Home | Category: Government, Military and Justice

PHARAOHS

Amenhotep III Colossal Ancient Egypt’s ancient rulers are referred to today as "pharaohs," although in ancient times they each used a series of names as part of a royal titular. The word pharaoh originates from the Egyptian term "per-aa," which means "the Great House." The term was first incorporated into a royal title during the rule of Thutmose III (r. 1479-1425 B.C.). [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science June 2, 2023]

Susan Allen of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Pharaoh" is the Hebrew pronunciation of the ancient Egyptian term per-aa. Originally it referred to the royal estate, but came to be used for the king himself, just as we might say "The Palace" or "The White House." Each king upon his accession was known by five names, which formed his titulary. These were his Horus name, the Two Ladies name, the Gold Falcon name, his King of Upper and Lower Egypt name (throne name), and the Son of Re name, which was his personal name given at birth. The throne name and personal name are enclosed in a cartouche, or name ring, in inscriptions. Though the Nile valley and the Delta had been unified by the first rulers of Dynasty 1, this dual kingship of Upper and Lower Egypt was preserved in many aspects of kingship, including the two crowns of Egypt: the white crown of Upper Egypt and the red crown of Lower Egypt. Kings are depicted wearing either crown, as well as the merged double crown.” [Source: Susan Allen, Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

Pharonic dynasties were closely associated with their numbers. The pharaoh and their wives possessed both throne names and personal names. There were many Nefertitis, almost all queens. Many pharaohs married their sisters and daughters to keep the linage in the family. The longest reign of any ruler was 94 years of the Phiops II, a sixth dynasty pharaoh, who came to power in 2281 B.C. at the age of six.

The pharaohs, their families and their courts lived a fairly pampered existence. They were not required to all that much as they were look after by an after by an army of servants that included royal manicurists and royal hairdressers. Murder and kidnaping may have been practiced in the ancient Egyptians court. Based on the reading of hieroglyphics and way figures in tomb were erased and replaced with new ones, some scholars think that a vizier named Ihy, who lived around 2230 B.C., was killed by a mysterious outsider and married the daughter of King Unas and became King Teti, who in turn is believed to have been murdered by Ihy’s son who became Pepi I

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Pharaohs” by Joyce Tyldesley (2009) Amazon.com;

“Pharaohs: The Rulers of Ancient Egypt for Over 3000 Years” by Dr Phyllis G Jestice (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Pharaohs of Ancient Egypt” by Elizabeth Payne (1981) Amazon.com;

“The Great Book of Ancient Egypt: in the Realm of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass, Illustrated (2007, 2019) Amazon.com;

“The Pharaoh: Life at Court and On Campaign” by Garry J. Shaw (2012) Amazon.com;

“Lives of the Ancient Egyptians: Pharaohs, Queens, Courtiers and Commoners” by Toby Wilkinson (2007) Amazon.com;

”Private Lives of the Pharaohs: Unlocking the Secrets of Egyptian Royalty” by Joyce Tyldesley (2001) Amazon.com;

“Kingship, Power, and Legitimacy in Ancient Egypt: From the Old Kingdom to the Middle Kingdom” by Lisa K. Sabbahy (2004) Amazon.com;

"Domain of Pharaoh: the Structure and Components of the Economy of Old Kingdom Egypt" by Hratch Papazian Amazon.com;

“Judgement of the Pharaoh: Crime and Punishment in Ancient Egypt” by Joyce Tyldesley

Amazon.com;

“Chronicle of The Pharaohs” by Clayton Peter (1994) Amazon.com;

“The First Pharaohs: Their Lives and Afterlives” by Aidan Dodson (2021) Amazon.com;

“Abydos: Egypt's First Pharaohs and the Cult of Osiris” by David O'Connor (2009) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs” by Zahi Hawass (2005) Amazon.com;

“Tutankhamun: The Life and Death of a Pharaoh” by David Hamilton Murdoch Amazon.com;

"Ramesses II, Egypt's Ultimate Pharaoh" by Peter Brand Amazon.com;

“Chronicle of a Pharaoh: The Intimate Life of Amenhotep III” by Joann Fletcher (2000) Amazon.com;

“Warrior Pharaoh: A Chronicle Of The Life And Deeds Of Thutmose III, Great Lion Of Egypt, Told In His Own Words To Thaneni The Scribe”, Fiction. by Richard Gabriel (2001) Amazon.com;

Pharaonic Rule in Ancient Egypt

The pharaohs were powerful but distant figures. They were the heads of state and the highest priests and were worshiped as gods. Their power was absolute and they were required to perform certain duties and govern judicially with “ ma’at” (harmony, balance, peace and order). Running the military and deciding policy was only a small part of their job. Succession was from father to son, preferably the son of the king and queen, but if there were no such offspring then the son of one of the Pharaoh’s “secondary” or “harem” wives.

