Home | Category: Art and Architecture

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN ARCHITECTURE

Seti I Temple at Qurna In ancient Egypt trees were scarce so wood was not widely used as a building material. Mud, clay, rock and reed were the only materials that were in abundance. The ancient Egyptian first lived in reed houses and later switched to unbaked mud brick, which was used even on palaces. Around 2,700 B.C. they developed a method of constructing buildings from stone and within half a century they were building pyramids, and within a century and half they built the Great Pyramid of Cheops.<

"How and why their unexcelled techniques for building in stone were so quickly perfected still puzzles historians," the historian Daniel Boorstin wrote. "How did they quarry huge blocks of limestone, transport them for miles, then raise, place and fit them with jewelers precision? All without the aid of a capstan, a pulley, [beast of burden] or even a wheeled vehicle!" [Source: Daniel Boorstin, "The Creators"]

Large houses, temples and tombs all had similar plans — with a main court, hall and private rooms — that was also found in Greek architecture. The Egyptians and Assyrians used enamel bricks to decorate their buildings. The Greeks and Romans were masters of using enamels to make jewelry.

The materials and stones used to construct new monuments for a Pharaoh were often looted from the temple of another Pharaoh. Sometimes the first thing a god king did when he seized power was erase the names of previous rulers on existing monuments and replace them with his own. Many projects including the sphinx were left unfinished. According to Lehner "New pharaoh, new project. It’s not much different from today." When a pharaoh died before his pyramid was finished it was perhaps considered "a cause of embarrassment or even horror among the populace." [Source: ♣, David Roberts, National Geographic, January 1995]

One reason Egypt was able to build such large temples and pyramids was that it was relatively untroubled by wars and could devote its manpower to construction projects rather than the military. For the most part only temples and tombs have survived because other buildings were built of materials such as wood and mud brick which have dissolved with time.

Websites on Ancient Egypt: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Discovering Egypt discoveringegypt.com; BBC History: Egyptians bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/egyptians ; Ancient History Encyclopedia on Egypt ancient.eu/egypt; Digital Egypt for Universities. Scholarly treatment with broad coverage and cross references (internal and external). Artifacts used extensively to illustrate topics. ucl.ac.uk/museums-static/digitalegypt ; British Museum: Ancient Egypt ancientegypt.co.uk; Egypt’s Golden Empire pbs.org/empires/egypt; Metropolitan Museum of Art www.metmuseum.org ; Oriental Institute Ancient Egypt (Egypt and Sudan) Projects ; Egyptian Antiquities at the Louvre in Paris louvre.fr/en/departments/egyptian-antiquities; KMT: A Modern Journal of Ancient Egypt kmtjournal.com; Egypt Exploration Society ees.ac.uk ; Amarna Project amarnaproject.com; Abzu: Guide to Resources for the Study of the Ancient Near East etana.org; Egyptology Resources fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Encyclopedia of Ancient Egyptian Architecture” by Dieter Arnold (2003) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Construction and Architecture” by Somers Clarke and R. Engelbach (2014) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Architecture in Fifteen Monuments” by Felix Arnold (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Art and Architecture of Ancient Egypt” by W. Stevenson Smith (1999) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Homes” by Brenda Williams, for older kids, (2002) Amazon.com;

“Egyptian Towns and Cities” by Eric Uphill (2008) Amazon.com;

“Building in Egypt” by Dieter Arnold (1991) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Egyptian Masonry: The Building Craft” by Somers Clarke and R. Engelbach | (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Art of Earth Architecture: Past, Present, Future” by Jean Dethier (2020) Amazon.com;

“Architecture, Astronomy and Sacred Landscape in Ancient Egypt” by Giulio Magli (2013) Amazon.com;

“Architecture and Mathematics in Ancient Egypt” by Corinna Rossi (2004) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Architecture: Mesopotamia, Egypt, Crete, Greece”

by Seton Lloyd , Hans Wolfgang Muller, et al. (1974) Amazon.com;

Roots of Ancient Egyptian Architecture

Egyptian architecture most likely had its roots in wood or clay. An indication of this is the practice of "battered walls." This means that they slant upwards from a broad base. These slanting walls are topped by horizontal molding on which leaf and stem patterns are often carved or painted. These patterns are reminders of a time when walls were built of matting stiffened with long reds or tree branches and covered with clay. Such walls can only stand vertically if they are low: higher walls are built at a slant. Walls made of stone don’t need to slant, but the practice of slanting continued after stone came into use.

