenure that came to characterize the ancient Egyptian economy. The disruption in the balance between strong central control and local assertions of independence that resulted in periods of general political fragmentation or “native revolts” had a powerful effect upon the agrarian regime, economy, and society.

“The state’s collection of revenues from cultivated land under various land tenure regimes is also an element of continuity since the resources of the land constituted the primary tax-base for the state. Cultivators of all types had to cope with the payment of harvest dues owing to the state under all economic conditions, from famine to prosperity. These revenues fall under the terms Smw and SAyt and perhaps other terms occurring in economic and administrative texts in reference to dues owing to the state from the fields of the rural countryside.”

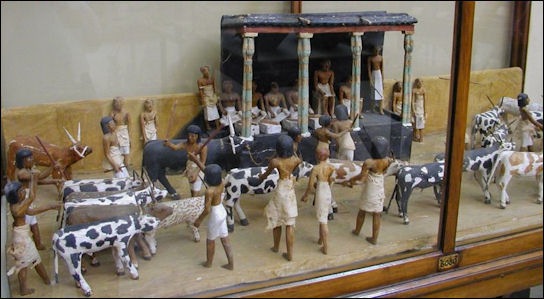

Estates in Old Kingdom (2649–2150 B.C.) Egypt

Juan Carlos Moreno García of Université Charles-de-Gaulle wrote: “Estates (also referred to as “domains”) formed the basis of institutional agriculture in Old Kingdom Egypt. Estates were primarily administered by the temples or by state agricultural centers scattered throughout the country, but were also granted to high officials as remuneration for their services. Sources from the third millennium B.C. show that estates constituted production networks where agricultural goods were produced, stored, and kept available for agents of the king who were traveling on state business. [Source: Juan Carlos Moreno García, Université Charles-de-Gaulle, France, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2008, escholarship.org ]

Estates were one of the main sources of income for the Egyptian state during the Old Kingdom. Most preserved sources concern the estates of institutions such as temples or the administrative centers known as Hwt (plural: Hwwt), or of certain state officials, including some members of the royal family. As estates were scattered all over the country, they constituted the links in a network of royal warehouses, production centers, and agricultural holdings that facilitated the production and storage of agricultural goods that were kept at the disposal of institutions or of the royal administration when needed.

“There is an important difference between Old Kingdom estates and their counterparts in later, better-documented periods: whereas texts like the Ramesside Wilbour Papyrus evoke thousands of estates directly controlled by the temples (the most important economic centers of the country from the New Kingdom on), third-millennium inscriptions show that royal centers founded by the king and administered by state-appointed officials controlled many estates and were, along with the temples, prominent places of institutional agricultural production.

“The most ancient sources concerning estates and their integration into the economic structure of the Egyptian state date from as early as the pre-unification period. Labels from the tombs of the late-Predynastic kings at Abydos appear to mention localities and estates that produced goods for, or sent goods to, the royal mortuary complexes. Hundreds of inscribed vessels from the 3rd-Dynasty pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara contain brief references to the officials and centers responsible for delivering offerings to Djoser’s funerary monuments and to those of his predecessors. These texts inform us that the Hwt (administrative center) and especially the Hwt- aAt (literally “great Hwt”—administrative center, probably larger than the Hwt), were the most important royal production units in the country. The existence of networks of this sort, in which royal estates produced goods collected at administrative centers and subsequently redistributed to other localities or officials, has recently come to light at Elephantine: hundreds of seal inscriptions, mainly dating to the 3rd Dynasty, record the delivery of goods from Abydos, the most important supra-regional administrative center in southern Egypt, to the local representatives and officials of the king in service at Elephantine. Slightly later sources, from the beginning of the 4th Dynasty, also evoke an economic and production geography in which royal administrative centers like the Hwt and Hwt-aAt governed smaller localities, estates, and fields, as was the case according to Metjen’s inscriptions: many titles borne by this official show that the Hwt and Hwt-aAt were the heads of territorial and economic units, sometimes referred to as pr (houses/estates; plural: prw), that encompassed many localities (njwt; plural: njwwt) located mainly in Lower Egypt.