Dorothy Arnold, an Egyptologist at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, told the New Yorker: "The pharaoh was believed in. As whether he was beloved that is beside the point: he was necessary. He was life itself. He represented everything good. Without him there would be nothing." The power of the Pharaohs was based in part on their ability to predict the annual flooding of the Nile.

In ancient Egypt, the idea prevailed that the whole machinery of the state was set in motion by the will of the ruler alone; the taxes were paid to fill his treasury, wars were undertaken for his renown, and great buildings were erected for his honor. All the property of the country was his by right, and if he allowed any of his people to share it, it is only as a loan, which he could reclaim at any moment. His subjects also belonged to him, and he could dispose of their lives at his will.[Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894 **]

This was the theoretical view, which was impossible to carry out in practice, for the king, though supposed to dispose of everything as a god, was rarely able to act independently. It is true that the great body of the nation was unrecognized in old times; yet other factors existed which could render a ruler powerless, however absolute he might appear to be.

Around the king were the old counselors who had served his father, and whom the clerks and officials were accustomed blindly to obey, as well as the generals with the troops in their pay, and the priesthood with their unlimited power over the lower classes. In the small towns the old rich families of the nobility, residing in their country seats, were nearer to the homes of the people than the monarch dwelling in his distant capital. The king was afraid to offend any of these powerful people; he had to spare the sensitive feelings of the minister; discover a way of gratifying the ambition of the general without endangering the country; watch carefully that his officers did not encroach on the rights of the nobility; and above all keep in favor with the priests. It was only when the king could satisfy all these claims, and understand at the same time how to play off one part} against another, that he could expect a long and prosperous reign.

Threats to a Pharaoh’s Power

If the Pharaoh failed in any way, his chances were small, for there lurked close to him his most dangerous enemies, his nearest relatives. There always existed a brother or an uncle, who imagined he had a better claim to the throne than the reigning king, or there were the wives of the late ruler, who thought it a fatal wrong that the child of their rival rather than their own son should have inherited the crown. During the lifetime of the king they pretended to submit, but they waited anxiously for the moment to throw off the mask. They understood well how to intrigue, and to aggravate any misunderstanding between the king and his counselors or his generals, until at last one of them, who thought himself slighted or injured, proceeded to open rebellion, and began the war by proclaiming one of the pretenders as the only true king, who had wrongfully been kept from the throne.

In the meantime, in those parts of the country where there was no civil war, events followed their peaceful course. The people however felt it bitterly when the government was weak. The taxes were raised, and were gathered in irregularly to satisfy the greed of the soldiers, the officials became more shameless in their extortions and caprices, and the public buildings, the canals and the dykes, fell into decay. Under these circumstances the nobility' and priesthood alone flourished; when no central power existed they became more and more independent, and were able to obtain fresh concessions and gifts from each new claimant. A new ruler ruler had to expend much energy to keep things a manageable state.

Even powerful rulers lived in constant danger from their own relatives, as is shown by the conspiracy against Ramses III. The reign of this king was certainly a most brilliant one, the country was at last at peace, and the priesthood had been won by the building of great temples and by immense presents. All appeared propitious, yet even in this reign those fatal under-currents were at work which caused the speedy downfall of each dynasty, and it was perhaps due only to a happy chance that this king escaped. A conspiracy broke out in his own harem headed by a distinguished lady of the name of Tey, who was certainly of royal blood, and indeed may have been either his mother or stepmother.