.jpg)

Edfu Temple

In the remote ages, when Egypt was not so destitute of trees as in historical times, wood was extensively used for building. We have already endeavored to reconstruct an ancient wooden palace. We have also spoken of the old form of door, which, with its boards and laths, we recognise at once as carpenters' work. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

One architectural feature that owes its form to wood — the material in which it was first constructed — is the pillar. The pillar was originally the wooden prop which helped to support the roof, and could not be dispensed with even in a mud building, except in the narrow passage-like rooms usual in Assyrian architecture. Two supplementary features were naturally derived from this pillar: where it stood on the ground, it was necessary to heap up clay to give it a firmer hold, and where the beam of the roof rested on it, the weight was divided by means of a board which was placed between the beam and the pillar. Both these features were retained in the Egyptian column, they constitute the round base and the square abacus. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

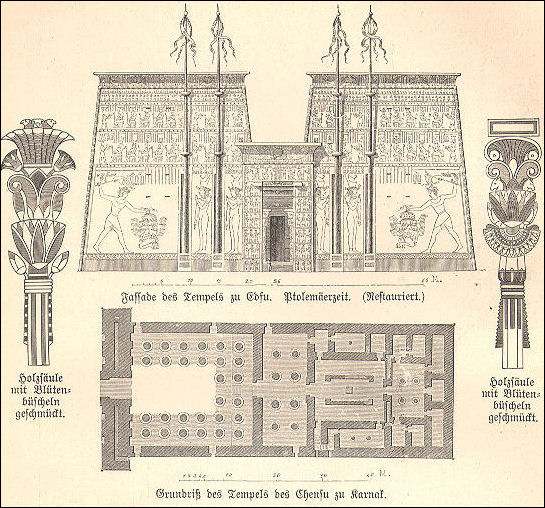

Ancient Egyptian Temple Architecture

Temples from the Middle Kingdom onward were in large rectangular spaces enclosed by high walls with entrances flanked by two large pylons (sloping towers), with a door between them. After passing through the pylons, one entered a large courtyard with colonnades on two or three sides. This is where people gathered. Beyond the courtyard was a large hypostyle hall (a forest of columns that supported a roof). Beyond this a was sanctuary in which a statue of the deity was placed on a boat or in a shrine. Only the pharaoh and high level priests were allowed to enter this area.

Large temples, like the one at Karnak, had a series of courtyards, each with pylons, leading from the entrance, and multiple sanctuaries. These temples were regarded as embodiments of ancient Egyptian cosmology and symbols of renewal, a concept in which Egyptian civilization was largely based. The ceiling of a temple was viewed as the heavens; the floor, the fertile marsh from which life emerged. The pylons at the entrance were shaped like the hieroglyphic for “horizon,” and the whole structure, like the horizon, was seen as the nexus of heaven and earth, divine and mortal, order and chaos. The polarities and contradictiosn of the world remained in harmony and balance as long as certain rites were carried out by the Pharaoh.

Some Egyptian columns were built with ridges to imitate bundled reeds. There were ones with closed papyrus capitals and ones with open papyrus capitals.

One reason Egypt was able to build such large temples and pyramids was that it was relatively untroubled by wars and could devote its manpower to construction projects rather than the military.

Pillars in Ancient Egyptian Architecture

One architectural feature that owes its form to wood — the material in which it was first constructed — is the pillar. The pillar was originally the wooden prop which helped to support the roof, and could not be dispensed with even in a mud building, except in the narrow passage-like rooms usual in Assyrian architecture. Two supplementary features were naturally derived from this pillar: where it stood on the ground, it was necessary to heap up clay to give it a firmer hold, and where the beam of the roof rested on it, the weight was divided by means of a board which was placed between the beam and the pillar. Both these features were retained in the Egyptian column, they constitute the round base and the square abacus. [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

The most simple form of pillar in common use, if we except the plain square pillar, was the so-called proto-doric column, which occurs frequently before the time of and during the 18th dynasty. It is a simple pillar, 8 or 16 sided, with base and abacus, but no capital. The latter was always of secondary importance, and was apparently derived from the ornamentation of the pillars. The decoration of the pillars was connected with the universal love for flowers in Egypt; a special instance of which is seen in the custom of giving the pillars the form either of flowers or of bunches of flowers. Hence there arose in old times two principal types, which we may designate as flower-pillars and bud-pillars. In its oldest form the latter represents four lotus buds, which are bound together so that their stalks form the shaft and their buds the capital; in later times the general scheme of this pretty idea is alone retained, and the detail is often replaced by other favorite ornamentation. The flower-pillar is more difficult to understand, it represents the calyx of a large gay flower placed as a capital on a round shaft; During the New Kingdom this form was often treated very arbitrarily. ' A third form of pillar occurs more rarely, but may be traced back as far as the Middle Kingdom; from later examples we judge that this pillar was intended to represent a palm with its gently-swaying boughs.

