Home | Category: Government, Military and Justice

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN GOVERNMENT

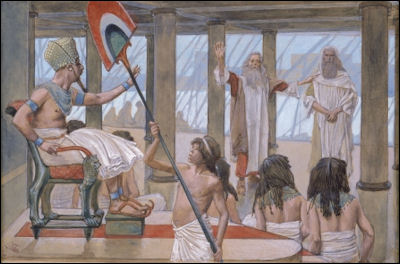

Tissot's painting of Moses speaking to the Pharaoh Egypt was unified as a kingdom about 3300 B.C. A national bureaucracy supervised the construction of canals and monuments and pyramids (2700 BC). The brilliant first dynasty made great achievements in architecture, sculpture and painting, tradition followed by subsequent dynasties. [Source: World Almanac]

Except for occasional periods of turmoil as dynasties changed, ancient Egypt was ruled by absolute, deified monarchs for nearly three thousand years. Roughly equivalent in size and location to modern Egypt, the ancient kingdom featured a centralized administration, an influential priesthood, and powerful officials called “viziers”, who helped the king govern. The viziers acted as mayors, tax collectors, and judges. Other high officials who served the king included a treasurer and an army commander. [Source: Gale Encyclopedia of World History: Governments, Thomson Gale, 2008]

With the emergence of a strong, centralized government under a god-king, the country's nascent economic and political institutions became subject to royal authority. The central government, either directly or through major officials, became the employer of soldiers, retainers, bureaucrats, and artisans whose goods and services benefited the upper classes and the state gods. In the course of the Early Dynastic Period, artisans and civil servants working for the central government fashioned the highly sophisticated traditions of art and learning that thereafter constituted the basic pattern of pharaonic civilization. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Egypt: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1990]

One reason Egypt was able to build such large temples and pyramids is that was relatively untroubled by wars and could devotes its manpower to construction projects rather than an army. In the ancient world it was common for leaders to marry women from rival kingdoms to form alliances and maintain peace but this tactic was not widely used in ancient Egypt, whose rulers tended to regard foreigners with disdain.

In his book “The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” Toby Wilkinson argued that the ancient Egyptians “invented the concept of the nation-state that still dominates our planet,” Mr. Wilkinson writes that the country’s earliest kings not only “formulated and harnessed” traditional tools of leadership’slike using ideology and ceremony to unite a disparate population and bind it to the state’sbut also used more malign instruments like police surveillance, xenophobia and the brutal repression of dissent to cement their power. [Source: Michiko Kakutani, New York Times March 28, 2011]

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“State in Ancient Egypt, The: Power, Challenges and Dynamics” by Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia (2019) Amazon.com;

“Early Dynastic Egypt” by Toby A.H. Wilkinson (2001) Amazon.com;

“The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt” by Toby Wilkinson (2010) Amazon.com;

”Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians: Volume 1: Including their Private Life, Government, Laws, Art, Manufactures, Religion, and Early History (Cambridge Library Collection - Egyptology) by John Gardner Wilkinson (1797–1875) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt” by Ian Shaw , Illustrated (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt” by Salima Ikram (2013) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization” by Barry Kemp (1989, 2018) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Egyptian State: The Origins of Egyptian Culture (c. 8000–2000 BC)” by Robert J. Wenke (2009) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egypt and Early China: State, Society, and Culture” by Anthony J. Barbieri-Low and Marissa A. Stevens (2021) Amazon.com

“Ancient Egyptian Administration (Handbook of Oriental Studies: Section 1; The Near and Middle East) by Juan Carlos Moreno García (2013) Amazon.com;

"The Administration of Egypt in the Old Kingdom: The Highest Titles and Their Holders" by Naguib Kanawati and Nigel Strudwick Amazon.com;

“Local Elites and Central Power in Egypt during the New Kingdom”

by Marcella Trapani Amazon.com;

Structure of the Ancient Egyptian Government

ncient Egypt was a conservative society with a deep reverence for the past. Once established, its institutions were difficult to change. Perhaps the most resistant of all was the monarchy. A pharaoh (king) of the twenty-first dynasty ruled much as his predecessors had a thousand years earlier. [Source: Gale Encyclopedia of World History: Governments, Thomson Gale, 2008]

Between the masses and their king stood a huge group of slaves, craftsmen, soldiers, scribes, priests, and specialists. You can see how big this group was from the hundreds of small tombs that surround each of the royal pyramids at Giza. When servants of the pharaoh died, they were buried close to his tomb so they could serve him in the afterlife.