See Separate Article: See Harem Conspiracy Under RAMSES III (1195 – 1164 B.C.): THE LAST GREAT PHARAOH africame.factsanddetails.com

Succession of the Kings of Ancient Egypt

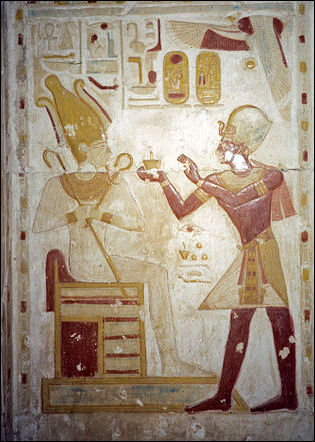

Ramses III and Prince Amenherkhepeshef before Hathor

Succession was from father to son, preferably the son of the king and queen, but if there were no such offspring then the son of one of the Pharaoh’s “secondary” or “harem” wives. Susan Allen of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The descent of kingship was usually from father to son, but the role of mothers and queens was equally important. Ideally, the successor was the son of the king by the chief royal wife, who, as a close blood relative of the king, provided a double legitimacy to the succession. Throughout Egyptian history, the role of the queen as mother of the king, and therefore as a symbol of the powers of creation and rebirth, gave royal women considerable status and influence. Occasionally for political or dynastic reasons, queens assumed the kingship but, except for Hatshepsut, their reigns were usually brief. [Source: Susan Allen, Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

“While historical records of succession are few, it seems that the inherent desire for the proper order of the world mitigated against usurpation of power and messy dynastic affairs such as were seen in the Ptolemaic Period (304–30 B.C.). The most important task of a king on his succession was to see to the burial of his predecessor and therefore to ensure order in both this world and the afterlife. The office of kingship was also flexible enough to allow for an occasional coregency, in which two rulers, an elder king and his junior partner, governed jointly.” \^/

Coronation of a Pharaoh

We know little of the details of the ceremonies of the day of accession; it was kept as a yearly festival, and celebrated with special splendor on the 30th anniversary. One representation only is known of a festival which apparently belongs to the coronation festivities, such as the great processional and sacrificial festival, which the king solemnizes to his father Min, the god who causes the soil to be fertile. It was natural that the king should begin his reign over this agricultural country with a sacrifice to the god of the fields. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

We first see how the king, “shining as the sun," leaves the “palace of life, steadfastness, and purity, and is borne towards the house of his father Min, to behold his beauty. " The Pharaoh is seated under a canopy in a richly decorated sedan-chair, he is carried by some of his sons, while others fan him with their large fans. Two priests walk in front burning incense; a third, the reciter-priest, reads “all that is customary before the king as he goes forth. " A company of royal relatives, royal children and great princes, precede the king, others follow; at the head of the procession are drummers and trumpeters, while in the rear march the soldiers.

In the meantime the god Min has left his sanctuary and advances to meet the king. Twenty priests bear the covered stand, on which is the image of the god; others fan the god with bouquets and fans. The “white bull," sacred to the god, walks pensively before him, and a long procession of priests follow, carrying the insignia of kingship, and divine symbols; also images of the royal ancestors, the statues of the kings of Upper and Lower Egypt. In the meantime the reciter-priest reads from the strange book the “words of the Africans," and the procession advancing meets that of the king, which is waiting on a terrace, where two flag-staves bearing the head-dress of the god have been erected. Here the priest lets fly four geese, to carry the news to the gods of the four quarters ot heaven, that “Horus the son of Isis and Osiris has received the white and the red crown, that King Ramses has received the white and the red crown. "

When the monarch has thus been proclaimed king to the gods, he offers his royal sacrifice in the presence of the statues of his ancestors. A priest presents him with the golden sickle, with which he cuts a sheaf of corn, he then strews it before the white bull, symbolising the offering of the first fruits of his reign. He then offers incense before the statue of the god, while the priest recites from the mysterious books of the “dances of Min. " When the Pharaoh, with these and similar ceremonies, has taken upon him the dignity of his father he next receives the congratulations of his court. If any of the high officials are unavoidably absent, they send congratulatory letters: such as the treasurer Oagabu sends the following poem to Seti II. on his coronation,- that it may be read in the palace of Merymat in the horizon of Ra: “Incline thine ear towards me, thou rising Sun, Thou who dost enlighten the two hinds with beauty; The sunshine of mankind, chasing darkness from Egypt! Thy form is as that of thy father Ra rising in the heavens,

According to a legend Orisis employed the same messengers to announce his accession to the other gods: “Thy rays penetrate to the farthest lands. When thou art resting in thy palace, Thou hearest the words of all countries; For indeed thou hast millions of ears; Thine eye is clearer than the stars of heaven; Thou seest farther than the Sun. If I speak afar off, thine ear hears; If I do a hidden deed, thine eye sees it. O Ra, richest of beings, chosen of Ra, Thou king of beauty, giving breath to all. "

Rituals and Duties of the Kings of Ancient Egypt

Orisis It is believed that Pharaohs performed many duties and presided over many rituals. Mundane ceremonies are believed to have been performed by his sons. By buildings temples and making offerings the Pharaoh was of continuously renewing the bond the between the people, the Pharaoh and the gods.