A new development of the pillar is found in the so-called Hathor capital, which was certainly in use before the time of the New Kingdom, though, as it happens, we cannot identify it in the scanty materials we possess. The upper part of the pillar is adorned, in very low relief, with a face recognisable by the two cow's cars as that of the I'. gyptian goddess of love, who may have been revered in some Egyptian sanctuary as a pillar carved in this fashion. In the same way in early times the pillar tj, the sacred emblem of Osiris of Dedu, was employed in architecture, and by the combination of this pillar with the round arch, flat mouldings and other ornaments, the Egyptians were able to create very charming walls with carved open work.

Ornamentation in Ancient Egyptian Architecture

Ornamention sin the brick buildings — the gay bands and the surfaces covered with patterns, which were apparently derived in great measure from the custom of covering the walls with gaily-colored mats — were directly assimilated into stone architecture. We cannot emphasise too strongly the fact that the forms of Egyptian architecture, as we know them, were rarely intended originally for the places in which we see them. The dainty bud and flower pillars were not really intended to be constructed with a diameter of four meters (12 feet) and to reach a height of over 19 meters (60 feet). [Source: Adolph Erman, “Life in Ancient Egypt”, 1894]

We cannot here trace the details of the development of the architectural forms in the great temple buildings, though the movement was confined to comparatively narrow limits. These forms however were evidently developed in a freer fashion in the private buildings; unfortunately these are now known to us only by representations in the tombs. For instance, the pillars of the verandahs, shown in representations of the time of the New Kingdom, often exhibit forms of exuberant fantasy. When we see dead geese carved upon the pillars as decoration, as at Tell el Amarna," or when, as in a chapel of the time of the 20th dynasty, three capitals are placed one above the other, and connected together by a support so thin that it appears that the pillar must break, we are convinced that the direction followed in the architecture of private houses was not in any way subservient to the traditional rules observed in the temples. The faint remains of a painting also, which are still to be seen in a window recess in the palace of Medinet Habu (a practised eye will recognise a basket of fruit and flowers), betrays a decorative style unknown in the sanctuaries of the gods. Evidently in architecture, as in painting and sculpture, side by side with the stiff conventional style, a more living art was developed, which shook itself free from the dogmas of tradition; unfortunately it is almost unknown to us, as it was exclusively employed in private buildings which have long since disappeared.

Such is this labyrinth: but a cause for marvel even greater than this is afforded by the lake, which is called the lake of Moiris, along the side of which this labyrinth is built. The measure of its circuit is three thousand six hundred furlongs (being sixty schoines), and this is the same number of furlongs as the extent of Egypt itself along the sea. The lake lies extended lengthwise from North to South, and in depth where it is deepest it is fifty fathoms. That this lake is artificial and formed by digging is self-evident, for about in the middle of the lake stand two pyramids, each rising above the water to a height of fifty fathoms, the part which is built below the water being of just the same height; and upon each is placed a colossal statue of stone sitting upon a chair. Thus the pyramids are a hundred fathoms high; and these hundred fathoms are equal to a furlong of six hundred feet, the fathom being measured as six feet or four cubits, the feet being four palms each, and the cubits six. The water in the lake does not come from the place where it is, for the country there is very deficient in water, but it has been brought thither from the Nile by a canal; and for six months the water flows into the lake, and for six months out into the Nile again; and whenever it flows out, then for the six months it brings into the royal treasury a talent of silver a day from the fish which are caught, and twenty pounds when the water comes in.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum, The Egyptian Museum in Cairo

Text Sources: UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, escholarship.org ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Egypt sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Tour Egypt, Minnesota State University, Mankato, ethanholman.com; Mark Millmore, discoveringegypt.com discoveringegypt.com; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2024

drawing of the Pyramid of Amenemhat III at Hawara and the surrounding ruins, made by Karl Richard Lepsius 1850

Favorite images for ornamentation included papyrus reeds, lotus-buds, water flowers, birds and fishes, marsh scenes and the “bird-tanks of pleasure. " The lovely maiden wading through the rushes to pick the flowers, or catching a duck as she swims through the water; the lion in the reeds robbing the cow of her calf; the tank with its lotus flowers and fish; the merry pictures of the harem on the water with the master, and the rough play with him; the little boxes and bowls in the shape of geese, fish, and flowers — everywhere and continually we have allusions to the pleasures of life to be enjoyed in the marshes.