“Therefore estates seem to have been firmly controlled by royal institutions and appear to have constituted the basic production units of the royal economy. The taxation and conscription of village inhabitants probably formed the other main source of income for the Pharaonic treasury, as the Gebelein papyri, from the end of the 4th Dynasty, show.

Estates composed a vital element in the economic and fiscal organization of the Egyptian state during the Old Kingdom. It should be emphasized that most estates depended on a network of royal centers (mainly Hwt) directly administered by royal officials—a feature that characterizes the Old Kingdom—whereas in later periods of Egyptian history the temples became the main holders of estates, which were therefore subject to a more indirect and fragile control by the king.”

Institutional and Private Interests in the Ancient Egyptian Economy

Ben Haring of Universiteit Leiden wrote: “The aforementioned documents also indicate that the institutional exploitation of one and the same plot of land often involved more than one party. Papyrus Valençay I, from the end of the 20th Dynasty (c. 1069 B.C.), gives a clear example of the institutions and individuals who owned plots and were liable to taxation. The text is a letter written by the mayor of Elephantine, who was being held responsible for the production of barley on a type of government estate, the khato (xA-tA), which, in this case, was incorporated into a Theban temple estate. A scribe of the latter institution came to collect the barley, but the mayor objected that the plot specified was not his responsibility. Instead, he argued, it was the property of some private individuals, and taxed as such by the royal treasury. The text thus shows the three types of landowners regularly mentioned in agrarian documents: royal, temple, and private. Papyrus Wilbour from the reign of Ramesses V (1147 - 1143 B.C.) is a lengthy register of institutional fields in Middle Egypt and the parties entitled to their production. Among the institutions are large urban and small provincial temples, and a select number of government departments, such as the royal treasury and harems. [Source: Ben Haring, Universiteit Leiden, Netherlands, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Basically, every institution had two types of agrarian domains. In the terms of Gardiner, these were: “non-apportioning” (presumably worked or supervised by the institution’s own personnel); and “apportioning,” or p(s)S (cultivated by other institutions or private individuals). The major part of the crops of apportioning fields was kept by the parties taking care of their cultivation, while a small part (varying between 7.5 percent and 15 percent) went to what Gardiner considered to be the owning institution. This institution, however, should rather be considered not as the “owner” but as having been entitled to tax received from the land (the percentage specified): apportioning fields were often in the hands of private individuals, who were the actual owners, and who yearly paid tax to the temple or government institution. This situation is also reflected in Papyrus Valençay I. The people cultivating their own land and paying their tax to the royal treasury are there called nmH(y) (plural: nmHyw), a word originally meaning “orphan,” but which in the New Kingdom had acquired the additional meaning “free” or “private,” and referred to people who owned property, but were not among the higher state and temple officials (sr; plural: srw; for this opposition see Römer 1994: 412 - 451). A similar status has been ascribed by Egyptologists to people called nDs (plural: nDsw), “small one,” in texts from the First Intermediate Period, and to the s n njwt tn “man of this town” of the Middle Kingdom, but this interpretation has been disputed. In the Greco- Roman Period, nmH(y) became the equivalent of the Greek eleutheros. The word is seldom used in Papyrus Wilbour, but it is likely that the individuals listed there as the holders of apportioning fields and as payers of taxes had precisely that status.