One of the most important people in the Pharaoh's administration was the court magician, partly because he was thought to have a great understanding of astronomy, anatomy, and the physical world. However, even the court magician's power was overshadowed by that of the pharaoh's two viziers, one for Upper Egypt and one for Lower Egypt. Sometimes the same person held both posts. Viziers were in charge of paying people, taking notes, and giving advice. Some of them might have also been in charge of the treasury. This meant that they were responsible for most of the government's daily operations. If a vizier was corrupt, it could cause a lot of problems.

The priests were by far the most powerful of the palace factions, particularly the priests of Amun, who was the sun god, the patron of the royal capital of Thebes, and the traditional favorite of the pharaohs. The priests were a powerful force, as we can see from the rise and fall of the pharaoh Akhenaton (fourteenth century B.C.). It's likely that personal inclination and circumstance played a part, but it's also probable that it was a combination of the two. Akhenaton developed an antipathy toward Amun soon after taking the throne.

Pharaonic Rule in Ancient Egypt

Thutmose III

A pharaoh was seen as divine, so they were above the everyday business of government and daily life. He didn't interact with the general public much, and even the highest-ranking visitors had to bow down on the ground when they entered his presence. Only a few of the pharaoh's servants ever actually met him in person. [Source: Gale Encyclopedia of World History: Governments, Thomson Gale, 2008]

Pharaohs ruled by issuing edicts, often through the viziers. If the edict had implications outside the palace walls, it was passed on to the governors of the provinces, who were called nomarchs. As the nomarchs were the pharaoh's main representatives in the countryside, they were responsible for a lot of the administrative work, especially when it came to collecting taxes. The stewards of the many royal estates and temple properties scattered throughout the country were also pretty important.

The throne was usually passed from father to son, with the latter often serving as a co-regent first. Co-regency gave the young successor a chance to gain experience in more responsible roles, and it also showed the public that the new leader had the king's support. If someone wanted to take over the throne, they'd have a hard time convincing anyone if the previous king had chosen his successor. When a pharaoh died suddenly or without heirs, though, a period of violent turmoil often followed as rivals vied for the throne.

See Separate Article: PHARAOHS: KINGS AND QUEENS OF ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Instruction of Ptah-Hotep (2200 B.C.) on Leadership and Rulers

The Instruction of Ptahhotep is an ancient Egyptian literary composition written by the Vizier Ptahhotep, during the rule of King Izezi of the Fifth Dynasty. Regarded as one of the best examples of wisdom literature, specifically under the genre of Instructions that teach something, of Ptahhotep addresses various virtues that are necessary to live a good life in accordance with Maat (justice) and offers insight into Old Kingdom — and ancient Egyptian — thought, morality and attitudes. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Instruction of Ptahhotep ( c. 2200 B.C.) reads: “If you have, as leader, to decide on the conduct of a great number of men, seek the most perfect manner of doing so that your own conduct may be without reproach. Justice is great, invariable, and assured; it has not been disturbed since the age of Ptah. To throw obstacles in the way of the laws is to open the way before violence. Shall that which is below gain the upper hand, if the unjust does not attain to the place of justice? Even he who says: I take for myself, of my own free-will; but says not: I take by virtue of my authority. The limitations of justice are invariable; such is the instruction which every man receives from his father. [Source: Charles F. Horne, “The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East” (New York: Parke, Austin, & Lipscomb, 1917), Vol. II: Egypt, pp. 62-78, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt, Fordham University]

“Inspire not men with fear, else Ptah will fight against you in the same manner. If any one asserts that he lives by such means, Ptah will take away the bread from his mouth; if any one asserts that he enriches himself thereby, Ptah says: I may take those riches to myself. If any one asserts that he beats others, Ptah will end by reducing him to impotence. Let no one inspire men with fear; this is the will of Ptah. Let one provide sustenance for them in the lap of peace; it will then be that they will freely give what has been torn from them by terror.