Susan Allen of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The ancient Egyptians regarded their king and the office of kingship as the apex and organizing principle of their society. The king's preeminent task was to preserve the right order of society, also called maat. This included ensuring peace and political stability, performing all necessary religious rituals, seeing to the economic needs of his people, providing justice, and protecting the country from external and internal danger. It has sometimes been said that the ancient Egyptians believed their kings to be divine, but it was the power of kingship, which the king embodied, rather than the individual himself that was divine. The living king was associated with the god Horus and the dead king with the god Osiris, but the ancient Egyptians were well aware that the king was mortal. One of their most ancient rituals was the sed festival, or jubilee, at which the mortal king reaffirmed his fitness to continue as king. [Source: Susan Allen, Department of Egyptian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004, metmuseum.org \^/]

After a pharaoh had been on the throne for 30 years a jubilee was held. From then on another was held every three years. During the celebration, which dates back to original pharaohs, rituals and feasts were held. The king's coronation was re-enacted. To top it all off the pharaoh was supposed to run around a track to demonstrate his fitness. Ramses had 13 jubilees. It is hard to imagine him going for a jog on his last one when he was he was nearly 90.♣

See Separate Article: GODS AND RITUALS AND DUTIES OF THE EGYPTIAN PHARAOHS africame.factsanddetails.com

Pharaohs, the Gods and the Afterlife

The pharaohs were considered to be gods — incarnations of falcon-head Horus, children of the sun god Re. They were descendants of the Amun, regarded as the first Egyptian king, who in turn descended from the sun-god Ra and the falcon god of kingship Horus. Egyptians believed they were given their authority to rule when the world was created.

Referred to as the "lord of all the sun disk encircles," the Pharaoh was believed to be one with the universe and the gods and was regarded as an intermediary between the gods and people on earth. Through them the life force was conveyed from the gods to the people. A Pharaoh’s coronation was viewed not as "the making of a god but the revealing of a god." According to the ancient Egyptians, the pharaohs were the link between heaven and the earth and their breath kept the two worlds separate.♣

Silke Roth of Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, Germany wrote: “Essentially, ancient Egyptian kingship was represented by the king in correlation with the queen. However, as an earthly embodiment of the principle deity (the sun god), the king played a predominant role. Usually he was portrayed unaccompanied. In the infrequent portrayals where he was attended by royal women, the king usually played the leading part by preceding the queen and performing the central action; moreover, he was often depicted on a larger scale.” [Source: Silke Roth, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology 2009, escholarship.org ]

See Separate Article: GODS AND RITUALS AND DUTIES OF THE EGYPTIAN PHARAOHS africame.factsanddetails.com

Palace of the Pharaoh

The “great house" in which the Pharaoh resided was not only the dwelling-place of a god (his horizon as the Egyptians were accustomed to call it), but also the seat of government, the heart of the country. This double definition was carried out in the disposition of the royal house, which was always divided into two parts, an outer part serving for audiences; an inner one, the dwelling of the ' good god. " The outer division is the large battlemented enclosure; the inner part is the narrow richly decorated building. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

These two parts of the palace were sharply defined, especially during the Old Kingdom, when the titles of the court officials showed to which division their owners belonged. Audiences were held in the part serving for audeince."' The inner palace on the other hand was the home of the king, and whoever was called governor of the palace was either a prince or a personal servant of the king, a lord-chamberlain.

In the palace itself, during the Old Kingdom, there were various divisions: there was the great hall of pillars, which was used for council meetings, and, still more important, there was the House of Adoration and the King's Room. Only the king's sons, his nearest friends, and the governor of the palace were allowed to bear the title of “Privy Councillor of the House of Adoration". The Egyptian king had several palaces in the different towns of his kingdom, and Ramses II and Ramses III made for themselves noble palaces even in the two temples, which they built to Amun on the west side at Thebes.