“On a lower level (with which the institutional documents were not concerned) were the actual cultivators, who may have been institutional workforces, private owners, or lessees. The latter (referred to in the previous section as tenant farmers) remain undocumented until the late Third Intermediate Period. By that time land leases had begun to appear as written contracts, a tradition that was continued in the Greco- Roman Period under the name misthosis. Documents from earlier periods occasionally refer to the practice, but the agreements themselves may have been oral ones. According to such contracts the lessee paid one fourth to as much as one half of the crop as rent. The contract also mentioned the harvest tax (Smw), about 10 percent of the crop, to be paid by the lessor to a temple or to the government, and it is tempting to regard the revenues from apportioning domains mentioned in Papyrus Wilbour as this very tax. Since many of the plots in this document belonged to apportioning domains, and most of these to private individuals, there must have been a great number of wealthy landowners in Egypt who could act as lessors. Furthermore, although land was remarkably cheap when compared with other modes of production (such as cattle and slaves), people who were not wealthy would not be inclined to buy it. It follows that very many of Egypt’s peasants probably leased the land they cultivated.

“A special case of shared interests in fields, the incorporation of crown land (khato) in the estates of other institutions, is illustrative of the complex interaction between temples and the government. Khato features prominently in Papyrus Wilbour and other agricultural documents. Plots of khato were included in the temples’ apportioning domains, which means that the temples received only minor shares of their revenues; the major part went to the khato-institution itself and was duly entered among its non-apportioning revenues. It is possible that the amount of khato land far exceeded the temples’ own non-apportioning domains, so that it formed a major part of their estates in terms of productive area, whereas the amount of grain the temples received from it was relatively low. Data from Papyrus Wilbour also suggest that the status of khato land could change: khato land incorporated in some other institution’s apportioning domain could, over the course of time, become autonomous, non- apportioning domains. These characteristics of khato help to explain the excessive proportions of some newly founded temple estates, as well as their reduction in later years.

“This example makes clear that the question of whether temples were economically independent or, rather, integrative parts of the government administration, is pointless. They were clearly separate institutions, but not fully autonomous, and their interests were closely connected with those of government departments and the crown. Their economic power was therefore not necessarily a threat to state interests at any moment in Pharaonic history. The king would have to consider, however, the interests of priests and temple administrators. From the Old Kingdom onwards, it was possible for him to exempt temple estates from taxation or compulsory labor (corvée) by decree. Such decrees were issued with respect to specific institutions and may therefore not represent a general policy. Government inspections of temples and their economic wealth are well attested for the Middle and New kingdoms; nation-wide temple inspections are known from the reigns of Amenemhat II, Tutankhamen, Merenptah, and Ramesses III.

“Apart from the inspections and certain fiscal aspects (such as khato), the temples appear to have been closed economic units. There are no indications that the temples’ wealth provided buffer stock for the population in times of food scarcity, despite suggestions to the contrary. Indeed the marginal contributions paid by the temples of western Thebes to the nearby community of necropolis workmen in the Ramesside Period, and their reluctance to assist when the latter’s food supply fell short, emphasize that temples did not normally play such a role.”

Egyptian peasants seized for not paying taxes

Taxes in Ancient Egypt

The Egyptians paid for their grand projects with stiff taxes. They kept meticulous records of who owed what and cracked down ruthlessly on those who didn't pay their share. Tomb paintings show clerks tallying up crops produced at harvest and making lists with a reed pen. They also show clerks monitoring beer breweries, slaughterhouses and workshops.

Tax collectors punished deadbeats by beating and flogging and torturing to death. Peasants were sometimes bound by their hands and feet and thrown into the irrigation ditches to drown. A tomb painting, dated around 2400 B.C., shows a tax official meeting with a group who hadn't paid their taxes. The next scene shows some of them being flogged.

Toby Wilkinson wrote in “The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt”, “The First Dynasty government lost no time in devising and imposing a nationwide system of taxation, to turn the country’s agricultural productivity to its own advantage. Once again, writing played a key role. From the very beginning of recorded history, the Egyptian government used written records to keep accounts of the nation’s wealth and to levy taxes. Some of the very earliest ink inscriptions — on pottery jars from the time of Narmer — refer to revenue received from Upper and Lower Egypt. It seems that, for greatest efficiency, the country was already divided into two halves for the purposes of taxation. . [Excerpt “The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson, Random House, 2011, from the New York Times, March 28, 2011 ]