The industrial arts made good use of architectural forms and ornamentation; boxes finished off at the top with a hollow gorge, and rouge pots in the form of pillars, exist in great numbers. At the same time special forms were developed in this branch of art — forms worthy of more attention than they have received as yet. In part, they owe their individual style to the peculiar properties of the material used, and to the technique; this is the case with the pottery and wood-carving. For instance, the well-known pattern resembling an arrow-head, used for little wooden boxes and other objects, is the natural outcome of the cutting of a piece of wood, and in the same way the so-called panelling in the sides and covers of boxes, which appears as early as the 6th dynasty," represents a peculiarity due to a joiner's mode of working.

In a great measure also imitations from the world of nature were employed for the smaller objects of art; these might either be carved in the form of animals or plants, or representations of both might be used in their ornamentation. It is very interesting to observe what manner of ideas were especially brought into play for this purpose. In the first place, connected with hunting, we find seats supported by lions, and little ointment bowls in the form of gazelles tied up. From the subject of war, we get during the New Kingdom the figures of the captives supporting the flat tops of tables, or carrying little ointment bowls as tribute on their shoulders, or, as in a pretty example in the Giza museum, serving as a pair of scissors. Figures of beautiful girls as well as of pet monkeys occur as a matter of course; the latter may be seen reaching up on one leg to get a look into the rouge pot, or twining themselves round this important toilet requisite.

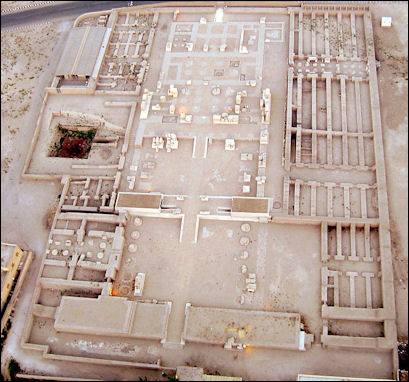

Mortuary of Amenhotep III

Mortuary of Amenhotep III (excavation at the Colossi of Memnon) was once the largest and most impressive temple complex in the world. Known as “The House of Millions of Years,” it embraced gates, colonnades, courts filed with reliefs and inscriptions, and halls with columns more than 15 meters high. In its day it was filled with colorful royal banners hanging from cedar poles on red granite pedestals. Amenhotep III called the complex “a fortress of eternity” and said it was built “out of god white sandstone — worked with gold throughout. Its floors were purified with silver, all of its doorways were of electrum” — an alloy of gold and silver. Over the centuries, though, earthquakes, floods and looting, much of it by 19th century Europeans, have reduced the temple to buried ruins.

Larger than Vatican City and more vast than the massive Karnak and Luxor temples, the Mortuary Temple of Amenhotep III was the length of seven football fields and stretched from the colossi to sacred altars pointing towards the Valley of the Kings. During Amenhotep III’s rule the Nile flowed just a few hundred meters away from the temple. The Colossi of Memnon once stood in front of it. The massive front gate, or pylon, was once brightly painted in blues, red,, greens, yellows and whites.

Merenptah's Mortuary Temple

The Mortuary Temple of Amenhotep III has been excavated since 1999 by a team led by Baghdad-born, Armenian archeologist Hourig Sourouzian. The is some sense of urgency to the project as archeologists are worried about salty runoff and irrigation water groundwater and seepage from the Nile damaging the sculptures that are underground. The restoration plan calls for much of the temples to be reconstructed but that will take many years — even decades — to complete. Just piecing statues and columns back together take a lot of time. Sections are being completed and opened bit by bit.

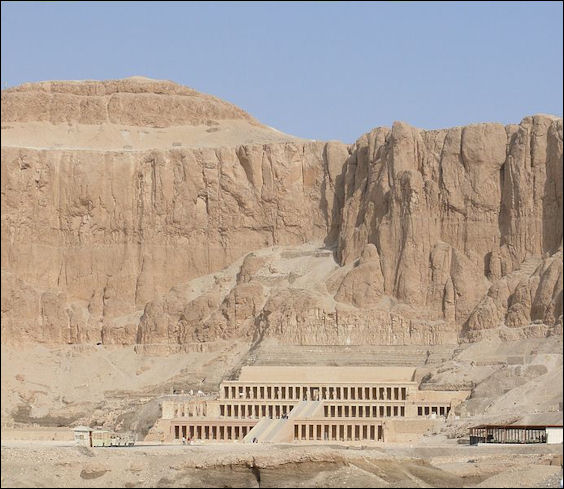

Hatshepsut's Temple

Hatshepsut's Temple (near Valley of the Kings) was built in 1480 B.C. by Queen Hatshepsut, arguably the most powerful female ruler of ancient Egypt. Dedicated to Amun and several other deities and reached by a long ramp, it is comprised of three terraces of colonnades, connected by massive ramps, and a small chamber tunneled deep into the rock. The last set of colonnades is set into the face of a towering red sandstone cliff on the eastern face of a Thebean mountain.