Palaces and Royal Residence in Amarna

Amarna north palace

Anna Stevens of Cambridge University wrote: “The full extent of the North Riverside Palace “has never been mapped and all that is visible today is a part of the thick, buttressed eastern enclosure wall, although excavations in 1931-1932 exposed a small stretch of what may have been the palace wall proper. To the north of the palace, and perhaps once part of it, is a large terraced complex containing open courts and magazines known as the North Administrative Building. The land to the east of the palace is occupied by houses that include several very large, regularly laid out estates, and also areas of smaller housing units beyond, running up to the base of the cliffs. [Source: Anna Stevens, Amarna Project, 2016, UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 2013 escholarship.org ]

“This is the best recorded of the Amarna palaces, having been excavated first in the early 1920s and recleared and restudied in the 1990s. The palace was built around two open courts separated by a pylon or possible Window of Appearance, the second court containing a large basin that probably housed a sunken garden. Opening off each courtyard was a series of smaller secondary courts containing altars, magazines, an animal courtyard, probable service areas, and a throne room. A feature of the site was the good preservation of its wall paintings when exposed in the 1920s

“The North Palace and North Riverside Palace are generally thought to have been the main residences for the royal family, the palaces in the Central City playing more ceremonial and administrative roles. The North Palace has often been assigne d to female members of the royal family, whose names appear prominently here, although Spence considers it more likely that royal women had chambers within the North and North Riverside Palaces rather than an entirely separate residence.

“To the south again is a walled complex now termed the King’s House that was connected to the Great Palace by a 9 meters wide mud-brick bridge running over the Royal Road. At the King’s House, the bridge descended into a tree-filled court that led to a columned hall with peripheral apartments, one of which contained a probable throne platform. The famous painted scene of the royal family relaxing on patterned cushions originates from this building; other painted scenes include that of foreign captives, perhaps connected with a Window of Appearance. The complex also contained, in its final form, a large set of storerooms.

“Extending beyond the King’s House to the east was a series of administrative buildings, roughly arranged into a block, among them the “Bureau of Correspondence of Pharaoh,” where most of the Amarna Letters were probably found, an d the “House of Life.” To their south is a set of uniformly laid out houses generally thought to have been occupied by administrators employed in the Central City. In the desert to the east lies a complex identified by the EES excavato rs as military/police quarters. Nearby were several further enclosures, among them a small shrine, the House of the King’s Statue, which has been suggested as a state-built public chapel, perhaps built for those who worked in the Central City.”

Symbols and Crowns of the Egyptian Pharaoh

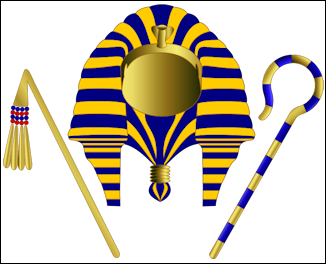

As a sign of their authority a pharaoh wore a false beard, a lion’s main and a “nemes” or headcloth with a sacred cobra. When offering were made he waived the royal “sekhem” (scepter) over them. The beard on the statue of a pharaoh identifies him as being one with Osiris, god of the dead. The cobra and vulture on his forehead symbolize the Upper and Lower kingdoms of Egypt. When the king sat on his throne wearing all of his symbols of office—the crowns, scepters, and other ceremonial items—it was believed the spirit of the great god Horus spoke through him.

crook and flail, Pharaoh symbols The crook and flail held the Pharaoh’s hands symbolized the king's power and authority and also linked him with Osiris (statues of Osiris also have a crook and flail). The crook was a short stick curved at the top, much like a shepherd’s crook. The flail was a long handle with three strings of beads. The pharaoh's power was also symbolized by a flabellum (fan) held in one hand.

The sickleshaped sword {Khopesh), named after its shape, also seems to have been a symbol of royalty. The regalia of the Pharaohs seems to belong to a time which the Egyptian wore nothing but a loincloth, and when it was considered a special distinction that the king should complete this loincloth with a piece of skin or matting in front, and should adorn it behind with a lion's tail.