“If you are among the persons seated at meat in the house of a greater man than yourself, take that which he gives you, bowing to the ground. Regard that which is placed before you, but point not at it; regard it not frequently; he is a blameworthy person who departs from this rule. Speak not to the great man more than he requires, for one knows not what may be displeasing to him. Speak when he invites you and your worth will be pleasing. As for the great man who has plenty of means of existence, his conduct is as he himself wishes. He does that which pleases him; if he desires to repose, he realizes his intention. The great man stretching forth his hand does that to which other men do not attain. But as the means of existence are under the will of Ptah, one can not rebel against it.

Ramses III sarcophagus detail

“If you are one of those who bring the messages of one great man to another, conform yourself exactly to that wherewith he has charged you; perform for him the commission as he has enjoined you. Beware of altering in speaking the offensive words which one great person addresses to another; he who perverts the trustfulness of his way, in order to repeat only what produces pleasure in the words of every man, great or small, is a detestable person.

“If you are employed in the larit, stand or sit rather than walk about. Lay down rules for yourself from the first: not to absent yourself even when weariness overtakes you. Keep an eye on him who enters announcing that what he asks is secret; what is entrusted to you is above appreciation, and all contrary argument is a matter to be rejected. He is a god who penetrates into a place where no relaxation of the rules is made for the privileged.

“If you are with people who display for you an extreme affection, saying: "Aspiration of my heart, aspiration of my heart, where there is no remedy! That which is said in your heart, let it be realized by springing up spontaneously. Sovereign master, I give myself to your opinion. Your name is approved without speaking. Your body is full of vigor, your face is above your neighbors." If then you are accustomed to this excess of flattery, and there be an obstacle to you in your desires, then your impulse is to obey your passion. But he who . . . according to his caprice, his soul is . . ., his body is . . . While the man who is master of his soul is superior to those whom Ptah has loaded with his gifts; the man who obeys his passion is under the power of his wife.

“Declare your line of conduct without reticence; give your opinion in the council of your lord; while there are people who turn back upon their own words when they speak, so as not to offend him who has put forward a statement, and answer not in this fashion: "He is the great man who will recognize the error of another; and when he shall raise his voice to oppose the other about it he will keep silence after what I have said."

“If you are a leader, setting forward your plans according to that which you decide, perform perfect actions which posterity may remember, without letting the words prevail with you which multiply flattery, which excite pride and produce vanity.

“If you are a leader of peace, listen to the discourse of the petitioner. Be not abrupt with him; that would trouble him. Say not to him: "You have already recounted this." Indulgence will encourage him to accomplish the object of his coming. As for being abrupt with the complainant because he described what passed when the injury was done, instead of complaining of the injury itself let it not be! The way to obtain a clear explanation is to listen with kindness.

Instruction of Ptah-Hotep (2200 B.C.) on How to Treat a Great Man

The Instruction of Ptahhotep ( c. 2200 B.C.) reads: “Disturb not a great man; weaken not the attention of him who is occupied. His care is to embrace his task, and he strips his person through the love which he puts into it. That transports men to Ptah, even the love for the work which they accomplish. Compose then your face even in trouble, that peace may be with you, when agitation is with . . .These are the people who succeed in what they desire. [Source: Charles F. Horne, “The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East” (New York: Parke, Austin, & Lipscomb, 1917), Vol. II: Egypt, pp. 62-78, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt, Fordham University]

“Teach others to render homage to a great man. If you gather the crop for him among men, cause it to return fully to its owner, at whose hands is your subsistence. But the gift of affection is worth more than the provisions with which your back is covered. For that which the great man receives from you will enable your house to live, without speaking of the maintenance you enjoy, which you desire to preserve; it is thereby that he extends a beneficent hand, and that in your home good things are added to good things. Let your love pass into the heart of those who love you; cause those about you to be loving and obedient.

“If you have become great after having been little, if you have become rich after having been poor, when you are at the head of the city, know how not to take advantage of the fact that you have reached the first rank, harden not your heart because of your elevation; you are become only the administrator, the prefect, of the provisions which belong to Ptah. Put not behind you the neighbor who is like you; be unto him as a companion.