The Temple of Hatshepsut begins with the large first courtyard in front to the temple. A ramp sided by pillars leads to a second courtyard. At the back of this is a colonnade with walls and small enclosures with engravings and reliefs of episodes from the queen’s life and images of gods.

Queen Hatshepsut planted botanical gardens and had incense burned on the terraces. During her funeral she was carried up the ramps to funerary chamber inside the temple. The temple was desecrated and vandalized by her successor. In the 7th century the Copts used the temple as a monastery.

The rear wall of the second courtyard consists of the Birth Colonnade on one side of the ramp and the Punt Colonnade on the other. The Birth Colonnade is a small sheltered area of the terrace that describes the preparation for and birth of Queen Hatshepsut. Particularly interesting is the scene of birds being captured in nets. Many of the victims of the 1997 attack were attacked in this area.

Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut

Luxor Temple

Luxor Temple (across the street from the Nile, next to the town of Luxor) was dedicated to the Amum, the god of fertility and growth, his wife Mut and their son Khonsu. Probably built on the site of an earlier temple, Luxor temple was started and extensively built by 2,623 slaves under Amenhotep III and completed a century later by Ramses II. Other pharaohs, Alexander the Great and the Romans also contributed to the effort. The Arabs even built a mosque inside one of the courtyards.

Luxor Temples is 260 meters long consists of four major structures connected to one another in a long row. They are (beginning at the entrance): 1) the courtyard of Ramses II; 2) the colonnade of Amenhotep III; 3) the courtyard of Amenhotep III; and 4) hypostyle hall and sacarium of Amenhotep III.

In ancient times the entire complex was surrounded by a massive wall. Unlike Greek temples which were meant to be viewed by everyone, Egyptian temples were not supposed to be seen by ordinary people. Every year a sacred procession commemorating the marriage between Amum and Mut moved across the Nile by boat from Karnak to Luxor Temple.

Luxor Temple was restored in the mid 1990s. The $2.2 million job included dismantling 22 columns and installing a system to halt the rise of underground water. Luxor Temple doesn't have a Light and Sound Show but it is open until 10:00pm. It is worth making a visit at night when temperatures are cool and the statues, reliefs and walls are illuminated with floodlights.

Entrance to Luxor Temple

Before the entrance is a long stone “dromos” “a walkway and precession route sided by sphinxes with the face of Ramses II. At one time a dromos and processional avenue connected Luxor with Karnak. There some 1,400 sphinxes spread along the two-mile route..

The façade of the entrance gate consists of a pylon (massive gate), two 15-meter-high granite seated statues of Ramses II, and once had two 25-meter obelisks (only one of which remains, the other was taken to Paris in 1833 and now sits in the Place de Concorde).

Ramses II erected a massive 65-meter-high pylon at the entrance of the temple. The front is decorated with scenes from Ramses II’s military campaigns against the Hittites. At one time four statutes sat in front of the pylon. One representing Queen Nefertari was never finished. A ruined one to the right is of her’s and Ramses’ daughter Merit-Amon.

Luxor Temple

Courtyards at Luxor Temple

The Courtyard of Ramses II (beyond the entrance of Luxor Temple) is surrounded by a double row of thick stubby columns with bud papyrus capitals. On the intercolumns on the south side of the courtyard are Orisis-like statutes of Ramses II. The columns were arranged in two closely-packed concentric squares to hold up the (now missing) heavy roof and to keep the entire temple from collapsing under its own weight.

The courtyard was built as a parallelogram instead of a rectangle so it would be oriented toward the Nile. At the northwest of the courtyard you can see the sacred boats built by Thutmosis II and dedicated to the triad of Amon, Mut and Khonsu. In the southwest corner a relief shows a procession of bulls being led to a sacrifice by bulls. The Colonnade of Amenhotep III (after the courtyard of Ramses II of Luxor Temple) is a 52-meter-long hall with 14 massive pillars, arranged in two parallel rows of seven.

The Courtyard of Amenhotep III (after the courtyard of Colonnade of Amenhotep III) is a second courtyard surrounded on three sides by double rows of columns with closed papyrus capitals. The Sacrarium of Amenhotep III (after the Courtyard of Amenhotep III of Luxor Temple) consists of a hypostyle hall with 32 pillars, a sanctuary for the sacred boat and a kiosk built by Alexander the Great. In the middle of the "maximum security labyrinth" of symmetrically arranged chapels and chambers, is four columned room with a holy shrine, which only the pharaohs and the highest priests were allowed to enter. The climatic rituals of the 15-day Opet festival occurred here. In the rear chambers are a number of engravings of a fertility god with a large erect penis.