Crowns and headdresses were mostly made of organic materials and have not survived but we know what they looked like from many pictures and statues. The best known crown is from Tutankhamun’s golden death mask. The White Crown represented Upper Egypt, and the Red Crown, Lower Egypt (around the Nile Delta). Sometimes these crowns were worn together and called the Double Crown, and were the symbol of a united Egypt.

See Separate Article: SYMBOLS OF THE PHARAOHS africame.factsanddetails.com

Royal Names in Ancient Egypt

The royal names and titles always appeared to the Egyptians as a matter of the highest importance. The first title consisted of the name borne by the king as a prince. This was the only one used by the people or in history; it was too sacred to be written as an ordinary word, and was therefore enclosed in an oval ring in order to separate it from other secular words. Before it stood the title “King of Upper Egypt and King of Lower Egypt. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The unification of Upper Egypt (southern Egypt) and the Lower Egypt (northern Egypt) was of great importance in the history of Egypt. The official title of the Pharaoh was always the “King of Upper Egypt and the King of Lower Egypt. " It was the same with the titles of his servants; originally they were the superintendents of the two houses of silver, or of the two storehouses, for each kingdom had its own granary and its own treasury.

During the Old Kingdom the idea arose that it was not suitable that the king, who on ascending the throne became a demigod, should retain the same common name he had borne as a prince. As many ordinary people were called Pepi, it did not befit the good god to bear this vulgar name; therefore at his accession a new name was given him for official use, which naturally had some pious signification. Pepi became "the beloved of Ra"; 'Esse, when king, was called, "the image of Ra stands firm"; and Mentuhotep is called “Ra, the lord of the two countries. " We see that all these official names contain the name of Ra the Sun-god, the symbol of royalty. Nevertheless, the king did not give up the family name he had borne as prince, for though not used for official purposes, it yet played an important part in the king's titles.

See Separate Article: ROYAL NAMES IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Courtiers of the Pharaoh

Over and over again we meet phrases praising the Pharaoh such as "He knew the place of the royal foot, and followed his benefactor in the way, he followed Horus in his house, he lived under the feet of his master," he was beloved by the king more than all the people of Egypt, he was loved by him as one of his friends, he was his faithful servant, dear to his heart, he was in truth beloved by his lord.'" in the tombs of the great men, and all that they signify is that the deceased belonged to the court circle, or in the Egyptian language the “Chosen of the Guard. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

" These courtiers watched jealously lest one should approach the monarch nearer than another; there were certain laws, the “customs of the palace and the maxims of the court," which were strictly observed by the officials who "allowed the courtiers to ascend to the king. " This presentation of the courtiers in order of precedence was openly considered as a most important business, and those whose duty it was to “range the princes in their places,' to appoint to the friends of the king their approach when standing or sitting," boast how excellently they performed their duty.

We know little more of the ceremonial of the Egyptian court; the fact that King Shepseskaf allowed Ptahshepses, one of his grandees,to kiss his foot instead of kissing the ground before him, shows us how strict etiquette was even during the Old Kingdom. It is noteworthy that the man chosen out for this high honour was not only the high priest of Memphis, but also the son-in-law of His Majesty. During the Old Kingdom these conventionalities were carried farther than in any later time; and the long list of the titles of those officials shows us that the court under the pyramid-builders had many features in common with that of the Byzantines.

Meeting the Pharaoh

During the Old Kingdom is seems it was customary for people meeting the Pharaoh to kiss his foot or kiss the ground before him. During the New Kingdom this customs appears to have been rather out of fashion, at any rate for the highest officials; the words may occur occasionally in the inscriptions, but in the pictures the princes only bow, either with their arms by their sides or with them raised in prayer before His Majesty. The priests also, when receiving the king ceremoniously at the gates of the temples, only bow respectfully, and even their wives and children do the same as they present the Pharaoh with flowers and food in token of welcome; it is only the servants who throw themselves down before him and kiss the earth at the sight of the monarch.

It seems to have been the custom during the New Kingdom to greet the king with a short psalm when they “spoke in his presence “(it was not etiquette to speak “to him ") — such as when the king had called his councillors together, and had set forth to them how he had resolved to bore a well on one of the desert roads, and had asked them for their opinion on the subject, we might expect them straightway to give him an answer, especially as already on their entrance into the hall they had “raised their arms praising him. "

Rhampsinit and the Masterthief (Dutch TV, 1973)

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Amarna Palace, the Amarna Project

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024