“Bend your back before your superior. You are attached to the palace of the king; your house is established in its fortune, and your profits are as is fitting. Yet a man is annoyed at having an authority above himself, and passes the period of life in being vexed thereat. Although that hurts not your . . . Do not plunder the house of your neighbors, seize not by force the goods which are beside you. Exclaim not then against that which you hear, and do not feel humiliated. It is necessary to reflect when one is hindered by it that the pressure of authority is felt also by one's neighbor.

“Do not make . . . you know that there are obstacles to the water which comes to its hinder part, and that there is no trickling of that which is in its bosom. Let it not . . . after having corrupted his heart.

“If you aim at polished manners, call not him whom you accost. Converse with him especially in such a way as not to annoy him. Enter on a discussion with him only after having left him time to saturate his mind with the subject of the conversation. If he lets his ignorance display itself, and if he gives you all opportunity to disgrace him, treat him with courtesy rather; proceed not to drive him into a corner; do not . . . the word to him; answer not in a crushing manner; crush him not; worry him not; in order that in his turn he may not return to the subject, but depart to the profit of your conversation.

“Let your countenance be cheerful during the time of your existence. When we see one departing from the storehouse who has entered in order to bring his share of provision, with his face contracted, it shows that his stomach is empty and that authority is offensive to him. Let not that happen to you; it is . . .

“Know those who are faithful to you when you are in low estate. Your merit then is worth more than those who did you honor. His . . ., behold that which a man possesses completely. That is of more importance than his high rank; for this is a matter which passes from one to another. The merit of one's son is advantageous to the father, and that which he really is, is worth more than the remembrance of his father's rank.

“Distinguish the superintendent who directs from the workman, for manual labor is little elevated; the inaction of the hands is honorable. If a man is not in the evil way, that which places him there is the want of subordination to authority.

Instruction of Ptah-Hotep (2200 B.C.) on Being a Loyal Subject

The Instruction of Ptahhotep ( c. 2200 B.C.) reads: “If you are a farmer, gather the crops in the field which the great Ptah has given you, do not boast in the house of your neighbors; it is better to make oneself dreaded by one's deeds. As for him who, master of his own way of acting, being all-powerful, seizes the goods of others like a crocodile in the midst even of watchment, his children are an object of malediction, of scorn, and of hatred on account of it, while his father is grievously distressed, and as for the mother who has borne him, happy is another rather than herself. But a man becomes a god when he is chief of a tribe which has confidence in following him. [Source: Charles F. Horne, “The Sacred Books and Early Literature of the East” (New York: Parke, Austin, & Lipscomb, 1917), Vol. II: Egypt, pp. 62-78, Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt, Fordham University]

“If you abase yourself in obeying a superior, your conduct is entirely good before Ptah. Knowing who you ought to obey and who you ought to command, do not lift up your heart against him. As you know that in him is authority, be respectful toward him as belonging to him. Wealth comes only at Ptah's own good-will, and his caprice only is the law; as for him who . . Ptah, who has created his superiority, turns himself from him and he is overthrown.

“Be active during the time of your existence, do no more than is commanded. Do not spoil the time of your activity; he is a blameworthy person who makes a bad use of his moments. Do not lose the daily opportunity of increasing that which your house possesses. Activity produces riches, and riches do not endure when it slackens.

“If you are a wise man, bring up a son who shall be pleasing to Ptah. If he conforms his conduct to your way and occupies himself with your affairs as is right, do to him all the good you can; he is your son, a person attached to you whom your own self has begotten. Separate not your heart from him.... But if he conducts himself ill and transgresses your wish, if he rejects all counsel, if his mouth goes according to the evil word, strike him on the mouth in return. Give orders without hesitation to those who do wrong, to him whose temper is turbulent; and he will not deviate from the straight path, and there will be no obstacle to interrupt the way.

“If you desire to excite respect within the house you enter, for example the house of a superior, a friend, or any person of consideration, in short everywhere where you enter, keep yourself from making advances to a woman, for there is nothing good in so doing. There is no prudence in taking part in it, and thousands of men destroy themselves in order to enjoy a moment, brief as a dream, while they gain death, so as to know it. It is a villainous intention, that of a man who thus excites himself; if he goes on to carry it out, his mind abandons him. For as for him who is without repugnance for such an act, there is no good sense at all in him.