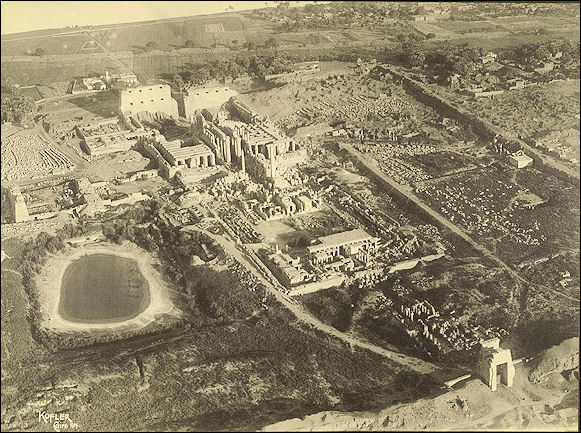

Karnak

Temple of Karnak

The Temple of Karnak (2 miles north of Luxor) ranks with the Pyramids as most amazing site in Egypt and by some estimates is the largest religious structure ever created. Over two millennia it was enlarged and enriched by consecutive pharaohs until it covered 247 acres of land on the Nile’s east bank. At its height it stretched over an area of one mile by a half a mile — about half the size Manhattan — and was like a city, containing its own administrative offices, palaces, treasuries bakeries, breweries, granaries and schools. "Karnak" is the Arabic word for fort. It used to be called Ipetesut—“most esteemed of places.”

There are three main areas at Karnak are: 1) the Sanctuary of Amon; 2) the Sanctuary of Mut, 3) Sanctuary for Montu. Each is separated by a rough brick boundary and each has a main temple in the middle of the enclosure. Next to the main temples were sacred lakes where ceremonies were held. Unlike most other temples in Egypti, Karnak has two axes: one following the sun from east to west; and the other following the Nile from north to south. The largest structure contains the largest columns in the world.

Most of the structures at Karnak are part of the Sanctuary of Amon, which covers an area of about 60 hectares and is dedicated to Amon, the god of fertility and growth. To the south is the Sanctuary of Mut, which covers an area of about 9 hectares and is dedicated to Mut, the wife of Amon. Mut is symbolically portrayed in the form a vulture. To the north is a small Sanctuary for Montu, which covers an area of about 2½ hectares and is dedicated to Montu, the God of War.

See Separate Article: KARNAK TEMPLE: ARCHITECTURE, COMPONENTS, SETTLEMENTS, DECORATIONS AND GREAT HYPOSTYLE HALL africame.factsanddetails.com

ariel view of Karnak

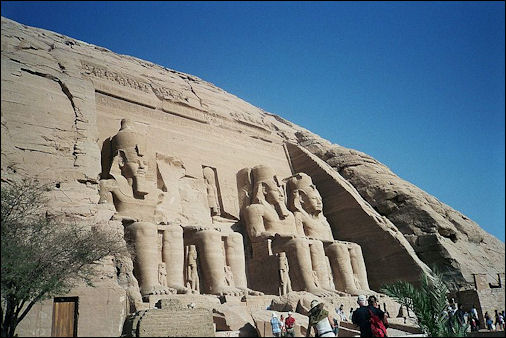

Abu Simbel

Abu Simbel (170 miles south of Aswan) is a monumental temple in southern Egypt with four colossal seated statues — two of Ramses the Great (Ramses II) and two of his wife Neferteri — and two main temples — one dedicated to the sun god Ra-Harakhte, built into the cliff behind the colossal statues, and another dedicated to Hathor built into a cliff on an adjacent hill.

The rock-hewn "grotto" temples at Abu Simbel are somewhat unique. The style is more associated more with the Nubians and other Middle Eastern cultures than with the ancient Egyptians. Unlike many other Pharonic temples, Abu Simbel was never taken over by the Romans or turned into a church by Christians.

Abu Simbel was rediscovered in 1813 by John Lewis Burckhardt. In 1817, after weeks of digging, the Italian adventurer Giovanni Belzoni cleared away enough sand to penetrate the temple. Two years later when the Nefertari’s shrine was uncovered tourists starting venturing down the Nile to visit the site and have been coming every since. The statues are best seen at sunrise.

The Colossal Statues at Abu Simbel are each 67 feet high and weigh 1,200 tons. Each eye is nearly three feet across. The statues were commissioned by Ramses and finished about 1260 B.C., coinciding more or less with Ramses 30 year jubilee when the pharaoh was 45. The statues were chiseled out of the mountainside, and, like the Sphinx and most other Egyptian temples, they were originally painted with bright colors. Scientist have been a able to ascertain from minute paint fragments left behind that the pharaohs headdresses were blue and gold, their skin was pink and the background was painted white.