See Separate Article: TAXES IN ANCIENT EGYPT: TYPES, HISTORY, COLLECTION, PUNISHMENTS africame.factsanddetails.com

Theories on the Ancient Egyptian Economy

Ben Haring of Universiteit Leiden wrote: “The economy of an ancient society—and one that is culturally very different from ours— such as Pharaonic Egypt is likely to display characteristics that do not have parallels in modern economies. Reconstructing such an ancient economy should therefore not exclusively proceed from modern economic observations and theories. Entirely devoid of preference for any specific theory is the important work by Wolfgang Helck, who arrived at his conclusions empirically, on the basis of extensive collections and a superb overview of ancient data. Helck argued that economic consciousness developed slowly in Egyptian history and that the development of this consciousness was hampered by the centralistic economy of the Old Kingdom; only from the First Intermediate Period onward would private individuals increasingly wrench themselves free from the all- embracing redistributive state. [Source: Ben Haring, Universiteit Leiden, Netherlands, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

“Janssen argued that characteristics of the ancient Egyptian mindset exhibited in religion and art, such as the (supposed) absence of individualism, would also apply to the economy. He saw the economic mind of the Egyptians as “realistic” rather than “abstract,” and little concerned with the motive of making profit. The character of the Egyptian economy as a whole he saw as mainly redistributive—that is, dominated by taxation and tributes. Janssen based his discussion on general characteristics of peasant economies worldwide. In doing so, he showed himself a proponent of a broader movement in economic history that had begun in the 1940s and was especially influential in economic anthropology. One source of its inspiration was the emergence of economies (in Eastern Europe and Asia) that were different from the “capitalist” market economies. Another was the anthropological interest in “primitive” economies. An early reflection of this movement in Egyptology was Siegfried Morenz’s study of conspicuous consumption.

“The main inspiration for this “substantivist” or “primitivist” movement was the economic historian Karl Polanyi. He and his followers (mainly anthropologists) argued that economy was not to be seen as an autonomous phenomenon (that is, as a self-regulating market), but as embedded in a political and social context. This embeddedness shows itself in three different ways (also called “patterns of integration”): exchange (in commerce), reciprocity (in social structures, such as kinship), and redistribution (in politic centralism). This train of thought became influential in historiography and in Near Eastern studies from the 1970s onwards. In Egyptology it found its clearest expression in Renate Müller-Wollermann’s discussion of trade in the Old Kingdom (1985). Authors discussing the nature of ancient Egyptian economy saw redistribution as its key feature (with or without specific reference to Polanyi: Bleiberg 1984, 1988; Janssen 1981). The Assyriologist and historian Mario Liverani used Polanyi’s theory to analyze international economic traffic as presented in Near Eastern sources (including the Egyptian) from the Late Bronze Age. Liverani reached the important conclusion that the “patterns of integration” did not determine the actual economic processes, but rather their ideological presentation in texts and monumental depictions.

“Others have voiced skepticism of, and even sharp protest against, the Polanyi-inspired view of ancient economics. The turning point in Egyptology was late in the 1980s, when more modernist views were brought forward, notably by Barry Kemp and Malte Römer. Kemp assumed that there was no lack of economic consciousness in ancient Egypt, given the political and social competition clearly evident in the ancient records. He also pointed out that a redistributionist government would never have been able to meet the demands of an entire population—moreover, not even those of its own institutions. It follows that any economy is a compromise between state dominance and self-regulating market, in which private demand is an important stimulus and sets prices. Nonetheless, discussions in the 1990s still very much focused on redistribution, state service, and the absence of individualism.

“The relative importance of government and market and the ways in which these were interrelated seems to dominate the present discussion of ancient Egyptian economy. David Warburton, partly inspired by the theories of John Maynard Keynes, concentrates on government concern with production and employment. An economist recently characterized the role of the state in the economy of ancient Egypt as a “risk consolidating institution”.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024