Admonitions of Ipuwer: Earliest Treatise on Political Ethics

The Ipuwer Papyrus (officially Papyrus Leiden I 344 recto) is an ancient Egyptian hieratic papyrus made during the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt, and now held in the Dutch National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, Netherlands. It contains the Admonitions of Ipuwer, an incomplete literary work whose original composition is dated no earlier than the late Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt (c.1991-1803 B.C.). The Ipuwer Papyrus has been dated no earlier than the Nineteenth Dynasty, around 1250 B.C. but it is now agreed that the text itself is much older, and dated back to the Middle Kingdom, more precisely the late Twelfth Dynasty. [Source: Wikipedia +]

It was previously thought that the Admonitions of Ipuwer presents an objective portrait of Egypt in the First Intermediate Period. In more recent times, it was found that the Admonitions, along with the Complaints of Khakheperresenb, are most likely works of royal propaganda, both inspired by the earlier Prophecy of Neferti: the three compositions have in common the theme of a nation that has been plunged into chaos and disarray and the need for an intransigent king who would defeat chaos and restore maat. Toby Wilkinson suggested that the Admonitions and Khakheperresenb may thus have been composed during the reign of Senusret III, a pharaoh well known for his use of propaganda. In any case, the Admonitions is not a reliable account of early Egyptian history, because of the long time interval between its original composition and the writing of the Leiden Papyrus.

The Admonitions is considered the world's earliest known treatise on political ethics, suggesting that a good king is one who controls unjust officials, thus carrying out the will of the gods. It is a textual lamentation, close to Sumerian city laments and to Egyptian laments for the dead, using the past (the destruction of Memphis at the end of the Old Kingdom) as a gloomy backdrop to an ideal future.

Local Government and Bureaucracy in Ancient Egypt

Local government were run by mayors, councils of elders, priests and ministers under the pharaoh. Judging from the objects found in a mayor's home they lived fairly lavishly and had high status.

Based on the displays of wealth at 3700-year-old site in Abydos, where a large palace was found, and a 2600-year-old site at the Bahariya Oasis, where a rich tomb was found, archaeologists have deduced that sometimes governors and mayors amassed great political power and in some cases may have challenged the ruling pharaohs.

See Separate Article: LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Egyptians had an efficient bureaucracy which collected taxes to finance grand projects. Even low bureaucrats sometimes viewed themselves as big shots.

The Egyptians were very bureaucratic. They liked to make records and lists. Only a handful of which have made it to modern times because they were written on papyrus. It has been suggested that the Egyptians affinity with bureaucracy was linked to reverence of the past and need to preserve it.

See Separate Article: BUREAUCRACY IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Taxes in Ancient Egypt

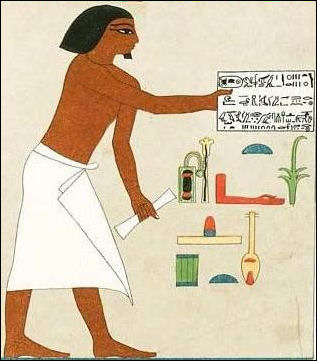

The Egyptians paid for their grand projects with stiff taxes. They kept meticulous records of who owed what and cracked down ruthlessly on those who didn't pay their share. Tomb paintings show clerks tallying up crops produced at harvest and making lists with a reed pen. They also show clerks monitoring beer breweries, slaughterhouses and workshops.

Tax collectors punished deadbeats by beating and flogging and torturing to death. Peasants were sometimes bound by their hands and feet and thrown into the irrigation ditches to drown. A tomb painting, dated around 2400 B.C., shows a tax official meeting with a group who hadn't paid their taxes. The next scene shows some of them being flogged.

When it came to collecting taxes, in the form of a proportion of farm produce, we must assume a network of officials operated on behalf of the state throughout Egypt. There can be no doubt that their efforts were backed up by coercive measures. The inscriptions left by some of these government officials, mostly in the form of seal impressions, allow us to re-create the workings of the treasury, which was by far the most important department from the very beginning of Egyptian history. Agricultural produce collected as government revenue was treated in one of two ways. A certain proportion went directly to state workshops for the manufacture of secondary products — for example, tallow and leather from cattle; pork from pigs; linen from flax; bread, beer, and basketry from grain.

See Separate Article: TAXES IN ANCIENT EGYPT africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024