Abu Simbel Temple

Abu Simbel Temple (behind the statues) is dedicated to the sun god Ra-Harakhte, and the gods Amun, Ptaj and a deified Ramses II. It is inside the cliff behind the statues and is 160 feet deep. Archaeologists have long wondered why Ramses built this temple so far to south of major Egyptian cities. Most believe it was a statement to the Nubians of the power of the pharaoh.

The original temple was built on a site where twice a year — on February 22nd (Ramses II’s birthday) and October 22nd (the anniversary of Ramses II’s coronation) — the morning sun penetrated into the temple's deepest chamber. The timing is probably connected to the symbolic unification, via the rays of the sun, of the statue of Ra-Rorakhty and the statue of Ramses II.

Abu Simbel

High on the facade there is a of carved baboons, smiling at the sunrise. On the door of the temple there is a beautiful inscription of the kings name. Above the door is the falcon-headed deity, Re-Harakhti. Between the legs of the colossal statues on the facade are statues of Ramses family, his mother "Mut-tuy," his wife "Nefertari" and his sons and daughters.

The temple itself was made up of chambers, storerooms, square painted pillars and two halls with yet more statues of Ramses and a few of the gods. Specialist who worked at the City of the Dead completed most of the subterranean temple with bronze tools.

There are also a number of dedications. Important among these is one of Ramses II's marriage to the daughter of a Hittite king. Beyond the entrance is the Great Hall of Pillars, with eight 32-foot-high pillars of Ramses defied as the God Osiris. The walls have inscriptions recording the Battle of Kadesh against the Hittites. The smaller Hall of Nobles contains four square pillars. The sacred central sanctuary contains a shrine pierced by the sun on Ramses’s birthday, February 21, and his coronation day, October 22.

Temple of Nefertari and Hathor at Abu Simbel (on a hill adjacent to the hill with the colossal statues and the main temple) is a smaller temple fronted by more Ramses stature with two statues of Nefertari, sandwiched in between. Dedicated to Hathor, the goddess of Love and Beauty, and Nefertari, the temple is chiseled into the cliff behind the statues and is thought to have been completed before the Ramses temple. The two temples have similar designs.

The four facade statues of Ramses and two of Nefertari are 33 feet tall. The statues of the queen are smiling. The upper portion of the second statue on the Ramses temple is believed to have fallen off during the Pharaoh's time from stresses in the rock. Queen Nefertari is portrayed with cows horns of the goddess Hathor. The entrance of the Temple of Hathor leads to a hall containing six pillars bearing the head of the goddess Hathor. The eastern wall bears inscriptions depicting Ramses striking some enemies before the gods Ra and Amum. Other wall scenes show Ramses and Nefertari offering sacrifices to the gods and performing religious rituals. There are also superb reliefs of the Battle of Kadesh. Beyond this is another wall with similar scenes and paintings. In the sacred central shrine there is a statue of Hathor.

Ptolemaic-Egyptian Temples

Dendara (near Cairo) is the home of the Temple of Hathor, dedicated to the cow-headed goddess of healing. One of the best preserved temples in Egypt, it was built in the first century B.C. by the Ptolemaic Greeks and is famous for a ceiling painting, with astronomical symbols, and its great Hypostyle Hall. It even has a roof. The temple incorporates both Greek and Egyptian architectural styles. The 24 massive papyrus pillars in the main hall are capped with images of Hathor and decorated with hieroglyphics and Egyptian symbols. The stone ceiling features an Egyptian version of the star-lit sky, with goddess Nut, who, Egyptians believed, spanned the sky with her body and swallowed the sun each night and gave birth to it each morning. One of one of the walls is a famous picture of Cleopatra and Caesarian, her son from Julius Caesar.

Edfu (80 miles north of Aswan) is the home of the Temple of Horus, a huge and exquisite Ptolemaic Greek temple built to honor the falcon-headed son of Orisis. Regarded as the largest best-preserved ancient temples in Egypt, it took over 200 years to build and was finally finished by Cleopatra’s father. Rediscovered in 1869, it features wonderful reliefs of Ptolemy XIII pulling the hair of his enemies like a pharaoh; depictions of the Feats of the Beautiful Meeting, the annual reunion between Horus and his wife Hathor; and a particularly fine ceiling relief of the goddess Nut in the New Year Chapel. There is also a Nilometer, a Court of Offerings and a huge pylon (massive gate) at the entrance. In the 19th century , Flaubert wrote it “served as the public latrine for the entire” town. Flaubert liked the town’s dancers who did a kind of striptease called the bee.”

Kom-Ombo (30 miles north of Aswan) is the home the unique Temple of Sobek and Horus, a Ptolemaic Greek temple dedicated to a local crocodile god (Sobek) and a local sky god (Horus). Located in a spectacular setting, a dune overlooking the Nile and surrounded by sugar cane fields, the temple was built in a mirror-like fashion — one side dedicated to Horus, the other to Sobek — so neither god would be offended. The are two courts, two colonnades, and two sanctuaries.

The Temple of Sobek and Horus is famous for its halls and entrances. Sculpted wall reliefs include one showing ancient surgical instruments, bone saws and dental tools. Worth checking out are the hieroglyphic-inscribed pillars. A number of crocodiles mummies have been found in the area of the Chapel of Harthor. There are some Old Kingdom tombs near Kom-Ombo village.

Temple of Philae (on Agilika Island between Aswan Dam and Aswan High Dam) is dedicated to Isis, who is said to have found the heart of her slain brother Osiris on Philae Island. Most of the existing structures were built by the Ptolemies and Romans. Christians used the hypostyle hall as a church. The ruins consist of two major Ptolemaic and Roman temples: the monolithic Kiosk of the Emperor Trajan; and the Temple of Isis with its lovely colonnades. "In all Nubia there is no more harmonics combination or architecture and scenery," says Arab expert George Gerster. There is also a temple dedicated to Hathor, a Birth House and two pylons (massive gates). The island has a light and sound show. Some of the ancient reliefs on the temples were chiseled off by Christians.

Edfu

Labyrinth of the City of Crocodiles

The Labyrinth of Egypt was the name given to a complex labyrinthine structure that once stood near the foot of the Pyramid of Amenemhat III at Hawara. It was built by Amenemhat III, who ruled c. 1800 BC as the sixth pharaoh of the Twelfth Dynasty. Karl Richard Lepsius also discovered cartouches bearing the name of Amenemhat's daughter, Sobekneferu, suggesting that she made additions to the complex's decorations during her reign as king of Egypt. The structure may have been a collection of funerary temples such as the ones that are commonly found near Egyptian pyramids. Since the temple was destroyed in antiquity, it can only be partially reconstructed. A north-south oriented perimeter wall enclosed the entire complex which thus measured 385 meters (1,263 feet) by 158 meters (518 feet), and the floorplan of the Labyrinth itself is estimated to have covered around 28,000 square meters (300,000 square feet). After excavating the site in 1888, Flinders Petrie argued that the northernmost portion of the Labyrinth had been composed of nine shrines that collectively stood behind twenty-seven columns that ran east-to-west; in front of these stood twelve columned courts that were divided into two groups by a long hall. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A.D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

Fifth Century B.C. Greek historian Herodotus wrote in Book 2 of “Histories”: They caused to be made a labyrinth, situated a little above the lake of Moiris and nearly opposite to that which is called the City of Crocodiles. This I saw myself, and I found it greater than words can say. For if one should put together and reckon up all the buildings and all the great works produced by Greeks, they would prove to be inferior in labor and expense to this labyrinth, though it is true that both the temple at Ephesos and that at Samos are works worthy of note.

The pyramids also were greater than words can say, and each one of them is equal to many works of the Greeks, great as they may be; but the labyrinth surpasses even the pyramids. It has twelve courts covered in, with gates facing one another, six upon the North side and six upon the South, joining on one to another, and the same wall surrounds them all outside; and there are in it two kinds of chambers, the one kind below the ground and the other above upon these, three thousand in number, of each kind fifteen hundred. The upper set of chambers we ourselves saw, going through them, and we tell of them having looked upon them with our own eyes; but the chambers under ground we heard about only; for the Egyptians who had charge of them were not willing on any account to show them, saying that here were the sepulchres of the kings who had first built this labyrinth and of the sacred crocodiles. [Source: Herodotus, “The Histories”, Egypt after the Persian Invasion, Book 2, English translation by A.D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920, Tufts]

Accordingly we speak of the chambers below by what we received from hearsay, while those above we saw ourselves and found them to be works of more than human greatness. For the passages through the chambers, and the goings this way and that way through the courts, which were admirably adorned, afforded endless matter for marvel, as we went through from a court to the chambers beyond it, and from the chambers to colonnades, and from the colonnades to other rooms, and then from the chambers again to other courts. Over the whole of these is a roof made of stone like the walls; and the walls are covered with figures carved upon them, each court being surrounded with pillars of white stone fitted together most perfectly; and at the end of the labyrinth, by the corner of it, there is a pyramid of forty fathoms, upon which large figures are carved, and to this there is a way made under ground.